Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to offer a comprehensive and useful typology of innovation ecosystems. While recent conceptual efforts have been allocated to delineating innovation ecosystems from other phenomena, much less systematic attention has been given to the diversity found within the innovation ecosystem realm. We run a thematic analysis of systematic literature reviews and collect 34 specific types of innovation ecosystems. We expand this list with criteria-derived complementary types and propose a set of 50 distinct innovation ecosystem varieties. Next, we identify the 14 typology criteria used so far in the literature, thematically analyse them and aggregate them into a set useful for further rigorous scrutiny and for the incremental collection of empirical findings. Innovation ecosystems can thus be categorized into (1) life cycle, (2) structure, (3) innovation focus, (4) scope of activities, and (5) performance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

J.F. Moore was the first to use the concept of a business ecosystem, wherein organizations “coevolve capabilities around a new innovation: they work cooperatively and competitively to support new products, satisfy customer needs, and eventually incorporate the next round of innovations” (Moore 1993, p. 76). Moore’s seminal paper triggered a whole new way of perceiving the business environment, which, in contrast to the traditional industry organization framework developed by M.E. Porter, considers the environment as a system not limited to one single industry, not limited only to organizations, and mutually interdependent (Teece 2007).

Prior literature reviews have identified several different varieties of ecosystems, such as industrial, innovation, business, digital and entrepreneurial ecosystems (Pilinkiene and Maciulis 2014); business, knowledge and innovation ecosystems (Valkokari 2015); business, innovation, entrepreneurial & start-up, platform and service ecosystems (Aarikka-Stenroos and Ritala 2017); and business, innovation, entrepreneurial (entrepreneurship) and knowledge ecosystems (Scaringella and Radziwon 2018). This paper focuses on innovation ecosystems (IE) as they are gaining in importance and popularity in both innovation and strategic management. Furthermore, as they are crucial for development of new or young ventures and increase in the likelihood of firm survival, therefore for entrepreneurship at individual, organizational, and regional levels (Kraus et al. 2020b).

After two decades of fruitful application of the innovation ecosystem concept in a variety of contexts and ways, there are presently a wide array of definitions for the term (Wei et al. 2020), with only very recent efforts aimed at forging a consensual definition (Granstrand and Holgersson 2020; Rabelo and Bernus 2015; Valkokari 2015). Variations in definitions hamper dialogue across streams of research, disconnect conversations, confuse (Maitlis and Christianson 2014), impede the accumulation of coherent empirical evidence and the development of measurement, and hinder research progress in general (Venkatraman 1989). It is therefore critically important to rigorously define concepts and look for consensus in emerging fields of research (Kang et al. 2019). Consensual definitions are essential in academic disciplines in order to maintain their distinctiveness and collective identity (Nag et al. 2007). This process is challenging due to ecosystems’ substantially polymorphic nature (Aarikka-Stenroos and Ritala 2017; Scaringella and Radziwon 2018; Tsujimoto et al. 2018; Valkokari 2015), which results in overlaps among different types of ecosystems (Aarikka-Stenroos and Ritala 2017), and partial overlaps with similar concepts such as networks, chains or clusters (Carayannis and Campbell 2009). Two conceptual challenges are related to defining innovation ecosystems: delineation and typology. While delineation has recently received rigorous attention (Granstrand and Holgersson 2020), typology has not. Our study aims to fill this gap and thus contribute to the advancement of innovation ecosystem research.

Therefore, this paper aims to offer a synthesis of innovation ecosystem delineation and to develop a typology useful in further empirical research. Using a critical analysis of systematic literature reviews and a thematic analysis, our study provides 5 generic typology criteria, encapsulating 14 literature-derived typology criteria, and identifies 50 different types of innovation ecosystems.

The remainder of this paper is divided into four sections. The following section focuses on delineating innovation ecosystems. The third section explains our methodological approach. In the fourth section we outline the typology emerging from our thematic analysis and the developmental process. Conventionally, the last part of the paper points to the theoretical contributions, outlines the main limitations and identifies directions for further research.

2 Understanding of innovation ecosystems

The last decade has witnessed dynamic growth in the popularity of innovation ecosystems research among scholars (Beliaeva et al. 2019; Kang et al. 2019; Liguori et al. 2019; Su et al. 2018; Xu et al. 2018; Bacon et al. 2020) accompanied by a “burgeoning interest” among practitioners and policymakers (Dedehayir et al. 2016, p. 9). Innovation ecosystems are depicted as a dominant concept in innovation management (Jucevicius et al. 2016), allowing research in the field of innovation management to be carried out in a particularly timely and accurate manner. The ecosystem concept takes into account the progressive externalization, systemic co-implementation and networking of innovation (Ritala and Almpanopoulou 2017, p. 39) typical for the current business environment. Innovation ecosystems are attributed with exerting a multilevel impact on innovation: they enhance innovation capability (Pellikka and Ali-Vehmas 2018) and the innovation performance of actors (Song 2016), as well as increasing the innovation performance of the entire ecosystem (Talmar et al. 2018). Innovation ecosystems correspond perfectly with the recent interest in various forms of customer engagement in new product development processes. What is more, communities of interest and communities of users are also viewed as a meaningful component of innovation ecosystems (Autio and Thomas 2014; Russell and Smorodinskaya 2018). All in all, the involvement of additional actors such as customers and communities in innovation ecosystems is a distinctive feature when compared to other types of ecosystems (Gomes et al. 2018; Oh et al. 2016; Valkokari 2015).

