Abstract

Trioza erytreae, the African citrus psyllid, is a vector of Candidatus Liberibacter spp., the causal agent of the citrus greening disease or Huanglongbing (HLB). The spread of the vector throughout the Iberian Peninsula has been continuous since its introduction in mainland Spain in 2014. The patterns of host preference and feeding behaviour largely depend on olfactory cues. Understanding these patterns is crucial to prevent further dispersion and develop management measures against the pest. In this work, a series of settlement, olfactometric, probing, and feeding experiments were conducted to assess the host preference of T. erytreae for lemon or bitter orange plants. The settlement experiment provided evidence on the preference of both sexes of T. erytreae for lemon plants, whereas males did not show any significant choice pattern in the case of the olfactometric assays. Forty EPG variables were analysed to describe and compare the probing and feeding behaviour of T. erytreae on lemon and bitter orange plants. The EPG variables indicated that T. erytreae has some difficulties in accepting the phloem of bitter orange plants. This suggests that lemon plants would be a better source for the acquisition of Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas) by T. erytreae since the psyllid spends much longer periods feeding from the phloem on lemon than on bitter orange.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The citrus greening disease or Huanglongbing (HLB) (Garnier et al. 2000) is the most devastating disease of citrus plants worldwide (Bove 2006). The transmission of the causal agent of greening, the phloem-limited Gram-negative bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter spp., is driven by two natural vectors, Diaphorina citri Kuwayama, 1908 (Hemiptera: Liviidae), responsible for the propagation of Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas) and Candidatus Liberibacter americanus (CLam), and Trioza erytreae Del Guercio, 1918 (Hemiptera: Triozidae), responsible for the propagation of Candidatus Liberibacter africanus (Magomere et al. 2009; Cocuzza et al. 2016; Siverio et al. 2017). Once inoculated, the bacterium affects the vascular system of the plant resulting in dead branches, yellowing of leaves, and the appearance of deformed green fruits. Leaves may appear with spots and the fruits have a bitter taste (thus losing much of its economic value) and even the death of the plant entailing severe economic annual losses (Deng et al. 2019; Gottwald et al. 2007; Silva et al. 2016).

The African citrus psyllid, T. erytreae, is widely distributed across the African continent, but is also present in Europe (Spain and Portugal) and Saudi Arabia. According to Pérez-Otero et al. 2015, T. erytreae can feed on 18 species of Rutaceae, laying the eggs and developing the nymphs on 15 and 13 species, respectively, with a special preference for the lemon crop (Citrus limon L.). Since its introduction in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula in 2014, T. erytreae has continued to spread to southern, northern, and coastal territories of Spain and Portugal raising alarm amongst stakeholders throughout the Mediterranean basin (Benhadi-Marín et al. 2020). The acquisition of the bacterium can occur during the feeding process at different stages of the development cycle, although adults are responsible for the transmission and dissemination of the disease due to their higher spread rates. Some studies have found that T. erytreae adults can fly for at least 1.5 km, especially when forced by the lack of flushes (van den Berg and Deacon 1988).

Accordingly, uncovering patterns of host preference and feeding behaviour is crucial to prevent dispersion and development of management measures against T. erytreae. However, the role of the olfactory cues for either highly specific or oligophagous psyllids such as T. erytreae is still poorly understood. Species such as Cacopsylla bidens (Šulc, 1907), the pear psyllid, has been observed to respond to volatile cues from both the host plant and conspecifics using olfactometric and electroantennographic assays (Soroker et al. 2004). On the contrary, Farnier et al. (2018) did not find patterns of positive chemotaxis to volatiles of undamaged leaves of Eucalyptus L'Hér on different Eucalyptus-feeding psyllids. However, little is still known regarding the preference of T. erytreae for olfactory stimuli emitted by different host plants. Besides olfactory and visual cues that are mainly involved in the initial steps of host plant selection, psyllids use gustatory cues to identify and feed on their preferred hosts.

The feeding behaviour of a sap-sucking insect is not directly observable, but can be monitored using the electrical penetration graph (EPG) technique (Tjallingii 1978). This technique has been used to investigate insect–plant interactions, including the characterization and localization of host plant resistance in aphids (Helden and Tjallingii 1993; Garzo et al. 2002). In addition to aphids, EPGs have been used to assess the feeding preference of the potato psyllid, Bactericera cockerelli on different host and non-host plants (Sandanayaka et al. 2019). They concluded that EPGs is a valuable tool for rapid assessment of plants at risk of feeding damage from a phloem sap feeder. Antolinez et al. (2017a) found that the psyllid Bactericera trigonica showed preference to ingest from the phloem, settle, and oviposit on carrot and celery but not on potato, whilst Bactericera tremblayi preferred leek over carrot and potato, the latter being the less preferred host.

In addition, EPGs have been used to understand the feeding activities associated to the transmission of CLas by its vector D. citri (Bonani et al. 2010) and the transmission of CaLsol (Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum) by the psyllid B. trigonica (Antolinez et al. 2017b). EPGs shown that the transmission of CaLsol occurs when psyllids salivate in a period as short as 30 s in the phloem sieve elements (waveform E1) but not during the first phloem contact (waveform D) (Antolinez et al. 2017b).

