Abstract

Conflicts over land use and their resolution are one of the core challenges in reaching sustainable development today. The aim of this paper is to better understand the mechanisms that underlie conflict resolution. To do so we focus on the use and integration of different knowledge types for conflict resolution in three fields: natural resource management, transdisciplinary research and urban planning. We seek to understand what role different types of knowledge have in the different examples and contexts given. How is knowledge conceptualized and defined? How is it used and integrated to resolve conflicts? These questions are answered through a thematic review of the literature and a discussion of the different knowledge typologies from the respective research fields. We compare conflict resolution approaches and, as a synthesis, present an interdisciplinary knowledge typology for conflict resolution. We find that knowledge use centered approaches are seen as facilitating a common understanding of a problem and creating a necessary base for more productive collaboration across disciplines. However, it is often unclear what knowledge means in the studies analyzed. More attention to the role that different knowledge types have in conflict resolution is needed in order to shed more light on the possible shortcomings of the resolution processes. This might serve as a base to improve conflict resolution towards more lasting, long-term oriented and therefore more sustainable solutions. We conclude that the three literatures inform and enrich each other across disciplinary boundaries and can be used to develop more refined approaches to understanding knowledge use in conflict analysis and resolution.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Conflicts over land use are one of the core challenges in reaching sustainable development today (Owens and Cowell 2011; von der Dunk et al. 2011; Raco and Lin 2012; Antonson et al. 2016). The ways in which conflicts are managed are decisive for social justice, human rights, democratic participation and long-term environmental protection and conservation, all of which are foundations of sustainable development as well central issues within the newly launched United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (Owens and Cowell 2011; SDGs, UN 2015). A number of approaches from different subject areas and theoretical traditions focus on conflicts both implicitly, through collaboration and consensus building (i.e., in urban planning and transdisciplinary knowledge production research), and explicitly, in studies of conflict resolution and mitigation (i.e., in natural resource management and environmental governance) (Innes and Booher 2015; Stepanova 2013, 2015).

For example, while conflict is a given starting point for the urban planning (UP) discourse, it has most often been approached in terms of communication, collaboration and consensus building, as well as in terms of emancipation and agonism regarding the role of power relations and domination in planning processes and outcomes (Fainstein 2000; Harvey 2008; Healey 1997; Innes and Booher 2003, 2010; Mouffe 2005; Owens and Cowell 2011). A few recent studies present more in-depth analyses of the processes that specifically constitute conflict development and resolution (e.g., Coppens 2014; Antonson et al. 2016; Kombe 2010).

In contrast, in natural resource management (NRM) and environmental governance, conflicts over natural resources, land use and their resolution have been intensively studied as such (Shmueli 2008; Reed et al. 2011; Stepanova and Bruckmeier 2013; Martín-Cantarino 2010). A few recent studies from within environmental management (e.g., Blythe and Dadi 2012; Stepanova 2013; Butler et al. 2015) suggest that a hitherto neglected component of knowledge integration might be one of the key elements to support conflict resolution on the way to sustainability. Similarly, the importance of knowledge integration as a crucial component for “societal problem solving” in urban planning, is highlighted in studies on transdisciplinary research (TDR) (Bergmann et al. 2012; Burger and Kamber 2003; Godemann 2008; Pohl et al. 2010; Polk 2015a, b). In these studies, integration of multiple knowledge types from diverse sources is presented as central for sustainable development, resource management and planning.

The integration of different knowledges is especially important for the management and governance of complex issues, including conflict resolution with multiple actors. Research suggests that the integration of different knowledges may help to manage the complexity of conflicts by stimulating different kinds of awareness among the actors, e.g., complexity awareness, awareness of different perspectives and critical knowledge gaps, and whole system awareness (Jordan 2014, p. 60; Wouters et al. 2018). For example, complexity awareness helps to “select strategically central aspects of the issue complex and develop effective action plans” for which the actors usually need “a thorough understanding of conditions and causality” (Jordan 2014, p. 60). Integration of knowledge may facilitate common understanding of the problem at hand, its causes, help anticipate consequences and develop proposals for actions (ibid.; Andersson 2015).

The aim of this paper is to increase our understanding of one of the mechanisms that underlie conflict resolutionFootnote 1, namely knowledge integration, through a focus on the definitions and use of different types of knowledge. To do so, we compare different practices of knowledge use for conflict resolution that are dispersed in the NRM, TDR and UP literatures. By practices of knowledge use, we mean how different knowledges are defined in the literature, and how they are used and integrated in conflict resolution. Thus, the practice of knowledge use is seen as subordinate to mechanisms of conflict resolution. By focusing on definitions of knowledge and its use and integration, we draw attention to the ways that these three scholarly areas see and use knowledge in processes of conflict resolution. Knowledge integration as a mechanism of conflict resolution, is an important but under-investigated link between the knowledge types and the methods of conflict resolution (i.e., tools and approaches, e.g., participation). Both topics receive attention in the literature, however in different degrees of analytical depth and detail. By focusing on knowledge types, we hope to contribute to providing insight into the knowledge use related mechanisms of conflict resolution, which can further inform the development of more refined analytical tools for conflict analysis.

Overall, we seek to understand what role knowledge has in the different examples and contexts given. How is knowledge conceptualized and defined? How is it used and integrated to resolve conflicts? These questions are answered through a thematic review of the literature and a discussion of the different approaches to knowledge use and integration that exist in these research fields. As a synthesis, we present an interdisciplinary knowledge typology, which relates the findings from the review of these literatures to each other.

Building upon the work that has been done in NRM, TDR and UP, we discuss how the integration of these three literatures can be used to develop more refined approaches to conflict analysis and resolution. We believe that the topic of conflict analysis and resolution together with the discussion of practices of knowledge use that constitute resolution strategies, will be of interest for a broad scholarship of sustainability science. This integrative approach in turn has the potential to further our analysis and understanding of collaboration and to contribute to more informed and sustainable management practice (SDGs, UN 2015).

The paper proceeds as follows. We present a thematic literature review guided by the question: how are conflict resolution and practices of knowledge use addressed in the respective disciplines? Based on this review we trace and compare the role that different knowledge types and knowledge use processes are given in the respective areas. Finally, we present a synthesis of the reviewed literature and different knowledge typologies that represent the NRM, TDR and UP research fields. In the concluding discussion, we suggest ways in which studies of conflict resolution may benefit from this broader interdisciplinary discussion.

Conceptual base

As noted above, studies of non-violent resource use conflicts (e.g., land use), are spread across disciplines from UP to NRM and environmental governance. The terminology used to address conflicts differs across different approaches. Similar to the term conflict, the terms knowledge and knowledge integration are defined and understood differently in different disciplines and studies. The varying definitions and understandings of the terms imply difficulties when searching for texts to review (Nursey-Bray et al. 2014; Reed et al. 2010). We will therefore start by clarifying how these terms are defined in our study, both for the purpose of methodological clarity and to facilitate the analysis.

Conflict resolution

Conflict is a term that captures diverging interests or disagreements and is referred to in a number of ways including: dispute, clash of interests, competing interests or simply problem. Conflict resolution is also referred to in different ways, for example as conflict prevention, mitigation, management, transformation, consensus building, cooperation, reconciliation, and collaboration. In this paper, we use the term conflict, to refer to local non-violent resource use conflicts that arise around the use of natural resources, primarily land, and to a lesser extent other natural resources, such as different species. High levels of complexity characterize such conflicts including multiple stakeholders with different interests, values and knowledge who are associated with a variety of political and administrative contexts and levels. In the context of UP, conflicts occur when a planned change in land use infringes upon the interests and values of different stakeholders to such a degree that they cannot accept the change without some sort of negotiation. Here, conflict is broadly understood as a situation where stakeholders have incompatible interests related to certain geographically defined land-use units or resource (von der Dunk et al. 2011).

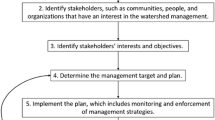

Conflict resolution in the context of NRM and urban planning is a process where a variety of approaches, methods, policy and management instruments are applied. These include formal and informal resolution, governmental and user based procedures, as well as other types of arbitration and mediation, which are direct and indirect, legally enforced and voluntary, knowledge based or culture specific, or a combination of these (Stepanova 2015). Throughout this paper conflict resolution is understood as a dynamic iterative process where different stakeholders (not only courts and mediators) initiate attempts to solve the conflict formally and informally in search of “better” management solutions. In this process, stakeholders co-produce, test, use and integrate different knowledge types (Blackmore 2007; Collins et al. 2007).