Innovation ecosystems have also become a relevant research stream in strategic management as they impact a firm’s strategy and performance (Luo 2018) through an increase in firms’ profitability, shorter time-to-market, enhanced market access (Pellikka and Ali-Vehmas 2018) and improved new product development (Bouncken et al. 2018). From a more longitudinal perspective, engagement in an innovation ecosystem brings strategic advantages stemming from relationships with other actors through competition, cooperation or coopetition. Competitive advantages accrue on the part of those involved in innovation ecosystems as opposed to those outside of innovation ecosystems. Collaborative advantages are rooted in relational rents (Dyer and Singh 1998) as well as in social relationships of manegers (Glińska-Neweś et al. 2018), and are exploited under relational strategies (Zakrzewska-Bielawska 2019). It is emphasized that they encourage radical innovations (Bouncken et al. 2018) as well as innovations of business models (Bouncken and Fredrich 2016). At the same time, coopetition within the innovation ecosystem brings the advantages of both competition and cooperation (Bacon et al. 2020), and is usually at more beneficial levels than those based on being “just competitive” or “just cooperative” (Bouncken et al. 2015; Ritala et al. 2013, 2016; Gawer and Cusumano 2014). Finally, when compared to other types of ecosystems, innovation ecosystems seem to be the most strategically oriented (Beliaeva et al. 2019; Granstrand and Holgersson 2020). The latest findings from a review of the literature suggest that four out of six IE contexts refer directly to strategy, i.e. ecosystem strategy, innovation strategy, management strategy and orchestration strategy (Yaghmaie and Vanhaverbeke 2019). The popularity of the innovation ecosystem in various research streams adds to the ambiguity of the concept. Below, we delineate innovation ecosystems from other ecosystems and offer a narrow definition focused on their key component, that is relationships (Granstrand and Holgersson 2020).

2.1 Delineating innovation ecosystems from other ecosystems

The use of ecosystem concepts and related approaches has spawned studies across the literature (Adner 2017; Tsujimoto et al. 2018; Liguori et al. 2019). This development induces an increase in knowledge, including the emergence and exploration of different types of ecosystems (Aarikka-Stenroos and Ritala 2017; Pilinkiene and Maciulis 2014; Scaringella and Radziwon 2018; Valkokari 2015), acknowledged as overlapping (Scaringella and Radziwon 2018), intertwined (Valkokari 2015) and interdependent (Xu et al. 2018). Some scholars propose viewing innovation ecosystems as a meta-ecosystem comprising of three mutually intertwined layers: a science ecosystem, a knowledge ecosystem and a business ecosystem (Xu et al. 2018). This view offers the benefit of complexity, and the prevalence of the innovation ecosystem over others qualifies it as a higher-order concept.

However, a sustained research stream identifies several delineation criteria that distinguish innovation ecosystems from other ecosystems (Aarikka-Stenroos and Ritala 2017; Pilinkiene and Maciulis 2014; Rohrbeck et al. 2009; Scaringella and Radziwon 2018; Valkokari 2015; Vasconcelos Gomes et al. 2018). Clarysse et al. (2014) differentiate knowledge and innovation ecosystems using several criteria, that is: aims, relationships and actors. Pilinkiene and Maciulis (2014) use type of environment, actors, micro and macro outputs, and key success indicators to differentiate industrial, innovation, business, digital and entrepreneurial ecosystems. Valkokari (2015) identifies three distinct types of ecosystems: business, innovation and knowledge, by analysing their aims, internal relationships, levels of interconnection of actors, roles adopted by actors, and the general logic of each ecosystem type. In a more territorial perspective, Scaringella and Radziwon (2018) clearly delineate innovation, business, knowledge and entrepreneurial ecosystems in terms of geographical scope, values, stakeholders, importance and types of economic and social issues, knowledge and outcomes. Finally, Aarikka-Stenroos and Ritala (2017) point to geographical scope, actors, and actor-related issues (e.g. particular goals, values and beliefs followed by them) as a reasoned approach for distinguishing between business, innovation, entrepreneurial, platform and service ecosystems. The pool of differentiation criteria is quite broad, which suggests that scholars see innovation ecosystems as different in many respects from other ecosystems.

Furthermore, value creation and value capture appear as key characteristics for delineating innovation ecosystems (Gomes et al. 2018). An important criterion that allows business, knowledge and innovation ecosystems to be distinguished is the type of actors’ and ecosystem’s orientation towards current and/or future customer value creation (Valkokari 2015). We posit that the underlying basis of co-created value can also be used as a differentiation criterion. Different types of co-creation relationships constitute different ecosystems. Indeed, business ecosystems consist of co-creation relationships aimed at joint creation of up-to-date and competitive value propositions. In the case of knowledge ecosystems, new, original and jointly created knowledge is the root of the value co-created by actors. In turn, innovation ecosystems operating as co-innovation processes co-create value based on co-innovation. In this perspective, every ecosystem targets value co-creation and consists of co-creation relationships.

In innovation ecosystems, co-created value is based on innovations, specifically on co-innovations, which are reached through the exploitation of innovation co-creation relationships. Innovation co-creation relationships are a specific type of co-creation relationships (Klimas 2019; labelled also as ecosystem relationships—Vargo 2009), as one of the external, relational resources of an organization targeting value co-creation through the implementation of co-innovation processes. These relationships are instrumental in innovation processes with the support of external partners in delivering innovations to the market. We propose that innovation co-creation relationships are distinctive to the innovation ecosystem concept as they allow the actors and the entire ecosystem to co-create value resulting from co-innovation (Aarikka-Stenroos and Ritala 2017).

In innovation ecosystems, other types of co-creation relationships are also utilized, such as: knowledge co-creation relationships distinctive for knowledge ecosystems, business model co-creation relationships distinctive for business ecosystems, or venture co-creation relationships distinctive for entrepreneurial ecosystems (Beliaeva et al. 2019; Kang et al. 2019). Indeed, the various types of ecosystems are acknowledged as being highly interpenetrating (Scaringella and Radziwon 2018; Valkokari 2015; Xu et al. 2018). However, without innovation co-creation relationships, innovation ecosystems cannot be delineated from others.

2.2 Defining the innovation ecosystem concept

Innovation ecosystems differ significantly and multidimensionally from other types of ecosystems (Ferasso et al. 2018; Gomes et al. 2018), and are attracting a strong and rapidly growing interest among scholars, practitioners and policymakers (Tsujimoto et al. 2018; Yaghmaie and Vanhaverbeke 2019). This results in a rapidly growing stock of knowledge including theoretical propositions, conceptual considerations, analyses of practical examples and findings from explorative case studies. At the same time, the current knowledge on the innovation ecosystem lacks integration (Durst and Poutanen 2013; Gomes et al. 2018; Granstrand and Holgersson 2020; Bacon et al. 2020). Solid, coherent knowledge on innovation ecosystems is nascent and remains fragmentary (Russell and Smorodinskaya 2018). Indeed, it is still described as frugal and ambiguous when compared to business ecosystems literature (Oh et al. 2016). A major reason for this is the diversity of existing innovation ecosystems. Conceptual rigour and clarity call for its varied manifestations to be delineated from related concepts, its key characteristics to be identified, and identification of classification criteria to be conducted.

