Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to assess the use of non-conventional medicine (NCM) in a representative sample of French patients 2 years after cancer diagnosis.

Methods

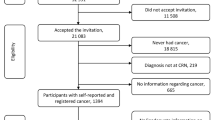

The study was based on data obtained in the VICAN survey (2012) on a representative sample of 4349 patients 2 years after cancer diagnosis. Self-reported data were collected at telephone interviews with patients. The questionnaire addressed the various types of non-conventional treatments used at the time of the survey.

Results

Among the participants, 16.4% reported that they used NCM, and 45.3% of this group had not used NCM before cancer diagnosis (new NCM users). Commonly, NCMs used were homeopathy (64.0%), acupuncture (22.1%), osteopathy (15.1%), herbal medicine (8.1%), diets (7.3%) and energy therapies (5.8%). NCM use was found to be significantly associated with younger age, female gender and a higher education level. Previous NCM use was significantly associated with having a managerial occupation and an expected 5-year survival rate ≥80% at diagnosis; recent NCM use was associated with cancer progression since diagnosis, impaired quality of life and higher pain reports.

Conclusion

This is the first study on NCM use 2 years after cancer diagnosis in France. In nearly half of the NCM users, cancer diagnosis was one of the main factors which incited patients to use NCM. Apart from the NCM users’ socioeconomic profile, the present results show that impaired health was a decisive factor: opting for unconventional approaches was therefore a pragmatic response to needs which conventional medicine fails to meet during the course of the disease.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Better information of patients and caregivers is needed to allow access to these therapies to a larger population of survivors.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Expanding horizons of healthcare: five-year strategic plan 2001–2005. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and National Institutes of Health, Editor. 2000.

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/integrative-health#types. Accessed 10 Jan 2017.

Horneber M, Bueschel G, Less D, et al. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Integr Cancer Ther. 2012;11(3):187–203.

Adler SR. Complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer. Med Anthropol Q. 1999;13(2):214–22.

Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Leedham B, et al. Quality of life in long-term, disease-free survivors of breast cancer: a follow-up study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(1):39–49.

Hunter D, Oates R, Gawthrop J, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use and disclosure amongst Australian radiotherapy patients. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22(6):1571–8.

Hyodo I, Amano N, Eguchi K, et al. Nationwide survey on complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients in Japan. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(12):2645–54.

Molassiotis A, Fernadez-Ortega P, Pud D, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients: a European survey. Ann Oncol. 2005;16(4):655–63.

Pedersen CG, Christensen S, Jensen AB, et al. Prevalence, socio-demographic and clinical predictors of post-diagnostic utilisation of different types of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a nationwide cohort of Danish women treated for primary breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(18):3172–81.

Baum M, Cassileth BR, Daniel R, et al. The role of complementary and alternative medicine in the management of early breast cancer: recommendations of the European Society of Mastology (EUSOMA). Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(12):1711–4.

Deng GE, Rausch SM, Jones LW, et al. Complementary therapies and integrative medicine in lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143(5 Suppl):e420S–36S. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2364.

Simon L, Prebay D, Beretz A, et al. Complementary and alternative medicines taken by cancer patients. Bull Cancer. 2007;94(5):483–8.

Trager-Maury S, Tournigand C, Maindrault-Goebel F, et al. Use of complementary medicine by cancer patients in a French oncology department. Bull Cancer. 2007;94(11):1017–25.

Huiart L, Bouhnik AD, Rey D, et al. Complementary or alternative medicine as possible determinant of decreased persistence to aromatase inhibitor therapy among older women with non-metastatic breast cancer. Plos One. 2013;8(12):e81677.

Thomas-Schoemann A, Alexandre J, Mongaret C, et al. Use of antioxidant and other complementary medicine by patients treated by antitumor chemotherapy: a prospective study. Bull Cancer. 2011;98(6):645–53.

http://www.e-cancer.fr/Professionnels-de-sante/Les-chiffres-du-cancer-en-France/Epidemiologie-des-cancers. Accessed 10 Jan 2017.

Bouhnik AD, Bendiane MK, Cortaredona, et al. The labour market, psychosocial outcomes and health conditions in cancer survivors: protocol for a nationwide longitudinal survey 2 and 5 years after cancer diagnosis (the VICAN survey). BMJ Open. 2015;5(3):e005971.

