Abstract

Background

The benefits of the various therapeutic options for the treatment of subacromial impingement syndrome are a topic of ongoing debate. Several studies on the subject are insufficiently evidence-based, with many other studies being considered controversial by members of the field. Nevertheless, a general opinion against surgical interventions is developing in the media in reference to these systematic reviews and meta-analyses based on insufficiently differentiated literature.

Aim of the study

This article provides an overview of the literature and examines the outcome after arthroscopic subacromial decompression compared with conservative therapy or diagnostic arthroscopy and bursectomy.

Conclusion

The outcome for patients treated with conservative therapy or subacromial decompression who explicitly suffered from mechanical outlet impingement (MOI) or mechanical non-outlet impingement (MNOI) has not yet been studied. The main problem concerning almost all published studies is that they are based on a mixture of pathologies. It seems likely that especially patients with a mechanical, and therefore structural, narrowing of the subacromial space can profit more from surgical management than patients with unspecific subacromial pain. Differentiation between the pathologies is crucial for the correct treatment decision, not only for the reduction of symptoms, but most importantly for the preservation of the supraspinatus tendon.

Zusammenfassung

Hintergrund

Die Therapie des Impingementsyndroms des Schultergelenks gibt in den letzten Jahren immer wieder Anlass zu Diskussionen. Die Studienlage zu diesem Thema ist kontrovers und zu großen Teilen nicht ausreichend evidenzbasiert. Dennoch dienen vorrangig in den letzten Jahren publizierte systematische Reviews und Metaanalysen auf Grundlage dieser wenig differenzierten Literatur als Basis einer sich in den Medien verbreitenden pauschalen Empfehlung gegen chirurgische Interventionen.

Zielsetzung

Es wurde ein Übersichtsartikel verfasst, um randomisierte Studien zum Outcome der arthroskopischen, subakromialen Dekompression und deren Vergleich mit konservativer Therapie oder diagnostischer Arthroskopie und Bursektomie zu analysieren und differenziert zu betrachten.

Zusammenfassung

Das Outcome nach konservativer Therapie oder subakromialer Dekompression bei Patienten, die explizit unter einem subakromialen Impingement im Sinne eines mechanischen Outlet-Impingements (MOI) leiden, wurde bisher nicht so dezidiert untersucht. Die publizierte Literatur stützt sich ausschließlich auf äußerst grob gefasste Indikationsspektren. Es ist naheliegend und denkbar, dass insbesondere Patienten mit einer mechanischen, strukturellen Enge von einer operativen Therapie mittels subakromialer Dekompression deutlich mehr profitieren als Patienten mit einem unspezifischen subakromialen Schulterschmerz. Die Differenzierung der zugrunde liegenden Pathologie ist essenziell für die Therapieentscheidung, nicht nur für die Beschwerdereduktion, sondern auch für den langfristigen Erhalt der Supraspinatussehne.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

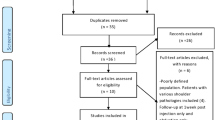

The relative benefits of the various therapeutic options for the treatment of impingement syndrome of the shoulder joint are a topic of ongoing debate. The main problem concerning almost all published studies is that they are based on a mixture of pathologies and the inclusion criteria are not homogenous. Several unspecific studies merge the pathology of subacromial impingement syndrome with subacromial pain syndrome, and do not differentiate the outcomes according to the different pathologies. A small number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) are more thorough and are therefore a focus of interest. These trials, and a number of review articles, question the indication for surgery in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome. It is therefore of great importance to elucidate the correct and appropriate pathway for the treatment of these patients. This article discusses several randomized trials studying the outcomes of surgical subacromial decompression compared to conservative therapy or sham surgery. The authors included prospective randomized trials, systematic reviews and meta-analyses listed in Pubmed in the last 30 years that compared either surgical and/or conservative treatment to other treatment options of subacromial impingement/subacromial pain syndrome. In total, 12 studies were included in the detailed analysis (shown in Table 1).