This work aimed to investigate the attraction and preference of T. erytreae for lemon and bitter orange plants. We studied the settlement, probing, and feeding behaviour of T. erytreae and their attraction to olfactory cues emitted by citrus plants. The plant species selected for our study were lemon and bitter orange. These citrus trees are widely spread in home gardens, parks, and small orchards across the coastal regions of northern Portugal and Galicia (Spain). In our study we used a series of observational, olfactometric, video tracking, and electrophysiological techniques to characterize the behavioural response of T. erytreae to both lemon and bitter orange plants.

Material and methods

Origin and rearing of insects

The individuals of T. erytreae used in all experiments were collected from pesticide-free lemon trees in a commercial grove located at Caracoi (district of Porto, Portugal; 41°18′46.4"N 8°38′09.7"W). Adult psyllids were captured using a hand aspirator from young flushes and collected into conical centrifuge tubes (50 mL). The insects were transported to the laboratory and the colony was maintained on lemon and bitter orange plants in acrylic cages (40 cm in length, 30 cm in width, and 43 cm in height) covered by an insect-proof net. The cages were placed in a climate chamber at 21 ± 1 °C, 50 ± 5% RH and a photoperiod of 16:8 (L:D) h. The colony was fed on plants of Citrus limon (L.) (lemon) and Citrus aurantium L. (bitter orange) sown from seeds collected at the experimental farm. The plants were grown up to ~ 15 cm in height in plastic pots (6.5 cm in height, 9 cm in diameter) and maintained in a pest-free greenhouse.

Dual-choice settlement experiments

Settlement preference of adult individuals of T. erytreae was assessed on lemon and bitter orange plants. Two plants, one lemon and one bitter orange grown up to 20 cm, were placed at the opposite position inside of a polyurethane box (60 × 60 × 60 cm). The upper part of the box was covered with a mesh to allow air circulation. Young psyllid adults (1–7 days after emergence) were used and each individual was starved for 2 h before the assay. A single insect was released at the surface of the bottom of the box between the two plants. The choice made by the insect was recorded after 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 h. A total of 25 males and 25 females were tested (i.e. a set of 50 assays in total). Plants were rotated at each of the rounds to avoid positional bias. Experiments were conducted at 21 ± 2 °C, 60 ± 5% RH, and a photoperiod of 16:8 (L:D) h.

Olfactometric dual-choice experiments

Olfactometric assays were conducted to assess the response of T. erytreae to scent of C. limon (lemon) and C. aurantium (bitter orange). A four-arm olfactometer was mounted using two vacuum pumps (type N86KN.18; Pmax = 2.4 bar; KNF Neuberger Inc.) coupled to two single flow tube rotameters (Model P, 082–02-N, AALBORG®) set at 800 mL/min to generate a uniform airflow. The air stream was conducted through the whole system using plastic aquarium flexible tubes (0.5 cm in diameter). Each air stream was passed through an active carbon filter. Each filter consisted of a glass bottle filled with 0.5 L of distilled water and 3 g of activated charcoal (AppliChem, Panreac ITW ©). After filtering, each flow was split into two air currents. Each new air current was directed to a glass cup (27 cm in height, 10.5 cm in diameter) containing a single plant (i.e. a total of two lemon and two bitter orange plants grown up to 20 cm). Finally, the air stream containing the plant scent was directed towards a four-entry arena.

The arena was built in acrylic using four overlapping acrylic layers (4 mm in height). The bottom layer was a 25 × 25 cm white-opaline plate; the second and third layers consisted of a series of two overlapping white-opaline triangles (12 × 12 × 17 cm) placed at each corner of the bottom layer to create the inner space for the insects. The upper layer consisted of a 25 × 25 cm transparent plate with a central hole (4 mm in diameter) to allow the insect release and airflow. This scheme resulted in four air entries at the central point of each side of the arena (1 cm in length, 8 mm in height). Each entry provided the air scent of a single plant in alternate positions. A choice was considered when the individual accessed a designed area of ~ 1.4 cm2 around each air entry (Fig. S1). The arena was placed on a four-legged support (22 cm in height) carrying a circular lamp (17 cm in diameter) consisting of 20 white-cold LEDs at its base. The lamp was oriented upwards so that the arena was illuminated from below (negative contrast). The whole arena received 7500 ± 10 lx from below. After light filtering by the white-opaline plate of the arena, the experimental surface received 700 ± 10 lx from below and 265 ± 10 lx from above of direct white-cold fluorescent light.

