Abstract

This paper explores the current role of mindfulness in sustainability science, practice, and teaching. Based on a qualitative literature review that is complemented by an experimental learning lab, we sketch the patterns and core conceptual trajectories of the mindfulness–sustainability relationship. In addition, we assess this relationship within the field of climate change adaptation and risk reduction. The results highlight that notions such as ‘sustainability from within’, ‘ecological mindfulness’, ‘organizational mindfulness’, and ‘contemplative practices’ have been neglected in sustainability science and teaching. Whilst little sustainability research addresses mindfulness, there is scientific support for its positive influence on: (1) subjective well-being; (2) the activation of (intrinsic/ non-materialistic) core values; (3) consumption and sustainable behavior; (4) the human–nature connection; (5) equity issues; (6) social activism; and (7) deliberate, flexible, and adaptive responses to climate change. Most research relates to post-disaster risk reduction, although it is limited to the analysis of mindfulness-related interventions on psychological resilience. Broader analyses and foci are missing. In contrast, mindfulness is gaining widespread recognition in practice (e.g., by the United Nations, governmental and non-governmental organizations). It is concluded that mindfulness can contribute to understanding and facilitating sustainability, not only at the individual level, but sustainability at all scales, and should, thus, become a core concept in sustainability science, practice, and teaching. More research that acknowledges positive emotional connections, spirituality, and mindfulness in particular is called for, acknowledging that (1) the micro and macro are mirrored and interrelated, and (2) non-material causation is part of sustainability. This paper provides the first comprehensive framework for contemplative scientific inquiry, practice, and education in sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Humanity is facing increasingly complex environmental and sustainability challenges (Kates et al. 2001; Sol and Wals 2015). They are a manifestation of what sustainability scientists describe as a “systemic world” characterized by multiple causations, interactions, complex feedback loops, and inevitable uncertainty and unpredictability (Lang et al. 2012). Issues such as climate change, disasters, energy, food, waste and water management, land use change, and biodiversity loss are highly complex and require an urgent response (Jerneck et al. 2011; Wals and Corocoran 2012).

Current coordination mechanisms, problem-solving strategies, and modes of scientific inquiry, teaching, and learning appear insufficient to address global sustainability challenges (Sol and Wals 2015). As a result, expanded consciousness, embodied in notions such as mindfulness, compassion and empathy, is emerging as a potential new area of exploration to address these challenges (Edwards 2015; Goleman 2011). Increasing research into mindfulness supports related advancements.

In fact, progress in neuroscience and neuroplasticity, described in both the scientific and popular literature, suggests that mindfulness can literally rewire our brains (Doty 2016; Hölzel et al. 2011; Lazar et al. 2005; Luders et al. 2009; Powietrzynska et al. 2015; Tang et al. 2012; Vestergaard-Poulsen et al. 2009), and may be a necessary component of the conversion to a more sustainable society (Koger 2015). Mindfulness is generally understood as intentional, compassionate, and non-judgmental attentiveness to the present moment (Baer 2003; Condon et al. 2013; Kabat-Zinn 1990), which is associated with greater emotional intelligence (Schutte and Malouff 2011).Footnote 1 It is an inherent capacity of the human organism that is rooted in the fundamental activities of consciousness and linked to established theories of attention and awarenessFootnote 2 (Buss 1980). Its study is part of a longstanding field that recognizes the value of increased consciousness brought to bear on subjective experience, behavior, and the immediate environment (Amel et al. 2009; Brown et al. 2007; Carver and Scheier 1981; Csikszentmihalyi 1997; Duval and Wicklund 1972; Jacob et al. 2009).

As a strategy, mindfulness is increasingly used in various professional fields and disciplines ranging from health care and the performing arts to pedagogy and business (Black 2010; Boyce 2011). However, further research is needed to better understand the scope of such applications (Brown et al. 2007; Eriksen and Ditrich 2015). The question thus arises of whether the concept of mindfulness also applies to the sustainability field, at a time of rapid globalization, permanent change, and increasing risk.

Against this background, this paper assesses the current role of mindfulness in sustainability research, practice, and teaching.Footnote 3 Using an extensive literature review complemented by an experimental learning lab (described in “Methodology”), we outline the core conceptual trajectories of mindfulness in general sustainability research, practice, and teaching (Sects. “Mindfulness in general sustainability research”, “Mindfulness in general sustainability practice”, “Mindfulness in general sustainability teaching”). We also assess it more specifically in relation to the field of climate change adaptationFootnote 4 and risk reduction (Sects. “Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction research”, “Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction practice”, “Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction teaching”). Finally, we discuss its potential role in sustainability science, providing a comprehensive framework for systematizing and analyzing related interlinkages, and highlighting related implications (theoretical, methodological, etc.).

Methodology

The approach consisted of a literature review, which was complemented by an experimental learning lab on mindfulness in sustainability science, practice, teaching, and learning. The literature review included both grey literature and scientific papers (identified via Scopus, Web of Science, LUBsearch, and Google Scholar) that connected mindfulness and sustainability both explicitly and implicitly. To conduct a comprehensive review of relevant research across multiple disciplines, the search string included the following terms: (mindfulness OR mindful* OR contemplative OR compassion OR meditat*) AND (sustainability OR sustainable) AND/OR (“climate change adaptation” OR (adaptation AND climate) OR “risk reduction” OR “disaster response” OR “disaster recovery” OR “hazard mitigation” OR names of specific hazards, such as flood OR storm OR landslide OR earthquake). After screening the abstracts, irrelevant studies (i.e. false positives) were removed, while other significant studies were identified using snowball sampling of the references.Footnote 5

Development of the experimental learning lab began in 2015. In 2016, it ran for 3 months and included 70 students from two sustainability-focused Masters’ Programs.Footnote 6 The lab was incorporated into a course on sustainable planning, climate change adaptation, and risk reduction. Contemplative teaching and learning practices were integrated into required everyday course activities (reflecting, listening, debating, working together, etc.; “Appendix 1”). In addition, written assignments on sustainability and mindfulness were offered as graded tasks, and a total of 16 voluntary mindfulness sessions (“Appendix 2”) were conducted outside the usual course activities (i.e., lectures, seminars, group work, and field trips). The mindfulness sessions were implemented in coordination with the Students’ Health Centre, and related information was provided in the course schedule, the students’ course portal, and a closed Facebook group. The sessions lasted between 15 and 30 min and included a variety of techniques (“Appendix 2”). Written and oral course evaluations (response rates: 50/100%), and two surveys and a group discussion (response rates: 71/23/29%), were conducted to assess participants’ understanding and knowledge of mindfulness and sustainability, and the impacts of their mindfulness practices on learningFootnote 7 (“Appendix 3”–“Appendix 6”). The first survey was conducted before the lab was implemented, while the second survey and the group discussion took place afterwards (“Appendix 3” and “Appendix 6”). The successful implementation of the experimental learning lab resulted in the development of a new Master’s level course on sustainability, inner transition, and mindfulness in 2016.Footnote 8

