Opinion statement

Inhibitors of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) have emerged as a new class of anti-cancer drugs, specifically for malignancies bearing aberrations of the homologous recombination pathway, like those with mutations in the BRCA 1 and BRCA 2 genes. Olaparib, a potent PARP1 and PARP2 inhibitor, has been shown to significantly increase progression-free survival (PFS) in women with recurrent ovarian cancer related to a germline BRCA mutation and is currently approved fourth-line treatment in these patients. PARP inhibitors (PARPi) target the genetic phenomenon known as synthetic lethality to exploit faulty DNA repair mechanisms. While ovarian cancer is enriched with a population of tumors with known homologous recombination defects, investigations are underway to help identify pathways in other gynecologic cancers that may demonstrate susceptibility to PARPi through synthetically lethal mechanisms. The ARIEL2 trial prospectively determined a predictive assay to identify patients with HRD. The future of cancer therapeutics will likely incorporate these HRD assays to determine the best treatment plan for patients. While the role of PARPi is less clear in non-ovarian gynecologic cancers, the discovery of a predictive assay for HRD may open the door for clinical trials in these other gynecologic cancers enriched with patients with HRD. Identification of patients with tumors deficient in homologous repair or have HRD-like behavior moves cancer treatment towards individualized therapies in order to maximize treatment effect and quality of life for women living with gynecologic cancers.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29.

Bridges CB. The origin of variation. The American Naturalist. 1922:13.

Lord CJ, Ashworth A. Mechanisms of resistance to therapies targeting BRCA-mutant cancers. Nat Med. 2013;19:1381–8.

Dobzhansky T. Genetics of natural populations. Xiii. Recombination and variability in populations of drosophila pseudoobscura. Genetics. 1946;31:269–90. The first description in the literature of the concept of synthetic lethality.

Tischler J, Lehner B, Fraser AG. Evolutionary plasticity of genetic interaction networks. Nat Genet. 2008;40:390–1.

Hartwell LH, Szankasi P, Roberts CJ, Murray AW, Friend SH. Integrating genetic approaches into the discovery of anticancer drugs. Science. 1997;278:1064–8.

Kaelin WG. The concept of synthetic lethality in the context of anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:689–98.

Tewari KS, Monk BJ. The 21st century handbook of clinical ovarian cancer. Cham: Adis; 2015.

Amé JC, Rolli V, Schreiber V, Niedergang C, Apiou F, Decker P, et al. PARP-2, a novel mammalian DNA damage-dependent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17860–8.

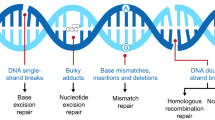

Dantzer F, Schreiber V, Niedergang C, Trucco C, Flatter E, De La Rubia G, et al. Involvement of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in base excision repair. Biochimie. 1999;81:69–75.

Gibson BA, Kraus WL. New insights into the molecular and cellular functions of poly(ADP-ribose) and PARPs.

Leung AKL. Poly(ADP-ribose): an organizer of cellular architecture. J Cell Biol. 2014;205:613–9.

Isabelle M, Moreel X, Gagné JP, Rouleau M, Ethier C, Gagné P, et al. Investigation of PARP-1, PARP-2, and PARG interactomes by affinity-purification mass spectrometry. Proteome Sci. 2010;8:22.

Wang M, Wu W, Rosidi B, Zhang L, Wang H, Iliakis G. PARP-1 and Ku compete for repair of DNA double strand breaks by distinct NHEJ pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:6170–82.

Haince JF, McDonald D, Rodrigue A, Déry U, Masson JY, Hendzel MJ, et al. PARP1-dependent kinetics of recruitment of MRE11 and NBS1 proteins to multiple DNA damage sites. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1197–208.

Hirschhorn R. In vivo reversion to normal of inherited mutations in humans. J Med Genet. 2003;40:721–8.

Schultz N, Lopez E, Saleh-Gohari N, Helleday T. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1) has a controlling role in homologous recombination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:4959–64.

Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, Tutt AN, Johnson DA, Richardson TB, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917–21.

Bryant HE, Schultz N, Thomas HD, Parker KM, Flower D, Lopez E, et al. Specific killing of BRCA2-deficient tumours with inhibitors of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. Nature. 2005;434:913–7.

McNeish IA, Oza AM, Coleman RL, Scott CL, Konecny GE, Tinker A, et al. Results of ARIEL2: A Phase 2 trial to prospectively identify ovarian cancer patients likely to respond to rucaparib using tumor genetic analysis. ASCO Annual Meeting. Chicago, Illinois: J Clin Oncol 33, 2015 (suppl; abstr 5508); 2015. The first prospectively determined HRD assay in a PARPi clinical trial and confirmed with tumor reponse to rucaparib.

