Abstract

The neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) plays a critical role in brain circuits mediating motor control, attention, learning and memory. Cholinergic dysfunction is associated with multiple brain disorders including Alzheimer’s Disease, addiction, schizophrenia and Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The presynaptic choline transporter (CHT, SLC5A7) is the major, rate-limiting determinant of ACh production in the brain and periphery and is consequently upregulated during tasks that require sustained attention. Given the contribution of central cholinergic circuits to the control of movement and attention, we hypothesized that functional CHT gene variants might impact risk for ADHD. We performed a case-control study, followed by family-based association tests on a separate cohort, of two purportedly functional CHT polymorphisms (coding variant Ile89Val (rs1013940) and a genomic SNP 3’ of the CHT gene (rs333229), affording both a replication sample and opportunities to reduce potential population stratification biases. Initial genotyping of pediatric ADHD subjects for two purportedly functional CHT alleles revealed a 2–3 fold elevation of the Val89 allele (n = 100; P = 0.02) relative to healthy controls, as well as a significant decrease of the 3’SNP minor allele in Caucasian male subjects (n = 60; P = 0.004). In family based association tests, we found significant overtransmission of the Val89 variant to children with a Combined subtype diagnosis (OR = 3.16; P = 0.01), with an increased Odds Ratio for a haplotype comprising both minor alleles. These studies show evidence of cholinergic deficits in ADHD, particularly for subjects with the Combined subtype, and, if replicated, may encourage further consideration of cholinergic agonist therapy in the disorder.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention deficit/hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), as described by the DSM-IV-TR (Diagnostic Statistical Manual, 4th edition, text revised, [1], is a psychiatric disorder characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity. ADHD is the most common psychiatric disorder among children, with an estimated prevalence of 3–10% and a 3–4 fold increased prevalence in males. Although formally diagnosed in childhood, 60% of these cases have been suggested to persist into adulthood [2, 3]. ADHD subjects can exhibit predominantly inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms, but also may display a combined subtype, exhibiting elevations on both symptom dimensions. Multiple studies have examined the contributions of genetic factors to the development of ADHD [4–6] with current models most consistent with a complex polygenic disorder and a heritability estimated at ~80%.

Molecular genetic studies in patients with ADHD have identified candidate genes that may contribute to the pathophysiology of ADHD [6, 7]. Prominent focus has centered on genes impacting dopamine and norepinephrine functioning [8–11] due to their roles in governing signaling in cognitive and motor circuits, as well as being targeted by current pharmacotherapies [12, 13]. Less attention has been given to genes impacting acetylcholine (ACh) signaling as determinants of ADHD risk [14, 15], despite the major role played by basal ganglia cholinergic interneurons in movement control [16, 17] and the activity of thalamic and cortical cholinergic pathways that regulate sensory gating and attention [18, 19]. Thus, tasks requiring sustained attention activate cortical cholinergic neurotransmission, whereas muscarinic ACh receptor (mAChR) antagonists (e.g. scopolamine) produce cognitive and motor impairments in both animals and humans [20, 21]. Notably, two cholinergic genes (CHRNA4 and CHNRA7) that encode α4 and α7 subunits of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, respectively, have been associated with ADHD [22, 23].

A major determinant of cholinergic signaling capacity is the presynaptic choline transporter (CHT) which transports choline into cholinergic terminals to sustain ACh synthesis [24, 25]. Genetic deletion of the mouse CHT gene results in paralysis and early postnatal lethality, most likely arising from an inability to sustain cholinergic signaling at the neuromuscular junction. Depolarization of cholinergic neurons in vitro elevates choline uptake (increase in Vmax) that is supported by a translocation of CHT protein to the plasma membrane [25–27]. Ex vivo measurements of CHT trafficking in rat cortex following exposure to attention demanding tasks also reveal elevated CHT surface expression [28].

The human high-affinity choline transporter gene (hCHT, SLC5A7) is located on chromosome 2q12 and has been demonstrated to be a source of genetic variation for cholinergic traits [29, 30]. Okuda and colleagues reported the identification of a common, nonsynonymous SNP (+265 A/G; rs1013940) that encodes a substitution of isoleucine for valine in position 89 (Ile89Val) of hCHT transmembrane domain 3 [29]. In transfected cells, Val89-containing CHT protein exhibits an ~50–60% maximal rate of choline uptake as compared to Ile89 CHT despite normal surface expression [29]. CHT heterozygous mice display significant reductions in CNS ACh levels and muscarinic receptors, as well as fatigue in sustained motor tasks [31]. The expression of a CHT hypomorph in a significant fraction of humans (6% reported minor allele frequency) makes the Val89 variant an exceedingly interesting candidate in imposing risk for disorders associated with cholinergic deficits. Indeed, we recently described a significant association of the Val89 variant with major depression [32]. Another polymorphism, originally designated as a component of the CHT 3’UTR (+4067 G/T; rs333229), here designated the 3’SNP (see Methods) has been associated with altered cholinergic tone, as measured by heart rate variability (HRV), and to altered corticolimbic reactivity [33, 34].

In the current study, we hypothesized that functional variation in CHT could impact risk for ADHD and thus examined both the Ile89Val and the 3’SNP in 1) a case-control study utilizing a community sample of DSM-IV validated ADHD subjects versus a healthy control population and 2) a within-family association study involving parent-offspring trios, testing for association with both the primary diagnosis (ADHD), as well as the two common diagnostic subtypes. Here we provide evidence that genetic variation in CHT significantly increases risk for ADHD, particularly for children diagnosed with the Combined subtype.