Knowledge integration

Knowledge and its integration from different scientific disciplines and non-scientific sources (e.g., local knowledge, professional knowledge) is the theme that is common for all three research fields discussed in this paper: NRM, TDR and UP. Practices of knowledge use and integration is one of the main themes in NRM and environmental governance research where they are discussed as necessary preconditions for more adaptive, collaborative and sustainable resource management (Bremer and Glavovic 2013a, b; Bohensky and Maru 2011; Tengö et al. 2014, 2017). Within TDR, knowledge integration is an overall way to deal with wicked, or complex societal problems (Brown et al. 2010; Polk 2015a, b; Scholz and Steiner 2015a, b). While not explicitly focusing on ‘conflict management’ or ‘conflict resolution’ per se, TDR approaches all are based upon the assumption that knowledge integration is a cornerstone for not only understanding conflicts that occur within attempts to reach a more sustainable society, but also for resolving them. The integration of knowledge, expertise and values from both scientific and non-scientific sources is used normatively, balancing diverse opinions and values regarding how goals are defined, and over what types of knowledge and expertise are seen as most applicable to the solution of specific problems. It is also used instrumentally, where different types of integration are seen as necessary for grasping the complexity of wicked problems, as well as seen as having additional process-related (governance) value for solving current and future conflicts (Bergmann et al. 2012; Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn 2007; Polk 2014; Wiek et al. 2012, 2014). Knowledge integration from diverse sources also results in an increase of knowledge about how other organizations and actors understand, formulate and solve problems and can thus contribute to how societal problems can be solved in the future (Spangenberg 2011; Walter et al. 2007; Wiek et al. 2012, 2014). In these ways, the contributions of knowledge integration to solving societal conflicts (in a broad use of the term), is both implicitly as well as explicitly, a cornerstone of the TDR field.

Different types of knowledge and knowledge integration are also central in the planning literature (Rydin 2007; McGuirk 2001; Watson 2014). Rydin (2007), for example, sees the use of knowledge as “a central element in achieving (positive) change through planning” (p. 53) and claims that “the purpose of planning is to handle multiple knowledges” (p. 55). Practices of knowledge exchange, and different forms and practices of knowing are among the central themes in planning which itself is sometimes conceptualized as a practice of knowing (Davoudi 2015). The importance of the conceptualization of knowledge together with the demand to pay more attention to practices of knowledge use in the context of unequal power relations within planning practice has been repeatedly emphasized (Fainstein 2000; McGuirk 2001; Rydin 2007; Owens and Cowell 2011; Flyvbjerg and Richardson 2002).

Knowledge refers to many different entities (Rydin 2007). It is a much used term in the discourses studied here, that is also used analytically and theoretically, sometimes interchangeably and not always clearly defined. This makes it methodologically challenging to track and study its use. In order to untangle the complexity and multifacetedness of the knowledge concept, this paper will build upon Rydin’s conceptualization of knowledge as knowledge claims (Rydin 2007). Following Rydin, we define knowledge as a claim to understanding certain causal relationships. In other words, understanding of the causal relationship between action and impact constitutes the core of a knowledge claim (ibid. p. 53). According to Rydin, a knowledge claim can be distinguished from other claims, e.g., ethical, pragmatic, efficiency or aesthetic. Knowledge claims may be used to support values. Values thus may constitute part of a knowledge claim, and influence it, but for our use here, they are not equal to knowledge. Furthermore, knowledge claims cannot be reduced to experiences even though experience may be a prerequisite to understanding (ibid p. 56; Collins and Evans 2002; Scholz and Steiner 2015a, b). This distinction helps to separate knowledge from values in complex conflicts and provides a basis for more refined tracking and analysis of knowledge use.Footnote 2

Regarding knowledge integration, another distinction has to be made in regard to the relationship between knowledge and learning. Knowledge related processes are difficult to identify and isolate as they are always intertwined with learning (Blackmore 2007). Here, we understand knowledge use as an overarching term that embraces individual learning, joint learning and knowledge co-production. Learning, in turn, includes knowledge integration as an integral part (Ballard et al. 2008). Knowledge integration can also happen on the individual and group level and on different levels of institutional arrangements (e.g., within planning context). In this paper, knowledge integration is understood as the integration of different knowledge claims in a complex social process of knowledge production, synthesis, sharing and learning within planning and decision-making (Godemann 2008; Polk 2015a, b; Stepanova 2013). Knowledge integration can be understood as both a process and an outcome of conflict resolution and participatory decision-making. For the purpose of this paper, the process dimension of knowledge integration is seen as internal and inherent to individual and group learning processes and methodologically difficult to capture without long-term ethnographic studies. The outcome dimension of knowledge integration, while entwined with specific results of learning/co-production processes, can be traced through the implementation and application of different knowledges in decision-making processes and documentation (e.g., through the decisions made, argumentation used). We see the integration of different knowledges (conflicting knowledge claims) in the context of urban planning as expressed in development goals, plans, and other forms in the implementation stage of the decision-making processes.

Given the multifaceted nature of conflicts and their engagement of diverse actors, it is also important to distinguish the multiple contexts or levels where processes of joint learning and knowledge integration occur. Multilevel integration is understood as horizontal and vertical integration of different knowledge types (Rydin 2007). Horizontal integration happens among stakeholders in formal (e.g., routine public consultation within planning where different knowledge claims and interests get manifested and shared) and informal (e.g., open stakeholder forums, informal dialogues) processes of conflict resolution within urban municipal planning. Importantly, horizontal knowledge integration does not “ensure (its) anchoring in respective institutional and political contexts where social change occurs” (Polk 2015a, b:110). Therefore, the need to also study vertical integration which, together with other knowledge types, includes the integration of knowledge from collaborative and participatory processes on the horizontal level of conflict resolution into actual decision-making and public policy on local and regional levels (Stepanova 2013).

Materials and methods

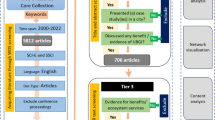

In order to explore how conflict resolution and practices of knowledge use are addressed in NRM, TDR and UP, we thematically reviewed peer-reviewed articles published in English from January 1999 until September 2017.Footnote 3 Only studies published in peer-reviewed journals were included. Books and grey literature (such as reports) were excluded due to the concerns regarding their peer review status and quality. While this delimitation risks missing relevant studies, it nevertheless provides an adequate basis to assess the research in these respective fields for the purpose of this paper.

We applied an iterative search using the search engine Google scholar™ in September–October 2017. This engine was chosen because it returned more results with more complete citation numbers as it includes a wider variety of sources than other search engines. The aim was to first identify studies that directly address conflict resolution in the title, abstract and/or keywords. The keywords for the first search were adapted to the terminology used in respective disciplines. In NRM the keywords were: conflict resolution/knowledge/learning; in TDR: co-production/conflict resolution/joint learning/knowledge integration; in urban planning: conflict resolution/joint learning/knowledge integration/co-production/knowledge use. The results of the first search gave us an overview of how well represented the studies of conflicts and knowledge practices were in the respective disciplines. A second more specific search was made among studies identified in the first round. For this second search, the aim was to distil the studies that discuss practices of knowledge use/integration/learning in relation to /as a strategy for conflict resolution. The keywords applied were knowledge integration/learning/ for conflict resolution. The texts were selected based on the abstract and introduction. A few references were also added from the authors’ wider reading within our research backgrounds (NRM, TDR, UP). These additional references we considered applicable for our purposes as they discussed the themes we were interested in. They were not retrieved through the literature search partly because they dealt with conflict resolution either indirectly or did not use any of the keywords in the title, abstract nor introduction. This was primarily the case for the TD literature, where conflict is not a core concept. In the other areas, the analysis is primarily based on the results retrieved through the organized literature searches. The studies that addressed a combination of the two themes (knowledge integration/use for conflict resolution) were analyzed in more detail. Several exemplary texts were chosen to constitute a base for the discussion of conflict resolution practices in each research area (Tables 1, 2, 3). The chosen texts most fully fulfilled the criteria for the second search. They discussed practices of knowledge use/integration/learning in relation to/as a strategy for conflict resolution, were highly cited, and represented different streams within the respective research areas.

