Abstract

Entrepreneurial teams are dynamic entities that frequently experience the exit of individual team members. Such entrepreneurial team member exits (ETMEs) entail serious consequences for the exiting individual, the remaining team, and the performance of the affected venture. While ETMEs are receiving increasing scholarly attention, the research landscape is still considerably fragmented. This is the first article to take stock, analyze, and discuss this crucial and emerging field of research by providing a systematic review of the literature on ETMEs. We identify central themes comprising of antecedents, routes, consequences, and the contextual embeddedness of ETMEs and integrate them into a comprehensive processual framework. Based on this framework, we contribute to the research on ETMEs by discussing the themes in the light of promising theoretical perspectives, introducing novel ideas, concepts, and approaches to enrich future avenues. Specifically, we propose to expand the concept of team heterogeneity to advance our understanding of antecedents as well as to investigate power relations and negotiation behavior within ETME routes. In addition, we offer ways to resolve the sometimes inconsistent findings in terms of venture consequences and present a fertile approach for a more in-depth cultural contextualization of the phenomenon.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Past research has demonstrated that ventures led by teams outperform solo-ventures in terms of growth and profitability (Cooper and Bruno 1977; Lechler 2001). Thus, research on entrepreneurial teams, defined as “two or more individuals who have a significant financial interest and participate actively in the development of the enterprise” (Cooney 2005, p. 229), has flourished in the last two decades (Klotz et al. 2014; Lazar et al. 2019). Recently, the dynamic nature of entrepreneurial team composition has gained significant interest in the studies of entrepreneurial teams (Ucbasaran et al. 2003; Guenther et al. 2015; Le et al. 2017; Nikiforou et al. 2018). Entrepreneurial teams change over time, and a large number of entrepreneurial teams are affected by the departure of one or more team members. Empirical studies have shown that up to 40% of entrepreneurial teams experience at least one exit of a team member (Hellerstedt et al. 2007; Hellerstedt 2009; Grilli 2011; Le et al. 2017). Such entrepreneurial team member exits (hereafter ETMEs), describe the process in which a member of an entrepreneurial team leaves the team, while the remaining team member(s) continue(s) to develop the (prospective) company. As such, ETMEs are considered a sub-set of entrepreneurial exits (Ucbasaran et al. 2003; Breugst et al. 2015; Piva and Rossi-Lamastra 2017).

Such ETMEs are described to have serious personal consequences for the departing individual (Breugst et al. 2015) and for the composition of the remaining team (Vanaelst et al. 2006; Loane et al. 2007; Goi and Kokuryo 2016; Yoon 2018) as well as for the performance of the affected ventures (Chandler et al. 2005; Bamford et al. 2006; Le et al. 2017). Hence, obtaining systematic knowledge about the exit of individual team members of entrepreneurial teams is fundamental for a deeper understanding of how team-based ventures function, change over time, and perform.

Research on exits of team members in entrepreneurial teams is marked by considerable fragmentation. Knowledge is scattered among numerous articles of the entrepreneurship and management literature that each take different perspectives on the antecedents of ETMEs (Fiet et al. 1997; Forbes et al. 2006; Hellerstedt et al. 2007; Cardon et al. 2017) and often only provide implicit information on exit routes (Forbes et al. 2006; Goi and Kokuryo 2016). Moreover, empirical studies yield contradictory findings concerning the effects of ETMEs on venture performance (Guenther et al. 2015). While some articles point towards positive consequences such as higher profitability of the enterprise (Chandler et al. 2005), others demonstrate lower survival rates of the affected young firm (Le et al. 2017). Thus, research on ETMEs lacks a comprehensive overview that makes the existing knowledge available for researchers and acts as a starting point for more systematic research. This, in turn, would enhance our practical and theoretical understanding of the phenomenon (Wennberg and DeTienne 2014; Piva and Rossi-Lamastra 2017).

The purpose of this article is to take stock of past scholarly work and to provide a compilation of central themes of ETMEs to stimulate discussion and encourage further research. To achieve this, we employ a systematic approach to review the literature on ETMEs (Tranfield et al. 2003). We adopt a qualitative analysis that permits a comprehensive description and in-depth interpretation of the analyzed articles (Bouncken et al. 2015; Nikiforou et al. 2018; Pret and Cogan 2018).

This is the first article to analyze, map, and discuss the current body of work on ETMEs by providing a systematic literature review. We derive a processual framework of ETMEs based on the themes of antecedents, routes, consequences and contextual embeddedness. After the presentation of the contemporary results within these themes, we discuss current research challenges and provide novel perspectives and approaches to move the field forward. As such, this article contributes to research on the dynamics of entrepreneurial teams as well as entrepreneurial exits.

2 Foundations

2.1 Conceptual boundaries

This section aims to provide a definition and overview of research on entrepreneurial teams as well as a conceptualization of ETMEs, which together constitute the conceptual boundaries for the systematic literature review.

2.1.1 Entrepreneurial teams

In the past two decades, the notion of the lone entrepreneur characterized by distinct traits has been challenged increasingly by the mounting emphasis of scholars on the importance of entrepreneurial teams in the entrepreneurial process (Cooney 2005; Harper 2008; Schjoedt and Kraus 2009; Schjoedt et al. 2013; Ben-Hafaïedh and Cooney 2017). Teams decisively influence the course of development of the venture, particularly in young firms and are often framed as the most defining factor for entrepreneurial ventures (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1990; Eisenhardt 2013).

The composition of entrepreneurial teams, as well as its impact on venture performance, has been the focus of several studies in this field of research (Ensley and Hmieleski 2005; Visintin and Pittino 2014; Zhou et al. 2015; Thiess et al. 2016). Team composition characteristics such as human capital, social networks, or prior shared experience, is strongly reflected in the success of the entrepreneurial venture (Jin et al. 2017). Additional research has been conducted in areas of team processes such as interpersonal conflicts, goal setting and planning within entrepreneurial teams, or collective cognition and team cohesion (Klotz et al. 2014).

Despite the rise in research and the multitude of significant findings, defining entrepreneurial teams is not an easy task. There is no consensual use of a standardized definition for entrepreneurial teams among scholars (e.g., Kamm et al. 1990; Ensley et al. 1998; Cooney 2005; Harper 2008). Definitions range from meticulous and sophisticated variants, which try to incorporate as many distinctive attributes as possible (e.g., Schjoedt and Kraus 2009), to definitions allowing room for interpretation (e.g., Harper 2008). Some authors define entrepreneurial teams as two or more individuals in a jointly established firm with a financial interest (Kamm et al. 1990; Cooney 2005). Others focus on the team members involvement in decision-making processes (Gartner et al. 1994; Klotz et al. 2014), the team members influence on the strategy of the new venture (Ensley et al. 1998) or the formal position of the team members (Eisenhardt and Schoonhoven 1990). In addition to the numerous definitions that offer different perspectives, the extensive terminology provides challenges for research. In addition to entrepreneurial teams, literature refers to new top management teams, new venture teams, start-up teams, family teams, or founding teams (Ensley and Hmieleski 2005; Wu et al. 2009; Hauser et al. 2012; Zhou et al. 2015).

To outline the conceptual boundaries of entrepreneurial teams, we strive for a definition, which offers a common ground for the different terms and definitions used in contemporary research on entrepreneurial teams and emphasize the dynamics of entrepreneurial team composition. We, therefore, follow the rationale of Cooney (2005, p. 229), stating that an entrepreneurial team consists of “two or more individuals who have a significant financial interest and participate actively in the development of the enterprise”. Further, Cooney (2005) explicitly acknowledges that ‘development of the enterprise’ refers to the dynamic nature of the entrepreneurial teams where members can leave or join along the venture development process making it the ideal foundation to advance research on ETMEs. In this view, entrepreneurial teams are fluid entities with an evolutionary character. Not only are they flexible concerning team size but also in terms of the time and way members join and leave the team.