Methods

Subjects: case-control study

ADHD subjects involved in our initial case-control study were consented and enrolled at Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC), Nashville, TN, USA and the University of Chicago Children’s Hospital, Chicago, IL, USA. Subject ascertainment was performed under a protocol approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both institutions. The VUMC sample consisted of 50 unrelated and 10 affected sib pairs (n = 63 subjects genotyped; 81% male/19% female; 51% Cacasian/12% African American) ranging from 6–17 years of age. The Kiddie-SADS-Present and Lifetime Version [35] was used to determine DSM-IV criteria for ADHD subtypes [36]. The University of Chicago cohort (n = 37 subjects genotyped; 70% male/30% female; 86% Caucasian/14% African American) consisted of a subset of unrelated children who had participated in an earlier pharmacogenetic study [37]. All subjects completed a semi-structured diagnostic interview and met DSM-IV criteria for ADHD. Children were excluded if they carried a diagnosis of autism or other brain disorders such as mental retardation. The Vanderbilt University control cohort consisted of 290 subjects, between 18–45 years of age that displayed no clinically significant abnormality based upon medical history, physical examination and routine laboratory testing.

Subjects: within-family association study

Clinic-referred sample

Four hundred and three children from 251 families were consented and enrolled from two sites, Atlanta, Georgia and Tucson, Arizona, USA (see Suppl Table 1 for details). The Emory University and University of Arizona Institutional Review Boards reviewed and approved the assessment procedures utilized. At the Atlanta site, subjects were recruited through the Center for Learning and Attention Deficit Disorders (CLADD) at the Emory University School of Medicine and the Emory University Psychological Center. Both clinics specialize in the assessment of childhood externalizing disorders such as ADHD, Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD), Conduct Disorder (CD) and learning disorders. At the Tucson site, subjects were recruited through a group psychiatric practice. Probands and their siblings between the ages of 4 and 18 (M = 10.7, SD = 3.9) were then recruited to participate in the current study. Any child previously diagnosed with autism, traumatic brain injury, or neurological conditions (e.g., epilepsy) was excluded from the study, as were children with IQs <75. Any other diagnosis previously assigned to a child remained confidential and did not influence inclusion in the study. Control subjects were also recruited from sites in Atlanta, Georgia and Tucson, Arizona. Subjects recruited at the Atlanta site represent a subsample of the Georgia Twin Registry, a sample of twins born between 1980 and 1991 recruited via birth records from the general population of Georgia. Twin families were originally recruited by mail to participate in a questionnaire-based study of childhood psychopathology. A subset of these families was contacted by phone to participate in a follow-up lab study of temperament and cognitive development that included DNA collection. Subjects from the Tucson site were drawn from the general population.

Parental ratings were obtained whenever possible for each child using the Emory Diagnostic Rating Scale (EDRS) [38], a symptom checklist developed to assess symptoms of major DSM-IV childhood psychiatric disorders such as ADHD, ODD, and CD. Because some children were being treated with medication, parents were asked to rate the status of the child’s symptoms when off medication. Parents rated each symptom on a 0–4 scale, with a score of 0 indicating that the symptom is “not at all” characteristic of the child and a score of 4 indicating that the symptom is “very much” characteristic of the child. Inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive symptom scores were generated by averaging the scores for the 9 items that constitute each symptom dimension. For the purposes of making ADHD and subtype diagnoses, ratings ≥2 for each symptom indicated that a symptom was present. In the case of discrepant parent ratings for a specific symptom, the symptom was considered present if endorsed (i.e., rated ≥2) by the mother when assigning ADHD diagnoses and the mother’s score was then used when creating symptom scales. Consistent with previous studies, mother and father ratings showed moderate agreement (r = .76 for inattentive symptoms and r = .69 for hyperactive-impulsive symptoms) [39]. Questionnaire-based diagnoses of ADHD and its constituent subtypes were assigned by applying DSM-IV symptom thresholds to each of the ADHD symptom dimensions. An earlier study demonstrated that the EDRS yielded diagnostic rates in a control population that were similar to the prevalence rates described in the DSM-IV [40]. The internal consistencies of the 9 hyperactive-impulsive symptoms and the 9 inattentive symptoms were independently evaluated in the clinic-referred and control samples to ensure acceptable reliabilities (values ranged from α = .85–.96).

Genotyping

DNA was collected from either buccal samples or from whole blood and extracted using a commercial DNA isolation kit (Gentra systems, Minneapolis, MN) as previously described [41]. An allelic discrimination assay was performed in the Vanderbilt Center for Human Genetics Research DNA Resources Core using TaqMan® SNP Genotyping Assay reagents (Applied Biosystems, Inc). Four nanograms (ng) of DNA (some samples had been subjected to one round of genomic amplification (Roche) with no evidence of altered SNP calls) was used as template in reactions containing 1X TaqMan® Universal PCR Master Mix and, for CHT Ile89Val (rs1013490), 900 nM forward (5’-TGTACCAGGTTATGGCCTAGCTT-3’) and reverse (5’-ACTGAGATTTGCACTTTCACTTACCT-3’) amplification primers, 200 nM VIC® (5’-CAGGCACCAATTGGATA-3’) and FAM® (5’-AGGCACCAGTTGGATA-3’) dye-labeled probes or, for the CHT 3’SNP (3’SNP, rs333229), forward (5’-GTGGACACACTTCTGGAGATTATACATTT-3’) and reverse (5’-GTCCACGGGCCCTAATATTATATTCT-3’) and 200 nM VIC® (5’- CTCTTAATAATTCCCCCCCACACT-3’) and FAM® (5’- CTCTTAATAATTCACCCCACACT-3’) dye-labeled probes. The 3’SNP has been previously described as a “3’UTR SNP” [33, 34] but our current genomic analyses place the variant 3’ of predicted polyadenylation sites and could not be identified with deposited ESTs. Thermal cycling (95°C for 10 min, followed by 50 cycles of 92°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 1 min) and product detection were accomplished using the ABI 7900HT Real-Time PCR System (ABI).