Generally, innovation ecosystems are seen as the “most prominent type of environment” (Rabelo and Bernus 2015, p. 2250), crossing the borders of a single industry or sector (Autio and Thomas 2014) and giving a multidimensional, complex context for any entrepreneurial activities (Vasconcelos Gomes et al. 2018) that result in innovation (Beliaeva et al. 2019; Valkokari 2015). Nonetheless, as in the case of ecosystems, the literature does not provide one widely recognized definition of the innovation ecosystem. The diversity and abundance of conceptualizations, definitions, operationalizations, structural approaches or even terms and labels (Oh et al. 2016) is substantiated in available systematic literature reviews, including interpretative (Tsujimoto et al. 2018), hybrid (Gomes et al. 2018) and meta-analytical (Ferasso et al. 2018) ones. Nevertheless, prior conceptualizations are mostly compatible with one another (Gomes et al. 2018), and the adoption of a particular conceptualization depends on the reference theories underlying the particular aspects of innovation ecosystems explored in a particular study (Shaw and Allen 2018). Therefore, one can find the chaos (e.g. see different views presented in Table 2 in Wei et al. 2020, p. 5) that exists in the definitions and labels used (Gomes et al. 2018) as a rationale for paying greater attention to conceptual choices and requirements of methodological rigour (Ritala and Almpanopoulou 2017). Recent studies outline several flaws in the available conceptualisations, and from rigorous identification of the shortcomings of prior works, derive a definition that underscores the importance of relationships, actors and artifacts (Granstrand and Holgersson 2020).

Given the content of the existing definitions of innovation ecosystems, the similarities among them, and the main foci adopted by the authors (Table 1), we see the innovation ecosystem as a cooperation environment surrounding the innovation activities of its co-evolving actors, organized across co-innovation processes, and resulting in co-creation of new value delivered through innovation.

Innovation ecosystems are not restricted either to one co-innovation process or to innovation processes carried out by one focal actor. In our understanding, the innovation ecosystem encapsulates the innovation processes run by involved actors if these processes are deployed with external support from the innovation ecosystem. Therefore, we extend the construct beyond an ego-centric perspective, where innovation ecosystems are defined from the focal firm’s perspective (Holgersson et al. 2018; Jucevičius and Grumadaitė 2014; Pombo-Juárez et al. 2017; Song 2016; Yaghmaie and Vanhaverbeke 2019). We incorporate parallel innovations within the boundaries of innovation ecosystems (Rubens et al. 2011, p. 1743).

The proposed way of understanding the innovation ecosystem corresponds to a recent ecosystem definition: “the alignment structure of the multilateral set of partners that need to interact in order for a focal value proposition to materialize” (Adner 2017, p. 40). Our definition focuses on the scope of interaction, which is the joint realization of innovation processes within innovation ecosystems. When engaging other actors, these activities become co-innovation processes. Secondly, within innovation ecosystems, the co-created and delivered value is based on co-innovations.Footnote 1 Finally, innovation ecosystem actors can engage in either cooperation or coopetition. Indeed, many actions undertaken within innovation ecosystems bring competitors (Holgersson et al. 2018; Talmar et al. 2018; Walrave et al. 2018; Bacon et al. 2020), even direct ones (Planko et al. 2017), to collaborate with one another because of the need for innovation.

Summing up, the literature published to date displays a broad variety in the way innovation ecosystems are understood (Durst and Poutanen 2013; Granstrand and Holgersson 2020). Given the wide range of terminological (Oh et al. 2016), definitional (Gomes et al. 2018; Granstrand and Holgersson 2020; Yaghmaie and Vanhaverbeke 2019), and methodological (Aarikka-Stenroos and Ritala 2017; Ritala and Almpanopoulou 2017) inconsistencies, it is important to critically analyse and synthesize the existing state of knowledge to pave the way for accumulation of effective empirical knowledge. In particular, we deem it relevant to pay attention to the types of innovation ecosystems, how they are understood and the criteria used to group them. Among the gaps and shortcomings discussed in the literature on innovation ecosystems, there is a clear indication that “the literature does not yield a firm typology of innovation ecosystems” even though “the term is mentioned in several contexts” (Oh et al. 2016, p. 3). Our study addresses this gap.

3 Methodology

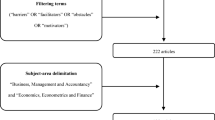

Our study aims to develop a typology of innovation ecosystems useful in further empirical research. To this end, it is necessary to identify relevant differentiation criteria and corresponding types of innovation ecosystems. We start by identifying a literature-derived inventory of types and typology criteria. Next, we conduct a thematic analysis (Czakon and Czernek-Marszałek 2020) to aggregate typology criteria by similarity and relatedness. Finally, we extend the list of innovation ecosystem types with logically complementary types according to each of the typology criteria. Our approach to reviewing is qualitative as the field of interest in IE is too recent to carry out extensive literature reviews by applying bibliometric analyses or meta-synthesis to provide more quantified conclusions about the current stock of knowledge (King and He 2005). Differently from literature reviews on entrepreneurship (Ferreira et al. 2019; Kraus et al. 2020a), knowledge management (Pellegrini et al. 2020), or entrepreneurial ecosystems (Kang et al. 2019; Liguori et al. 2019), the field of innovation ecosystems requires integration (Granstrand and Holgersson 2020) as it is too early for systematization, cluster aggregation or citation mapping.

