Abstract

Florets of Avena fatua (wild oat) did not germinate at temperatures from 5 to 35 °C, nor did caryopses at 5 and above 15 °C. Smoke–water (SW) was found to partly or substantially induce dormant florets and caryopses to germinate at temperatures from 10 to 25 °C, whereby almost all caryopses germinated at 15 and 20 °C. When florets were dry-stored at 25 °C for 4 months, their dormancy, and that of florets was markedly or completely, respectively, removed at 20 °C. Floret and caryopsis SW demand decreased with time of dry storage. Paclobutrazol, a gibberellin biosynthesis inhibitor, completely antagonized the stimulatory effect of SW on germination of caryopses. Gibberellic acid (GA3) reversed inhibition caused by paclobutrazol applied alone or in combination with SW. SW enhanced α- and β-amylase activities in caryopses before radicle protrusion. SW increased α-amylase activity and reduced starch content more effectively in intact caryopses than in embryoless ones. SW enhanced β-tubulin accumulation and the transition from G1 to S and also from S to G2 phases before radicle protrusion. The results presented indicate that florets are more dormant than caryopses and less sensitive to SW at incubation temperatures from 20 °C. Germination induction of dormant Avena fatua caryopses by SW required gibberellin biosynthesis. SW induction of dormant caryopsis germination involves mobilization of starch and cell cycle activation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fire plays an important role in germination and growth of plants in many parts of the world. In 1990 De Lange and Boucher (1990), two South African researchers, identified smoke as the key agent in stimulating germination of a threatened fynbos species Audouinia capitata. The smoke derived from burning plants and an aqueous smoke extract are known to stimulate the release of seed dormancy and germination of 1335 species, such as arable weeds and crop plants, from 120 families in fire- and non-fire-prone ecosystems (Jefferson et al. 2014). Little is known about the influence of smoke–water (SW) on the physiology of weed seeds. We used caryopses and florets of Avena fatua, an important weed distributed worldwide, as a model on which to study dormancy to better understand the state of dormancy and to develop new strategies for controlling the weed. Dormant caryopses can be induced to germinate by a variety of factors, e.g. dry storage (Foley 1994; Kępczyński et al. 2013), gibberellins (Adkins et al. 1986; Kępczyński et al. 2006, 2013), plant-derived smoke (Adkins and Peters 2001; Kępczyński et al. 2006) and karrikinolide (3-methyl-2H-furo[2,3-c]pyran-2-one, KAR1) (Daws et al. 2007; Stevens et al. 2007; Kępczyński et al. 2010, 2013), a compound identified in smoke (Flematti et al. 2004; Van Staden et al. 2004).

KAR1 was demonstrated to require ethylene action (Kępczyński and Van Staden 2012) and gibberellin biosynthesis to stimulate germination of A. fatua dormant caryopses (Kępczyński et al. 2013). KAR1 -mediated Avena fatua caryopsis dormancy release is associated with control of the abscisic acid content, cell cycle, metabolic activity and homeostasis between reactive oxygen species and antioxidants in the embryo (Kępczyński et al. 2013; Cembrowska-Lech et al. 2015; Cembrowska-Lech and Kępczyński 2016). Germination of seeds of some plant species may be stimulated by SW and not by KAR1; however KAR1 but not SW stimulates germination in others (Stevens et al. 2007; Downes et al. 2010). There are also species seed germination of which was enhanced by KAR1 and inhibited by smoke. The stimulatory effect of smoke, although mainly attributed to KAR1, can be also related to other karrikins, e.g. KAR2 and KAR3 and/or glyceronitrile, found in smoke, which act as germination stimulators (Flematti et al. 2009, 2011). Inhibitory effect of smoke or an effect lower than that produced by KAR1 can be associated with the presence of some inhibitors, e.g. 3,4,5-trimethylfuran-2(5H)-one in smoke (Pošta et al. 2013).

In contrast to the knowledge on KAR1 involvement in dormancy release, that of smoke is much less known. There are no data with which to compare the response of dry-stored A. fatua florets, and seeds from florets which were dry-stored for different periods of time, to SW. The literature contains scant information only on the interaction between smoke and endogenous gibberellins; seeds of dicot such as Lactuca sativa (Van Staden et al. 1995) and Nicotiana attenuata (Schwachtje and Baldwin 2004) have been studied only. Moreover, effects of SW on α-amylase activity and starch degradation in intact and embryoless caryopses were not compared. Likewise, effects of SW on DNA synthesis and β-tubulin content before radicle protrusion have not been checked.

Consequently, this study was aimed to examine the role of smoke in germination of dormant Avena fatua caryopses. To address this aim, effects of SW on germination of dormant florets and caryopses were followed (1) at various temperatures, and (2) after various periods of floret dry storage. It was also of interest to find out whether the effect of SW on germination of dormant caryopses is associated with biosynthesis of gibberellins, and whether effects on α-amylase and β-amylase activity, DNA replication and β-tubulin content appear prior to radicle protrusion through the coleorhiza. Effect of SW on α-amylase activity and starch content in caryopses and embryoless caryopses was also examined. Also, isoenzymes of α-amylase in untreated and SW-treated caryopses were analyzed.

Materials and methods

Plant material

Avena fatua L. (wild oat) spikelets were collected on July 21, 2010, during the time of their natural dispersal, in the vicinity of Szczecin (Poland). The spikelets contained 2–3 florets covered with glumes. Each floret was a single caryopsis (fruit) covered by the lemma and palea (Simpson 2007). After collection, the florets were dried at room temperature for 7 days to a constant moisture content (ca. 11%) and then stored at −20 °C until required. The experiments involved both florets and caryopses.

