Abstract

The biodiversity of natural or semi-natural native, old oak woodlands have high conservation importance, especially in landscapes of monocultural forest plantations and arable fields. With a wider variety of microhabitats and foraging sources, such old oak forests can provide essential habitat for native forest bird communities. We conducted a study using bird point counts to compare the forest bird communities of old pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) remnants with native and non-native plantations in central Hungary in a landscape of mostly arable fields, settlements, and monocultural plantations. Avian surveys were carried out in old oak forest remnants, middle-aged oak, white poplar (Populus alba), hybrid poplar (Populus × euramericana), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), and pine (Pinus spp.) plantations. Fieldwork has been carried out in nine study sites, where all six habitat types were represented (with a few exceptions), to determine total abundance, species richness, Shannon–Wiener diversity, species evenness, dominant and indicator species, and guild abundances. We found that old oak forest remnants were the most diverse habitats among the studied forest types, while hybrid poplar and pine plantations exhibited the lowest avian biodiversity. The avian guilds most sensitive to the loss of old oak forest remnants were ground foragers, bark foragers, cavity-nesters, residents, and Mediterranean migratory birds. Native habitats were more diverse than non-native plantations. Our results suggest that it is important to conserve all remaining high biodiversity old oak stands and to avoid clear-cutting of monocultural plantations in favour of practices such as mixed-species plantations, longer rotation lengths, or retention forestry.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The vast majority of natural forests are now altered worldwide by urbanization, agriculture, and various kinds of forest management practices. Less than 1% of European forests remain natural. Natural forests have heterogeneous tree species and age composition, with multi-layered habitat structure and diverse microhabitats. Such elements make natural forests optimal habitats for forest-dwelling species. Among the numerous existing forest management practices, monocultural commercial tree plantations are considered to result in the poorest habitats for forest communities (Paillet et al. 2010). Species richness is higher in natural forests than in commercial plantations and both species richness and abundance are significantly higher in complex than in structurally simple plantations (Nájera and Simonetti 2010). Unfortunately, monocultural managed forest plantations are widespread and expanding worldwide, with commercial plantations representing > 7% of global forest cover (Horák et al. 2019). Plantations attempt to maximize wood production (either timber or pulp) of particular tree species (Carnus et al. 2006; Paillet et al. 2010). Globally, at least one-quarter of commercial plantations now consist of non-native species. Non-native monocultural plantations have a devastating impact on native biodiversity and are frequently considered ‘green deserts’ (Bremer and Farley 2010; Horák et al. 2019). Changing natural or seminatural forests to plantations lowers avian biodiversity, species richness and overall abundance worldwide while transforming the composition of forest bird communities to include fewer forest specialists, more habitat generalists, and more species that prefer open habitats (Hansen et al. 1991; Farwig et al. 2008; Sheldon et al. 2010; Sweeney et al. 2010a).

Managed forests of Europe have lower biodiversity and species richness in terms of bryophytes, lichens, fungi, saproxylic beetles, and carabids (Paillet et al. 2010). Among forestry management practices, clearcutting systems of commercial plantations are the most disadvantageous for biodiversity compared to thinning or selective cutting. Short-rotation clear-cutting systems of native plantations, however, can foster higher diversity comparing to arable fields (Torras et al. 2012; Chaudhary et al. 2016).

The transitional biomes of forest steppes are considered to be among the most diverse ecosystems outside the tropics and have high conservation importance (Hoekstra et al. 2005; Erdős et al. 2018). Forest steppes are present in both North and South America, while the largest areas of such habitats are found in Eurasia. Eurasian forest steppes extend from sub-Mediterranean to ultracontinental or monsoon climate zones, from Southeast Europe to the near the Pacific coast. These mosaic habitats consist of forests, shrublands, and grasslands, while their dominant tree species can be either deciduous or coniferous. These habitats can be economically beneficial to local communities as pastures. Forest steppes are, however, among the most threatened ecosystems because of habitat loss, fragmentation, and poor management (Hoekstra et al. 2005; Erdős et al. 2018; Rédei et al. 2020).

Oak (Quercus sp.) forests of high biodiversity throughout Eurasia and the Americas provide a wide variety of ecosystem services from high-value timber harvesting to recreation. The worldwide task is to keep a balance among ecosystem services to sustain biodiversity while harvesting timber for profit (Löf et al. 2016). Natural old oak forests have diverse habitat structure and can harbour a wide variety of forest specialist bird species that includes woodpeckers, a group that needs diverse microhabitats such as coarse woody debris, snags, decaying and dead trees. Such habitats also have various other cavity-nesting species such as tits (Paridae) and flycatchers (Ficedulidae and Muscicapidae) (Proença et al. 2010; Robles et al. 2011; Domokos and Cristea 2014; Olano et al. 2015). The diverse canopy and shrub layers also provide nesting and foraging habitat for foliage insectivore species like Eurasian blackcap (Sylvia atricapilla) and Eurasian golden oriole (Oriolus oriolus). The nutrient-rich leaf litter provides foraging habitat for ground insectivores, like Hoopoe (Upupa epops) or song thrush (Turdus philomelos). Seed crops of such diverse habitats are essential foraging sources for granivores such as hawfinch (Coccothraustes coccothraustes) or European greenfinch (Chloris chloris) (Domokos and Cristea 2014; Czeszczewik et al. 2015; Wesołowski et al. 2015).

The Pannonian biogeographical region encompasses all of Hungary and extends outward to include 3% of the total EU land area (EC 2021). It is recognised as a site of EU regional importance for biodiversity conservation, supporting some 70 species of birds that are listed for strict protection in the EU Birds Directive (EEC 2009). Forest steppe vegetation of the Pannonian lowlands is the westernmost extended exclave of the Eurasian forest-steppes (Erdős et al. 2018). The pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) dominated forest steppes are critically endangered in the Pannonian sand region (Rédei et al. 2020). Due the climatic and edaphic conditions, European zonal forests reach here the dry border of their tolerance. Spontaneous regeneration of the dominant pedunculate oak is limited. Due to aridification and the lowering of the groundwater table, oaks have not regenerated sufficiently in the region in recent decades, which is why non-native species were planted more in the plantations (Rédei et al. 2020). On the other hand, there is a large growth in nationwide forestation projects that often include non-native plantations. Ironically, the use of non-native species continues to be funded by the government. This way, extent of the seminatural forest stands reduced heavily in the region. The remaining old oak forest remnants have exceptionally high biodiversity and conservation importance (Bíró et al. 2008), with a land coverage of approximately 6,000 ha in Hungary (Bölöni et al. 2008), currently considered an endangered habitat (Borhidi 1999; Rédei et al. 2020).

