Abstract

In the middle of the 1990s the interest in Lp(a) vanished after a few badly performed studies almost erased Lp(a) from the map of biological targets. However, since roughly 10 years the interest has begun to grow again mainly for two reasons: first, genetic studies using easily accessible and high-throughput techniques for genotyping of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have allowed large studies in patients with cardiovascular disease and controls to be performed. This strengthened the earlier findings on a copy number variation in the LPA gene and its association with cardiovascular outcomes. Second, new therapies are on the horizon raising strong and justified hope that in a few years drugs will become available which tremendously lower Lp(a) concentrations. This review article should provide an introduction to the genetic determination of Lp(a) concentrations and considerations whether Lp(a) concentrations or genetic variants are important for the prediction of cardiovascular risk.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

An astonishing characteristic of Lp(a) is the more than 1000-fold range of concentrations between individuals from less than 0.1 mg/dL to more than 300 mg/dL [1]. Lp(a) concentrations are not influenced much by age, sex, fasting state, inflammation [2, 3] or lifestyle factors such as diet or physical activity. However, the concentrations are under strict genetic control by the LPA gene locus and here especially by a size polymorphism of apo(a) caused by a variable number of so called kringle IV (K-IV) repeats in the LPA gene [1, 4]. Each of these up to more than 40 repeats has a size of 5.6 kB which results in a highly polymorphic and informative copy number variation (CNV).

The substantial differences in Lp(a) concentrations between individuals are to a large extent genetically determined. Family studies revealed a heritability estimate of Lp(a) concentrations of about 90% [5, 6]. Lp(a) is therefore the lipoprotein with the strongest genetic control. The discovery of the size polymorphism of apo(a) in serum [7] and K‑IV CNV in the LPA gene [4, 8,9,10] resulted in the identification of the LPA gene as the major gene for Lp(a) levels.

Individuals expressing a low number of K‑IV repeats resulting in so-called small apo(a) isoforms (up to 22 K-IV repeats) have on average markedly higher Lp(a) concentrations than individuals carrying only large apo(a) isoforms (more than 22 K-IV repeats) [1].

Genetic regulation of Lp(a) concentrations and risk for CHD

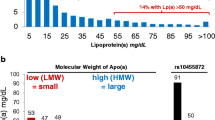

The evidence is quite strong that high Lp(a) concentrations are associated with an increasing risk for coronary heart disease (CHD) [1]. The Copenhagen City Heart Study observed for individuals from a general population with concentrations between 30 and 76 mg/dL (corresponding to the 67th–90th percentile) a 1.6-fold increased risk for incident myocardial infarction compared to individuals with Lp(a) concentrations below 5 mg/dL (corresponding to the lower 22% of the population). This risk increased to 1.90 for persons with Lp(a) concentrations between 77 and 117 mg/dL (90th–95th percentile) and to 2.60 for individuals with Lp(a) concentrations above 117 mg/dL (>95th percentile) ([11]; Fig. 1a). The concentration threshold for an increased risk has been discussed controversially and a European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) consensus statement proposed 50 mg/dL [12]. Most importantly, such a threshold corresponds to the 80th percentile of the concentration distribution in a Caucasian population and means that 20% of the population have probably an increased risk for CVD due to elevated Lp(a) concentrations. From a standpoint of public health relevance, this makes Lp(a) to a very important risk factor for CVD.

Mendelian randomization approach to demonstrate a causal association between Lp(a) concentrations and cardiovascular disease. Panel a shows the association between elevated Lp(a) concentrations and cardiovascular disease (CVD) as shown in the Copenhagen City Heart Study [11]. Panel b shows the association between the number of K‑IV repeats in the LPA gene and Lp(a) concentrations: individuals with small apo(a) isoform have markedly higher median Lp(a) concentrations than individuals with large apo(a) isoforms [23]. Panel c shows the preponderance of small apo(a) isoforms in patients with CVD when compared to controls [27]. Since a low number of K‑IV copies (11–22 copies) is associated with high Lp(a) levels and high Lp(a) levels are associated with CVD, it follows that a low number of K‑IV copies has to be associated with CVD if the association of Lp(a) with CVD is causal. Figure is taken and adapted with permission from reference [29]. Lp(a) lipoprotein(a), apo(a) apolipoprotein(a), LMW low molecular weight, HMW high molecular weight, KIV kringle IV, CVD cardiovascular disease, CHD coronary heart disease, OR odds ratio, 95%CI 95% confidence interval

Besides numerous studies on CHD, during recent years several studies found even a strong association between high Lp(a) concentrations and aortic valve calcification, stroke [13], and stenosis [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21], heart failure [22] as well as peripheral arterial disease [23,24,25]. This makes Lp(a) a risk factor for many CVD endpoints although the strength of the association might differ between the various entities of endpoints.