Assays were carried out in a climate chamber at 21 ± 1 °C, 50 ± 5% RH, and a photoperiod of 16:8 (L:D) h. Each psyllid was starved for 2 h before the assay. A single insect was released at the central area of the arena and the moving behaviour was video-recorded during 20 min. The position of the set of entries was rotated 90º for each assay to avoid positional bias. The videos were recorded using a Computar® lens (H2Z0414C-MP, f = 4–8 mm, F 1.4, ½”, CCTV lens) mounted on a Basler ® GigE HD Camera (acA1300-60gc with e2v EV76C560 CMOS sensor) and the Media Recorder 2.5 software (Noldus Media Recorder 2013). Then, the frequency (i.e. the number of times that the individual chose the odour of each plant) and the latency (i.e. the time (seconds) that it took to the individual to choose lemon or bitter orange odour for the first time) were calculated using the video tracking software Noldus Ethovision XT 11.5 (Noldus et al. 2001). A total of 120 adult individuals (60 males and 60 females) were recorded. For each replicated assay, a pair of each plant species (2 lemon and 2 bitter orange plants) was randomly chosen amongst a pool of 12 lemon and 12 orange plants so that each pair of plants was used to test 10 insects. Each assay was replicated six times for each sex (a total of 60 males and 60 females were used).

Probing and feeding behaviour experiments

The electrical penetration graph (EPG) technique was used to evaluate the probing and feeding behaviour of T. erytreae on lemon and bitter orange seedlings (at the 4-leaf stage) following the same methodology as described by Bonani et al. (2010). The EPG recordings were obtained using a DC monitor, GIGA-8d model (EPG Systems, the Netherlands) (Tjallingii 1978), adjusted to 100 × gain. Young adult psyllids were maintained in a refrigerator at 4 °C for 30 s to reduce their activity and immediately immobilized by a vacuum device, under a dissection microscope. Then a gold wire (2 cm long and 18.5 μm of diameter; Sigmund Cohn, Mount Vernon, NY, USA), previously connected to a copper electrode (3 cm long and 1 mm in diameter), was attached to the psyllid prothorax using water-based silver conductive paint glue (EPG Systems, the Netherlands). Then the insects were connected to the EPG device and placed on the abaxial surface of the last expanded citrus leaf. Another electrode (copper, 10 cm long × 2 mm wide) was inserted into the pot substrate containing the citrus seedling. The EPG recordings lasted 8 h and were conducted inside a Faraday cage (100 × 110 × 90 cm) to avoid electrical noise. Only those EPG recordings with an optimal signal quality were considered for analysis. A total of 15 and 16 recordings (replicates) on lemon and bitter orange were recorded and analysed, respectively. A single psyllid and plant combination were used for each replicate. Each plant was used only once for each insect. Once an EPG recording was finished the plant was discarded and replaced by a new one.

The EPG waveforms were characterized according to the previous EPG studies conducted on the psyllids D. citri (Bonani et al., 2010) and B. trigonica (Antolinez et al., 2017b) as follows: non-probing (np), no stylet contact with leaf tissue; probe, all stylet activities into the plant tissue including intercellular apoplastic stylet pathway (C), initial stylet contact with phloem tissues (D), salivation into the phloem sieve elements (E1), passive phloem sap uptake (E2), and active intake of xylem sap (G). The output given by the EPG-Excel data Worksheet v5.0 (Sarria et al. 2009) for each given insect (replicate) was used for calculating the treatment mean for each of the EPG variables.

Only the most relevant EPG variables (Online Resource: Table S1) for our study were calculated as follows: number of waveform events for each insect calculated as the number of times that a particular waveform occurs for each insect; total waveform duration for each insect calculated as the total duration of a waveform, summed over all occurrences of the waveform for each insect. If no event for a particular insect occurred, then the value considered was 0; and Mean duration of waveform events for each insect was calculated as the total waveform duration divided by the number of waveform events for each insect. If no event for a particular waveform exists, then the value considered was a missing data. The E2 index or potential phloem ingestion index (Girma et al. 1992) was calculated as:

The value of each insect (replicate) was compared amongst treatments (lemon versus bitter orange plants) using the statistical tests described below.

Data analysis

Dual-choice settlement and olfactometric dual-choice experiments

The position of the insect (i.e. lemon, orange, or away from plant) according to time since release was assessed using multinomial logistic regression (α < 0.05). The position of the insect was used as response variable (away from the plant was used as baseline for modelling) and the interaction between sex and time lapse as explanatory variable. p-values were calculated using Wald tests (z tests). Then, the number of times each individual was observed settled on a plant after 24 h was compared using a generalized linear model (α < 0.05) with Poisson distribution. Sex, plant, and the interaction between the two terms were considered explanatory variables. Model validation was visually carried out checking for patterns on the residuals vs. fitted values plot. The frequency of each area was accessed and the corresponding latency were compared between plants using a Student's t test (α < 0.05) for males and females separately. Models were developed in R software v.3.5.1 (R Core Team, 2018).

Probing and feeding behaviour experiments

The probing and feeding behaviour of T. erytreae on lemon and bitter orange plants were compared using appropriate statistical tests depending on the distribution of the data. Raw data were checked for normality and homogeneity of variance using the Shapiro–Wilk W test before performing the parametric test. Data were transformed by \(\mathrm{ln}x+1\) or \(\sqrt{x+1}\), to reduce heteroscedasticity. The data that followed the Gaussian distribution were analysed by Student’s t test (p < 0.05). When data were not normally distributed, a non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test (p < 0.05) was performed. All statistical comparisons were made using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY).