On the Great Hungarian Plain, most of the existing forests are even-aged, commercial plantations, including native stands, like pedunculate oak and the mixture of white poplar (Populus alba) and grey poplar (P. × canescens) (hereafter ‘native poplar’ stands), or non-native ones like hybrid poplar (P. × euramericana), black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia), and pine (Pinus spp.) plantations. Each commercial species has a relatively short rotation time.

In Hungary, after the human activities of the past 200 years, forest-steppes have undergone major changes, and only 251,000 ha (6.8%) of the total of 3,700,000 ha have survived and only 5.5% of the present stands can be considered natural (Molnár et al. 2012). Currently, all components of forest steppes in Hungary consist of heavily fragmented mosaics with croplands and commercial, monocultural plantations of native and non-native tree species.

Despite their conservation importance, few studies have focused on the significance of natural, seminatural, unmanaged or less-managed oak habitats for forest birds. Those that have been conducted have been primarily focused on the difference between the avifauna of native and non-native stands (Magura et al. 2008), or the non-native invasion of native stands (Laiolo et al. 2003; Hanzelka and Reif 2015).

Our study focused on the avifauna of a forest matrix of six forest types (old oak remnants, oak plantations, native poplar, hybrid poplar, black locust, and pine), seeking out both the effects of forest type and the effects of short-rotation clearcutting systems on forest bird communities, as bird species are considered to be indicators of habitat quality (Coote et al. 2013; Gao et al. 2015; Duguid et al. 2016). Our goal was to address the following questions:

-

Which bird species groups are the most sensitive to current forestry practices?

-

Can native plantations be considered better habitat for forest bird communities compared with non-native plantations?

-

Can forest plantations conserve forest bird diversity of natural old oak remnants, under present landscape management practices?

We compared the six habitat types in terms of species richness, Shannon–Wiener diversity, species evenness, total abundance and abundance of foraging, nesting, and migratory guilds. We also identified the dominant and specialist species and estimated the importance of each bird species of the studied forest stands.

Materials and methods

Study area

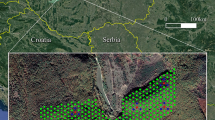

Nine study sites were chosen, in the vicinity of the following settlements: Csévharaszt, Hetényegyháza, Kunbaracs, Kunpeszér, Nagykőrös, Nyárlőrinc, and Pusztavacs, Szabadszállás and Tatárszentgyörgy (Fig. 1), where each or most of the six considered forest types were present. Only stands with an area > 3 ha were selected for the study. The number of study sites, thus the sample size, was limited by the number of old oak forest remnants that large enough: all old oak stands that met the requirement were sampled.

The maximum age of planted stands was determined by the rotation length of each plantation type. The minimum age was established to include only the oldest stands at each site. Six habitat types were represented at each site:

-

(1)

Old oak forests ≥ 80 years old natural or semi-natural, closed stands, consisted mainly of pedunculate oak and mixed with native tree species such as white and black poplar, Tatar maple (Acer tataricum) and very rarely European hornbeam (Carpinus betulus). These forests had an uneven-aged structure with a high density of standing and fallen deadwood. The diameter at breast height (dbh) of the thickest trees was about 120 cm. The tree cover of old oak forest remnants was consistent in time (maintained mainly by the management practice of coppicing), although these stands became more and more fragmented over time. These stands are ancient forests (with the permanent historical presence of forests), according to Buchwald (2005) they belong to the recently (n4) or long (n5) untouched forests with many old characteristics as the occurrence of e.g. large logs and snags, veteran living and partly senescent trees. The humus-rich soil on the sandy substrate of such forests was undisturbed but contributed to aridification, a problem that is typically addressed by clear-cutting, followed by full soil preparations and the planting of native or non-native monocultures.

-

(2)

Middle-aged managed oak plantations were 50–80 years old, even-aged, closed stands that consisted mainly of pedunculate oak. The DBH of trees was 10–60 cm.

-

(3)

Native poplar stands were 30–60 years old, even-aged, closed monocultural plantations, with a DBH of 10–60 cm.

-

(4)

Hybrid poplar stands were 20–25 years old, even-aged, closed monocultural plantations. The DBH of trees in the canopy was 10–40 cm.

-

(5)

Black locust stands were 20–40 years old, even-aged, closed monocultural plantations with a DBH of 10–40 cm.

-

(6)

Pine stands were 30–50 years old, even-aged, closed plantations of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris), black pine (P. nigra), or both with a DBH of 10–40 cm.

As the age of plantations was close to their rotation length, a considerable amount of standing and fallen deadwood was found in the stands depending on the intensity of management.

The shrub layer of native habitat types consisted mainly of species with fleshy fruits dispersed via endozoochory, including common hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna), elder (Sambucus nigra), common dogwood (Cornus sanguinea), European spindle (Euonimus europaeus), European wild pear (Pyrus piraster), common buckthorn (Rhamnus cathartica), European barberry (Berberis vulgaris), European dewberry (Rubus caesius), and the alien black cherry (Prunus serotina). Above these shrubs, non-endozoochorous species were present, such as common hazel (Corylus avellana). The shrub layer was almost absent from hybrid poplar, black locust, and pine plantations, partly because of the cutting of shrubs, but in some cases, hawthorn, black cherry, and European dewberry established via endozoochory.

Data collection

Two-visit point counts were made. Point count stations were sampled at each of our nine study sites. All of the studied forest types were represented in point count stations at all sites with three exceptions. In the site of Hetényegyháza, there was no hybrid poplar plantation suitable for the criteria; in the site of Nyárlőrinc, there was no pine plantation that met the criteria. We did not make counts in the appointed black locust plantation of Tatárszentgyörgy, because it was smaller and closer to the other studied stands than to meet with the requirements of our protocol). Point count stations were made at least 250 m apart from each other and at least 50 m from the forest edge. Depending on the extension of the particular forest unit, there were cases where we appointed more than one point count stations (up to four, to avoid oversampling). We maximized the number of point count stations in each study sites in ten so that we assured that survey can be logistically made from one hour after sunrise to late morning (until the temperature reached 25 °C). In our study, we appointed altogether 80 point count stations. Visits were made from April to June 2018. Due to forestry activity and other logistical considerations, ten point count stations could only be visited once. After a three minute waiting period, made to mitigate disturbance caused by the approaching observer, all birds seen or heard during the next ten minutes within a 50 m radius were counted. Each visit was made in opposite directions at each site to avoid any bias associated with interrupting the daily activity of birds. Counts were carried out during days without any heavy rain or wind.