When a biomarker is changed in diseased patients, the important discussion starts whether this biomarker is a risk factor or a risk marker. If it is a risk factor, this parameter is causally related to disease and it might become an interesting drug target. If it is a biomarker, this parameter might be interesting for diagnostic purposes because it is changed secondarily to the disease (often also called reverse causation), it draws the attention to a disease but it would not make sense to develop drugs which influence that parameter (see recent discussion on this issue in reference [26]). This discussion took place for Lp(a) in the middle of the 1990s and Mendelian randomization studies illustrated in Fig. 1 provided a strong support for causality. Genetic variants that are strongly associated with high Lp(a) concentrations (Fig. 1b) show also an increased risk with CVD (Fig. 1c) which underscores the causal link between high Lp(a) concentrations and CVD. The first time applying such an approach used data on the small apo(a) isoforms determined by the number of K‑IV repeats: small isoforms with up to 22 K-IV repeats (which were called F, B, S1 and S2 in earlier times) were associated with a significantly increased risk for CHD in 6 different populations [27]. A later meta-analysis including 7382 CHD cases and 8514 controls identified a 2.08-fold increased risk for carriers of small apo(a) isoforms [28]. This strong association probably makes Lp(a) the most important genetic risk factor for CVD if we keep the high frequency of small apo(a) isoforms in the population in mind [29].

What methods are available for CVD risk estimation?

Table 1 provides an overview on the methods available and their advantages and disadvantages to investigate the association between Lp(a) concentrations and their genetic determinants with clinical outcomes.

Measurement of Lp(a) concentrations

From a clinical standpoint, the measurement of Lp(a) concentrations is the method of choice to estimate the risk associated with this atherogenic lipoprotein since we assume that we are measuring the biologically active lipoprotein. However, the measurement of Lp(a) is trickier compared to other lipoproteins. A multitude of immunochemical Lp(a) assays have been developed over time and the use of different calibrators and antibodies have resulted in a wide range of Lp(a) measurement values not readily comparable between different assays [30]. The major problem is the repetitive K‑IV structure which causes the size polymorphism with dozens of isoforms. Most of the antibodies used in the various assays are not exactly characterized and are probably directed against the repetitive K‑IV type 2 structure which ranges from 2 to more than 40 repeats. This may result in a measurement bias where serum concentrations of small isoforms, which are usually associated with elevated levels, are underestimated, while serum concentrations of large isoforms, usually associated with low levels, are overestimated. However, we have to distinguish between the relative and the absolute bias of the measurement in relation to the apo(a) isoforms. Thorough comparisons between an isoform-sensitive and an isoform-insensitive assay by Marcovina and colleagues [31] revealed that the relative bias can become quite high with an overestimation of 25–35% in carriers of large isoforms. However, this translates to an absolute bias in most of the samples of a few mg/dL. The relative bias for most of the carriers of small isoforms is around 10% which translates also only to a few mg/dL. However, in the rare cases with up to 16 K-IV repeats, the relative and the absolute bias can become quite pronounced with an underestimation of the concentration and therefore the risk for outcomes. The proportion of these individuals in the general population is rather low: only 1.9% of the population turned out to have such small isoforms when we investigated more than 24,000 individuals with western blot analyses (unpublished data). In summary, when interpreting the data from Marcovina and colleagues [31], we would expect that for most of the individuals this does not really cause a major underestimation or overestimation of the risk. Mainly in the grey zone around the proposed threshold of Lp(a) concentrations, this might become an issue. However, we have to keep in mind that this threshold is also under discussion whether it should be at 30 or 50 mg/dL. Moreover, it has to be added that these data are proven for the assays Marcovina and colleagues have investigated [31]. Whether the absolute and relative biases are similar for other assays needs to be seen and some of the assays have been compared to the assay from Marcovina and colleagues.

