Abstract

Maintaining the highest levels of patient safety is a priority of healthcare organisations. However, although considerable resources are invested in improving safety, patients still suffer avoidable harm. The aims of this study are: (1) to examine the extent, range, and nature of patient safety research activities carried out in the Republic of Ireland (RoI); (2) make recommendations for future research; and (3) consider how these recommendations align with the Health Service Executive’s (HSE) patient safety strategy. A five-stage scoping review methodology was used to synthesise the published research literature on patient safety carried out in the RoI: (1) identify the research question; (2) identify relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) chart the data; and (5) collate, summarise, and report the results. Electronic searches were conducted across five electronic databases. A total of 31 papers met the inclusion criteria. Of the 24 papers concerned with measuring and monitoring safety, 12 (50%) assessed past harm, 4 (16.7%) the reliability of safety systems, 4 (16.7%) sensitivity to operations, 9 (37.5%) anticipation and preparedness, and 2 (8.3%) integration and learning. Of the six intervention papers, three (50%) were concerned with education and training, two (33.3%) with simplification and standardisation, and one (16.7%) with checklists. One paper was concerned with identifying potential safety interventions. There is a modest, but growing, body of patient safety research conducted in the RoI. It is hoped that this review will provide direction to researchers, healthcare practitioners, and health service managers, in how to build upon existing research in order to improve patient safety.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A commitment to improving safe healthcare features in governmental policies worldwide. However, progress in delivering on this aspiration has been modest, with patients still suffering avoidable harm [1]. A major challenge to improving safety is the lack of high-quality information to allow healthcare organisations, teams, and individuals to evaluate how they are performing, and where there are deficits and risks [2]. This safety information is complex and multi-faceted, yet vitally important if safety is to improve [3].

In the Republic of Ireland (RoI), “maintaining the highest levels of patient safety is a fundamental priority for patients and for healthcare organisations”(p.5) [4]. The need for proactive approaches to patient safety has been identified by the Irish Health Service Executive (HSE) [4]. There is a recognition that such an approach requires high-quality data that will support learning from patient safety incidents, identification of hazards or risks, and the implementation of interventions to improve safety [4]. It is only through effective measurement and monitoring of safety (MMS) that comparisons can be made between the safety performance of different healthcare organisations, the impact of safety interventions can be assessed, and there can be a shift to a more proactive approach to safety.

In addition to efforts to improve the MMS, there is also a need to consider the effectiveness of patient safety interventions. There has been considerable investment in patient safety improvement efforts, for which there may be limited evidence of effectiveness [5]. It has been found that the majority of safety interventions tend to be person-focused (e.g. education and training), with more effective systems focused interventions far less commonplace [6]. Moreover, high-quality research on the effectiveness of safety intervention is lacking [5]. Therefore, there is a need for rigorous assessment of the effectiveness of interventions to ensure that they are having the desired effect, and the resources required to implement such interventions are justified. Crucially, given the recognised impact of context on intervention implementation and effectiveness, such assessments must be conducted within different healthcare systems and services [7].

The purpose of this scoping review is to examine the extent, range, and nature of patient research activities carried out in the RoI. Research is fundamental to improving practice, particularly within an applied science such as patient safety [8]. Accordingly, the findings from this review will be used to make recommendations for future patient safety research, and the alignment between these recommendations and the HSE patient safety strategy 2019–2024 [4] will be delineated.

Methods

This scoping review is conducted using the five-stage approach proposed by Arksey and O’Malley [9] and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist [10]. Scoping reviews provide an increasingly popular option for synthesising and mapping evidence in healthcare research [11].

Stage 1: Identify the research question

The purpose of the review was clearly defined with concept of interest (i.e. patient safety research), target population (i.e. healthcare staff and patients in secondary care), and location (i.e. RoI).

Stage 2: Identify relevant studies

Search strategy

Electronic searches were conducted across five electronic databases in July 2021: Medline, CINAHL, Embase, PsycInfo, and Web of Science. The search strategy was finalised by a Research Librarian (RD). The search strategy comprised Medical Subject Headings terms along with free-text keywords, and was altered as necessary for the remaining databases (see Supplementary Data 1 [12] for the Medline search strategy). In addition to electronic searches, the reference lists of all studies identified as eligible for inclusion from the electronic searches were screened to identify any other potentially suitable articles.