Preparation of smoke–water (SW)

SW was generated by burning 100 g of dry grass leaves in a 3-L metal drum. The smoke was bubbled through distilled water (100 mL) in a glass jar for 45 min (Baxter et al. 1994). This smoke extract was filtered through filter paper (Whatman No. 1) and was used as the stock solution. Different concentrations of SW were prepared by diluting the stock solution with distilled water.

Moisture content and dry weight determination

Dry weight (DW) of caryopses, 25 in three replicates, was determined gravimetrically on fully dried (105 °C for 24 h) specimens. The water content (WC) is expressed relative to the fresh weight (FW) to represent the percentage of water in the total mass, and is calculated as WC = [(FW − DW)/FW] × 100.

Germination tests

Primary dormant florets or caryopses (25 in each of three replicates) were incubated in darkness in Petri dishes (ø 60 mm) on one layer of filter paper (Whatman No. 1) moistened with 1.5 mL of distilled water or various SW dilutions.

In experiment 1, florets or caryopses were incubated in the presence of distilled water or SW (1:10,000, 1:1000, 1:500, 1:100 v/v) in darkness at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 °C for 5 days.

In experiment 2, dormant florets were stored dry in the open air under ambient relative humidity for up to 4 months in darkness at 25 °C to break their dormancy. After 2, 4, 8 and 12 weeks of dry storage, both florets and caryopses (from dry-stored florets) were incubated in darkness at 20 °C in the presence of SW (1:50,000, 1:30,000, 1:10,000, 1:1000 v/v) for 5 days.

In experiment 3, dormant caryopses were preincubated in the presence of SW (1:1000 v/v) alone or in combination with paclobutrazol (PAC) (10−4 M) at 20 °C in darkness for 5 days. Thereafter, the caryopses were rinsed once with 100 mL of distilled water and transferred to new Petri dishes containing GA3 (10−5 M) solution. The caryopses were incubated in the same condition for 5 days.

In all the experiments, counting was performed every day up to day 5 of germination. All manipulations were performed under a green safe light at 0.5 µmol m−2 s−1 which did not affect germination. Florets and caryopses were regarded as germinated when the radicle protruded through the coleorhiza. In experiments 1 and 2, Timson’s index was calculated by summing the progressive total of daily cumulative germination percentage over 5 days (Timson 1965).

α-Amylase (EC 3.2.1.1) activity

The activity of α-amylase was analyzed as described by Black et al. (1996). After incubation of intact caryopses for 24, 26 or 28 h or embryoless caryopses, 25 in five replicates, for 28 h in darkness at 20 °C in the presence of distilled water or SW (1:1000 v/v), the caryopses were ground using a pre-chilled mortar and pestle in ice-cold extraction buffer (fresh weight: extraction buffer, 1:10, w/v). All the extraction steps were performed at 4 °C. The extraction buffer contained 20 mM Tris–maleate, pH 6.2, with 1.0 mM CaCl2. Barley malt α-amylase was used for constructing the calibration curve. Results were expressed as U mg−1 protein. One unit (U) was equivalent to the amount of enzyme liberating 1 mg of maltose from starch at 37 °C and pH 6.2.

For the analysis of α-amylase isoenzymes activity, total proteins (50 μg) extracted from untreated and treated caryopses, were separated on 7% native-PAGE gel containing 0.3% (w/v) starch in the Laemmli (1970) buffer system without sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). The gels were incubated overnight at 35 °C in 50 mM sodium acetate (pH 5.6) containing 1 M CaCl2. α-Amylase isoenzymes activity was examined by staining the gel with I2/KI solution.

β-Amylase (EC 3.2.1.2) activity

β-Amylase activity was measured according to Bernfeld (1955). Caryopses, 25 in five replicates, incubated in the presence of distilled water or SW (1:000 v/v) for 24, 26 or 28 h in darkness at 20 °C were homogenized in 1.0 ml of ice-cold 16 mM sodium acetate buffer, pH 4.8 (fresh weight: extraction buffer, 1:40, w/v). All the extraction steps were performed at 4 °C. The results were expressed as U mg−1 protein. One unit (U) is defined as the amount of enzyme liberating 1 mg of maltose from starch in 5 min at 37 °C and pH 4.8.

Determination of starch content

Total starch content in intact or embryoless caryopses, 25 in five replicates, incubated in the presence of distilled water or SW (1:000 v/v) for 28 h in darkness at 20 °C was estimated using the Total Starch Assay Kit (Megazyme International Ireland Ltd.) according to manufacturer’s protocol.

Protein assay

The protein content in the enzymatic extracts was assayed as described by Bradford (1976), using bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard.

Determination of nuclear DNA and β-tubulin contents

The nuclear DNA contents in radicle with coleorhiza (RC) were determined using flow cytometry. For cell cycle activity determination, caryopses, 25 in 5 replicates, were incubated at 20 °C for 0, 24, 26 and 28 h in the dark in distilled water or SW (1:1000 v/v). Twenty-five RCs were isolated from the imbibed caryopses and, using a razor blade, were chopped and placed in 2 ml of a nucleus isolation buffer (45 mM MgCl2, 30 mM sodium citrate, 20 mM MOPS, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 2 µg/mL DAPI) (Galbraith et al. 1983) for 2 min, following which they were incubated for 10 min at 25 °C. Subsequently, the suspension was passed through a 20-µm nylon mesh. The DAPI-stained nuclei were analyzed using a Partec PAII flow cytometer (Partec). The populations of 2C and 4C nuclei were measured on 10,000 nuclei.