2.1.2 Entrepreneurial team member exit

Entrepreneurial teams are dynamic and frequently experience exits of individual team members (Ucbasaran et al. 2003; Hellerstedt et al. 2007; Grilli 2011). We consider ETMEs as a subset of entrepreneurial exits, which are defined as the process by which the founders of privately held firms leave the firm they helped to create (DeTienne 2010; DeTienne and Cardon 2012; Piva and Rossi-Lamastra 2017). Entrepreneurial exits can take various forms and are often related to firm exits where the entire firm is dissolved and leaves the market (DeTienne and Wennberg 2016). Our research, however, examines member exits from ongoing firms. In an ETME, one or more members of the entrepreneurial team leave their team and remove themselves (or are removed) from the primary ownership and decision-making structure of the venture (Breugst et al. 2015 referring to DeTienne 2010), while the team continues with the development of its firm (Ucbasaran et al. 2003; Loane et al. 2014). Accordingly, we conceptualize ETMEs as the process in which a member of an entrepreneurial team leaves the team, while the remaining team member(s) continue(s) to develop the (prospective) company.

2.2 Review approach

This review applies a systematic approach, which is characterized by transparency and reproducibility to reduce subjectivity and bias in data collection (Tranfield et al. 2003). Thus, this review approach contributes to enforcing scientific rigor and limits the application of simple heuristics (Crossan and Apaydin 2010; Nabi et al. 2017) and has been used with great success in current literature reviews (Parastuty et al. 2015; de Mol et al. 2015; Bouncken et al. 2015; Sageder et al. 2018; Pret and Cogan 2018). The systematic review includes the specification of the research objective, conceptual boundaries, search boundaries, potential search terms, and covered period as well as the inclusion and exclusion criteria of the articles which were defined. The review approach is portrayed in Fig. 1.

We delineated the key concepts to narrow down the search and fit our research objectives. In this case, these conceptual boundaries consisted of the synthesis of the key terms “entrepreneurial teams” and “entrepreneurial exit”. The conceptual boundaries allowed us to derive search terms. Due to the proliferation of terminology regarding entrepreneurial teams (Schjoedt and Kraus 2009), a diverse set of search terms was required to cover the broad spectrum of team terms. Similar to entrepreneurial teams, there is a considerable number of expressions describing an exit of team members (e.g., withdrawal, leave, departure). We also checked for founder and owner exits and investigated if the contexts fit the conceptual boundaries. Search terms, therefore, were extensive.

For the search itself, we primarily scanned the Web of Science Core Collection supplemented by Business Source Premier via EBSCO Host. To guarantee a certain level of quality, we focused on peer-reviewed journal articles (Bouncken et al. 2015; Kraus et al. 2018). Additionally, we employed Google Scholar’s full text search and compared the findings to the previous search results to check if the rigidity of the previous search led to the exclusion of relevant peer-reviewed papers (Wang and Chugh 2014; de Mol et al. 2015). We refrained from specifying a definite starting date for the search. Articles prior to 1990 were not expected as this was the year when Kamm et al. (1990) published their seminal article theorizing entrepreneurial teams (Cooney 2005; Harper 2008; Schjoedt and Kraus 2009). All articles up to June 2019 were included, with this date marking the end of the coverage period.

The search strategy involved two researchers and a subsequent fusion of the search results. This increased search efforts due to the overlapping articles but offered an additional means of search validation. The initial extensive search yielded 1530 overlapping results. After the first screening of the titles, abstracts, and keywords, 133 articles were shortlisted for further investigation. These 133 articles were thoroughly checked, and further exclusion criteria were applied. In this step, articles that neither offered the context of new ventures or prestart-ups nor focused on teams were eliminated. We further excluded articles that did not fit into the conceptual boundaries (e.g., dissolution of the whole team, turnover of employees, project teams, temporary teams). After this process, we conducted backwards citation search checking the bibliographies of the articles as well as publication lists of prominently presented authors for further articles fitting the conceptual boundaries. The final sample consists of 50 articles for in-depth analysis. The number of articles is similar to and in some cases exceeds the sample sizes of other literature reviews of emerging topics and allows for a deeper engagement with each individual study (de Mol et al. 2015; Nikiforou et al. 2018; Pret and Cogan 2018; Kraus et al. 2018). Further, scholars advocate that the rigor of the search criteria and exclusion criteria in ensuring the relevance of the identified work is more important than the absolute number of sampled articles (Baldacchino et al. 2015).

2.3 Data analysis

Data coding followed inductive open coding approaches including the identification of first-order codes, second-order codes, and aggregate themes (Gioia et al. 2013; Nabi et al. 2017). We analyzed and coded the articles in a content-focused manner. This allowed us to incorporate articles whose main contributions do not lie in the area of ETMEs but that, nonetheless, contain significant information for the development of the topic. To reduce subjectivity in the coding procedure, two authors coded the articles manually and independently. Both authors inspected the coding of the respective other author, subsequently merging the codes together. Differences between the coders were discussed and findings were streamlined. Moreover, the coding structure was presented to and discussed with other researchers familiar with the topic. In sum, we identified 24 first-order codes that were then grouped into second-order codes. Another abstraction of codes led to aggregate themes (the data structure is provided in the appendix). An iterative back and forth between the sample and emerging themes, as well as related theories characterizes the coding approach (Nabi et al. 2017; Pret and Cogan 2018). The categorization was inspired by the work on process perspectives of entrepreneurial exit literature (Wennberg 2007; Wennberg et al. 2010; Wennberg and DeTienne 2014). The categories were subsequently linked in a process of ETMEs including the antecedents, routes, consequences, and contextual embeddedness shown in Fig. 2. This framework with its categories and subdivisions served as the foundation for the final classification of the reviewed articles (the classification of articles based on derived categories is provided in the appendix).

2.4 An overview of sampled articles

2.4.1 Publication rates and journal outlets

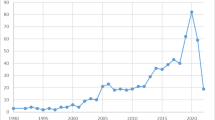

Research on ETMEs is still quite young but has experienced growing interest in recent years (Wennberg and DeTienne 2014; Guenther et al. 2015). The earliest two articles were published in 1993 followed by one article in 1997 and then in the year 2000. Since 2002 there has been a continuous stream of publications of at least one article per year in our sample, with a modest peak both in 2006 and 2015.

The 50 articles were published in 26 different journals. The Journal of Business Venturing and Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, which are among the top journals in entrepreneurship, have the highest count in terms of publications with nine and eight papers respectively. They are followed by the Academy of Management Journal with four publications and the International Small Business Journal with three articles. Other journal outlets add two or less publications to the final sample (see Table 1 for greater detail).

2.4.2 Methodological approaches and applied theories

Quantitative approaches dominate the sample by 58% and include different regression models (e.g., Grilli 2011; Junkunc and Eckhardt 2009) or event history analysis (e.g. Boeker and Karichalol 2002; Busenitz et al. 2004). In comparison, qualitative approaches are underrepresented and only used by 28% of the papers. All of these articles employed a case study approach with the exception of one article, which conducted six in-depth interviews and applied inductive theorizing (Forbes et al. 2006). Two studies utilized mixed-methods. Although both articles focused on qualitative methods in their analysis, the studies also incorporated quantitative measurements. The remaining 10% of the papers are conceptual or theoretical in nature.

In terms of geographical regions, most articles draw their samples from North America (USA, Canada) and European countries (Belgium, Italy, Germany, Norway, Sweden, or Ireland). Two articles focused on other regions (Honduras and Indonesia).

Researchers relied on a wide range of different theories to discuss ETMEs. Prominently used in top management team research, the upper echelon perspective has been conveyed into the context of EMTEs to explain how team changes impact venture performance (Vanaelst et al. 2006). Agency theory has been applied to examine the relationships among team members and external stakeholders (Rosenstein et al. 1993; Fiet et al. 1997; Junkunc and Eckhardt 2009). Furthermore, the articles investigated changes in the entrepreneurial teams’ capitals through the human capital lens (Ucbasaran et al. 2003; Forbes et al. 2006; Grilli 2011), a social capital perspective (Bamford et al. 2006), the resource-based view and the knowledge-based view (Hauser et al. 2012; Loane et al. 2014; Le et al. 2017).

3 Results

3.1 Antecedents

As Ronstadt (1986) proposed in his seminal work, only the investigation of the antecedents of the exit phenomenon will allow us to gain more profound knowledge about entrepreneurship. In line with research on entrepreneurial exit (e.g. DeTienne 2010; DeTienne and Cardon 2012; Dehlen et al. 2014), we refer to antecedents as the preceding events, reasons, causes, or conditions that lead to ETMEs. In this theme, we identified three categories—the individual level, the team level, and the organizational level.