Aetiology and terminology

The terms used to describe shoulder-associated pathologies are, in themselves, a matter of ongoing debate: for example, the use of subacromial impingement syndrome (SIS) or subacromial pain syndrome (SAPS) as opposed to mechanical outlet impingement (MOI) or mechanical non-outlet impingement (MNOI) [7, 11]. The pathology of SIS has been established since the 1970s and describes entrapment of the supraspinatus tendon, the subacromial bursa or the long head of biceps tendon between the humeral head and coracoacromial bone. SIS therefore includes functional pathologies of the soft tissue [5, 18, 28]. In order to respect the content of all terminologies, and to refer to possibly different reasons for subacromial impingement, the name subacromial pain syndrome was later introduced [7]. This definition was initially published in Dutch guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of SAPS and summarizes atraumatic, mostly unilateral pathologies that lead to shoulder pain that increases during abduction of the joint. Subsequently, SAPS has a descriptive character and is somewhat nonspecific in naming the underlying pathology.

In order to properly address subacromial pathologies ,it is important to differentiate between primary or secondary subacromial impingement [14]. Primary impingement results from structural changes in the subacromial space due to mechanical impingement. This can follow on from anterolateral acromial spurs, osteophytes under the acromioclavicular (AC) joint or displaced healing of fractures of the greater tuberosity and is usually referred to as mechanical outlet impingement ([27]; Fig. 1). Apart from that, calcifying tendinitis or hypertrophic bursal tissue can decrease the subacromial space from the caudal side; this is referred to as mechanical non-outlet impingement [14]. Secondary impingement summarizes the muscular dysfunctions that lead to misalignment of the humeral head or glenohumeral hyperlaxity [14].

The pathology of mechanical impingement (MOI and/or MNOI) is therefore based on a defined structural pathology, whereas SIS and SAPS describe summaries of symptoms of different pathologies in the subacromial space. The descriptions are also shown in Table 2.

The informative value of clinical examination

Different clinical tests have been established in the diagnosis of impingement syndrome. Well-established tests include the Hawkins–Kennedy test, Neer test and the painful arc test. It is worth noting that the specific pathology cannot be identified on clinical examination alone, i.e. SAPS/SIS and MOI/MNOI cannot be differentiated. Kappe et al. studied the predictive value of the different clinical impingement tests for a good outcome after subacromial decompression [16]. Patients that were Hawkins test-positive in the neutral position, as well as Neer test- and Jobe test-positive (empty can), achieved a significantly better result in the Constant score and Western Ontario Rotator Cuff (WORC) index postoperatively (even though the Jobe test was originally described for detecting pathologies of the supraspinatus tendon). Furthermore, an even better outcome was reached if four or more different impingement tests were positive (including the Yergasonʼs test and Speedʼs test, which were originally designed to clinically examine the long head of the biceps tendon). In 2014, Singh et al. established a preoperative scoring system (PrOS) to help in the selection of patients that would benefit from surgical intervention [33]. The authors found a positive correlation between the following parameters and a positive outcome after subacromial decompression: pain during overhead activity, duration of pain longer than 6 months, ongoing problems despite continuous physiotherapy, positive Hawkins sign, radiological signs of subacromial impingement (sclerosis and/or osteophytes under the acromion or on the greater tuberosity) and improvement for at least 1 week following subacromial corticoid injection. According to these parameters, a maximum of six points can be reached in the PrOS. Patients with a PrOS of five and more points show a significantly better outcome 3 months after surgery than patients with less than five points. Magaji et al. also studied which patients will achieve a good outcome after subacromial decompression [26]. Patients that were positive for four indication criteria (temporary decrease in symptoms after steroid injection, positive testing for painful arc and Hawkins test, radiological signs of impingement [the same as used by Singh et al.]) showed a better outcome after subacromial decompression than did patients with less than four criteria points. An overview of the prognostic parameters is shown in Table 3.