Analyses

For points visited twice, the higher observed abundance of each species was used in the analysis. Total abundance, species richness, Shannon–Wiener diversity, and species evenness were calculated for each point.

Species were assigned to guilds according to their foraging and nesting preferences and migratory strategies. Total abundance was calculated for each foraging, nesting, and migratory guild. Guilds were assigned based on earlier studies (Czeszczewik et al. 2015; Domokos and Domokos 2016), the database of www.birdlife.org and the database of the BirdLife Hungary (www.mme.hu). We assigned species in the following foraging guilds: foraging outside the forest (such as black stork Ciconia nigra), predator (foraging on vertebrates), herbivore, ground insectivore, bark insectivore, foliage insectivore, airborne insectivore, scavenger, and omnivore. Nesting guilds were classified as ground-nester, midstory-nester, canopy-nester, cavity-nester, and nest parasite. Migratory guilds were classified after where the species spend the winter as resident, Mediterranean migratory, sub-Saharan migratory species.

For comparison of forest types, we fitted generalized linear mixed models (hereafter GLMM) using habitat type as fixed and study site as a random factor (Zuur et al. 2009). For total abundance, species richness, and guild abundances, Poisson or negative binomial distributions were used, based on the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC, Akaike 1973). For Shannon–Wiener diversity and species evenness, gamma distribution was fitted. Overall differences between habitat types were tested using likelihood ratio tests. If there were overall significant differences among types, Tukey post hoc tests of multiple comparisons were made.

The relative frequency was calculated for each species at each point. A species was considered to be dominant if its relative frequency was greater than 0.05 (Fulco and Tellini Florenzo 2008). We calculated point biserial correlation (De Cáceres and Legendre 2009) as an indicator species value for each species, to determine which species were more important in the evaluation of habitat quality (Dufrêne and Legendre 1997; Domokos and Domokos 2016). A particular species can be an indicator of more than one habitat type; therefore multi-level analysis was applied (De Cáceres et al. 2010).

We conducted the analyses in R version 3.6.3 (R Core Team 2020) using glmmTMB (version 1.0.1.9000; Brooks et al. 2017), multcomp (version 1.4-10, Hothorn et al. 2008), emmeans (version 1.4.7, Lenth 2020) and indicspecies (version 1.7.6) packages.

Results

A total of 41 bird species, represented by 1194 birds were recorded in the overall study: 33 species in old oak forest remnants, 29 in managed oak, 24 in native poplar, 20 in hybrid poplar, 23 in black locust, and 25 in pine.

On the community level, GLMM was fit to negative binomial distribution in total abundance, to Poisson distribution in species richness and to gamma distribution in Shannon–Wiener diversity and species evenness. We found overall significant differences between habitat types in total abundance (χ2 = 60.966, df = 5, P < 0.0001, species richness (χ2 = 44.522, df = 5, P < 0.0001), Shannon–Wiener diversity (χ2 = 42.205, df = 5, P < 0.0001) and species evenness (χ2 = 51.437, df = 5, P < 0.0001).

Old oak forest yielded significantly higher bird abundance than did all other forest types. Managed oak yielded significantly higher abundance than did hybrid poplar (Fig. 2a). Old oak forests were significantly higher in species richness than native poplar, hybrid poplar, black locust, and pine stands. Managed oak forests had significantly higher species richness than hybrid poplar stands as well (Fig. 2b). In the case of Shannon–Wiener diversity, old oak forests had significantly higher values relative to all other forest types, excluding managed oak stands (Fig. 2c). Old oak forests showed significantly higher species evenness comparing to other habitat types while managed oak forests were significantly higher in species evenness than hybrid poplar plantations (Fig. 2d).

On the guild level, GLMM was fit to Poisson distribution for most guild abundance variables, except for the cavity-nesting birds and those that are foraging outside the forest. We found significant overall differences between habitat types for the abundances of the following guilds: ground insectivore (χ2 = 32.286, df = 5, P < 0.0001), bark insectivore (χ2 = 62.081, df = 5, P < 0.0001), foliage insectivore (χ2 = 14.1, df = 5, P < 0.05), midstorey-nester (χ2 = 15.098, df = 5, P < 0.05), cavity-nester (χ2 = 52.473, df = 5, P < 0.0001), resident (χ2 = 86.354, df = 5, P < 0.0001) and Mediterranean migrator (χ2 = 24.761, df = 5, P < 0.001).

The posthoc test revealed that, in terms of herbivores, the studied forest types were not significantly different from each other (Fig. 2e). There were significantly more ground insectivores in old oak forests compared to all other types, except for managed oak forests. The other types did not differ significantly from each other (Fig. 2f). There were also significantly more bark foragers in old oak forests compared to other types except for managed oak forests. Managed oak had a significantly higher abundance of bark foragers than pine and hybrid poplar stands had. Bark foragers were significantly more abundant in native poplar type than in hybrid poplar type. Black locust stands had significantly more bark foragers than hybrid poplar stands (Fig. 2g). Foliage insectivores were significantly more abundant in old oak forests than in managed oak and black locust stands (Fig. 2h).

Midstory-nesters were significantly more abundant in old oaks than in hybrid poplar plantations (Fig. 2i). Old oak forest remnants had significantly more cavity-nesters than all the other types except for managed oak stands. Managed oak stands also had significantly more cavity-nesters than hybrid poplar plantations (Fig. 2j).

Significantly more resident birds were recorded within the old oak forests than all the other habitats. Managed oak stands also had significantly more residents than hybrid poplar stands (Fig. 2k). Old oak forests had significantly more Mediterranean migratory birds than hybrid poplar and pine stands (Fig. 2l).

We found nine dominant species in old oak, managed oak, and hybrid poplar stands, eight in native poplar and black locust stands, and ten in pine stands. The most frequent species was the great tit (Parus major) in every forest type except pine stands, where common chaffinch was the most frequent species. Blue tit (Cyanistes caeruleus), chiffchaff (Phylloscopus collybita), Eurasian blackcap, Eurasian nuthatch (Sitta europaea), European robin (Erithacus rubecula), common starling (Sturnus vulgaris) and common chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs) were dominant in almost every type (Table 1).