The extraction and detection of β-tubulin by Western blotting was conducted following de Castro et al. (1995). Proteins were extracted from radicles with coleorhiza cell tips (50) isolated from caryopses after imbibition for various periods of time in distilled water or SW (1:1000 v/v) for 24, 26 or 28 h in darkness at 20 °C. Samples containing 50 µg of protein were separated on 15% SDS-PAGE gel following Laemmli (1970). Pure bovine brain tubulin (Cytoskeleton, Inc.) was loaded as a control in amounts of 10 and 30 ng (molecular mass ~50 kDa). After electrophoresis, the gels were electroblotted onto PVDF membranes (Millipore). The blotting membranes were probed with the mouse monoclonal anti-β-tubulin antibody (clone KMX-1) (Millipore). The data were expressed as immunoblot band visualization and densitometry analysis of immunoblot β-tubulin (ng). Band intensities were determined using the Fiji ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

The mean ± standard deviation (SD) values of three or five replicates are shown. The means were also analyzed for significance using one-way or two-way analysis of variance, ANOVA (Statistica for Windows v. 10.0, Stat-Soft Inc., Tulsa, OK, USA). Duncan’s multiple range test was used to test for significance of differences (P ≤ 0.05) for germination percentage and biochemical assay results for A. fatua caryopses.

Results

Effects of SW on the uptake of water and germination of caryopses

Uptake of water by dormant caryopses kept in water or exposed to SW was increasing for 12 h of incubation (Fig. 1). This period is regarded as the first phase of imbibition. At the second phase, which started after 12 h, the water content was observed to increase somewhat in the caryopses both kept in water and exposed to SW. Beginning from hour 20, the percentage of ruptures increased with incubation time in SW-treated caryopses. As of hour 28, SW resulted in increased protrusion of coleorhiza through the covers. After the subsequent 2 h, the beginning of the third phase was marked by the appearance of caryopses with coleorhiza ruptured by the radicle. During this phase, the water uptake was observed to increase, which was associated with a progressively growing protrusion rate of coleorhiza and radicles; after 48 h, about 80 and 40% caryopses were with coleorhiza and radicle, respectively. The third phase was observed only in the treated caryopses. After 48 h, the untreated caryopses somewhat increased their water uptake; as little as 10 and 5% of the caryopses featured coat break-down and coleorhiza protrusion, respectively. Extended incubation increased the proportion of untreated caryopses with protruding radicle only up to about 20%. After 96 h of incubation in SW, almost all the caryopses showed radicles protruding through the coleorhiza. Such caryopses were regarded as germinated.

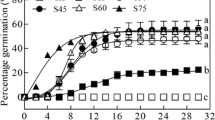

Effects of SW on germination of florets and caryopses at different temperatures

Freshly harvested florets were dormant and did not germinate in the dark at temperatures from 5 to 35 °C (Fig. 2a). SW at dilution of 1:10,000 (v/v) did not affect germination at any of the temperatures tested. SW at dilutions of 1:1000, 1:500 or 1:100 (v/v) markedly stimulated germination and 53–67% of florets were germinated at 10 and 15 °C after 5 days (Fig. 2a). At 20 °C, SW was most effective at dilutions of 1:500 and 1:100 (v/v); 50 and 57% of florets, respectively, being germinated. The SW-induced germination extent at 25 °C varied between 20 and 33%. SW applied at all the dilutions did not affect germination at temperatures above 25 °C. Not only the percentage of germinated florets, but also Timson’s index, a measure of germination rate, was affected by the SW treatment. Florets treated with 1:500 and 1:100 (v/v) SW germinated faster at 10–20 °C, compared to florets imbibed in the presence of 1:1000 (v/v) SW (Fig. 2b).

Effects of SW on the germination (a, c) and Timson’s index (%) (b, d) in A. fatua florets (a, b) or caryopses (c, d) after 5 days of incubation at different temperatures. Vertical bars indicate ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with the Duncan’s post hoc test on arcsine (×/10)-transformed data was used to determine the significance of differences. Mean values with different letters (a–j) are significantly different (P < 0.05)

Untreated caryopses did not germinate at the lowest temperature, 5 °C, but at 10 and 15 °C, about 55% of the seeds germinated (Fig. 2c). However, at 20 °C, only ca. 20% of caryopses germinated, no germination being observed at a temperature higher than 20 °C. At the highest dilution (1:10,000), SW increased germination percentage at 5, 20 and 25 °C only slightly; however, dilutions of 1:1000, 1:500 or 1:100 (v/v) induced almost complete caryopsis germination at 15 and 20 °C. The germination extent due to the presence of SW at 25 °C ranged between 63 and 72%. At 30 °C, only SW at dilutions of 1:500 and 1:100 (v/v) induced germination which amounted to 24%. SW also increased Timson’s index. Caryopses treated with SW at dilutions of 1:1000, 1:500 and 1:100 (v/v) germinated faster at 15–25 °C, compared to caryopses imbibed in presence of water and 1:10,000 (v/v) SW (Fig. 2d).