Stambolic V, Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Brothers GM, Mirtsos C, Sasaki T, et al. Negative regulation of PKB/Akt-dependent cell survival by the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cell. 1998;95:29–39.

Wu X, Senechal K, Neshat MS, Whang YE, Sawyers CL. The PTEN/MMAC1 tumor suppressor phosphatase functions as a negative regulator of the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:15587–91.

Shen WH, Balajee AS, Wang J, Wu H, Eng C, Pandolfi PP, et al. Essential role for nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal integrity. Cell. 2007;128:157–70.

Mendes-Pereira AM, Martin SA, Brough R, McCarthy A, Taylor JR, Kim JS, et al. Synthetic lethal targeting of PTEN mutant cells with PARP inhibitors. EMBO Mol Med. 2009;1:315–22.

Dedes KJ, Wetterskog D, Mendes-Pereira AM, Natrajan R, Lambros MB, Geyer FC, et al. PTEN deficiency in endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinomas predicts sensitivity to PARP inhibitors. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:53ra75.

Hegan DC, Lu Y, Stachelek GC, Crosby ME, Bindra RS, Glazer PM. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase down-regulates BRCA1 and RAD51 in a pathway mediated by E2F4 and p130. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2201–6.

Hassumi-Fukasawa MK, Miranda-Camargo FA, Zanetti BR, Galano DF, Ribeiro-Silva A, Soares EG. Expression of BAG-1 and PARP-1 in precursor lesions and invasive cervical cancer associated with human papillomavirus (HPV). Pathol Oncol Res. 2012;18:929–37.

Weaver AN, Cooper TS, Rodriguez M, Trummell HQ, Bonner JA, Rosenthal EL, et al. DNA double strand break repair defect and sensitivity to poly ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibition in human papillomavirus 16-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2015;6:26995–7007.

Fong PC, Boss DS, Yap TA, Tutt A, Wu P, Mergui-Roelvink M, et al. Inhibition of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in tumors from BRCA mutation carriers. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:123–34. Original phase I trial that determined MTD of olaparib 400mg twice daily and confirmed that its clinical benefit rate was associated with platinum sensitivity.

Fong PC, Yap TA, Boss DS, Carden CP, Mergui-Roelvink M, Gourley C, et al. Poly(ADP)-ribose polymerase inhibition: frequent durable responses in BRCA carrier ovarian cancer correlating with platinum-free interval. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2512–9.

Tutt A, Robson M, Garber JE, Domchek SM, Audeh MW, Weitzel JN, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and advanced breast cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:235–44.

Audeh MW, Carmichael J, Penson RT, Friedlander M, Powell B, Bell-McGuinn KM, et al. Oral poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer: a proof-of-concept trial. Lancet. 2010;376:245–51.

Yang D, Khan S, Sun Y, Hess K, Shmulevich I, Sood AK, et al. Association of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations with survival, chemotherapy sensitivity, and gene mutator phenotype in patients with ovarian cancer. JAMA. 2011;306:1557–65.

Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive relapsed ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1382–92.

Kaye SB, Lubinski J, Matulonis U, Ang JE, Gourley C, Karlan BY, et al. Phase II, open-label, randomized, multicenter study comparing the efficacy and safety of olaparib, a poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor, and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin in patients with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations and recurrent ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:372–9.

Ledermann J, Harter P, Gourley C, Friedlander M, Vergote I, Rustin G, et al. Olaparib maintenance therapy in patients with platinum-sensitive relapsed serous ovarian cancer: a preplanned retrospective analysis of outcomes by BRCA status in a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:852–61. Randomized phase II trial, known as Study 19, demonstrated the PFS benefit of olaparib in the maintenance setting, especially in BRCA mutation carriers. It serves as the precursor for the SOLO-1 trial.

Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, Audeh MW, Friedlander M, Balmaña J, et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:244–50. Multicenter phase II trial, known as Study 42, that lead to the FDA approval of olaparib as fourth line therapy for women with BRCA-related ovarian cancer.

Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves Lynparza to treat advanced ovarian cancer. http://www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm427554.htm. Access date: September 10, 2015.

Rottenberg S, Jaspers JE, Kersbergen A, van der Burg E, Nygren AO, Zander SA, et al. High sensitivity of BRCA1-deficient mammary tumors to the PARP inhibitor AZD2281 alone and in combination with platinum drugs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17079–84.

Evers B, Drost R, Schut E, de Bruin M, van der Burg E, Derksen PW, et al. Selective inhibition of BRCA2-deficient mammary tumor cell growth by AZD2281 and cisplatin. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3916–25.