Investigation of the K‑IV repeat number by western blot and DNA analysis

The apo(a) isoform size can be best investigated in serum or plasma by western blot using an SDS agarose gel electrophoresis. It has the advantage that only those isoforms will be visible which are indeed expressed. This is one of the peculiarities of Lp(a): although 95% of the subjects are heterozygous on the DNA level, only 50–70% of the individuals show two isoforms in serum. In the remaining 30–50% only a minor fraction is indeed homozygous (which cannot be visualized in the western blot) but the majority of them express only one isoform in serum. The exact number of K‑IV repeats can be measured with a precision of ±1–2 K-IV repeats. However, the method is laborious and only available in a few laboratories. Until today, it is still the best method to be used for Mendelian randomization studies to support causality between Lp(a) and various outcomes (Fig. 1).

Three methods to investigate apo(a) isoforms in terms of number of K‑IV repeats on DNA level are available (Table 1). Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)/southern blotting of genomic DNA [9, 10] is extremely laborious, requires a special DNA preparation to yield high-molecular DNA but allows determination of the number of K‑IV type 2 copies in separated alleles. Both alleles will also be separated by fiber-fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) that allows the number of repeats to be counted under fluorescence microscopy [32]. In contrast to these two methods, quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) is doable in high-throughput [11] but provides the total number (sum) of the K‑IV type 2 copies of the two alleles of the investigated genome. This means that individuals with one short and one large allele and individuals with two medium-sized alleles end up in the same risk category which might result in an underestimation of the risk for the person with one short and one large allele. This is in line with the largest single-center case–control and prospective study up to now describing that individuals in the lower quartile of the sum of copy number in their genome had an adjusted hazard ratio for myocardial infarction of 1.50 compared to those in the highest quartile of copy number. This estimate is lower than that from studies performing the calculations based on the expressed isoforms in western blot with a relative risk of 2.08 [28]. The K‑IV type-2 CNV measured by qPCR explained only 25% of the variability in Lp(a) levels [11], which is also markedly lower than in other studies of European populations using methods such as apo(a) isoforms by western blot or separated alleles by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. These observations might be related to the circumstance that qPCR is not easy to standardize with a relatively high coefficient of variation which makes comparison of results between laboratories difficult.

Based on the peculiarity that roughly 30 to 50% of all individuals express only one apo(a) isoform in serum although they have two isoforms at the DNA level, points to some limitations of the DNA analysis. It raises the question from a clinical standpoint why one should be interested in an isoform that is not expressed. This raises also the question whether it is better to simply consider Lp(a) concentrations instead of the genetic determinants of the concentrations for risk prediction. However, earlier data suggested that Lp(a) from small apo(a) isoforms have a higher atherogenic potential [33]. This finding needs to be further evaluated. Furthermore, certain frequent disease conditions such as chronic kidney disease result in pronounced changes of Lp(a) concentrations. In these patients small apo(a) isoform were demonstrated to be more predictive for CVD risk than Lp(a) concentrations [34, 35] (for review see [1, 36]).

Investigation of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs)

One of the reasons for a revival of the Lp(a) field ten years ago is based on the identification of SNPs that are strongly associated with CHD risk. Clarke and colleagues investigated 27 SNPs in the LPA gene region and observed two SNPs (rs10455872 and rs3798220) to be strongly associated not only with Lp(a) concentrations but also with CHD [37]. These SNPs are easy to analyze in a routine laboratory and might have contributed to their popularity. However, these two SNPs have a minor allele frequency of 7 and 2%, respectively and about 15% of a typical Caucasian population carry at least one minor allele of the two SNPs. They were claimed to identify carriers of small apo(a) isoforms [37]. However, investigations in a large general Caucasian population sample of 5999 subjects revealed that roughly half of all subjects expressing a small apo(a) isoform are not carriers of the minor alleles of one or two of these SNPs [38]. This means that about half of the individuals who have a high risk for CHD based on an expressed small apo(a) isoform will not be detected when only these two SNPs are genotyped. These individuals might get the wrong message when only the SNP result and not also the Lp(a) concentration will be investigated and considered for risk counselling (Fig. 2). Moreover, the situation might be different for various ethnicities. For example, rs3798220 was not found in Africans. Allele frequencies in East and Southeast Asians ranged from 2.9 to 11.6%, and were very low (0.15%) in CAD cases and controls from India. The variant was neither associated with small K‑IV CNV alleles nor elevated Lp(a) concentrations in Asians [39].