Results

Knowledge use and conflict resolution in natural resource management (NRM)

The theme of conflict resolution has since long been discussed in NRM together with the theme of knowledge use which is central in NRM. Knowledge-based conflict resolution is a basic prerequisite and aim, for example, within adaptive co-management (Plummer et al. 2012, 2017) that includes adaptive management (e.g., Stringer et al. 2006; Pahl-Wostl 2007), collaborative management (e.g., Schusler et al. 2003; Berkes 2009; Mostert et al. 2007), and participatory resource management (e.g., Muro and Jeffrey 2008; Beierle and Konisky 2000).

Conflict, although indirectly, is also at the core within common pool resource research (CPR) and within the social-ecological resilience literature. In CPR, conflict resolution is addressed through deliberation, negotiation, dialogue and joint learning, which is facilitated by innovative institutional arrangements (e.g., Ostrom et al., Adams et al. 2003; Dietz et al. 2003; Paavola 2007; Ratner et al. 2013). In the social-ecological resilience literature, conflicts are treated through social networks, knowledge sharing and social learning (e.g., Lebel et al. 2006; Olsson et al. 2004 on adaptive co-management for resilience). Together with adaptive co-management, more detailed and in-depth studies of conflicts and their resolution are also found within human ecology (Bruckmeier 2005; Bruckmeier and Höj Larsen 2008; Jentoft and Chuenpagdee 2009; Stepanova 2013, 2015) and biological/wildlife conservation (e.g., Dickman 2010; Redpath et al. 2004, 2013; Henle et al. 2008; Madden and McQuinn 2014). In these literatures, conflict resolution is often framed in terms of participation, cooperation, collaboration, dialogue and conflict transformation (Stepanova and Bruckmeier 2013).

Table 1 contains representative studies within NRM that explicitly discuss processes of knowledge use and integration for conflict resolution that were identified in the process of literature review. The resolution approaches discussed in these studies are consensus and compromise oriented and see knowledge sharing and integration through joint learning as a necessary precondition to form a common understanding or interpretations of a problem at hand. The main difference is the level of analysis of conflicts and the way that knowledge integration is theorized or framed. The framing of knowledge integration through social, joint and collaborative learning prevails (Reed et al. 2011; Redpath et al. 2013; Bruckmeier and Höj Larsen 2008; Butler et al. 2015) with the exception of the framing/reframing approach (Emery et al. 2013; Shmueli 2008; Putnam et al. 2003) (Table 1). Joint learning is seen as central for better understanding the positions and perceptions of participating actors. It is also seen to help formulate common goals and paths to reach them (Reed et al. 2011). In slight contrast to other approaches where knowledge integration is conceptualized though learning, in the framing/reframing approach, which may be seen as a process of knowledge integration itself, knowledge production and integration are seen as part of a cognitive process (framing) of understanding, interpreting and making sense of the problem at hand (Shmueli 2008; Emery et al. 2013). However, it may be argued that learning and understanding are interconnected or constitute each other. At the same time, understanding in framing/reframing is also about acceptance (no matter what it is based on) on the way to a trade-off or consensus.

In the NRM literature, the process component of knowledge integration (related to individual and group learning) is rarely analyzed in depth or evaluated. Rather, it is implicitly present in general processes of dialogue, negotiation, learning, collaboration and participation. Joint formulation of alternative resource management plans often constitute the outcome component of knowledge integration. This latter component is given more attention in the studies as a concrete outcome of the resolution efforts, something that consensus may result in.

The knowledge types identified in these studies fall within the general knowledge typology of scientific, expert/managerial, local (ecological) knowledge. For example, Butler et al. (2015) provide an example of successful horizontal and vertical integration of competing knowledges (scientific, managerial, local ecological) in a form of jointly produced alternative management plans formulated in the process of collective negotiations.

Stepanova (2013) offers a more detailed knowledge typology where the three general knowledge types (local, scientific, managerial/administrative) are further categorized as formal or informal, local ecological or local social knowledge.Footnote 4 By informal knowledge, she refers to mainly individual, not documented knowledge communicated in informal forums. Informal knowledge is often integrated in formal knowledge articulated through written documents, norms and procedures.

This review of the NRM literature shows that the authors rarely specify what they mean by knowledge or different knowledge types. In the reviewed studies, the focus is rather on the instrumental processes that stimulate or support knowledge use and integration on different levels of decision-making (concerned with the “how”, “through what strategies and tools”) (i.e., Reed et al. 2011; Butler et al. 2015), rather than on in-depth discussion of the roles that different knowledge types have in conflict resolution and resource management.

Knowledge types and knowledge integration in transdisciplinary research (TDR) and their contributions to conflict resolution

What can the transdisciplinary approaches contribute to using knowledge integration for conflict resolution in urban contexts? The transdisciplinary discourse includes a number of different approaches to knowledge integration. Given that the transdisciplinary discourse itself is interdisciplinary, knowledge integration is framed from within a variety of theoretical and disciplinary approaches. One of the main focus areas in the TDR literature included in our review is the research process itself, how it is characterized, what features it has, what forms it takes, what its goals are and how different degrees and types of participation/collaboration effect societal outcomes (Jahn and Keil 2015; Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn 2008; Talwar et al. 2011; Walter et al. 2007; Wiek et al. 2014; Westberg and Polk 2016; Wickson et al. 2006). Overall, participation and learning (mutual, social, situated) are seen as mechanisms for ensuring sufficient integration of knowledge, expertise and values from different stakeholder groups. TDR thus includes not only discussions regarding knowledge integration, but also focuses on process, and more recently on how power relationships influence the ability to integrate different perspectives into TDR (Berger-González et al. 2016; Klenk and Meehan 2015; Schmidt and Neuburger 2017). For the purpose of this paper, four topics within the TDR literature will be discussed here. These include: conceptual models for collaboration, knowledge typologies, mutual learning processes and participatory features/power (see Table 2).

For the context of conflict resolution in focus in this paper, knowledge integration in the TD discourse is not just about knowledge outcomes, it is about knowledge creating processes, about how knowledge exchange, sharing and integration occur through different types of participation, cooperation and collaboration. A great deal of attention has been put on designing conceptual models for collaboration that can create the premises for knowledge exchange and learning (Jahn et al. 2012; Lang et al. 2012; Morton et al. 2015; Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn 2007; Polk 2015a, b; Wiek et al. 2014). These models focus on designing mechanisms into the research processes that ensure a sufficient amount of knowledge integration to grasp the complexity of the problem under study and represent the expertise of relevant stakeholders. Key strategies include creating joint understanding and problem framing around a common research objects, collaborative knowledge production processes and joint synthesis, implementation and communication of results (Lang et al. 2012; Polk 2015a, b). Central issues for joint understandings and problem formulations include discussions regarding the significant amount of time needed to create the mutual trust and commitment that underlies the creation of productive relationships.

Numerous studies within the TD discourse discuss both knowledge types and their integration (Burger and Kamber 2003; Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn 2007; Pohl 2011; Zierhofer and Burger 2007; Klenk and Meehan 2015; Morton et al. 2015; Hoffmann et al. 2017). Overall, the main distinction of knowledge types is between scientific knowledge and practitioner-based expertise or the so-called science–policy interface (Munoz-Erickson 2014). A number of TD scholars make further distinctions based upon groups of actors, the focus or functions of knowledge, and on knowledge systems or communities. The first is often within the science–practice divide and includes interdisciplinary knowledge integration among different disciplines and scientific domains like the natural and social sciences, and different types of professional or experienced based knowledge based on groups of actors such as bureaucrats, civil servants, business interests or on experiential or lay knowledge (Edelenbos et al. 2011; Enengel et al. 2012; Munoz-Erickson 2014). The second includes knowledge classifications based on the type of analysis being undertaken such as instrumental, normative and predictive (Burger and Kamber 2003; Pohl 2011). The third focuses more on mutual learning processes and includes how knowledge systems are constituted in different communities, collectives and epistemologies (Burger and Kamber 2003; Pohl 2011; Westberg and Polk 2016).