Imaging

In 2017, the German Society of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery (DVSE) published guidelines on imaging in patients with subacromial impingement [6]. The society recommended standard radiographs of the painful shoulder in true anteroposterior (AP) and outlet view. In addition, a radiograph in axillary view was also indicated to be potentially helpful, wherein an acromion slope according to Bigliani’s classification, the acromion tilt, acromion index or the lateral acromial angle could be determined, potentially showing signs of MOI [1]. Figure 1 demonstrates pathological changes in an outlet radiograph in MOI patients. Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) could also be included if relevant. Although ultrasound of the shoulder may help in the diagnosis of subacromial bursitis or pathologies of the rotator cuff, the results are dependent on the examiner. MRI examination is important to rule out differential diagnoses of the clinical symptoms. Especially in cases with a normal radiograph, signs of MNOI (such as subacromial bursitis, rotator cuff pathologies or ruptures, hypertrophic coracoacromial ligament or bone marrow oedema and cysts of the greater tuberosity) can often be seen.

Non-surgical management

Primary treatment of impingement syndrome should be conservative after having ruled out any structural damage to the shoulder joint following assessment through clinical examination and imaging. Several publications recommend at least 3 months of conservative treatment, although there is no existing evidence for the optimal duration, frequency or type of exercise therapy [11]. Notably, and to the best of the authorsʼ knowledge, there is no data concerning outcome after conservative treatment comparing SAPS/SIS and MOI/MNOI. It therefore remains unclear, and should be decided on a case-by-case basis, which duration, intensity and type of conservative management should be recommended for each patient.

There are various treatment options for conservative therapy. In 2017, Steuri et al. published a systematic review in which they analysed conservative treatment methods [34]. The study group described a better outcome after each conservative treatment when compared to placebo or sham treatment. Haahr et al. found that the outcome after subacromial decompression is comparable to physiotherapy in a comparison study with 1‑year follow-up [13].

Several RCTs and reviews have shown that exercise therapy can reduce pain and increase range of motion in a short-term follow-up for up to 6 months [12, 24, 34]. Nevertheless, it is difficult to interpret the effectiveness of exercise and manual therapy in these studies, as the therapy protocol for the patients to be included remains unclear. Furthermore, inclusion criteria do not differentiate between the pathologies of SAPS/SIS or MOI/MNOI. It can be concluded that there are short-term positive effects for primary treatment with exercise therapy, anti-inflammatory drugs and steroid injections in patients with general subacromial pain.

Surgical management

Operative treatment can be considered in patients with persistent subacromial pain that has not responded to adequate conservative therapy.

Subacromial decompression can be performed in an open or arthroscopic approach, and arthroscopic subacromial decompression has become the standard surgical treatment option due to the fact that it is minimally invasive and has a lower risk of infection and a lower level of postoperative pain. Figures 2 and 3 show intraoperative images of arthroscopic subacromial decompression and findings in patients with MOI/MNOI.

Of note, bursectomy seems to be a critical element in the surgical procedure. Henkus et al. compared the surgical procedure of bursectomy alone versus subacromial decompression and bursectomy in a prospective study in 2009. They followed 57 patients for more than 2.5 years. Inclusion and exclusion criteria can be seen in Table 1. In both groups there was a statistically significant increase in Constant score and simple shoulder test after a median follow-up of 2.5 years as well as in a second study after 9–14 years. There was no significant difference in outcome after bursectomy alone compared to subacromial decompression and bursectomy [15, 21]. Analysis of the subgroups revealed a worse outcome in Constant score for patients with a sloped or hooked acromion. These results support the view that even bursectomy alone benefits patients. In the presence of a mechanical reason for impingement (as in MOI/MNOI), bursectomy alone is unlikely to be adequate, and subacromial decompression is therefore recommended.

More numerous studies show consistently good and satisfying results in the long-term follow-up [9, 20, 25]. In 2016, Lerch et al. published a review on long-term findings after subacromial decompression [23]. They included studies with a follow-up from 2–20 years after subacromial decompression in patients with isolated impingement or additional partial ruptures of the rotator cuff. All cited publications were of a level of evidence of III or IV and reported good or very good results in the long-term follow-up.