Six species preferred old oak forests: short-toed treecreeper (Certhia brachydactyla; r = 0.469, P < 0.01), blue tit (r = 0.459, P < 0.01), song thrush (r = 0.428, P < 0.01), Eurasian jay (Garrulus glandarius; r = 0.404, P < 0.01), stock dove (Columba oenas; r = 0.365, P < 0.05), and common blackbird (Turdus merula; r = 0.347, P < 0.05). European robin (r = 0.536, P < 0.01) and middle spotted woodpecker (Leiopicus medius; r = 0.488; P < 0.01) preferred oak forests, irrespective of management status. Coal tit (Periparus ater; r = 0.580, P < 0.01) and common chaffinch (r = 0.336, P < 0.05) preferred pine forests, while Eurasian nuthatch (r = 0.554, P < 0.01) preferred deciduous types. Above all, black woodpecker (Dryocopus martius; r = 0.352, P < 0.05) preferred old oak and native poplar stands and tree pipit (Anthus trivialis; r = 0.384, P < 0.05) preferred black locust and poplar (both native and hybrid) forests.

Discussion

We found that old oak forest remnants harboured the highest bird diversity and species evenness of forest types examined. In this fragmented forest landscape, these old forests had the most diverse avifauna with the highest species richness and total abundance. Dominant species were common chaffinch, European robin, Eurasian blackcap, common starling, and great tit, as also reported by Wesołowski et al. (2015) who studied the avifauna of oak-lime-hornbeam (Tilio-Carpinetum) stands at Białowieża National Park in Eastern Poland. Due to the nutrient-rich, diverse, native leaf litter, old oak remnants had high importance for ground insectivore species, such as song thrush and common blackbirds. Due to its age, this type of forest had more decaying and dead trees with diverse microhabitats than the other types had, thus old remnant oak forests were the most important for bark insectivores like short-toed treecreeper, Eurasian nuthatch, woodpecker species (Picidae, e.g., middle spotted and black woodpecker) and other cavity-nesters (e.g., blue tit and stock dove). For cavity-nesting species, it is important to conserve such stands because hardwood oak trees need more time for cavities to be formed compared to softwood tree species (Quine et al. 2007; Ranius et al. 2009).

As most non-migratory species are among the above-mentioned guilds, old oak stands in our study had high conservation value for this guild. Old oak stands were more abundant in terms of canopy insectivores than managed oak stands, as old oak forests have more diverse, multi-level canopy structure, compared to even-aged managed oak stands with simpler canopy structure (Ceia and Ramos 2016). With the conservation of old oak stands, managers could promote a diverse community of insectivorous bird species, potentially source populations of species that have important roles controlling pests in a landscape of forest plantations (Ceia and Ramos 2016). Oak forests that are older than 80 years have diverse forest structure and are more beneficial habitats compared to younger stands with less diverse structure (Domokos and Cristea 2014).

Monocultural oak plantations can support comparable bird communities to old oak remnants, although those plantations are poorer in microhabitats than natural oak woods. Nonetheless, these plantations can provide better conditions for forest birds such as European robin and middle spotted woodpecker than non-native plantations (Graham et al. 2014). On the other hand, commercial oak plantations can only conserve a fraction of the avifauna of the structurally more diverse old oak forests under the present clear-cutting practices (Felton et al. 2016). Old oak stands can provide structurally more diverse habitats and more potential tree cavities for secondary cavity nesters (Robles et al. 2011).

Foliage insectivores were present in lower abundances in oak plantations compared to old oak stands, as these plantations have a more open midstory layer. Graham et al. (2014) also found such results in a similar study in Ireland, made in semi-natural and monocultural oak plantations. More bark-foraging species were found in ‘native poplar’ plantations comparing to hybrid poplar stands. The Eurasian aspen (Populus tremula) (which is closely related to white and grey poplar), through its softwood and diverse bark structure, can provide crucial microhabitats for forest birds, especially bark-foraging species, such as woodpeckers (Hansson 1992; Walankiewicz and Czeszczewik 2005; Kosiński and Kempa 2007; Hebda et al. 2017). Black woodpeckers were only found in ‘native poplar’ plantations in addition to old oak remnants. Consequently, dominant tree species and structure together determine the high richness of bird communities of the seminatural oak stands.

Hybrid poplars are hybrids of the native black poplar (Populus nigra) and numerous North American poplar species and have been planted throughout Europe (Camprodon et al. 2015). Hybrid poplar plantations may have a role as ‘green corridor’ for forest birds, but stands that are near the end of their rotation time could provide nesting habitat in the short term for forest specialists, such as lesser spotted woodpeckers (Dryobates minor) (Martín-García et al. 2013; Camprodon et al. 2015). In our study, hybrid poplar plantations proved to be poor habitat for birds, with less structured microhabitats, because of the regular midstory encroachment used to increase timber production. As found for other non-native plantations, some species (e.g. Eurasian golden oriole, tree pipit) preferred more open habitats. Generalist forest species (e.g. common chaffinch and great tit) were also found in non-native stands. Martín-García et al. (2013) showed similar results in a study of poplar plantations and riparian forests in Spain. They suggested that managers should not control the understory of poplar plantations, so this habitat could harbour more forest specialist species. More appropriate rotation lengths can also make poplar plantations better habitats to meet conservation goals by providing more decaying and dead trees that enrich the diversity of microhabitats (Riffell et al. 2011; Camprodon et al. 2015; Turkalj 2017).

Black locust stands exhibited both lower bird diversity and species richness, and mostly forest habitat generalist species were present such as great tits, common chaffinches, European robins, or Eurasian blackcaps. Such stands were also used by species that prefer more open forest structure like spotted flycatchers (Muscicapa striata) or common starlings (Hanzelka and Reif 2015; Kroftová and Reif 2017). As the black locust stands were close to the end of their rotation time, with a considerable amount of standing deadwood that provided tree holes, it is also understandable that even less common species that favour more open forests with standing deadwood, such as collared flycatchers (Ficedula albicollis) were also present (Hanzelka and Reif 2015). Middle spotted woodpecker, which also requires forest habitats with plenty of decaying and dead trees (Domínguez et al. 2017) was also present in two black locust stands of our study, although, in contrast to collared flycatchers, middle spotted woodpeckers were only recorded once in the two visits at those two sites. The reason for this species’ occurrence can also be the structure of pre-rotation aged stands and that those stands can be part of their home range. The size of this species’ home range can be between 4.2 and 33.3 ha in Central Europe (del Hoyo et al. 2002).