Stage 3: Study selection

Titles and abstracts of all articles identified during the electronic searches were screened by one of three authors (ROM, YK, or ESP) in July 2021. The full-texts of articles that appeared eligible for inclusion, or articles in which the title and abstract did not provide sufficient information for the determination to be made, were reviewed in full to confirm their eligibility. For papers where inclusion was unclear, all members of the research team reviewed the paper, and decisions on eligibility were made through discussion.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria required that studies: (1) were focused on patient safety in hospitals in the RoI including, but not limited to, the measurement of safety or implementation of initiatives aimed at improving safety; (2) reported original research; (3) were published in a peer-reviewed journal; and (4) were written in English.

Exclusion criteria

Studies were excluded if they: (1) focused on patient safety in the context of patients with a particular medical condition only (e.g. patients with cancer); (2) focused on the safety of one process only (e.g. medication errors); (3) were conducted in healthcare settings other than hospitals; (4) were conducted in a country other than the RoI or a sample of countries including the RoI where RoI-specific data could not be extracted; (5) only employed one item/question relating to patient safety as part of a larger survey or assessment (i.e. studies had to use a full measure of patient safety); or (6) did not report original research. No limits were placed on the publication year.

Stage 4: Chart the data

A preliminary data charting form was developed in accordance with best practice [13], and piloted by two authors (YK, ROM). The form was used to extract data on author(s), year of publication, study location, study aim, methods, sample, intervention (if included), comparator (if included), outcome measures, and key reported outcomes. Data were extracted by three authors (ROM, YK, and ESP), with two of these authors extracting data independently for each included article. Disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Stage 5: Collate, summarise, and report the results

The characteristics of the included studies were collated and summarised across several key descriptors: location; aim; methods; sample; type and duration of intervention (if applicable); comparators (if applicable); outcome measures; and key outcomes.

Included studies were summarised according to one of two different frameworks. Studies that involved MMS were categorised using the five domains of Vincent et al. [3, 14] MMS framework (see Table 1). It was possible for both studies and measures described to be categorised under more than one MMS dimension.

Studies of a safety intervention were classified using the hierarchy of intervention effectiveness framework [15] (see Table 1). The framework delineates interventions according to six levels of effectiveness from 1 (most effective) to 6 (least effective). The hierarchy of intervention effectiveness framework was first discussed by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, and has since been referenced a number of patient safety organisations as an approach to guide the identification of suitable safety interventions (e.g. Incident Analysis Collaborating Parties [16], Health Information and Quality Authority [17]). The hierarchy of interventions was extended by Woods et al. [18], who added three additional levels (staff organisation, risk assessment, learning from errors, and personal initiative) as this was deemed necessary in order to appropriately classify solutions to improving clinical communication and patient safety. However, for the purposes of this scoping review, we used the original six level framework due to our focus on interventions, rather than solutions (see Table 1).

The categorisation of study content via these two frameworks was carried out independently by three reviewers (ROM, YK, and ESP). Where disagreements arose, the study was discussed by all members of the review team and a decision on the categorisation was made by consensus. Following completion of all data charting and coding, the meaning of the findings and their implications were appraised within the context of the broader literature in this area, and the HSE patient safety strategy [4].

Results

A total of 6515 articles were identified from electronic database searches (see Fig. 1), with 170 full-texts examined and 27 papers ultimately meeting the inclusion criteria. Four additional studies were identified through reference list screening, resulting in the inclusion of 31 studies (published 2003–2021). Study characteristics are outlined in Table 2, and a summary of the main findings from the studies is provided in Table 3.