In a recent genome-wide association analysis including 13,781 individuals we observed 2001 SNPs in the wider LPA gene region which were significantly associated with Lp(a) concentrations [40]. Many of the SNPs were strongly correlated to each other and an in-depth analysis of the region identified 48 SNPs to be independently associated with Lp(a) concentrations. In addition to this region the SNP in the APOE region that is responsible for the apoE2 allele (rs7412) was also associated with Lp(a) concentrations. In a further step, we made a look-up in the data from the CARDIoGRAMplusC4D consortium. From all 49 genetic variants that were shown to be independently associated with Lp(a) concentrations, 40 were present in summary-level data retrieved from the CARDIoGRAMplusC4D consortium. Seven SNPs were even significantly associated with CAD on a genome-wide scale. This means that a SNP score with more SNPs than rs10455872 and rs3798220 might be better suitable for risk prediction [40].

SNPs in the kringle-IV type 2 region—a journey to a white spot on the genetic map

The K‑IV type 2 is a region that is difficult to resolve by conventional DNA analysis methods. Variants within the K‑IV type 2 region cannot be detected in common sequencing projects, leaving up to 70% of the LPA coding region currently unaddressed. We recently developed an ultra-deep sequencing protocol and an easy-to-use variant analysis pipeline to create a first map of genetic variation in the K‑IV type 2 region. We found dozens of loss-of-function and splice site mutations, as well as >100 partially even common missense variants. This provides novel candidates to explain the large ethnic and individual differences in Lp(a) concentrations [41]. One of these variants is a splice site variant (G4925A) in preferential association with the smaller apo(a) isoforms [42]. It has an exceptionally high carrier frequency of 22.1% in the general population and explains 20.6% of the Lp(a) variance in carriers of small apo(a) isoforms. It reduces Lp(a) concentrations dramatically by more than 30 mg/dL. Accordingly, the odds ratio for CVD was reduced from 1.39 for wildtype carriers of small isoforms to 1.19 in carriers of small isoforms who were additionally positive for G4925A [42]. Functional studies pointed towards a reduction of splicing efficiency highlighting splicing efficiency modulation by antisense oligos or transsplicing [43] as a potential novel Lp(a)-lowering approach [42].

Which approach is now the most suitable for clinical risk assessment?

The measurement of Lp(a) concentrations by a well-performing and standardized assay is usually first choice and sufficient to get an estimate for the expected risk for clinical outcomes. The Lp(a) concentration might reflect best the biologically active lipoprotein. Furthermore, since a protein and not a genetic polymorphism is measured, no genetic counseling is required in most countries.

There is at least some evidence (but we would wish to have more) that two persons who have the same high Lp(a) concentration but the one has a large isoform and the other has a small isoform, that the latter has a higher risk which would mean that the smaller isoform (with fewer K‑IV repeats) might be more atherogenic. Therefore, the measurement of the isoform with western blot might provide a further argument for an increased CVD risk. From all methods that investigate apo(a) genetic polymorphisms, it provides the most comprehensive information and is second to the Lp(a) concentrations very suitable for risk prediction. The advantage can probably be explained by the fact that we see only the isoforms which are indeed expressed in serum or plasma and not those which are available on the DNA level but which are suppressed for whatever reasons.

The measurement of the apo(a) isoforms adds also certain information in acquired diseases which are associated with a secondary increase in Lp(a) concentrations. A typical example is chronic kidney disease: we observed especially in patients treated by hemodialysis that they show an increase in Lp(a) concentrations and this relative increase by the disease is especially observed in patients with large apo(a) isoforms when compared to controls with the same isoform categories [44]. Therefore, the risk for CVD events might be highest especially in those patients with small isoforms (which we and others observed indeed [34, 35, 45]) since their exposure to high Lp(a) concentrations lasted already their entire life. In contrast, many patients with large isoforms might have experienced the increase in Lp(a) only recently with the development of chronic kidney disease and the risk might no longer be sufficiently predictable simply by the Lp(a) concentrations [36].

The use of SNPs for risk estimation will have to find its place in the future. Using the famous two SNPs (rs10455872 and rs3798220) described 10 years ago might be less efficient since too many false negative results might be found as illustrated in Fig. 2 (individuals with small apo(a) isoforms and high Lp(a) concentrations despite the non-mutated variants of these SNPs) [38]. A SNP score with a large and growing package of SNPs might be more informative [40]. Using SNPs or SNP scores for individuals should always be done in combination with the Lp(a) concentrations. The same holds true for apo(a) isoforms for which the Lp(a) concentration has to be known anyway for the laboratory process which requires that roughly the same amount of Lp(a) is put on the SDS agarose gel.