The analysis of the data (literature and lab) involved: (1) the identification of patterns and core conceptual trajectories in current sustainability research, practice, and teaching, (2) a comparison of the review outcomes with the results of the experimental learning lab,Footnote 9 and (3) a comparison of the identified patterns/ trajectories between the three areas (i.e. research, practice, and teaching) and an assessment of related implications (e.g. ontology, methodology, synergies, and research gaps). Literal reading and qualitative coding were used to analyze and triangulate the results (Glaser and Strauss 1967; Strauss and Corbin 1998).Footnote 10

Mindfulness and sustainability in research

This section presents the results of the general analysis of mindfulness and sustainability in research (Sect. “Mindfulness in general sustainability research”). Then, the mindfulness–sustainability relationship is analyzed in the specific context of sustainable climate change adaptation and risk reduction (Sect. “Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction research”).

Mindfulness in general sustainability research

The analysis identified three patterns (core conceptual trajectories) in mindfulness and sustainability research, namely:

-

There is a blind spot in the academic debate on mindfulness in sustainability research.

-

Research on mindfulness is increasing, which (implicitly) provides growing evidence of its positive effects and potential contributions to sustainability/ sustainability science.

-

Only a few initial attempts have been made to examine mindfulness–sustainability linkages more explicitly.

On one hand, the literature review revealed that mindfulness is generally not addressed in sustainability research. Analyses focus on objective interactions between natural, social, and human systems, whilst subjective aspects of human beings tend to be ignored (Sumi 2007). The exceptions that were identified linked mindfulness to the human–nature connection and native ways of knowing (e.g., Anthony 2013; Lockhart 2011), social justice and social activism (e.g., Brown et al. 2007; Doetsch-Kidder 2012; Jacob et al. 2009), and more recently to sustainability-oriented innovations (Siqueira and Pitassi 2016; Lengyel 2015). This result was confirmed by the findings from the experimental learning lab. A total of 83% of participants said that they had not come across the issue of mindfulness in their environmental studies and sustainability science reading. In addition, only four respondents made links between mindfulness and nature/ the environment.

The fact that subjective human aspects tend to be ignored in sustainability research was confirmed in extensive reviews by Kjell (2011) and Kajikawa (2008), who independently found that sustainability and well-being research are two separate fields. Other scholars, such as Rinne et al. (2013) and Fabbrizzi et al. (2016), have also highlighted the lack of research at the intersection of societal sustainability and individual well-being. This gap can be illustrated by research into sustainable consumption and behavior. Kajikawa (2008) shows that studies on the topic generally focus on the impact of people’s consumption on sustainability, rather than the impact of aspects that lead to unsustainable consumption, such as lifestyles, well-being, or mindfulness (cf. Rogerson and Kim 2005).

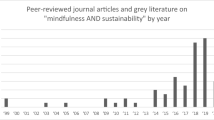

On the other hand, mindfulness research is rapidly growing (AMRA 2016) and is making an increasing contribution to sustainability. Since 2009, there has been a 30% annual increase in the frequency of references to mindfulness in peer-reviewed science-, art-, and humanities-based articles (Ericson et al. 2014). The momentum is coming from fields such as psychology and medicine, which until recently have received minimal attention from sustainability practitioners and academics (Jones 2015). Such work focuses on a range of well-being and health-related conditions (psychological and physical) (Brown et al. 2007; Ericson et al. 2014; Davidson et al. 2003) and the activation of (intrinsic/ non-materialistic) core values (Sheth et al. 2010).

Although research into mindfulness and related attributes has not explicitly addressed the relationship between mindfulness and sustainability (Ericson et al. 2014), it has highlighted the complex linkages with sustainable development, from the individual to the global level (Brown et al. 2007). Derived from the principle of dependent origination, it recognizes that all beings are deeply connected to other beings and the world, including their actions and thinking (Yeh 2006).Footnote 11 It recognizes the adaptive value of bringing consciousness to bear not only on subjective experience, but also on behavior and the environment (Amel et al. 2009; Brown et al. 2007; Carver and Scheier 1981; Csikszentmihalyi 1997; Duval and Wicklund 1972; Jacob et al. 2009).

In 2015, the notion of “ecological mindfulness” was put forward by sustainability scholars as a new approach to promote social and environmental sustainability (Mueller and Greenwood 2015; Sol and Wals 2015). This notion is based on research which suggests that mindfulness is associated with ecologically-responsible behavior that is oriented to the common good (Brown and Kasser 2005),Footnote 12 although the specifics are culturally shaped (Chinn 2015). Ecological mindfulness also promotes the integration and blending of thought, rather than disintegration and separation (Mueller and Greenwood 2015). It can thus also be seen as an initial attempt to link the concepts of mindfulness and sustainability, as it lies at the intersection of ontological hybridity and can be seen as a way to approach the study of the world, or as a way to distance us from “either/ or” thinking, and move towards “not-only-but-also” thinking (Mueller and Greenwood 2015; Chadwick 2013). See also “Mindfulness in general sustainability practice” and “Mindfulness in general sustainability teaching”.