On the individual level, research shows that a member of an entrepreneurial team may leave because of reasons similar to those of entrepreneurial exits in general (Ronstadt 1986; DeTienne 2010). First, a member might leave due to better prospects elsewhere (Loane et al. 2014). Leaving entrepreneurial team members pursue other opportunities, which can include internships, job offers, and studies at university (Bjørnåli and Gulbrandsen 2010; Goi and Kokuryo 2016). Second, lifestyle issues or family reasons can also be triggers to exit (Muske and Fitzgerald 2006; Loane et al. 2014; Goi and Kokuryo 2016). However, other team-specific characteristics in context of the teams such as the role within the team, and the team member’s skills are of paramount importance (Boeker and Karichalol 2002; Hellerstedt et al. 2007; Collewaert and Fassin 2013). For example, the exit of a team member can happen due to insufficient skills or the need for different skills, which the individual, in her or his own opinion, is unable to contribute to the team (Collewaert and Fassin 2013; Goi and Kokuryo 2016; D’hont et al. 2016).

In terms of the team level, different forms of heterogeneity have been studied and linked to team member exits. Here, the results can be categorized in a recent typology of different forms of heterogeneity. Referring to this, we identified heterogeneity as variety and heterogeneity as separation. Variety refers to the difference in composition of relevant knowledge and experience, and separation describes differences concerning attitudes and personal opinions (Harrison and Klein 2007).

Heterogeneity as variety, including education, functional expertise, industry experience (Chandler et al. 2005), entrepreneurial experience (Ucbasaran et al. 2003) as well as age and industry experience (Hellerstedt et al. 2007), is related to a higher amount of ETMEs. Conversely, functional diversity among team members (Boeker and Wiltbank 2005), and gender diversity decreases the number of ETMEs (Hellerstedt et al. 2007). Past research on heterogeneity as separation shows how diverging views and attitudes of team members are connected to their potential exits. Differing ambitions (Vanaelst et al. 2006), and a diverging understanding of fundamental issues such as how to conduct business and the strategic orientation (Discua Cruz et al. 2013; Loane et al. 2014) play a fundamental role in this regard.

These forms of heterogeneity can potentially lead to conflict among team members. Because of different perspectives and opinions resulting from different individual backgrounds, team members can experience alienation, anger, and conflicts that, in turn, peak in ETMEs (Ensley et al. 2002; Chandler et al. 2005). Articles, thus, tend to explain their results and heterogeneity measures through interpersonal relationships among constituents of the team. Under this lens, scholars found the importance of the concepts of friendship and trust (D’hont et al. 2016; Williams Middleton and Nowell 2018). Friendship matters in the context of entrepreneurial teams in a sense that lower levels of friendship might hinder team formation and facilitate ETMEs (Francis and Sandberg 2000). On the one hand, friendships among team members increase flexibility to modify work roles within the team. On the other hand, they complicate asking team members to leave the team if the circumstances require it (Zolin et al. 2011). With regards to trust, low intrateam trust resulted in conflict and low team cohesion that was subsequently associated with exits (Discua Cruz et al. 2013; Breugst et al. 2015).

In relation to drivers for ETMEs on an organizational level, several articles emphasize the influence of investors such as venture capitalists or business angels (Busenitz et al. 2004) and/or the advisory boards (Breugst et al. 2015). The influence of decision-making by investors can have a paramount impact on the composition of the entrepreneurial team (Busenitz et al. 2004; Lim et al. 2013). When venture capitalists join the firm, they have the possibility to enforce strategic change, which sometimes involves the change of the entrepreneurial team to meet their expectations (Hellmann and Puri 2002). The dismissal of the entrepreneurial team may occur due to different needs in the different stages of growth of a venture (Drazin and Kazanjian 1993). Furthermore, if members of the entrepreneurial teams are underperforming, dissenting, or acting unethically, investors are sometimes found to dismiss a team member (Beckman et al. 2007; Collewaert and Fassin 2013; Loane et al. 2014). The replacement of an entrepreneurial team member can also be a prerequisite for venture capitalists to invest in the company at all (Clarysse and Moray 2004). Thereby, the overall influence of outside equity is expected to be moderated by the ownership and their power within the enterprise. Higher levels of ownership and control by investors and by venture capitalists are positively associated with team exits (Fiet et al. 1997; Boeker and Karichalol 2002). The interpersonal relationship between the entrepreneurial teams and investors and how they interact further affects possible exits. Negotiation behaviors (especially positional bargaining) of investors in the pre-investment phase are strongly linked to higher team member dismissals in the post-investment phase (Erikson and Berg-Utby 2009). Additionally, tensions between the team of entrepreneurs and investors can arise, leading to more pronounced faultlines and relationship conflicts (Lim et al. 2013), as well as task and goal conflicts (Collewaert 2012), potentially causing exits in the long run. In this regard, scholars found that mutually fair treatment (procedural justice) reduces the exit of team members (Fiet et al. 1997). Finally, company characteristics such as lower profit (Muske and Fitzgerald 2006) and larger firm size (Boeker and Karichalol 2002) have been positively associated with ETMEs.

3.2 Routes

The theme of routes is considered to be an important part of conventional entrepreneurial exits (DeTienne and Chandler 2010). This is in line with our categorization of the review articles where the routes are central for the process for ETMEs. Specifically, we emphasize the role of the nature of exits, the strategy, and the initiating actors.

Overall, there is little research on the distinct ways of how team members withdraw from an entrepreneurial team and what makes them choose their exit routes. However, research suggests distinguishing the nature of ETMEs. As such, ETMEs may be hostile or amicable, indicating a strong emotional component in the interaction of team members regarding the moment of the exit decision. Amicable team exits take place in situations where the future of the venture is at the forefront of making the decision, while hostile exits arise in times of team conflict (Loane et al. 2014).

Either way, research argues that the exit strategies should significantly differ between team and solo ventures (Wennberg and DeTienne 2014). The handling of the shares of the exiting team member, thereby, is a key strategic decision (Junkunc and Eckhardt 2009; Loane et al. 2014). There are limited studies on this topic. An exception is an article by Piva and Rossi-Lamastra (2017), who analyze how team cohesion influences the choice between selling to remaining team members or to an external buyer. They find that larger team size and family ties within the team decreases the likelihood of selling to external buyers. If the team is characterized by gender heterogeneity, the exiting individual is less likely to sell to remaining team members.

Furthermore, the findings point towards the importance of the actors responsible for the ETMEs. We refer to this as the ‘initiation actor’, which describes which of the individuals involved in the team member exit is triggering the exit (Gregori and Breitenecker 2017). The majority of articles deals with entrepreneurial team member exits initiated by stakeholders, i.e., venture capitalists (e.g., Busenitz et al. 2004; Erikson and Berg-Utby 2009) and business angels (e.g., Collewaert and Fassin 2013) or broadly termed investors (e.g., Lim et al. 2013). Additionally, we were able to identify cases where the remaining team member(s), who stay with the company after the exit, dismiss one individual of the team (e.g., Hauser et al. 2012; Loane et al. 2014). However, there are also some examples of exits triggered by the exiting individual. Here, the exiting individual confronts his/her team members with the decision to leave the entrepreneurial team (e.g., Discua Cruz et al. 2013; Goi and Kokuryo 2016). Taking this perspective of different actors reveals the complex interactions involved in dealing with exits. We argue that the initiating actor is closely related to the nature of the exit as well as the applied strategies and is, thus, an integral part for researching ETME routes.

3.3 Consequences

Unveiling the consequences of ETMEs is at the heart of current work on this topic. In line with other research (Guenther et al. 2015), we have found that consequences are inconclusive. The systematic review provides insights on both positive and negative effects of ETMEs. In distinguishing among consequences for the exiting individual, the team, and the venture, we further unfold these diverging findings.