From the Swiss discourse on TDR, Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn present a much-cited typology of knowledge, where systems, target and transformative knowledge are noted as the basic types of knowledge that are needed for TDR for sustainability (Burger and Kamber 2003:52; Proclim 1997; Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn 2007). Systems knowledge refers to knowledge about the current state of a specific problem (How did we get here and where are we heading?); target knowledge refers to desirable futures or goals (Where do we want to go?), and transformative knowledge refers to knowledge about how to transition to a specific goal or future (How do we get there?) (Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn 2007; ProClim 1997). These knowledge types are seen to embody the specific challenges of sustainability, regarding uncertainties, the contested nature of sustainability and the practical and institutional contextual complexity related to reaching sustainability (Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn 2007). These types of knowledge are not based on stakeholder categories, but span both disciplines and actor groups.

Knowledge integration is also approached with a focus on mutual learning processes as well as how this learning occurs within group settings (e.g., Godemann 2008; Westberg and Polk 2016). Here the focus is on the specific aspects of the knowledge/knowing concept and how different types of knowledge/expertise are brought together via, for example creating a common knowledge base, cognitive frame, and shared mental modes through situated and social interactions within a group (Godemann 2008; Schauppenlehner-Kloyber and Penker 2015; Westberg and Polk 2016).

Dealing with power differentials has also been an implicit topic within TDR through analyzing how participatory features enable different degrees of collaboration, t. ex. Talwar et al. (2011), Brandt et al. (2013) and Wiek et al. (2014). There is a growing focus on the impact of power differentials, since the integration of multiple voices and knowledges are a cornerstone of the TD approach (Bracken et al. 2015; Berger-González et al. 2016; Klenk and Meehan 2015). More recent approaches criticize TDR for not adequately dealing with ingrained power differentials between participating groups. For example, approaches from anthropology and science studies criticize what they consider a naive approach to knowledge integration that does not adequately deal with power and their resultant epistemological and cultural differences (Berger-González et al. 2016; Klenk and Meehan 2015).

As this section shows, TDR provides in-depth discussions and reflections over the participation processes that lead to knowledge integration and co-production. It looks into how knowledge integration and co-production happen through in-depth study of the process-related mechanisms and the premises for knowledge exchange and learning.

Knowledge use and conflict resolution in urban planning (UP)

In contrast to TDR where conflict is present indirectly, conflict is widely acknowledged in urban planning literature (Healey 2003; Innes and Booher 2003, 2010, 2015; Owens and Cowell 2011). Conflicts are seen as natural byproducts of the planning process where conflicts of multiple differing interests and goals become manifest. Formal planning procedures are themselves a tool for conflict resolution, which is achieved through both formal (e.g., legal and policy based) and informal procedures that may differ in means and/or form (Zhang et al. 2012). For example, in collaborative planning conflict resolution is an explicit goal (Innes and Booher 2010, 2015). Innes and Booher (2015) argue that “collaboration is about conflict”, they refer to conflict as an engine behind collaboration, because if stakeholders did not have disagreements, they would not need to collaborate (ibid p. 203). In urban collaborative planning, conflicts are addressed through different forms of consensus oriented collaborative efforts, e.g., dialogues, discussions, formal (e.g., public consultation within planning) and informal (e.g., stakeholder forums) participatory procedures.Footnote 5 The resolution procedures aim to generate common/shared perceptions, objectives or understanding among the stakeholders, inform negotiation and decision-making (Ross 2009; Halla 2005; Margerum 2002; Sze and Sovacool 2013).

Together with the conflict theme, the theme of knowledge use, knowledge contestation and plurality of knowledge is also internal to collaborative planning (Sandercock 2003). Knowledge integration, although implicitly addressed, is incorporated in collaborative planning’s striving towards a joint creation of a shared understanding and meaning (Innes and Booher 2015). Different forms of communication and participation, for example collaborative dialogues, group negotiations, open stakeholder forums within collaborative planning serve as arenas for integration of different knowledges (Peltonen and Sairinen 2010; Sun et al. 2016; Domingo and Beunen 2013; Patterson et al. 2003). Shared understanding of the issue at hand is one of the expected outcomes of integration of different knowledge types.

Critical planning scholars, who criticize collaborative planning´s orientation towards consensus, call for more robust deliberation and institutionalization of inclusive participation in order to facilitate transformative learning/integration of knowledges. Transformative learning may expose power relations and widen the scope of the value systems. It may also widen the scope of forms of knowledge and meaning used to inform the formulation of planning aims (Brand and Gaffikin 2007; McGuirk 2001; Mouffe 2005) and lead to a more accurate and meaningful knowledge base for planners to act and make decisions upon (Innes and Booher 2015). Scientific, lay and expert/managerial knowledge types are among the most recognized.

Acknowledging the contribution and relevance of collaborative planning literature for general conflict resolution through collaborative procedures, we find that very few studies explicitly focus on both practices of knowledge integration and conflict resolution. Most of the UP studies reviewed here revolve around collecting or sharing information within the frames of communication, rather than discussing different knowledge types and the processes of their use. However, a few studies also focus explicitly on collective knowledge production and knowledge integration and deem the integration of different knowledge types in collaborative processes as important for conflict resolution or reaching consensus (Ross 2009; Peltonen and Sairinen 2010; Patterson et al. 2003; Golobiĉ and Maruŝiĉ 2007). For example, Peltonen and Sairinen (2010) argue that joint knowledge production (co-creation) and communication of the newly produced knowledge are important elements of the planning process that may help finding new solutions, especially in conflict management. Integration of the three main knowledge types distinguished in these studies—scientific, expert/managerial and lay—is expected to provide an overview or deeper understanding of conflicts and different issues, and help to find common interests and reach consensual solutions (Table 3).

Some examples of the tools applied to facilitate knowledge integration include development of knowledge-based alternative solutions based on integration of local/lay and expert knowledge through creation of “cognitive maps” (models) that are later used for open public debates (Golobiĉ and Maruŝiĉ 2007), and the use of social impact assessment (Peltonen and Sairinen 2010). Through the mediation process, the conflicting parties build a common platform of knowledge which may be further used for formulation of intermediary agreements, trade-offs and decision-making.

This section shows that UP authors see conflicts as a natural part of the planning process where the planning procedure is, itself, a tool for conflict resolution. The theme of knowledge use is internal to the planning process. However, very few studies explicitly focus on how different knowledge types contribute to knowledge integration and conflict resolution simultaneously.

Comparing knowledge use practices for conflict resolution in NRM, TDR and UP

The need to address the challenge to manage multiple knowledge types and claims is evident among the reviewed studies that represent NRM (Blackmore 2007; Henry 2009), TDR (Polk 2015a, b; Godemann 2008; Walter et al. 2007; Wiek et al. 2014; Pohl et al. 2010), and UP within the collaborative planning literature (Healey 1997; Rydin 2007; Innes and Booher 2003, 2015).

Overall, in the NRM literature more refined and defined knowledge types that go beyond the general categories of local/scientific/managerial are rarely discussed in relation to conflict resolution. In the reviewed studies, the focus is primarily on the outcomes of participation and collaboration as the main approaches to resolving conflicts, rather than on processes and mechanisms. The studies are mostly concerned with the instrumental part of conflict resolution, e.g., collaborative and participatory tools, with limited further analysis or evaluation of the processes that happen within these tools.

Similarly, the reviewed UP studies tend to focus on specific tools to facilitate integration/collaboration/communication of knowledge. They do not go into in-depth analyses or discussion of the mechanisms of integration or the roles that different knowledge types have in the process. Neither do the reviewed studies provide an in-depth analytical evaluation of the knowledge integration process in terms of its specific contribution to planning and decision-making. In contrast to NRM and UP, TD specifically focuses on the phases and mechanisms of knowledge integration, with no specific focus on conflict resolution.

Although the reviewed studies and practices of knowledge use do not always explicitly aim to resolve conflicts, they have in common the goal of creating a common/joint understanding of the problem at hand. Common understanding is regarded as one of the cornerstones and prerequisites for reaching a trade-off among the stakeholders; it serves as a basis for more adequate and informed decision-making and, eventually, resolution of conflicts. Collaborative and participatory settings and tools that promote joint learning/joint knowledge production and communication are among the main tools used to facilitate integration of different knowledge types.