Whilst the literature review highlights that research on mindfulness and sustainability is scarce and fragmented, it provides scientific support for the positive influence of mindfulness on: (1) subjective well-being (e.g., Brown et al. 2007; Jacob et al. 2009; Khoury et al. 2013); (2) activation of (intrinsic/ non-materialistic) core values (e.g., Brown et al. 2007; Carmody et al. 2009; Brown and Kasser 2005; Shapiro et al. 2006; Sheth et al. 2010); (3) consumption and sustainable behavior (e.g., Amel et al. 2009; Brown and Kasser 2005; Brown and Ryan 2003; Brown et al. 2007, 2004; Ericson et al. 2014; Goleman 2009; Jacob et al. 2009; Sheth et al. 2010); (4) the human–nature connection (e.g., Amel et al. 2009; Anthony 2013; Howell et al. 2011; Lockhart 2011); (5) equity issues (e.g., Brown et al. 2007; Harris and Bordere 2016; Shah et al. 2012); and (6) social activism (e.g., Brown et al. 2007; Doetsch-Kidder 2012).Footnote 13 Whilst these aspects are highly interlinkedFootnote 14 and clearly relate to wider (socio-political power) structures, mindfulness research tends to focus on the individual level.

Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction research

The analysis identified the following core conceptual trajectories in research that addresses mindfulness and sustainability in relation to climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction:

-

There is a blind spot in the academic debate on mindfulness in anticipatory adaptation and risk reduction research.

-

In the context of climate change and climate change mitigation, more studies can be found that link individuals’ state of being to sustainability.

-

There is an increasing body of research on mindfulness in post-disaster response and recovery as a way to increase psychological resilience (with links to response and recovery preparedness).

-

The concept of “organizational mindfulness” that was developed in the domain of risk and safety research has recently been applied to sustainability.

The literature review identified a blind spot in the academic debate on mindfulness in anticipatory adaptation and risk reduction research. This is supported by Ryan (2016) who states that there is a little research into the potential of enhanced emotional knowledge and well-being to prompt anticipatory adaptation.Footnote 15 Here, “anticipatory” relates to the pro-active integration of adaptation and risk reduction in the pre-disaster context (development work), rather than the integration of such considerations in the post-disaster response (emergency assistance) or recovery (assistance for rehabilitation and reconstruction) (IPCC 2001, 2014). The results were confirmed by the findings from the experimental learning lab. A total of 83% of participants said that they had not come across the issue of mindfulness in the risk reduction and climate change adaptation literature.

In contrast, in the context of climate change and climate change mitigation, there are a growing number of studies that link individuals’ state of being to sustainability. In particular, the influence of emotional knowledge on how people experience and understand climate change is receiving increasing attention (Doherty and Clayton 2011; Koger 2015). However, only few studies have explored the influence of emotions, a powerful motivator for human behavior, on how individuals process and react to climate change information (Lu and Schuldt 2016). Exceptions are Ryan (2016) and Lu and Schuldt (2016). The latter explore how compassion influences individuals’ support for government actions to address climate change. They demonstrate that the influence of compassion extends beyond increasing the motivation to act in ways that alleviate immediate suffering, highlighting the overlooked role of mindfulness in contributing to citizens’ policy support regarding climate change mitigation.

Most of the identified studies that link mindfulness with climate change adaptation and/or risk reduction have examined mindfulness in the context of post-disaster response and recovery (with links to response and recovery preparedness). Doherty and Clayton (2011) confirm this result and also highlight the need to apply a better understanding of mindfulness in relation to disasters to the context of climate change. Nevertheless, current work mainly assesses the potential of specific mindfulness-related strategies and interventions for increasing psychological resilience in particular target groups, rather than individual mindfulness in general (i.e., mindfulness disposition) (Thompson et al. 2011). These interventions include meditation or relaxation techniques aimed at different groups, including children and young people affected by disasters (Catani et al. 2009; Zeller et al. 2015), disaster survivors and at-risk individuals (Hechanova et al. 2015; Hoeberichts 2012; Matanle 2011; Srivatsa et al. 2013; Yoshimura et al. 2015), disaster aid workers (Eriksen and Ditrich 2015; Hoeberichts 2012; Smith et al. 2011; Waelde et al. 2008), and disaster researchers (Eriksen and Ditrich 2015). The studies have advanced knowledge in relation to trauma/ traumatic stress reduction (see Thompson et al. [2011] for a review of related advancements). To date, cultural differences with respect to mindfulness and mindfulness interventions have barely been addressed (cf. Chinn 2015).

Recently, the notion of “organizational mindfulness” has emerged. The concept was developed in the domain of risk and safety research, and has only recently been extended to sustainability, and sustainable risk reduction in particular (Aviles and Dent 2015; Becke 2014; Becke et al. 2012; Senghaas-Knobloch 2014). Weick and Sutcliffe (2007) based their conceptualization of organizational mindfulness on high-reliability organizations (i.e. organizations that must find effective ways of dealing with potential catastrophes resulting from the inherently complex and dangerous nature of their work [cf. Sutcliffe 2011]).Footnote 16 The concept highlights collective and organizational learning with respect to the anticipation of, and coping with, unexpected risky events that are found in volatile and unpredictable environments, and are harmful to the viability of organizations (Becke et al. 2012; Becke 2014). In addition, organizational mindfulness refers to the idea that actively nurturing and developing social resources is key to organizations’ longevity and sustainability, and especially critical for organizations facing extreme events with potentially long-lasting consequences (Becke 2014).

Overall, the literature review highlights that the field is still emerging. In addition to aspects related to sustainability in general, studies particularly highlight and provide scientific support for the positive influence of mindfulness on: (1) minimizing automatic, habitual, or impulsive reactions; (2) facilitating more flexible, adaptive responses to events (e.g., Brown et al. 2007; Hechanova et al. 2015; Waelde et al. 2008); and (3) influencing individuals’ support for planned actions to address climate change (all of which are relevant to the anticipation of, and coping with, unpredictability in organizations [i.e., “organizational mindfulness”]). Here, ‘planned’ adaptation is the result of a deliberate (governmental) policy decision, based on an awareness that conditions have changed—or are about to change—and that action is required to return to, maintain, or achieve a desired state (IPCC 2001, 2014).

Mindfulness and sustainability in practice

This section presents the results of the analysis of mindfulness and sustainability practice in general (Secti “Mindfulness in general sustainability practice”). It is then analyzed in the specific context of climate change adaptation and risk reduction (Secti “Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction practice”).

Mindfulness in general sustainability practice

The literature review revealed the following core conceptual trajectories:

-

Mindfulness-based responses to environmental challenges are being increasingly promoted.

-

Notions such as the “mindfulness revolution”, “contemplative environmental practice”, “contemplative practice for sustainability”, and “ecological mindfulness” have emerged.