The consequences of the exit for the exiting individual are hardly analyzed in the reviewed articles. Breugst et al. (2015) provide the only example and explain that an exiting individual isolated himself from the remaining team, the enterprise, and also from his wider social environment. He not only deleted his social media account and changed his telephone number as well as his e-mail addresses but also went abroad for a substantial amount of time. Considering the sometimes massive psychological, social and financial consequences mentioned in the entrepreneurial exit literature (Pretorius 2009; DeTienne 2010), this calls for further investigation. Speaking in terms of the parenthood metaphor of entrepreneurship (Cardon et al. 2005), the exiting entrepreneurs do not only leave their “baby”, which they had nurtured and looked after. They also leave their social environment where they spent a large amount of time to promote the development of the mutual venture and this also includes friendships with other team members (Francis and Sandberg 2000).

Research on the consequences of the exit of a member for the remaining team is more frequent and current endeavors suggests that ETMEs have profound effects on the team structure, resources, and characteristics. After an ETME, entrepreneurial teams alter their functional structure by reducing the number of functional positions within the venture (Beckman and Burton 2008). Additional empirical work in our review supports that idea and demonstrates that the roles of the remaining team members change (Vanaelst et al. 2006). Nonetheless, the departure of team members also affects resources and competencies. Eventually, they can lead to a critical lack that teams aim to compensate by hiring new members (Goi and Kokuryo 2016; Ferguson et al. 2016). Furthermore, authors claim that ETMEs alter team-level characteristics because a change in the entrepreneurial team potentially aligns the shared beliefs and views of the remaining team members. For instance, the shared vision of the team is proposed to converge when members with different beliefs depart from the team (Loane et al. 2007; Preller et al. 2015).

Consequences for the venture are manifold but inconclusive. Most of the examined studies focus on the venture performance measured by indicators such as IPO, sales, revenue, or venture capital funding. Positive effects of team member exits have been found on time until IPO, time until venture capital funding (Beckman and Burton 2008), and profitability and revenues (Chandler et al. 2005; Sine et al. 2006; Kaehr Serra and Thiel 2019). In contrast, scholars also demonstrate negative effects such as a slower rate of IPOs (Beckman et al. 2007), a decreased survival rate (Busenitz et al. 2004; Haveman and Khaire 2004; Le et al. 2017), and an increased risk of failure (Guenther et al. 2015). For instance, findings show that pre-IPO ETMEs negatively influence the firm’s performance (i.e. return for shareholders) because they reduce the knowledge and resource base of the company (Le et al. 2017). However, literature suggests that the positive and negative consequences of ETMEs cannot be solely explained by the total amount of resources lost through the leaving person because it might heavily depend on the previously inhabited role of the leaving individual (Haveman and Khaire 2004), the different needs of the specific venture development phase (Chandler et al. 2005) or exit timing issues (Guenther et al. 2015). Finding ways to explain these different outcomes is, thus, a must for any future engagement with consequences of ETMEs.

3.4 Contextual embeddedness

Another theme that has been touched upon in the articles is the contextual embeddedness of the ETMEs. The results show that different cultural contexts hold different implications for ETMEs. Entrepreneurial teams of academic spin-offs, for instance, are believed to face a set of critical junctures due to the academic setting along the process of spinning out and, thus, need to evolve and change their team compositions (Clarysse and Moray 2004; Vanaelst et al. 2006). Entrepreneurial teams consisting of family members or spouses are also subject to specific social principles, such as higher levels of trust and deeply shared values, delineating them from entrepreneurial teams in other contexts. The articles included in this review indicate that these differences underpin the formation—exit as well as additions of family members—of the entrepreneurial team (Muske and Fitzgerald 2006; Discua Cruz et al. 2013).

Additional efforts have been made to investigate environmental embeddedness in terms of industry influences on team changes. A study on the effect of highly dynamic environments on team changes shows that team departures in such environments tend to have a negative influence on firm growth (Chandler et al. 2005). Thus, the environmental conditions act as a moderator between the exit and its consequences for the venture. To further elucidate environmental embeddedness, the results of the systematic literature review offer an example for the importance of geographical proximity of venture capitalists and the entrepreneurial teams. When the team and the venture capitalists are geographically close, the entrepreneurial team tends to experience more member reductions (Heger and Tykvová 2009).

Moreover, the review reveals findings concerning the temporal embeddedness of ETMEs. Timing (operationalized through the age of the venture) can help to explain the consequences of founder exits in new venture teams. In general, there seems to be a negative effect of ETMEs on the venture performance, but this harmful effect becomes insignificant as the venture matures (Guenther et al. 2015). These findings are supported by other results positing that the stage of development of the venture is a positive moderator of the link between team member departure and venture performance (Chandler et al. 2005). The role of timing has further been investigated in terms of time until ETME. When investigating the impact of venture capitalists on the turnover of entrepreneurial teams, a higher equity stake of venture capitalists and higher venture growth rate reduces the time until an entrepreneurial team member is replaced or dismissed (Heger and Tykvová 2009). This proposes that temporal considerations are an important factor for understanding the antecedents of ETMEs and their consequences.

4 Discussion and research directions

Based on the results of the systematic literature review, this section aims to suggest potential ways to move research on ETMEs forward. To do this, we discuss the identified parts of the ETME process (antecedents, routes, consequences, contextual embeddedness) under the light of new perspectives and derive potential research questions for further engagement. An overview of these possible research questions and perspectives is provided in Table 2.

4.1 New perspectives on antecedents: expanding the heterogeneity concept and introducing faultlines

The investigated articles provide a wide range of different antecedents of ETMEs. However, a large part of these findings is anecdotal with no theoretical underpinning and, thus, often lacks an in-depth discussion in the respective article. In so far, the systematic review offers a multitude of potential influencing factors, but we do not know yet how these factors are related and how they might influence each other. Furthermore, current research indicates that some antecedents may be more ‘fatal’ than others and are more likely to lead to team changes (Diakanastasi et al. 2018). Future avenues should approach the numerous potential antecedents from multiple levels such as the individual, the team, and the organization; investigate how they are intertwined in the process of ETMEs and evaluate which of them are more influential than others. A more detailed conception and differentiation of heterogeneity serves as a promising way to start.

Team heterogeneity appears to be a core factor to understand the drivers of ETMEs. The results point towards a positive relation between ETMEs and heterogeneity as variety (e.g. functional expertise, entrepreneurial experience, education, age; Ucbasaran et al. 2003; Chandler et al. 2005; Hellerstedt et al. 2007) as well as heterogeneity as separation (e.g. diverging values and beliefs; Vanaelst et al. 2006; Discua Cruz et al. 2013). However, conclusions concerning heterogeneity as separation need to be drawn carefully because of the exploratory character of the analyzed studies. Future research, thus, should investigate the roles of differences in terms of the team members’ opinions, values, beliefs, or passion (Cardon et al. 2017) and their relation to subsequent exits.

In addition to variety and separation, heterogeneity as disparity is a third type that should be considered in team research (Harrison and Klein 2007). Heterogeneity as disparity refers to the inequality of socially valued resources (e.g., payment, status, authority, equity). We found that research on this form of heterogeneity is quite limited. Nevertheless, there are some hints towards its importance (especially the distribution of equity) that lay the foundation for further research in this regard. The distribution of shares is shown to be a core decision in entrepreneurial teams (Hellmann and Wasserman 2016). Low perceived fairness due to the distribution of shares, then, can trigger negative interaction spirals, which further lead to ETMEs (Breugst et al. 2015). In addition, research on top management teams shows that such disparities are important influencing factors for team outcomes (Nielsen 2009). Hence, we argue that heterogeneity as disparity can offer useful new concepts to explain ETMEs in future research.

Heterogeneity is one way to explore team compositions, but the systematic review excavates an additional approach to investigate the structure of diversity within entrepreneurial teams utilizing the faultlines perspective (Lim et al. 2013). Faultlines are “hypothetical dividing lines that may split a group into subgroups based on one or more attributes” (Lau and Murnighan 1998, p. 328). As opposed to team heterogeneity, which portrays the dispersion of a single attribute within a group, the strength of a faultline provides a level of (dis-) similarity of subgroups within organizations. In earlier concepts, the faultlines perspective focused on differences in demographic qualities such as age, gender, or national diversity. More recent studies have extended the initial conceptualization to integrate factors including the group members’ beliefs, personal values, or personality. Faultlines have been linked to a multitude of group outcomes such as, for example, satisfaction, conflicts, and potential member changes (Thatcher and Patel 2012). Moreover, the highly influential behavior of investors, another outcome of the systematic literature review, has been theorized to contribute to faultlines within new ventures (Lim et al. 2013). This allows scholars to bridge the team and organizational level of antecedents for ETMEs. As such, this perspective can provide us with new insights on which antecedents might be more influential, that is, strengthen faultlines among group members, within the process of ETMEs.

