Abstract

A substantial proportion of patients investigated for anginal symptoms do not have obstructive coronary artery disease upon diagnostic coronary angiography. These patients are significantly more often female than male and many of them have a dysfunction of the coronary microcirculation as the underlying cause for their symptoms. In this article, we describe gender aspects in clinical conditions with angina despite unobstructed coronary arteries. Moreover, we try to give answers as to why microvascular dysfunction is more prevalent among women than men.

Zusammenfassung

Patienten, die wegen Angina pectoris und Verdacht auf eine stenosierende KHK einer Herzkatheteruntersuchung unterzogen werden, haben häufig keine relevanten Koronarstenosen. Diese Konstellation findet sich häufiger bei Frauen als bei Männern und viele Patienten weisen eine Funktionsstörung der koronaren Mikrozirkulation als Ursache ihrer Beschwerden auf. Dieser Artikel beschreibt Geschlechteraspekte bei Patienten mit Angina pectoris und nicht-stenosierten Koronararterien. Darüber hinaus werden Erklärungsansätze geliefert, wieso eine mikrovaskuläre Funktionsstörung bei Frauen häufiger vorkommt als bei Männern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A substantial proportion of patients investigated for anginal symptoms do not have obstructive coronary artery disease upon diagnostic coronary angiography. These patients are significantly more often female than male and many of them have a dysfunction of the coronary microcirculation as the underlying cause for their symptoms. In this article, we describe gender aspects in clinical conditions with angina despite unobstructed coronary arteries. Moreover, we try to give answers as to why microvascular dysfunction is more prevalent among women than men.

Clinical presentation

Chest pain is one of the most frequent symptoms for seeking medical attention. For the clinician, it is a challenging task to determine the cause of the pain. It is especially important to identify patients in whom the chest pain is of cardiac origin, i.e. angina pectoris, as this may have important consequences for further diagnostic and therapeutic interventions as well as for prognosis.

The description of chest pain associated with obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD) is based on observations in mainly male populations [1, 2]. As a result, the term ‘typical’ angina has evolved to be defined as exertional chest pain, located retrosternally or in the left chest that resolves at rest or after nitroglycerine administration [3]. It has, however, become apparent that women with obstructive CAD often describe their symptoms different from what has been defined as typical. In a Caucasian population (2,676 women and 2,929 men) with chest pain, Zaman et al. [4] found that women significantly more often complained about ‘atypical chest pain’ when compared with men. Furthermore, women with chronic stable angina are more likely than men to have chest pain at rest, during sleep or evoked by mental stress [5] in addition to their exercise-related symptoms. Moreover, women with stable angina often have more intense pain, discomfort in the neck area, disturbed sleep and psychosomatic symptoms such as tiredness, tendency to weep and headache [6, 7], making it challenging to suspect a cardiac origin of their symptoms.

Exercise stress testing

Traditional risk assessment tools for CAD use the patient’s demographics, cardiovascular risk factor profile and symptoms [1, 2]. In addition, results from exercise stress tests have been used to optimize risk stratification (e.g. the Duke Treadmill Score) [8]. However, studies have shown that the electrocardiographic (ECG) treadmill test, one of the most widely utilized CAD risk stratification tools, has a lower sensitivity and specificity in women when compared with men [9]. This results in women with anginal symptoms and a pathologic exercise stress test often undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography without finding significant CAD [10]. Consequently, this has led to the interpretation that women often have a false-positive exercise stress test. However, such findings are entirely compatible with ischemic heart disease caused by disorders of the coronary microcirculation [11], which is more prevalent in women than in men [12].