In practice, mindfulness-based responses to environmental challenges are increasingly promoted by development organizations, networks, and coalitions; sometimes termed the “mindfulness revolution”. This refers to the rapid emergence of initiatives and literature that aim to revolutionize current sustainability practice (Boyce 2011; Edwards 2015; Koger 2015). This result is in line with the outcomes of the experimental learning lab, where participants who had come across mindfulness in their readings referred to the practice-related approaches found in green movements.

Mindfulness-based responses to environmental challenges are promoted by both secular and faith-based organizations, and provide support for individuals and institutions (Edwards 2015; Koger 2015).Footnote 17 They encourage mindful awareness of underlying emotions, thoughts, values, and experiences that contribute to (un)sustainable actions, in turn, leading to increased social activism and justice (Hanh and Weisman 2008; Kaza 2008).Footnote 18

In this context, notions such as “contemplative environmental practice”, “contemplative practice for sustainability”, and “ecological mindfulness” have emerged (cf. Sects. “Mindfulness in general sustainability research” and “Mindfulness in general sustainability teaching”). They are increasingly promoted by all kinds of organizations, including private businesses, non-profit, and faith-based organizations (AASHE 2016; Sangha 2016b; Unlimited 2015). Although implicit, applications often relate to the issue of climate change mitigation (cf. Sect. “Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction practice”). An example is the Whidbey Institute, which, in cooperation with the Washington Centre, organized a conference in 2014 on the issue of “sustainability and contemplative practice” (see also “Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction practice” and “Mindfulness and sustainability in teaching”). Other potential areas of application include the eco-tourism sector (Lengyel 2015).

Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction practice

The analysis identified the following core conceptual trajectories with respect to mindfulness in relation to climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction practice:

-

Many faith-based organizations recognize the need to respond to climate change and provide mindful-based direction for that response.

-

There is also an increase in secular initiatives that promote mindfulness-based methods to respond to climate change.

-

Most mindfulness-related practice relates to climate change mitigation, rather than climate change adaptation.

-

Exceptions relate mostly to the promotion of mindfulness-based response and recovery by different emergency organizations, including preparedness.

Many faith-based organizations, including leading Buddhist and Christian groups (e.g., the Vatican), are recognizing the need to respond to climate change, and are asked to provide mindful-based direction to entities such as the United Nations, governmental and non-governmental institutions (Koger 2015).Footnote 19 In 2014, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) requested, for instance, the Buddhist leader Thich Nhat Hanh to provide a statement on climate change. This was subsequently published on the UNFCCC website ahead of the Paris Climate Summit in September 2015 (Hanh 2015). Hence, the faith community is also playing an increasingly important role in holding governments accountable for mindfully responding to climate change and addressing climate justice (Koger 2015; Sangha 2016a). Influential groups include GreenFaith (led by Christians and Jews) and the (Buddhist) One Earth Sangha, which published a series of online conversations on “Mindfulness and Climate Action”, and the Dharma Teachers Statement on Climate Change (Dharma Teachers International 2014). Other bodies include the Convergence Community, a global network of religious–environmental leaders, and the Our Voices coalition that was specifically created to bring faith to the Paris Summit. Joint efforts by these actors resulted in an Interfaith Statement on Climate Change that was published in response to the Paris Agreement.Footnote 20 Notably, the faith community is also an important driver of public opinion and mindful actions taken in response to climate change. A recent study has, for instance, demonstrated the so-called “Francis effect”, i.e., the positive effect that Pope Francis and his encyclical “Laudato Si: On Care for Our Common Home” has had on people’s perceptions and responses to climate change (Maibach et al. 2015) (see footnote 17).

In addition, there are an increasing number of secular initiatives that promote mindfulness-based methods to support both individuals (including sustainability and environmental professionals) and organizations in promoting the transition to a more climate-resilient society (Koger 2015). However, most of these initiatives relate to climate change mitigation, i.e., the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. In this context, the term “mindful climate action” was coined.Footnote 21 Examples are “Active Hope” as well as the “Work that Reconnects Network” and other initiatives based on deep ecology pioneer Joanna Macy’s perspective on ecological activism (Macy and Young Brown 1998; Vaughan-Lee 2013).

In contrast, there is less evidence of mindfulness-related practice in the fields of climate change adaptation and risk reduction, and there is hardly any evidence of mindfulness-related practice that is explicitly focused on anticipatory adaptation and risk reduction.

However, consistent with existing research (cf. Sect. “Mindfulness and sustainability in research”), mindfulness-based approaches to disaster response and recovery are increasingly promoted, especially by emergency organizations. One example is the Red Cross, who developed an “After the emergency” podcast for young people affected by the 2009 Victorian bushfires. The podcast provides information about trauma, how to cope with the stress of an emergency, and how to increase psychological resilience in the long term (Australian Red Cross 2015).

These results contrast with the outcomes from the experimental learning lab. Whilst a total of 79% of respondents felt that mindfulness had an influence on their daily life in terms of sustainable behavior, 32% thought that it was irrelevant to sustainability practice, in general, and adaptation and risk reduction in particular.

Mindfulness and sustainability in teaching

This section presents the results of the analysis of mindfulness in sustainability teaching, in general (Sect. “Mindfulness in general sustainability teaching”). It is then analyzed in the context of teaching sustainable climate change adaptation and risk reduction (Sect. “Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction teaching”).

Mindfulness in general sustainability teaching

The analysis revealed the following core conceptual trajectories:

-

Compared to pedagogy in general, mindfulness has received little attention in sustainability teaching and learning.

-

Contemplative methods have only recently been explicitly promoted as a new way of teaching and learning that is needed to create a more sustainable society.

-

In line with this, the notion of “ecological mindfulness” has emerged to promote a different way of learning and foster scientific understanding and action.

-

Recently scholars have argued for the need for mindfulness in improving sustainability institutions and curricula.

Mindfulness is increasingly recognized and used in pedagogy (Black 2010; Schoeberlein 2009; Schonert-Reichl and Roeser 2016). Despite an increasingly fragmented educational discourse in general (Mueller and Greenwood 2015; Sameshima and Greenwood 2015), it is receiving mainstream acceptance as a way to enhance both students’ and teachers’ well-being (e.g., Albrecht et al. 2012; Black et al. 2009; Greenberg and Harris 2012; Mendelson et al. 2010). Its success is based on a wealth of research that supports the benefits of mindfulness for memory, learning, emotional regulation, and well-being, together with its importance for interpersonal and emotional aspects of pedagogy and the teaching environment (e.g., Biggs and Tang 2011; Hülsheger et al. 2013; Illeris 2009; IMS 2015; Lee 2012; Meiklejohn et al. 2012; Wisner 2014). The results from the experimental learning lab indicated that 60% of survey participants felt that mindfulness was relevant for sustainability teaching and learning (pre-lab survey), which increased to 79% after the lab ended. In addition, those who had participated in the voluntary mindfulness sessions agreed that it had a positive influence on their learning.