Effects of SW on germination of florets and caryopses following floret dry storage

Dormant A. fatua florets are not able to germinate at 20 °C (Fig. 3a). Dry storage of florets at 25 °C for 2 weeks resulted in germination of 10% of florets. However, extension of the dry storage period progressively increased the germination, with 67% of the florets germinating after 12 weeks of storage. SW at the highest dilution did not affect germination of florets stored for up to 12 weeks. SW, only at its lowest dilution of 1:1000 (v/v), induced germination in only 26% of the completely dormant florets (Fig. 3a). After 2 weeks of storage, germination increased up to 23, 36 and 76% in the presence of SW at dilutions of 1:30,000, 1:10,000 and 1:1000 (v/v), respectively, compared to 10% in the control. All the florets, stored for 12 weeks, germinated in the presence of SW at the above dilutions, while about 70% of florets germinated in water. Likewise, the rate of caryopsis germination was observed to increase with the time of dry storage (Fig. 3b). The highest effect of SW on the germination rate, regardless of storage time, was found at the lowest dilution. SW at all dilutions increased Timson’s index of florets stored for 8 or 12 weeks.

Effects of SW on the germination (a, c) and Timson’s index (%) (b, d) after 5 days of incubation of A. fatua florets (a, b) or caryopses (c, d) at 20 °C after previous dry storage of florets at 25 °C for various times. Vertical bars indicate ± SD. Two-way ANOVA with the Duncan’s post hoc test on arcsine (×/10)-transformed data was used to determine the significance of differences. Mean values with different letters (a–k) are significantly different (P < 0.05)

Dormant A. fatua seeds germinated poorly at 20 °C (Fig. 3c), as only ca. 20% of caryopses germinated after 5 days. Seed germination was not changed after the florets were stored dry at 25 °C for 2 weeks. However, extension of dry storage time tended to increase the germination success. After 12 weeks of storage, all the seeds could germinate. SW used at dilutions of 1:10,000 and 1:1000 (v/v) increased the germination of dormant caryopses from non-stored florets to 35 and 88%, respectively, compared to ca. 20% in the control. SW dilutions of 1:30,000 and 1:10,000 (v/v) increased the germination success after various dry storage times. After 4 and 8 weeks, all the dry-stored caryopses germinated completely in the presence of SW at dilutions of 1:30,000 and 1:10,000 (v/v), respectively. All the caryopses from florets stored for 12 weeks germinated in the presence of SW, regardless of the dilution. Like the caryopsis germination success, Timson’s index was dependent on SW dilution (Fig. 3d). The highest effect of SW occurred with the lowest dilution. SW at 1::10 000 slightly enhanced the germination rate of seeds from florets kept dry for 12 weeks.

Effects of SW and gibberellin biosynthesis inhibitor on germination of caryopses

To find out if SW stimulated caryopsis germination because of the associated synthesis of endogenous gibberellins, PAC, an inhibitor of gibberellin biosynthesis was used alone and in combination with SW. As reported in the previous experiment, dormant seeds germinated poorly at 20 °C (ca. 15%), and the treatment involving 1:1000 (v/v) SW led, after 5 days, to a germination of 97% (Table 1). PAC administered at the concentration of 10−4 M hampered the germination of dormant seeds. In the presence of SW, PAC distinctly interfered with the enhancing effect of SW, resulting in germination of as few as 20% of caryopses. After 5 days of preincubation in water, caryopses showed a strong response to GA3 applied at 10−5 M; 5 days after the transfer from water to GA3, the germination success was 95%. PAC-induced inhibition of the stimulatory effect of SW was completely reversed after an additional 5-day incubation in the presence of GA3.

Effects of SW on α- and β-amylase activities in caryopses

After 24-h imbibition of caryopses in water, the α-amylase activity was similar to that in dry caryopses (Table 2). The α-amylase activity was not changed when dormant seeds were kept in water for as long as 28 h. SW increased the α-amylase activity from 24 to 28 h of imbibition. The highest activity of the enzyme was observed after 28 h, 2 h before the start of radicle protrusion through the coleorhiza; the activity was about 2.4 times higher than that recorded in caryopses kept in water for the same period. The beta-amylase activity was similar throughout the time the seeds were kept in water. SW enhanced the activity to a similar level after 26 and 28 h of imbibition. After 28-h incubation in SW, the enzyme’s activity was almost 1.4 times higher than that in caryopses incubated in water.

Gel staining after separation of proteins from the caryopses revealed the presence of two α-amylase isoforms, AMY-1 and AMY-2 (Table 3). The isoforms were detected in dry seeds and in the seeds kept in water or SW for 24, 26 and 28 h. AMY-1 representing dry seeds and those kept in water for 24, 26 and 28 h remained slightly active; more intense bands were related to AMY-2. Intensity of bands was independent of the incubation time in water. SW increased the intensity of the bands representing AMY-1 and AMY-2, compared to the control (Table 3). Intensity of these bands was the highest after 28h incubation.

Effects of SW on the α-amylase activity and starch content in intact caryopses and embryoless ones incubated for 28 h were also determined (Table 4). Incubation of intact caryopses in water increased the α-amylase activity and decreased the starch content. The α-amylase activity in intact caryopses treated with SW was 3.3 times higher than that in the untreated intact caryopses. SW, too, decreased the starch content after 28 h by a factor of 2.9. Imbibition of embryoless caryopses in water tended to increase the α-amylase activity and reduced the starch content. In embryoless caryopses, SW increased the α-amylase activity and reduced the starch content by factors of 1.6 and 1.3, respectively.

Effects of SW on nuclear DNA and β-tubulin contents in radicle tip with coleorhiza

In dry dormant caryopses, 93% of cells in the radicle with coleorhiza (RC) contained 2C DNA (Table 5). Imbibition of dormant caryopses in water for 24–28 h did not affect the distribution of nuclei with different DNA contents. SW, applied for 24 or 28 h, decreased the percentage of nuclei with 2C, but increased in phase S, and 4C DNA.