In a study on insectivorous birds in a system of old and secondary oak forests with black locusts, Laiolo et al. (2003) concluded that from a conservation perspective, it would be beneficial to not cut black locust trees, but rather to allow the trees to age and die naturally, particularly since black locusts resprout well after cutting. Numerous studies have shown that ageing and dying black locust stands can be suppressed by native vegetation (Motta et al. 2009). In the situation reported in our study, the function of plantations is purely economical and, thus, under such suboptimal conditions, black locust trees typically collapse after 30–50 years and so they will not be older than the rotation time.

Black locust is considered to be one of the most significant invasive species in European woodlands (Kroftová and Reif 2017; Wagner et al. 2017; Campagnaro et al. 2018). The planting of this species is controversial, as it is economically beneficial, both because of timber production and by the honey produced from its nectar. Moreover, the species is highly adaptable and fast-spreading both generatively and vegetatively on arid soils, as well as being a nitrogen-fixing pioneer (Cierjacks et al. 2013; Vítková et al. 2017).

Enescu and Dănescu (2013) stated that black locust could be a solution for land reclamation in arid landscapes in the face of climate change, but also should be managed with great care in the vicinity of protected landscapes as its plantation also mean great biodiversity loss comparing to nearby native habitats (Kroftová and Reif 2017). Climate change could foster the invasion of black locust with increasing aridity of landscapes and, thus, this species has the potential to transform even protected areas that are now out of concern (Kleinbauer et al. 2010). By global warming, black locust could pose a potential threat to even non-arid habitats such as riparian forests (Nadal-Sala et al. 2019).

Two pine species that have been planted in the study region include the Scots pine and the Austrian pine (P. nigra). The former has a wide distribution from Spain to East Asia, while the latter is native to the high elevations of southern Europe (Farjon 2013). Both species are allochthonous to the Great Hungarian Plain (Gencsi and Vancsura 1997; Gardner 2013). The planting of pine species is controversial as the environmental circumstances make this region suboptimal for the plantation of pine species, such forests can only be rejuvenated by soil preparation. In one hand, it prevents soil erosion, ameliorates and shades the soil, but in the other hand, these species suppress native communities, the plantations have low diversity, extreme fire risk and high risk of invasion (Cseresnyés and Tamás 2014). These pine stands cannot be rejuvenated by coppicing, but only by plantation combined with soil disturbance.

These non-native forests are at the margin of their tolerance with poor growth characteristics and low economic value. Non-native coniferous plantations have negative effects on the native forest communities. With the ageing of the stands, this effect could be mitigated, but short-rotation harvesting could mean serious drawbacks for the survival of native tree species (Brockerhoff et al. 2003; Sweeney et al. 2010a). We found that pine plantations were one of the poorest habitats for birds of this plantation matrix, largely because of their inability to decompose leaf litter, their poor under- and midstorey levels, and among other factors, the resin of pines inhibits cavity formation in living trees (Conner et al. 2001). Coniferous stands, hybrid poplar and black locust plantations in our study also harboured lower total abundance, diversity, and species richness relative to old oak remnants, with most consisting of habitat generalists such as common chaffinch (Graham et al. 2014) and species that prefer open forests such as Eurasian golden oriole, spotted flycatcher, and tree pipit (Pedley et al. 2019). Pine plantations also provide nesting habitat for specialists of coniferous forests such as coal tits (Sweeney et al. 2010a; Winkler and Erdő 2012).

Cavity-nesting species in our study occurred in lower abundances in pine plantations compared to old oak forests as has been found in similar studies conducted in a variety of Mediterranean oak habitats and pine plantations in Italy (de Gasperis et al. 2016), in pedunculate oak forests and coniferous plantations in Ireland (O'Connell et al. 2012). In a study conducted in oak forests and coniferous plantations in Turkey, both cavity- and ground-nesters were more abundant in oak forests, as the understory layer of coniferous plantations is scarce, and older stands had positive effects on avian diversity (Walankiewicz et al. 2014; Bergner et al. 2015). The authors of the Turkey study recommended that managers increase the number of old trees in plantations, and also retain the understory layer, to enrich the habitat structures for breeding forest birds. On top of this, forestry practices that manage for continuous understory cover should be implemented (Calladine et al. 2015). Retention of native trees in coniferous plantations or creating mixed-species plantations would also benefit forest birds (Barrientos 2010; Sweeney et al. 2010b; Hanzelka and Reif 2016). To mitigate the effects of clear-cutting of native plantations, green-tree retention should also be promoted to conserve native forest bird communities, and thereby leaving old, decaying trees with tree holes and diverse microhabitats as ‘legacy trees’ (Machar et al. 2019).

Mature non-native plantations with higher structural diversity can provide nesting habitat for more diverse forest bird communities (Hanzelka and Reif 2016; Rodríguez-Perez et al. 2018). Mixed-species plantations can also mitigate the effects of non-native plantations on forest avifauna, but only to a lesser extent, compared with natural or semi-natural old oak forest stands (Hanzelka and Reif 2016; O'Connell et al. 2012). In the situation presented in this study, the constraints of short rotation times and monocultural practices preclude other forms of forest management. Moreover, the suboptimal environmental sources in the region will likely results in collapse when such plantations reach 30 − 50 years of age.

Conclusion

Old oak remnants were the most optimal habitats for forest birds among the forest types studied both in terms of age of stands and by diverse forest structure. Such old oak forests serve as source habitats for avian bird diversity in the region. Most sensitive to old oak forest loss were ground foragers, bark foragers, cavity-nesters, residents, and Mediterranean migratory birds. Native plantations were better habitats relative to non-native plantations but if present forestry practices continue, including further fragmentation of old oak remnants, forest plantations will lose bird diversity in old oak stands. These old oak forest remnants are among the last remaining, critically endangered stands of this particular habitat type in the Pannonian forest steppe region (Rédei et al. 2020). The disappearance of such high diversity remnants would have negative effects on native avian communities within forest plantation matrices, resulting in local extinctions of forest specialist species, thus magnifying the importance of such habitats to conservation initiatives (Noh et al. 2019).