Clinical conditions

Patients with anginal symptoms and unobstructed coronary arteries represent a heterogeneous group of patients. Clinically, they can be divided into patients with an acute presentation and those with stable symptoms. The former include patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) without culprit lesion such as patients with tako-tsubo-cardiomyopathy, myocarditis or coronary spasm [13], whereas the latter often comprise patients with microvascular angina (cardiac syndrome X), valvular heart disease or cardiac infiltrative diseases, for instance Fabry’s disease [14] (Fig. 1). Generally, a female preponderance among patients with angina despite unobstructed coronary arteries has been described [10, 15]. However, depending on the clinical condition, there are distinct differences between women and men that will be elucidated in the following paragraphs.

ACS without culprit lesion

Studies have shown that approximately 10–30 % of patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome do not have a culprit lesion [15, 16]. Importantly, women with unstable angina, usually in the form of resting angina, represent the largest group of ACS patients without culprit lesion and around 30 % of them have no relevant CAD upon coronary angiography [15]. Coronary spasm, tako-tsubo-cardiomyopathy and myocarditis have been described as explanations for the acute presentation in this group of patients [16–18]. Looking at the gender distribution of these conditions, epicardial spasm as the cause for ACS is equally frequent in women and men [16, 19], whereas patients with myocarditis are more often male than female [18, 20]. In contrast, a clear female preponderance for tako-tsubo-cardiomyopathy has been shown [21]. In a study of 324 German tako-tsubo-cardiomyopathy patients, 9 % were male and 91 % female [21]. Interestingly, the male in comparison with the female patients had significantly more often out-of-hospital cardiac arrest or cardiogenic shock. Moreover, a physical trigger for the acute presentation was more often found in men than in women, which has also been reported in a Japanese study by Kurisu et al. [22].

Stable angina with unobstructed coronary arteries

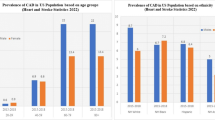

The high use of diagnostic coronary angiography in western countries revealed that a substantial number of patients, mainly women, with stable symptoms suggestive of obstructive CAD actually have no relevant epicardial stenosis [10]. Some authors argued that clinical decision making and referral patterns for diagnostic coronary angiography should be optimized in order to increase the proportion of patients with obstructive disease. However, it may be difficult to improve the selection of patients as suggested because a substantial number of patients with unobstructed coronary arteries, mainly women, have in fact a pathologic non-invasive test indicating the presence of myocardial ischemia. Moreover, we and others [12, 23] have shown that many patients, mainly women, with angina despite unobstructed coronary arteries can have functional abnormalities of the coronary arteries as an explanation for their symptoms. The latter include epicardial dynamic stenoses and coronary microvascular dysfunction. Interestingly, women tend to have microvascular dysfunction more often than men [24] (Fig. 2), whereas men more often have epicardial spasm in the setting of stable angina upon intracoronary provocation testing with acetylcholine [25].

A typical finding during intracoronary acetylcholine provocation testing in a 62-year-old woman with exertional shortness of breath and angina at rest. After i.c. administration of 100 mg acetylcholine (left), the patient reports reproduction of her usual symptoms. The electrocardiogram (ECG) shows ischemic shifts, but there is no relevant epicardial vasoconstriction. After intracoronary administration of nitroglycerine (right), the pathologic findings quickly reverted. (With permission from Ong et al. [29])

Explanations for the clinical findings

In many of the aforementioned conditions, an involvement of the coronary microcirculation has been described. Apart from microvascular angina (cardiac syndrome X), it has been proposed that viral myocarditis [26] as well as tako-tsubo-cardiomyopathy have an underlying microvascular dysfunction [27]. Moreover, it has been shown that many patients with epicardial coronary spasm, especially those with the distal diffuse type of spasm, may have additional microvascular spasm/dysfunction [28], indicating that some forms of epicardial spasm may be an epiphenomenon to underlying disorders of the microcirculation [29]. The fact that patients with coronary microvascular dysfunction are more often women may point towards a different pathophysiology in women compared with men, creating a female phenotype with angina despite unobstructed epicardial arteries. Although the underlying mechanisms are still incompletely understood, there is some evidence to explain these clinical observations.