In recent years, scholars have turned their attention to defining theoretical models for mindful teaching, and their translation into pedagogical practice (e.g., Albrecht et al. 2012; Ragoonaden 2015; Weaver and Wilding 2013).Footnote 22 Mindful teaching is seen as an approach that integrates the following aspects: (1) the building of a “community” or connection (teacher–student and student–student) based on compassion, non-judgmental, and accepting openness, and the establishment of respectful boundaries; and (2) the creation of an engaging and reflective learning environment, which supports self-observation and mutual learning, whilst acknowledging differences in cultural backgrounds, experiences, social behavior, and learning (Wamsler 2015/2016).

While mindfulness is playing an increasing role in pedagogy, in general, it has received limited attention in the context of sustainability teaching and learning. It is only recently that contemplative teaching methods have explicitly been promoted as a new way to address socio-ecological challenges and create a more just, compassionate, reflective, and sustainable society (ACMHE 2016; Gugerli-Dolder and Frischknecht-Tobler 2011; Gugerli-Dolder et al. 2013; Litfin and Abigail 2014; Schoeberlein 2009). This is seen in the recent increase in organizations and institutions that offer workshops, seminars, professional networks, and training on the subject.Footnote 23

As in general sustainability research and practice (Sects. “Mindfulness in general sustainability research” and “Mindfulness in general sustainability practice”), “ecological mindfulness” is emerging in sustainability teaching (Mueller and Greenwood 2015; Sol and Wals 2015). Underlying this notion is the idea that the proliferation of “adjectival education”Footnote 24 (including sustainability education) is inconsistent with the interdisciplinary and cross-hybrid learning needed to foster scientific and cultural understanding and actions leading to socio-ecological change. Hence, ecological mindfulness suggests that the integration and blending of thought, rather than its disintegration and separation, should be the purpose of sustainability teaching and learning (Mueller and Greenwood 2015; cf. Sects. “Mindfulness in general sustainability research” and “Mindfulness in general sustainability practice”). Furthermore, scholars argue that the ecological mindfulness of teachers is crucial in shaping students’ understanding of nature–society relations, and that it requires integrating indigenous cultural knowledge and sustainable practices within existing scientific frameworks (Chinn 2015).

In addition, scholars have recently argued for the need for mindfulness approaches to improve educational bodies and curricula oriented towards sustainability and well-being (e.g., linked to the notion “ecological learning”). It is argued that in the context of sustainability, teaching and learning require spaces where diverse ecological, holistic, and place-responsive perspectives can take root, be nurtured, and flourish into ways of knowing, being, and becoming that serve people, places, and the planet (Greenwood 2013; Gugerli-Dolder and Frischknecht-Tobler 2011; Sameshima and Greenwood 2015). In addition, teaching should become a way to work towards a “learning system”, in which people collectively become more capable of withstanding setbacks and dealing with insecurity, complexity and risks, in which mindfulness can play a role (Sol and Wals 2015).

Mindfulness in climate change, adaptation, and risk reduction teaching

The analysis revealed the following core conceptual trajectories:

-

Contemplative teaching and learning methods are being explored in the context of sustainability education, notably to address new demands caused by climate change (i.e., individual capacities and qualities).

-

In contrast, there is a little academic discourse on contemplative methods for climate change adaptation and risk reduction education.

-

There is, however, an increase in neuroscience-based mental health and mindfulness training provided by private institutions to help people to cope with climate-enhanced adversities.

In light of the growing risk and uncertainties, sustainability is increasingly being referred to as a learning challenge. It is argued that in addition to appropriate forms of governance, legislation, and regulation, alternative forms of education and learning are needed for people to develop capacities and qualities that allow them to contribute to alternative (climate adapted) behaviors, lifestyles and systems, both individually and collectively (Sol and Wals 2015).

Consequently, contemplative teaching and learning methods are being explored in sustainability education, particularly regarding courses that address climate change issues. Examples are the revision and development of new syllabuses on global environmental politics, sustainability leadership development and “mindful climate action” (Barret et al. 2016; Litfin and Abigail 2014).Footnote 25 In line with this, 79% of the survey participants in the experimental learning lab felt that mindfulness was relevant to sustainability teaching and learning, including issues of climate change adaptation and risk reduction, while those who had participated in the mindfulness sessions agreed that they had had a positive influence on related learning. Overall, around 80% welcomed the integration of mindfulness into the course, and 20% were neutral (based on the pre-lab survey and oral course evaluation). Around 64% stated that the lab added extra value to the course in general. Only 1 out of 70 students said that its continuation would not be worthwhile (oral course evaluation).

However, there is a little academic discourse on the subject of contemplative adaptation and risk reduction education, although such topics are very sensitive and can trigger memories of grief, sorrow and vulnerability (Wamsler 2015/2016). This contrasts with an increase in neuroscience-based mental health science and mindfulness training offered by private organizations to assist people (including students and professionals) to cope with and address climate-enhanced adversities (cf. Sect. “Mindfulness and sustainability in practice”). One example is the International Transformational Resilience Coalition and the program offered by The Resource Innovation Group in partnership with Resilience Training International and the Trauma Resource Institute that aims to enhance personal, collective, and environmental well-being (Doppelt 2016).

Discussion and conclusions: Integrating mindfulness into sustainability research, practice, and teaching

The results of this study show that there is a theoretical, conceptual, and empirical blind spot in the academic debate on mindfulness in sustainability research, practice, and teaching.Footnote 26 This is alarming, since sustainability encompasses not only ecological and economic, but also social dimensions at all scales. Sustainability is ultimately a social choice. It is about what to develop, what to sustain, and for how long (Parris and Kates 2003), and is thus also a deeply normative process (Kemp and Martens 2007). Consequently, individual and subjective modes of being, such as mindfulness, play a crucial role in the context of the scientific inquiry, practice, and teaching of sustainability.