4.2 The role of power and negotiations in ETME routes

Considering the importance of exit routes for the processes of entrepreneurial exits (DeTienne and Chandler 2010; Piva and Rossi-Lamastra 2017), the dearth of research on this theme within ETME research is rather surprising. In terms of ETMEs, not every exit route of conventional entrepreneurial exits is readily applicable. The selling and retaining of the shares of the exiting individual is the main point of discussion in current literature (Junkunc and Eckhardt 2009; Loane et al. 2014; Piva and Rossi-Lamastra 2017) but we argue that a different approach to exit routes, namely the investigation of power and negotiations, will lead to profound insights into how ETMEs are handled.

Our results suggest the importance of the interplay among initiating actors, the nature of the exit, and the strategy to realize the exit. Taking a power perspective would allow future research to reveal the interpersonal relations and team dynamics of ETME routes. Power is the “ability to get things done the way one wants them to be done” (Salancik and Pfeffer 1977, p. 4) and, thus, the capacity of an individual actor to exert influence on a person in a group (Pfeffer 1981). Organizational research indicates the importance of power distribution among teams (Sperber and Linder 2018) and suggests that powerful actors have the ability to initiate change in companies (Greve and Mitsuhashi 2007). This coincides with the findings of the systematic review because several articles point to power disparities among the involved parties, especially between investors and the entrepreneurial team (Fiet et al. 1997; Collewaert and Fassin 2013) but also within the team itself (Loane et al. 2014). Investigating power disparities would then allow scholars to identify the initiating actors and to determine what socially valued characteristics and resources they possess to be able to enforce an exit. A way to examine the distribution of power within the team in future research is, for example, the distribution of equity (Finkelstein 1992). Upcoming empirical work can use ownership as a dimension of power, where higher shares imply more control over core decisions pertaining to the business (Kroll et al. 2007). As already discussed, the perception of fairness towards the equity distribution can be an antecedent of an ETME (Breugst et al. 2015), but the implied power and control might also be a prerequisite to be able to initiate an exit.

Moreover, our systematic review revealed a lack of insights concerning how exits are negotiated among the involved actors. Again, taking a power perspective would allow us to unravel the social hierarchical positioning of entrepreneurial team members and corporate stakeholders, thus, enlightening their possibilities in negotiating exit outcomes. This could support researchers when answering questions such as what happens to the freed up equity (Breugst et al. 2015), or how power relations change when team composition is fluid. Power influences the ability of entrepreneurs to negotiate within their teams (Ruef 2009), and entrepreneurs are found to negotiate more assertively than non-entrepreneurs, extensively utilizing emotions in their negotiation behaviors (Artinger et al. 2015). Given the potentially highly emotional context of ETMEs and the necessity to negotiate the outcomes (Cardon et al. 2005; Loane et al. 2014), we argue that ETMEs serve as extreme cases to study negotiations, providing fertile ground for new insights into entrepreneurial behaviors and the role of emotions in entrepreneurial processes.

4.3 Resolving inconsistencies of ETME consequences

The literature review reveals inconsistencies in terms of ETME consequences that need to be approached to elevate research. We suggest two ways how future research can approach this task: First, future studies need to consider and untangle the multiple levels of outcomes and rethink performance measurements and, second, ETMEs should be explored more comprehensively as a process.

4.3.1 The relation between team-level and venture-level consequences and performance measures

The systematic review shows that ETMEs are a multilevel phenomenon with consequences for the exiting individual, the remaining team, and the affected venture. Delineating among those levels is challenging, because positive team outcomes are related to positive venture performance (Vanaelst et al. 2006; West 2007; Jin et al. 2017). Therefore, when an ETME changes the structure, resources, or characteristics of the remaining team, as the results of this review uncover, we need to investigate how this in turn influences team performance in the first place. Unfortunately, current work does not provide us with insights in this regard leading us to encourage further research to be carried out in this area. Thus, we argue, that when the favorable connection between team level performance and venture performance holds as predicted by the current entrepreneurial team research (Jin et al. 2017), untangling the different levels of outcomes of an ETME could help to explain why firm-level outcomes might differ among studies that do not control for team outcomes.

Related to this, we suggest to reconsider and eventually alter the proxies used for firm performance in entrepreneurial team studies. Most studies in this field of entrepreneurial teams use growth or profitability as an absolute measure for venture performance (Klotz et al. 2014). The articles in our sample also use absolute variables such as time to IPO, profitability, or time until venture capital funding (Chandler et al. 2005; Beckman et al. 2007; Beckman and Burton 2008). The problem with this type of proxy is that it neglects the aspirations and motivations of the team members. Hence, if an entrepreneurial team does not want to grow in a distinct amount of time, the venture is still categorized as low performing (Klotz et al. 2014). This supports our notion to integrate team-level characteristics such as growth aspiration (and the changes due to the ETMEs) into future research designs. Future research might want to discuss venture outcomes in relation to the venture goals, outcome satisfaction, or well-being in conjunction with conventional financial metrics (Klotz et al. 2014).

In addition, in measuring the impact of ETMEs on venture performance, the problem of reverse causality needs to be considered. It has been shown that exits by team members lead to a decrease in the profitability of the affected venture (Chandler et al. 2005), but a reverse connection can be equally true when individual team members depart due to an unsatisfying venture performance. In such a case, scholars argue that the exiting individuals are leaving a sinking ship and that this challenge has to be approached with appropriate methods (see Le et al. 2017 for such an attempt).

4.3.2 ETMEs as a process

Framing and researching ETMEs as a process provides another avenue to clarify the impact of such an event. Our results show that none of the screened articles aim to provide a full picture of the whole process including antecedents, routes, and subsequent consequences. Research on entrepreneurial exits argues that exits are best studied as a process due to the contingency of outcomes on preceding events (Wennberg 2007; Wennberg and DeTienne 2014). Indeed, our review reveals the interrelatedness of antecedents, exit routes, and outcomes and points towards the importance to engage the contingencies of ETME consequences. Current research, for example, have shown the relations between preceding conflictual interactions of the entrepreneurial team as an antecedent leading to a hostile exit route resulting in negative individual outcomes (Breugst et al. 2015). In addition, the chronological order of events is important to further elucidate the process (Chandler et al. 2005; Heger and Tykvová 2009; Guenther et al. 2015).

Building on these findings, we argue that future research designs must consider two aspects: First, they should allow to investigate the connection of antecedents, routes, and consequences of ETMEs in a more systematic and comprehensive manner. Second, they should permit temporal aspects of ETMEs to be taken into account. Although quantitative approaches can provide important findings to illuminate different parts of the process, we suggest that especially qualitative approaches yield great potential. Longitudinal qualitative research designs for theory building provide a vehicle to analyze how events are interrelated and evolve over time, which allows capturing temporal dimensions, for example, through techniques of temporal bracketing or visual mapping (Langley 1999). Such research designs are necessary to analyze how ETMEs emerge, what antecedents precede different exit routes and how these ultimately result in diverse consequences on different levels of analysis. This could lead to different patterns of ETMEs and enlighten the relationships among the themes we derived in this review. Our process-oriented framework could, thus, provide a foundation to tackle this task.

4.4 Contextualizing ETMEs

Despite the importance of contextual factors for the process of ETMEs (Clarysse and Moray 2004; Chandler et al. 2005; Vanaelst et al. 2006), research in this regard has been quite limited. Following recent calls to contextualize entrepreneurship and to theorize its context (Welter 2011), we argue that a more fine-grained cultural contextualization of the process of ETMEs will offer profound new insights into how this entrepreneurial phenomenon takes place.