Hay T, Matthews JR, Pietzka L, Lau A, Cranston A, Nygren AO, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 inhibitor treatment regresses autochthonous Brca2/p53-mutant mammary tumors in vivo and delays tumor relapse in combination with carboplatin. Cancer Res. 2009;69:3850–5.

Joenje H, Patel KJ. The emerging genetic and molecular basis of fanconi anaemia. Nat Rev Genet. 2001;2:446–57.

Grompe M, D’Andrea A. Fanconi anemia and DNA repair. Hum Mol Genet. 2001;10:2253–9.

D’Andrea AD, Grompe M. The fanconi anaemia/BRCA pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:23–34.

Pothuri B. BRCA1- and BRCA2-related mutations: therapeutic implications in ovarian cancer. Ann Oncol. 2013;24 Suppl 8:viii22–7.

Del Conte G, Sessa C, von Moos R, Viganò L, Digena T, Locatelli A, et al. Phase I study of olaparib in combination with liposomal doxorubicin in patients with advanced solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:651–9.

Lee JM, Hays JL, Annunziata CM, Noonan AM, Minasian L, Zujewski JA, et al. Phase I/Ib study of olaparib and carboplatin in BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation-associated breast or ovarian cancer with biomarker analyses. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:dju089.

Oza AM, Cibula D, Benzaquen AO, Poole C, Mathijssen RH, Sonke GS, et al. Olaparib combined with chemotherapy for recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:87–97. Randomized phase II trial, known as Study 41, that demonstrated improved PFS of olaparib with chemotherapy compared to carboplatin/paclitaxel alone.

Rivkin SE, Iriarte D, Sloan H, Wiseman C, Moon J. Phase Ib/II with expansion of patients at the MTD study of olaparib plus weekly (metronomic) carboplatin and paclitaxel in relapsed ovarian cancer patients. ASCO Annual Meeting. Chicago, IL J Clin Oncol 32:5s, 2014 (suppl; abstr 5527).

Giansanti V, Donà F, Tillhon M, Scovassi AI. PARP inhibitors: new tools to protect from inflammation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2010;80:1869–77.

Khanna KK, Jackson SP. DNA double-strand breaks: signaling, repair and the cancer connection. Nat Genet. 2001;27:247–54.

Liu JF, Tolaney SM, Birrer M, Fleming GF, Buss MK, Dahlberg SE, et al. A Phase 1 trial of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor olaparib (AZD2281) in combination with the anti-angiogenic cediranib (AZD2171) in recurrent epithelial ovarian or triple-negative breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2972–8. The initial phase I trial that established the MTD of olaparib to be 200mg BID in combination with cedrianib 30mg daily.

Matulonis UA, Berlin S, Ivy P, Tyburski K, Krasner C, Zarwan C, et al. Cediranib, an oral inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor kinases, is an active drug in recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and peritoneal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5601–6.

Liu JF, Barry WT, Birrer M, Lee JM, Buckanovich RJ, Fleming GF, et al. Combination cediranib and olaparib versus olaparib alone for women with recurrent platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer: a randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1207–14. Randomized phase II trial demonstrating significantly improved PFS of combination cediranib and olaparib compared to olaparib alone.

Wagner LM. Profile of veliparib and its potential in the treatment of solid tumors. Oncol Targets Ther. 2015;8:1931–9.

Coleman RL, Sill MW, Bell-McGuinn K, Aghajanian C, Gray HJ, Tewari KS, et al. A phase II evaluation of the potent, highly selective PARP inhibitor veliparib in the treatment of persistent or recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer in patients who carry a germline BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutation - An NRG Oncology/Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Gynecol Oncol. 2015;137:386–91. Phase II trial demonstrating activity of veliparib in heavily pretreated patients with BRCA-related ovarian cancer.

Kummar S, Ji J, Morgan R, Lenz HJ, Puhalla SL, Belani CP, et al. A phase I study of veliparib in combination with metronomic cyclophosphamide in adults with refractory solid tumors and lymphomas. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1726–34.

Kummar S, Chen A, Ji J, Zhang Y, Reid JM, Ames M, et al. Phase I study of PARP inhibitor ABT-888 in combination with topotecan in adults with refractory solid tumors and lymphomas. Cancer Res. 2011;71:5626–34.

Tan AR, Toppmeyer D, Stein MN, Moss RA, Gounder M, Lindquist DC, et al. Phase I trial of veliparib, (ABT-888), a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor, in combination with doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide in breast cancer and other solid tumors. ASCO Annual Meeting. Chicago, Illinois: J Clin Oncol 29: (suppl; abstr 3041); 2011.