References

Akaike H (1973) Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Petrow BN, Csaki F (Eds) Proceedings of the 2nd international symposium on information. Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest, pp 267–281

Barrientos R (2010) Retention of native vegetation within the plantation matrix improves its conservation value for a generalist woodpecker. For Ecol Manag 260(5):595–602

Bergner A, Avcı M, Eryiğit H, Jansson N, Niklasson M, Westerberg L, Milberg P (2015) Influences of forest type and habitat structure on bird assemblages of oak (Quercus spp.) and pine (Pinus spp.) stands in southwestern Turkey. For Ecol Manag 336:137–147

Biró M, Révész A, Molnár Z, Horváth F, Czúcz B (2008) Regional habitat pattern of the Danube-Tisza Interfluve in Hungary II: the sand, the steppe and the riverine vegetation, degraded and regenerating habitats, regional habitat destruction. Acta Bot Hung 50(1–2):19–60

Bölöni J, Molnár Z, Biró M, Horváth F (2008) Distribution of the (semi-) natural habitats in Hungary II. Woodlands and shrublands. Acta Bot Hung 50(Suppl. 1):107–148

Borhidi A (1999) A hazai növénytársulások veszélyeztetettsége és védettsége. In: Borhidi A, Sánta A (eds) Vörös Könyv Magyarország növénytársulásairól 1. Természetbúvár, Budapest, pp 65–78 (In Hungarian)

Bremer LL, Farley KA (2010) Does plantation forestry restore biodiversity or create green deserts? A synthesis of the effects of land-use transitions on plant species richness. Biodivers Conserv 19(14):3893–3915

Brockerhoff EG, Ecroyd CE, Leckie AC, Kimberley MO (2003) Diversity and succession of adventive and indigenous vascular understorey plants in Pinus radiata plantation forests in New Zealand. For Ecol and Manag 185(3):307–326

Brooks ME, Kristensen K, van Benthem KJ, Magnusson A, Berg CW, Nielsen A, Skaug HJ, Maechler M, Bolker BM (2017) glmmTMB balances speed and flexibility among packages for zero-inflated generalized linear mixed modeling. R J 9(2):378–400

Buchwald E (2005) A hierarchical terminology for more or less natural forests in relation to sustainable management and biodiversity conservation. In: Proceedings of FAO Third expert meeting on harmonizing forest-related definitions for use by various stakeholders on Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome, pp 17–19

Calladine J, Bray J, Broome A, Fuller RJ (2015) Comparison of breeding bird assemblages in conifer plantations managed by continuous cover forestry and clearfelling. For Ecol Manag 344:20–29

Campagnaro T, Brundu G, Sitzia T (2018) Five major invasive alien tree species in European Union forest habitat types of the Alpine and Continental biogeographical regions. J Nat Conserv 43:227–238

Camprodon J, Faus J, Salvanyà P, Soler-Zurita J, Romero JL (2015) Suitability of poplar plantations for a cavity-nesting specialist, the lesser spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos minor, in the Mediterranean mosaic landscape. Acta Ornithol 50(2):157–170

Carnus JM, Parrotta J, Brockerhoff E, Arbez M, Jactel H, Kremer A, Lamb D, O’Hara K, Walters B (2006) Planted forests and biodiversity. J For 104(2):65–77

Ceia RS, Ramos JA (2016) Birds as predators of cork and holm oak pests. Agrofor Syst 90(1):159–176

Chaudhary A, Burivalova Z, Koh LP, Hellweg S (2016) Impact of forest management on species richness: global meta-analysis and economic trade-offs. Sci Rep 6:23954. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep23954

Cierjacks A, Kowarik I, Joshi J, Hempel S, Ristow M, von der Lippe M, Weber E (2013) Biological flora of the British Isles: Robinia pseudoacacia. J Ecol 101(6):1623–1640

Conner R, Rudolph DC, Walters JR (2001) The red-cockaded woodpecker: surviving in a fire-maintained ecosystem. University of Texas Press, Austin, p 400

Coote L, Dietzsch AC, Wilson MW, Graham CT, Fuller L, Walsh AT, Irwin S, Kelly DL, Mitchell FJG, Kelly TC, O’Halloran J (2013) Testing indicators of biodiversity for plantation forests. Ecol Indic 32:107–115

Cseresnyés I, Tamás J (2014) Evaluation of Austrian pine (Pinus nigra) plantations in Hungary with respect to nature conservation – A review. Tájökológiai Lapok 12(2):267–284

Czeszczewik D, Zub K, Stanski T, Sahel M, Kapusta A, Walankiewicz W (2015) Effects of forest management on bird assemblages in the Bialowieza Forest. Poland iFor 8(3):377–385

De Cáceres M, Legendre P (2009) Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology 90(12):3566–3574

De Cáceres M, Legendre P, Moretti M (2010) Improving indicator species analysis by combining groups of sites. Oikos 119:1674–1684

de Gasperis SR, De Zan LR, Battisti C, Reichegger I, Carpaneto GM (2016) Distribution and abundance of hole-nesting birds in Mediterranean forests: impact of past management patterns on habitat preference. Ornis Fenn 93(2):100–110

del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Sargatal J (eds) (2002) Handbook of the birds of the world. Jacamars to woodpeckers, Lynx Edicions, Barcelona

Domínguez J, Carbonell R, Ramírez A (2017) Seasonal changes in habitat selection by a strict forest specialist, the middle spotted woodpecker (Leiopicus medius), at its southwestern boundary: implications for conservation. J Ornithol 158(2):459–467

Domokos E, Cristea V (2014) Effects of managed forests structure on woodpeckers (Picidae) in the Niraj valley (Romania): woodpecker populations in managed forests. North-West J Zool 10(1):110–117

Domokos E, Domokos J (2016) Bird communities of different woody vegetation types from the Niraj Valley. Romania Turk J Zool 40(5):734–742

Dufrêne M, Legendre P (1997) Species assemblages and indicator species: the need for a flexible asymmetrical approach. Ecol Monogr 67(3):345–366

Duguid MC, Morrell EH, Goodale E, Ashton MS (2016) Changes in breeding bird abundance and species composition over a 20 year chronosequence following shelterwood harvests in oak-hardwood forests. For Ecol Manag 376:221–230

EC (2021) Nature and biodiversity: the Pannonian Region. https://ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/natura2000/biogeog_regions/pannonian/. Accessed on 18 Jan 2021

EEC (2009) Directive 2009/147/ECof the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 November 2009 on the conservation of wild birds on the conservation of wildbirds (codified version). Off J L20:7–25

Enescu CM, Danescu A (2013) Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.)—an invasive neophyte in the conventional land reclamation flora in Romania. Bull Transilv Univ Brasov Ser II, For, Wood Ind, Agric Food Eng 6(2):23–30