Individual risk assessment versus epidemiological studies

Apo(a) isoform-sensitivity of assays

The use of an apo(a) isoform-sensitive assay might result in an underestimation of the association between Lp(a) concentrations and clinical outcomes. As mentioned above, such assays underestimate serum concentrations of small isoforms, which are usually associated with increased CVD risk and overestimate Lp(a) concentrations of large isoforms which are usually associated with a lower CVD risk. Since small isoforms are overrepresented in CVD patients compared to a control group [27, 28], this phenomenon can result in a dilution of the Lp(a) concentration differences between CVD patients and controls. Therefore, negative studies on the association between Lp(a) concentrations and outcomes should exclude that an isoform-sensitivity of the assay has contributed to these results.

Storage effects on Lp(a) concentrations

Some assays are strongly influenced by the effect of storage conditions. This is especially the case for long-termed stored samples from epidemiological studies. Extreme examples are a nearly linear decrease in Lp(a) immunoreactivity of 46% during 6 months of storage [46] or 75% lower Lp(a) values after 600 days of storage compared to fresh samples [47] in two different studies. We observed with our assay in 310 samples on average only a small decrease of Lp(a) of 4.83% during a 25 months storage period but this was higher for individuals with small isoforms compared to those with large isoforms [48].

An effect of sample storage could also be a reason for negative findings in epidemiological studies which used long-term stored samples und using an assay which is even more strongly influenced by sample storage conditions compared to our assay [46, 47]. Some of the earlier studies which used assays not appropriately performing in stored samples were also included in later meta-analyses and might have contributed to an underestimation of the association between Lp(a) concentrations and cardiovascular disease [13] compared to another large single-center study using one well-validated assay [11].

Samples size in clinical and epidemiological studies

It is a widely observed phenomenon in epidemiology that the first group to report a significant test result (the winner) will also report an effect size much larger than is likely to be seen in subsequent replication studies [49]. This phenomenon of “winner’s curse” is often seen in Lp(a) research which is caused by an underpowered study with a pronounced right-skewed distribution of the Lp(a) concentrations where a large proportion of the population has low concentrations. Since the concentrations of Lp(a) are strongly determined by genetic variants with major effect sizes and less by other conditions, usually large sample sizes are required to prove a statistically significant difference which is not caused by chance findings. As discussed earlier and demonstrated by simulations, small sample sizes can cause any result between a patient and a control group [44] or any correlation between Lp(a) concentrations and another parameter [3] if the sample size is small enough. To avoid these false findings, the sample size has to be large enough and if possible, the results should be controlled for genetic variants such as the apo(a) size polymorphism. And a replication of the findings (as usually expected for genetic epidemiological studies) in a different population is of further advantage.

Conclusions

High Lp(a) concentrations are an important risk factor for cardiovascular disease. There is still some urgent need for a better standardization of Lp(a) assays. However, if an assay is performing well, it is sufficient to use that assay for CVD risk assessment. The measurement of the number of K‑IV repeats can add some information under certain circumstances and has an important role for epidemiological studies and especially Mendelian randomization studies. Other methods to measure the K‑IV repeat number are of academic interest. SNPs will have to find their role probably more as a SNP score and there is currently no major added value to be used beside or instead the measurement of Lp(a) concentrations.

References

Kronenberg F, Utermann G (2013) Lipoprotein(a)—resurrected by genetics. J Intern Med 273:6–30

Langsted A, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG (2014) Lipoprotein(a): fasting and nonfasting levels, inflammation, and cardiovascular risk. Atherosclerosis 234:95–101

Kronenberg F (2014) Lipoprotein(a) in various conditions: To keep a sense of proportions. Atherosclerosis 234:249–251

Utermann G (1989) The mysteries of lipoprotein(a). Science 246:904–910

Lamon-Fava S, Jimenez D, Christian JC, Fabsitz RR, Reed T, Carmelli D, Castelli WP, Ordovas JM, Wilson PWF, Schaefer EJ (1991) The NHLBI Twin Study: heritability of apolipoprotein A‑I and B, and low density lipoprotein subclasses and concordance for lipoprotein(a). Atherosclerosis 91:97–106