We conducted quality control analyses of the CHT SNP genotype data in our family samples. The call rate in our sample was 93% for the Ile89Val SNP and 94% for the 3’SNP. Reliability of the genotyping was assessed by examining the concordance of genotypes of twins within MZ twin pairs, in which there were no disagreements between the genotypes for the Ile89Val SNP (an allelic discordance rate = 0%, N = 68 alleles) and only one disagreement for the 3’SNP (an allelic discordance rate = 1.4%, N = 74 alleles). There were no Mendelian errors in the genotyping of the Ile89Val SNP whereas there were 8 errors for the 3’SNP, yielding a Mendelian error rate = 0.9%.

Data analyses

Crosstab analyses using SPSS version 15 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) were conducted for quality control analyses that included measures of genotype reliability and MZ twin agreement for genotypes. Call rates, Mendelian error rates, and exact Hardy Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) tests and p-values were also estimated using the program PEDSTATS [42]. For the case-control studies, genotype call rates were found to be within HWE and significance determined using the χ2-test (results shown below). To protect against the possibility of interpreting a spurious association as substantive, significant results from the case-control analyses were then followed-up in an independent sample using family-based tests of association with the associated alleles from the case-control analyses designated as the ‘risk’ alleles.

Extensions of the Transmission Disequilibrium Test (i.e., TDT) [43] that are applicable to both categorical and continuous variables and tests of moderation [44–47] were used for family-based analyses of association and linkage. Such analyses have the advantage of robustness against possible population stratification effects that may bias the results of traditional case-control comparisons or other population-based analyses of association. A unifying approach to family-based association tests (FBATs) has been developed and implemented in the software packages FBAT and PBAT. Derived from the TDT, the FBAT and PBAT approaches have been extended to incorporate both intact and missing parental genotypes without introducing bias as well as affected and unaffected siblings and extended pedigrees [45, 48–50]. The FBAT and PBAT software packages also allow for the contribution of unaffected control subjects in the calculation of the FBAT test statistic. By specifying an offset equal to the population prevalence of the disorder, the FBAT and PBAT software makes use of genotypic transmissions in case and control subjects by contrasting the number of transmissions of a specific allele in the case population with the number of non-transmissions of that allele in the control population [45]. As such, both case and control subjects can be utilized within a TDT framework. Specifying the offset also serves to minimize the variance of the test statistic and increase statistical power [51]. Thus, the prevalence of the ADHD diagnosis and the respective subtypes in the control sample as assessed by the EDRS were used as offset values in the current study.

We also used a recently developed extension of the TDT [52] to test a priori hypotheses for the contrasts among the diagnostic subtypes. In this method, transmissions of a particular allele from heterozygous parents to children with a subtype of interest are contrasted with transmissions to children who have the other subtypes or who are unaffected. We implemented this test within the FBAT/PBAT analytic framework to test for the association of CHT SNPs with the Inattentive and Combined ADHD subtypes (the Hyperactive-Impulsive subtype was not tested due to small sample size). All of the analyses conducted in FBAT and PBAT yield a Z statistic that was used in hypothesis testing and which was converted into the effect size index R2 (i.e., proportion of the variance accounted for) using the formula Z 2 / N, where N = the number of informative families. Odds Ratios (OR) were calculated by first converting the R2 value into the effect size Cohen’s d using the formula d = (2 * R)/ √(1 - R2)[53], and then calculating an OR using the formula e(1.81 * d) described by Chinn [54].

Results

Case-control study of CHT SNPs in ADHD

Our initial evaluation of the association of CHT SNPs in ADHD was performed as a simple case-control design with affected subjects drawn from prior Vanderbilt and University of Chicago studies [9, 11, 37]. The mean age of the Vanderbilt/Chicago sample was 10.5 ± 0.3 years and was 76% male, 24% female with mostly Caucasian (81%) versus African-American (19%) subjects. Controls subjects were drawn from a panel of healthy controls with no medical diagnoses, originally recruited for cardiovascular studies. The mean age of the control sample was 28 ± 7.7 years and was 42% male, 58% female with both Caucasian (44%) and African-American (56%) subjects. Owing to significant ethnic variation evident in the CHT Val89 variant (NCBI dbSNP, build 129; refSNP ID: rs1012940; GenBank accession no.: NT005224.10), we restricted our case-control analyses to the Caucasian subset of this panel.

Genotypes for both Ile89Val and 3’SNP polymorphisms were reliably obtained and found to be in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium in both case (Ile89Val, p = 0.99; 3’UTR, P = 0.75) and control groups (Ile89Val, P = 0.52; 3’SNP, P = 0.93). The minor allele for the Val89 marker has been previously reported at an allele frequency of 6% in a nonclinical sample of Ashkenazi Jewish subjects [29], which is identical to the allele frequency we obtained in our Caucasian control samples (Table 1). The CHT 3’SNP major allele has been reported as 77% in healthy Caucasians [33] and was also comparable to our findings with Caucasian control DNAs (73%, Table 1). Independent studies indicate that the 3’SNP major allele and the Val89 minor allele are associated with reduced choline uptake or cholinergic function [29, 34]. In the Vanderbilt/Chicago ADHD panel, the allele frequency for the CHT 3’SNP major allele was slightly elevated (79%), though this change did not reach statistical significance. Further examination of the CHT 3’SNP allele frequencies in Caucasian and Caucasian male-only groups versus matched controls showed a significant shift in allele distribution that did not differ between the diagnostic subtypes (Caucasian, 84% major allele, P = 0.008; Caucasian-male only, 87%, P = 0.004). These findings support the association of reduced cholinergic tone with a diagnosis of ADHD in Caucasian subjects. Similarly, the allele frequency of the hypomorphic Val89 CHT variant were significantly elevated (12%) compared to that (6%) found in our healthy controls (P = 0.023). Further examination of Val89 allele frequencies in Caucasian or Caucasian male-only groups versus matched controls revealed an even greater increase in both the Inattentive (Caucasian, 15%; P = 0.03; Caucasian-male only, 17%; P = 0.02) and Combined (Caucasian, 14%; P = 0.03; Caucasian-male only, 15%; P = 0.03) subtypes (Table 1).

