Abstract

Purpose

Fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) may be equally prevalent, persistent and burdensome in cancer caregivers as in survivors. This systematic review evaluated FCR prevalence, severity, correlates, course, impact and interventions in cancer caregivers.

Methods

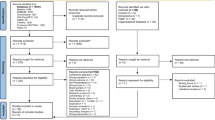

Electronic databases were searched from 1997 to May 2021. Two reviewers identified eligible peer-reviewed qualitative or quantitative studies on FCR in adult caregivers or family members of adult cancer survivors. The risk of bias was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tools for randomised and non-randomised studies and the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool. A narrative synthesis and thematic synthesis occurred on quantitative and qualitative studies, respectively.

Results

Of 2418 papers identified, 70 reports (59 peer-reviewed articles, 11 postgraduate theses) from 63 studies were included. Approximately 50% of caregivers experienced FCR. Younger caregivers and those caring for survivors with worse FCR or overall health reported higher FCR. Most studies found caregivers’ FCR levels were equal to or greater than survivors’. Caregivers’ FCR was persistently elevated but peaked approaching survivor follow-up appointments. Caregivers’ FCR was associated with poorer quality of life in caregivers and survivors. Three studies found couple-based FCR interventions were acceptable, but had limited efficacy.

Conclusions

FCR in caregivers is prevalent, persistent and burdensome. Younger caregivers of survivors with worse overall health or FCR are at the greatest risk. Further research on identifying and treating caregivers’ FCR is required.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Caregiver and survivor FCR are similarly impactful and appear interrelated. Addressing FCR may improve outcomes for both cancer caregivers and survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Lebel S, et al. From normal response to clinical problem: definition and clinical features of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(8):3265–8.

Simard S, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors: a systematic review of quantitative studies. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7(3):300–22.

Smith AB, et al. Spotlight on the Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory (FCRI). Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2020;13:1257–68.

Mellon S, et al. A family-based model to predict fear of recurrence for cancer survivors and their caregivers. Psychooncology. 2007;16(3):214–23.

Mutsaers B, et al. Identifying the key characteristics of clinical fear of cancer recurrence: an international Delphi study. Psychooncology. 2020;29(2):430–6.

Hodges LJ, Humphris GM. Fear of recurrence and psychological distress in head and neck cancer patients and their carers. Psychooncology. 2009;18(8):841–8.

Butow P, et al. A research agenda for fear of cancer recurrence: a Delphi study conducted in Australia. Psychooncology. 2019;28(5):989–96.

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Systematic review: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. York: University of York; 2009.

Shamseer, L., et al., Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015: elaboration and explanation. 2015. 349.

Leske S, et al. A protocol for an updated and expanded systematic mixed studies review of fear of cancer recurrence in families and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer. Syst Rev. 2018;7(1):134.

Lee-Jones C, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence-a literature review and proposed cognitive formulation to explain exacerbation of recurrent fears. Psychooncology. 1997;6(2):95–105.

Rathbone J, et al. Better duplicate detection for systematic reviewers: evaluation of Systematic Review Assistant-Deduplication Module. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):6.

Higgins, J.P.T., et al., The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. 2011. 343: p. d5928.

Kim SY, et al. Testing a tool for assessing the risk of bias for nonrandomized studies showed moderate reliability and promising validity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(4):408–14.

Pluye P, et al. A scoring system for appraising mixed methods research, and concomitantly appraising qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods primary studies in mixed studies reviews. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(4):529–46.

Arai L, et al. Testing methodological developments in the conduct of narrative synthesis: a demonstration review of research on the implementation of smoke alarm interventions. Evid Policy. 2007;3(3):361–83.

Popay, J., et al., Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. ESRC Research Methods Programme. 2006, Lancaster.

Popay J, et al. Developing guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2005;59(Suppl 1):A7.

Rodgers M, et al. Testing methodological guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: effectiveness of interventions to promote smoke alarm ownership and function. Evaluation. 2009;15(1):49–73.

Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45.

Alleyne JL, Gutt C. The lived experience: how men and their female partners cope with the impact of localized prostate cancer. 2008;1458915:238.