3.1 Literature review process

The primary source of the state-of-the-art knowledge used in our study were previously published literature reviews on innovation ecosystems. Prior literature reviews have summarised and integrated the current stock of knowledge on innovation ecosystems in terms of adopted theoretical frameworks (e.g. Yaghmaie and Vanhaverbeke 2019), findings and contributions (Durst and Poutanen 2013; Ferasso et al. 2018; Gomes et al. 2018); relevant cognitive gaps (Gomes et al. 2018), types of published works (Dedehayir et al. 2016), applied research methods (Gomes et al. 2018), adopted conceptual and industry context (Yaghmaie and Vanhaverbeke 2019), and the most promising benefits and main limitations of the application of the innovation ecosystem approach within innovation and strategic management research (Oh et al. 2016). Furthermore, a review carried out by Gomes and colleagues (Gomes et al. 2018) provides insightful findings from bibliometric analyses, such as the identification of seminal papers and the most often cited authors, analysis of networks of references, co-citations, and cross-citations which might be useful when making any conceptual, methodological or research choices. Thus we were able to map how innovation ecosystem scholars view the concept, what is their shared understanding and how this understanding can feed further research (Roth et al. 2017).

We decided to start with a critical, thematic analysis focused on several available literature reviews that are rigorous in terms of applying a systematic approach or hybrid approach linking qualitative content analysis with quantitative bibliometric techniques. Such an approach is used in research domains that are similar by novelty, are rapidly growing and are conceptually diverse (Czakon et al. 2020). Typically, in the systematic approach (Ferreira et al. 2019; Pellegrini et al. 2020; Kraus et al. 2020a), two academic databases are used (Ebsco and Scopus) to gather relevant and reliable reviews covering works from the field of management. Nonetheless, to ensure broader coverage, two sources of grey literature were also used, namely Google Scholar.com and ResearchGate.net. During the literature collection process, we applied the following searching criteria: “innovation” AND “ecosystem*” AND “review” in the title, “innovation” AND “ecosystem*” in the title and “review” in the keywords, “ecosystem*” AND “review” in the title, “ecosystem*” in the title and “review” in the keywords. Our initial literature search identified 10 literature reviews published between 2013 and 2019, including 6 reviews specifically focused on innovation ecosystems (Table 2).

We used these prior reviews as our starting point. Next, for more granularity, we examined individual papers analysed in the identified literature reviews, and ran our own review process in order to supplement the literature database with original and as yet unprocessed findings on different types, forms or variations of IE.

3.2 Thematic analysis and aggregation

To grasp the comprehensive scope of the theoretical and conceptual aspects of innovation ecosystems, we examined the findings from both literature reviews on innovation ecosystems (the upper part of Table 2) as well as the latest literature reviews on ecosystems, as the latter might reveal the distinguishing features of IE and justify their importance in comparison to other types (the lower part of Table 2). Next, we ran a thematic analysis in view of identifying themes within the data (Braun and Clarke 2006; Dabić et al. 2020). By theme, we mean the type, characteristic or criterion for typology used in prior literature reviews or individual articles. Characteristics help in grouping innovation ecosystems by similarity or relatedness, whereas types are labels used to refer to a set of similar innovation ecosystems. We therefore use a semantic level of analysis, that is we do not look for meanings that prior literature has not explicitly referred to. In line with the systematic approach to reviewing (Pellegrini et al. 2020), we performed our thematic analysis and aggregation without subjectively pre-determined differentiation criteria or innovation ecosystem types.

The literature analysis was run independently by two researchers, and the results were discussed in turn in view of extracting triangulated and congruent types of innovation ecosystems, as well as typology criteria. We also triangulated the typology criteria and changed the subsequent type lists, as well as agreed the final proposition by consensus.

4 The typology of innovation ecosystems

Interestingly, no previous literature review, be it focused on innovation ecosystems or on ecosystems in general, was specifically aimed at developing a typology of innovation ecosystems. Moreover, the need for granularity, segmentation and innovation ecosystem differentiation has been pointed out as a relevant research gap. For instance, the lack of research on the characteristics of innovation ecosystems (Gomes et al. 2018; Su et al. 2018), the lack of research on the distinguishing features of innovation ecosystems (Oh et al. 2016; Scaringella and Radziwon 2018; Valkokari 2015), or methodological shortcomings in conceptual papers resulting in a selective and too narrow approach to theoretical considerations (Aarikka-Stenroos and Ritala 2017; Dattee et al. 2018; Oh et al. 2016; Ritala and Almpanopoulou 2017). Furthermore, as shown by Oh et al. (2016), even though there are many blurry, fragmentarily recognized and proven aspects related to innovation ecosystems, these are complex phenomena that take many different forms in business practice. To the best of our knowledge, these forms, their characteristics and ways of aggregation have not as yet been addressed.

So far, studies that have considered types of innovation ecosystems have done it selectively and in isolation from the broader framework or previous recommendations. As a result, while various innovation ecosystems can be identified, this diversity does not meet the requirements of a logical division of theoretical constructs, and consequently does not help in cumulative knowledge creation. In particular, existing considerations on IE types are not comprehensive as only single characteristics were considered, while others were overlooked. Even complementary types to those under investigation are missing (e.g. addressing profitable IE while omitting unprofitable ones, addressing ego-centric IE while omitting eco-centric ones, or addressing intentional/deliberate/planned IE while omitting emergent/implicit ones). Furthermore, the prior literature does not offer sets of differentiation criteria or typology.

4.1 Innovation ecosystem types

Our literature analysis reveals 34 different types of innovation ecosystems (see Table 3): intentional (deliberate, planned), emergent (implicit), orchestrated (hierarchy), collectively coordinated (heterarchy), emerging, developmental, mature, declining, death, corporate-dominated, university dominated, meta-organizational, centralized, decentralized, ego-centric (firm-centric; hub-based), microscopic, middlescopic, macroscopic, focused on radical innovation, focused on incremental innovation, focused on path-breaking innovations, high-tech, multi-platform, city-based/innovation districts, local, regional, national, international, global, digital (clicks only), successful (strong), promising, profitable and sustainable.

By logical extension of the innovation ecosystem types identified, we revealed several complementary types: self-coordinated, symmetrical, asymmetrical, eco-centric, focused on disruptive innovation, focused on social innovation, medium-tech, low-tech, mono-platform, bricks & clicks, unsuccessful (weak), unprofitable and unsustainable. Moreover, as innovation ecosystems are understood as operating around the co-innovation process, we decided to distinguish six other types dependent on the extent to which innovation co-creation relationships are exploited through innovation processes implemented by IE actors, and focused on: (1) co-discovery; (2) co-development; (3) co-deployment; (4) co-delivery; (5) co-dissemination; and (6) multi-stage co-innovation.