Family-based association analyses of CHT SNPs in ADHD

The study sample used for our within-family association analyses represents an expansion of that reported in previous publications (see Suppl Table 1 for complete sample characteristics) [38, 55]. Our sample comprised 269 boys (67%) and 134 (33%) girls, with an ethnic background of 78% Caucasian, 10% African-American, 2% Hispanic, 1% Asian, and 8% of mixed ethnicity. Two hundred of the 251 probands met criteria for a DSM-IV ADHD diagnosis with 70 children (35%) diagnosed with the predominately Inattentive subtype, 12 (6%) with the predominately Hyperactive-Impulsive subtype, and 118 (59%) with the Combined subtype. These subtype prevalence rates are consistent with those reported in the literature which indicate that the Combined subtype is 1.5 to 2 times more common than the Inattentive subtype in clinic-referred samples [56, 57]. Thirty-six of the 152 siblings that participated in the study met criteria for ADHD. Thirteen (36%) were diagnosed with the predominately Inattentive subtype, 10 (28%) with the predominately Hyperactive-Impulsive subtype, and 13 (36%) with the Combined subtype.

As shown in Suppl Table 1, control children differed from clinic-referred children with respect to age, gender, and ethnicity (P-values < .05). Control subjects ranged in age from 6 to 18 years (M = 12.9, SD = 2.6), included 138 boys (58%) and 98 girls (42%), and their ethnic background was 92% Caucasian, 2% African-American, 2% Asian, and 4% Hispanic. Because control subjects were drawn from the general population, a certain percentage of these children were expected to exhibit clinically significant symptoms of ADHD. Forty-five met criteria for the ADHD diagnosis. Twenty-four (53%) were diagnosed with the predominately Inattentive subtype, 8 (18%) with the predominately Hyperactive-Impulsive subtype, and 13 (29%) with the Combined subtype. These subtype prevalence rates are consistent with those reported in the literature that indicate the Inattentive subtype to be approximately twice as common as the Combined subtype in community samples [58, 59]. Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) was evaluated, excluding individuals of African-American ethnic background given the pronounced differences in allele and genotype frequencies for CHT SNPs between individuals of European and African descent (International HapMap Project, 2005). There was no significant departure from HWE for either the Ile89Val (P = 1.00) or the 3’SNP (P = .066) in founders.

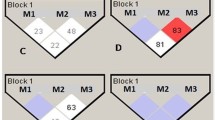

As shown in Tables 2 and 3, in our family-based analyses of association of the overall ADHD diagnosis with the Ile89Val or 3’SNP using FBAT, we found no evidence for association with either SNP across additive, dominant, or recessive genetic models, regardless of whether only affected cases were analyzed or whether affected cases were contrasted with unaffected controls (i.e., the minimum P = 0.347 for the 3’SNP under a dominant model contrasting transmission in affected cases versus unaffected controls). As shown in Table 2, however, there was a significant association between the Val89 allele and the Combined subtype, which was strongest under additive and dominant models when the Combined subtype was contrasted with no diagnosis and all other subtypes (additive: Z = 2.19, one-tailed P = 0.014, R2 = .09, OR = 3.16; dominant: Z = 1.97, one-tailed P = 0.024, R2 = .07 OR = 2.79).

We next conducted similar family-based association analyses of ADHD and its diagnostic subtypes with haplotypes comprising both CHT SNPs (Table 4). Linkage disequilibrium between the two markers was virtually absent (D’ = .04. R2 = .01). For the overall diagnosis of ADHD, as well as the Combined and Inattentive subtypes, we conducted an omnibus test of association for all haplotypes as well as a targeted test of and when significant, followed this up by determining which specific haplotype was responsible for the observed association the subtype comprising all possible haplotypes. In all haplotype tests, we contrasted transmissions in ADHD cases versus unaffected controls or transmissions in the Combined or Inattentive subtypes versus unaffected controls and all other subtypes. All of the haplotype tests for either the ADHD diagnosis or the Inattentive subtype were non-significant. In contrast, the omnibus tests yielded a significant association with the Combined subtype under an additive model (Z = 8.48, P = .037) and a trend towards an association under a dominant model (Z = 8.16, P = 0.086) with the haplotype comprising both Ile89Val and 3’SNP minor alleles showing the strongest associations (additive model: Z = 2.65, P = 0.008, R2 = .048, OR = 2.25; dominant model: Z = 2.65, P = 0.008, R2 = .069, OR = 2.68).