Dockery, K.D., Living with uncertainty: the impact on breast cancer survivors and their intimate partners. Diss Abstr Int Sect B: Sci Eng. 2016. 76(7-B(E)): p. No-Specified.

Takeuchi E, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence promotes cancer screening behaviors among family caregivers of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2020;126(8):1784–92.

Northouse LL. Mastectomy patients and the fear of cancer recurrence. 1981;4(3):213–20.

Girgis A, Lambert S, Lecathelinais C. The supportive care needs survey for partners and caregivers of cancer survivors: development and psychometric evaluation. Psychooncology. 2011;20(4):387–93.

Gotay CC, Pagano IS. Assessment of Survivor Concerns (ASC): a newly proposed brief questionnaire. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5(1):15.

Szczesny, E.C., The role of daily partner-directed gratitude, relationship functioning, and fear of recurrence in couples coping with breast cancer. Diss Abstr Int Sect B: Sci Eng. 2015. 76(2-B(E)): p. No-Specified.

Ihrig, A., et al., Online support groups offer low-threshold backing for family and friends of patients with prostate cancer. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018. 28(2): p. e12982.

Vickberg SMJ. The Concerns About Recurrence Scale (CARS): a systematic measure of women’s fears about the possibility of breast cancer recurrence. Ann Behav Med. 2003;25(1):16–24.

Cohee AA, et al. Long-term fear of recurrence in young breast cancer survivors and partners. Psychooncology. 2017;26(1):22–8.

Dempster M, et al. Psychological distress among family carers of oesophageal cancer survivors: the role of illness cognitions and coping. Psychooncology. 2011;20(7):698–705.

Graham, L., et al., Change in psychological distress in longer-term oesophageal cancer carers: are clusters of illness perception change a useful determinant? Psycho-Oncology, 2015.

Soriano EC, et al. Social constraints and fear of recurrence in couples coping with early stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2018;37(9):874–84.

Soriano EC, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence and inhibited disclosure: testing the social-cognitive processing model in couples coping with breast cancer. Ann Behav Med. 2021;55(3):192–202.

Hodgkinson K, et al. Assessing unmet supportive care needs in partners of cancer survivors: the development and evaluation of the Cancer Survivors’ Partners Unmet Needs measure (CaSPUN). Psychooncology. 2007;16(9):805–13.

Hodgkinson K, et al. Life after cancer: couples’ and partners’ psychological adjustment and supportive care needs. Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(4):405–15.

Turner D, et al. Partners and close family members of long-term cancer survivors: health status, psychosocial well-being and unmet supportive care needs. Psychooncology. 2013;22(1):12–9.

Levesque, J.V., M. Gerges, and A. Girgis, The development of an online intervention (Care Assist) to support male caregivers of women with breast cancer: a protocol for a mixed methods study. BMJ Open, 2018. 8(2): p. e019530.

Bamgboje-Ayodele A, et al. The male perspective: a mixed methods study of the impact, unmet needs and challenges of caring for women with breast cancer. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021;39(2):235–51.

van de Wal, M., et al., Fear of cancer recurrence: a significant concern among partners of prostate cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology, 2017.

Simard S, Savard J. Fear of Cancer Recurrence Inventory: development and initial validation of a multidimensional measure of fear of cancer recurrence. Support Care Cancer. 2008;17(3):241.

Lin CR, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence and its impacts on quality of life in family caregivers of patients with head and neck cancers. J Nurs Res (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins). 2016;24(3):240–8.

Lin CR, et al. Psychometric testing of the fear of cancer recurrence inventory-Chinese caregiver version in cancer family caregivers in Taiwan. Psychooncology. 2018;24:140–1.

McManus, L.E., Daily physical activity and fear of recurrence in early stage breast cancer patients and their spouses. Diss Abstr Int Sect B: Sci Eng. 2017. 78(4-B(E)): p. No-Specified.

Perndorfer C, et al. Everyday protective buffering predicts intimacy and fear of cancer recurrence in couples coping with early-stage breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2019;28(2):317–23.