Austin MA, Sandholzer C, Selby JV, Newman B, Krauss RM, Utermann G (1992) Lipoprotein(a) in women twins: heritability and relationship to apolipoprotein(a) phenotypes. Am J Hum Genet 51:829–840

Utermann G, Menzel HJ, Kraft HG, Duba HC, Kemmler HG, Seitz C (1987) Lp(a) glycoprotein phenotypes: inheritance and relation to Lp(a)-lipoprotein concentrations in plasma. J Clin Invest 80:458–465

Lackner C, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH (1993) Molecular definition of the extreme size polymorphism in apolipoprotein(a). Hum Mol Genet 2:933–940

Lackner C, Boerwinkle E, Leffert CC, Rahmig T, Hobbs HH (1991) Molecular basis of apolipoprotein (a) isoform size heterogeneity as revealed by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis. J Clin Invest 87:2153–2161

Kraft HG, Köchl S, Menzel HJ, Sandholzer C, Utermann G (1992) The apolipoprotein(a) gene: a transcribed hypervariable locus controlling plasma lipoprotein(a) concentration. Hum Genet 90:220–230

Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Steffensen R, Nordestgaard BG (2009) Genetically elevated lipoprotein(a) and increased risk of myocardial infarction. JAMA 301:2331–2339

Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Ray K, Boren J, Andreotti F, Watts GF, Ginsberg H, Amarenco P, Catapano A, Descamps OS, Fisher E, Kovanen PT, Kuivenhoven JA, Lesnik P, Masana L, Reiner Z, Taskinen MR, Tokgozoglu L, Tybjaerg-Hansen A (2010) Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status. Eur Heart J 31:2844–2853

Erqou S, Kaptoge S, Perry PL, Di AE, Thompson A, White IR, Marcovina SM, Collins R, Thompson SG, Danesh J (2009) Lipoprotein(a) concentration and the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and nonvascular mortality. JAMA 302:412–423

Thanassoulis G, Campbell CY, Owens DS, Smith JG, Smith AV, Peloso GM, Kerr KF, Pechlivanis S, Budoff MJ, Harris TB, Malhotra R, O’Brien KD, Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Allison MA, Aspelund T, Criqui MH, Heckbert SR, Hwang SJ, Liu Y, Sjogren M, van der Pals J, Kalsch H, Muhleisen TW, Nothen MM, Cupples LA, Caslake M, Di AE, Danesh J, Rotter JI, Sigurdsson S, Wong Q, Erbel R, Kathiresan S, Melander O, Gudnason V, O’Donnell CJ, Post WS (2013) Genetic associations with valvular calcification and aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 368:503–512

Kamstrup PR, Tybjaerg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG (2014) Elevated lipoprotein(a) and risk of aortic valve stenosis in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol 63:470–477

Arsenault BJ, Boekholdt SM, Dube MP, Rheaume E, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT, Sandhu MS, Tardif JC (2014) Lipoprotein(a) levels, genotype, and incident aortic valve stenosis: a prospective mendelian randomization study and replication in a case-control cohort. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 7:304–310

Vongpromek R, Bos S, Ten KGJ, Yahya R, Verhoeven AJ, De Feyter PJ, Kronenberg F, van Lennep JE, Sijbrands EJ, Mulder MT (2015) Lipoprotein(a) levels are associated with aortic valve calcification in asymptomatic patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia. J Intern Med 278:166–173

Vuorio A, Watts GF, Kovanen PT (2018) Lipoprotein(a) as a risk factor for calcific aortic valvulopathy in heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis 281:25–30

Capoulade R, Yeang C, Chan KL, Pibarot P, Tsimikas S (2018) Association of Mild to Moderate Aortic Valve Stenosis Progression With Higher Lipoprotein(a) and Oxidized Phospholipid Levels: Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. Jama Cardiol (in press) https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2018.3798

Chen HY, Dufresne L, Burr H, Ambikkumar A, Yasui N, Luk K, Ranatunga DK, Whitmer RA, Lathrop M, Engert JC, Thanassoulis G (2018) Association of LPA variants with aortic stenosis: a large-scale study using diagnostic and procedural codes from electronic health records. JAMA Cardiol 3:18–23

Cairns BJ, Coffey S, Travis RC, Prendergast B, Green J, Engert JC, Lathrop M, Thanassoulis G, Clarke R (2017) A replicated, genome-wide significant association of aortic stenosis with a genetic variant for lipoprotein(a): meta-analysis of published and novel data. Circulation 135:1181–1183