Current knowledge on mindfulness in sustainability is both scarce and fragmented; however, it is gaining increasing momentum. The field is only just emerging; nearly all of the relevant literatures has been published in the past 5 years. While there appears to be increasing consideration of mindfulness in sustainability research, practice, and teaching, most is related to practice.

In research, most progress relates to mindfulness in reactive adaptation and risk reduction during disaster response and recovery. Related work focuses on agency-based solutions, but does not address how this could be translated into structural, systemic change. Little attention is given to pro-active adaptation and risk reductionFootnote 27 and sustainability science in general, related scientific inquiry and methods.

In practice, most progress has been made in the field of climate change mitigation. Mindfulness approaches are based on compassion and positive emotion, unlike the “motivation by fear” and “crisis approach” strategies often found in climate change communications and responses (Ryan 2016). In contrast, little explicit consideration is given to sustainability practice in general, and anticipatory adaptation and risk reduction practice in particular.

In education, most progress relates to an increased recognition of contemplative teaching, although there is no explicit consideration given to the domain of sustainability science (including adaptation and risk reduction). This is in stark contrast to the potential role of science education in mediating the structure and function of the brain to support sustainable change (Powietrzynska et al. 2015).

The literature review did not find any structural critiques of the potential drawbacks of mindfulness in the specific context of sustainability (in research, practice, and education). Nevertheless, there are critiques regarding mindfulness, in general. Concerns have been voiced about potential side-effects (Howard 2016), the inappropriate use of techniques (Williams and Kabat-Zinn 2011; Purser and Loy 2013), and the potential co-optation of mindfulness for capitalist purposes (Carrette and King 2005), stripping it of its transformative power. A reflexive approach to sustainability is key to addressing such concerns in research, practice, and teaching.

This study identified key aspects relevant to mindful inquiry, practice, and education in sustainability, which were developed into a framework for systematizing and analyzing the interlinkages between mindfulness and sustainability from the individual to the global scale (Fig. 1). These aspects are culturally shaped and include: (1) subjective well-being; (2) activation of (intrinsic/ non-materialistic) core values; (3) consumption and sustainable behavior; (4) the human–nature connection; (5) equity issues; (6) social activism; and (7) deliberate, flexible, and adaptive responses to climate change. The framework thus supports the understanding that mindfulness can be seen as a key concept to politically sensitizing people and organizations to the consequences of unquestioned structures and power relations (cf. Senghaas-Knobloch 2014 and “Mindfulness in general sustainability practice”). The mindfulness-sustainability framework can broaden the spatial horizon and help to understand impacts on (distant) communities that might be incongruent with declared values. Understood in this way, mindfulness is no longer a concept that only addresses cognitions and cognitive schemes, but also fosters a sense of appropriate or just behavior (cf. Senghaas-Knobloch 2012). It, therefore, bridges the gap between individual and global scales and wider socio-political structures (cf. Fig. 1, Sects. “Mindfulness in general sustainability research” and “Mindfulness in general sustainability practice”).

The framework positions mindfulness within sustainability science, which may result in more nuanced understandings and perceptions, inspire action, and enhance sustainable change. It may lead to more expansive and inclusive research and (writing) methods that enable people to take risks—the kind of risks that cannot be taken when academic fiefdoms determine the questions that are asked and regulate methodologies, rather than encourage creativity (cf. Mueller and Greenwood 2015).

Science has always been shaped by current problems, and it evolves with them. Climate and disaster risk is global, complex, pervasive, and a new subject of scientific inquiry. Until now, reductionist, natural science research has been taken as the intellectual and social model. However successful, it has been in the past, emerging policy issues and research on neuroplasticity, emotions and mindfulness show that this ideal of rationality is no longer appropriate. Recent developments raise questions about the ontological frameworks and the materialist paradigm that shape the construction of knowledge in general (Osborne and Grant-Smith 2015; Schwartz 2011), and sustainability knowledge and science in particular. Non-material causation need to be recognized as part of sustainability (cf. Sect. “Mindfulness in general sustainability research”).

Hence, theory and research on both sustainability and mindfulness would benefit from synergies towards sustainable change. On one hand, mindfulness research can enhance sustainability science by better linking all scales: from the individual to the global, and advancing ontological questions of scientific inquiry. On the other hand, sustainability science can enhance mindfulness research. In particular, it makes it possible to go beyond agency-based approaches, and examine interdependencies, related power issues, and mindfulness from a decontextualized perspective. In this context, it is important to recognize cultural differences (cf. Christopher et al. 2008, 2009; Kabat-Zinn 2003), which can be embraced through transdisciplinary approaches that encourage cross-cultural exchanges and create new understandings of sustainability (Chinn 2015).

While there are still many unanswered questions in the separate fields of sustainability and mindfulness, reconciling the two areas may open up opportunities for a more profound understanding. Sustainability requires an understanding of causes, consequences and the dynamics of a holistic, interdependent form of well-being in which mindfulness (and associated emotional intelligence) is an important aspect. Rather than looking at active mindfulness interventions and how they play out (e.g. Jacob et al. 2009), further research should also look at individual mindfulness disposition and link it to sustainability. This would open the way for a broader discussion on the role of mindfulness, inner transition, and spirituality in general, in sustainability. It excludes the isolated consideration of individual aspects (e.g., empathy) and erroneous applications of mindfulness that are also deployed to support consumerist values and capitalism that lie at the root of unsustainability (Becker 2015; Weil 2016; Williams and Kabat-Zinn 2011).

We conclude that mindfulness can contribute to understanding and facilitating not only individual, but societal sustainability at all scales. It should, therefore, be considered as a core concept in sustainability research, practice, and teaching. We end with a call for more sustainability research that acknowledges positive emotional connections, spirituality, and mindfulness in particular, recognizing that the micro and macro are mirrored and interrelated.

Notes

Research has shown that emotional intelligence (including self-awareness, self-regulation, social awareness, and relationship management) can be increased through mindfulness practice and associated greater arousal of the brain’s left hemisphere (Goleman 2011).

For instance, theories of reflective self-consciousness and integrative awareness (Brown et al. 2007).