Soriano EC, et al. Does sharing good news buffer fear of bad news? A daily diary study of fear of cancer recurrence in couples approaching the first mammogram post-diagnosis. Psychooncology. 2018;27(11):2581–6.

Soriano EC, et al. Threat sensitivity and fear of cancer recurrence: a daily diary study of reactivity and recovery as patients and spouses face the first mammogram post-diagnosis. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2019;37(2):131–44.

Mehnert A, et al. Fear of progression in breast cancer patients–validation of the short form of the Fear of Progression Questionnaire (FoP-Q-SF). Z Psychosom Med Psychother. 2006;52(3):274–88.

Heinrichs N, et al. Cancer distress reduction with a couple-based skills training: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2012;43(2):239–52.

Zimmermann T, et al. Fear of progression in partners of chronically ill patients. Behav Med. 2011;37(3):95–104.

Muldbücker P, et al. Are women more afraid than men? Fear of recurrence in couples with cancer – predictors and sex-role-specific differences. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2021;39(1):89–104.

Hu X, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in patients with multiple myeloma: prevalence and predictors based on a family model analysis. Psychooncology. 2020;30(2):176–84.

Boehmer U, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence in survivor and caregiver dyads: differences by sexual orientation and how dyad members influence each other. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(5):802–13.

Christie KM, Meyerowitz BE. Partners of breast cancer survivors: research participation and understanding of survivors’ concerns. 2011;3487887:68.

Ellis, A.P., The effects of coping strategies and interactional patterns on individual and dyadic adjustment to prostate cancer. Diss Abstr Int Sect B: Sci Eng. 1998. 59(3-B): p. 1365.

Mellon S, Northouse LL, Weiss LK. A population-based study of the quality of life of cancer survivors and their family caregivers. Cancer Nurs. 2006;29(2):120–33.

Mellon S, Northouse L. Dimensions of family survivorship during the chronic phase of cancer illness. 1999;9827224:210.

Ponto, J.A., Adjustment and growth in ovarian cancer survivors and their spouses. Diss Abstr Int Sect B: Sci Eng. 2009. 69(12-B): p. 7418.

Rowley-Green G, Meyerowitz BE. Sexual intimacy and fear of recurrence from the perspective of partners of breast cancer patients. 2003;1417939:71.

Walker BL. Adjustment of husbands and wives to breast cancer. Cancer Pract. 1997;5(2):92–8.

Humphris GM, et al. Unidimensional scales for fears of cancer recurrence and their psychometric properties: the FCR4 and FCR7. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2018;16(1):30.

Braun SE, et al. Examining fear of cancer recurrence in primary brain tumor patients and their caregivers using the actor-partner interdependence model. Psychooncology. 2021;30(7):1120–8.

Matthews BA. Role and gender differences in cancer-related distress: a comparison of survivor and caregiver self-reports. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30(3):493–9.

Ferrell BR, et al. Family caregiving in cancer pain management. J Palliat Med. 1999;2(2):185–95.

Matthews BA, Baker F, Spillers RL. Family caregivers and indicators of cancer-related distress. Psychol Health Med. 2003;8(1):46–56.

Nidhi V, Basavareddy A. Perception and quality of life in family caregivers of cancer patients. Indian J Palliat Care. 2020;26(4):415–20.

Book K, et al. Distress screening in oncology—evaluation of the Questionnaire on Distress in Cancer Patients—short form (QSC-R10) in a German sample. Psychooncology. 2011;20(3):287–93.

Haun MW, et al. Depression, anxiety and disease-related distress in couples affected by advanced lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2014;86(2):274–80.

Balfe M, et al. The unmet supportive care needs of long-term head and neck cancer caregivers in the extended survivorship period. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25(11–12):1576–86.

Butow PN, et al. Caring for women with ovarian cancer in the last year of life: a longitudinal study of caregiver quality of life, distress and unmet needs. Gynecol Oncol. 2014;132(3):690–7.

Clavarino AM, et al. The needs of cancer patients and their families from rural and remote areas of Queensland. Aust J Rural Health. 2002;10(4):188–95.

Girgis A, et al. Some things change, some things stay the same: a longitudinal analysis of cancer caregivers’ unmet supportive care needs. Psychooncology. 2013;22(7):1557–64.

