Abstract

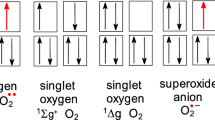

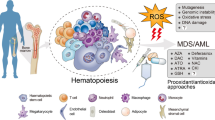

Several agents used for treatment of colon and other cancers induce reactive oxygen species (ROS), and this plays an important role in their anticancer activities. In addition to the well-known proapoptotic effects of ROS inducers, these compounds also decrease expression of specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors Sp1, Sp3, and Sp4 and several prooncogenic Sp-regulated genes important for cancer cell proliferation, survival, and metastasis. The mechanism of these responses involves ROS-dependent downregulation of miR-27a or miR-20a (and paralogs) and induction of two Sp repressors, ZBTB10 and ZBTB4, respectively. This pathway significantly contributes to the anticancer activity of ROS inducers and should be considered in the development of drug combinations for cancer chemotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Ferlay J, Shin H, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM. GLOBOCAN 2008 v1.2, Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide. 2010. Available from http://globocan.iarc.fr. Accessed 17 Jul 2012.

Boyle P, Levin B, editors. World cancer report 2008. Lyon: IARC; 2008. p. 15.

Jemal A et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(2):69–90.

Curado MP, Edwards B, Shin HR. Cancer incidence in five continents. Vol. IX. Lyon: IARC; 2007.

Parkin DM et al. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108.

Chan AT, Giovannucci EL. Primary prevention of colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(6):2029–2043.

Center MM, Jemal A, Ward E. International trends in colorectal cancer incidence rates. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1688–94.

La Vecchia C et al. Dietary total antioxidant capacity and colorectal cancer: a large case–control study in Italy. Int J Cancer. 2013;27(10):28133.

Bird CL et al. Plasma ferritin, iron intake, and the risk of colorectal polyps. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144(1):34–41.

Stevens RG et al. Body iron stores and the risk of cancer. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(16):1047–52.

• Dickinson BC, Chang CJ. Chemistry and biology of reactive oxygen species in signaling or stress responses. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(8):504–11. This review outlines the diverse roles (physiological and pathological) that ROS play in various tissue and organ systems.

Hancock JT, Desikan R, Neill SJ. Role of reactive oxygen species in cell signalling pathways. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29(Pt 2):345–50.

Afanas'ev I. Reactive oxygen species signaling in cancer: comparison with aging. Aging Dis. 2011;2(3):219–30.

Kumar B et al. Oxidative stress is inherent in prostate cancer cells and is required for aggressive phenotype. Cancer Res. 2008;68(6):1777–85.

Vaquero EC et al. Reactive oxygen species produced by NAD(P)H oxidase inhibit apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(33):34643–54.

Waris G, Ahsan H. Reactive oxygen species: role in the development of cancer and various chronic conditions. J Carcinog. 2006;5:14.

Gupta SC et al. Upsides and downsides of reactive oxygen species for cancer: the roles of reactive oxygen species in tumorigenesis, prevention, and therapy. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2012;16(11):1295–322.

Martindale JL, Holbrook NJ. Cellular response to oxidative stress: signaling for suicide and survival. J Cell Physiol. 2002;192(1):1–15.

Medan D et al. Regulation of Fas (CD95)-induced apoptotic and necrotic cell death by reactive oxygen species in macrophages. J Cell Physiol. 2005;203(1):78–84.

Shrivastava A et al. Cannabidiol induces programmed cell death in breast cancer cells by coordinating the cross-talk between apoptosis and autophagy. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(7):1161–72.

Coriat R et al. The organotelluride catalyst LAB027 prevents colon cancer growth in the mice. Cell Death Dis. 2011;2:e191.

Donadelli M et al. Gemcitabine/cannabinoid combination triggers autophagy in pancreatic cancer cells through a ROS-mediated mechanism. Cell Death Dis. 2011;28(2):36.

Chen Y et al. Oxidative stress induces autophagic cell death independent of apoptosis in transformed and cancer cells. Cell Death Differ. 2008;15(1):171–82.

Li J et al. Tephrosin-induced autophagic cell death in A549 non-small cell lung cancer cells. J Asian Nat Prod Res. 2010;12(11):992–1000.

Garbarino JA et al. Demalonyl thyrsiflorin A, a semisynthetic labdane-derived diterpenoid, induces apoptosis and necrosis in human epithelial cancer cells. Chem Biol Interact. 2007;169(3):198–206.