However, the degree of attention paid to actual practices of knowledge use and integration differs significantly between the three fields. In NRM and UP the analysis and discussion of knowledge processes often remain on the discursive/rhetorical level or is reduced to the general and largely undefined knowledge types (scientific, local/lay, expert knowledge). Integration of different knowledge types is often pre-understood or implied through the general collaborative and participatory settings and through information exchange (in UP). The processes of integration often remain undiscussed or assumed behind “participation”/“collaboration”. This makes it difficult to see what role collaborative and participatory processes that aim at knowledge integration actually play in conflict resolution.

In cases where knowledge types are part of the discussion in NRM and UP they often remain largely undefined. It is often unclear what authors mean by “knowledge” or specific knowledge types. This highlights the question of what is being integrated in the resolution processes presented in the reviewed studies. The question of how knowledge is used and integrated in the resolution of conflicts in NRM and UP also remains. Overall, our review shows that more elaborated knowledge typologies that could be relevant for conflict resolution in NRM and UP are relatively few (e.g., Raymond et al. 2010; Stepanova 2013; Rydin 2007).

While conflict studies in NRM and UP are somewhat less concerned with the mechanisms of knowledge integration or elaborated knowledge typologies, TDR offers in-depth analyses of and reflection on participatory and learning processes, on process of knowledge integration their goals and forms (e.g., Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn 2007; Burger and Kamber 2003; Pohl 2011 and others mentioned in section on TDR). Conflict studies within NRM and UP could therefore benefit from some of the approaches to knowledge integration developed within TDR to refine the analysis of knowledge use in different types of conflict resolution. Below we present a first attempt to such an interdisciplinary knowledge typology, which combines approaches from NRM, collaborative planning within UP, and TDR (Fig. 1).

Interdisciplinary typology of dominant knowledge types in conflict resolution. Dashed arrows symbolize the tentative distinction between different knowledge types, as in practice they are often intertwined and difficult to separate. Thick, overarching/colored arrows mean that different levels of the typology are interrelated and inform each other. The color is used to facilitate readability and does not have specific meaning.

Synthesis: interdisciplinary knowledge typology for the analysis of conflict resolution

The interdisciplinary knowledge typology, in Fig. 1, presents a combination of knowledge typologies by Stepanova (2013) for conflict resolution in NRM, Rydin (2007) for UP, and by Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn (2007) for TDR. It includes both knowledge types and analytical levels from the respective areas.

Regarding knowledge types, Stepanova identifies informal, formal, local/lay, scientific, administrative/managerial knowledge types, differentiating between different contexts and actors in NRM (Stepanova 2013). Rydin distinguishes five types of planning knowledge based on functional characteristics and knowledge sources. These include process, predictive, normative, empirical, and experiential knowledge types (Rydin 2007). We also add knowledge jointly co-produced by stakeholders in collaborative and participatory settings as an additional type of knowledge that can be traced in resolution processes (Polk 2015a, b; Albrechts 2012). Rydin’s process, predictive and normative knowledge are used in our typology as practice related sub-categories of formal and informal knowledge of different actors, while her categories of empirical/experiential knowledge are merged with the broader category of informal knowledge that is context bound.Footnote 6 Rydin’s categories of process, predictive and normative knowledge also correspond well with the functional knowledge categories suggested by Pohl and Hirsch Hadorn (2007). As outlined earlier, their knowledge types include systems, target and transformative knowledge. We combine these two sets of knowledge categories as they complement each other in their definitions and have strong connections to practice related level of analysis. These knowledge types represent the specific challenges of sustainability regarding uncertainties, normativity and institutional and contextual complexity, and can be traced in practice routines, e.g., documents, visions.

Combining typologies from different fields, shows the different ways that knowledge can be conceptualized and analyzed. In our typology, these different conceptualizations are positioned on different analytical levels: in broader contexts (formal and informal), in institutional affiliations and mandates (individual actors, planning professionals, decision-makers, academics) and in practice related processes, (planning and implementation routines, decision-making processes). The levels of context, actors and practice are the analytical distinctions we will use to structure the analysis of complex conflicts and resolution practices. These analytical levels transform a simple typology into an integrated analytical tool. The different levels of analysis mirror those found in NRM, TD and UP, making it possible to compare knowledge types across discourses and categories and potentially identify gaps in knowledge use and integration in conflict resolution process.

When applied to conflict analysis, the practice level of the typology could serve as a starting point. The practice level is where different knowledge claims that different actors bring into conflicts can be traced, identified and compared (e.g., scientific, professional, local/lay) in relation to practical, predictive and process components of practice. For each practice related knowledge type, one can further identify the more specific knowledge types that actors bring into the discussion (actors level types), because the basis for the claims made explicit on the practice level is different according to the different actors involved. For example, one can compare the target goals from different actors as expressed through the knowledge claims they operate with. Practice related knowledge types are easier to trace in the documents and other sources, which also makes this level a convenient point to start the analysis from. The analytical levels mirror the complexity of conflicts and to some extent thus address the wickedness of the problem at hand. The three analytical levels also embody the theoretical (or analytical) approach that conflict resolution is about how context and actors play out in practice through different types of knowledge claims; that is, in practices of conflict development and resolution.

Positioning these knowledge typologies in terms of levels thus increases our ability to compare the diversity of knowledge conceptualizations and better understand how they relate to the different levels of analysis presented in the reviewed studies.

Presenting the different knowledge types in the form of a typology has its limitations as knowledge types can overlap, be held by different actors, and be integrated into one another. Such limitations become visible for example in case of local and indigenous knowledge. Local knowledge includes indigenous knowledge, but it is difficult to locate it to one specific knowledge type or level. Indigenous knowledge may be local, based on practice, observation, experience, but also professional as it can be concentrated with local “experts”.Footnote 7 It can be about rules, procedures and laws; it can also serve as a basis for decision-making, for example in case of small-scale fisheries, biological conservation, sustainable land use, etc. (Deepananda et al. 2015; Ens et al. 2015; Mistry and Berardi 2016). The fact that indigenous knowledge may also be professional (expert), allows looking at it not only from informal, but also from a formal knowledge perspective. In the case of indigenous knowledge, we recognize it as imbedded in different knowledge systems, which makes it difficult to place in a single knowledge type (Tengö et al. 2017). This example shows how complex knowledge types, while problematic, can still be adequately positioned in multiple places in our typology.

The framework presented in Fig. 1, importantly, is not suited for and does not strive to access the validity of knowledge claims; rather, it aims to help identify the dominant knowledge types articulated by stakeholders during the course of conflict development and resolution. We accentuate “dominant” knowledge types because different stakeholders hold multiple types of knowledge and employ them simultaneously (Negev and Teschner 2013). Nevertheless, knowledge typologies are helpful for identification of the dominant knowledge types articulated by stakeholders in conflict. Whether or not different knowledge types get integrated can only be traced indirectly, through the outcome component of knowledge integration (see Methodology section). This may be seen, for instance, through the change in positions of stakeholders that leads to a jointly accepted solution which may be reflected in documents, policies, alternative management plans, etc. (for examples see e.g., Stepanova 2013; Redpath et al. 2013; Butler et al. 2015; Reed et al. 2011).

The interdisciplinary knowledge typology presented above could serve as a point of departure in mapping the knowledge types used in practices of conflict resolution. When identified, they may be followed further in horizontal collaborative, participatory processes and in vertical processes of integration into decision-making. When tested in practice, the typology must clearly be refined and specified according to contextual needs, because “processes of conflict development, resolution and knowledge use are complex social phenomena which require attention to the context where experiences and meanings are largely bound to time, people and setting” (Baxter and Eyles 1997).

Complementary integration of typologies (such as one suggested in Fig. 1) might help to better analyze what knowledge is marginalized, excluded from or underrepresented in the participatory/collaborative processes, what implications this could have on the outcomes of participation/collaboration, and what implications this could have for long-term oriented conflict resolution and management.