Haj Mohammad N, et al. Burden of spousal caregivers of stage II and III esophageal cancer survivors 3 years after treatment with curative intent. Support Care Cancer. 2015;23(12):3589–98.

Maguire R, et al. Worry in head and neck cancer caregivers: the role of survivor factors, care-related stressors, and loneliness in predicting fear of recurrence. Nurs Res. 2017;66(4):295–303.

Roth AJ, et al. The Memorial Anxiety Scale for Prostate Cancer. Cancer. 2003;97(11):2910–8.

Chien C-H, et al. Positive and negative affect and prostate cancer-specific anxiety in Taiwanese patients and their partners. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2018;37:1–11.

Zhang, L., et al., Survey on Chinese breast cancer patients’ husbands toward breast conserving surgery. J BUON. 2014. 19(4): p. 887–894.

Wu LM, et al. Longitudinal dyadic associations of fear of cancer recurrence and the impact of treatment in prostate cancer patients and their spouses. Acta Oncol. 2019;58(5):708–14.

Xu W, Wang J, Schoebi D. The role of daily couple communication in the relationship between illness representation and fear of cancer recurrence in breast cancer survivors and their spouses. Psychooncology. 2019;28(6):1301–7.

Kim Y, et al. Dyadic effects of fear of recurrence on the quality of life of cancer survivors and their caregivers. Qual Life Res. 2012;21(3):517–25.

Janz N, et al. Worry about recurrence in a multi-ethnic population of breast cancer survivors and their partners. Support Care Cancer. 2016;24(11):4669–78.

Northouse LL, et al. The concerns of patients and spouses after the diagnosis of colon cancer: a qualitative analysis. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 1999;26(1):8–17.

Thewes B, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic literature review of self-report measures. Psychooncology. 2012;21(6):571–87.

Mellon S, Northouse LL. Family survivorship and quality of life following a cancer diagnosis. Res Nurs Health. 2001;24(6):446–59.

Northouse LL, et al. A family-based program of care for women with recurrent breast cancer and their family members. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29(10):1411–9.

la Cour K, Ledderer L, Hansen HP. Storytelling as part of cancer rehabilitation to support cancer patients and their relatives. 2016;34(6):460–76.

Gerhardt, S., et al., From bystander to enlisted carer – a qualitative study of the experiences of caregivers of patients attending follow-up after curative treatment for cancers in the pancreas, duodenum and bile duct. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2020. 44: p. 101717.

McCorry NK, et al. Adjusting to life after esophagectomy: the experience of survivors and carers. Qual Health Res. 2009;19(10):1485–94.

Cavers, D.G., Understanding the supportive care needs of glioma patients and their relatives: a qualitative longitudinal study. 2010. 10091452.

Tan JH, Sharpe L, Russell H. The impact of ovarian cancer on individuals and their caregivers: a qualitative analysis. Psychooncology. 2020;30(2):212–20.

Vivar, C.G., Again: an account of demoralisation in patients and families experiencing recurrence of cancer. 2007. U588528: p. 1.

Lethborg CE, Kissane D, Burns WI. ‘It’s not the easy part’: the experience of significant others of women with early stage breast cancer, at treatment completion. Soc Work Health Care. 2003;37(1):63–85.

Catania, A.M., C. Sammut Scerri, and G.J. Catania, Men’s experience of their partners’ breast cancer diagnosis, breast surgery and oncological treatment. J Clin Nurs. 2019. 28(9–10): p. 1899–1910.

O’Callaghan C, et al. ‘What is this active surveillance thing?’ Men’s and partners’ reactions to treatment decision making for prostate cancer when active surveillance is the recommended treatment option. Psychooncology. 2014;23(12):1391–8.

Keesing S, Rosenwax L, McNamara B. A call to action: the need for improved service coordination during early survivorship for women with breast cancer and partners. Women Health. 2019;59(4):406–19.

Lebel, S., et al., Towards the validation of a new, blended theoretical model of fear of cancer recurrence. 2018. 27(11): p. 2594–2601.