Studies focused on past harm

Past harm was the most frequently assessed dimension of the MMS framework, and was measured in 12 studies (see Tables 2 and 3, and Online Supplementary Material 2 [12]). Six studies employed surveys to measure past harm. Two of these studies used surveys to estimate the frequency of a range of adverse events [19] and to examine nurse adverse event reporting rates [20]. Of the four remaining studies that used a survey design, two examined the association of burnout with self-reported medical error and poor-quality care [21, 22], and two studies explored nurse incident reporting [23, 24]. Four studies measured past harm by retrospectively reviewing patient records. Two of these record reviews were undertaken as part of the Irish National Adverse Events studies [1, 25], and examined trends in adverse event rates in the Irish healthcare system. The two remaining record reviews were conducted to estimate the economic cost of nurse-sensitive adverse events [26] and to compare the health system performance of 15 Organisation for Economic Co-operation (OECD) countries across seven patient safety indicators [27]. Furthermore, one study used a combination of survey and interview methods to examine the nature and frequency of medical error among junior doctors [28], and one study comprised a review of medico-legal claims to identify current adverse event reporting trends in Irish surgical specialties [29].

Studies focused on reliability of safety critical processes

Four studies assessed the reliability of safety critical processes (see Tables 2 and 3, and Online Supplementary Material 2 [12]). Of the two studies that used a survey design to monitor reliability, one study employed surveys to examine the implementation of Surgical Safety Checklists (SSC) in Irish operating theatres [30] while the other study used interviews to develop a survey evaluating the attitudes of theatre staff towards a surgical checklist [31]. Two studies used patient record review methodology to assess reliability, one of which reviewed patient records to assess the prevalence of surgical checklist use in Europe [32] while the other study used hospital data to improve the international comparability of patient safety indicators [27].

Studies focused on sensitivity to operations

Four studies included a measure that assessed sensitivity to operations (see Tables 2 and 3, and Online Supplementary Material 2 [12]). Three of these studies used surveys and asked nurses to give their ward an overall safety grade [19, 20, 33]. One study conducted interviews to explore aspects of safety culture that were important to the staff at the time of the interviews [34].

Studies focused on anticipation and preparedness

Almost a third of the included studies focused on anticipation and preparedness (see Tables 2 and 3, and Online Supplementary Material 2 [12]). Five studies used surveys to assess patient safety culture. Three of these studies employed the Safety Attitudes Questionnaire (SAQ) [35,36,37], and two studies used items from other surveys [19, 20]. Interviews and/or observations were used by three studies to investigate healthcare workers’ perceptions of the safety culture [34] and to explore how nurses promote safety in perioperative settings [38, 39]. One study used in situ simulation to examine latent safety hazards in response to preparation for an expected COVID-19 surge [40].

Studies focused on integration and learning

Integration and learning was assessed by two studies (see Tables 2 and 3, and Online Supplementary Material 2 [12]). McNamara and O' Donoghue [41] reviewed patient records to objectively demonstrate if a change in labour ward clinical activity occurred following serious adverse perinatal events. Jee et al. [40] identified system errors and latent safety hazards using in situ simulation and described the resulting corrective measures taken to improve their pandemic response locally.

Intervention studies

Six studies were categorised as intervention studies. Studies employed several different types of intervention of varying effectiveness (see Tables 2 and 3, and Online Supplementary Material 2 [12]). Three studies comprised interventions that focused on improving patient safety through education and training [42,43,44]. One of these studies implemented a board game to educate junior doctors about patient safety and the importance of reporting safety concerns [42]. The second educational intervention was concerned with training aimed at improving interns’ attitudes towards, and ability to, “speak up” to senior physicians [43], and the third comprised an online patient safety education programme for junior doctors [44].

Two of the studies implemented interventions focused on improving safety through simplification and standardisation. Both of these studies involved the implementation of an incident/near miss reporting form [45] or complication proforma [46]. Finally, one study sought to improve patient safety by implementing an intervention focused on reminders, checklists, and double checks. This intervention involved the development and implementation of an adhesive surgical ward round checklist [47].

There was one study included in the review that was not concerned with MMS or constituted an intervention itself. Rather, the focus of this study was on the development of a collective leadership intervention for healthcare teams to improve team performance and patient safety culture [48].

Discussion

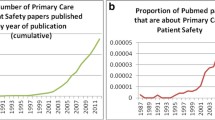

This scoping review has demonstrated that, although overall modest in size, there is a growing body of research on patient safety in the RoI published in peer-reviewed journals—particularly in recent years. This growth is consistent with the action from the HSE patient safety strategy “to support patient safety research and publish and act on the results” (p.19]) [4]. The majority of the research on MMS in the RoI was focused on measuring past harm (particularly adverse events), and anticipation and preparedness (particularly assessments of safety culture/climate). Most of the intervention studies were concerned with education and training. We will make recommendations for areas of future research based on the findings from the scoping review, and identify how these recommendations align with relevant aims from the HSE patient safety strategy 2019–2024 [4].