Discussion and conclusions

The aim of this paper is to better understand the mechanisms that underlie conflict resolution through a focus on the use and integration of different knowledge types in three discourses: NRM, TDR and UP. We seek to understand what knowledge refers to in the different examples and contexts, and how knowledge is and can be used and integrated to resolve conflicts. First, based on the thematic review of the literature, we compare conflict resolution approaches in the respective fields and identify common features in relation to how conflict resolution is practiced. In all three discourses, the centrality of participatory and collaborative approaches that promote knowledge exchange and joint learning for conflict resolution is widely acknowledged. Overall, knowledge use centered approaches are seen as facilitating a common understanding of a problem and creating a necessary base for more productive collaboration. However, in some of the reviewed studies, we also identify a general lack of attention to concrete mechanisms and processes that constitute the notions of participation and collaboration of conflict resolution (with a few exceptions of studies that point out that formal participation organized in a mechanistic way is no guarantee for productive learning or collaboration). What is happening during these processes or what needs to happen in participatory processes in order for stakeholders to develop a common understanding of a problem remains under-discussed in NRM and UP where the focus is rather on the outcomes than on processes. In contrast, TDR provides a more in-depth discussion and reflection over the processes that are meant to lead to knowledge integration and co-production. It focuses on phases of knowledge integration, on the integration process itself, its’ premises, mechanisms, forms and goals. TDR also pays more attention to the role the different knowledge types have in this process and in how they affect the outcomes (what they contribute to conflict resolution and decision-making).

Second, we look into how knowledge is seen, defined and used in resolution processes. The thematic review allowed to explore how different knowledges are defined, used and integrated for conflict resolution, planning and solving complex problems in the three scholarly areas of NRM, TD and UP. In the studies analyzed, the practices of knowledge use and integration often remain on a discursive level with largely undefined or pre-understood knowledge types. This limits our ability to see what role different knowledges play in participatory processes and how they specifically contribute to conflict resolution. In some instances (e.g., with TD literature), their use for conflict resolution required interpretation.

We identified some general trends and common practices of knowledge use that directly or indirectly facilitate conflict resolution. For example, it is often unclear what knowledge means in the studies analyzed. When different knowledge types are discussed, the classifications often seem pre-understood and tend to fall into the general and largely undefined categories of scientific, local/lay and managerial/expert knowledge (i.e., it is often not explained what local/lay knowledge is in particular studies and contexts). This lack is to some extent balanced by the discussion of the more or less comprehensive knowledge typologies found in each discourse that go beyond the general knowledge types and provide clearer definitions.

Our interdisciplinary knowledge typology for conflict resolution (Fig. 1) serves as an attempt to integrate approaches from different fields. It is an example of a possible starting point for further research and discussion on how conflict analysis and resolution may be enriched through developing more refined interdisciplinary tools for the analysis of knowledge use practices. Our findings call for more research on knowledge integration processes and mechanisms, and more attention to the evaluation of the role that different knowledge types have in resolution of conflicts. By paying more attention to the question of what knowledge is referring to and how knowledge is used and integrated in resolution practices, more light may be shed on the possible shortcomings of the resolution processes, which might in turn serve as a base to improve conflict resolution towards more lasting, long-term oriented and therefore more sustainable solutions/planning.

In conclusion, these three literatures inform and enrich each other across disciplinary boundaries on the way to developing more refined approaches to conflict analysis and resolution. This in turn has the potential to develop the focus on collaboration and to contribute to more informed and sustainable management practice (SDGs, UN 2015).

Notes

We use this definition of knowledge to facilitate our analysis of the reviewed studies; however, this does not mean that definitions of knowledge used in the reviewed studies are similar to ours.

Such a period is appropriate since the research within communicative planning theory and collaborative planning, where conflict and its resolution is central, started gaining momentum during this time. The NRM and TDR fields are also adequately represented in this period.

For an example of a more comprehensive knowledge typology within environmental management see, e.g. Raymond et al. (2010).

Although scholars representing this line of thought acknowledge that full consensus may not be always possible, such focus has received criticism. The criticism regards collaborative planning orientation towards consensus as being ignorant of inevitable tensions of power in planning realities (Margerum 2002; Owens and Cowell 2011). Collaborative planning scholars meet this criticism arguing that communication power is inherent to collaboration and thus is not and cannot be ignored in collaborative planning discourse (for detailed discussion see Innes and Booher 2015).

Rydin conflates claims that come from practice and different actors. In contrast, we separate those claims and place them according to the three levels of analysis—context, actors, and practice.

We thank the anonymous reviewer for drawing our attention to this point.

References

Adams WM, Brockington D, Dyson J, Vira B (2003) Managing tragedies: understanding conflict over common pool resources. Science 302(5652):1915–1916

Albrechts L (2012) Reframing strategic spatial planning by using a coproduction perspective. Plan Theory 12(1):46–63

Allmendinger P, Haughton G (2012) Post-political spatial planning in England: a crisis of consensus? Trans Inst Br Geogr 37(1):89–103

Andersson P (2015) Scaffolding of task complexity awareness and its impact on actions and learning. ALAR J 21(1):124–147

Antonson H, Isaksson K, Storbjörk S, Hjerpe M (2016) Negotiating climate change responses: regional and local perspectives on transport and coastal zone planning in South Sweden. Land Use Policy 52:297–305

Ballard HL, Fernandez-Gimenez ME, Sturtevant VE (2008) Integration of local ecological knowledge and conventional science: a study of seven community-based forestry organizations in the USA. Ecol Soc 13(2). http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol13/iss2/art37/

Baxter J, Eyles J (1997) Evaluating qualitative research in social geography: establishing ‘rigour’ in interview analysis. Trans Inst Br Geogr 22(4):505–525

Beierle TC, Konisky DM (2000) Values, conflict, and trust in participatory environmental planning. J Policy Anal Manag 19(4):587–602

Berger-González M, Stauffacher M, Zinsstag J, Edwards P, Krütli P (2016) Transdisciplinary research on cancer-healing systems between biomedicine and the Maya of Guatemala: a tool for reciprocal reflexivity in a multi-epistemological setting. Qual Health Res 26(1):77–91

Bergmann M, Jahn T, Knobloch T, Krohn W, Pohl C, Schramm E (2012) Methods for transdisciplinary research: a primer for practice. Campus Verlag, Frankfurt

Berkes F (2009) Evolution of co-management: role of knowledge generation, bridging organizations and social learning. J Environ Manag 90(5):1692–1702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2008.12.001

Blackmore C (2007) What kinds of knowledge, knowing and learning are required for addressing resource dilemmas?: a theoretical overview. Environ Sci Policy 10(6):512–525

Blythe JN, Dadi U (2012) Knowledge integration as a method to develop capacity for evaluating technical information on biodiversity and ocean currents for integrated coastal management. Environ Sci Policy 19:49–58

Bohensky EL, Maru Y (2011) Indigenous knowledge, science, and resilience: what have we learned from a decade of international literature on “integration”. Ecol Soc 16(4):6

Bracken LJ, Bulkeley HA, Whitman G (2015) Transdisciplinary research: understanding the stakeholder perspective. J Environ Plan Manag 58(7):1291–1308

Brand R, Gaffikin F (2007) Collaborative planning in an uncollaborative world. Plan Theory 6(3):282–313

Brandt P, Ernst A, Gralla F, Luederitz C, Lang D, Newig J, Reinert F, Abson D, von Wehrden H (2013) A review of transdisciplinary research in sustainability science. Ecol Econ 92:1–15

Bremer S, Glavovic B (2013a) Mobilizing knowledge for coastal governance: re-framing the science–policy interface for integrated coastal management. Coast Manag 41(1):39–56

Bremer S, Glavovic B (2013b) Exploring the science–policy interface for Integrated Coastal Management in New Zealand. Ocean Coast Manag 84:107–118

Brown V, Harris J, Russell J (eds) (2010) Tackling wicked problems through the transdisciplinary imagination. Earthscan, London

Bruckmeier K (2005) Interdisciplinary conflict analysis and conflict mitigation in local resource management. AMBIO 34(2):65–73

Bruckmeier K, Höj Larsen C (2008) Swedish coastal fisheries—from conflict mitigation to participatory management. Mar Policy 32:201–211

Burger P, Kamber R (2003) Cognitive integration in transdisciplinary science: knowledge as a key notion. Issues Integr Stud 21:43–73

