Abstract

Purpose

Active social engagement, both on and offline, is widely recognized as an important buffer against the negative effects of cancer-related stress. Nevertheless, studies show that social stigma can lead to a decrease in available social support following cancer diagnosis. This study examines whether Facebook friends provide continuous, health-promoting social support to breast cancer patients following transitions in care.

Methods

To examine support provided to breast cancer patients, we hand-coded 21,291 status updates and wall posts with respect to both post content and support exchange. We then use descriptive statistics, pairwise t tests, and temporal maps to show whether posts received more likes, comments, or unique commenters following breast cancer diagnosis and the post content that was most likely to garner positive responses from Facebook friends.

Results

Results showed an initial increase across all three support metrics (likes, comments, and unique commenters) after cancer diagnosis but that all three metrics decrease steadily over time. Results also revealed significant decreases in the average number of comments and number of commenters following transition off cancer treatment.

Conclusions

Taken together, our results reveal that while support is available through Facebook, support may be sporadic, characterized by limited engagement and low cost. There is also limited support available through Facebook to weather the stress of transition off cancer treatment.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Facebook is an important feature in people’s lives, particularly among the demographic most impacted by breast cancer. Our results suggest that social media can be useful in accessing support but should be used with caution.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

U.S. Breast Cancer Statistics | Breastcancer.org. In: Breastcancer.org [Internet]. 13 Feb 2019 [cited 23 Sep 2019]. Available: https://www.breastcancer.org/symptoms/understand_bc/statistics

Burgess C, Cornelius V, Love S, Graham J, Richards M, Ramirez A. Depression and anxiety in women with early breast cancer: five year observational cohort study. BMJ. 2005;330:702.

Palesh O, Butler LD, Koopman C, Giese-Davis J, Carlson R, Spiegel D. Stress history and breast cancer recurrence. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63:233–9.

Spiegel D. Psychosocial aspects of breast cancer treatment. Semin Oncol. 1997;24:S1–36–47.

Bloom JR. The relationship of social support and health. Soc Sci Med. 1990;30:635–7.

Gurung RAR, Sarason BR, Sarason IG. Personal characteristics, relationship quality, and social support perceptions and behavior in young adult romantic relationships. Pers Relat. 1997:319–39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.1997.tb00149.x.

Uchino BN, Bowen K, Carlisle M, Birmingham W. Psychological pathways linking social support to health outcomes: a visit with the “ghosts” of research past, present, and future. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:949–57.

Mikal JP, Rice RE, Abeyta A, DeVilbiss J. Transition, stress and computer-mediated social support. Comput Hum Behav. 2013; Available: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S074756321200341X.

Uchino BN. Social support and physical health: understanding the health consequences of relationships: Yale University Press; 2004.

Uchino BN. Social support and health: a review of physiological processes potentially underlying links to disease outcomes. J Behav Med. 2006;29:377–87.

Pope Z, Lee JE, Zeng N, Lee HY, Gao Z. Feasibility of smartphone application and social media intervention on breast cancer survivors’ health outcomes. Transl Behav Med. 2019;9:11–22.

Rodgers S, Chen Q. Internet community group participation: psychosocial benefits for women with breast cancer. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2005;10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2005.tb00268.x.

Moon T-J, Chih M-Y, Shah DV, Yoo W, Gustafson DH. Breast cancer survivors’ contribution to psychosocial adjustment of newly diagnosed breast cancer patients in a computer-mediated social support group. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 2017. pp. 486–514. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699016687724

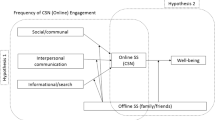

Namkoong K, Shah DV, Gustafson DH. Offline social relationships and online cancer communication: effects of social and family support on online social network building. Health Commun. 2017;32:1422–9.

Berkman LF, Glass T, Brissette I, Seeman TE. From social integration to health: Durkheim in the new millennium. Soc Sci Med. 2000;51:843–57.

Durkheim E. Suicide: a study in sociology (JA Spaulding & G. Simpson, trans.). Glencoe: Free Press (Original work published 1897); 1951.

Durkheim E. Suicide: a study in sociology: Routledge; 2005.

Simmel G. Conflict and the web of group affiliations: Simon and Schuster; 2010.

Simmel G. Georg Simmel on individuality and social forms: University of Chicago Press; 2011.

Lazarus RS. Folkman S, Stress, appraisal, and coping: Springer Publishing Company; 1984.

Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull. 1985;98:310–57.

Thoits PA. Social support as coping assistance. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1986:416–23. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-006x.54.4.416.

Cohen S. Psychosocial models of the role of social support in the etiology of physical disease. Health Psychol. 1988;7:269–97.

Bolger N, Zuckerman A, Kessler RC. Invisible support and adjustment to stress. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:953–61.

Kroenke CH, Kwan ML, Neugut AI, Ergas IJ, Wright JD, Caan BJ, et al. Social networks, social support mechanisms, and quality of life after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;139:515–27.

Kroenke CH, Quesenberry C, Kwan ML, Sweeney C, Castillo A, Caan BJ. Social networks, social support, and burden in relationships, and mortality after breast cancer diagnosis in the Life After Breast Cancer Epidemiology (LACE) Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:261–71.

Michael YL, Berkman LF, Colditz GA, Holmes MD, Kawachi I. Social networks and health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a prospective study. J Psychosom Res. 2002;52:285–93.