SW treatment for 28 h resulted in about 1.6-fold decrease in the percentage of nuclei with 2C DNA in RC of the caryopses, compared to RC from untreated caryopses, with the percentage of nuclei in phase S increasing by about 3.5 times (Fig. 4). The percentage of nuclei with 4C DNA in RC from SW-treated caryopses increased by a factor of 5.

Beta-tubulin, which is contained in the microtubular cytoskeleton, was not detectable in RC from dry seeds and those kept in water for 24 h (Table 6). Accumulation of β-tubulin was detected only just 28 h after imbibition in water. Beta-tubulin was detected in RC just after 24 h as a result of the exposure to SW. The signal was intensified when incubation in the presence of SW was extended to up to 28 h. The signal intensity was 7.5 times higher than that for RC of untreated caryopses.

Discussion

Most annual weed species in agricultural systems in temperate climate are dormant when dispersed in late spring and early summer. Dormancy can be defined simply as a seed trait that blocks the germination of viable seeds under favorable conditions (Bewley 1997). Dormancy in freshly harvested cereal grain is seldom absolute at all under any environmental condition (Rodríguez et al. 2015). In temperate cereals, dormancy is expressed strongly at relatively high temperatures, usually above 15–20 °C. Florets (caryopses covered with the lemma and palea) of Avena fatua after harvest did not germinate at temperatures from 5 up to 35 °C (Fig. 2a; Kępczyński et al. 2013). Like in earlier experiments (Kępczyński et al. 2013), the removal of the hulls from A. fatua florets resulted in germination at 10 and 15 °C (up to ca. 60%) (Fig. 2c). The results presented indicate that florets were totally dormant at all the temperatures tested, but seeds were partly dormant at 10 and 15 °C and fully dormant above 15 °C. Thus, dormancy expression in A. fatua caryopses, like in cereal grains (Rodríguez et al. 2015), depends on the incubation temperature. Difference in germination between florets and caryopses at 10 and 15 °C indicates difference in the depth of dormancy as well as various mechanisms of dormancy associated with the presence or absence of the hulls. The inhibitory effect of the lemma and palea on germination of A. fatua florets could be related to the presence of phenolic compounds which restrict the access of oxygen to the embryo. Limitation of oxygen supply to the embryo by oxygen fixation as a result of polyphenol oxidase-mediated oxidation of phenolic compounds in the lemma and palea has been suggested to be responsible for the dormancy of Hordeum vulgare (Lenoir et al. 1986).

SW produced from burnt dry grass leaves proved to be an effective germination stimulant in dormant florets and caryopses at temperatures from 10 to 25 °C, respectively (Fig. 2a, c). This finding is in agreement with results of Adkins and Peters (2001) who demonstrated that a commercially available SW solution (Seed Starter®) stimulated germination of both dormant florets and caryopses of A. fatua. Moreover, not only did SW enhance the final germination success, but it also accelerated germination of both A. fatua florets and caryopses (Fig. 2b, d). The data presented are also in agreement with earlier results showing that aqueous smoke extract produced from burnt Themeda triandra leaves also removes dormancy in A. fatua florets and caryopses (Kępczyński et al. 2006). The reaction of A. fatua florets or seeds to SW, like in the case of T. triandra seeds (Baxter et al. 1995), was independent of plant material used for smoke production. Seed dormancy of several monocot plant species such as Bromus tectorum (Allen et al. 1995), Oryza sativa (Doherty and Cohn 2000) and Hordeum vulgare (Barrero et al. 2009) can be released after dry storage. Likewise, dormancy of A. fatua caryopses and florets was released as a result of floret dry storage (Fig. 3). Dormancy release in A. fatua caryopses, as a result of dry storage of florets, has already been reported (Foley 1994). The release of dormancy in A. fatua caryopses due to dry storage could be associated with changes in the ABA level; the release of dormancy in H. vulgare caryopses by dry storage was related to a decrease of the ABA content in embryo during imbibition (Jacobsen et al. 2002). Earlier studies found dormancy breaking factors such as KAR1 or GA3 to reduce the ABA content in A. fatua embryos (Cembrowska-Lech et al. 2015). At suboptimal dilutions higher than 1:1000 v/v, responses to SW in florets (Fig. 3a) or caryopses (Fig. 3c), stored dry for different periods of time, indicated that the demand for this compound dwindled as the dry storage proceeded. Partly dormant seeds were more responsive to both SW (Fig. 3c) and KAR1 (Kępczyński et al. 2013) than the completely dormant caryopses. Both florets (Fig. 3b), and the seeds from the florets (Fig. 3d), kept dry for different times, germinated in the presence of SW faster than in water. A similar response was observed when caryopses from stored florets were incubated in the presence of KAR1 (Kępczyński et al. 2013).

To find out whether the SW mode of action might be associated with endogenous gibberellin, dormant A. fatua seeds were imbibed in the presence of PAC, a gibberellin biosynthesis inhibitor (Table 1). The enhancing effect of SW was not visible with PAC, suggesting the gibberellin biosynthesis involvement in the response to SW. Reversal of the inhibitory effect of PAC on caryopsis germination in the presence of SW was possible by exogenous GA3. Thus, it confirms the involvement of gibberellin biosynthesis in caryopsis response to SW, which was the case with KAR1 (Kępczyński et al. 2013). Earlier experiments performed on Lactuca sativa (Van Staden et al. 1995) and Nicotiana attenuata (Schwachtje and Baldwin 2004) seeds showed, too, that gibberellin synthesis could be considered as a possible component of the mechanism involved in smoke-stimulated germination.