Coronary anatomy

Although there is little knowledge on cardiovascular anatomy and physiology dissimilarities by gender, it has been shown that the size of a woman’s heart and major blood vessels is smaller than that of men of the same race and age. Moreover, the coronary arteries of women often have a smaller diameter, thinner walls and a more winding course [30, 31], a difference already apparent in early adulthood.

Hormonal differences

Women develop cardiovascular diseases later in life when compared with men, which has been ascribed to the protective effects of oestrogen on the cardiovascular system. Oestrogen has a positive effect on lipid profiles by stimulating high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol production and reverse cholesterol transport [32], which results in decreased low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and increased HDL cholesterol and triglycerides [33]. Oestrogen deficiency is related to decrease in insulin sensitivity and increase in insulin resistance [34]. Moreover, oestrogen exerts a vasodilatory effect on vascular tone by facilitating smooth muscle relaxation. The increased vasodilatory reserve can translate to an anti-ischemic effect [35]. Transdermal 17b-estradiol decreases frequency of chest pain episodes [36] and decreases exercise-induced angina and ST-segment depression [37] in postmenopausal women with microvascular angina. Interestingly, oestrogen’s beneficial effects seem to be gender-dependent, as men do not experience the same improvements in vascular function and coronary blood flow [38]. However, hormone replacement therapy should only be initiated after consultation with a gynaecologist to evaluate the individual pros and cons as well as side effects of such treatment.

Cardiovascular risk factors

The sequelae of the traditional cardiovascular risk factors are well known. However, it has been appreciated only recently that all cardiovascular risk factors can have substantial deleterious effects on the coronary microcirculation leading to vascular damage, enhanced susceptibility to vasoactive stimuli and microvascular rarefaction [39], mainly via enhanced vascular inflammation [40–42]. In this context, it has been shown that women have, on average, higher mean C-reactive protein concentrations compared with men, a gender difference apparent at the time of puberty [43]. Moreover, the relative risk of future cardiovascular events increases with increasing levels of high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, acting synergistically with other risk factors to accelerate ischemic heart disease risk in women [44–46]. Several inflammatory markers, including high-sensitivity C-reactive protein, are related to cardiovascular risk factors such as the cardiometabolic syndrome or type 2 diabetes [42, 47]. It has been shown, for example, that obese women have higher leptin concentrations compared with obese men [48], which can result in a more intense vascular inflammatory response [49].

Treatment approaches

Physicians should be aware of the different clinical conditions responsible for angina despite normal-appearing coronary arteries. Consequently, investigations for the mechanisms of angina should be pursued (e.g. assessment of coronary vasomotor responses using acetylcholine [12] and/or cardiac magnetic resonance imaging). Only with such an approach, appropriate medical treatment can be initiated. However, patients with refractory angina may undergo percutaneous coronary intervention or even coronary artery bypass surgery in the absence of any significant stenosis, as minor lesions are accused to be the cause of the problem (Fig. 3). This not only exposes the patients to unnecessary risks associated with the procedure but may also lead to psychological problems when the patients continue to have chronic pain.

Representative case of a 71-year-old female patient who underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG) in 2002 for obstructive coronary artery disease. Eight years later, coronary angiography was repeatedly performed because of recurrent angina, similar to the angina before CABG. Surprisingly, the arterial bypass of the left internal mammary artery was degenerated (a) and the left anterior descending artery (LAD) did not show any relevant stenosis (b). Intracoronary acetylcholine testing (200 mg) revealed coronary artery spasm in the distal LAD with reproduction of the patient’s symptoms (c). The spasm resolved after intracoronary nitroglycerine administration (d).