Results

Dual-choice settlement assays

The interaction between elapsed time after release and sex had a statistically significant effect (χ2 = 67.7; df = 4; p < 0.001) on the choice of plant (Females × time lapse for lemon: Z = 4.25, p < 0.01; Females × time lapse for orange: Z = 3.27, p < 0.01; Males × time lapse for lemon: Z = 5.59, p < 0.01; Males × time lapse for orange: Z = 5.90, p < 0.01). After 24 h, the probability of a lemon plant being chosen was 0.58 for females and 0.59 for males, whereas the probability of an orange plant being chosen was 0.39 in the case of males and 0.18 in the case of females (Fig. 1). Considering the number of times an individual was observed settled on a plant, the interaction between plant type and sex was not statistically significant (χ2 = 2.74; df = 1; p = 0.098). The number of times an individual settled was significantly higher on lemon than on an orange plant (χ2 = 31.82; df = 1; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2a). On the other hand, the sex of the individuals had no statistically significant effect on the choice of plant (χ2 = 5, 46; df = 1; p = 0.02) (Fig. 2b).

Number of observations (mean ± 95% CI) after 24 h of the location of T. erytreae according to the plant and the sex of the insect. a Effect of the plant on the number of observations; b effect of sex on the number of observations. Different letters above bars indicate statistically significant differences (p < 0.001)

Olfactometry assays

Regarding the olfactometric assays, both the frequency of visits and the latency accessing each of the four areas were significantly higher on insects approaching lemon than bitter orange in the case of females (Table 1). Although the same choice pattern was found for males, no significant differences were detected in this case (Table 1).

Probing and feeding behaviour experiments

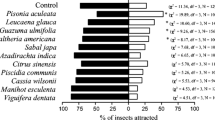

Forty EPG variables were analysed (Online Resource: Table S1) to describe and compare the probing and feeding behaviour of T. erytreae on two different citrus species, lemon and bitter orange plants. The results (Fig. 3 and Online Resource: Table S1) indicated that T. erytreae strongly prefers to feed on lemon than on bitter orange plants. Insects exposed to bitter orange exhibited more non-probing events than those on lemon plants (13.81 ± 2.72; 7.00 ± 1.18, respectively; U = 62.00 p = 0.021). Similarly, we observed a higher number of probes on orange (13.56 ± 2.70) than on lemon plants (6.93 ± 1.15) (U = 63.50 p = 0.025). However, the total probing time was not significantly different between both citrus species (orange: 20,486.72 ± 1042.85 s; lemon: 22,201.54 ± 1321.64; U = 153.00 p = 0.192). When we evaluated the stylet activities performed by the insect during the probing time we observed that T. erytreae spent significantly more time in intercellular apoplastic stylet pathway (waveform C) on orange than on lemon plants (Total duration of C orange: 13,724.92 ± 757.55 s; lemon: 8425.01 ± 982.89 s; t = 4.303 p < 0.001). Conversely, psyllids spent more time in passive phloem ingestion (E2) on lemon than on orange plants (Total duration of E2 orange: 4218.83 ± 882.66 s; lemon: 10,408.96 ± 2125.42 s; t = 2.460 p = 0.020; % of probing time spent on E2 orange: 18.63 ± 3.42 and lemon: 42.10 ± 7.58; t = − 2.882 p = 0.016). Also the potential E2 index was more than twice as high on lemon than on orange plants (Fig. 3c and Online Resource: Table S1).

EPG variable values (mean ± SE) during the probing and feeding behaviour of Trioza erytreae on lemon and bitter orange plants. Only those variables that showed significant differences have been represented in this figure. a Number of waveform events for each insect; b total waveform duration for each insect; c percentage of time of those variables that are associated with phloem activities. Non-probe (np) is a flat line associated to non-probing behaviour (no stylet contact with leaf tissue); probe, all stylet activities into the plant tissue including intercellular apoplastic stylet pathway (C), initial stylet contact with phloem tissues (D), salivation into the phloem sieve elements (E1), passive phloem sap uptake (E2), and active intake of xylem sap (G). *Significant differences (p ≤ 0.05) according to the t test for variables with Gaussian distribution and Mann–Whitney U test for variables with non-Gaussian distribution

Our EPG results did not show evidence of deterrence or delays in probing behaviour of psyllids on lemon or orange plants as the time elapsed from the beginning of the EPG recording until the first probe was not significantly different (lemon: 2328.78 ± 842.40 s; orange: 1355.60 ± 234.74 s; p = 0.401) (Online Resource: Table S1). Furthermore, no significant differences were observed in the number and duration of xylem sap ingestion (waveform G) made by psyllids on bitter orange and lemon plants.

Discussion

Host plant selection by sap-sucking insects is a complex of sequence behaviours or successive stages that finally end in the acceptance or rejection of a plant as a feeding source (Powell et al. 2006). In the early stages of host plant selection process both physical and chemical stimuli are particularly important. First, insects are visually attracted to plant-reflected wavelengths (mainly in the yellow-green part of the visual spectrum). Then, volatiles emitted by plants can also play an important role in the landing and settlement behaviour of sap-sucking insects (Eigenbrode et al. 2002; Fereres et al. 2016). In the case of psyllids, there are several examples where volatiles emitted by plants can modify the arrestment and settlement behaviour. Volatiles play an essential role as olfactory cues by D. citri during the host plant selection process (Wenninger et al. 2009). Furthermore, adults of D. citri were attracted to specific volatiles emitted by CLas-infected plants more than to those from non-infected counterparts (Mann et al. 2012).