Uptake of water is essential for germination. Like in the case of non-dormant seeds (Bewley et al. 2013), uptake of water by A. fatua caryopses in the presence of SW was triphasic (Fig. 1). Both non-treated and SW-treated dormant caryopses can take up water during two phases. Phase II (germination sensu stricto) has usually been considered as the most important stage because all of the germination-required metabolic reactions are reactivated during this period (He and Yang 2013). Caryopses incubated in the presence of SW, in contrast to those incubated in water, were able to complete germination (radicles protruded through the coleorhiza; the end of germination sensu stricto). Thus, only these caryopses could enter phase III (post-germination).

At the late stage of phase II of water uptake, SW enhanced the activity of α-amylase, two isoforms, and β-amylase (Tables 2, 3), i.e., before the radicle protrusion and even before the coleorhiza protrusion, like in the case of KAR1 or GA3 application (Kępczyński et al. 2013). Thus, before dormant seeds are prepared for germination through SW treatment, their metabolic activity is enhanced by stimulation of starch-breaking amylases. Similarly, a large increase in the α-amylase activity was found at phase II of rice seed germination (He and Yang 2013). Earlier publications proposed that GA3 -induced hydrolysis of starch reserves is a post-germinative event not associated with GA3 -induced breaking of dormancy (Simpson and Naylor 1962; Foley et al. 1993). According to the present views, starch is a major carbon source for generating the energy required for seed germination and early seedling growth (Hong et al. 2012; Yan et al. 2014; Shaik et al. 2014). Moreover, α-amylase was considered as a candidate biomarker for rice seed germination (He and Yang 2013). The aleurone layer of caryopsis is a secretory tissue surrounding the starchy endosperm wherein the synthesis and secretion of hydrolytic enzymes, including amylases, respond to the release of gibberellins from the embryo (Lovegrove and Hooley 2000; Kaneko et al. 2002). To clarify the influence of SW on the α-amylase activity, assays to determine the enzyme’s activity in intact and embryoless caryopses were conducted. The embryoless caryopsis responded to SW by increasing α-amylase activity. However, the α-amylase activity and starch degradation in embryoless caryopses were lower than in the intact caryopses (Table 4). These results may indicate that SW can only partially replace the influence of endogenous gibberellins from embryo on the aleurone layer. On the other hand, it cannot be ruled out that the effect observed can be due to the cooperation between SW and endogenous gibberellins which could accumulate at some amount during caryopsis maturation.

The role of cell cycle in the germination of non-dormant and dormant seeds is still not completely clear. There are data showing that radicle protrusion does not require the cell cycle activation (Baíza et al. 1989; Jing et al. 1999), whereas others indicate that activation of the cell cycle takes place prior to radicle protrusion (de Castro et al. 2000; Barrôco et al. 2005; Masubelele et al. 2005; Gendreau et al. 2008). In dry and dormant A. fatua caryopses imbibed in water at 20 °C, 93% of cells in the radicle with coleorhiza (RC) were arrested at the G1 phase (Table 5; Cembrowska-Lech and Kępczyński 2016). Cells arrested at G1 were also observed in dry dormant Lycopersicon esculentum seeds (de Castro et al. 2001) and in H. vulgare caryopses (Gendreau et al. 2012). Analysis of nuclear DNA content during imbibition of dormant caryopses in water may suggest that the dormancy in A. fatua caryopses is associated with inhibition of the cell cycle. SW decreased the percentage of nuclei at the G1 cell cycle phase and increased the percentage at S and G2, after 24 and 28 h of imbibition. SW-induced germination of dormant caryopses, like in the case of KAR1 application (Cembrowska-Lech and Kępczyński 2016), was associated with cell cycle activation found 4 h before the coleorhiza protrusion and 6 h prior to protrusion of radicles (Table 5). Thus, it can be concluded that induction of germination of dormant seeds by both SW and KAR1 involves onset of the cell cycle at phase II, prior to the radicle protrusion. Likewise, dormancy release in seeds of L. esculentum (de Castro et al. 2001) was associated with induction of DNA replication before the radicles started protruding through the covering structures. An experiment involving the detection and densitometry analysis indicates that β-tubulin, necessary in the cell cycle, appeared due to SW treatment after 24 h, i.e. when the cell cycle was initiated. Earlier studies showed that releasing dormancy in L. esculentum seeds was associated with accumulation of β-tubulin (de Castro et al. 2001).

To summarize, plant-derived smoke is an effective stimulant of germination not only in A. fatua caryopses, but also in florets. Florets were completely dormant at all the incubation temperatures, the dormancy expression of caryopses being dependent on the incubation temperature. Florets were less sensitive to SW at temperatures above 20 °C than caryopses. A progressive release of dormancy by dry storage increased the smoke sensitivity in both florets and caryopses. SW-induced germination in dormant caryopses involves the initiation of stored starch mobilization and the cell cycle activation at the late stage of phase II germination sensu stricto. The release of dormancy by SW requires gibberellin biosynthesis.

Author contribution statement

JK initiated and designed the research, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. DC-L conducted the experiments and statistical analyses, interpreted the results and wrote the manuscript. All authors read, reviewed and approved the manuscript.