If vasomotor abnormalities have been demonstrated, strict control of cardiovascular risk factors should be pursued. In addition, patients should receive drugs to improve endothelial function or to reduce inflammation, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors [50] and statins [51]. Epicardial coronary vasomotor abnormalities should be treated with calcium channel blockers. In patients with a resting heart rate of > 70/min, administration of diltiazem is recommended. If the heart rate is < 70/min, amlodipine should be administered. Nitrates are also recommended for treatment of epicardial vasomotor abnormalities. They should be administered together with calcium channel blockers in order to maximise the therapeutic benefits. Nicorandil can also be used to control chest pain associated with coronary vasospasm or reduced vasodilator capacity in response to exercise [52]. In patients with exertional anginal symptoms and who were found to have microvascular dysfunction by provocative testing, calcium channel blockers and nitrates may be used as first-line therapy. However, the use of nitrates in these patients has shown variable efficacy. Nitrates do not seem to be better than beta-blockers such as atenolol [53]. In some patients, symptom control may only be achieved if medical treatment is complemented with nicorandil or ranolazine [54].

Prognosis and health resource utilisation

Although previous studies in patients with angina and unobstructed coronary arteries have reported a favourable prognosis regarding cardiovascular events during follow-up [55, 56], recent data among larger patient cohorts have shown that this group of patients has a risk of approximately 1–1.5 % per year for adverse cardiovascular events such as myocardial infarction or cardiac death [57–59]. However, estimation of prognosis can be difficult as prognosis in certain subgroups may be different because of the heterogeneity of mechanisms responsible for clinical presentation with angina and unobstructed coronary arteries. Nevertheless, improving the patient’s symptoms should be one of the main goals of the therapy as this has also been shown to improve outcome [60].

Moreover, there is a high morbidity in these patients during follow-up, resulting in frequent medical consultations and consumption of healthcare resources especially in women with angina and unobstructed coronary arteries. Interestingly, the reasons for the high costs of care are due to the presence and persistence of anginal symptoms. In addition, it has been shown that patients with angina and unobstructed coronary arteries require more medication than those with angina due to obstructive coronary artery disease. In fact, the costs of anti-anginal drug therapy were higher for women with non-obstructive CAD as compared to those with obstructive CAD [61]. It is estimated that nearly half of women presenting for a de novo chest pain evaluation will still have angina symptoms at 5-year follow-up [61]. Thus, one can easily envision how high costs of care can be influenced by chest pain symptoms.

Conclusion

Patients with angina despite unobstructed coronary arteries are often women. A dysfunction of the coronary microcirculation is more prevalent in women because of a combination of risk factors, vascular inflammation and hormonal alterations. Although these patients represent an important group of patients, many of them are not properly managed because the mechanisms underlying their discomfort are not properly investigated. Thus, owing to ongoing symptoms, these patients are responsible for a substantial part of healthcare expenditure in western countries. In today’s personalised medicine, metabolomics and proteomics should focus on gender differences in pathway regulations and ways to modify them. If we know more about the underlying mechanisms and about how to investigate them thoroughly but economically, we will not only be able to reduce healthcare costs but may also be able to improve mortality and morbidity.

Disclosures

None.

References

Conroy RM, Pyorala K, Fitzgerald AP, Sans S, Menotti A, De Backer G, DeBacquer D, Ducimetiere P, Jousilahti P, Keil U, Njolstad I, Oganov RG, Thomsen T, Tunstall-Pedoe H, Tverdal A, Wedel H, Whincup P, Wilhelmsen L, Graham IM; SCORE project group (2003) Estimation of ten-year risk of fatal cardiovascular disease in Europe: the SCORE project. Eur Heart J 24:987–1003

Assmann G, Cullen P, Schulte H (2002) Simple scoring scheme for calculating the risk of acute coronary events based on the 10-year follow-up of the prospective cardiovascular Münster (PROCAM) study. Circulation 105:310–315

Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, Buszman P, Camici PG, Crea F, Daly C, De Backer G, Hjemdahl P, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Morais J, Pepper J, Sechtem U, Simoons M, Thygesen K, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Camm J, Dean V, Deckers J, Dickstein K, Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Morais J, Osterspey A, Tamargo J, Zamorano JL (2006) Task Force on the management of stable angina pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: executive summary: the task force on the management of stable angina pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 27:1341–1381

Zaman MJ, Junghans C, Sekhri N, Chen R, Feder GS, Timmis AD, Hemingway H (2008) Presentation of stable angina pectoris among women and South Asian people. CMAJ 179:659–667

Pepine CJ, Abrams J, Marks RG, Morris JJ, Scheidt SS, Handberg E (1994) Characteristics of a contemporary population with angina pectoris. TIDES investigators. Am J Cardiol 74:226–231

D’Antono B, Dupuis G, Fortin C, Arsenault A, Burelle D (2006) Angina symptoms in men and women with stable coronary artery disease and evidence of exercise-induced myocardial perfusion defects. Am Heart J 151:813–819

Billing E, Hjemdahl P, Rehnqvist N (1997) Psychosocial variables in female vs male patients with stable angina pectoris and matched healthy controls. Eur Heart J 18:911–918

Mark DB, Shaw L, Harrell FE Jr, Hlatky MA, Lee KL, Bengtson JR, McCants CB, Califf RM, Pryor DB (1991) Prognostic value of a treadmill exercise score in outpatients with suspected coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med 325:849–853

Kwok Y, Kim C, Grady D, Segal M, Redberg R (1999) Meta-analysis of exercise testing to detect coronary artery disease in women. Am J Cardiol 83:660–666

Patel MR, Peterson ED, Dai D, Brennan JM, Redberg RF, Anderson HV, Brindis RG, Douglas PS (2010) Low diagnostic yield of elective coronary angiography. N Engl J Med 362:886–895

Lanza GA, Crea F (2010) Primary coronary microvascular dysfunction: clinical presentation, pathophysiology, and management. Circulation 121:2317–2325

Ong P, Athanasiadis A, Borgulya G, Mahrholdt H, Kaski JC, Sechtem U (2012) High prevalence of a pathological response to acetylcholine testing in patients with stable angina pectoris and unobstructed coronary arteries. The ACOVA study (Abnormal COronary VAsomotion in patients with stable angina and unobstructed coronary arteries). J Am Coll Cardiol 59:655–662

Kardasz I, De Caterina R (2007) Myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries: a conundrum with multiple aetiologies and variable prognosis: an update. J Intern Med 261:330–348

Yilmaz A, Sechtem U (2012) Angina pectoris in patients with normal coronary angiograms: current pathophysiological concepts and therapeutic options. Heart 98:1020–1029

Hochman JS, Tamis JE, Thompson TD, Weaver WD, White HD, Van de Werf F, Aylward P, Topol EJ, Califf RM (1999) Sex, clinical presentation, and outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes. Global use of strategies to open occluded coronary arteries in acute coronary syndromes IIb investigators. N Engl J Med 341:226–232

Ong P, Athanasiadis A, Hill S, Vogelsberg H, Voehringer M, Sechtem U (2008) Coronary artery spasm as a frequent cause of acute coronary syndrome: the CASPAR (Coronary Artery Spasm in Patients With Acute Coronary Syndrome) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 52:523–527

Deshmukh A, Kumar G, Pant S, Rihal C, Murugiah K, Mehta JL (2012) Prevalence of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in the United States. Am Heart J 164:66–71

Agewall S, Daniel M, Eurenius L, Ekenbäck C, Skeppholm M, Malmqvist K, Hofman-Bang C, Collste O, Frick M, Henareh L, Jernberg T, Tornvall P (2012) Risk factors for myocardial infarction with normal coronary arteries and myocarditis compared with myocardial infarction with coronary artery stenosis. Angiology 63(7):500–503 doi:10.1177/0003319711429560

