Abstract

A large proportion of cardiovascular events occur in individuals classified by traditional risk factors as “low-risk.” Efforts to improve early detection of coronary artery disease among low-risk individuals, or to improve risk assessment, might be justified by this large population burden. The most promising tests for improving risk assessment, or early detection, include the coronary artery calcium (CAC) score, the ankle-brachial index (ABI), and the high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP). Data regarding the role of additional testing in low-risk populations to improve early detection or to enhance risk assessment are sparse but suggest that CAC and ABI may be helpful for improving risk classification and detecting the higher-risk people from among those at lower risk. However, in the absence of clinical trials in this patient population, such as has recently been proposed, we do not recommend routine use of any additional testing or screening in low-risk individuals at this time.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(23):2388–98.

Ford ES, Capewell S. Coronary heart disease mortality among young adults in the U.S. from 1980 through 2002: concealed leveling of mortality rates. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(22):2128–32.

Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2095–128.

Force USPS. Using nontraditional risk factors in coronary heart disease risk assessment: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(7):474–82.

Shah PK. Screening asymptomatic subjects for subclinical atherosclerosis: can we, does it matter, and should we? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(2):98–105.

Lauer MS. Screening asymptomatic subjects for subclinical atherosclerosis: not so obvious. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(2):106–8.

Expert Panel on Detection E, Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in A. Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III). JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2001;285(19):2486–97.

Wilson PW, D’Agostino RB, Levy D, Belanger AM, Silbershatz H, Kannel WB. Prediction of coronary heart disease using risk factor categories. Circulation. 1998;97(18):1837–47.

Califf RM, Armstrong PW, Carver JR, D’Agostino RB, Strauss WE. 27th Bethesda Conference: matching the intensity of risk factor management with the hazard for coronary disease events. Task Force 5. Stratification of patients into high, medium and low risk subgroups for purposes of risk factor management. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996;27(5):1007–19.

Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(3):427–32. discussion 433–424.

Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, et al. Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J. 2003;24(11):987–1003.

Cooney MT, Dudina A, Whincup P, et al. Re-evaluating the Rose approach: comparative benefits of the population and high-risk preventive strategies. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil Off J Eur Soc Cardiol Work Group Epidemiol Prev Card Rehabil Exerc Physiol. 2009;16(5):541–9.

Rose G. Sick individuals and sick populations. Int J Epidemiol. 1985;14(1):32–8.

Greenland P, Alpert JS, Beller GA, et al. 2010 ACCF/AHA guideline for assessment of cardiovascular risk in asymptomatic adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2010;122(25):e584-636. This is an important review of all potential approaches to risk assessment in asymptomatic patients. It is a good source of detailed background on this subject.

Anderson TJ, Gregoire J, Hegele RA, et al. 2012 update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemia for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in the adult. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29(2):151–67. This update to previous Canadian Guidelines is an important reference source on the topics of prevention and risk assessment.

Libby P, Ridker PM, Hansson GK, Leducq Transatlantic Network on A. Inflammation in atherosclerosis: from pathophysiology to practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(23):2129–38.

Ridker PM, Rifai N, Clearfield M, et al. Measurement of C-reactive protein for the targeting of statin therapy in the primary prevention of acute coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(26):1959–65.

Sever PS, Poulter NR, Chang CL, et al. Evaluation of C-reactive protein before and on-treatment as a predictor of benefit of atorvastatin: a cohort analysis from the anglo-scandinavian cardiac outcomes trial lipid-lowering arm. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(8):717–29.

Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cardiovascular risk: rationale for screening and primary prevention. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(4B):17K–22K.

Yousuf O, Mohanty BD, Martin SS, et al. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein and cardiovascular disease: a resolute belief or an elusive link? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(5):397–408. This is a comprehensive review of the utility of C-reactive protein for cardiovascular risk. It supports a limited role for hsCRP in risk assessment.

Emerging Risk Factors C, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, et al. C-reactive protein, fibrinogen, and cardiovascular disease prediction. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(14):1310–20.

Koenig W, Lowel H, Baumert J, Meisinger C. C-reactive protein modulates risk prediction based on the Framingham Score: implications for future risk assessment: results from a large cohort study in southern Germany. Circulation. 2004;109(11):1349–53.

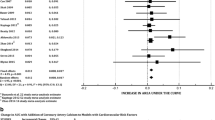

Ankle Brachial Index C, Fowkes FG, Murray GD, et al. Ankle brachial index combined with Framingham Risk Score to predict cardiovascular events and mortality: a meta-analysis. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2008;300(2):197–208.

Mohlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Moebus S, et al. Quantification of coronary atherosclerosis and inflammation to predict coronary events and all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(13):1455–64.

Yeboah J, McClelland RL, Polonsky TS, et al. Comparison of novel risk markers for improvement in cardiovascular risk assessment in intermediate-risk individuals. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2012;308(8):788–95. This is one of a small number of analyses from a large cohort comparing risk assessment approaches using different tests. It supports a conclusion that CAC is the leading contender for improving risk assessment in intermediate risk populations.

Pencina MJ, D’Agostino Sr RB, Steyerberg EW. Extensions of net reclassification improvement calculations to measure usefulness of new biomarkers. Stat Med. 2011;30(1):11–21.

Kavousi M, Elias-Smale S, Rutten JH, et al. Evaluation of newer risk markers for coronary heart disease risk classification: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(6):438–44. This paper is similar to reference 26 but applies across the entire Rotterdam cohort of mostly elderly men and women.

Lakoski SG, Greenland P, Wong ND, et al. Coronary artery calcium scores and risk for cardiovascular events in women classified as “low risk” based on Framingham risk score: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(22):2437–42.

Mohlenkamp S, Lehmann N, Greenland P, et al. Coronary artery calcium score improves cardiovascular risk prediction in persons without indication for statin therapy. Atherosclerosis. 2011;215(1):229–36.

Desai CS, Ayers CR, Budoff M, et al. Improved coronary heart disease risk prediction with coronary artery calcium in low-risk women: a meta-analysis of four cohorts. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(10):E995–5.

Wilson JM. The evaluation of the worth of early disease detection. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1968;16 Suppl 2:48–57.

Bhatti SK, Dinicolantonio JJ, Captain BK, Lavie CJ, Tomek A, O’Keefe JH. Neutralizing the adverse prognosis of coronary artery calcium. Mayo Clin Proc Mayo Clin. 2013;88(8):806–12.

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists C, Mihaylova B, Emberson J, et al. The effects of lowering LDL cholesterol with statin therapy in people at low risk of vascular disease: meta-analysis of individual data from 27 randomised trials. Lancet. 2012;380(9841):581–90.

Ambrosius WT, Polonsky TS, Greenland P, et al. Design of the value of imaging in enhancing the wellness of your heart (VIEW) trial and the impact of uncertainty on power. Clin Trials. 2012;9(2):232–46. This is a provocative proposal for a large-scale trial of coronary artery calcium testing (screening) in asymptomatic low-risk individuals. It is an important “thought-piece” on this topic.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

Conflict of Interest

Chintan S. Desai, Roger S. Blumenthal, and Philip Greenland declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Coronary Heart Disease

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Desai, C.S., Blumenthal, R.S. & Greenland, P. Screening Low-Risk Individuals for Coronary Artery Disease. Curr Atheroscler Rep 16, 402 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-014-0402-8

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-014-0402-8