4.2 Innovation ecosystem typology criteria

All in all, we distinguish 50 types of innovation ecosystems (shown in Table 3), using fourteen typological criteria aggregated into five more general categories: (1) life cycle, (2) structure, (3) innovation focus within IE, (4) scope and (5) performance.

The first criterion focuses on how the innovation ecosystem comes into existence, and in what life-cycle phase it can be found. In this context, IE can be divided according to their origin (intentional versus emergent IE, as inspired especially by the works of Planko et al. 2017; Rabelo and Bernus 2015; and Russell and Smorodinskaya 2018), or the stage of the ecosystem life cycle (emerging, developmental, mature, declining or death, as inspired especially by the works of Dedehayir et al. 2016; Moore 1993; Ritala et al. 2013).

The second criterion adopts a structural perspective, suggested as useful for conceptualizations in the ecosystem approach (Adner 2017). Following the structural view narrowed down to the actors’ perspective, innovation ecosystems can be divided into symmetrical and asymmetrical, or centralized and decentralized. However, if the focus is on innovation co-creation relationships, it is possible to distinguish ego- and eco-centric innovation ecosystems (as inspired by the findings from the literature review—Gomes et al. (2018). This also includes governance mechanisms (orchestration/hierarchy, collective coordination/heterarchy or self-coordination, as inspired especially by the works of Oh et al. 2016; Rabelo and Bernus 2015; and Russell and Smorodinskaya 2018).

The third criterion addresses the main aim of innovation ecosystems or its leading innovation focus. In a more detailed perspective, IEs can be categorized using three typological criteria: (1) the scope of innovation adopted within the ecosystem, that is microscopic, middlescopic or macroscopic, as suggested by Su et al. (2018); (2) the innovation type usually targeted by the actors of IE (i.e. focused especially on disruptive innovations, radical innovations, incremental innovations, social innovations or path-breaking innovations (Aarikka-Stenroos and Ritala 2017; Adner and Kapoor 2016; Walrave et al. 2018); and (3) the intensity of cooperation across the co-innovation process, that is innovation processes taking benefits only from co-discovery, only from co-development, only from co-deployment, only from co-delivery, only from dissemination, or benefiting from cooperation in a few or all stages of the innovation process (Autio and Thomas 2014; Klimas 2019; Song 2016).

The fourth typology criterion refers to the scope of innovation ecosystem activity, be it technological, spatial or physical. In terms of the technological scope, this is claimed to differentiate innovation ecosystems based on either the classification of the underlying industry using OECD recommendations, i.e. high-tech, medium-tech and low-tech innovation ecosystems (Ritala et al. 2013; Rocha et al. 2019), or the number of underlying technology platforms, i.e. mono- versus multi-platform innovation ecosystems (Gomes et al. 2018; Su et al. 2018; Vasconcelos Gomes et al. 2018). This is because IE can operate across one industry-wide platform or several company-specific platforms (Gawer and Cusumano 2014). Regarding the spatial scope, understood as the geographical range of both the activity and outputs of innovation ecosystems, it is possible to distinguish city-based/district-limited, local, regional, national, international and global innovation ecosystems (Mazzucato and Robinson 2018; Oh et al. 2016; Pombo-Juárez et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2018). The differences in geographical scope imply additional variations in terms of the level of horizontal, vertical, time-related and inter-systemic coordination within innovation ecosystems (Pombo-Juárez et al. 2017). Finally, regarding the physical scope, innovation ecosystems can be divided into those operating only in cyberspace (i.e. digital innovation ecosystems) and those operating in both the virtual and the real world, commonly known as bricks & clicks (Gomes et al. 2018; Rocha et al. 2019). In both cases, innovation ecosystems are shown as leveraging the dynamics of digital entrepreneurship (Beliaeva et al. 2019).

The last typology criterion addresses the performance of innovation ecosystems. Considering the type of performance, it is possible to differentiate innovation ecosystems based on the level of (1) innovation performance, i.e. successful/strong, unsuccessful/weak and promising (Mercan and Göktaş 2016; Sun et al. 2017; Xu et al. 2018); (2) economic performance reflected as profitable/healthy versus unprofitable/unhealthy innovation ecosystems (Autio and Thomas 2014); and (3) strategic performance, i.e. sustainable versus unsustainable innovation ecosystems (Wu et al. 2018).

In summarising considerations about the differentiation of innovation ecosystems, it is important to underline that the types identified within each criterion are not alternatives. On the contrary, it is possible and useful to categorize a given innovation ecosystem using several criteria at the same time. For instance, a given innovation ecosystem can be explored as ego-centric when considering innovation co-creation relationships, as centralized when considering the strategic dominance of a single actor, as deliberate when discussing the emergence of the innovation ecosystem, or as regional when considering the spatial scope. Therefore, we recommend adopting all categories of typology criteria as well as their specific types as this allows the researcher, practitioner or policymaker to form a vivid and comprehensive picture of the considered innovation ecosystem.

5 Conclusions

Our study addresses the conceptual challenge of a definition for the innovation ecosystem by offering a synthesis of delineation efforts and developing a useful typology within these frames. A recent study offers a consensual definition of innovation ecosystems by identifying three critical components, that is actors, relationships and artifacts (Granstrand and Holgersson 2020). We follow the same consensual perspective and systematically study the literature collected in view of identifying typology criteria and corresponding innovation ecosystem types. Thus, we map the intellectual structure of research, categorize the diversity of innovation ecosystems studied so far, identify types missing from the literature and offer a coherent typology of 50 innovation ecosystems across 5 key criteria.