Butler JRA, Young JC, McMyn IAG, Leyshon B, Graham IM, Walker I, Baxter JM, Dodd J, Warburton C (2015) Evaluating adaptive co-management as conservation conflict resolution: learning from seals and salmon. J Environ Manag 160:212–225

Collins H, Evans R (2002) The third wave of science studies. Soc Stud Sci 32(2):235–296

Collins K, Blackmore C, Morris D, Watson D (2007) A systemic approach to managing multiple perspectives and stakeholding in water catchments: some findings from three UK case studies. Environ Sci Polic 10(6):564–574

Coppens T (2014) How to turn a planning conflict into a planning success? Conditions for constructive conflict management in the case of Ruggeveld-Boterlaar-Silsburg in Antwerp, Belgium. Plan Pract Res 29(1):96–111

Davoudi S (2015) Planning as practice of knowing. Plan Theory 14(3):316–331

Deepananda KA, Amarasinghe US, Jayasinghe-Mudalige UK (2015) Indigenous knowledge in the beach seine fisheries in Sri Lanka: an indispensable factor in community-based fisheries management. Mar Policy 57:69–77

Dickman AJ (2010) Complexities of conflict: the importance of considering social factors for effectively resolving human–wildlife conflict. Anim Conserv 13(5):458–466

Dietz T, Ostrom E, Stern PC (2003) The struggle to govern the commons. Science 302(5652):1907–1912

Domingo I, Beunen R (2013) Regional planning in the Catalan Pyrenees: strategies to deal with actors’ expectations, perceived uncertainties and conflicts. Eur Plan Stud 21(2):187–4313

Edelenbos J, van Buuren A, van Schie N (2011) Co-producing knowledge: joint knowledge production between experts, bureaucrats and stakeholders in Dutch water management projects. Environ Sci Policy 14:675–684

Emery SB, Perks MT, Bracken LJ (2013) Negotiating river restoration: the role of divergent reframing in environmental decision-making. Geoforum 47:167–177

Enengel B, Muhar A, Penker M, Freyer B, Drlik S, Ritter F (2012) Co-production of knowledge in transdisciplinary doctoral theses on landscape development—an analysis of actor roles and knowledge types in different research phases. Landsc Urban Plan 105(1–2):106–117

Ens EJ, Pert P, Clarke PA, Budden M, Clubb L, Doran B et al (2015) Indigenous biocultural knowledge in ecosystem science and management: review and insight from Australia. Biol Conserv 181:133–149

Fainstein SS (2000) New directions in planning theory. Urban Aff Rev 35(4):451–478

Flyvbjerg B, Richardson T (2002) Planning and Foucault. In search of the dark side of planning theory. In: Allmendinger IP, Tewdwr-Jones M (eds) Planning futures: new directions for planning theory. Routledge, London and New York, pp 44–63

Godemann J (2008) Knowledge integration: a key challenge for transdisciplinary cooperation. Environ Educ Res 14(6):625–641

Golobiĉ M, Maruŝiĉ I (2007) Developing an integrated approach for public participation: a case of land-use planning in Slovenia. Environ Plan B Plan Des 34(6):993–1010

Halla F (2005) Critical elements in sustaining participatory planning: Bagamoyo strategic urban development planning framework in Tanzania. Habitat Int 29(1):137–161

Harvey D (2008) The right to the city. New Left Rev 53:23–40

Healey P (1997) Collaborative planning: shaping places in fragmented societies. UBC Press, Vancouver

Healey P (2003) Collaborative planning in perspective. Plan Theory 2(2):101–123

Henle K, Alard D, Clitherow J, Cobb P, Firbank L, Kull T, McCracken D, Moritz RF, Niemelä J, Rebane M, Wascher D (2008) Identifying and managing the conflicts between agriculture and biodiversity conservation in Europe—a review. Agric Ecosyst Environ 124(1–2):60–71

Henry AD (2009) The challenge of learning for sustainability: a prolegomenon to theory. Hum Ecol Rev 16(2):131–140

Hoffmann S, Pohl C, Hering JG (2017) Methods and procedures of transdisciplinary knowledge integration: empirical insights from four thematic synthesis processes. Ecol Soc 22(1)

Innes JE, Booher D (2003) The impact of collaborative planning on governance capacity. Working Paper 2003/03, Institute of Urban and Regional Development, University of California, Berkeley

Innes J, Booher D (2010) Planning with complexity: an introduction to collaborative rationality for public policy. Routledge, London

Innes JE, Booher D (2015) A turning point for planning theory? Overcoming dividing discourses. Plan Theory 14(2):195–213

Jahn J, Keil F (2015) An actor-specific guideline for quality assurance in transdisciplinary research. Futures 65:195–208

Jahn T, Bergmann M, Keil F (2012) Transdisciplinarity. Between mainstreaming and marginalization. Ecol Econ 79:1–10

Jentoft S, Chuenpagdee R (2009) Fisheries and coastal governance as a wicked problem. Mar Policy 33(4):553–560. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2008.12.002

Jordan T (2014) Deliberative methods for complex issues: a typology of functions that may need scaffolding. Group Facil Res Appl J 13:50–71

Klenk N, Meehan K (2015) Climate change and transdisciplinary science: problematizing the integration imperative. Environ Sci Policy 54:160–167

Kombe WJ (2010) Land acquisition for public use, emerging conflicts and their socio-political implications. Int J Urban Sustain Dev 2(1–2):45–63

Lang DJ, Wiek A, Bergmann M, Stauffacher M, Martens P, Mol P, Swilling M, Thomas CJ (2012) Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science—practice, principles and challenges. Sustain Sci 7(1):25–43

Lebel L, Anderies JM, Campbell B, Folke C, Hatfield-Dodds S, Hughes TP, Wilson J (2006) Governance and the capacity to manage resilience in regional social-ecological systems. Ecol Soc 11(1):19

Madden F, McQuinn B (2014) Conservation’s blind spot: the case for conflict transformation in wildlife conservation. Biol Conserv 178:97–106

Margerum RD (2002) Collaborative planning: building consensus and building a distinct model for practice. J Plan Educ Res 21(3):237–253

Martín-Cantarino C (2010) Environmental conflicts and conflict management: some lessons from the WADI experience at El Hondo Nature Park (South-Eastern Spain). In: Scapini F, Ciampi G (eds) Coastal water bodies. Springer, Dordrecht, pp 61–77

McGuirk PM (2001) Situating communicative planning theory: context, power, and knowledge. Environ Plan A 33(2):195–217

Mistry J, Berardi A (2016) Bridging indigenous and scientific knowledge. Science 352(6291):1274–1275

Morton LW, Eigenbrode SD, Martin TA (2015) Architectures of adaptive integration in large collaborative projects. Ecol Soc 20(4)

Mostert E, Pahl-Wostl C, Rees Y, Searle B, Tàbara D, Tippett J (2007) Social learning in European river-basin management: barriers and fostering mechanisms from 10 river basins. Ecol Soc 12(1)

Mouffe C (2005) On the political. Routledge, New York

Munoz-Erickson (2014) Co-production of knowledge action systems in urban sustainable governance: the KASA approach. Environ Sci Policy 37:182–191

Muro M, Jeffrey P (2008) A critical review of the theory and application of social learning in participatory natural resource management processes. J Environ Plan Manag 51(3):325–344

Negev M, Teschner N (2013) Rethinking the relationship between technical and local knowledge: toward a multi-type approach. Environ Sci Policy 30:50–59

Nursey-Bray MJ, Vince J, Scott M, Haward M, O’Toole K, Smith T, Harvey N, Clarke B (2014) Science into policy? Discourse, coastal management and knowledge. Environ Sci Policy 38:107–119

Olsson P, Folke C, Berkes F (2004) Adaptive comanagement for building resilience in social–ecological systems. Environ Manag 34(1):75–90

Owens S, Cowell R (2011) Land and limits: interpreting sustainability in the planning process, 2nd edn. Routledge, London

Paavola J (2007) Institutions and environmental governance: a reconceptualization. Ecol Econ 63(1):93–103

Pahl-Wostl C (2007) Transitions towards adaptive management of water facing climate and global change. Water Resour Manag 21(1):49–62

Patterson ME, Montag JM, Williams DR (2003) The urbanization of wildlife management: social science, conflict, and decision making. Urban For Urban Green 1(3):171–183