Our review provides two examples of different cultural settings that influence the way in which teams change—the academic spin-offs (Clarysse and Moray 2004; Vanaelst et al. 2006) and a family firm setting (Discua Cruz et al. 2013) that both have profound differences compared to other cultural environments (Helm and Mauroner 2007; Hiebl and Li 2018). Our review shows how entrepreneurial teams are formed between two diverging logics each with its own values, beliefs, and legitimate practices. One way to analyze this cultural embeddedness is the institutional logic perspective, which has recently gained traction in organization and entrepreneurship studies (De Clercq and Voronov 2011; Reay and Jones 2016; Gregori et al. 2019). Institutional logics are shared intersubjective meaning systems that influence individual attention, values, goals, and behaviors in providing distinct organizing principles (Friedland and Alford 1991). The logics constrain and enable individual action and provide a frame for what practices are legitimate and what ends are desirable (Thornton et al. 2012; Friedland 2018). In recent years, several ideal types of such logics have been established including a commercial market logic and a family logic (Thornton et al. 2012) as well as an academic logic that can support us in contextualizing future research on ETMEs.

The institutional logic perspective posits that actors are regularly caught between different logics leading to tensions and uncertainty (Greenwood et al. 2011). This could provide a starting point to further explore ETMEs in academic or family settings. For example, academics that are part of the team formation often do not have the necessary commitment towards the entrepreneurial endeavor, making them leave the joint enterprise (Vanaelst et al. 2006). The ideals of an academic logic can intervene with the profit maximization of the commercial market logic (Upton and Warshaw 2017), and these clashing values can constitute the motivation to withdraw (Dufays and Huybrechts 2017). The family setting offers similar friction points among values, beliefs, and goals compared to the commercial market logic. Families derive legitimacy from unconditional loyalty towards the family values and heritage, which are often not compatible with the market logic (Thornton et al. 2012). Discua-Cruz et al. (2013) provide an example for this idea when they argue that the family entrepreneurial teams are characterized by a high commitment to shared values and the commitment to the stewardship of the family’s assets. Hence, they speculate that family members who cannot fulfill their profit ambitions (market logic) exit the firm.

Taking the importance of cultural contextual embeddedness into account, future engagements may seek to answer the following question of, ‘how does the process of ETME play out under certain circumstances?’ instead of ‘does the ETME have positive or negative outcomes?’

4.5 Limitations

Like every piece of scientific work, our systematic literature review does come with limitations. Using quality criteria for the search, in our case peer-reviewed journal articles, is a double-edged sword. Although, it is a common practice and recommended for the review of literature to provide a foundation for a certain level of quality (Bouncken et al. 2015), it opens the way to missing out on potentially relevant pieces of knowledge within unpublished papers or books. However, we argue that our systematic review approach in conjunction with additional search strategies (backward citation search and handsearching) resulted in a comprehensive review with high quality articles.

We also want to point out that the inclusion and exclusion of articles and the coding procedure can be affected by the researchers’ subjectivity, where other authors might have come to different conclusions (Bouncken et al. 2015; Kraus et al. 2018). To tackle the subjectivity, we conducted an independent search strategy involving two authors and the subsequent discussion of the included and excluded articles as part of a presentation in front of other colleagues. The same is true for the coding procedure itself, where our independent coding procedure and discussion of codes aimed to reduce the inherent subjectivity of the qualitative approach.

In line with this notion, we decided to investigate current literature and derive a research agenda under a processual lens. We are convinced that a process perspective is best suited to investigate ETMEs (see also Klotz et al. 2014; Wennberg and DeTienne 2014; Guenther et al. 2015), but other conceptual approaches might also have been possible (e.g., focus on themes such as group behavior or entrepreneurial decision-making). Moreover, when we discussed potential ways to move the field forward, we found some aspects of currently proposed perspectives convincing and opted to focus on these propositions (e.g., novel perspectives of heterogeneity, faultlines, power). Other work on entrepreneurial teams offers various different ways that could help us to theorize ETMEs such as the upper echelon perspective (Jin et al. 2017), different theories of capital (Nikiforou et al. 2018), or social identity theory (Ruef 2010). Discussing all these possibilities would go beyond the scope of this review. Related to that, other fields of research such as meso-sociological studies on group behavior or research on organizational behavior could further enlighten the topic of ETMEs. However, we deliberately did not aim to open this box of vast possibilities but instead chose to give a comprehensive overview of research within the stated conceptual boundaries, especially since entrepreneurial teams are found to be greatly different than other types of teams (Schjoedt et al. 2013; Klotz et al. 2014). Future work on ETMEs could also draw connections among those other fields of research and investigate the transferability of the results.

5 Conclusion

In this endeavor, we compiled the fragmented yet growing research on ETMEs by deriving central themes within the current literature and developing a processual framework for ETMEs. Our literature review shows that current research covers insights in terms of antecedents, routes, consequences, and the contextual embeddedness. The results presented the multiple different antecedents stemming from the individual, the entrepreneurial team, or the affected venture where the concept of team heterogeneity is central. We also revealed the importance of the nature of the exit, strategies, and the initiating actors that jointly constitute the ETME routes. Such exits further have social and psychological consequences for the individual, change team structures, resources, and characteristics, and exert positive as well as negative effects on different measures for venture performance. Moreover, cultural, environmental, and temporal contexts play a pivotal role in understanding ETMEs.

Building on these results and to move the field forward, we proposed that future research should take new perspectives on ETME antecedents by expanding the concept of team heterogeneity and introducing the faultline perspective. Further, power and negotiation behavior can be a constructive way to analyze the social relations and outcomes of ETME routes. Future research is advised to disentangle the team-level and venture-level consequences and explore the ETMEs in a processual longitudinal way to resolve the sometimes inconsistent findings of venture consequences. Finally, we plead for a more in-depth contextualization, which will provide more profound insights on how ETMEs take place in different spatial and cultural contexts. We encourage other scholars to use this article as a roadmap to examine the presented aspects in more detail, to be inspired by our potential paths for future research and to derive research questions and hypothesis for the promising research on ETMEs.

References

Artinger S, Vulkan N, Shem-Tov Y (2015) Entrepreneurs’ negotiation behavior. Small Bus Econ 44:737–757. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-014-9619-8

Baldacchino L, Ucbasaran D, Cabantous L, Lockett A (2015) Entrepreneurship research on intuition: a critical analysis and research agenda. Int J Manag Rev 17:212–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12056

Bamford C, Bruton G, Hinson Y (2006) Founder/chief executive officer exit: a social capital perspective of new ventures. J Small Bus Manag 44:207–220

Beckman CM, Burton MD (2008) Founding the future: path dependence in the evolution of top management teams from founding to IPO. Organ Sci 19:3–24. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1070.0311

Beckman CM, Burton MD, O’Reilly C (2007) Early teams: the impact of team demography on VC financing and going public. J Bus Ventur 22:147–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2006.02.001

Ben-Hafaïedh C, Cooney TM (2017) Research handbook on entrepreneurial teams: theory and practice. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham

Bjørnåli ES, Gulbrandsen M (2010) Exploring board formation and evolution of board composition in academic spin-offs. J Technol Transf 35:92–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-009-9115-5

Boeker W, Karichalol R (2002) Entrepreneurial transitions: factors influencing founder departure. Acad Manag J 45:818–826

Boeker W, Wiltbank R (2005) New venture evolution and managerial capabilities. Organ Sci 16:123–133

Bouncken RB, Gast J, Kraus S, Bogers M (2015) Coopetition: a systematic review, synthesis, and future research directions. Rev Manag Sci 9:577–601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-015-0168-6

Breugst N, Patzelt H, Rathgeber P (2015) How should we divide the pie? Equity distribution and its impact on entrepreneurial teams. J Bus Ventur 30:66–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.006

Busenitz LW, Fiet JO, Moesel DD (2004) Reconsidering the venture capitalists’ “value added” proposition: an interorganizational learning perspective. J Bus Ventur 19:787–807. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.06.005

Cardon MS, Zietsma C, Saparito P et al (2005) A tale of passion: new insights into entrepreneurship from a parenthood metaphor. J Bus Ventur 20:23–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.01.002

Cardon MS, Post C, Forster WR (2017) Team entrepreneurial passion: its emergence and influence in new venture teams. Acad Manag Rev 42:283–305. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0356