Kamstrup PR, Nordestgaard BG (2016) Elevated lipoprotein(a) levels, LPA risk genotypes, and increased risk of heart failure in the general population. JACC Heart Fail 4:78–87

Laschkolnig A, Kollerits B, Lamina C, Meisinger C, Rantner B, Stadler M, Peters A, Koenig W, Stöckl A, Dähnhardt D, Böger CA, Krämer BK, Fraedrich G, Strauch K, Kronenberg F (2014) Lipoprotein(a) concentrations, apolipoprotein(a) phenotypes and peripheral arterial disease in three independent cohorts. Cardiovasc Res 103:28–36

Gurdasani D, Sjouke B, Tsimikas S, Hovingh GK, Luben RN, Wainwright NW, Pomilla C, Wareham NJ, Khaw KT, Boekholdt SM, Sandhu MS (2012) Lipoprotein(a) and risk of coronary, cerebrovascular, and peripheral artery disease: the EPIC-Norfolk prospective population study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 32:3058–3065

Dieplinger B, Lingenhel A, Baumgartner N, Poelz W, Dieplinger H, Haltmayer M, Kronenberg F, Mueller T (2007) Increased serum lipoprotein(a) concentrations and low molecular weight phenotypes of apolipoprotein(a) are associated with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. Clin Chem 53:1298–1305

Kronenberg F (2016) High-density lipoprotein cholesterol on a roller coaster: where will the ride end? Kidney Int 89:747–749

Sandholzer C, Saha N, Kark JD, Rees A, Jaross W, Dieplinger H, Hoppichler F, Boerwinkle E, Utermann G (1992) Apo(a) isoforms predict risk for coronary heart disease: a study in six populations. Arter Thromb 12:1214–1226

Erqou S, Thompson A, Di AE, Saleheen D, Kaptoge S, Marcovina S, Danesh J (2010) Apolipoprotein(a) isoforms and the risk of vascular disease: systematic review of 40 studies involving 58,000 participants. J Am Coll Cardiol 55:2160–2167

Kronenberg F (2016) Human genetics and the causal role of lipoprotein(a) for various diseases. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 30:87–100

Tate JR, Rifai N, Berg K, Couderc R, Dati F, Kostner GM, Sakurabayashi I, Steinmetz A (1998) International Federation of Clinical Chemistry standardization project for the measurement of lipoprotein(a). Phase I. Evaluation of the analytical performance of lipoprotein(a) assay systems and commercial calibrators. Clin Chem 44:1629–1640

Marcovina SM, Albers JJ, Gabel B, Koschinsky ML, Gaur VP (1995) Effect of the number of apolipoprotein(a) kringle 4 domains on immunochemical measurements of lipoprotein(a). Clin Chem 41:246–255

Erdel M, Hubalek M, Lingenhel A, Kofler K, Duba HC, Utermann G (1999) Counting the repetitive kringle-IV repeats in the gene encoding human apolipoprotein(a) by fibre-FISH. Nat Genet 21:357–358

Kronenberg F, Kronenberg MF, Kiechl S, Trenkwalder E, Santer P, Oberhollenzer F, Egger G, Utermann G, Willeit J (1999) Role of lipoprotein(a) and apolipoprotein(a) phenotype in atherogenesis: prospective results from the Bruneck Study. Circulation 100:1154–1160

Kronenberg F, Neyer U, Lhotta K, Trenkwalder E, Auinger M, Pribasnig A, Meisl T, König P, Dieplinger H (1999) The low molecular weight apo(a) phenotype is an independent predictor for coronary artery disease in hemodialysis patients: a prospective follow-up. J Am Soc Nephrol 10:1027–1036

Longenecker JC, Klag MJ, Marcovina SM, Liu YM, Jaar BG, Powe NR, Fink NE, Levey AS, Coresh J (2005) High lipoprotein(a) levels and small apolipoprotein(a) size prospectively predict cardiovascular events in dialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 16:1794–1802

Kronenberg F (2014) Causes and consequences of lipoprotein(a) abnormalities in kidney disease. Clin Exp Nephrol 18:234–237