Discussion

To our knowledge, no investigations of CHT gene variation in the context of ADHD have been reported. Possibly, modest alterations in CHT expression or function might have no detectible influence on physiology and behavior. However, studies with CHT heterozygous knockout mice reveal a significant reduction in brain ACh levels, as well as reduced motor endurance and locomotor responsiveness to cholinergic antagonist administration [31]. Human studies reveal two CHT polymorphisms with a likely functional impact on cholinergic signaling. The Val89 variant exhibits reduced choline transport function compared to the Ile89 variant in transfected cells [29] and has been associated with major depression [32]. A second purportedly functional SNP, located 3’ of predicted CHT polyadenylation sites, is associated with altered autonomic cholinergic tone as well as cortical reactivity and depression [33, 34]. Given the prominent role of thalamic and cortical cholinergic signaling for sensory gating and sustained attention [60, 61], we hypothesized that one or more, or both, of the CHT variants might contribute risk for ADHD. Indeed, with our Vanderbilt/Chicago ADHD cohort, we observed an increased frequency of the Val89 CHT hypomorph as compared to published allele frequencies and our own healthy control population [29]. As a check on the allele frequencies our healthy control panel, we also genotyped the Ile89Val polymorphism on a commercial panel (Coriell) and found a comparable frequency for Caucasians (9%) and Caucasian males (8%), significantly below the allele frequency of our ADHD subjects. Depending on gender, the elevation we observed in Val89 frequency in our ADHD subjects is equivalent to, or above, that which we reported in a major depression cohort [32]. Depression and ADHD exhibit significant comorbidity [62, 63]. The higher rate of suicide in ADHD subjects exhibiting depression [64, 65] warrants an assessment of whether altered cholinergic tone represents a common pathway to ADHD/depression comorbidity.

Although we made an effort to constrain our case-control analysis by ethnicity and gender, such designs are subject to unknown population stratifications that can lead to false positive (or negative) results. We thus sought to gain further insight into the impact of the CHT gene variants in ADHD via within-family association analyses of both alleles individually and in combination using a parent-offspring trio design in a large, more well-defined ADHD cohort. We did not constrain our analyses by ethnicity or gender in transmission studies to maintain the largest sample size possible and increase power. We observed preferential transmission of the CHT 89Val allele with the Combined subtype of ADHD using both additive and dominant models. These findings indicate that having 1 or 2 copies of the risk allele increases the likelihood of a Combined ADHD diagnosis in an additive fashion. Although other coding variants in neurotransmitter transporters are known to act dominantly that could be explained by dominant-negative interactions [66–68], similar information is not yet available for the CHT Val89 variant. To date, the Val89 CHT variant has only been studied in vitro in a parallel comparison with the Ile89 variant, and not following co-expression studies that could test the possibility of homo-oligomerization, as seen for other transporters [69–71]. Clearly, further in vitro studies are needed to establish the genetic model underlying the impact of the Val89 SNP in ADHD.

The preferential transmission of the CHT Val89 hypomorph to the Combined subtype in the additive model may reflect the importance of cholinergic transmission in modulating fundamental aspects of both motor control and attention [72, 73]. On neuroanatomical grounds, patients with reduced CHT activity should have cholinergic deficits at both cortical and subcortical levels which could produce both inattentive and hyperactivity symptoms. Cholinergic interneurons within the striatum participate in extrapyramidal motor control [74] and alterations in the balance of cholinergic/dopaminergic signaling in this nucleus is implicated in a spectrum of motor abnormalities from hyperactivity and motor tics to dystonia and Parkinson’s disease [75]. Consistent with these ideas, disruptions in cholinergic transmission produce deficits in attention and can trigger hyperactivity [76, 77]. Experimentally-induced cortical and striatal reductions in ACh content produce hyperlocomotion and other motor dysfunctions [78, 79]. Similarly, mice lacking the M1 muscarinic receptor exhibit an increase in locomotor activity and altered dopamine signaling [77]. Consistent with our findings on CHT, Lee et al. recently reported an association of two markers in exon 2 and intron 2 of the α4 subunit of the nAChR that are selectively transmitted to subjects with the Combined subtype of ADHD [80]. Currently, medications for ADHD predominantly target catecholaminergic signaling and are not prescribed differently based on diagnostic subtype. Our findings, if reproduced, encourage further consideration of cholinergic agonist therapy as well as evaluation of whether cholinergic modulation is most beneficial for subjects presenting with both motor and attention symptoms.

Our studies also explored a potential impact of the 3’SNP variant in CHT. Although the overall association of the 3’SNP minor allele to ADHD in our case-control paradigm was non-significant, a significant increase in the major allele was evident when our data set was limited to male Caucasians. We do not know the basis for the ethnicity and gender effects on allele frequencies, nor whether they relate to the male predominance in ADHD diagnoses. Presently, the functional impact of this 3’SNP at the level of CHT gene expression is unknown, but may serve as a downstream repressor of transcription [81] or be in linkage disequilibrium with one or more other functional variants. Alternatively, the variant may be in linkage disequilibrium with another variant in or near the CHT gene impacting transporter expression. Healthy patients carrying the 3’SNP minor allele demonstrate an increase heart rate variability that is associated with increased parasympathetic tone [33]. Our case-control findings of a decrease in the 3’SNP minor allele is, therefore, most consistent with reduced cholinergic function? in ADHD.

In our within-family association study, although we observed no association between the overall ADHD diagnosis or any diagnostic subtype with the 3’SNP on its own, we detected a highly significant association of a two locus haplotype comprised of the CHT Val89 allele and the 3’SNP minor allele. This finding is somewhat surprising given that these two alleles are predicted to support reduced Val89) and elevated (3’SNP T allele) cholinergic tone, respectively. These two polymorphisms are not in linkage disequilibrium and thus it is possible that at risk subjects may carry both minor alleles on the same transcript. If the CHT Val89 protein variant exhibits a dominant-negative action on Ile89 protein, elevations in the Val89 protein made possible by elevations in CHT mRNA levels driven by the 3’SNP minor allele could explain our family-based association findings. Clearly, however, such conclusions are speculative given 1) the lack of study of oligomerization of CHT proteins, 2) the uncertain mechanistic status of the 3’SNP, and 3) the limited power of our analysis due to inherent reductions in sample size arising with selection of multiple gene variants, as well as subdivision of diagnoses by phenotypic subclasses.