Fardell JE, et al. Fear of cancer recurrence: a theoretical review and novel cognitive processing formulation. J Cancer Surviv. 2016;10(4):663–73.

Smith AB, et al. Medical, demographic and psychological correlates of fear of cancer recurrence (FCR) morbidity in breast, colorectal and melanoma cancer survivors with probable clinically significant FCR seeking psychological treatment through the ConquerFear study. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26(12):4207–16.

van de Wal, M., et al., Does fear of cancer recurrence differ between cancer types? A study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Psycho-Oncology, 2016: p. 772–778.

Liu J, Butow P, Beith J. Systematic review of interventions by non-mental health specialists for managing fear of cancer recurrence in adult cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27(11):4055–67.

Lisy K, et al. Identifying the most prevalent unmet needs of cancer survivors in Australia: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2019;15(5):e68–78.

Tauber NM, et al. Effect of psychological intervention on fear of cancer recurrence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(31):2899–915.

Taylor, J., et al., Access to support for Australian cancer caregivers: in-depth qualitative interviews exploring barriers and preferences for support. J Psychosoc Oncol Res Pract. 2021. 3(2).

Tutelman PR, Heathcote LC. Fear of cancer recurrence in childhood cancer survivors: a developmental perspective from infancy to young adulthood. Psychooncology. 2020;29(11):1959–67.

Hodgkinson K, et al. After cancer: the unmet supportive care needs of survivors and their partners. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25(4):89–104.

Persson E, Severinsson E, Hellström A. Spouses’ perceptions of and reactions to living with a partner who has undergone surgery for rectal cancer resulting in a stoma. Cancer Nurs. 2004;27(1):85–91.

Ream, E., et al., Understanding the support needs of family members of people undergoing chemotherapy: a longitudinal qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021. 50: p. 101861.

Shands ME, et al. Core concerns of couples living with early stage breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(12):1055–64.

Yeo W, et al. Psychosocial impact of breast cancer surgeries in Chinese patients and their spouses. Psychooncology. 2004;13(2):132–9.

Funding

This research was undertaken with funding for people support from the Cancer Institute of New South Wales (ABS, VSW, AG).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Afaf Girgis, Allan ‘Ben’ Smith, Sylvie Lambert and Stuart Leske conceived the study. Stuart Leske developed the selection criteria, search strategy, data extraction templates and risk of bias assessment. Allan ‘Ben’ Smith, Afaf Girgis, Sylvie Lambert, Jani Lamarche and Sophie Lebel provided expertise on FCR. Verena S. Wu, Allan ‘Ben’ Smith, Jani Lamarche and Sophie Lebel conducted the data extraction, risk of bias assessment and data analysis. Allan ‘Ben’ Smith, Afaf Girgis and Verena S. Wu drafted the article. Stuart Leske, Sylvie Lambert, Jani Lamarche and Sophie Lebel critically revised and provided feedback on the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This is a systematic review, and therefore, no ethical approval is required. Consent to participate is not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Methodology of included studies

ID | Author (year) | Theoretical framework | Study design | Study setting | N caregivers | Type of cancer of care recipient | Sampling strategy | Data collection method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Alleyne & Gutt (2008) [21] | Neuman’s systems model | Qualitative | Peer support group | 5 | Prostate | Purposive | Semi-structured interviews |

2 | Balfe et al. (2016) [69] | NR | Cross-sectional | NR | 197 | Head and neck | NR | Questionnaire |

3 | Bamgboje-Ayodele et al. (2021) [39] | Yardley’s person-based approach | Mixed methods | Support organisations | 89 | Breast | Convenience | Survey Interview |

4 | Boehmer et al. (2016) [53] | NR | Cross-sectional | Community-based | 167 | Breast | Non-probability | Telephone survey |

5 | Braun et al. (2021) [62] | Actor-partner interdependence model | Cross-sectional | Cancer centre | 52 | Brain | NR | Survey |

6 | Butow et al. (2014) [70] | NR | Longitudinal | Treatment centres Cancer registries | 99 | Ovarian | NR | Questionnaire |

7 | Catania et al. (2019) [93] | Interpretive phenomenological approach | Qualitative | NR | 8 | Breast | NR | Interview |