Wang CH, Kuo LT, Hung MJ et al (2002) Coronary vasospasm as a possible cause of elevated cardiac troponin I in patients with acute coronary syndrome and insignificant coronary artery disease. Am Heart J 144:275–281

Kytö V, Saraste A, Voipio-Pulkki LM, Saukko P (2007) Incidence of fatal myocarditis: a population-based study in Finland. Am J Epidemiol 165:570–574

Schneider B, Athanasiadis A, Stöllberger C, Pistner W, Schwab J, Gottwald U, Schoeller R, Gerecke B, Hoffmann E, Wegner C, Sechtem U (2011) Gender differences in the manifestation of tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.11.027

Kurisu S, Inoue I, Kawagoe T, Ishihara M, Shimatani Y, Nakama Y, Kagawa E, Dai K, Ikenaga H (2010). Presentation of Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy in men and women. Clin Cardiol 33:42–45

Reis SE, Holubkov R, Conrad Smith AJ, Kelsey SF, Sharaf BL, Reichek N, Rogers WJ, Merz CN, Sopko G, Pepine CJ (2001) WISE Investigators. Coronary microvascular dysfunction is highly prevalent in women with chest pain in the absence of coronary artery disease: results from the NHLBI WISE study. Am Heart J 141:735–741

Vermeltfoort IA, Raijmakers PG, Riphagen II, Odekerken DA, Kuijper AF, Zwijnenburg A, Teule GJ (2010) Definitions and incidence of cardiac syndrome X: review and analysis of clinical data. Clin Res Cardiol 99:475–481

Sueda S, Ochi N, Kawada H, Matsuda S, Hayashi Y, Tsuruoka T, Uraoka T (1999) Frequency of provoked coronary vasospasm in patients undergoing coronary arteriography with spasm provocation test of acetylcholine. Am J Cardiol 83:1186–1190

Saraste A, Kytö V, Saraste M, Vuorinen T, Hartiala J, Saukko P (2006) Coronary flow reserve and heart failure in experimental coxsackievirus myocarditis. A transthoracic Doppler echocardiography study. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291:H871–H875

Galiuto L, De Caterina AR, Porfidia A, Paraggio L, Barchetta S, Locorotondo G, Rebuzzi AG, Crea F (2010) Reversible coronary microvascular dysfunction: a common pathogenetic mechanism in Apical Ballooning or Tako-Tsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J 31:1319–1327

Sun H, Mohri M, Shimokawa H, Usui M, Urakami L, Takeshita A (2002) Coronary microvascular spasm causes myocardial ischemia in patients with vasospastic angina. J Am Coll Cardiol 39(5):847–851

Ong P, Athanasiadis A, Mahrholdt H, Borgulya G, Sechtem U, Kaski JC (2012) Increased coronary vasoconstrictor response to acetylcholine in women with chest pain and normal coronary arteriograms (cardiac syndrome X). Clin Res Cardiol 101:673–681

Kitzman DW, Scholz DG, Hagen PT, Ilstrup DM, Edwards WD (1988) Age-related changes in normal human hearts during the first 10 decades of life. Part II (maturity): a quantitative anatomic study of 765 specimens from subjects 20 to 99 years old. Mayo Clin Proc 63:137–146

Paulsen S, Vetner M, Hagerup LM (1975) Relationship between heart weight and the cross sectional area of the coronary ostia. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand A 83:429–432

Knopp RH, Zhu X, Bonet B (1994) Effects of estrogens on lipoprotein metabolism and cardiovascular disease in women. Atherosclerosis 110 (Suppl):S83–S91

The Writing Group for the PEPI Trial (1995) Effects of estrogen or estrogen/progestin regimens on heart disease risk factors in postmenopausal women. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) Trial. JAMA 273:199–208

Walton C, Godsland IF, Proudler AJ, Wynn V, Stevenson JC (1993) The effects of the menopause on insulin sensitivity, secretion and elimination in non-obese, healthy women. Eur J Clin Invest 23:466–473