In our work, we found a clear preference of T. erytreae for volatiles emitted by lemon than to those from bitter orange plants. Our results are consistent with Moran (1968) that found a high preference (due to either feeding or ovipositioning) of T. erytreae for lemon plants in South Africa compared to different indigenous host plants (Vepris undulaia (Thunb.) Verdoorn et Sm., Clausena anisata (Willd.) Hook. f. ex Benth., Fagara capensis Thunb., Calodendrum capem (L. f.) (Thunb.). Moreover, our results also agree with those of Aidoo et al. (2019) that reported clear patterns of preferences amongst rutaceous and non-rutaceous plants in Kenya. Attraction and arrestment of T. erytreae to lemon plants seem to be related to the presence of specific terpenes (limonene, sabinene, and β-ocimene) present in lemon flushing leaves. These terpenes play a very important role in the arrestment and host plant selection process of T. erytreae has recently shown by Antwi-Agyakwa et al. (2019).

Our T. erytreae settlement experiments revealed an increasing probability to find an individual on lemon plants, in turn, significantly higher than on bitter orange plants. Although no significant differences between males and females were found considering the number of observations on a plant after 24 h, the multinomial model revealed a significant interaction between sex and preference. Notwithstanding, Soroker et al. (2004) also found that males and females of C. bidens differed in their preferences using a Y-olfactometer. Moreover, the olfactometric assays also showed that females were more responsive to odours than males and accessed the lemon areas more often than males. Interestingly, the significantly higher latency of females than males for entering a lemon area could be because of their higher exploring rate to search for an optimal oviposition source, although further specific experiments are required to test this hypothesis. Also, Antwi-Agyakwa et al. (2019) found that lemon leaf odours attracted only females, although synthetic mixtures of lemon flushing leaf terpenes caused varying behavioural responses from both sexes.

The pool of individuals used for our assays was reared randomly on lemon and bitter orange plants and this could be a source of bias for subsequent feeding choices. In fact, rearing on a specific plant species may affect the host preference behaviour of D. citri (Stockton et al. 2017) although Moran (1968) found that the rearing plant species did not affect further host preference even in colonies of T. erytreae maintained during two generations. Other species such as the carrot psyllid Trioza apicalis Foerster, 1848 exhibit a strong response to hexane extracts of Daucus carota L. (Kristoffersen et al. 2008). On the contrary, another natural vector of HLB, D. citri did not exhibit any behavioural response to individual volatiles emitted by Duncan grapefruit (Citrus paradisi Macfayden) and sweet orange (Citrus sinensis L.) (Amorós et al. 2019). Accordingly, these authors suggested that a complex blend would be necessary to induce a higher number of catches on yellow sticky traps in a context of pest control. In fact, Wenninger et al. (2009) found, using olfactometry, that mated females of D. citri showed different behavioural responses to the odour of fresh leaves of C. paradisi, Citrus aurantium L., C. sinensis, and Murraya paniculata L. Jack. More recently, Volpe et al. (2020) found that D. citri responded to volatiles emitted by flushing orange plants and that the airflow in the range of 0.1 to 0.4 LPM was a critical factor in the behavioural response. All these studies suggest that psyllids including T. erytreae are attracted to plant volatiles emitted by their preferred host plants.

Besides visual and olfactory cues, psyllids use gustatory cues during feeding to select their preferred host plants once they land and settle on a given plant. Sandayanaka et al. (2019) found that the psyllid B. cockerelli was able to discriminate between host plants, which could support sustained feeding, and non-host plants that could not. Their study shows that an EPG continuous recording period of 10 h provided the most accurate prediction of host plant suitability by B. cockerelli. Thus, EPGs are a valuable tool to identify which are the preferred hosts for psyllids. Actually, the feeding behaviour of psyllids such as T. apicalis, B. cockerelli, B. trigonica, B. tremblayi, and more extensively of D. citri has been studied using the EPG technique in the past (Pearson et al. 2014; Sandanayaka et al. 2014; Collins et al. 2014; Antolinez et al. 2017b; George et al. 2018; Ebert et al. 2018). However, there is only a single study on the feeding behaviour of T. erytreae (Quintana-González de Chaves et al. 2020). They compared the feeding behaviour of T. erytreae on host plant, citrus (bitter orange) versus a non-host (carrot plants). They observed that only few psyllids were able to show phloem activities (4 out of 14 showed salivation (E1) and 3 out of 14 showed phloem sap ingestion (E2)) in citrus plants whilst no phloem phase activities were observed in carrot plants. However, in our study, we observed that the number of individuals of T. erytreae that showed phloem activities on bitter orange was higher (bitter orange: 15 out of 16 for E1 and 14 out of 16 for E2) than in the study reported by Quintana-González de Chaves et al. (2020). Similar results were obtained with lemon plants where all psyllids were able to reach and feed from the phloem. This discrepancy between the two studies could be related with the differences in the phenological stage of the seedlings used in both studies. The bitter orange plants used by Quintana-González de Chaves et al. (2020) were at the 7–10-day-old stage whilst in our study they were at the 4-leaf stage when the feeding behaviour assays were conducted. Previous studies shown that the phenological stage of citrus plants plays an important role in host plant acceptance by T. erytreae because this psyllid species prefers to feed on young leaves or flushes than on mature leaves (Catling, 1971). Furthermore, studies carried out with D. citri showed strong preference to ingest phloem sap from immature and young leaves than from mature citrus leaves (Ebert et al. 2018).