The focus on adverse events as a method of measuring past harm is consistent with the substantial increase in research publications on this approach to measuring safety in healthcare [49]. Staff surveys are a commonly used source of information on adverse events. However, a survey approach is constrained by the extent to which conclusions can be drawn about adverse event prevalence. Patient record review has been considered the “gold standard” patient safety research method [50], and was used in four of the reviewed studies. Such data are useful in demonstrating the scope of the problem in the Irish healthcare system, allows for international comparisons, and for an assessment of any changes over time. However, patient record review data are limited in terms of identifying specific areas for safety improvement [50, 51]. Therefore, there is a need for measures tailored to distinct aspects of patient harm (e.g. specific care-related injuries, missed diagnoses that lead to harm) [50]. Such data is important to address the HSE goal to “measure and monitor safety, to evaluate the effects of safety improvement initiatives, and to inform further emerging priorities”(p.19) [4]. Data on specific aspects of patient harm will allow the alignment of adverse events with failures in care, and the development and evaluation of interventions to address these issues [52].

Safety culture/climate surveys were the most frequently used approach to measuring and monitoring anticipation and preparedness. Again, this is consistent with the large amount of research devoted to these types of measures more broadly in the safety literature [53, 54]. Safety culture/climate data is useful in identifying areas of both strength and weakness. However, it has been suggested that such survey measures may be best viewed as a trusted “wet finger” to find out which way the wind blows [55], and do not identify specific areas for improvement. To illustrate, working conditions were identified as an area for improvement across four of the included studies [34–37]. However, further data is required to identify the specific working conditions that should be prioritised for change. This is why, in some safety culture interventions, the survey data is used to inform discussion in qualitative safety culture workshops to identify the specific issues that need to be addressed [56]. It is recommended that future research should consider how to measure safety culture/climate in a way that is practical, sufficiently specific to identify areas for safety improvement, and can be used to measure whether improvements have occurred. This will likely require a combination of quantitative and qualitative data collection methodologies. A consideration of how to measure safety culture/climate is particularly important in the RoI as this has been identified as a specific action in the HSE patient safety strategy [4].

Compared to the MMS dimensions of past harm and anticipation and preparedness, a lower number of studies in our scoping review were concerned with MMS in the other three safety dimensions—particularly integration and learning. These proportions are similar to the findings from a systematic review of MMS in prehospital care [51]. Although the studies in our scoping review that assessed one of these three dimensions of MMS provided informative data, they were largely based upon staff survey responses. Only one study [41] utilised clinical data. It is suggested that consideration should be given to the identification of feasible methods to MMS in these three under-researched dimensions beyond that derived only from survey data. A robust safety surveillance system should comprise multiple methods and address all five MMS domains. Research is recommended to critically appraise the existing safety monitoring system in the RoI healthcare system in order to identify blind spots as well as where there may be duplication of effort. Such research is consistent with the HSE patient safety strategy aim to “further develop and enhance local and national suites of key patient safety indicators” (p. 19) [4].