In this paper, ‘sustainability’ describes the meeting point of ideas, policies, and science that address challenges arising from the interaction of natural and social systems to create conditions under which humans and nature can exist in productive harmony to support present and future generations (cf. Scoones 2007). Accordingly, sustainability science seeks to investigate nature–society interactions and to identify creative solutions for more sustainable pathways, by reconciling natural and social sciences and supporting science–policy integration (Kates et al. 2001; Jerneck et al. 2011).

In this paper the terms climate change adaptation, climate adaptation and adaptation are used as synonyms.

The used search string resulted in a considerable number of papers to be reviewed (e.g., 610 in Scopus). However, as the mindfulness–sustainability field is still emerging, there were a large number of false positives. The percentages of empirical versus theoretical/ review papers regarding mindfulness and sustainability in research were around 50–50.

The two Masters’ Programs are the Lund University International Master’s Program in Environmental Studies and Sustainability Science (LUMES), run by Lund University Centre for Sustainability Studies (LUCSUS), and the International Master’s Program in Disaster Risk Management and Climate Change Adaptation, run by the Department of Risk Management and Societal Resilience. Mindfulness approaches were first integrated into the course design in 2013. Their expansion and subsequent development into a learning lab was initiated in 2015 following discussions with the Pedagogic Academy and a LUMES “Knowledge to Action” student project.

Mainly in relation to the five key aspects of mindfulness established by Baer et al. (2006): observing, describing, acting with awareness, non-judgement, and reactivity, together with related aspects of emotional intelligence established by Goleman (2011): self-awareness, self-regulation, social awareness (including empathy, and compassion) and relationship management.

Original title: Sustainability, Mindfulness, and Compassion.

Due to the explorative and qualitative character of this study, there were no control groups. In theory, students who did not participate in the mindfulness sessions could have been used as the control group. However, the response rates were too low.

Based on the research setting, some basic organizational categories were established prior to the data review (categorizing strategy–open coding). Within these primary ‘bins’, patterns were identified (pattern matching–axial coding). The final step was the identification of connections and relationships through a comparison of different categories and patterns (theory building–selective coding) (cf. Wamsler 2007).

See also Egli (1994) for a discussion on the action–reaction relationship between individual and global scales.

This implies a state of mindfulness where people become more aware of environmental impacts and their causes, and adjust their behavior accordingly.

Further research is however called for to look into causality of mindfulness and related methodological challenges, which was outside the scope of this research. Further note that supporting references include empirical studies or systematic reviews of studies that report empirical data (e.g., Khoury et al. 2013). .

For example, studies have identified positive feedback loops between: (1) mindfulness, subjective well-being, equity issues, and social activism (e.g. Shah et al. 2012); (2) mindfulness, the human–nature connection, subjective well-being and pro-environmental behavior (e.g. Barbaro and Pickett 2016); and (3) mindfulness, intrinsic values, subjective well-being, and pro-environmental behavior (e.g. Brown and Kasser 2005).

An exception is Lyles (2015) who looks into the potential of applying compassion building programs for sustainable planning in general, and risk reduction and adaptation planning in particular.

For example, the International Society of Sustainability Professionals, EcoSTEPS (Crawford 2013).

See “Mindfulness in general sustainability research” and Yeh (2006) for related discussions on the principle of dependent origination and its link to sustainable development. For further discussions on mindfulness as a politically sensitizing concept see Senghaas-Knobloch (2012, 2014), Becke (2014) and Becke et al. (2012).

Mindfulness, mental focus and contemplation are associated with many religions and spiritual traditions. For a discussion on mindfulness in Christianity see, for instance, Hanh (2000).

For example, https://vimeo.com/116373704.

For example, the Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education (ACMHE) that was founded in 2008.

Adjectival education refers to the segmentation of knowledge fields (including sustainability science) into separate domains.

At the University of Wisconsin, a “Mindful Climate Action” education program was, for instance, designed to help decrease carbon footprints while enhancing personal health and happiness.

“Theoretical” refers to the foundational theories and associated research that link mindfulness and sustainability, while “conceptual” refers to their operationalization into frameworks for research, practice and teaching.

Note that Collins (2015) highlighted the need for learning and decision making in risk reduction planning based on both experience, and intuition in order to capture imaginative responses that might be supported by mindfulness (cf. Dane 2011; Remmers et al. 2015). This is for instance an area that has not, so far, been explored in any detail.

References

AASHE (2016) Contemplative environmental practice. AASHE (Association for the Advancement of Sustainability in Higher Education), bulletin 2016 (12/05/2016)

ACMHE (2016) Transforming higher education: fostering contemplative inquiry, community, and social action. In: The 8th annual conference of ACMHE, the Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education

Albrecht NJ, Albrecht PM, Cohen M (2012) Mindfully teaching in the classroom: a literature review. Aust J Teach Educ 37(12):1–14

Amel EL, Manning CM, Scott BA (2009) Mindfulness and sustainable behavior: Pondering attention and awareness as means for increasing green behavior. Ecopsychology 1(1):14–25

AMRA (2016) Database of the American Mindfulness Research Association (AMRA). https://goamra.org/resources/. Accessed 1 June 2016

Anthony R (2013) Animistic pragmatism and native ways of knowing: adaptive strategies for overcoming the struggle for food in the sub-Arctic. Int J Circumpolar Health 72:1–7

Australian Red Cross (2015) After the emergency podcast. Mindfulness meditation from Smiling Mind. http://www.redcross.org.au/resilience-newsletter/issue5/2012/01/27/mindfulness.html. Accessed 1 June 2016

Aviles PR, Dent EB (2015) The role of mindfulness in leading organizational transformation: a systematic review. J Appl Manag Entrep 20(3):31–55

Baer RA (2003) Mindfulness training as a clinical intervention: a conceptual and empirical review. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 10(2):125–143

Baer RA, Smith GT, Hopkins J, Krietemeyer J, Toney L (2006) Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment 13:27–45

Barbaro N, Pickett SM (2016) Mindfully green: examining the effect of connectedness to nature on the relationship between mindfulness and engagement in pro-environmental behavior. Pers Individ Differ 93:137–142

Becke G (2014) Mindful change in times of permanent reorganization, CSR, sustainability, ethics and governance. Springer, Berlin

Becke G, Behrens M, Bleses P, Meyerhuber S, Senghaas-Knobloch E (2012) Organizational and political mindfulness as approaches to promote social sustainability. artec paper Nr. 183, artec Forschungszentrum Nachhaltigkeit, Universität Bremen, Germany