Erdős L, Ambarlı D, Anenkhonov OA, Bátori Z, Cserhalmi D, Kiss M, Kröel-Dulay G, Liu H, Magnes M, Molnár Z, Naqinezhad A, Semenishchenkov YA, Tölgyesi C, Török P (2018) The edge of two worlds: a new review and synthesis on Eurasian forest-steppes. App Veg Sci 21(3):345–362

Farjon A (2013) Pinus nigra. The IUCN Red List of threatened species 2013: e.T42386A2976817

Farwig N, Sajita N, Böhning-Gaese K (2008) Conservation value of forest plantations for bird communities in western Kenya. For Ecol Manag 255(11):3885–3892

Felton A, Hedwall PO, Lindbladh M, Nyberg T, Felton AM, Holmström E, Wallin I, Löf M, Brunet J (2016) The biodiversity contribution of wood plantations: contrasting the bird communities of Sweden’s protected and production oak forests. For Ecol Manag 365:51–60

Fulco E, Tellini Florenzano G (2008) Composizione e struttura della comunità ornitica nidificante in una faggeta della Basilicata. Avocetta 32:55–60 (In Italian)

Gao T, Nielsen AB, Hedblom M (2015) Reviewing the strength of evidence of biodiversity indicators for forest ecosystems in Europe. Ecol Indic 57:420–434

Gardner M (2013) Pinus sylvestris. the IUCN Red List of threatened species 2013: e.T42418A2978732.

Gencsi L, Vancsura R (1997) Dendrológia. Mezőgazda Kiadó, Budapest (In Hungarian)

Graham CT, Wilson MW, Gittings T, Kelly TC, Irwin S, Sweeney OFM, O’Halloran J (2014) Factors affecting the bird diversity of planted and semi-natural oak forests in Ireland. Bird Study 61(3):309–320

Hansen AJ, Spies TA, Swanson FJ, Ohmann JL (1991) Conserving biodiversity in managed forests. Bioscience 41(6):382–392

Hansson L (1992) Requirements by the great spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos major for a suburban life. Ornis Svecica 2(1):1–6

Hanzelka J, Reif J (2015) Responses to the black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) invasion differ between habitat specialists and generalists in central European forest birds. J Ornithol 156(4):1015–1024

Hanzelka J, Reif J (2016) Effects of vegetation structure on the diversity of breeding bird communities in forest stands of non-native black pine (Pinus nigra A.) and black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) in the Czech Republic. For Ecol Manag 379:102–113

Hebda G, Wesołowski T, Rowiński P (2017) Nest sites of a strong excavator, the great spotted woodpecker Dendrocopos major, in a primeval forest. Ardea 105(1):61–71

Hoekstra JM, Boucher TM, Ricketts TH, Roberts C (2005) Confronting a biome crisis: global disparities of habitat loss and protection. Ecol Lett 8(1):23–29

Horák J, Brestovanská T, Mladenović S, Kout J, Bogusch P, Halda JP, Zasadil P (2019) Green desert?: biodiversity patterns in forest plantations. For Ecol Manag 433:343–348

Hothorn T, Bretz F, Westfall P (2008) Simultaneous inference in general parametric models. Biom J 50(3):346–363

Kleinbauer I, Dullinger S, Peterseil J, Essl F (2010) Climate change might drive the invasive tree Robinia pseudacacia into nature reserves and endangered habitats. Biol Conserv 143(2):382–390

Kosiński Z, Kempa M (2007) Density, distribution and nest-sites of woodpeckers (Picidae) in a managed forest of Western Poland. Pol J Ecol 55(3):519–533

Kroftová M, Reif J (2017) Management implications of bird responses to variation in non-native/native tree ratios within central European forest stands. For Ecol Manag 391:330–337

Laiolo P, Caprio E, Rolando A (2003) Effects of logging and non-native tree proliferation on the birds overwintering in the upland forests of north-western Italy. For Ecol Manag 179(1–3):441–454

Lenth R (2020) Emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means. R package version 1.4.7. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

Löf M, Brunet J, Filyushkina A, Lindbladh M, Skovsgaard JP, Felton A (2016) Management of oak forests: striking a balance between timber production, biodiversity and cultural services. Int J Biodivers Sci Ecosyst Serv Manag 12(1–2):59–73

Machar I, Schlossarek M, Pechanec V, Uradnicek L, Praus L, Sıvacıoğlu A (2019) Retention forestry supports bird diversity in managed, temperate hardwood floodplain forests. Forests 10(4):300. https://doi.org/10.3390/f10040300

Magura T, Báldi A, Horváth R (2008) Breakdown of the species-area relationship in exotic but not in native forest patches. Acta Oecol 33(3):272–279

Martín-García J, Barbaro L, Diez JJ, Jactel H (2013) Contribution of poplar plantations to bird conservation in riparian landscapes. Silva Fenn 47(4):1043

Molnár Z, Biró M, Bartha S, Fekete G (2012) Past trends, present state and future prospects of Hungarian forest-steppes. In: Werger M, van Staalduinen M (eds) Eurasian steppes. Ecological problems and livelihoods in a changing world plant and vegetation, Springer, Dordrecht

Motta R, Nola P, Berretti R (2009) The rise and fall of the black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) in the “Siro Negri” Forest Reserve (Lombardy, Italy): lessons learned and future uncertainties. Ann For Sci 66(4):1–10

Nadal-Sala D, Hartig F, Gracia CA, Sabaté S (2019) Global warming likely to enhance black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia L.) growth in a Mediterranean riparian forest. For Ecol Manag 449:117448. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2019.117448

Nájera A, Simonetti JA (2010) Enhancing avifauna in commercial plantations. Conserv Biol 24(1):319–324

Noh JK, Echeverría C, Pauchard A, Cuenca P (2019) Extinction debt in a biodiversity hotspot: the case of the Chilean winter rainfall-Valdivian forests. Landsc Ecol Eng 15(1):1–12

O’Connell S, Irwin S, Wilson MW, Sweeney OFM, Kelly TC, O’Halloran J (2012) How can forest management benefit bird communities? Evidence from eight years of research in Ireland. Irish For 69(1–2):44–57

Olano M, Aierbe T, Beñaran H, Hurtado R, Ugarte J, Urruzola A, Vázquez J, Ansorregi F, Galdos A, Gracianteparaluceta A, Fernández-García JM (2015) Black woodpecker Dryocopus martius (L., 1758) distribution, abundance, habitat use and breeding performance in a recently colonized region in SW Europe. Munibe Cienc Nat 63:49–71