Although MMS is important, what is also essential is that this data is used to identify and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to improve patient safety and quality of care [52]. In fact, there is arguably little point in collecting safety data if it is not then used to bring about improvement. Three out of the six safety interventions identified were focused on education and training—a person-focused intervention at the lowest level of the hierarchy of intervention effectiveness [15]. Although two interventions [45, 46] with a focus on simplification and standardisation were identified, no interventions were found at the highest two levels of the hierarchy—forcing functions, automation and computerisation. The evaluations of the interventions included in the review were positive. However, similar to the majority of assessments of patient safety interventions, the quality of the evidence of effectiveness was low, with limited evidence of an impact on patient outcomes [5, 57, 58]. It is recommended that future research focuses on the evaluation of more effective system-focused interventions. It is further recommended that interventions are closely aligned to appropriate, and meaningful, measures of MMS in order to support rigour in evaluation of the impact of interventions on patient safety. This alignment will be necessary to achieve the HSE patient safety aims of putting in place appropriate actions to mitigate risks to patients, prioritising specific safety improvement initiatives, and evaluating the effects of safety improvement and risk mitigation initiatives [4]. It is also suggested that the co-design approach used by Ward et al. [48] may offer a useful approach to identify specific interventions that healthcare staff believe will improve safety.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to our scoping review. Firstly, a quality assessment was not carried out, although this absence is consistent with the majority of other scoping reviews [59]. Secondly, our scoping review provided a more descriptive summary of the literature than would be the case from a systematic review. This is a result of the goal of a scoping review to provide a map of existing research, rather than to answer a specific question [60]. Thirdly, as in any synthesis of the literature, scoping reviews are at risk for bias [60]. Fourthly, studies that focused on patient safety in the context of patients with a particular medical condition or focused on the safety of one process were excluded from our review. The rationale for this exclusion was that it would have been impossible to devise a search strategy that included every possible medical condition, and process. Therefore, we chose to take an approach that included all papers that met the inclusion criteria rather than an approach that, although broader, may have missed particular studies. Finally, we did not carry out a search of the grey literature. These searches were not carried out as there are methodological issues with including grey literature searches in systematic reviews (e.g. compromised methodological reproducibility, difficulties in interpreting these publications [61]).

Conclusion

There is a modest, but growing, body of patient safety research conducted in the RoI. This scoping review has demonstrated the variety of patient safety research being carried out in the RoI. It is hoped that this review will provide direction to researchers, healthcare practitioners, and health service managers, in how to build upon the existing research in order to improve patient safety and quality of care.

References

Rafter N, Hickey A, Conroy RM et al (2017) The Irish National Adverse Events Study (INAES): the frequency and nature of adverse events in Irish hospitals-a retrospective record review study. BMJ Qual Saf 26(2):111–119

Dixon-Woods M, Baker R, Charles K et al (2014) Culture and behaviour in the English National Health Service: overview of lessons from a large multimethod study. BMJ Qual Saf 23(2):106–115

Vincent C, Burnett S, Carthey J (2013) The measurement and monitoring of safety: drawing together academic evidence and practical experience to produce a framework for safety measurement and monitoring. The Health Foundation, London

Health Services Executive (2019) Patient safety strategy 2019–2024. Dublin: Author

Zegers M, Hesselink G, Geense W et al (2016) Evidence-based interventions to reduce adverse events in hospitals: a systematic review of systematic reviews. BMJ Open 6(9):e012555

Soong C, Shojania KG (2020) Education as a low-value improvement intervention: often necessary but rarely sufficient. BMJ Qual Saf 29:353–357

Øvretveit JC, Shekelle PG, Dy SM et al (2011) How does context affect interventions to improve patient safety? An assessment of evidence from studies of five patient safety practices and proposals for research. BMJ Qual Saf 20(7):604–610

Pronovost PJ, Goeschel CA, Marsteller JA et al (2009) Framework for patient safety research and improvement. Circ 119(2):330–337

Arksey H, O’Malley L (2005) Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Method 8(1):19–32

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W et al (2018) PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annal Int Med 169(7):467–473

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK (2010) Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci 5(1):1–9

O’Connor P, O’Malley, Kaud Y et al (2022) A scoping review of patient safety research carried out in the Republic of Ireland. Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5846748.

Peters MD, Godfrey C, McInerney P et al (2020) Scoping reviews. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z (Eds). JBI manual for evidence synthesis (pp. 406–451). Adeleide, Austalia: JBI Global

Vincent C, Burnett S, Carthey J (2014) Safety measurement and monitoring in healthcare: a framework to guide clinical teams and healthcare organisations in maintaining safety. BMJ Qual Saf 23(8):670–677

Institute for Safe Medication Practices (1999) Medication error prevention toolbox. ISMP Med Saf Alert 4:1–2

Incident Analysis Collaborating Parties (2012) Canadian incident analysis framework. Edmont AB: Canad Patient Saf Inst

Health Information and Quality Authority (2018) Medication safety monitoring programme in public acute hospitals- an overview of findings. Dublin: Author