Hirata K, Shimada K, Watanabe H, Muro T, Yoshiyama M, Takeuchi K, Hozumi T, Yoshikawa J (2001) Modulation of coronary flow velocity reserve by gender, menstrual cycle and hormone replacement therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol 38:1879–1884

Rosano GM, Peters NS, Lefroy D, Lindsay DC, Sarrel PM, Collins P, Poole-Wilson PA (1996) 17-beta-Estradiol therapy lessens angina in postmenopausal women with syndrome X. J Am Coll Cardiol 28:1500–1505

Albertsson PA, Emanuelsson H, Milsom I (1996) Beneficial effect of treatment with transdermal estradiol-17-beta on exercise-induced angina and ST segment depression in syndrome X. Int J Cardiol 54:13–20

Collins P, Rosano GM, Sarrel PM, Ulrich L, Adamopoulos S, Beale CM, McNeill JG, Poole-Wilson PA (1995) 17 beta-Estradiol attenuates acetylcholine-induced coronary arterial constriction in women but not men with coronary heart disease. Circulation 92:24–30

Granger DN, Rodrigues SF, Yildirim A, Senchenkova EY (2010) Microvascular responses to cardiovascular risk factors. Microcirculation 17:192–205

Joshi MS, Tong L, Cook AC, Schanbacher BL, Huang H, Han B, Ayers LW, Bauer JA (2012) Increased myocardial prevalence of C-reactive protein in human coronary heart disease: direct effects on microvessel density and endothelial cell survival. Cardio Vasc Pathol 21:428–435

Teragawa H, Fukuda Y, Matsuda K, Ueda K, Higashi Y, Oshima T, Yoshizumi M, Chayama K (2004) Relation between C reactive protein concentrations and coronary microvascular endothelial function. Heart 90:750–754

Ong P, Sivanathan R, Borgulya G, Bizrah M, Iqbal Y, Andoh J, Gaze D, Kaski JC (2012) Obesity, inflammation and brachial artery flow-mediated dilatation: therapeutic targets in patients with microvascular angina (cardiac syndrome X). Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 26:239–244

Wong ND, Pio J, Valencia R, Thakal G (2001) Distribution of C-reactive protein and its relation to riskfactors and coronary heart disease risk estimation in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) III. Prev Cardiol 4:109–114

Ridker PM, Buring JE, Shih J, Matias M, Hennekens CH (1998) Prospective study of C-reactive protein and the risk of future cardiovascular events among apparently healthy women. Circulation 98:731–733

Ridker PM, Buring JE, Cook NR, Rifai N (2003) C-reactive protein, the metabolic syndrome, and risk of incident cardiovascular events: an 8-year follow-up of 14,719 initially healthy American women. Circulation 107:391–397

Cook NR, Buring JE, Ridker PM (2006) The effect of including C-reactive protein in cardiovascular risk prediction models for women. Ann Intern Med 145(1):21–29

Marroquin OC, Kip KE, Kelley D et al (2004) The metabolic syndrome modifies the cardiovascular risk associated with angiographic coronary artery disease in women: a report from WISE. Circulation 1009:714–721

Kennedy A, Gettys TW, Watson P, Wallace P, Ganaway E, Pan Q, Garvey WT (2009) The metabolic significance of leptin in humans: gender-based differences in relationship to adiposity, insulin sensitivity, and energy expenditure. J ClinEndocrinol Metab 82:1293–1300

De Rosa S, Cirillo P, Pacileo M, Di Palma V, Paglia A, Chiariello M (2009) Leptin stimulated C reactive protein production by human coronary artery endothelial cells. J Vasc Res 46:609–617

Pauly DF, Johnson BD, Anderson RD, Handberg EM, Smith KM, Cooper-DeHoff RM, Sopko G, Sharaf BM, Kelsey SF, Merz CN, Pepine CJ 2011 In women with symptoms of cardiac ischemia, nonobstructive coronary arteries, and microvascular dysfunction, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition is associated with improved microvascular function: A double-blind randomized study from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE). Am Heart J 162:678–684