Peltonen L, Sairinen R (2010) Integrating impact assessment and conflict management in urban planning: experiences from Finland. Environ Impact Assess Rev 30(5):328–337

Plummer R, Crona B, Armitage DR, Olsson P, Tengö M, Yudina O (2012) Adaptive comanagement: a systematic review and analysis. Ecol Soc 17(3):11

Plummer R, Baird J, Dzyundzyak A, Armitage D, Bodin Ö, Schultz L (2017) Is adaptive co-management delivering? Examining relationships between collaboration, learning and outcomes in UNESCO biosphere reserves. Ecol Econ 140:79–88

Pohl C (2011) What is progress in transdisciplinary research? Futures 43(6):618–626

Pohl C, Hirsch Hadorn G (2007) Principles for designing transdisciplinary research. Proposed by the Swiss Academies of Arts and Sciences. Oekom, Munich, p 124

Pohl C, Hirsch Hadorn G (2008) Methodological challenges of transdisciplinary research. Nat Sci Soc 16(2):111–121

Pohl C, Rist S, Zimmermann A, Fry P, Gurung GS, Schneider F, Speranza CI, Kiteme B, Boillat S, Serrano E, Hirsch Hadorn G, Wiesmann U (2010) Researchers roles in knowledge co-production: experience from sustainability research in Kenya, Switzerland, Bolivia and Nepal. Sci Public Policy 37(4):267–281

Polk M (2014) Achieving the promise of transdisciplinarity: a critical exploration of the relationship between transdisciplinary research and societal problem solving. Sustain Sci 9(4):439–451

Polk M (2015a) Transdisciplinary co-production: designing and testing a transdisciplinary research framework for societal problem solving. Futures 65:110–122

Polk M (ed) (2015b) Co-producing knowledge for sustainable cities: joining forces for change. Routledge, London

ProClim (1997) Research on sustainability and global change—visions in science policy by Swiss researchers. CASS/SANW, Bern. http://www.proclim.ch/Reports/Visions97/Visions_E.html. Accessed 3 Dec 2006

Putnam LL, Burgess G, Royer R (2003) We can’t go on like this: frame changes in intractable conflicts. Environ Pract 5(3):247–255

Raco M, Lin WI (2012) Urban sustainability, conflict management, and the geographies of postpoliticism: a case study of Taipei. Environ Plan C Govern Policy 30(2):191–208

Ratner BD, Meinzen-Dick R, May C, Haglund E (2013) Resource conflict, collective action, and resilience: an analytical framework. Int J Commons 7(1):183–208

Raymond CM, Fazey I, Reed MS, Stinger LC, Robinson GM, Evely AC (2010) Integrating local and scientific knowledge for environmental management. J Environ Manag 91:1766–1777

Redpath SM, Arroyo BE, Leckie FM, Bacon P, Bayfield N, Gutierrez RJ, Thirgood SJ (2004) Using decision modeling with stakeholders to reduce human–wildlife conflict: a raptor–grouse case study. Conserv Biol 18(2):350–359

Redpath SM, Young J, Evely A, Adams WM, Sutherland WJ, Whitehouse A, Amar A, Lambert RA, Linnell JDC, Watt A, Gutierrez RJ (2013) Understanding and managing conservation conflicts. Trends Ecol Evol 28(2):100–109

Reed M, Evely AC, Cundill G, Fazey I, Glass J, Laing A, Nevig J, Parrish B, Prell C, Raymond C, Stringer L (2010) What is social learning? Ecol Soc 15(4). http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol15/iss4/resp1/

Reed MS, Buenemann M, Atlhopheng J, Akhtar-Schuster M, Bachmann F, Bastin G, Bigas H, Chanda R, Dougill J, Essahli W, Evely C, Fleskens L, Geeson N, Glass J, Hessel R, Holden J, Ioris AAR, Kruger B, Liniger P, Mphinyane W, Nainggolan D, Perkins J, Raymond M, Ritsema J, Schwilch G, Sebego R, Seely M, Stringer C, Thomas R, Twomlow S, Verzandvoort S (2011) Cross-scale monitoring and assessment of land degradation and sustainable land management: a methodological framework for knowledge management. Land Degrad Dev 22(2):261–271

Ross D (2009) The use of partnering as a conflict prevention method in large-scale urban projects in Canada. Int J Manag Proj Bus 2(3):401–418

Rydin Y (2007) Re-examining the role of knowledge within planning theory. Plan Theory 6:52–68

Sandercock L (2003) Out of the closet: the importance of stories and storytelling in planning practice. Plan Theory Pract 4(1):11–28

Schauppenlehner-Kloyber E, Penker M (2015) Managing group processes in transdisciplinary future studies: how to facilitate social learning and capacity building for self-organised action towards sustainable urban development? Futures 65:57–71

Schmidt L, Neuburger M (2017) Trapped between privileges and precariousness: tracing transdisciplinary research in a postcolonial setting. Futures 93:54–67

Scholz RW, Steiner G (2015a) The real type and ideal type of transdisciplinary processes: part I—theoretical foundations. Futures 10:527–544

Scholz RW, Steiner G (2015b) The real type and ideal type of transdisciplinary processes: part II—what constraints and obstacle do we meet in practice? Futures 10:653–671

Schusler TM, Decker DJ, Pfeffer MJ (2003) Social learning for collaborative natural resource management. Soc Nat Resour 16(4):309–326

SDGs, UN (2015) General Assembly Resolution A/RES/70/1. Transforming Our World, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available from: http://www.un.org/ga/search/view_doc.asp?symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E

Shmueli DF (2008) Framing in geographical analysis of environmental conflicts: theory, methodology and three case studies. Geoforum 39(6):2048–2061

Spangenberg JH (2011) Sustainability science: a review, an analysis and some empirical lessons. Environ Conserv 38(3):275–287

Stepanova O (2013) Knowledge integration in the management of coastal conflicts in urban areas: two cases from Sweden. J Environ Plan Manag 57(11):1658–1682

Stepanova O (2015) Conflict resolution in coastal resource management: comparative analysis of case studies from four European countries. Ocean Coast Manag 103:109–122

Stepanova O, Bruckmeier K (2013) The relevance of environmental conflict research for coastal management. A review of concepts, approaches and methods with a focus on Europe. Ocean Coast Manag 75:20–32

Stringer LC, Dougill AJ, Fraser E, Hubacek K, Prell C, Reed MS (2006) Unpacking “participation” in the adaptive management of social–ecological systems: a critical review. Ecol Soc 11(2)

Sun L, Yung EHK, Chan EHW, Zhu D (2016) Issues of NIMBY conflict management from the perspective of stakeholders: a case study in Shanghai. Habitat Int 53:133–141

Sze MNM, Sovacool BK (2013) Of fast lanes, flora, and foreign workers: managing land use conflicts in Singapore. Land Use Policy 30(1):167–176

Talwar S, Wiek A, Robinsons J (2011) User engagement in sustainability research. Sci Public Policy 38:379–390

Tengö M, Brondizio ES, Elmqvist T, Malmer P, Spierenburg M (2014) Connecting diverse knowledge systems for enhanced ecosystem governance: the multiple evidence base approach. AMBIO 43(5):579–591

Tengö M, Hill R, Malmer P, Raymond CM, Spierenburg M, Danielsen F et al (2017) Weaving knowledge systems in IPBES, CBD and beyond—lessons learned for sustainability. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 26:17–25

Von Der Dunk A, Grêt-Regamey A, Dalang T, Hersperger AM (2011) Defining a typology of peri-urban land-use conflicts—a case study from Switzerland. Landsc Urban Plan 101(2):149–156

Walter AI, Helgenberger S, Wiek A, Scholz RW (2007) Measuring societal effects of transdisciplinary research projects—design and application of an evaluation method. Eval Program Plan 30(4):325–338

Watson V (2014) Co-production and collaboration in planning—the difference. Plan Theory Pract 15(1):62–76

Westberg L, Polk M (2016) The role of learning in transdisciplinary research: moving from a normative concept to an analytical tool through a practice-based approach. Sustain Sci 11(3):385–397

Wickson F, Carew A, Russell AW (2006) Transdisciplinary research: characteristics, quandaries and quality. Futures 38(9):1046–1059