Our study advances knowledge about innovation ecosystems in several ways. Firstly, we extend and complement recent efforts aimed at increasing the conceptual rigour and clarity of innovation ecosystems research. It is equally important to delineate such concepts from others and to identify attributes relevant for capturing the variety of phenomena at hand (Nag et al. 2007; Venkatraman 1989). Typologies help systematize this diversity by grouping according to certain attributes or criteria. They are acknowledged as the next step along the operationalization path for any conceptual constructs, and are the step made between definition and measurement (Ahlquist and Breunig 2012). While recent studies focus on delineating the concept by defining and identifying features that differentiate innovation ecosystems from other concepts, we tackle the diversity issue and systematize innovation ecosystems using a typical categorization-based approach. We identify 14 criteria used in prior literature, and through thematic analysis aggregate them into just 5, useful for identifying research gaps, helpful in focusing further empirical work, and crucial for the systematic accumulation of knowledge on innovation ecosystems. Secondly, by applying the typology to existing literature, we identify 16 innovation ecosystem types that have as yet received no research attention. Therefore, we advance research by rigorously identifying a comprehensive set of innovation ecosystems, and at the same time substantiating a research gap in extant literature. Thirdly, we contribute to recent streams of thought that acknowledge innovation ecosystems as complex and multidimensional (Vasconcelos Gomes et al. 2018; Bacon et al. 2020; Wei et al. 2020). At the same time, our typology helps locate relevant attributes that characterize a particular ecosystem.

We are aware of limitations that help outline promising directions for further research. Firstly, our study follows the fundamental assumption that a consensual typology is needed. Therefore, we used the available literature and are similarly skewed towards high–technology industries at the national level and from the perspective of focal firms (Lechman 2017). We suggest carrying out further research in other contexts such as medium- and low-tech industries instead of high-tech ones (Kapoor and Furr 2015; Oh et al. 2016; Song 2016), global markets instead of national ones (Arora et al. 2019; Yaghmaie and Vanhaverbeke 2019), and eco-centric innovation ecosystems instead of firm-centric ones (Holgersson et al. 2018; Jucevicius et al. 2016; Song 2016; Yaghmaie and Vanhaverbeke 2019).

Furthermore, our typology was developed using a cumulative approach as it builds on prior studies. While we were able to add 16 complementary types of innovation ecosystems and aggregate typology criteria, we are equally bound by prior literature foci. Other criteria may be developed, and we see qualitative in-depth studies as a particularly promising perspective for identifying such criteria. In the same vein, we believe that taxonomies may be developed as a bottom-up complementary procedure to our top-down typology. Therefore, we consider it worthwhile undertaking empirical research targeting the recognition of additional attributes that significantly differentiate innovation ecosystems.

Notes

See the differences in the scope and meaning of open innovation, collaborative innovation and co-innovation (Lee et al. 2012).

References

Aarikka-Stenroos L, Ritala P (2017) Network management in the era of ecosystems: systematic review and management framework. Ind Mark Manage 67:23–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.08.010

Adner R (2006) Match your innovation strategy to your innovation ecosystem. Harv Bus Rev 84(4):98–107

Adner R (2017) Ecosystem as structure: an actionable construct for strategy. J Manag 43:39–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316678451

Adner R, Kapoor R (2016) Innovation ecosystems and the pace of substitution: re-examining technology S-curves. Strateg Manag J 37:625–648. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2363

Ahlquist JS, Breunig C (2012) Model-based clustering and typologies in the social sciences. Political Anal 20:92–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpr039

Arena M, Azzone G, Piantoni G (2018) System building for resilient innovation ecosystems. Stockholm.

Arora A, Belenzon S, Patacconi A (2019) A theory of the US innovation ecosystem: evolution and the social value of diversity. Ind Corp Change 28:289–307. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dty067

Autio E, Thomas LDW (2014) Innovation ecosystems: implications for innovation management. In: Dodgson M, Philips N, Gann DM (eds) The Oxford handbook of innovation management. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 204–288

Bacon E, Williams MD, Davies G (2020) Coopetition in innovation ecosystems: a comparative analysis of knowledge transfer configurations. J Bus Res 115:307–316

Beliaeva T, Ferasso M, Kraus S, Damke EJ (2019) Dynamics of digital entrepreneurship and the innovation ecosystem: a multilevel perspective. Int J Entrep Behav Res 26:266–284. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-06-2019-0397

Bouncken RB, Fredrich V (2016) Business model innovation in alliances: successful configurations. J Bus Res 69:3584–3590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.01.004

Bouncken RB, Fredrich V, Ritala P, Kraus S (2018) Coopetition in new product development alliances: advantages and tensions for incremental and radical innovation. Br J Manag 29:391–410. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12213

Bouncken RB, Pesch R, Kraus S (2015) SME innovativeness in buyer–seller alliances: effects of entry timing strategies and inter-organizational learning. RMS 9:361–384. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-014-0160-6

Braun V, Clarke V (2006) Using thematic analysis in psychology. Appl Qual Res Psychol 3:77–101. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-35913-1

Carayannis EG, Campbell DFJ (2009) “Mode 3’and’Quadruple Helix”: toward a 21st century fractal innovation ecosystem. Int J Technol Manag 46:201–234

Clarysse B, Wright M, Bruneel J, Mahajan A (2014) Creating value in ecosystems: crossing the chasm between knowledge and business ecosystems. Res Policy 43:1164–1176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.04.014

Czakon W, Czernek-Marszałek K (2020) Competitor Perceptions in Tourism Coopetition. J Travel Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287519896011

Czakon W, Klimas P, Mariani M (2020) Behavioral antecedents of coopetition: a synthesis and measurement scale. Long Range Plan. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2019.03.001

Dabić M, Vlačić B, Paul J, Dana LP, Sahasranamam S, Glinka B (2020) Immigrant entrepreneurship: a review and research agenda. J Bus Res 113:25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.013

Dattee B, Alexy O, Autio E (2018) Maneuvering in poor visibility: how firms play the ecosystem game when uncertainty is high. Acad Manag J 61:466–498

de Vasconcelos Gomes LA, Salerno MS, Phaal R, Probert DR (2018) How entrepreneurs manage collective uncertainties in innovation ecosystems. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 128:164–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.11.016

Dedehayir O, Mäkinen SJ, Roland OJ (2016) Roles during innovation ecosystem genesis: a literature review. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:18–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.028

Durst S, Poutanen P (2013) Success factors of innovation ecosystems - Initial insights from a literature review. In: CO-CREATE 2013: the boundary-crossing conference on co-design in innovation, pp 27–38