Our EPG results clearly indicated that the psyllid T. erytreae prefers to feed on lemon than on bitter orange plants. They spent longer periods of phloem sap ingestion on lemon than on bitter orange plants and more importantly the potential E2 index was much higher for lemon than for bitter orange. The potential E2 index also called potential phloem ingestion index represents the acceptability of the phloem by the insect. Previous studies have shown that the E2 index gives a very good estimation of host plant susceptibility (Girma et al. 1992). We observed that the contribution of E1 to phloem phase was twice as much on orange than on lemon plants (Online Resource: Table S1). It is well known that sap-sucking insects extend their salivation phase in the phloem (E1) when they have feeding difficulties (Will et al. 2009). All these EPG variables indicate that T. erytreae has some difficulties in accepting the phloem of orange plants and that they preferred lemon plants as a feeding source. Overall, our results are consistent with observations of our field surveys conducted in Galicia (Spain) and the North of Portugal that show that T. erytreae infestations are much more common in lemon than in bitter orange (unpublished data).

Trioza erytreae showed longer periods of phloem sap ingestion on lemon, activity that is associated with a high efficiency of transmission of CLas. According to studies by Bonani et al. (2010), CLas was detected in 6% of D. citri adults from a total of 50 individuals that made an E2 waveform for a period of 1 h. Furthermore, George et al. (2018) found that longer feeding time in the phloem is associated to a more efficient acquisition of CLas by D. citri from infected plants. Our EPG results showed that the mean duration of phloem sap ingestion (E2) was shorter than 1 h on bitter orange (689.64 s) but much longer on lemon plants (4911.35 s). This fact suggests that lemon plants would be a better source than bitter orange for the transmission of CLas by T. erytreae because this psyllid species prefers to ingest phloem sap for much longer periods on lemon than on bitter orange.

Our work shows that lemons are more preferred host plants than bitter orange for T. erytreae. Therefore, management actions against the African citrus psyllid should be concentrated mainly on gardens, private backyards, and orchards where lemon plants are predominant. Lemon trees are very common in private backyards of coastal regions of Portugal and northern Spain where the pest is expanding.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

5. References

Aidoo OF, Tanga CM, Khamis FM, Rasowo BA, Mohamed SA, Badii BK, Salifu D, Sétamou M, Ekesi S, Borgemeister C (2019) Host suitability and feeding preference of the African citrus triozid Trioza erytreae Del Guercio (Hemiptera: Triozidae), natural vector of “Candidatus Liberibacter africanus”. J Appl Entomol 143:262–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/jen.12581

Amorós ME, Neves VP, Rivas F, Buenahora J, Martini X, Stelinski LL, Rossini C (2019) Response of Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae) to volatiles characteristic of preferred citrus host. Arthropod-Plant Inte 13:367–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-018-9651-8

Antolinez CA, Fereres A, Moreno A (2017a) Risk assessment of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum’ transmission by the psyllids Bactericera trigonica and B. tremblayi from Apiaceae crops to potato. Sci Rep 7:4553. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep45534

Antolinez CA, Moreno A, Appezzato-da-Gloria B, Fereres A (2017b) Characterization of the electrical penetration graphs of the psyllid Bactericera trigonica on carrots. Entomol Exp Appl 163(2):127–139. https://doi.org/10.1111/eea.12565

Antwi-Agyakwa AK, Fombong AT, Deletre E, Ekesi S, Yusuf AA, Pirk C, Torto B (2019) Lemon terpenes influence behavior of the African citrus triozid Trioza erytreae (Hemiptera: Triozidae). J Chem Ecol 45:934–945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10886-019-01123-y

Benhadi-Marín J, Fereres A, Pereira JA (2020) A model to predict the expansion of Trioza erytreae throughout the Iberian peninsula using a pest risk analysis approach. Insects 11:576. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects11090576

Bonani JP, Fereres A, Garzo E, Miranda MP, Appezzato-Da-Gloria B, Lopes JRS (2010) Characterization of electrical penetration graphs of the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri, in sweet orange seedlings. Entomol Exp Appl 134:34–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.2009.00937.x

Bove JM (2006) Huanglongbing : a destructive, newly-emerging, century-old disease of citrus. J Plant Pathol 88:7–37. https://doi.org/10.4454/jpp.v88i1.828

Catling HD (1971) The bionomics of the South African citrus psylla. Trioza erytreae (Del Guercio) (Homoptera: Psyllidae) 5. The influence of host plant quality. J Ent Soc Sth Afr 34:381–391

Cocuzza GEM, Alberto U, Hernández-Suárez E, Siverio F, Silvestro SD, Tena A, Carmelo R (2016) A review on Trioza erytreae (African citrus psyllid), now in mainland Europe, and its potential risk as vector of huanglongbing (HLB) in citrus. J Pest Sci 90:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10340-016-0804-1

Collins L, Nissinen A, Pietravalle S, Jauhiainen L (2014) Carrot psyllid (Trioza apicalis) feeding behaviour on carrot and potato: An EPG study. In: Proceedings of the 14th Annual SCRI Zebra Chip Reporting Session. November, Portland, OR, USA. p 717.