References

Adkins SW, Peters NCB (2001) Smoke derived from burnt vegetation stimulates germination of arable weeds. Seed Sci Res 11:213–222

Adkins SW, Loewen M, Symons SJ (1986) Variation within pure lines of wild oats (Avena fatua L.) in relation to degree of primary dormancy. Weed Sci 34:859–864

Allen PS, Meyer SE, Beckstead J (1995) Patterns of seed after-ripening in Bromus tectorum L. J Exp Bot 46:1737–1744

Baíza AM, Vázquez-Ramos J, Sánchez de Jiménez E (1989) DNA synthesis and cell division in embryonic maize tissues during germination. J Plant Physiol 135:416–421

Barrero JM, Talbot MJ, White RG, Jacobsen JV, Gubler F (2009) Anatomical and transcriptomic studies of the coleorhiza reveal the importance of this tissue in regulating dormancy in barley. Plant Physiol 150:1006–1021

Barrôco RM, Van Poucke K, Bergervoet JHW, De Veylder L, Groot SPC, Inzé D, Engler G (2005) The Role of the cell cycle machinery in resumption of postembryonic development. Plant Physiol 137:127–140

Baxter BJM, Van Staden J, Granger JE, Brown NAC (1994) Plant-derived smoke and smoke extracts stimulate seed germination of the fire-climax grass Themeda triandra Forssk. Environ Exper Bot 34:217–223

Baxter BJM, Granger JE, Van Staden J (1995) Plant-derived smoke and seed germination: is all smoke good smoke? That is the burning question. S Afr J Bot 61:275–277

Bernfeld P (1955) Amylases, α and β. Methods Enzymol 1:149–158

Bewley JD (1997) Seed germination and dormancy. Plant Cell 9:1055–1066

Bewley JD, Bradford KJ, Hilhorst HWM, Nonogaki H (2013) Seeds: physiology of development, germination and dormancy, 3rd edn. Springer, New York

Black M, Corbineau F, Grzesik M, Guy P, Côme D (1996) Carbohydrate metabolism in the developing and maturing wheat embryo in relation to its desiccation tolerance. J Exp Bot 295:161–169

Bradford MM (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein dye binding. Anal Biochem 72:248–254

Cembrowska-Lech D, Kępczyński J (2016) Gibberellin-like effects of KAR1 on dormancy release of Avena fatua caryopses include participation of non-enzymatic antioxidants and cell cycle activation in embryos. Planta 243:531–548

Cembrowska-Lech D, Koprowski M, Kępczyński J (2015) Germination induction of dormant Avena fatua caryopses by KAR1 and GA3 involving the control of reactive oxygen species (H2O2 and O •−2 ) and enzymatic antioxidants (superoxide dismutase and catalase) both in the embryo and the aleurone layers. J Plant Physiol 176:169–179

Daws MI, Davies J, Pritchard HW, Brown NAC, Van Staden J (2007) Butenolide from plant-derived smoke enhances germination and seedling growth of arable weed species. Plant Growth Regul 51:73–82

de Castro RD, Zheng X, Bergervoet JHW, De Vos RCH, Bino RJ (1995) β-tubulin accumulation and DNA replication in imbibing tomato seeds. Plant Physiol 109:499–504

de Castro RD, van Lammeren AAM, Groot SPC, Bino RJ, Hilhorst HWM (2000) Cell division and subsequent radicle protrusion in tomato seeds are inhibited by osmotic stress but DNA synthesis and formation of microtubular cytoskeleton are not. Plant Physiol 122:327–335

de Castro RD, Bino RJ, Jing H-C, Kieft H, Hilhorst HWM (2001) Depth of dormancy in tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) seeds is related to the progression of the cell cycle prior to the induction of dormancy. Seed Sci Res 11:45–54

De Lange JH, Boucher C (1990) Autecological studies on Audouinia capitata (Bruniaceae). I. Plant-derived smoke as a seed germination cue. S Afr J Bot 56:700–703

Doherty LC, Cohn MA (2000) Seed dormancy in red rice (Oryza sativa). XI. Commercial liquid smoke elicits germination. Seed Sci Res 10:415–421

Downes KS, Lamont BB, Light ME, Van Staden J (2010) The fire ephemeral Tersonia cyathiflora (Gyrostemonaceae) germinates in response to smoke but not the butenolide 3-methyl-2H-furo[2,3-c]pyran-2-one. Ann Bot 106:381–384

Flematti GR, Ghisalberti EL, Dixon KW, Trengove RD (2004) A compound from smoke that promotes seed germination. Science 305:977

Flematti GR, Ghisalberti EL, Dixon KW, Trengove RD (2009) Identification of alkyl substituted 2H-furo[2,3-c]pyran-2-ones as germination stimulants present in smoke. J Agric Food Chem 57:9475–9480

Flematti GR, Merritt DJ, Piggott MJ, Trengove RD, Smith SM, Dixon KW, Ghisalberti EL (2011) Burning vegetation produces cyanohydrins that liberate cyanide and stimulate seed germination. Nat Commun 2:360

Foley ME (1994) Temperature and water status of seed affect after-ripening in wild oat (Avena fatua). Weed Sci 42:200–204

Foley ME, Nichols MB, Myers SP (1993) Carbohydrate concentrations and interactions in afterripening-responsive dormant Avena fatua caryopses induced to germinate by gibberellic acid. Seed Sci Res 3:271–278

Galbraith DW, Harkins KR, Maddox JM, Ayres NM, Sharma DP, Firoozabady E (1983) Rapid flow cytometric analysis of cell cycle in intact plant tissues. Science 220:1049–1051