Paillet Y, Bergès L, Hjältén J, Ódor P, Avon C, Bernhardt-Römermann M, Rienk-Jan B, De Bruyn L, Fuhr M, Grandin U, Kanka R, Lundin L, Luque S, Magura T, Matesanz S, Mészáros I, Sebastià MT, Schmidt W, Standovár T, Tóthmérész B, Uotila A, Valladares F, Vellak K, Virtanen R (2010) Biodiversity differences between managed and unmanaged forests: meta-analysis of species richness in Europe. Conserv Biol 24(1):101–112

Pedley SM, Barbaro L, Guilherme JL, Irwin S, O’Halloran J, Proença V, Sullivan MJ (2019) Functional shifts in bird communities from semi-natural oak forests to conifer plantations are not consistent across Europe. PLoS ONE 14(7):e0220155. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220155

Proença VM, Pereira HM, Guilherme J, Vicente L (2010) Plant and bird diversity in natural forests and in native and exotic plantations in NW Portugal. Acta Oecol 36(2):219–226

Quine CP, Fuller RJ, Smith KW, Grice PV (2007) Stand management: a threat or opportunity for birds in British woodland? Ibis 149:161–174

R Core Team (2020) R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Ranius T, Niklasson M, Berg N (2009) Development of tree hollows in pedunculate oak (Quercus robur). Forest Ecol Manag 257(1):303–310

Rédei T, Csecserits A, Lhotsky B, Barabás S, Kröel-Dulay G, Ónodi G, Botta-Dukát Z (2020) Plantation forests cannot support the richness of forest specialist plants in the forest-steppe zone. For Ecol Manag 461:117964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2020.117964

Riffell SAM, Verschuyl J, Miller D, Wigley TB (2011) A meta-analysis of bird and mammal response to short-rotation woody crops. Gcb Bioenergy 3(4):313–321

Robles H, Ciudad C, Matthysen E (2011) Tree-cavity occurrence, cavity occupation and reproductive performance of secondary cavity-nesting birds in oak forests: the role of traditional management practices. For Ecol Manag 261(8):1428–1435

Rodríguez-Pérez J, Herrera JM, Arizaga J (2018) Mature non-native plantations complement native forests in bird communities: canopy and understory effects on avian habitat preferences. Forestry 91(2):177–184

Sheldon FH, Styring A, Hosner PA (2010) Bird species richness in a Bornean exotic tree plantation: a long-term perspective. Biol Conserv 143(2):399–407

Sweeney OFM, Wilson MW, Irwin S, Kelly TC, O’Halloran J (2010a) Are bird density, species richness and community structure similar between native woodlands and non-native plantations in an area with a generalist bird fauna? Biodivers Conserv 19(8):2329–2342

Sweeney OFM, Wilson MW, Irwin S, Kelly TC, O’Halloran J (2010b) The influence of a native tree species mix component on bird communities in non-native coniferous plantations in Ireland. Bird Study 57(4):483–494

Torras O, Gil-Tena A, Saura S (2012) Changes in biodiversity indicators in managed and unmanaged forests in NE Spain. J For Res 17(1):19–29

Turkalj J (2017) Songbird communities in riparian forest and poplar plantations in the Special Nature Reserve Upper Danube. Larus-Godišnjak Zavoda za ornitologiju Hrvatske akademije znanosti i umjetnosti 52(1):49–64

Vítková M, Müllerová J, Sádlo J, Pergl J, Pyšek P (2017) Black locust (Robinia pseudoacacia) beloved and despised: a story of an invasive tree in Central Europe. For Ecol Manag 384:287–302

Wagner V, Chytrý M, Jiménez-Alfaro B, Pergl J, Hennekens S, Biurrun I, Knollová I, Berg C, Vassilev K, Rodwell JS, Škvorc Ž, Jandt U, Ewald J, Jansen F, Tsiripidis I, Botta-Dukát Z, Casella L, Attorre F, Rašomavičius V, Ćušterevska R, Schaminée JHJ, Brunet J, Lenoir J, Svenning JC, Kącki Z, Petrášová-Šibíková M, Šilc U, García-Mijangos I, Campos JA, Fernández-González F, Wohlgemuth T, Onyshchenko V, Pyšek P (2017) Alien plant invasions in European woodlands. Divers Distrib 23(9):969–981

Walankiewicz W, Czeszczewik D (2005) Wykorzystanie osiki Populus tremula przez ptaki w drzewostanach pierwotnych Białowieskiego Parku Narodowego [Use of Aspen Populus tremula by birds in primeval stands of the Białowieża National Park]. Notatki Ornitologiczne 46:9–14 (In Polish)

Walankiewicz W, Czeszczewik D, Stański T, Sahel M, Ruczyński I (2014) Tree cavity resources in spruce-pine managed and protected stands of the Białowieża Forest. Poland Nat Areas J 34(4):423–428

Wesołowski T, Czeszczewik D, Hebda G, Maziarz M, Mitrus C, Rowiński P (2015) 40 years of breeding bird community dynamics in a primeval temperate forest (Białowieża National Park, Poland). Acta Ornithol 50(1):95–121

Winkler D, Erdő Á (2012) A comparative study of breeding bird communities in representative habitats of the Sárosfő Nature Reserve area. Natura Somogyiensis 22:213–222

Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker NJ, Saveliev AA, Smith GM (2009) Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. Springer, New York, p 574

Acknowledgements

Open access funding provided by University of Sopron. We would like to express our gratitude to members of local hunting and forestry companies, and landowners, who helped on the fieldwork. We would like to also thank Dorota Czeszczewik, who made useful comments on both the planning of the study and on the making of the manuscript, as an expert on point count studies and Walter D. Koenig, who made the language corrections. We also thank Anikó Csecserits, who made the study map and Péter Ódor of his professional advice. GÓ was funded by LIFE16NAT/IT/000245 and OeAD-GmbH - ICM-2020-00204, ZB-D and TR were funded by GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00019.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Project funding: This work was supported financially by the projects (LIFE16NAT/IT/000245); (OeAD-GmbH - ICM-2020-00204); and GINOP-2.3.2-15-2016-00019.

The online version is available at http://www.springerlink.com

Corresponding editor: Yanbo Hu.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ónodi, G., Botta-Dukát, Z., Winkler, D. et al. Endangered lowland oak forest steppe remnants keep unique bird species richness in Central Hungary. J. For. Res. 33, 343–355 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-021-01317-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-021-01317-9