8 | Cavers (2010) [89] | Grounded theory | Qualitative | Hospital | 24 | Glioma | Purposive | Semi-structured interviews |

9 | Chien et al. (2018) [76] | NR | Longitudinal | Medical centre | 48 | Prostate | Purposive | Questionnaire |

10 | Christie & Meyerowitz (2011) [54] | NR | Longitudinal | Hospital | 153 | Breast | Convenience | Questionnaire |

11 | Clavarino et al. (2002) [71] | NR | Mixed methods | Clinic Patient’s residence | 19 | Mixed | Purposive | Questionnaire and structured interview |

12 | Cohee et al. (2017) [30] | Social cognitive processing theory | Cross-sectional | University Cancer institute | 222 | Breast | Purposive | Questionnaire |

13 | Dempster et al. (2011) [31] | Self-regulatory model | Cross-sectional | Support group database | 382 | Oesophageal | Convenience | Questionnaire |

14 | Dockery (2016) [22] | Social constructionist | Qualitative | Skype | 5 | Breast | Purposive Convenience | Interview |

15 | Ellis (1998) [55] | Emotional approach coping Demand/withdraw interaction | Longitudinal | Medical facilities | 30 | Prostate | NR | Questionnaire |

16 | Gerhardt et al. (2020) [87] | NR | Qualitative | Home | 10 | Pancreative, duodenum, bile duct | Convenience | Interview |

17 | Girgis et al. (2013) [72] | Lazarus and Folkman’s stress and coping | Longitudinal | Participant homes | 547 | Mixed | NR | Survey |

18 | Graham et al. (2015) [32] | Leventhal’s common sense model | Longitudinal | Participant homes | 171 | Oesophageal | NR | Questionnaire |

19 | Haj Mohammad et al. (2015) [73] | NR | Cross-sectional | Medical centre | 47 | Oesophageal | NR | Questionnaire |

20 | Haun et al. (2014) [68] | NR | Cross-sectional | Medical centre | 54 | Lung | NR | Questionnaire |

21 | Heinrichs et al. (2012) [49] | Cognitive behavioural theory | Randomised controlled study | Hospital | 72 | Breast | NR | Questionnaire |

22 | Hodges & Humphris (2009) [6] | NR | Longitudinal | Multi-centre | 101 | Head and neck | NR | Survey |

23 | Hodgkinson et al. (2007) [35] | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital | 212 | Mixed | NR | Questionnaire |

24 | Hodgkinson et al. (2007) [36] | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital | 154 | Mixed | NR | Questionnaire |

25 | Hodgkinson et al. (2007) [105] | NR | Qualitative | Database | 8 | Mixed | Convenience | Semi-structured interviews |

26 | Hu et al. (2020) [52] | Family survivorship model | Cross-sectional | Cancer centre | 127 | Multiple myeloma | Convenience | Questionnaire |

27 | Ihrig et al. (2018) [28] | NR | Cross-sectional | Participant home | 83 | Prostate | NR | Survey |

28 | O'Callaghan et al. (2014) [94] | NR | Qualitative | Cancer centre | 14 | Prostate | Purposive | Semi-structured interviews |

29 | Janz et al. (2016) [81] | Modified stress and appraisal framework | Cross-sectional | Cancer registry | 510 | Breast | NR | Survey |

30 | Keesing et al. (2019) [95] | NR | Mixed methods | Community | 8 | Breast | Purposive | Interview |

31 | Kim et al. (2012) [80] | NR | Cross-sectional | Cancer registry | 455 | Mixed | NR | Survey |

32 | la Cour et al. (2016) [86] | Narrative theory Social practice theory | Qualitative | Medieval castle | 10 | Mixed | NR | Interview |

33 | Lethborg et al. (2003) [92] | Systems theory | Qualitative | Participant homes | 8 | Breast | Purposive | Interview |

34 | Lin et al. (2016) [42] | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital | 250 | Head and neck | Convenience | Questionnaire |

35 | Lin et al. (2018) [43] | NR | Cross-sectional | Medical centre | 300 | Head and neck | Convenience | Questionnaire |