A number of reports have described genome wide linkage or association studies in ADHD [82–85]. Many loci do not replicate across studies, though chromosomal regions 5p13, 14q12 and 17p11 have been implicated in multiple studies [86, 87]. The SLC5A7 gene is located on chromosome 2q12, and has not to date been identified in published genome wide studies in ADHD. Genome wide studies face daunting power issues due to large number of tests performed. Our study was focused on CHT from the neurobiological perspective of alterations in cholinergic tone contributing to motor and cognitive behavioral domains altered in ADHD. Future studies with a larger number of markers in and adjacent to the SLC5A7 locus may provide further insight into the contribution of the CHT gene to ADHD.

Despite the potential of the reported findings to further our understanding of the relation between the CHT gene and ADHD, it should be noted that a number of statistical tests were conducted in the present study, but due to the modest sample size, corrections were not made for multiple testing. Nonetheless, specific steps were taken to protect against interpreting a spurious association as substantive. The most stringent step was the inclusion of two independent samples and two complementary research designs and analytic methods, thus providing a follow-up sample and more rigorous family-based association tests with which to confirm the original case-control association findings. Thus for all analyses conducted in the follow-up sample, directional predictions were made regarding potential associations between the CHT gene SNPs and ADHD phenotypes to ensure that only associations with the alleles identified in the case-control analyses were interpreted as significant in the follow-up analyses. Despite the precautions taken, some possibility that the reported findings represent a spurious association remains, and future studies replicating these results are necessary.

In summary, the current study provides evidence of both association and preferential transmission of the CHT Val89 variant to the ADHD Combined subtype, alone and in combination with the minor allele of the CHT 3’SNP polymorphism. Future studies, besides seeking further replication on independent ADHD samples, should examine directly the functional role of these variants on cholinergic neurotransmission in humans in vivo as well as explore the Combined subtype as a preferential subgroup for cholinergic therapeutics.

References

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Assocation; 2004. [test revision[. 2004.

Caballero J, Nahata MC. Atomoxetine hydrochloride for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clin Ther. 2003;25:3065–83.

Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T. Nonstimulant treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004;27:373–83.

Faraone SV, Doyle AE. The nature and heritability of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2001;10:299–316. viii–ix.

Mick E. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17:261–84.

Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Goralnick JJ, Holmgren MA, et al. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:1313–23.

Faraone SV, Khan SA. Candidate gene studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(Suppl 8):13–20.

Prince J. Catecholamine dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an update. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:S39–45.

Mazei-Robison MS, Couch RS, Shelton RC, Stein MA, Blakely RD. Sequence variation in the human dopamine transporter gene in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:724–36.

Kim JJ, Shih JC, Chen K, Chen L, Bao S, Maren S, et al. Selective enhancement of emotional, but not motor, learning in monoamine oxidase A-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:5929–33.

Kim CH, Hahn MK, Joung Y, Anderson SL, Steele AH, Mazei-Robinson MS, et al. A polymorphism in the norepinephrine transporter gene alters promoter activity and is associated with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19164–9.

Tzavara ET, Bymaster FP, Overshiner CD, Davis RJ, Perry KW, Wolff M, et al. Procholinergic and memory enhancing properties of the selective norepinephrine uptake inhibitor atomoxetine. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:187–95.

Rowe DL, Hermens DF. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: neurophysiology, information processing, arousal and drug development. Expert Rev Neurother. 2006;6:1721–34.

Doody RS. Current treatments for Alzheimer’s disease: cholinesterase inhibitors. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 9):11–7.

Kent L, Green E, Holmes J, Thapar A, Gill M, Hawi Z, et al. No association between CHRNA7 microsatellite markers and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet. 2001;105:686–9.

Calabresi P, Centonze D, Gubellini P, Pisani A, Bernardi G. Acetylcholine-mediated modulation of striatal function. Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:120–6.

Kaneko S, Hikida T, Watanabe D, Ichinose H, Nagatsu T, Kreitman RJ, et al. Synaptic integration mediated by striatal cholinergic interneurons in basal ganglia function. Science. 2000;289:633–7.

Sarter MF, Bruno JP. Cognitive functions of cortical ACh: lessons from studies on trans-synaptic modulation of activated efflux. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:217–21.

Perry E, Walker M, Grace J, Perry R. Acetylcholine in mind: a neurotransmitter correlate of consciousness? Trends Neurosci. 1999;22:273–80.

Sarter M, Hasselmo ME, Bruno JP, Givens B. Unraveling the attentional functions of cortical cholinergic inputs: interactions between signal-driven and cognitive modulation of signal detection. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:98–111.

Hasselmo ME, McGaughy J. High acetylcholine levels set circuit dynamics for attention and encoding and low acetylcholine levels set dynamics for consolidation. Prog Brain Res. 2004;145:207–31.

Todd RD, Lobos EA, Sun LW, Neuman RJ. Mutational analysis of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha 4 subunit gene in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: evidence for association of an intronic polymorphism with attention problems. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:103–8.

Kent L, Middle F, Hawi Z, Fitzgerald M, Gill M, Feehan C, et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha4 subunit gene polymorphism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2001;11:37–40.

Okuda T, Haga T. Functional characterization of the human high-affinity choline transporter. FEBS Lett. 2000;484:92–7.

Ferguson SM, Savchenko V, Apparsundaram S, Zwick M, Wright J, Heilman CJ, et al. Vesicular localization and activity-dependent trafficking of presynaptic choline transporters. J Neurosci. 2003;23:9697–709.

Ferguson SM, Blakely RD. The choline transporter resurfaces: New roles for synaptic fesicles? Mol Interv. 2004;4:22–37.