Woods DM, Holl JL, Angst D et al (2008) Improving clinical communication and patient safety: clinician-recommended solutions. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA (eds)Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches (Vol 3: performance and tools) (pp. 1–18). Henriksen Rockville, MD: Agen Healthcare Res Qual

Aiken LH, Sloane DM, Bruyneel L et al (2013) Nurses’ reports of working conditions and hospital quality of care in 12 countries in Europe. Int J Nurs Stud 50(2):143–153

Kirwan M, Matthews A, Scott PA (2013) The impact of the work environment of nurses on patient safety outcomes: a multi-level modelling approach. Int J Nurs Stud 50(2):253–263

O’Connor P, Lydon S, O’Dea A et al (2017) A longitudinal and multicentre study of burnout and error in Irish junior doctors. Postgrad Med J 93(1105):660–664

Sulaiman CFC, Henn P, Smith S et al (2017) Burnout syndrome among non-consultant hospital doctors in Ireland: relationship with self-reported patient care. Int J Qual Saf Health 29(5):679–684

Moore L, McAuliffe E (2010) Is inadequate response to whistleblowing perpetuating a culture of silence in hospitals?. Clin Gov 15(3):166–178

Moore L, McAuliffe E (2012) To report or not to report? Why some nurses are reluctant to whistleblow. Clin Gov 17(4):332–342

Connolly W, Rafter N, Conroy RM et al (2021) The Irish National Adverse Event Study-2 (INAES-2): longitudinal trends in adverse event rates in the Irish healthcare system. BMJ Qual Saf 30(7):547–558

Murphy A, Griffiths P, Duffield C et al (2021) Estimating the economic cost of nurse sensitive adverse events amongst patients in medical and surgical settings. J Adv Nurs 77(8):3379–3388

Drosler SE, Romano PS, Tancredi DJ et al (2012) International comparability of patient safety indicators in 15 OECD member countries: a methodological approach of adjustment by secondary diagnoses. Health Serv Res 47(1):275–292

O’Connor P, Lydon S, Mongan O et al (2019) A mixed-methods examination of the nature and frequency of medical error among junior doctors. Postgrad Med J 95(1129):583–589

Breathnach O, Cousins G, Dunne D et al (2011) A review of adverse event reporting in Irish surgical specialties. Clin Risk 17(2):43–49

Nugent E, Hseino H, Ryan K et al (2013) The surgical safety checklist survey: a national perspective on patient safety. Ir J Med Sci 182(2):171–176

O’Connor P, Reddin C, O’Sullivan M et al (2013) Surgical checklists: the human factor. Pat Saf Surg 7(1):14

Jammer I, Ahmad T, Aldecoa C et al (2015) Point prevalence of surgical checklist use in Europe: relationship with hospital mortality. Br J Anaesth 114(5):801–807

Aiken LH, Sermeus W, Van den Heede K et al (2012) Patient safety, satisfaction, and quality of hospital care: cross sectional surveys of nurses and patients in 12 countries in Europe and the United States. BMJ (Clin Res Ed) 344:e1717

Gleeson LL, O’Brien GL, O’Mahony D et al (2021) Thirst for change in a challenging environment: healthcare providers’ perceptions of safety culture in a large Irish teaching hospital. Ir J Med Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02611-5

Dwyer L, Smith A, McDermott R et al (2018) Staff attitudes towards patient safety culture and working conditions in an Irish tertiary neonatal unit. Ir Med J 111(7):786

Gleeson LL, Tobin L, O’Brien GL et al (2020) Safety culture in a major accredited Irish university teaching hospital: a mixed methods study using the safety attitudes questionnaire. Ir J Med Sci 189(4):1171–1178

Relihan E, Glynn S, Daly D et al (2009) Measuring and benchmarking safety culture: application of the safety attitudes questionnaire to an acute medical admissions unit. Ir J Med Sci 178(4):433–439

O’Brien B, Andrews T, Savage E (2019) Nurses keeping patients safe by managing risk in perioperative settings: a classic grounded theory study. J Nurs Manag 27(7):1454–1461