Deng X, Huang Z, Zheng Z, Lan Y, Dai F (2019) Field detection and classification of citrus Huanglongbing based onhyperspectral reflectance. Comput Electron Agric 167:105006. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2019.105006

Ebert TA, Backus EA, Shugart HJ, Rogers ME (2018) Behavioural plasticity in probing by Diaphorina citri (Hemiptera: Liviidae): Ingestion from phloem vs. xylem is influenced by leaf age and surface. J Insect Behav 31:119–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10905-018-9666-0

Eigenbrode SD, Ding H, Shiel P, Berger PH (2002) Volatiles from potato plants infected with potato leafroll virus attract and arrest the virus vector, Myzus persicae (Homoptera : Aphididae) Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B-Biological Sciences 269:455–460. https://doi:https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2001.1909

Farnier K, Davies NW, Steinbauer WD (2018) Not led by the nose: volatiles from undamaged Eucalyptus hosts do not influence psyllid orientation. Insects 9:166. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects9040166

Fereres A, Peñaflor MFGV, Favaro CF, Azevedo KEX, Landi CH, Maluta NKP, Bento JMS, Lopes JRS (2016) Tomato infection by whitefly-transmitted circulative and non-circulative viruses induce contrasting changes in plant volatiles and vector behaviour. Viruses. https://doi.org/10.3390/v8080225

Garnier M, Bové JM, Jagoueix-Eveillard S, Cronje CPR, Sanders GM, Korsten L, Le Roux HF (2000) Presence of Candidatus Liberibacter africanus in the Western Cape Province of South Africa. In: da Graça, JV, Lee RF, Yokomi RK (eds.). Proceedings of the 14th Conference of the International Organization of Citrus Virologists, Riverside, CA, USA. pp 369–372.

Garzo E, Soria ML, Gómez-Guillamon ML, Fereres A (2002) Feeding behaviour of Aphis gossypii on resistant accessions of different melon genotypes (Cucumis melo). Phytoparasitica 30:129–140. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02979695

George J, Ammar E-D, Hall DG, Shatters RG, Lapointe SL (2018) Prolonged phloem ingestion by Diaphorina citri nymphs compared to adults is correlated with increased acquisition of citrus greening pathogen. Sci Rep 8:10352. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-018-28442-6

Girma M, Wilde GE, Reese J (1992) Russian Wheat Aphid (Homoptera: Aphididae) feeding behavior on host and nonhost plants. J Econ Entomol 85:395–401. https://doi.org/10.1093/jee/85.2.395

Gottwald TR, da Graça JV, Bassanezi RB (2007) Citrus Huanglongbing: The pathogen and its impact. Online Plant Health Progress 8:1. https://doi.org/10.1094/PHP-2007-0906-01-RV

Kristoffersen L, Larsson MC, Anderbrant O (2008) Functional characteristics of a tiny but specialized olfactory system: olfactory receptor neurons of carrot psyllids (Homoptera: Triozidae). Chem Senses 33:759–769. https://doi.org/10.1093/chemse/bjn034

Magomere T, Obukosia SD, Mutitu E, Ngichabe C, Olubayo F, Shibairo S (2009) PCR detection and distribution of huanglongbing disease and psyllid vectors on citrus varieties with changes in elevation in Kenya. J Biol Sci 9:697–709. https://doi.org/10.3923/jbs.2009.697.709

Mann RS, Ali JG, Hermann SL, Tiwari S, Pelz-Stelinski KS, Alborn HT, Stelinski LL (2012) Induced release of a plant-defense volatile ‘deceptively’attracts insect vectors to plants infected with a bacterial pathogen. PLoS Pathog 8(3):e1002610. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.ppat.1002610

Moran VC (1968) Preliminary observations on the choice of host plants by adults of the citrus psylla, Trioza erytreae (Del Guercio) (Homoptera: Psyllidae). J Ent Soc Sth Afr 31(2):403–410

Noldus LPJJ, Spink AJ, Tegelenbosch RAJ (2001) EthoVision: A versatile video tracking system for automation of behavioral experiments. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput 33(3):398–414. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03195394

Noldus Media Recorder (2013) Retrieved from http://www.noldus.com/human-behavior-research/products/media-recorder-0.