36 | Maguire (2017) [74] | Common sense model | Qualitative | Hospital | 180 | Head and neck | Purposive | Interview |

37A | Matthews (2003) [63] | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital cancer registries Online network | 135 | Mixed | Convenience | Questionnaire |

37B | Matthews et al. (2003) [65] | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital cancer registries Online network | 135 | Mixed | Convenience | Questionnaire |

38 | McCorry et al. (2009) [88] | Wainwright, Donovan Kacadas, Cramer and Blazeby (2007) | Qualitative | Oesophageal patients’ association | 10 | Oesophageal | Purposive | Focus group |

39 | McManus (2017) [44] | Actor-partner independence model | Longitudinal | Community cancer centre | 71 | Breast | NR | Daily diary Accelerometer |

40A | Mellon et al. (2007) [4] | Family stress coping framework | Cross-sectional | Participant home Other selected by the family | 123 | Mixed | Stratified random | Questionnaire |

40B | Mellon & Northouse (2001) [84] | Family survivorship model | Cross-sectional | Participant home | 123 | Mixed | Stratified random | Questionnaire |

40C | Mellon et al. (2006) [56] | Family survivorship model | Cross-sectional | Participant home | 123 | Mixed | Stratified random | Questionnaire |

40D | Mellon & Northouse (1999) [57] | Resiliency model | Mixed methods | Cancer institute | 123 | Mixed | Stratified random | Survey Interview |

41 | Muldbücker et al. (2021) [51] | NR | Cross-sectional | Participant home | 188 | Mixed | NR | Questionnaire |

42 | Nidhi & Basavareddy (2020) [66] | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital | 148 | NR | Random | Questionnaire |

43 | Northouse et al. (1999) [82] | Stress and coping model | Cross-sectional | Oncology clinics | 30 | Colorectal | Convenience | Interview |

44 | Northouse et al. (2002) [85] | Family stress coping framework | Randomised controlled study | Participant home | 73 | Breast | Stratified random | Questionnaire |

45 | Perndorfer et al. (2019) [45] | The relationship intimacy model | Longitudinal | Participant home | 69 | Breast | NR | Daily diary |

46 | Persson et al. (2004) [106] | NR | Qualitative | Outpatient clinic | 9 | Colorectal | NR | Focus group |

47 | Ponto (2009) [58] | Resiliency model | Cross-sectional | Cancer organisation | 32 | Ovarian | Snowball | Survey |

48 | Ream et al. (2021) [107] | BR | Qualitative | Hospital, telephone, private homes, carers’ workplace | 25 | Mixed | Purposive | Interview |

49 | Rowley-Green & Meyerowitz (2003) [59] | NR | Longitudinal | Medical centre | 171 | Breast | NR | Questionnaire |

50 | Shands et al. (2006) [108] | NR | Qualitative | Home intervention | 29 | Breast | Consecutive | Tape recording of the intervention session |

51A | Soriano et al. (2021) [34] | Social-cognitive processing model | Longitudinal | Participant home | 79 | Breast | NR | Survey |

51B | Soriano et al. (2019) [47] | Cancer anxiety theories | Longitudinal | Participant homes | 58 | Breast | NR | Daily diary Survey |

51C | Soriano et al. (2018) [33] | Social-cognitive processing model | Study 1: cross-sectional Study 2: longitudinal | Participant homes | Study 1: 46 Study 2: 72 | Breast | NR | Study 1: survey Study 2: daily diary |

51D | Soriano et al. (2018) [46] | NR | Longitudinal | Participant homes | 57 | Breast | NR | Survey |

52 | Szczesny (2015) [27] | Generalised mediation framework | Longitudinal | Cancer centre | 44 | Breast | NR | Diary Survey |

53 | Takeuchi et al. (2020) [23] | NR | Longitudinal | Participant homes | 813 | Mixed | Snowball | Questionnaires |

54 | Tan et al. (2020) [90] | NR | Qualitative | Online | 78 | Ovarian | NR | Open-ended survey |

55 | Turner et al. (2013) [37] | NR | Cross-sectional | Cancer registry | 257 | Mixed | NR | Survey |