Gendreau E, Romaniello S, Barad S, Leymarie J, Benech-Arnold R, Corbineau F (2008) Regulation of cell cycle activity in the embryo of barley seeds during germination as related to grain hydration. J Exp Bot 59:203–212

Gendreau E, Cayla T, Corbineau F (2012) S phase of the cell cycle: a key phase for the regulation of thermodormancy in barley grain. J Exp Bot 63:5535–5543

He D, Yang P (2013) Proteomics of rice seed germination. Front Plant Sci 4:1–9

Hong YF, Ho THD, Wu CF, Ho SL, Yeh RH, Lu CA, Chen PW, Yu LC, Chao A, Yu SM (2012) Convergent starvation signals and hormone crosstalk in regulating nutrient mobilization upon germination in cereals. Plant Cell 24:2857–2873

Jacobsen JV, Pearce DW, Poole AT, Pharis RP, Mander LN (2002) Abscisic acid, acid and gibberellin contents associated with dormancy and germination in barley. Physiol Plant 115:428–441

Jefferson LV, Pennacchio M, Havens-Young K (2014) Ecology of plant-derived smoke: its use in seed germination. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Jing HC, van Lammeren AAM, de Castro RD, Bino RJ, Hilhorst HWM, Groot SPC (1999) β-Tubulin accumulation and DNA synthesis are sequentially resumed in embryo organs of cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) seeds during germination. Protoplasma 208:230–239

Kaneko M, Itoh H, Ueguchi-Tanaka M, Ashikari M, Matsuoka M (2002) The α-amylase induction in endosperm during rice seed germination is caused by gibberellin synthesized in epithelium. Plant Physiol 128:1264–1270

Kępczyński J, Van Staden J (2012) Interaction of karrikinolide and ethylene in controlling germination of dormant Avena fatua L. caryopses. Plant Growth Regul 67:185–190

Kępczyński J, Białecka B, Light ME, Van Staden J (2006) Regulation of Avena fatua seed germination by smoke solution, gibberellin A3 and ethylene. Plant Growth Regul 49:9–16

Kępczyński J, Cembrowska D, Van Staden J (2010) Releasing primary dormancy in Avena fatua L. caryopses by smoke-derived butenolide. Plant Growth Regul 62:85–91

Kępczyński J, Cembrowska-Lech D, Van Staden J (2013) Necessity of gibberellin for stimulatory effect of KAR1 on germination of dormant Avena fatua L. caryopses. Acta Physiol Plant 35:379–387

Laemmli UK (1970) Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 227:680–685

Lenoir C, Corbineau F, Côme D (1986) Barley (Hordeum vulgare) seed dormancy as related to glumella characteristics. Physiol Plant 68:301–307

Lovegrove A, Hooley R (2000) Gibberellin and abscisic acid signaling in aleurone. Trends Plant Sci 5:102–110

Masubelele NH, Dewitte W, Menges M, Maughan S, Collins C, Huntley R, Nieuwland J, Scofield S, Murray JAH (2005) D-type cyclins activate division in the root apex to promote seed germination in Arabidopsis. PNAS 102:15694–15699

Pošta M, Light ME, Papenfus HB, Van Staden J, Kohout L (2013) Structure–activity relationships of analogs of 3,4,5-trimethylfuran-2(5H)-one with germination inhibitory activities. J Plant Physiol 170:1235–1242

Rodríguez MV, Barrero JM, Corbineau F, Gubler F, Benech-Arnold RL (2015) Dormancy in cereals (not too much, not so little): about the mechanisms behind this trait. Seed Sci Res 25:99–119

Schwachtje J, Baldwin IT (2004) Smoke exposure alters endogenous gibberellin and abscisic acid pools and gibberellin sensitivity while eliciting germination in the post-fire annual, Nicotiana attenuata. Seed Sci Res 14:51–60

Shaik SS, Carciofi M, Martens HJ, Hebelstrup KH, Blennow A (2014) Starch bioengineering affects cereal grain germination and seedling establishment. J Exp Bot 65:2257–2270

Simpson GM (2007) Seed dormancy in grasses. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Simpson GM, Naylor JM (1962) Dormancy studies in seed of Avena fatua. A relationship between maltase, amylases, and gibberellin. Can J Bot 40:1659–1673

Stevens JC, Merritt DJ, Flematti GR, Ghisalberti EL, Dixon KW (2007) Seed germination of agricultural weeds is promoted by the butenolide 3-methyl-2H-furo[2,3-c]pyran-2-one under laboratory and field conditions. Plant Soil 298:113–124

Timson J (1965) New method of recording germination data. Nature 207:216–217

Van Staden J, Jäger AK, Strydom A (1995) Interaction between a plant-derived smoke extract, light and phytohormones on the germination of light-sensitive lettuce seeds. Plant Growth Regul 17:213–218

Van Staden J, Jäger AK, Light ME, Burger BV (2004) Isolation of the major germination cue from plant-derived smoke. S Afr J Bot 70:654–659

Yan D, Duermeyer L, Leoveanu C, Nambara E (2014) The functions of the endosperm during seed germination. Plant Cell Physiol 55:1521–1533

Acknowledgements

The study was partially supported by the National Science Centre (Poland) Grant No. NN310 726340. We are indebted to Dr Teresa Radziejewska for linguistic assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Communicated by A Gniazdowska-Piekarska.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Cembrowska-Lech, D., Kępczyński, J. Plant-derived smoke induced activity of amylases, DNA replication and β-tubulin accumulation before radicle protrusion of dormant Avena fatua L. caryopses. Acta Physiol Plant 39, 39 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-016-2329-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11738-016-2329-x