Chandler GN, Honig B, Wiklund J (2005) Antecedents, moderators, and performance consequences of membership change in new venture teams. J Bus Ventur 20:705–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.09.001

Clarysse B, Moray N (2004) A process study of entrepreneurial team formation: the case of a research-based spin-off. J Bus Ventur 19:55–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00113-1

Collewaert V (2012) Angel investors’ and entrepreneurs’ intentions to exit their ventures: a conflict perspective. Entrep Theory Pract 36:753–779. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00456.x

Collewaert V, Fassin Y (2013) Conflicts between entrepreneurs and investors: the impact of perceived unethical behavior. Small Bus Econ 40:635–649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9379-7

Cooney TM (2005) Editorial: what is an entrepreneurial team? Int Small Bus J 23:226–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242605052131

Cooper AC, Bruno AV (1977) Success among high-technology firms. Bus Horiz 20:16–22

Crossan MM, Apaydin M (2010) A multi-dimensional framework of organizational innovation: a systematic review of the literature. J Manag Stud 47:1154–1191. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00880.x

D’hont L, Doern R, Delgado García JB (2016) The role of friendship in the formation and development of entrepreneurial teams and ventures. J Small Bus Enterp Dev 23:528–561. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-02-2015-0027

De Clercq D, Voronov M (2011) Sustainability in entrepreneurship: a tale of two logics. Int Small Bus J 29:322–344. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610372460

de Mol E, Khapova SN, Elfring T (2015) Entrepreneurial team cognition: a review. Int J Manag Rev 17:232–255. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12055

Dehlen T, Zellweger T, Kammerlander N, Halter F (2014) The role of information asymmetry in the choice of entrepreneurial exit routes. J Bus Ventur 29:193–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.10.001

DeTienne DR (2010) Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: theoretical development. J Bus Ventur 25:203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.05.004

DeTienne DR, Cardon MS (2012) Impact of founder experience on exit intentions. Small Bus Econ 38:351–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9284-5

DeTienne DR, Chandler GN (2010) The impact of motivation and causation and effectuation approaches on exit strategies. Front Entrep Res 30:1–13

DeTienne D, Wennberg K (2016) Studying exit from entrepreneurship: new directions and insights. Int Small Bus J 34:151–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615601202

Diakanastasi E, Karagiannaki A, Pramatari K (2018) Entrepreneurial team dynamics and new venture creation process: an exploratory study within a start-up incubator. SAGE Open 8:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244018781446

Discua Cruz A, Howorth C, Hamilton E (2013) Intrafamily entrepreneurship: the formation and membership of family entrepreneurial teams. Entrep Theory Pract 37:17–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00534.x

Drazin R, Kazanjian RK (1993) Applying the del technique to the analysis of cross-classification data: a test of ceo succession and top management team development. Acad Manag J 36:1374–1399. https://doi.org/10.2307/256816

Dufays F, Huybrechts B (2017) Entrepreneurial teams in social entrepreneurship: when team heterogeneity facilitates organizational hybridity. In: Ben-Hafaïedh C, Cooney TM (eds) Research handbook on entrepreneurial teams. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 273–290

Eisenhardt KM (2013) Top management teams and the performance of entrepreneurial firms. Small Bus Econ 40:805–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9473-0

Eisenhardt KM, Schoonhoven CB (1990) Organizational Growth: linking Founding Team, Strategy, Environment, and Growth Among U.S. Semiconductor Ventures, 1978–1988. Adm Sci Q 35:504. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393315

Ensley MD, Hmieleski KM (2005) A comparative study of new venture top management team composition, dynamics and performance between university-based and independent start-ups. Res Policy 34:1091–1105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2005.05.008

Ensley MD, Carland JW, Carland JC (1998) The effect of entrepreneurial team skill heterogeneity and functional diversity on new venture performance. J Bus Entrep 10:1–14

Ensley MD, Pearson AW, Amasone AC (2002) Understanding the dynamics of new venture top management teams—Cohesion, conflict, and new venture performance. J Bus Ventur 17:365–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0883-9026(00)00065-3

Erikson T, Berg-Utby T (2009) Preinvestment negotiation characteristics and dismissal in venture capital-backed firms. Negot J 25:41–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1571-9979.2008.00207.x

Ferguson AJ, Cohen LE, Burton MD, Beckman CM (2016) Misfit and milestones: structural elaboration and capability reinforcement in the evolution of entrepreneurial top management teams. Acad Manag J 59:1430–1450. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0526

Fiet JO, Busenitz LW, Moesel DD, Barney JB (1997) Complementary theoretical perspectives on the dismissal of new venture team members. J Bus Ventur 12:347–366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00015-3

Finkelstein S (1992) Power in top management teams: dimensions, measurement, and validation. Acad Manag J 35:505–538

Forbes DP, Borchert PS, Zellmer-Bruhn ME, Sapienza HJ (2006) Entrepreneurial team formation: an exploration of new member addition. Entrep Theory Pract 30:225–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00119.x

Francis DH, Sandberg WR (2000) Friendship within entrepreneurial teams and its association with team and venture performance. Entrep Theory Pract 26:5–26

Friedland R (2018) Moving institutional logics forward: emotion and meaningful material practice. Organ Stud 39:515–542. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840617709307

Friedland R, Alford RR (1991) Bringing society back in: symbols, practices, and institutional contradictions. In: DiMaggio PJ, Powell WW (eds) The new institutionalism in organizational analysis. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp 232–266

Gartner WB, Shaver KG, Gatewood E, Katz JA (1994) Finding the entrepreneur in entrepreneurship. Entrep Theory Pract 18:1–5

Gioia DA, Corley KG, Hamilton AL (2013) Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research. Organ Res Methods 16:15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

Goi HC, Kokuryo J (2016) Design of a university-based venture gestation program (UVGP). J Enterprising Cult 24:1–35. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0218495816500011

Greenwood R, Raynard M, Kodeih F et al (2011) Institutional complexity and organizational responses. Acad Manag Ann 5:317–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2011.590299

Gregori P, Breitenecker RJ (2017) Entrepreneurial Team Member Exits—Initiation and Reasons. In: 21st Interdisziplinäre Jahreskonferenz zu Entrepreneurship, Innovation und Mittelstand, Bergische Universität Wuppertal, Germany, 5–6 October 2017. pp 1–22

Gregori P, Wdowiak MA, Schwarz EJ, Holzmann P (2019) Exploring value creation in sustainable entrepreneurship: insights from the institutional logics perspective and the business model lens. Sustainability 11:2505. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11092505

Greve HR, Mitsuhashi H (2007) Power and glory: concentrated power in top management teams. Organ Stud 28:1197–1221. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607075674

Grilli L (2011) When the going gets tough, do the tough get going? The pre-entry work experience of founders and high-tech start-up survival during an industry crisis. Int Small Bus J 29:626–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610372845

Guenther C, Oertel S, Walgenbach P (2015) It’s all about timing: age-dependent consequences of founder exits and new member additions. Entrep Theory Pract 40:843–865. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12148

Harper DA (2008) Towards a theory of entrepreneurial teams. J Bus Ventur 23:613–626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.01.002

Harrison D, Klein KJ (2007) What’s the difference? diversity constructs as separation, variety, or disparity in organizations. Acad Manag Rev 32:1199–1228. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2007.26586096

Hauser C, Moog P, Werner A (2012) Internationalisation in new ventures—what role do team dynamics play? Int J Entrep Small Bus 15:23. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJESB.2012.044587

Haveman HA, Khaire MV (2004) Survival beyond succession? The contingent impact of founder succession on organizational failure. J Bus Ventur 19:437–463. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(03)00039-9

Heger D, Tykvová T (2009) Do venture capitalists give founders their walking papers? J Corp Financ 15:613–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2009.07.001

Hellerstedt K (2009) The composition of new venture teams. International Business School, Jönköping

Hellerstedt K, Aldrich HE, Wiklund J (2007) The impact of past performance on the exit of team members in young firms: the role of team composition. Front Entrep Res 27:1–14

Hellmann T, Puri M (2002) Venture capital and the professionalization of start-uup firms: empirical evidence. J Finance 57:169–197