Dyer JH, Singh H (1998) The relational view: Cooperative strategy and sources of interorganizational competitive advantage. Acad Manag Rev 23(4):660–679

Ferasso M, Takahashi ARW, Gimenez FAP (2018) Innovation ecosystems: a meta-synthesis ecosystems. Int J Innov Sci. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-07-2017-0059

Ferreira JJ, Fernandes CI, Kraus S (2019) Entrepreneurship research: mapping intellectual structures and research trends. Rev Manag Sci 13:181–205

Gawer A, Cusumano MA (2014) Industry platforms and ecosystem innovation. J Prod Innov Manag 31(3):417–433

Glińska-Neweś A, Escher I, Brzustewicz P, Szostek D, Petrykowska J (2018) Relationship-focused or deal-focused? Building interpersonal bonds within B2B relationships. Balt J Manag 13:508–527. https://doi.org/10.1108/BJM-02-2017-0038

Gomes LADV, Facin ALF, Salerno MS, Ikenami RK (2018) Unpacking the innovation ecosystem construct: Evolution, gaps and trends. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:30–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.009

Granstrand O, Holgersson M (2020) Innovation ecosystems: a conceptual review and a new definition. Technovation. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2019.102098

Holgersson M, Granstrand O, Bogers M (2018) The evolution of intellectual property strategy in innovation ecosystems: uncovering complementary and substitute appropriability regimes. Long Range Plan 51:303–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.08.007

Iyer B, Davenport TH (2008) Reverse engineering Google’s innovation machine. Harv Bus Rev 86:1–12

Jucevičius G, Grumadaitė K (2014) Smart development of innovation ecosystem. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 156:125–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.133

Jucevicius G, Juceviciene R, Gaidelys V, Kalman A (2016) The emerging innovation ecosystems and “valley of death”: towards the combination of entrepreneurial and institutional approaches. Inzinerine Ekonomika Eng Econ 27:430–438. https://doi.org/10.5755/j01.ee.27.4.14403

Kang Q, Li H, Cheng Y, Kraus S (2019) Entrepreneurial ecosystems: analysing the status quo. Knowl Manag Res Pract. https://doi.org/10.1080/14778238.2019.1701964

Kapoor R, Lee JM (2013) Coordinating and competing in ecosystems: How organizational forms shape new technology investments. Strateg Manag J 34(3):274–296

Kapoor R, Furr NR (2015) Complementaries and competition: unpacking the drivers of entrants’ technology choices in the solar photovoltaic industry. Strateg Manag J 36:416–436. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj

King WR, He J (2005) Understanding the role and methods of meta-analysis in IS research. Commun Assoc Inf Syst 16:665–668. https://doi.org/10.17705/1cais.01632

Klimas P (2019) Relacje współtworzenia innowacji w ekosystemach. Kontekst ekosystemu gamingowego. C.H. Beck, Warsaw

Kraus S, Breier M, Dasí-Rodríguez S (2020a) The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. Int Entrep Manag J 16:1023–1042

Kraus S, Kailer N, Dorfe J, Jones P (2020b) Open innovation in (young) SMEs. Int J Entrep Innov 21:47–59

Lechman E (2017) The diffusion of information and communication technologies. Routledge, London

Lee SM, Olson DL, Trimi S (2012) Co-innovation : convergenomics, collaboration, and co-creation for organizational values. Manag Decis 50:817–831. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251741211227528

Liguori E, Bendickson J, Solomon S, McDowell WC (2019) Development of a multi-dimensional measure for assessing entrepreneurial ecosystems. Entrep Reg Dev 31:7–21

Luo J (2018) Architecture and evolvability of innovation ecosystems. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:132–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.06.033

Maitlis S, Christianson M (2014) Sensemaking in organizations: taking stock and moving forward. Acad Manag Ann 8:57–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2014.873177

Mazzucato M, Robinson DKR (2018) Co-creating and directing innovation ecosystems? NASA’s changing approach to public-private partnerships in low-earth orbit. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:166–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.03.034

Mercan B, Göktaş D (2016) Components of innovation ecosystems: a cross-country study components of innovation ecosystems: a cross-country study. Int Res J Finance Econ 76:102–112

Moore JF (1993) Predators and prey: a new ecology of competition. Harv Bus Rev 71:75–86

Nag R, Hambrick DC, Chen MJ (2007) What is strategic maanagement, really? Inductive derivation of a consensus definition of the field. Strateg Manag J 28:935–955. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj

Oh DS, Phillips F, Park S, Lee E (2016) Innovation ecosystems: a critical examination. Technovation 54:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2016.02.004

Pellegrini MM, Ciampi F, Marzi G, Orlando B (2020) The relationship between knowledge management and leadership: mapping the field and providing future research avenues. J Knowl Manag 24:1445–1492. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-01-2020-0034

Pellikka J, Ali-Vehmas T (2018) Managing Innovation Ecosystems to Create and Capture Value in ICT Industries. Technol Innov Manag Rev 6:17–24. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/1024

Phillips MA, Srai JS (2018) Exploring emerging ecosystem boundaries: defining ‘the game’. Int J Innov Manag 22(08):1840012

Pilinkiene V, Maciulis P (2014) Comparison of different ecosystem analogies: the main economic determinants and levels of impact. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 156:365–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.11.204

Planko J, Chappin MMH, Cramer JM, Hekkert MP (2017) Managing strategic system-building networks in emerging business fields: a case study of the Dutch smart grid sector. Ind Mark Manag 67:37–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2017.06.010

Pombo-Juárez L, Könnölä T, Miles I, Saritas O, Schartinger D, Giesecke S (2017) Technological forecasting & social change wiring up multiple layers of innovation ecosystems: contemplations from personal health systems foresight. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 115:278–288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.04.018

Rabelo RJ, Bernus P (2015) A holistic model of building innovation ecosystems. IFAC-PapersOnLine 28:2250–2257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ifacol.2015.06.423

Radziwon A (2018) Managing inter-organizational collaboration of SMEs in a regional ecosystem. In: ISPIM Conference 2018