Yasue H, Mizuno Y, Harada E, Itoh T, Nakagawa H, Nakayama M, Ogawa H, Tayama S, Honda T, Hokimoto S, Ohshima S, Hokamura Y, Kugiyama K, Horie M, Yoshimura M, Harada M, Uemura S, Saito Y, SCAST (Statin and Coronary Artery Spasm Trial) Investigators (2008) Effects of a 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme a reductase inhibitor, fluvastatin, on coronary spasm after withdrawal of calcium-channel blockers. J Am Coll Cardiol 51:1742–1748

Aizawa T, Ogasawara K, Nakamura F, Hirosaka A, Sakuma T, Nagashima K, Kato K (1989) Effect of nicorandil on coronary spasm. Am J Cardiol 63:75J–979

Kaski JC, Valenzuela Garcia LF (2001) Therapeutic options for the management of patients with cardiac syndrome X. Eur Heart J. 22:283–293

Mehta PK, Goykhman P, Thomson LE, Shufelt C, Wei J, Yang Y, Gill E, Minissian M, Shaw LJ, Slomka PJ, Slivka M, Berman DS, BaireyMerz CN (2011) Ranolazine improves angina in women with evidence of myocardial ischemia but no obstructive coronary artery disease. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 4:514–522

Kaski JC, Rosano GM, Collins P, Nihoyannopoulos P, Maseri A, Poole-Wilson PA (1995) Cardiac syndrome X: clinical characteristics and left ventricular function. Long-term follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol 25:807–814

Lamendola P, Lanza GA, Spinelli A, Sgueglia GA, Di Monaco A, Barone L, Sestito A, Crea F (2010) Long-term prognosis of patients with cardiac syndrome X. Int J Cardiol 140:197–199

Gulati M, Cooper-DeHoff RM, McClure C, Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Handberg EM, Zineh I, Kelsey SF, Arnsdorf MF, Black HR, Pepine CJ, Merz CN (2009) Adverse cardiovascular outcomes in women with nonobstructive coronary artery disease: a report from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation Study and the St James Women Take Heart Project. Arch Intern Med 169:843–850

Jespersen L, Hvelplund A, Abildstrøm SZ, Pedersen F, Galatius S, Madsen JK, Jørgensen E, Kelbæk H, Prescott E (2012) Stable angina pectoris with no obstructive coronary artery disease is associated with increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events. Eur Heart J 33:734–744

Humphries KH, Pu A, Gao M, Carere RG, Pilote L (2008) Angina with “normal” coronary arteries: sex differences in outcomes. Am Heart J 155:375–381

Johnson BD, Shaw LJ, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, Kelsey SF, Sopko G, Rogers WJ, Mankad S, Sharaf BL, Bittner V, Bairey Merz CN (2006) Persistent chest pain predicts cardiovascular events in women without obstructive coronary artery disease: results from the NIH-NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischaemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. Eur Heart J 27:1408–1415

Shaw LJ, Merz CN, Pepine CJ, Reis SE, Bittner V, Kip KE, Kelsey SF, Olson M, Johnson BD, Mankad S, Sharaf BL, Rogers WJ, Pohost GM, Sopko G, Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Investigators (2006) The economic burden of angina in women with suspected ischemic heart disease: results from the National Institutes of Health—National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute—sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Circulation 114:894–904

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a supplement sponsored by Lilly Deutschland GmbH and Daiichi Sankyo Deutschland GmbH.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there is no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ong, P., Athanasiadis, A. & Sechtem, U. Gender aspects in patients with angina and unobstructed coronary arteries. Clin Res Cardiol Suppl 8 (Suppl 1), 25–31 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11789-013-0058-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11789-013-0058-x