Surgical vs. non-surgical treatment

The number of high-level randomized controlled trials comparing surgical or non-surgical treatments in subacromial impingement is low. One of the most recent systematic reviews is from Saltychev et al. in 2015, in which seven randomized controlled trials were identified and analysed [32]. In four of the seven included studies, surgical management was superior to non-surgical therapy, three studies did not show any difference in outcome between the surgical and non-surgical group [3, 4, 19, 30, 31] and two of the studies showed that both surgical and non-surgical treatment were superior to waiting and neglecting. To create a study with a higher level of evidence, Beard et al. published a multicentre randomized trial in 2018 entitled “Can shoulder arthroscopy work” (CSAW Trial) [2]. Patients were randomized to a verum group (n = 106), placebo group (n = 103) and control group without therapy (n = 232). Patients included in the verum group received standardized treatment with subacromial decompression, and the placebo treatment included joint and subacromial lavage. Patients with SAPS were included in the study with the diagnosis being made based on a physician’s decision. More detailed selection criteria such as detailed history, documentation of clinical tests, development of symptoms after corticoid injection and radiological signs of subacromial impingement were not mentioned as inclusion criteria. Included patients showed various and different diagnoses including partial rotator cuff tears. The results of the CSAW Trial did not show a significant advantage for subacromial decompression compared to joint lavage in the short-term follow-up. Both interventions showed an advantage compared to the control group without treatment. The results were recorded 6 months after randomization. As various patients waited several months after randomization before going into surgery, the follow-up result of these patients was as little as 2 months after surgery. Due to these short-term results and unspecific inclusion criteria, this trial offers limited help with answering the question of the benefit of subacromial decompression in the different types of impingement. It is possible that a therapeutic benefit may have been achieved by the mechanical irritation of the bursal tissue in patients that received placebo lavage.

Also in 2018, Paavola et al. compared the procedure of subacromial decompression to a control intervention and a conservative treatment path (Finnish Subacromial Impingement Arthroscopy Controlled Trial, FIMPACT) [29]. They included 210 patients having suffered subacromial pain for more than 3 months. All patients had undergone conservative treatment before. Radiological parameters were considered while ruling patients in. There was a two-to-one randomization for the surgery and conservative groups. Patients included in the surgery group were scheduled for diagnostic arthroscopy during which the rotator cuff was examined from the articular and subacromial side. If the rotator cuff was intact, the patient was then randomized again into the subacromial decompression group, in which they received surgery up to standard surgery protocol, or diagnostic arthroscopy group, in which case nothing more was done. All patients visited at 6, 12 and 24 months postoperatively. The results of this study did not show a statistically significant difference in outcome when comparing the two operation methods concerning pain during activity and at rest (visual analogue scale, VAS). There were statistically significant better results in Constant score and pain (VAS) in the surgery group compared to conservative treatment, but these differences were not relevant in day-to-day life. As in the CSAW trial, FIMPACT did not document intraoperative signs of MOI. The FIMPACT Trial also did not describe or study the exact pathology responsible for the subacromial impingement.

An important factor of the CSAW and FIMPACT trials is the definition of the placebo intervention. Diagnostic arthroscopy implies lavage and at least partial bursectomy in the subacromial space. As mentioned above, this procedure can have as equally good results as subacromial decompression and cannot be called a sham surgery [8]. It could instead be described as an active control intervention. The CSAW and FIMPACT trials therefore underline the therapeutic effects of surgical intervention concerning subacromial bursectomy, and CSAW provides evidence for a surgical benefit compared with conservative treatment.

Farfaras et al. examined 10-year follow-up after open acromioplasty, arthroscopic decompression and physiotherapy alone in subacromial impingement in a prospective randomized trial in 2018 [10]. The study group included 87 patients that had completed 6‑month conservative treatment without any benefit and were tested positive for Neer and Hawkins tests in clinical examination. At the 10-year follow-up there was a statistically significant increase in Constant score in both surgery groups, but no increase in the exercise group. Concerning the development of shoulder arthropathy or rotator cuff tears, there was no difference in occurrence in all three groups. These long-term results over 10 years show that subacromial decompression is more beneficial than exercise therapy alone in selected patients. Radiological exams were not included in the evaluation.