56 | van de Wal et al. (2017) [40] | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital database | 168 | Prostate | NR | Survey |

57 | Vivar (2007) [91] | Grounded theory | Qualitative | Hospital | 14 | Mixed | Purposive | Interview |

58 | Walker (1997) [60] | NR | Cross-sectional | Support group Treatment centre Hospital | 58 | Breast | NR | Survey |

59 | Wu et al. (2019) [78] | Social cognitive theory Common sense model | Longitudinal | Participant home | 62 | Prostate | NR | Questionnaire |

60 | Xu et al. (2019) [79] | Cognitive behavioural model of FCR Intimacy process model | Longitudinal | Participant home | 54 | Breast | NR | Questionnaire Daily diary |

61 | Yeo et al. (2004) [109] | NR | Cross-sectional | NR | 23 | Breast | NR | Questionnaire |

62 | Zhang et al. (2014) [77] | NR | Cross-sectional | Hospital | 1468 | Breast | NR | Questionnaire |

63 | Zimmermann et al. (2011) [50] | NR | Cross-sectional | Rehabilitation clinic | 119 | Breast | NR | Survey |

Appendix 2. Risk of bias assessment

Appraisal of non-randomised controlled studies (RoBANS) (n = 49)

Appraisal | Low risk, N (%) | High risk/unclear, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

Selection of participants | 27 (55) | 22 (45) |

Confounding variables | 36 (73) | 13 (27) |

Measurement of exposure | 27 (55) | 22 (45) |

Incomplete outcome data | 35 (71) | 14 (29) |

Selective outcome reporting | 42 (86) | 7 (14) |

Appraisal of qualitative and mixed-methods studies (MMAT) (n = 20)

Appraisal | Yes, N (%) | No/unclear, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

Qualitative (n = 20) | ||

Are the sources of qualitative data relevant to address the research question/objective? | 20 (100) | – |

Is the process for analysing qualitative data relevant to address the research question/objective? | 20 (100) | – |

Is appropriate consideration given to how findings relate to the context? | 13 (65) | 7 (35) |

Is appropriate consideration given to how findings relate to researchers’ influence? | 6 (30) | 13 (65) |

Quantitative (non-randomised) (n = 1) | ||

Are participants (organisations) recruited in a way that minimises selection bias? | 1 (100) | – |

Are measurements appropriate (clear origin, or validity known, or standard instrument, and absence of contamination between groups) regarding the exposure/intervention and outcomes? | 1 (100) | – |

In the groups being compared, are the participants comparable, or do researchers take into account (control for) the difference between these groups? | NA | – |

Are there complete outcome data, and, when applicable, an acceptable response rate, or an acceptable follow-up rate for cohort studies? | – | 1 (100) |

Quantitative (descriptive) (n = 2) | ||

Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the quantitative research question? | 2 (100) | – |

Is the sample representative of the population under study? | 2 (100) | – |

Are measurements appropriate (clear origin, or validity known, or standard instrument?) | 2 (100) | – |

Is there an acceptable response rate? | 2 (100) | – |

Mixed methods (n = 3) | ||

Is the mixed-methods research design relevant to address the research questions? | 3 (100) | – |

Is the integration of qualitative and quantitative data relevant to address the research question? | 3 (100) | – |

Is appropriate consideration given to the limitations associated with this integration? | 2 (67) | 1 (33) |

Appraisal of randomised controlled studies (Cochrane Collaboration) (n = 2)

Appraisal | Low, N (%) | High/unclear, N (%) |

|---|---|---|

Selection bias | ||

Random sequence generation | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

Allocation concealment | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

Performance bias | ||

Blinding of participants and personnel | – | 2 (100) |

Detection bias | ||

Blinding of outcome assessment | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

Attrition bias | ||

Incomplete outcome data | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

Reporting bias | ||

Selective reporting | 1 (50) | 1 (50) |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, A.‘., Wu, V.S., Lambert, S. et al. A systematic mixed studies review of fear of cancer recurrence in families and caregivers of adults diagnosed with cancer. J Cancer Surviv 16, 1184–1219 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01109-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-021-01109-4