Liu FW, Cripe J, Tewari KS. Anti-angiogenesis therapy in gynecologic malignancies. Oncology (Williston Park). 2015;29:350–60.

Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, Fleming GF, Monk BJ, Huang H, et al. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473–83.

Sandhu SK, Schelman WR, Wilding G, Moreno V, Baird RD, Miranda S, et al. The poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor niraparib (MK4827) in BRCA mutation carriers and patients with sporadic cancer: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:882–92.

Matulonis U, Mahner S, Wenham RM, Ledermann JA, Monk BJ, Del Campo JM, et al. A phase 3 randomized double-blind trial of maintenance with niraparib versus placebo in patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer (ENGOT-OV16/NOVA trial). ASCO Annual Meeting. Chicago, Illinois: J Clin Oncol 32:5s, 2014 (suppl; abstr TPS5625); 2014. A phase III double-blind, placebo-controlled, 2:1 randomized trial of maintenance niraparib versus placebo in patients with recurrent platinum sensitive high grade serous ovarian cancer or known to have a germline BRCA mutation.

Moore KN, Zhang Z-Y, Agarwal S, Patel MR, Burris HA, Martell RE, et al. Food effect substudy of a phase 3 randomized double-blind trial of maintenance with niraparib (MK4827), a poly(ADP)ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitor versus placebo in patients with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. ASCO Annual Meeting. Chicago, Illinois: J Clin Oncol 32: (suppl; abstr e16531), 2014.

Ihnen M, zu Eulenburg C, Kolarova T, Qi JW, Manivong K, Chalukya M, et al. Therapeutic potential of the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor rucaparib for the treatment of sporadic human ovarian cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:1002–15.

Shapiro G, Kristeleit R, Middleton M, Burris H, Rhoda Molife L, Jeff E, et al. Pharmacokinetics of orally administered rucaparib in patients with advanced solid tumors. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:A218. Proceedings of AACR/NCI/EORTC targeted therapies meeting.

Kristeleit R, Shapira-Frommer R, Burris H, Patel MR, Lorusso P, Oza AM, et al. Phase 1/2 study of oral rucaparib: updated phase 1 and preliminary phase 2 results. Ann Oncol. 2014;25(suppl_4):iv305–26. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdu338. ESMO Annual Meeting. Madrid, Spain.

Swisher EM, Oza AM, Coleman RL, Scott C, Lin K, Dominy E, et al. Tumor BRCA mutation or high genomic LOH identify ovarian cancer patients likely to respond to rucaparib: interim results for ARIEL2 clinical trial. Chicago: Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer; 2015.

Shen Y, Rehman FL, Feng Y, Boshuizen J, Bajrami I, Elliott R, et al. BMN 673, a novel and highly potent PARP1/2 inhibitor for the treatment of human cancers with DNA repair deficiency. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:5003–15.

De Bono JS, Mina LA, Gonzalez M, Curtin NJ, Wang E, Henshaw JW, et al. First-in-human trial of novel oral PARP inhibitor BMN 673 in patients with solid tumors. ASCO Annual Meeting. Chicago, Illinois: J Clin Oncol 31 (suppl; abstr 2580); 2013.

Haluska P, Timms KM, AlHilli M, Wang Y, Hartman AM, Jones J, et al. Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) score and niraparib efficacy in high grade ovarian cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50(supp 6 abst 214):72. 26th EORTC–NCI–AACR Symposium on Molecular Targets and Cancer Therapies. Madrid, Spain.

Watkins JA, Irshad S, Grigoriadis A, Tutt AN. Genomic scars as biomarkers of homologous recombination deficiency and drug response in breast and ovarian cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:211.

Birkbak NJ, Wang ZC, Kim JY, Eklund AC, Li Q, Tian R, et al. Telomeric allelic imbalance indicates defective DNA repair and sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:366–75.

Mulligan JM, Hill LA, Deharo S, Irwin G, Boyle D, Keating KE, et al. Identification and validation of an anthracycline/cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy response assay in breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2014;106:djt335.

Telli ML, Jensen KC, Vinayak S, Kurian AW, Lipson JA, Flaherty PJ, et al. Phase II study of gemcitabine, carboplatin, and iniparib as neoadjuvant therapy for triple-negative and BRCA1/2 mutation-associated breast cancer with assessment of a tumor-based measure of genomic instability: PrECOG 0105. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1895–901.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Gynecologic Cancers

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, F.W., Tewari, K.S. New Targeted Agents in Gynecologic Cancers: Synthetic Lethality, Homologous Recombination Deficiency, and PARP Inhibitors. Curr. Treat. Options in Oncol. 17, 12 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-015-0378-9

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11864-015-0378-9