Burdine JN, Felix MR, Abel AL, et al. The SF-12 as a population health measure: an exploratory examination of potential for application. Health Serv Res. 2000;35(4):885–904.

Groenvold M, Klee MC, Sprangers MA, et al. Validation of the EORTC QLQ-C30 quality of life questionnaire through combined qualitative and quantitative assessment of patient-observer agreement. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50(4):441–50.

Portenoy R. Development and testing of a neuropathic pain screening questionnaire: ID Pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(8):1555–65.

Bouhassira D, Attal N, Alchaar H, et al. Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain. 2005;114(1–2):29–36.

Tuppin P, de Roquefeuil, Weill A, et al. French national health insurance information system and the permanent beneficiaries sample. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2010;58(4):286–90.

Horner MJ, Ries LAG, Krapcho M, et al. SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2006. July 2009. https://seer.cancer.gov/archive/csr/1975_2006/#contents. Accessed 10 Jan 2017.

Lanoë JL, Makdessi-Reynaud Y. L’état de santé en France en 2003: santé perçue, morbidité déclarée et recours aux soins à travers l’enquête décennale santé. Etudes et. 2005;436:1–12.

Bouhnik AD, Préau M, Schlitz MA, et al. Unsafe sex with casual partners and quality of life among HIV-infected gay men: evidence from a large representative sample of outpatients attending French hospitals (ANRS-EN12-VESPA). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42(5):597–603.

Le Corroller-Soriano AG, Bouhnik AD, Preau M, et al. Does cancer survivors’ health-related quality of life depend on cancer type? Findings from a large French national sample 2 years after cancer diagnosis. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2011;20(1):132–40.

Preau M, Marcellin F, Carrieri MP, et al. Health-related quality of life in French people living with HIV in 2003: results from the national ANRS-EN12-VESPA Study. AIDS. 2007;21 Suppl 1:S19–27.

Maskarinec G, Gotay CC, Tatsumura Y, et al. Perceived cancer causes: use of complementary and alternative therapy. Cancer Pract. 2001;9(4):183–90.

Richardson MA, Sanders T, Palmer JL, et al. Complementary/alternative medicine use in a comprehensive cancer center and the implications for oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(13):2505–14.

Navo MA, Phan J, Vaughan C, et al. An assessment of the utilization of complementary and alternative medication in women with gynecologic or breast malignancies. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(4):671–77.

Morris KT, Johnson N, Homer L, Walts D. A comparison of complementary therapy use between breast cancer patients and patients with other primary tumor sites. Am J Surg. 2000;179:407–11.

Bauml JM, Langer CJ, Evans T, et al. Does perceived control predict complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among patients with lung cancer? A cross-sectional survey. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2465–72.

Bauml JM, Chokshi S, Schapira MM. Do attitudes and beliefs regarding complementary and alternative medicine impact its use among patients with cancer? A Cross-Sectional Survey Cancer. 2015;121(14):2431–8.

Edwards GV, Aherne NJ, Horsley PJ, et al. Prevalence of complementary and alternative therapy use by cancer patients undergoing radiation therapy. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(4):346–53.

Chrystal K, Allan S, Forgeson G, et al. The use of complementary/alternative medicine by cancer patients in a New Zealand regional cancer treatment centre. N Z Med J. 2003;116(1168):U296.

Crocetti E, Crotti N, Feltrin A, et al. The use of complementary therapies by breast cancer patients attending conventional treatment. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34(3):324–8.

Smith PJ, Clavarino A, Long J, et al. Why do some cancer patients receiving chemotherapy choose to take complementary and alternative medicines and what are the risks? Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2014;10(1):1–10.

Kim SG, Park EC, Park JH, et al. Initiation and discontinuation of complementary therapy among cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(33):5267–74.

Burstein HJ, Gelber S, Guadagnoli E, et al. Use of alternative medicine by women with early-stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(22):1733–9.

Carlsson M, Arman M, Backman M, et al. Perceived quality of life and coping for Swedish women with breast cancer who choose complementary medicine. Cancer Nurs. 2001;24(5):395–401.

Boon H, Stewart M, Kennard MA, et al. Use of complementary/alternative medicine by breast cancer survivors in Ontario: prevalence and perceptions. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(13):2515–21.

Cohen P, Sarradon-Eck A, Schmitz O, et al. Cancer et pluralisme thérapeutique: Enquête auprès des malades et des institutions médicales en France, Belgique et Suisse. Paris: L’Harmattan; 2016.