Atweh S, Simon JR, Kuhar MJ. Utilization of sodium-dependent high affinity choline uptake in vitro as a measure of the activity of chloinergic neurons in vivo. Life Sci. 1975;17:1535–44.

MV AS, Parikh V, Kozar R, Sarter M. Increased capacity and density of choline transportes situated in synaptic membranes of the right medial prefrontal cortex of attentional task-performing rats. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3851–6.

Okuda T, Okamura M, Kaitsuka C, Haga T, Gurwitz D. Single nucleotide polymorphism of the human high affinity choline transporter alters transport rate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:45315–22.

Apparsundaram S, Ferguson SM, George AL Jr, Blakely RD. Molecular cloning of a human, hemicholinium-3-sensitive choline transporter. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;276:862–7.

Bazalakova MH, Wright J, Schneble EJ, McDonald MP, Heilman CJ, Levey AI, et al. Deficits in acetylcholine homeostasis, receptors and behaviors in choline transporter heterozygous mice. Genes Brain Behav. 2007;6:411–24.

Hahn MK, Blackford JU, Haman K, Mazei-Robison M, English BA, Prasad HC, et al. Multivariate permutation analysis associates multiple polymorphisms with subphenotypes of major depression. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:487–95.

Neumann SA, Lawrence EC, Jennings JR, Ferrell RE, Manuck SB. Heart rate variability is associated with polymorphic variation in the choline transporter gene. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:168–71.

Neumann SA, Brown SM, Ferrell RE, Flory JD, Manuck SB, Hariri AR. Human choline transporter gene variation is associated with corticolimbic reactivity and autonomic-cholinergic function. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1155–62.

Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, et al. Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–8.

Ambrosini PJ. Historical development and present status of the schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children (K-SADS). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:49–58.

Stein MA, Waldman ID, Sarampote CS, Seymour KE, Robb AS, Conlon C, et al. Dopamine transporter genotype and methylphenidate dose response in children with ADHD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;30:1374–82.

Waldman I, Rowe D, Abramowitz A, Kozel S, Mohr J, Sherman S, et al. Association and linkage of the dopamine transporter gene and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children: heterogeneity owing to diagnostic subtype and severity. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1767–76.

Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, Howell CT. Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychol Bull. 1987;101:213–32.

Waldman ID, Rowe DC, Abramowitz A, Kozel ST, Mohr JH, Sherman SL, et al. Association and linkage of the dopamine transporter gene and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children: heterogeneity owing to diagnostic subtype and severity. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:1767–76.

Mazei-Robison MS, Couch RS, Shelton RC, Stein MA, Blakely RD. Sequence variation in the human dopae transporter gene in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Neuropharmacology. 2005.

Wigginton JE, Abecasis GR. PEDSTATS: descriptive statistics, graphics and quality assessment for gene mapping data. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3445–7.

Spielman RS, McGinnis RE, Ewens WJ. Transmission test for linkage disequilibrium: the insulin gene region and insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (IDDM). Am J Hum Genet. 1993;52:506–16.

Dudbridge F. Pedigree disequilibrium tests for multilocus haplotypes. Genet Epidemiol. 2003;25:115–21.

Lange C, Laird NM. On a general class of conditional tests for family-based association studies in genetics: the asymptotic distribution, the conditional power, and optimality considerations. Genet Epidemiol. 2002;23:165–80.

Waldman ID, Robinson BF, Feigon SA. Linkage disequilibrium between the dopamine transporter gene (DAT1) and bipolar disorder: extending the transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) to examine genetic heterogeneity. Genet Epidemiol. 1997;14:699–704.

Waldman ID, Robinson BF, Rowe DC. A logistic regression based extension of the TDT for continuous and categorical traits. Ann Hum Genet. 1999;63:329–40.

Lange C, Blacker D, Laird NM. Family-based association tests for survival and times-to-onset analysis. Stat Med. 2004;23:179–89.

Lange C, DeMeo D, Silverman EK, Weiss ST, Laird NM. Using the noninformative families in family-based association tests: a powerful new testing strategy. Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73:801–11.

Rabinowitz D, Laird N. A unified approach to adjusting association tests for population admixture with arbitrary pedigree structure and arbitrary missing marker information. Hum Hered. 2000;50:211–23.

Laird NM, Cuenco KT. Regression methods for assessing familial aggregation of disease. Stat Med. 2003;22:1447–55.

Epstein MP, Waldman ID, Satten GA. Improved association analyses of disease subtypes in case-parent triads. Genet Epidemiol. 2006;30:209–19.

Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1991.

Chinn S. A simple method for converting an odds ratio to effect size for use in meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2000;19:3127–31.

Rowe D, Stever C, Giedinghagen L, Gard J, Cleveland H, Terris S, et al. Dopamine DRD4 receptor polymorphism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 1998;3:419–26.

Faraone SV, Biederman J, Weber W, Russell RL. Psychiatric, neuropsychological, and psychosocial features of DSM-IV subtypes of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Results from a clinically referred sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37:185–93.

Lahey BB, Applegate B, McBurnett K, Biederman J, et al. DMS-IV field trials for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1673–85.

Baumgaertel A, Wolraich ML, Dietrich M. Comparison of diagnostic criteria for attention deficit disorders in a German elementary school sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:629–38.

Wolraich ML, Hannah JN, Pinnock TY, Baumgaertel A, et al. Comparison of diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in a county-wide sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:319–24.

Sarter M, Bruno JP. Cortical cholinergic inputs mediating arousal, attentional processing and dreaming: differential afferent regulation of the basal forebrain by telencephalic and brainstem afferents. Neuroscience. 2000;95:933–52.

Kobayashi Y, Isa T. Sensory-motor gating and cognitive control by the brainstem cholinergic system. Neural Netw. 2002;15:731–41.

Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87.

Daviss WB. A review of co-morbid depression in pediatric ADHD: etiology, phenomenology, and treatment. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2008;18:565–71.

James A, Lai FH, Dahl C. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and suicide: a review of possible associations. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2004;110:408–15.

Galera C, Bouvard MP, Encrenaz G, Messiah A, Fombonne E. Hyperactivity-inattention symptoms in childhood and suicidal behaviors in adolescence: the Youth Gazel Cohort. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2008;118:480–9.

Sutcliffe JS, Delahanty RJ, Prasad HC, McCauley JL, Han Q, Jiang L, et al. Allelic heterogeneity at the serotonin transporter locus (SLC6A4) confers susceptibility to autism and rigid-compulsive behaviors. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:265–79.

Hahn MK, Robertson D, Blakely RD. A mutation in the human norepinephrine transporter gene (SLC6A2) associated with orthostatic intolerance disrupts surface expression of mutant and wild-type transporters. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4470–8.

Shannon JR, Flattem NL, Jordan J, Jacob G, Black BK, Biaggioni I, et al. Orthostatic intolerance and tachycardia associated with norepinephrine-transporter deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:541–9.

Sitte HH, Farhan H, Javitch JA. Sodium-dependent neurotransmitter transporters: oligomerization as a determinant of transporter function and trafficking. Mol Interv. 2004;4:38–47.

Schmid JA, Just H, Sitte HH. Impact of oligomerization on the function of the human serotonin transporter. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:732–6.

Kocabas AM, Rudnick G, Kilic F. Functional consequences of homo- but not hetero-oligomerization between transporters for the biogenic amine neurotransmitters. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1513–20.

Potter AS, Newhouse PA, Bucci DJ. Central nicotinic cholinergic systems: A role in the cognitive dysfunction in Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder? Behavioural Brain Research. 2006;175:201–11.

Vakalopoulos C. Neurocognitive deficits in major depression and a new theory of ADHD: a model of impaired antagonism of cholinergic-mediated prepotent behaviours in monoamine depleted individuals. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68:210–21.

Pisani A, Bernardi G, Ding J, Surmeier DJ. Re-emergence of striatal cholinergic interneurons in movement disorders. Trends Neurosci. 2007;30:545–53.

Miller AD, Blaha CD. Nigrostriatal dopamine release modulated by mesopontine muscarinic receptors. Neuroreport. 2004;15:1805–8.

Sarter M, Parikh V. Choline transporters, cholinergic transmission and cognition. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:48–56.

Gerber DJ, Sotnikova TD, Gainetdinov RR, Huang SY, Caron MG, Tonegawa S. Hyperactivity, elevated dopaminergic transmission, and response to amphetamine in M1 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:15312–7.

Carta M, Stancampiano R, Tronci E, Collu M, Usiello A, Morelli M, et al. Vitamin A deficiency induces motor impairments and striatal cholinergic dysfunction in rats. Neuroscience. 2006;139:1163–72.

Mattsson A, Pernold K, Ogren SO, Olson L. Loss of cortical acetylcholine enhances amphetamine-induced locomotor activity. Neuroscience. 2004;127:579–91.

Lee J, Laurin N, Crosbie J, Ickowicz A, Pathare T, Malone M, et al. Association study of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha4 subunit gene, CHRNA4, in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Genes Brain Behav. 2008;7:53–60.

Chen JM, Ferec C, Cooper DN. A systematic analysis of disease-associated variants in the 3’ regulatory regions of human protein-coding genes II: the importance of mRNA secondary structure in assessing the functionality of 3’ UTR variants. Hum Genet. 2006;120:301–33.

Lasky-Su J, Neale BM, Franke B, Anney RJ, Zhou K, Maller JB, et al. Genome-wide association scan of quantitative traits for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder identifies novel associations and confirms candidate gene associations. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1345–54.

Franke B, Neale BM, Faraone SV. Genome-wide association studies in ADHD. Hum Genet. 2009.

Neale BM, Lasky-Su J, Anney R, Franke B, Zhou K, Maller JB, et al. Genome-wide association scan of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1337–44.

Rommelse NN, Arias-Vasquez A, Altink ME, Buschgens CJ, Fliers E, Asherson P, et al. Neuropsychological endophenotype approach to genome-wide linkage analysis identifies susceptibility loci for ADHD on 2q21.1 and 13q12.11. Am J Hum Genet. 2008;83:99–105.

Zhou K, Dempfle A, Arcos-Burgos M, Bakker SC, Banaschewski T, Biederman J, et al. Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage scans of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2008;147B:1392–8.

Arcos-Burgos M, Castellanos FX, Pineda D, Lopera F, Palacio JD, Palacio LG, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a population isolate: linkage to loci at 4q13.2, 5q33.3, 11q22, and 17p11. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:998–1014.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the families whose provision of DNA made this research possible. Additionally, we thank Tammy Jessen, Jane Wright, Qiao Han and Tracy Moore-Jarrett for excellent lab oversight. The studies described were supported by an American Heart Association Award 0715120B (B.A.E) and NIH Awards MH076018 (M.K.H.), MH072083 (I.R.G.), MH01818 (I.D.W.), K24MHO1823 (M.A.S), HL56693 (R.D.B.), and MH073159 (R.D.B.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Brett A. English, Maureen K. Hahn and Ian R.Gizer have contributed equally to this study.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Table 1

Sample characteristics for the clinic-referred and control samples used for CHT polymorphism transmission analysis (DOC 70 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

English, B.A., Hahn, M.K., Gizer, I.R. et al. Choline transporter gene variation is associated with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Neurodevelop Disord 1, 252–263 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11689-009-9033-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11689-009-9033-8