O’Brien B, Andrews T, Savage E (2018) Anticipatory vigilance: a grounded theory study of minimising risk within the perioperative setting. J Clin Nurs 27(1–2):247–256

Jee M, Khamoudes D, Brennan AM et al (2020) COVID-19 outbreak response for an emergency department using in situ simulation. Cureus 12(4):e7876

McNamara K, O’Donoghue K (2019) The perceived effect of serious adverse perinatal events on clinical practice. Can it be objectively measured? Euro J Obst Gyn Repod Bio 240:267–272

Ward M, Ni She E, De Brun A et al (2019) The co-design, implementation and evaluation of a serious board game PlayDecide patient safety to educate junior doctors about patient safety and the importance of reporting safety concerns. BMC Med Ed 19(1):232

O’Connor P, Byrne D, O’Dea A et al (2013) Excuse me: teaching interns to speak up. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 39(9):426–431

McCarthy SE, O’Boyle CA, O’Shaughnessy A et al (2016) Online patient safety education programme for junior doctors: is it worthwhile?. Ir J Med Sci 185(1):51–58

McElhinney J, Heffernan O (2003) Using clinical risk management as a means of enhancing patient safety: the Irish experience. Int J Health Care Qual Assur 16(2–3):90–98

McVeigh TP, Waters PS, Murphy R et al (2013) Increasing reporting of adverse events to improve the educational value of the morbidity and mortality conference. J Amer Coll Surg 216(1):50–56

Dhillon P, Murphy RKJ, Ali H et al (2011) Development of an adhesive surgical ward round checklist: a technique to improve patient safety. Ir Med J 104(10):303–305

Ward ME, De Brún A, Beirne D et al (2018) Using co-design to develop a collective leadership intervention for healthcare teams to improve safety culture. Int J Environ Res Pub Health 15(6):1182

Stelfox HT, Palmisani S, Scurlock C et al (2006) The to err is human report and the patient safety literature. BMJ Qual Saf 15(3):174–178

Shojania KG, Marang-van de Mheen PJ (2020) Identifying adverse events: reflections on an imperfect gold standard after 20 years of patient safety research. BMJ Qual Saf 29:265–270

O’Connor P, O’Malley R, Oglesby AM et al (2021) Measurement and monitoring patient safety in prehospital care: a systematic review. Int J Qual Saf Health 33(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzab013

Sauro K, Ghali WA, Stelfox HT (2020) Measuring safety of healthcare: an exercise in futility?. BMJ Qual Saf 29(4):341–344

Alsalem G, Bowie P, Morrison J (2018) Assessing safety climate in acute hospital settings: a systematic review of the adequacy of the psychometric properties of survey measurement tools. BMC Health Serv Res 18(1):1–14

Waterson P, Carman E-M, Manser T et al (2019) Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture (HSPSC): a systematic review of the psychometric properties of 62 international studies. BMJ Open 9(9):e026896

Guldenmund FW (2007) The use of questionnaires in safety culture research–an evaluation. Saf Sci 45(6):723–743

Madden C, Lydon S, Cupples ME et al (2019) Safety in primary care (SAP-C): a randomised, controlled feasibility study in two different healthcare systems. BMC Fam Prac 20(1):22

Kirkman MA, Sevdalis N, Arora S et al (2015) The outcomes of recent patient safety education interventions for trainee physicians and medical students: a systematic review. BMJ Open 5(5):e007705

O’Dea A, O’Connor P, Keogh I (2014) A meta-analysis of the effectiveness of crew resource management training in acute care domains. Postgrad Med J 90(1070):699–708

Rumrill PD, Fitzgerald SM, Merchant WR (2010) Using scoping literature reviews as a means of understanding and interpreting existing literature. Work (Reading, Mass) 35(3):399–404

Sucharew H, Macaluso M (2019) Methods for research evidence synthesis: the scoping review approach. J Hosp Med 14(7):416–418

Mahood Q, Van Eerd D, Irvin E (2014). Searching for grey literature for systematic reviews: challenges and benefits. Res Synth Meth 5(3):221–234

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the IReL Consortium.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Connor, P., O’Malley, R., Kaud, Y. et al. A scoping review of patient safety research carried out in the Republic of Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 192, 1–9 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-02930-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-022-02930-1