A Finnish study group recently published a Cochrane-review and a systematic review and meta-analysis on surgery for subacromial decompression [17, 22]. They also base their recommendation on the studies mentioned above; therefore, these reviews unfortunately only reproduce the aforementioned studies and resulting critique. Table 4 summarizes all inclusion criteria of the cited studies.

Conclusion

The outcome for patients treated with conservative therapy or subacromial decompression who explicitly suffered from MOI or MNOI has not yet been studied. Publications to date include various and mixed pathologies. None of the existing studies specifically differentiate between the explained types of impingement SIS/SAPS and MOI/MNOI and this significantly compromises the transferability of these recommendations, making decisions difficult when considering individual cases. Differential, evidence-based inclusion criteria for diagnosing MOI/MNOI are not used in any of the studies completed to date. Therefore, when reading and interpreting studies, it should always be kept in mind that any published recommendations relating to diagnostic tests and indications for treatment have been based on a heterogeneous cohort of patients, which may not be relevant in all or most cases. It seems likely that especially patients with a mechanical and therefore structural narrowing of the subacromial space can profit more from surgical management than patients with unspecific subacromial pain. In addition to that, it is of major importance to preserve the supraspinatus tendon and to therefore reduce the risk of rupture by figuring out tendons at risk caused by MOI and introducing those patients to surgery.

References

Balke M, Schmidt C, Dedy N et al (2013) Correlation of acromial morphology with impingement syndrome and rotator cuff tears. Acta Orthop 84:178–183

Beard DJ, Rees JL, Cook JA et al (2018) Arthroscopic subacromial decompression for subacromial shoulder pain (CSAW): a multicentre, pragmatic, parallel group, placebo-controlled, three-group, randomised surgical trial. Lancet 391:329–338

Brox JI, Gjengedal E, Uppheim G et al (1999) Arthroscopic surgery versus supervised exercises in patients with rotator cuff disease (stage II impingement syndrome): a prospective, randomized, controlled study in 125 patients with a 2 1/2-year follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 8:102–111

Brox JI, Staff PH, Ljunggren AE et al (1993) Arthroscopic surgery compared with supervised exercises in patients with rotator cuff disease (stage II impingement syndrome). BMJ 307:899–903

Calis HT, Berberoglu N, Calis M (2011) Are ultrasound, laser and exercise superior to each other in the treatment of subacromial impingement syndrome? A randomized clinical trial. Eur J Phys Rehabil Med 47:375–380

Deutsche Vereinigung für Schulter- und Ellenbogenchirurgie (2017) Bildgebung in der Schulter- und Ellenbogenchirurgie. Obere Extrem 12:1–84. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11678-017-0401-9

Diercks R, Bron C, Dorrestijn O et al (2014) Guideline for diagnosis and treatment of subacromial pain syndrome: a multidisciplinary review by the Dutch Orthopaedic Association. Acta Orthop 85:314–322

Donigan JA, Wolf BR (2011) Arthroscopic subacromial decompression: acromioplasty versus bursectomy alone—does it really matter? A systematic review. Iowa Orthop J 31:121–126

Ellman H (1987) Arthroscopic subacromial decompression: analysis of one- to three-year results. Arthroscopy 3:173–181

Farfaras S, Sernert N, Rostgard Christensen L et al (2018) Subacromial decompression yields a better clinical outcome than therapy alone: a prospective randomized study of patients with a minimum 10-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 46:1397–1407

Garving C, Jakob S, Bauer I et al (2017) Impingement syndrome of the shoulder. Dtsch Arztebl Int 114:765–776

Gebremariam L, Hay EM, Van Der Sande R et al (2014) Subacromial impingement syndrome—effectiveness of physiotherapy and manual therapy. Br J Sports Med 48:1202–1208

Haahr JP, Ostergaard S, Dalsgaard J et al (2005) Exercises versus arthroscopic decompression in patients with subacromial impingement: a randomised, controlled study in 90 cases with a one year follow up. Ann Rheum Dis 64:760–764