Reynolds EB, Uygun Y (2018) Strengthening advanced manufacturing innovation ecosystems: the case of Massachusetts. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:178–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.06.003

Ritala P, Agouridas V, Assimakopoulos D, Gies O (2013) Value creation and capture mechanisms in innovation ecosystems: a comparative case study. Int J Technol Manag 63:244. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijtm.2013.056900

Ritala P, Almpanopoulou A (2017) In defense of ‘eco’ in innovation ecosystem. Technovation 60–61:39–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2017.01.004

Ritala P, Kraus S, Bouncken RB (2016) Introduction to coopetition and innovation: contemporary topics and future research opportunities. Int J Technol Manage 71:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJTM.2016.077985

Rocha CF, Mamédio DF, Quandt CO (2019) Startups and the innovation ecosystem in Industry 4.0. Technol Anal Strateg Manag 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09537325.2019.1628938

Rohrbeck R, Hölzle K, Gemünden HG (2009) Opening up for competitive advantage—how Deutsche Telekom creates an open innovation ecosystem. R&D Manag 39:420–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9310.2009.00568.x

Roth S, Clark C, Trofimov N, Mkrtichyan A, Heidingsfelder M, Appignanesi L, Kaivo-oja J (2017) Futures of a distributed memory. A global brain wave measurement (1800–2000). Technol Forecast Soc Chang 118:307–323. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.02.031

Rubens N, Still K, Huhtamaki J, Russell MG (2011) A network analysis of investment firms as resource routers in Chinese innovation ecosystem. J Softw 6:1737–1745. https://doi.org/10.4304/jsw.6.9.1737-1745

Russell MG, Smorodinskaya NV (2018) Leveraging complexity for ecosystemic innovation. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:114–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.11.024

Scaringella L, Radziwon A (2018) Innovation, entrepreneurial, knowledge, and business ecosystems: old wine in new bottles ? Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:59–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.09.023

Schroth F, Häußermann JJ, Schraudner M (2018) Strategies for cooperation between companies and research organisations in innovation ecosystems—a case study of the German microelectronics and photonics industries. In: ISPIM innovation symposium, (June), 1–13.

Shaw DR, Allen T (2018) Studying innovation ecosystems using ecology theory. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:88–102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.11.030

Song J (2016) Innovation ecosystem: impact of interactive patterns, member location and member heterogeneity on cooperative innovation performance. Innovation 18:13–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14479338.2016.1165624

Spelmeyer M, Lingens B (2018) How young entrepreneurial companies orchestrate business ecosystems Bernhard Lingens. In: Proceedings of the XXIX ISPIM innovation conference

Su YS, Zheng ZX, Chen J (2018) A multi-platform collaboration innovation ecosystem: the case of China. Manag Decis 56:125–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-04-2017-0386

Sun SL, Chen VZ Sunny SA, Chen J (2017) Venture capital as an ecosystem engineer for regional innovation in an emerging market. In: 2017 IEEE technology and engineering management society conference, TEMSCON 2017, (January), 13–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1109/TEMSCON.2017.7998347

Talmar M, Walrave B, Podoynitsyna KS, Holmström J, Romme AGL (2018) Mapping, analyzing and designing innovation ecosystems: the ecosystem pie model. Long Range Plan. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2018.09.002

Teece DJ (2007) Explicating dynamic capabilities: the nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strateg Manag J 28:1319–1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj

Thomas LDW, Autio E, Gann DM (2014) Architectural Leverage: Putting Platforms in Context. Acad Manag Perspect 28(2):198–219. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2011.0105

Tsujimoto M, Kajikawa Y, Tomita J, Matsumoto Y (2018) A review of the ecosystem concept—towards coherent ecosystem design. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.06.032

Valkokari K (2015) Business, innovation, and knowledge ecosystems: how they differ and how to survive and thrive within them. Technol Innov Manag Rev 5:17–24. https://doi.org/10.22215/timreview/919

Vargo SL (2009) Toward a transcending conceptualization of relationship: a service-dominant logic perspective. J Bus Ind Mark 24:373–379. https://doi.org/10.1108/08858620910966255

Venkatraman N (1989) Strategic orientation of business enterprises: the construct, dimensionality, and measurement. Manage Sci 35:942–962

Walrave B, Talmar M, Podoynitsyna KS, Romme AGL, Verbong GPJ (2018) A multi-level perspective on innovation ecosystems for path-breaking innovation. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:103–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.04.011

Wei F, Feng N, Yang S, Zhao Q (2020) A conceptual framework of two-stage partner selection in platform-based innovation ecosystems for servitization. J Clean Prod 121431

Wu J, Ye R, Ding L, Lu C, Euwema M (2018) From “transplant with the soil” toward the establishment of the innovation ecosystem: a case study of a leading high-tech company in China. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:222–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.06.001

Xu G, Wu Y, Minshall T, Zhou Y (2018) Exploring innovation ecosystems across science, technology, and business: a case of 3D printing in China. Technol Forecast Soc Chang 136:208–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2017.06.030

Yaghmaie P, Vanhaverbeke W (2019) Identifying and describing constituents of innovation ecosystems: a systematic review of the literature. EuroMed J Bus 1–32.https://doi.org/10.1108/EMJB-03-2019-0042

Zakrzewska-Bielawska A (2019) Recognition of relational strategy content: insight from the managers’ view. Eurasian Bus Rev 9:193–211

Acknowledgments

We thank the Editors and Reviewers from Review of Managerial Science for their insightful and constructive comments improving the manuscript.

Funding

This paper was supported by a research grant from the National Science Centre under the project titled: Co-creative relationships and innovativeness—the perspective of the video game industry (UMO-2013/11/D/HS4/04045). Moreover, publication was supported by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in Poland under the programme "Regional Initiative of Excellence" 2019–2022 project number 015/RID/2018/19 total funding amount 10 721 040,00 PLN".

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Declaration of the exclusivity of submission

The manuscript has not been published previously, it is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, and if accepted, it will not be published elsewhere in the same form, in English or any other language.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Klimas, P., Czakon, W. Species in the wild: a typology of innovation ecosystems. Rev Manag Sci 16, 249–282 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-020-00439-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-020-00439-4