Bury M. Chronic illness as biographical disruption. Sociol Healt Ill. 1982;4(2):167–82.

Astin JA: Why patients use alternative medicine: results of a national study. JAMA,1998;279(19): 1548–53.

Clarke TC, Black LI, Stussman BJ et al.: Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. National Health Statistices Reports, 2015 (79) https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr079.pdf. Accessed 10 Jan 2017.

Chan JM, Elkin EP, Silva SJ, et al. Total and specific complementary and alternative medicine use in a large cohort of men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2005;66(6):1223–8.

Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280(18):1569–75.

Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(4):246–52.

Ernst E. Prevalence of use of complementary/alternative medicine: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(2):252–7.

Kelner M, Wellman B. Health care and consumer choice: medical and alternative therapies. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45(2):203–12.

Kersnik J. Predictive characteristics of users of alternative medicine. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 2000;130(11):390–4.

Kessler RC, Davis RB, Foster DF, et al. Long-term trends in the use of complementary and alternative medical therapies in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2001;135(4):262–8.

Lee MM, Lin SS, Wrensch MR, et al. Alternative therapies used by women with breast cancer in four ethnic populations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(1):42–7.

Elziere P: Des médecines dites naturelles. Sciences Sociales et Santé, 1986;IV(2): 39–74.

Laplantine F, Rabeyron PL: Les médecines parallèles, ed. Q. Sais-J. 1987.

Balneaves LG, Truant TL, Kelly M, et al. Bridging the gap: decision-making processes of women with breast cancer using complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). Support Care Cancer. 2007;15(8):973–83.

Baider L, Andritsch E, Uziely B, et al. Effects of age on coping and psychological distress in women diagnosed with breast cancer: review of literature and analysis of two different geographical settings. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;46(1):5–16.

Bartman AJ, Roberto KA. Coping strategies of middle-aged and older women who have undergone a mastectomy. J Appl Gerontol. 1996;15(3):376–86.

Gozum S, Tezel A, Koc K. Complementary alternative treatments used by patients with cancer in eastern Turkey. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26(3):230–6.

Cassileth BR. Unorthodox cancer medicine. Cancer Invest. 1986;4(6):591–8.

Hack TF, Degner, Dyck DG. Relationship between preferences for decisional control and illness information among women with breast cancer: a quantitative and qualitative analysis. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(2):279–89.

Holland JC. Why patients seek unproven cancer remedies: a psychological perspective. CA Cancer J Clin. 1982;32(1):10–4.

McGregor KJ, Peay ER. The choice of alternative therapy for health care: testingsome propositions. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(9):1317–27.

Montbriand MJ. Abandoning biomedicine for alternate therapies: oncology patients’ stories. Cancer Nurs. 1998;21(1):36–45.

Sollner W, Maislinger S, De Vries A, et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients is not associated with perceived distress or poor compliance with standard treatment but with active coping behavior. Cancer. 2000;89(4):873–80.

Truant T, Bottorff JL. Decision making related to complementary therapies: a process of regaining control. Patient Educ Couns. 1999;38(2):131–42.

Yates PM, Beadle G, Clavarino A, et al. Patients with terminal cancer who use alternative therapies: their beliefs and practices. Sociol Health Illn. 1993;15(2):199–216.

Zaloznik AJ. Unproven (unorthodox) cancer treatments: a guide for healthcare professionals. Cancer Pract. 1994;2(1):19–24.

Risberg T, Lund E, Wist E, et al. Cancer patients use of nonproven therapy: a 5-year follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):6–12.

Vincent C, Furnham A. Why do patients turn to complementary medicine? An empirical study. Br J Clin Psychol. 1996;35(1):37–48.

Begot AC. Médecines parallèles et cancer: Une étude sociologique. Paris: L’Harmattan; 2010.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the National Institute of Cancer (INCa), “Contrat de recherche et développement no. 05-2011.” The authors thank Dr. Jessica Blanc for revising the English manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The methods used were approved by three national ethics commissions: the CCTIRS (registration number 11-143), the ISP (registration number C11-63) and the CNIL (registration number 911290).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sarradon-Eck, A., Bouhnik, AD., Rey, D. et al. Use of non-conventional medicine two years after cancer diagnosis in France: evidence from the VICAN survey. J Cancer Surviv 11, 421–430 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0599-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-017-0599-y