Habermeyer P, Lichtenberg S, Magosch P (eds) (2010) Schulterchirurgie. Urban & Fischer/Elsevier, München

Henkus HE, De Witte PB, Nelissen RG et al (2009) Bursectomy compared with acromioplasty in the management of subacromial impingement syndrome: a prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 91:504–510

Kappe T, Knappe K, Elsharkawi M et al (2015) Predictive value of preoperative clinical examination for subacromial decompression in impingement syndrome. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23:443–448

Karjalainen TV, Jain NB, Page CM et al (2019) Subacromial decompression surgery for rotator cuff disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 1:CD5619

Kessel L, Watson M (1977) The painful arc syndrome. Clinical classification as a guide to management. J Bone Joint Surg Br 59:166–172

Ketola S, Lehtinen J, Arnala I et al (2009) Does arthroscopic acromioplasty provide any additional value in the treatment of shoulder impingement syndrome?: A two-year randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br 91:1326–1334

Klintberg IH, Svantesson U, Karlsson J (2010) Long-term patient satisfaction and functional outcome 8–11 years after subacromial decompression. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 18:394–403

Kolk A, Thomassen BJW, Hund H et al (2017) Does acromioplasty result in favorable clinical and radiologic outcomes in the management of chronic subacromial pain syndrome? A double-blinded randomized clinical trial with 9 to 14 years’ follow-up. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 26:1407–1415

Lahdeoja T, Karjalainen T, Jokihaara J et al (2019) Subacromial decompression surgery for adults with shoulder pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med 54(11):665–673

Lerch S, Elki S, Jaeger M et al (2016) Arthroscopic subacromial decompression. Oper Orthop Traumatol 28:373–391

Lombardi I Jr, Magri AG, Fleury AM et al (2008) Progressive resistance training in patients with shoulder impingement syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 59:615–622

Lunsjo K, Bengtsson M, Nordqvist A et al (2011) Patients with shoulder impingement remain satisfied 6 years after arthroscopic subacromial decompression: a prospective study of 46 patients. Acta Orthop 82:711–713

Magaji SA, Singh HP, Pandey RK (2012) Arthroscopic subacromial decompression is effective in selected patients with shoulder impingement syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Br 94:1086–1089

Neer CS 2nd (2005) Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder. 1972. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87:1399

Neer CS 2nd, Welsh RP (1977) The shoulder in sports. Orthop Clin North Am 8:583–591

Paavola M, Malmivaara A, Taimela S et al (2018) Subacromial decompression versus diagnostic arthroscopy for shoulder impingement: randomised, placebo surgery controlled clinical trial. BMJ 362:k2860

Peters G, Kohn D (1997) Mid-term clinical results after surgical versus conservative treatment of subacromial impingement syndrome. Unfallchirurg 100:623–629

Rahme H, Solem-Bertoft E, Westerberg CE et al (1998) The subacromial impingement syndrome. A study of results of treatment with special emphasis on predictive factors and pain-generating mechanisms. Scand J Rehabil Med 30:253–262

Saltychev M, Aarimaa V, Virolainen P et al (2015) Conservative treatment or surgery for shoulder impingement: systematic review and meta-analysis. Disabil Rehabil 37:1–8

Singh HP, Mehta SS, Pandey R (2014) A preoperative scoring system to select patients for arthroscopic subacromial decompression. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 23:1251–1256

Steuri R, Sattelmayer M, Elsig S et al (2017) Effectiveness of conservative interventions including exercise, manual therapy and medical management in adults with shoulder impingement: a systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs. Br J Sports Med 51:1340–1347

Funding

Open access funding provided by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S.M. Hünnebeck, M. Balke, R. Müller-Rath and M. Scheibel declare that they have no competing interests.

For this article no studies with human participants or animals were performed by any of the authors. All studies performed were in accordance with the ethical standards indicated in each case.

Rights and permissions

Open Access. This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hünnebeck, S.M., Balke, M., Müller-Rath, R. et al. Evidence-based recommendations for the treatment of mechanical outlet impingement. Obere Extremität 15, 217–227 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11678-020-00579-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11678-020-00579-9