Abstract

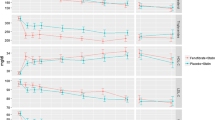

Combination fibrate-statin therapy favorably modifies the atherogenic, triglyceride-rich lipoprotein environment, common to insulin resistance, diabetes, and higher cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk. Five major fibrate randomized clinical trial (RCT) results (HHS, VA-HIT, BIP, FIELD, and ACCORD-Lipid) demonstrated four consistent features: 1) the highest CVD event rates occurred in the placebo subgroups possessing atherogenic “moderate” dyslipidemia (triglycerides, > 200 mg/dL, and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C], < 35–40 mg/dL); 2) with this subgroup having the greatest “hypothesis-generating” fibrate benefit (27% to 65% relative risk reduction, variable significance [P values ranging 0.057–0.005]); 3) those subgroups without moderate dyslipidemia had relatively lower CVD event rates; and 4) little or no benefit from fibrates. The ACCORD-Lipid results, specifically, demonstrated benefits against the background of statin therapy. Three independent meta-analyses combining the five RCTs, which provided a large sample of moderate dyslipidemia participants (i.e., 2401 on fibrates; 2270 on placebo), demonstrated a fibrate benefit with significant heterogeneity of effect across lipid subgroups (P = 0.0002). The fibrate benefit was observed in “low HDL-C only” patients, reducing CVD events by 17% (P < 0.001) or “hypertriglyceridemia-only” patients, reducing CVD events by 28% (P < 0.001), or “atherogenic (moderate) dyslipidemia” phenotype, reducing CVD events by 30% (P < 0.0001), compared with a nonsignificant 6% reduction (P = 0.13) in nonatherogenic dyslipidemia patients. Fibrate RCTs in patients with diabetes (FIELD and ACCORD-Lipid) also demonstrated significant microvascular (ie, retinopathy and nephropathy) outcome benefit possibly independent of lipid levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Abbreviations

- A to Z:

-

Aggrastat-to-Zocor Trial

- ACCORD-Lipid:

-

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes

- BECAIT:

-

Bezafibrate Coronary Atherosclerosis Intervention Trial

- BIP:

-

Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention

- CTT:

-

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists

- DAIS:

-

Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study

- FIELD:

-

Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes

- FIELD CIMT:

-

Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes-Carotid Intima-Media Thickness

- HHS:

-

Helsinki Heart Study

- IDEAL:

-

Incremental Decrease in End Points Through Aggressive Lipid Lowering

- NCEP-ATP:

-

National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III

- PROVE-IT-TIMI 22:

-

Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy-Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 22

- SAFARI:

-

Effectiveness and Tolerability of Simvastatin Plus Fenofibrate for Combined Hyperlipidemia

- SENDCAP:

-

St. Mary’s, Ealing, Northwick Park Diabetes Cardiovascular Prevention

- TNT:

-

Treating to New Targets

- VA-HIT:

-

Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Intervention Trial

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance, •• Of major importance

Austin MA, Breslow JL, Hennekens, et al. Low density lipoprotein subclass patterns and risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1988;260:1917–21.

Reaven G. Banting lecture 1988: role of insulin resistance in human disease. Diabetes. 1988;37(12):1595–607.

Lemieux I, Pascot A, Couillard C, et al. Hypertriglyceridemic waist: a marker of the atherogenic metabolic triad (hyperinsulinemia; hyperapolipoprotein B; small, dense LDL) in men? Circulation. 2000;102:179–84.

Kastelein JJP, Van der Steeg WA, Holme I, et al. Lipids, apolipoproteins, and their ratios in relation to cardiovascular events with statin treatment. Circulation. 2008;117(23):3002–9.

Ginsberg HN. Review: efficacy and mechanisms of action of statins in the treatment of diabetic dyslipidemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(2):383–92.

Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomized trials. Lancet. 2010;376:1670–81.

Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Collins R, Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators, et al. Efficacy of cholesterol-lowering therapy in 18,686 people with diabetes in 14 randomized trials of statins: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371:117–25.

Preiss D, Seshasai SR, Welsh P, et al. Risk of incident diabetes with intensive-dose compared with moderate-dose statin therapy. JAMA. 2011;305:2556–64.

Smith SC, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update a guideline from the American heart association and American college of cardiology foundation. Circulation. 2011;124:000–0.

•• Chapman MJ, Ginsberg HN, Amarenco P et al. for the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol in patients at high risk of cardiovascular disease: evidence and guidance for management. European Heart Journal 2011;32(11):1345–1361. This article reviews the epidemiology linking the TG-rich environment with cardiovascular pathophysiology and recommended lifestyle and pharmacologic treatment modalities.