Pearson CC, Shugart HJ, Munyaneza JE, Backus EA (2014) Characterization and correlation of EPG waveforms of Bactericera cockerelli (Hemiptera: Triozidae): variability in waveform appearance in relation to applied signal. Ann Entomol Soc Am 107:650–666. https://doi.org/10.1603/AN13178

Pérez-Otero R, Mansilla JP, del Estal P (2015) Detección de la psila africana de los cítricos, Trioza erytreae (Del Guerci, 1918) (Hemiptera: Psylloidea: Triozidae), en la Península Ibérica. Arquivos Entomolóxicos 13:119–122

Powell G, Tosh CR, Hardie J (2006) Host plant selection by aphids: Behavioral, evolutionary, and applied perspectives. Annu Rev Entomol 51:309–330. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151107

Quintana-González de Chaves M, Teresani GR, Hernández-Suárez E, Bertolini E, Moreno A, Fereres A, Cambra M, Siverio F (2020) Candidatus Liberibacter Solanacearum Is unlikely to be transmitted spontaneously from infected carrot plants to citrus plants by Trioza erytreae. Insects 11(8):514

R Core Team (2018) R: a Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. URL. Version 3.5.1. http://www.R-project.org.

Sandanayaka M, Moreno A, Tooman L, Page-Weir N, Fereres A (2014) Stylet penetration activities linked to the acquisition and inoculation of ‘Candidatus Liberibacter solanacearum’ by its vector tomato potato psyllid. Entomol Exp Appl 151:170–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/eea.12179

Sandanayaka M, Connolly PG, Withers TM (2019) Assessment of tomato potato psyllid Bactericera cockerelli (Hemiptera: Triozidae) food plant range by comparing feeding behaviour to survival of early life stages. Austral Entomol 58:387–394. https://doi.org/10.1111/aen.12322

Sarria E, Cid M, Garzo E, Fereres A (2009) Workbook for automatic parameter calculation of EPG data. Comput Electron Agric 67:35–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2009.02.006

Silva JAA, Hall DG, Gottwald TR, Andrade MS, JrW M, Alessandro RT, Lapointe SL, Andrade EC, Machado MA (2016) Repellency of selected Psidium guajava cultivars to the Asian citrus psyllid, Diaphorina citri. Crop Prot 84:14–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cropro.2016.02.006

Siverio F, Marco-Noales E, Bertolini E, Teresani GR, Peñalver J, Mansilla P, Aguín O, Pérez-Otero R, Abelleira A, Guerra-García JA, Hernández E, Cambra M, Milagros López M (2017) Survey of huanglongbing associated with ‘Candidatus Liberibacter’ species in Spain: analyses of citrus plants and Trioza erytreae. Phytopathol Mediterr 56:98–110

Stockton DG, Pescitelli LE, Ebert TA, Martini X, Stelinski LL (2017) Induced preference improves offspring fitness in a phytopathogen vector. Environ Entomol 46:1090–1097. https://doi.org/10.1093/ee/nvx135

Tjallingii WF (1978) Electronic recording of penetration behaviour by aphids. Entomol Exp Appl 24:721–730. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.1978.tb02836.x

van den Berg ME, Deacon VE (1988) Dispersal of the citrus psylla, Trioza erytreae (Hemiptera: Triozidae), in the absence of its host plants. Phytophylactica 20(4):361–368

van Helden M, Tjallingii WF (1993) Tissue localization of lettuce resistance to the aphid Nasonovia ribisnigri using electrical penetration graphs. Entomol Exp Appl 68:269–278. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1570-7458.1993.tb01713.x

Volpe HXL, Zanardi OZ, Magnani RF, Luvizotto RAG, Esperança V, Freitas Rd, Delfino JY, Mulinari TA, Carvalho RId, Wulff NA, Miranda MPd, Peña L (2020) Behavioral responses of Diaphorina citri to host plant volatiles in multiple-choice olfactometers are affected in interpretable ways by effects of background colors and airflows. PLoS ONE 15:e0235630. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235630

Wenninger EJ, Stelinski LL, Hall DG (2009) Roles of olfactory cues, visual cues, and mating status in orientation of Diaphorina citri Kuwayama (Hemiptera: Psyllidae) to four different host plants. Environ Entomol 38:225–234. https://doi.org/10.1603/022.038.0128

Will T, Kornemann SR, Furch ACU, Fred Tjallingil W, Van Bel AJE (2009) Aphid watery saliva counteracts sieve-tube occlusion: A universal phenomenon? J Experim Biol 212:3305–3312

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. The authors are grateful to the European Union grant, programme H2020 entitled: PRE-HLB: Preventing HLB epidemics for ensuring citrus survival in Europe. H2020-SFS-2018–2 Topic SFS-05–2018-2019–2020—new and emerging risks to plant health (Project nº 817526) as well as to the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT, Portugal) for financial support by national funds FCT/MCTES to CIMO (UIDB/00690/2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.P., A.M., and A.F. conceived the idea, J.B.-M, A.F., and E.G. conducted the experiments, J.B.-M, A.M., and E.G. analysed the data, A.F. and J.A. P. secured funding and supervised the work, and all authors contributed to writing and reviewing the paper. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Handling Editor: Hongbo Jiang.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Benhadi-Marín, J., Garzo, E., Moreno, A. et al. Host plant preference of Trioza erytreae on lemon and bitter orange plants. Arthropod-Plant Interactions 15, 887–896 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-021-09862-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11829-021-09862-0