McDonough MH, Sabiston CM, Wrosch C. Predicting changes in posttraumatic growth and subjective well-being among breast cancer survivors: the role of social support and stress. Psychooncology. 2014;23:114–20.

Fong AJ, Scarapicchia TMF, McDonough MH, Wrosch C, Sabiston CM. Changes in social support predict emotional well-being in breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2017;26:664–71.

Helgeson VS, Cohen S. Social support and adjustment to cancer: reconciling descriptive, correlational, and intervention research. Health Psychol. 1996;15:135–48.

Wortman CB. Social support and the cancer patient. Conceptual and methodologic issues. Cancer. 1984;53:2339–62.

Perrin A, Jiang J. About a quarter of US adults say they are “almost constantly” online. Pew Research Center. 2018;14.

Fox S, Duggan M, Others. Pew internet and American life project. Health online. 2013;2013.

Khvorostianov N, Elias N, Nimrod G. “Without it I am nothing”: the Internet in the lives of older immigrants. New Media Soc. 2012;14:583–99.

Rice RE, Hagen I. Young adults’ perpetual contact, social connectivity, and social control through the internet and mobile phones. Ann Int Commun Assoc. 2010;34:3–39.

Rainie L, Wellman B. Networked: the new operating system: Cambridge and; 2012.

Wellman B, Haase AQ, Witte J, Hampton K. Does the Internet increase, decrease, or supplement social capital?: social networks, participation, and community commitment. Am Behav Sci. 2001;45:436–55.

Malik SH, Coulson N. The male experience of infertility: a thematic analysis of an online infertility support group bulletin board. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2008;26:18–30.

Rains SA, Keating DM. The social dimension of blogging about health: health blogging, social support, and well-being. Commun Monogr. 2011:511–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2011.618142.

Mikal JP, Grace K. Against abstinence-only education abroad: viewing Internet use during study abroad as a possible experience enhancement. Journal of Studies in International. 2012; Available: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/1028315311423108.

Walther JB, Boyd S. Attraction to computer-mediated social support. Communication technology and society: Audience adoption and uses. 2002;153188 Available: https://msu.edu/~jwalther/docs/support.html.

Attai DJ, Cowher MS, Al-Hamadani M, Schoger JM, Staley AC, Landercasper J. Twitter social media is an effective tool for breast cancer patient education and support: patient-reported outcomes by survey. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17:e188.

Chee W, Lee Y, Im E-O, Chee E, Tsai H-M, Nishigaki M, et al. A culturally tailored internet cancer support group for Asian American breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled pilot intervention study. J Telemed Telecare. 2017;23:618–26.

Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “friends:” social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2007;12:1143–68.

Best P, Manktelow R, Taylor B. Online communication, social media and adolescent wellbeing: a systematic narrative review. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;41:27–36.

Lin LY, Sidani JE, Shensa A, Radovic A, Miller E, Colditz JB, et al. Association between social media use and depression among US young adults. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33:323–31.

Kross E, Verduyn P, Demiralp E, Park J, Lee DS, Lin N, et al. Facebook use predicts declines in subjective well-being in young adults. PLoS One. 2013;8:e69841.

Primack BA, Shensa A, Escobar-Viera CG, Barrett EL, Sidani JE, Colditz JB, et al. Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: a nationally-representative study among U.S. young adults. Comput Human Behav. 2017;69:1–9.

Mehdizadeh S. Self-presentation 2.0: narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2010;13:357–64.

Ryan T, Xenos S. Who uses Facebook? An investigation into the relationship between the big five, shyness, narcissism, loneliness, and Facebook usage. Comput Human Behav. 2011;27:1658–64.

Junco R. The relationship between frequency of Facebook use, participation in Facebook activities, and student engagement. Comput Educ. 2012:162–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2011.08.004.

Stollak MJ, Vandenberg A, Burklund A, Weiss S. Getting social: the impact of social networking usage on grades among college students. Proceedings from ASBBS annual conference. 2011. pp. 859–865.

Mikal JP, Grande SW, Beckstrand M. Organizing Facebook data into quantifiable social support metrics: a coding scheme to evaluate support exchanges among breast cancer patients (preprint). J Med Internet Res. 2018. https://doi.org/10.2196/12880.

Dworkin SL. Sample size policy for qualitative studies using in-depth interviews. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41:1319–20.

Zhang R. The stress-buffering effect of self-disclosure on Facebook: an examination of stressful life events, social support, and mental health among college students. Comput Hum Behav. 2017:527–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.043.

Neuling SJ, Winefield HR. Social support and recovery after surgery for breast cancer: frequency and correlates of supportive behaviours by family, friends and surgeon. Soc Sci Med. 1988;27:385–92.

Dizon DS, Graham D, Thompson MA, Johnson LJ, Johnston C, Fisch MJ, et al. Practical guidance: the use of social media in oncology practice. J Oncol Pract. 2012:e114–24. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2012.000610.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the following individuals for their assistance in carefully coding the data for evidence of support: Abby Beczkalo, Tori Scanlan, and Aarushi Sarkari.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research involving human subjects

Research procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Minnesota IRB. Approval number: MODCR00000494.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mikal, J.P., Beckstrand, M.J., Parks, E. et al. Online social support among breast cancer patients: longitudinal changes to Facebook use following breast cancer diagnosis and transition off therapy. J Cancer Surviv 14, 322–330 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00847-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-019-00847-w