Kim JS et al. Role of reactive oxygen species-mediated mitochondrial dysregulation in 3-bromopyruvate induced cell death in hepatoma cells: ROS-mediated cell death by 3-BrPA. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 2008;40(6):607–18.

Nair RR et al. HYD1-induced increase in reactive oxygen species leads to autophagy and necrotic cell death in multiple myeloma cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8(8):2441–51.

Naito M et al. Caspase-independent necrotic cell death induced by a radiosensitizer, 8-nitrocaffeine. Cancer Sci. 2004;95(4):361–6.

Yogosawa S et al. Dehydrozingerone, a structural analogue of curcumin, induces cell-cycle arrest at the G2/M phase and accumulates intracellular ROS in HT-29 human colon cancer cells. J Nat Prod. 2012;75(12):2088–93.

Noratto GD et al. The drug resistance suppression induced by curcuminoids in colon cancer SW-480 cells is mediated by reactive oxygen species-induced disruption of the microRNA-27a-ZBTB10-Sp axis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2013;8(10):201200609.

Shehzad A et al. Curcumin induces apoptosis in human colorectal carcinoma (HCT-15) cells by regulating expression of Prp4 and p53. Mol Cells. 2013;16:16.

Dinicola S et al. Grape seed extract triggers apoptosis in Caco-2 human colon cancer cells through reactive oxygen species and calcium increase: extracellular signal-regulated kinase involvement. Br J Nutr. 2013;25:1–13.

Papi A et al. Vitexin-2-O-xyloside, raphasatin and (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate synergistically affect cell growth and apoptosis of colon cancer cells. Food Chem. 2013;138(2–3):1521–30.

Yang F et al. Hirsutanol A, a novel sesquiterpene compound from fungus Chondrostereum sp., induces apoptosis and inhibits tumor growth through mitochondrial-independent ROS production: hirsutanol A inhibits tumor growth through ROS production. J Transl Med. 2013;11(32):1479–5876.

Pierre AS et al. Trans-10, cis-12 conjugated linoleic acid induced cell death in human colon cancer cells through reactive oxygen species-mediated ER stress. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;4:759–68.

Thomasz L et al. 6 iodo-delta-lactone: a derivative of arachidonic acid with antitumor effects in HT-29 colon cancer cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fat Acids. 2013;88(4):273–80.

Maillet A et al. A novel osmium-based compound targets the mitochondria and triggers ROS-dependent apoptosis in colon carcinoma. Cell Death Dis. 2013;6(4):185.

Lupidi G et al. Synthesis, properties, and antitumor effects of a new mixed phosphine gold(I) compound in human colon cancer cells. J Inorg Biochem. 2013;124:78–87.

Sun L et al. Reactive oxygen species mediate Cr(VI)-induced S phase arrest through p53 in human colon cancer cells. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 2012;31(2):95–107.

Chintharlapalli S et al. Betulinic acid inhibits colon cancer cell and tumor growth and induces proteasome-dependent and -independent downregulation of specificity proteins (Sp) transcription factors. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:371.

• Gandhy SU et al. Curcumin and synthetic analogs induce reactive oxygen species and decreases specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors by targeting microRNAs. BMC Cancer. 2012;12(564):1471–2407. The authors demonstrate the role of the zinc finger ZBTB4 and microRNAs from miR-17-92 clusters in Sp transcription factor regulation in colon cancer and show a novel mechanism by which curcumin and its structural analogs downregulate Sp proteins through induction of ROS and disruption the miR-20a–miR-17-5-p–ZBTB4 axis.

• Pathi SS et al. GT-094, a NO-NSAID, inhibits colon cancer cell growth by activation of a reactive oxygen species-microRNA-27a: ZBTB10-specificity protein pathway. Mol Cancer Res. 2011;9(2):195–202. This study for the first time shows drug-mediated ROS-dependent disruption of the miR27a–ZBTB10 axis in colon cancer cells leading to downregulation of Sp transcription factors that are involved in cancer cell growth, survival, and metastasis.

Pathi SS et al. Pharmacologic doses of ascorbic acid repress specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors and Sp-regulated genes in colon cancer cells. Nutr Cancer. 2011;63(7):1133–42.

Suske G. The Sp-family of transcription factors. Gene. 1999;238(2):291–300.