Clarke R, Peden JF, Hopewell JC, Kyriakou T, Goel A, Heath SC, Parish S, Barlera S, Franzosi MG, Rust S, Bennett D, Silveira A, Malarstig A, Green FR, Lathrop M, Gigante B, Leander K, de Faire U, Seedorf U, Hamsten A, Collins R, Watkins H, Farrall M (2009) Genetic variants associated with Lp(a) lipoprotein level and coronary disease. N Engl J Med 361:2518–2528

Kronenberg F (2014) Genetic determination of lipoprotein(a) and its association with cardiovascular disease. Convenient does not always mean better. J Intern Med 276:243–247

Khalifa M, Noureen A, Ertelthalner K, Bandegi AR, Delport R, Firdaus WJ, Geethanjali FS, Luthra K, Makemaharn O, Pang RW, Salem AH, Sasaki J, Schiefenhoevel W, Lingenhel A, Kronenberg F, Utermann G, Schmidt K (2015) Lack of association of rs3798220 with small apolipoprotein(a) isoforms and high lipoprotein(a) levels in East and Southeast Asians. Atherosclerosis 242:521–528

Mack S, Coassin S, Rueedi R, Yousri NA, Seppälä I, Gieger C, Schönherr S, Forer L, Erhart G, Marques-Vidal P, Ried JS, Waeber G, Bergmann S, Dähnhardt D, Stöckl A, Raitakari OT, Kähönen M, Peters A, Meitinger T, Strauch K, Kedenko L, Paulweber B, Lehtimäki T, Hunt SC, Vollenweider P, Lamina C, Kronenberg F (2017) A genome-wide association meta-analysis on lipoprotein(a) concentrations adjusted for apolipoprotein(a) isoforms. J Lipid Res 58:1834–1844

Coassin S, Schoenherr S, Weissensteiner H, Erhart G, Forer L, Losso JL, Lamina C, Haun M, Utermann G, Paulweber B, Specht G, Kronenberg F (2019) A comprehensive map of single base polymorphisms in the hypervariable LPA Kringle IV-2 copy number variation region. J Lipid Res 60:186–199

Coassin S, Erhart G, Weissensteiner H, de Eca Guimaraes AM, Lamina C, Schonherr S, Forer L, Haun M, Losso JL, Kottgen A, Schmidt K, Utermann G, Peters A, Gieger C, Strauch K, Finkenstedt A, Bale R, Zoller H, Paulweber B, Eckardt KU, Huttenhofer A, Huber LA, Kronenberg F (2017) A novel but frequent variant in LPA KIV-2 is associated with a pronounced Lp(a) and cardiovascular risk reduction. Eur Heart J 38:1823–1831

Hammond SM, Wood MJ (2011) Genetic therapies for RNA mis-splicing diseases. Trends Genet 27:196–205

Kronenberg F, König P, Neyer U, Auinger M, Pribasnig A, Lang U, Reitinger J, Pinter G, Utermann G, Dieplinger H (1995) Multicenter study of lipoprotein(a) and apolipoprotein(a) phenotypes in patients with end-stage renal disease treated by hemodialysis or continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 6:110–120

Zimmermann J, Herrlinger S, Pruy A, Metzger T, Wanner C (1999) Inflammation enhances cardiovascular risk and mortality in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int 55:648–658

Craig WY, Poulin SE, Forster NR, Neveux LM, Wald NJ, Ledue TB (1992) Effect of sample storage on the assay of lipoprotein(a) by commercially available radial immunodiffusion and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kits. Clin Chem 38:550–553

Desmarais RL, Sarembock IJ, Ayers CR, Vernon SM, Powers ER, Gimple LW (1995) Elevated serum lipoprotein(a) is a risk factor for clinical recurrence after coronary balloon angioplasty. Circulation 91:1403–1409

Kronenberg F, Trenkwalder E, Dieplinger H, Utermann G (1996) Lipoprotein(a) in stored plasma samples and the ravages of time: why epidemiological studies might fail. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 16:1568–1572

Ioannidis JP (2008) Why most discovered true associations are inflated. Epidemiology 19:640–648

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

F. Kronenberg declares to have received speaker honoraria from Kaneka, Miltenyi Biotec and Amgen. He is member of advisory boards from Kaneka and Amgen.

Ethical standards

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the special issue “Lp(a) – Update 2018”

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kronenberg, F. Prediction of cardiovascular risk by Lp(a) concentrations or genetic variants within the LPA gene region. Clin Res Cardiol Suppl 14 (Suppl 1), 5–12 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11789-019-00093-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11789-019-00093-5