Cannon CP, Steinberg BA, Murphy SA, et al. Meta-analysis of cardiovascular outcomes trials comparing intensive versus moderate statin therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;48:438–45.

Bruckert E, Hayem G, Dejager S, Yau C, Begaud B. Mild to moderate muscular symptoms with high-dosage statin therapy in hyperlipidemic patients: the PRIMO Study. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2005;19:403–14.

Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375(9716):735–42.

Barter P, Gotto AM, LaRosa JC, et al. for Treating to New Targets Investigators. HDL Cholesterol, Very Low Levels of LDL Cholesterol, and Cardiovascular Events NEJM 2007; 357;13 1301–1310

Miller M, Cannon CP, Murphy SA, et al. Impact of triglyceride levels beyond low-density lipoprotein cholesterol after acute coronary syndrome in the PROVE IT-TIMI 22 trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;51:724–30.

Faergeman O, Holme I, Fayyad R, on Behalf of the Steering Committees of the IDEAL and TNT Trials, et al. Plasma triglycerides and cardiovascular events in the treating to new targets and incremental decrease in end-points through aggressive lipid lowering trials of statins in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2009;104:459–63.

Executive Summary of the Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel On detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). JAMA. 2001; 285: 2486–2497. NIH Publication No. 01–3670. Detailed guidelines on the treatment of hypertriglyceridemia can be found in the Full Report at the NCEP website: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/cholesterol/atp3full.pdf

Jeppeson J, Hein HO, Suadicini P, et al. Low triglycerides–high high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and risk of ischemic heart disease. Arch Int Med. 2001;161:361–6.

Goldenberg I, Benderly M, Goldbourt U. Update on the use of fibrates: focus on bezafibrate. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4(1):131–41.

Fruchart JC, Brewer Jr HB, Leitersdorf E, Members of the Fibrate Consensus Group, et al. Consensus for the use of fibrates in the treatment of dyslipoproteinemia and coronary heart disease: fibrate Consensus Group. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:912–7.

Schoonjans K, Staels B, Auerx J, et al. Role of the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor (PPAR) in mediating the effects of fibrates and fatty acids on gene expression. J Lipid Res. 1996;37(5):907–25.

Landschulz KT, Pathak RK, Rigotti A, Krieger M, Hobbs HH. Regulation of scavenger receptor, class B, type I, a high density lipoprotein receptor, in liver and steroidogenic tissues of the rat. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:984–95.

Ji Y, Jian B, Wang N, Sun Y, de la Llera Moya M, Philips MC, Rothblat GH, Swaney JB, Tall AR. Scavenger receptor BI promotes high density lipoprotein-mediated cellular cholesterol efflux. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20982–5.

Acton S, Rigotti A, Landschulz KT, Xu S, Hobbs HH, Krieger M. Identification of scavenger receptor SR-BI as a high density lipoprotein receptor. Science. 1996;271:518–20.

Farnier M, Bonnefous F, Debbas N, Irvine A. Comparative efficacy and safety of micronized fenofibrate and simvastatin in patients with primary type IIa or IIb hyperlipidemia. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:441–9.

Wang N, Arai T, Ji Y, Rinninger F, Tall AR. Liver-specific overexpression of scavenger receptor BI decreases levels of very low density lipoprotein apoB, low density lipoprotein apoB, and high density lipoprotein in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(49):32920–6.

Kozarsky K, Donahee MH, Rigotti A, Iqbal SN, Edelman ER, Krieger M. Overexpression of the HDL receptor SR-BI alters plasma HDL and bile cholesterol levels. Nature. 1997;387:414–7.

van der Hoogt CC, Westerterp M. Fenofibrate increases HDL-cholesterol by reducing cholesteryl ester transfer protein expression. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:1763–71.

Cromwell WC. High-density lipoprotein associations with coronary heart disease: does measurement of cholesterol content give the best result? J Clin Lipidol. 2007;1:57–64.

Otvos JD. The surprising AIM-HIGH results are not surprising when viewed through a particle lens. J Clin Lipidol. 2011;5:368–70.

Staels B, Koenig W, Habib A, et al. Activation of human aortic smooth-muscle cells is inhibited by PPARα but not by PPARγ activators. Nature. 1998;393(6687):790–3.

Davignon J, Dubuc G. Statins and ezetimibe modulate plasma proprotein convertase subtilisin Kexin-9 (PCSK9) Levels. Trans Am Clin Climatol Assoc. 2009;120:163–73.

Mayne J, Dewpura T, Raymond A, et al. Plasma PCSK9 levels are significantly modified by statins and fibrates in humans. Lipids Health Dis. 2008;7:1–9.