Gidoni D et al. Bidirectional SV40 transcription mediated by tandem Sp1 binding interactions. Science. 1985;230(4725):511–7.

Giglioni B et al. The same nuclear proteins bind the proximal CACCC box of the human β-globin promoter and a similar sequence in the enhancer. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;164(1):149–55.

Imataka H et al. Two regulatory proteins that bind to the basic transcription element (BTE), a GC box sequence in the promoter region of the rat P-4501A1 gene. EMBO J. 1992;11(10):3663–71.

Abdelrahim M, Safe S. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors decrease vascular endothelial growth factor expression in colon cancer cells by enhanced degradation of Sp1 and Sp4 proteins. Mol Pharmacol. 2005;68(2):317–29.

Abdelrahim M et al. Tolfenamic acid and pancreatic cancer growth, angiogenesis, and Sp protein degradation. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(12):855–68.

Chintharlapalli S et al. Betulinic acid inhibits prostate cancer growth through inhibition of specificity protein transcription factors. Cancer Res. 2007;67(6):2816–23.

Chadalapaka G et al. Curcumin decreases specificity protein expression in bladder cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68(13):5345–54.

Mertens-Talcott SU et al. The oncogenic microRNA-27a targets genes that regulate specificity protein transcription factors and the G2-M checkpoint in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(22):11001–11.

Safe S, Abdelrahim M. Sp transcription factor family and its role in cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2005;41(16):2438–48.

Abdelrahim M et al. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-1 expression by specificity proteins 1, 3, and 4 in pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67(7):3286–94.

Higgins KJ et al. Regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 expression in pancreatic cancer cells by Sp proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;345(1):292–301.

Abdelrahim M et al. Role of Sp proteins in regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor expression and proliferation of pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2004;64(18):6740–9.

Bouwman P, Philipsen S. Regulation of the activity of Sp1-related transcription factors. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002;195(1–2):27–38.

Black AR, Black JD, Azizkhan-Clifford J. Sp1 and krüppel-like factor family of transcription factors in cell growth regulation and cancer. J Cell Physiol. 2001;188(2):143–60.

Ammendola R et al. Sp1 DNA binding efficiency is highly reduced in nuclear extracts from aged rat tissues. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(25):17944–8.

Adrian GS et al. YY1 and Sp1 transcription factors bind the human transferrin gene in an age-related manner. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1996;51(1):B66–75.

Oh JE, Han JA, Hwang ES. Downregulation of transcription factor, Sp1, during cellular senescence. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353(1):86–91.

• Jutooru I et al. Arsenic trioxide downregulates specificity protein (Sp) transcription factors and inhibits bladder cancer cell and tumor growth. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316(13):2174–88. This study establishes the role of ROS in downregulation of Sp transcription factors and Sp-regulated genes important in cancer cell proliferation, growth, and survival in bladder cancer and several other cancer cell types.

Tillotson LG. RIN ZF, a novel zinc finger gene, encodes proteins that bind to the CACC element of the gastrin promoter. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(12):8123–8.

Scott GK et al. Rapid alteration of microRNA levels by histone deacetylase inhibition. Cancer Res. 2006;66(3):1277–81.

Weber A et al. Zbtb4 represses transcription of P21CIP1 and controls the cellular response to p53 activation. EMBO J. 2008;27(11):1563–74.

•• Kim K et al. Identification of oncogenic microRNA-17-92/ZBTB4/specificity protein axis in breast cancer. Oncogene. 2012;31(8):1034–44. The authors demonstrate a novel mechanism of Sp regulation by microRNAs derived from the miR-17-92 cluster, which suppresses the expression of an Sp repressor, ZBTB4.

•• O'Hagan HM et al. Oxidative damage targets complexes containing DNA methyltransferases, SIRT1, and polycomb members to promoter CpG islands. Cancer Cell. 2011;20(5):606–19. The authors demonstrate that oxidative damage can cause recruiting of silencing complexes containing DNA methyltransferases from the non-GC-rich or transcriptionally poor regions of the genome to GC-rich regions of the genome, which explains global hypomethylation that is commonly observed in cancer.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Sandeep Sreevalsan and Stephen Safe declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sreevalsan, S., Safe, S. Reactive Oxygen Species and Colorectal Cancer. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep 9, 350–357 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11888-013-0190-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11888-013-0190-5