Hellmann T, Wasserman N (2016) The first deal: the division of founder equity in new ventures. Manag Sci 1:1. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2016.2474

Helm R, Mauroner O (2007) Success of research-based spin-offs. State-of-the-art and guidelines for further research. Rev Manag Sci 1:237–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-007-0010-x

Hiebl MRW, Li Z (2018) Non-family managers in family firms: review, integrative framework and future research agenda. Rev Manag Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-018-0308-x

Jin L, Madison K, Kraiczy ND et al (2017) Entrepreneurial team composition characteristics and new venture performance: a meta-analysis. Entrep Theory Pract 41:743–771. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12232

Junkunc MT, Eckhardt JT (2009) Technical specialized knowledge and secondary shares in initial public offerings. Manag Sci 55:1670–1687. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1090.1051

Kaehr Serra C, Thiel J (2019) Professionalizing entrepreneurial firms: managing the challenges and outcomes of founder-CEO succession. Strateg Entrep J 13:379–409. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1329

Kamm JB, Shuman JC, Seeger JA, Nurick AJ (1990) Entrepreneurial teams in new venture creation: a research agenda. Entrep Theory Pract 14:7–17

Klotz AC, Hmieleski KM, Bradley BH, Busenitz LW (2014) New venture teams: a review of the literature and roadmap for future research. J Manage 40:226–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313493325

Kraus S, Palmer C, Kailer N et al (2018) Digital entrepreneurship: a research agenda on new business models for the twnety-first century. Int J Entrep Behav Res 25:353–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijebr-06-2018-0425

Kroll M, Walters BA, Son LA (2007) The impact of board composition and top management team ownership structure on post-IPO performance in young entrepreneurial firms. Acad Manag J 50:1198–1216. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159920

Langley A (1999) Strategies for theorizing from process data. Acad Manag Rev 24:691. https://doi.org/10.2307/259349

Lau DC, Murnighan JK (1998) Demographic diversity and faultlines: the compositional dynamics of organizational groups. Acad Manag Rev 23:325–340. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1998.533229

Lazar M, Miron-Spektor E, Agarwal R et al (2019) Entrepreneurial team formation. Acad Manag Ann Annals 14:1. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2017.0131

Le S, Kroll M, Walters B (2017) TMT departures and post-IPO outside director additions: implications for young ipo firms’ survival and performance. J Small Bus Manag 55:149–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12245

Lechler T (2001) Social interaction: a determinant of entrepreneurial team venture success. Small Bus Econ 16:263–278. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011167519304

Lim JY-K, Busenitz LW, Chidambaram L (2013) New venture teams and the quality of business opportunities identified: faultlines between subgroups of founders and investors. Entrep Theory Pract 37:47–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00550.x

Loane S, Bell J, McNaughton R (2007) A cross-national study on the impact of management teams on the rapid internationalization of small firms. J World Bus 42:489–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2007.06.009

Loane S, Bell J, Cunningham I (2014) Entrepreneurial founding team exits in rapidly internationalising SMEs: a double edged sword. Int Bus Rev 23:468–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.11.006

Muske G, Fitzgerald MA (2006) A panel study of copreneurs in business: who enters, continues, and exits? Fam Bus Rev 19:193–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2006.00070.x

Nabi G, Liñán F, Fayolle A et al (2017) The impact of entrepreneurship education in higher education: a systematic review and research agenda. Acad Manag Learn Educ 16:277–299. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2015.0026

Nielsen S (2009) Top management team diversity: a review of theories and methodologies. Int J Manag Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00263.x

Nikiforou A, Zabara T, Clarysse B, Gruber M (2018) The role of teams in academic spin-offs. Acad Manag Perspect 32:78–103. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2016.0148

Parastuty Z, Schwarz EJ, Breitenecker RJ, Harms R (2015) Organizational change: a review of theoretical conceptions that explain how and why young firms change. Rev Manag Sci 9:241–259. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-014-0155-3

Pfeffer J (1981) Power in organizations. Pitman, Marshfield

Piva E, Rossi-Lamastra C (2017) Should I sell my shares to an external buyer? The role of the entrepreneurial team in entrepreneurial exit. Int Small Bus J. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242616676310

Preller R, Breugst N, Patzelt H (2015) Do we all see the same future? The impact of entrepreneurial team members’ visions on team and venture development. Front Entrep Res 35:196–201

Pret T, Cogan A (2018) Artisan entrepreneurship: a systematic literature review and research agenda. Int J Entrep Behav Res IJEBR 25:592–614. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijebr-03-2018-0178

Pretorius M (2009) Defining business decline, failure and turnaround: a content analysis. S Afr J Entrep Small Bus Manag 2:1–16

Reay T, Jones C (2016) Qualitatively capturing institutional logics. Strateg Organ 14:441–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127015589981

Ronstadt R (1986) Exit, stage left why entrepreneurs end their entrepreneurial careers before retirement. J Bus Ventur 1:323–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(86)90008-X

Rosenstein J, Bruno AV, Bygrave WD, Taylor NT (1993) The CEO, venture capitalists, and the board. J Bus Ventur 8:99–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(93)90014-V

Ruef M (2009) Economic inequality among entrepreneurs. Res Sociol Work 18:57–87

Ruef M (2010) The entrepreneurial group: social identities, relations, and collective action. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Sageder M, Mitter C, Feldbauer-Durstmüller B (2018) Image and reputation of family firms: a systematic literature review of the state of research. Rev Manag Sci 12:335–377. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-016-0216-x

Salancik GR, Pfeffer J (1977) Who gets power—and how they hold on to it: a strategic-contingency model of power. Organ Dyn 5:3–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-2616(77)90028-6

Schjoedt L, Kraus S (2009) Entrepreneurial teams: definition and performance factors. Manag Res News 32:513–524. https://doi.org/10.1108/01409170910962957

Schjoedt L, Monsen E, Pearson A et al (2013) New venture and family business teams: understanding team formation, composition, behaviors, and performance. Entrep Theory Pract 37:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00549.x

Sine WD, Mitsuhashi H, Kirsch DA (2006) Revisiting burns and stalker: formal structure and new venture performance in emerging economic sectors. Acad Manag J 49:121–132. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20785590

Sperber S, Linder C (2018) The impact of top management teams on firm innovativeness: a configurational analysis of demographic characteristics, leadership style and team power distribution. Rev Manag Sci 12:285–316. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-016-0222-z

Thatcher SMB, Patel PC (2012) Group faultlines: a review, integration, and guide to future research. J Manage 38:969–1009. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311426187

Thiess D, Sirén C, Grichnik D (2016) How does heterogeneity in experience influence the performance of nascent venture teams?: insights from the US PSED II study. J Bus Ventur Insights 5:55–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2016.04.001

Thornton PH, Ocasio W, Lounsbury M (2012) The institutional logics perspective: a new approach to culture, structure, and process. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Tranfield D, Denyer D, Smart P (2003) Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. Br J Manag 14:207–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.00375

Ucbasaran D, Lockett A, Wright M, Westhead P (2003) Entrepreneurial founder teams: factors associated with member entry and exit. Entrep Theory Pract 28:107–128. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1540-6520.2003.00034.x

Upton S, Warshaw JB (2017) Evidence of hybrid institutional logics in the US public research university. J High Educ Policy Manag 39:89–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2017.1254380

Vanaelst I, Clarysse B, Wright M et al (2006) Entrepreneurial team development in academic spinouts: an examination of team heterogeneity. Entrep Theory Pract 30:249–271. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00120.x

Visintin F, Pittino D (2014) Founding team composition and early performance of university—Based spin-off companies. Technovation 34:31–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2013.09.004

Wang CL, Chugh H (2014) Entrepreneurial learning: past research and future challenges. Int J Manag Rev 16:24–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12007

Welter F (2011) Contextualizing entrepreneurship-conceptual challenges and ways forward. Entrep Theory Pract 35:165–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00427.x

Wennberg K (2007) Entrepreneurial exit. Economic Research Institute, Stockholm School of Economics (EFI), Stockholm

Wennberg K, DeTienne DR (2014) What do we really mean when we talk about “exit”? A critical review of research on entrepreneurial exit. Int Small Bus J 32:4–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242613517126