Kourimate S, Le May C, Langhi C, et al. Dual mechanisms for the fibrate mediated repression of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:9666–73.

Lambert G, Ancellin N, Charlton F, et al. Plasma PCSK9 concentrations correlate with LDL and total cholesterol in diabetic patients and are decreased by fenofibrate treatment. Clin Chem. 2008;54:1038–45.

Konrad RJ, Troutt JS, Cao G. Effects of currently prescribed LDL-C-lowering drugs on PCSK9 and implications for the next generation of LDL-C-lowering agents. Lipids Health Dis. 2011;10:38.

Baass A, Dubuc G, Tremblay M, et al. Plasma PCSK9 is associated with age, sex, and multiple metabolic markers in a population-based sample of children and adolescents. Clin Chem. 2009;55(9):1637–45.

Grundy SM, Vega GL, Yuan Z, et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of simvastatin plus fenofibrate for combined hyperlipidemia (the SAFARI trial). Am J Card. 2005;95(4):462–8.

Saha SA, Kizhakepunnur LG, Bahekar A, et al. The role of fibrates in the prevention of cardiovascular disease – a pooled meta-analysis of long-term randomized placebo-controlled clinical trials. Am Heart J. 2007;154:943–53.

•• Ginsberg HN, Elam MB, Lovato LC, et al. for The ACCORD Study Group, Effects of Combination Lipid Therapy in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. NEJM 2010 362(17):1563–1574. The article describes the ACCORD-Lipid study trial results including the prespecified analysis demonstrating the high-risk atherogenic moderate dyslipidemia subgroup and the increased effectiveness of fenofibrate in reducing cardiovascular events, relative to other subgroups.

Frick MH, Elo O, Haapa K, NEJM, Helsinki Heart Study: Primary Prevention Trial with Gemfibrozil in Middle-aged Men with Dyslipidemia NEJM 1987 317(20):1237–1245

Manninen V, Tenkanen L, Koskinen P, et al. Joint effects of serum triglyceride and LDL cholesterol and HDL cholesterol concentrations on coronary heart disease risk in the Helsinki Heart Study. Implications for treatment. Circulation. 1992;85:37–45.

Brunner D, Agmon J, Kaplinsky E, for The BIP Study Group. Secondary prevention by raising HDL cholesterol and reducing triglycerides in patients with coronary artery disease: the Bezafibrate Infarction Prevention (BIP) study. Circulation. 2000;102:21–7.

Robins SJ, Collins D, Wittes JT, et al. Relation of gemfibrozil treatment and lipid levels with major coronary events: VA-HIT: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:1585–91.

Robins SJ, Rubins HB, Faas FH, et al. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular events with low HDL cholesterol the Veterans Affairs HDL Intervention Trial (VA-HIT). Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1513–7.

Otvos JD, Collins D, Freedman DS. Low-density lipoprotein and high-density lipoprotein particle subclasses predict coronary events and are favorably changed by gemfibrozil therapy in the veterans affairs high-density lipoprotein intervention trial. Circulation. 2006;113:1556–63.

Keech A, Simes RJ, Barter P, for The FIELD study investigators, et al. Effects of long-term fenofibrate therapy on cardiovascular events in 9795 people with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the FIELD study): randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366:1849–61.

Scott R, O’Brien R, Fulcher G, et al. Effects of fenofibrate treatment on cardiovascular disease risk in 9,795 individuals with type 2 diabetes and various components of the metabolic syndrome: the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) study. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:493–8.

Tenkanen L, Manttari M, Kovanen PT, et al. Gemfibrozil in the treatment of dyslipidemia. An 18-year mortality follow-up of the Helsinki Heart Study. Intern Med. 2006;166:743–8.

Tenenbaum A, Motro M, Fisman EZ. Bezafibrate for the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction in patients with metabolic syndrome. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1154–60.

Goldenberg I, Boyko V, Tennenbaum A, et al. Long-term benefit of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol–raising therapy with bezafibrate 16-year mortality follow-up of the bezafibrate infarction prevention trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):508–14.

Elkeles RS, Diamond JR, Poulter C, et al. Cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a double-blind placebo-controlled study of bezafibrate: the St. Mary’s Ealing, Northwick Park Diabetes Cardiovascular Disease Prevention (SENDCAP) Study. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:641–8.

Ericsson C-G, Hamsten A, Nilsson J, et al. Angiographic assessment of effects of bezafibrate on progression of coronary artery disease in young male postinfarction patients. Lancet. 1996;347:849–53.

Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study Investigators. Effect of fenofibrate on progression of coronary artery disease in type 2 diabetes: the diabetes atherosclerosis intervention study, a randomized study. Lancet. 2001;357:905–10.

• Jun M, Foote C, Lv J, et al. Effects of fibrates on cardiovascular outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2010; 375:1875–1884. A meta-analysis of entire cohorts of 18 fibrate trials demonstrating benefits limited to nonfatal MI.

•• Sacks FM, Carey VJ, Fruchart JC. Combination lipid therapy in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:692–694. This article is one of three independent meta-analyses powering the atherogenic moderate dyslipidemia cohorts from the five major fibrate trials, demonstrating the highly significant 26% to 35% RRR (P < 0.0001) of CVD events.

•• Bruckert E, Labreuche J, Deplanque D, et al. Fibrates effect on cardiovascular risk is greater in patients with high triglyceride levels or atherogenic dyslipidemia profile. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2011; 57:267–272. This article is one of three independent meta-analyses powering the atherogenic moderate dyslipidemia cohorts from the five major fibrate trials, demonstrating the highly significant 26% to 35% RRR (P < 0.0001) of CVD events.

•• Lee M, Savera JL, Towfighic A. et al., Efficacy of fibrates for cardiovascular risk reduction in persons with atherogenic dyslipidemia: A meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2011;217:492–298. This article is one of three independent meta-analyses powering the atherogenic moderate dyslipidemia cohorts from the five major fibrate trials, demonstrating the highly significant 26% to 35% RRR (P < 0.0001) of CVD events.

Keech AC, Mitchell P, Summanen PA, et al. Effect of fenofibrate on the need for laser treatment for diabetic retinopathy (FIELD study): a randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:1687–97.

• Davis TM, Ting R, Best JD, et al. Effects of fenofibrate on renal function in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: the Fenofibrate Intervention and Event Lowering in Diabetes (FIELD) Study. Diabetologia 2011; 54: 280–290. This FIELD substudy demonstrates the reversibility of the fenofibrate rise in serum creatinine and the fenofibrate benefits to renal function in T2DM.

• Forsblom C, Hiukka A, Leinonen ES, Sundvall J, Groop PH and Taskinen MR. Effects of long-term fenofibrate treatment on markers of renal function in type 2 diabetes: the FIELD Helsinki substudy. Diabetes Care 2010; 33: 215–220. This FIELD substudy demonstrates the benefits of fenofibrate on progression of diabetic nephropathy.

Ansquer J-C, Foucher C, Rattier S, Taskinen M-R, Steiner G. Fenofibrate reduces progression to microalbuminuria over 3 years in a placebo-controlled study in type 2 diabetes: results from the Diabetes Atherosclerosis Intervention Study (DAIS). Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;45:485–93.

• ACCORD Study Group; ACCORD Eye Study Group. Effects of medical therapies on retinopathy progression in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2010; 363: 233–244. This ACCORD substudy demonstrates benefits of fenofibrate on progression of retinopathy.

Hiukka A, Westerbacka J, Leinonen ES, et al. Long-term effects of fenofibrate on carotid intima-media thickness and augmentation index in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:2190–7.

•• Reiner Z, Catapanao AL, Backer GD et al. for The Task Force for the Management of Dyslipidaemias, of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) ESC/EAS Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia. European Heart Journal 2011;32:(11)1769–1818. This 49-page article describes the newest European treatment guidelines for dyslipidemia; equivalent to NCEP-ATP in magnitude.

Disclosure

Conflicts of interest: P.D. Rosenblit: has received honoraria for Advisory Board-Consulting from Eli Lilly; research funding at his clinical trial site from AstraZeneca, Dexcom, EISAI, GlaxoSmithKline. Lifescan division of Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi, Takeda, and Tolerx; and honoraria for speaking from Abbott, Amylin, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Kowa, Merck, NovoNordisk, and Sanofi.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rosenblit, P.D. Do Persons with Diabetes Benefit from Combination Statin and Fibrate Therapy?. Curr Cardiol Rep 14, 112–124 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-011-0237-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-011-0237-7

Keywords

- Atherosclerosis

- Atherogenic dyslipidemia

- Atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype

- Bezafibrate

- Cardiovascular disease, Chylomicron remnants Combination therapies, Diabetes

- Diabetic dyslipidemia

- Dyslipidemia

- Dyslipidemia of insulin resistance

- Fenofibrate

- Fibrates

- Gemfibrozil

- HDL-C

- Hypertriglyceridemia

- Lipid-modifying therapies, Macrovascular/microvascular disease

- Residual risk reduction

- Statin-fibrate combination

- Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins

- Triglycerides

- T2DM