Becker AJ (2015) Has mindfulness supplanted thoughtfulness? Christianity Today (CT), 20 April 2015

Biggs J, Tang C (2011) Teaching for quality learning at university, 3rd edn. Open University Press, Maidenhead

Black DSMPH (2010) Hot topics: a 40-year publishing history of mindfulness. Mindfulness Res Mon 1(5):1–5

Boyce B (ed) (2011) The mindfulness revolution. Shambhala Publications, Boulder

Brown KW, Kasser T (2005) Are psychological and ecological well-being compatible? The role of values, mindfulness, and lifestyle. Soc Indic Res 74(2):349–368

Brown KW, Ryan RM (2003) The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol 84:822–848

Brown KW, Kasser T, Ryan RM, Konow J (2004) Having and being: investigating the pathways from materialism and mindfulness to well-being. Unpublished data, University of Rochester

Brown KW, Ryan RM, Creswell JD (2007) Mindfulness: theoretical foundations and evidence for its salutary effects. Psychol Inq 18(4):211–237

Bruce B, Grabow M, Middlecamp C, Mooney M, Checovich MM, Converse AK, Gillespie B, Yates J (2016) Mindful climate action: health and environmental co-benefits from mindfulness-based behavioral training. Sustainability 8:1040

Buss AH (1980) Self-consciousness and social anxiety. Freeman, San Francisco

Carmody J, Baer RALB, Lykins E, Olendzki N (2009) An empirical study of the mechanisms of mindfulness in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Clin Psychol 65(6):613–626

Carrette J, King R (2005) Selling spirituality: the silent takeover of religion. Routledge, London

Carver CS, Scheier MF (1981) Attention and self-regulation: a control-theory approach to human behavior. Springer, New York

Catani C, Kohiladev M, Ruf M, Schauer E, Elbert T, Neuner F (2009) Treating children traumatized by war and Tsunami: a comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in North-East Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry 9(1):1–11

Chadwick A (2013) The hybrid media system: politics and power. Oxford University Press, UK

Chinn PWU (2015) Place and culture-based professional development: cross-hybrid learning and the construction of ecological mindfulness. Cult Stud Sci Educ 10:121–134

Christopher MS, Christopher V, Charoensuk S (2008) Assessing “Western” mindfulness among Thai Theravada Buddhist monks. Ment Health Relig Cult 12(3):303–314

Christopher MS, Charoensuk S, Gilbert BD, Neary TJ, Pearce KL (2009) Mindfulness in Thailand and the United States: a case of apples versus oranges? J Clin Psychol 65(6):590–612

Collins A (2015) Beyond experiential learning in disaster and development communication. In: Egner H, Schorch M, Voss M (eds) Learning and calamities—practices, interpretations, patterns. Routledge, New York

Condon P, Desbordes G, Miller W, DeSteno D (2013) Meditation increases compassionate responses to suffering. Psychol Sci 24(10):2125–2127

Crawford J (2013) Spirituality—at the heart of sustainability. In: Presentation at the ISSP conference, Chicago, International Society of Sustainability Professionals (ISSP), Making Sustainability Standard Practice, 10 May 2013

Csikszentmihalyi M (1997) Finding Flow: the psychology of engagement with everyday life. Basic Books, New York

Dane E (2011) Paying attention to mindfulness and its effects on task performance in the workplace. J Manag 37:997–1018

Davidson RJ, Kabat-Zinn J, Schumacher J, Rosenkranz M, Muller D, Santorelli SF, Saki F, Urbanowski F, Harrington A, Bonus K, Sheridan JF (2003) Alterations in brain and immune function produced by mindfulness meditation. Psychosom Med 65(4):564–570

Dharma Teachers International (2014) Dharma Teachers International collaborative statement on climate change: the earth as witness. Retrieved 10/04/2016 from https://sites.google.com/a/trig-cli.org/dticcc/climate-statement

Doetsch-Kidder S (2012) Social change and intersectional activism: the spirit of social movement. Palgrave Macmillian, New York

Doherty TJ, Clayton S (2011) The psychological impacts of global climate change. Am Psychol 66:265–276

Doppelt B (2016) Transformational resilience: how building human resilience to climate disruption can safeguard society and increase wellbeing. Greenleaf Publishing Limited, UK

Doty JR (2016) Into the magic shop: A neurosurgeon’s quest to discover the mysteries of the brain and the secrets of the heart (Kindle Edition). Avery. Penguin Group, USA

Duval S, Wicklund RA (1972) A theory of objective self-consciousness. Academic, New York

Edwards A (2015) The heart of sustainability: restoring ecological balance from the inside out. New Society Publishers, Canada

Egli R (1994) The LOLA principle. Editions d’Olt, Oetwil a.d.L., Switzerland

Ericson T, Kjønstad BG, Barstad A (2014) Mindfulness and sustainability. Ecol Econ 104:73–79

Eriksen C, Ditrich T (2015) The relevance of mindfulness practice for trauma-exposed disaster researchers. Emot Sp Soc 17:63–69

Fabbrizzi S, Maggino F, Marinelli N, Menghini S, Ricci C (2016) Sustainability and well-being: the perception of younger generations and their expectations. Agric Agric Sci Proc 8:592–601

Gibson T, Wisner B (2016) ‘Lets talk about you ...’—opening space for local experience, action and learning in disaster risk reduction. Disaster Prev Manag 25(5):664–684

Glaser BG, Strauss AL (1967) The discovery of grounded theory: strategies for qualitative research. Aldine de Gruyter, New York

Goleman D (2009) Ecological intelligence: how knowing the hidden impacts of what we buy can change everything. Doubleday, New York

Goleman D (2011) The brain and emotional intelligence: new insights. More than Sound, USA

Greenberg MT, Harris AR (2012) Nurturing mindfulness in children and youth: current state of research. Child Dev Perspect 6(2):161–166

Greenwood D (2013) A critical theory of place-conscious education. In: Stevenson R, Brody M, Dillon J, Wals AJ (eds) International handbook of research on environmental education. Routledge, New York, pp 93–100

Gugerli-Dolder B, Frischknecht-Tobler U (eds) (2011) Umweltbildung Plus. Impulse zur Bildung für nachhaltige Entwicklung. Verlag Pestalozzianum, Zürich

Gugerli-Dolder B, Traugott E, Frischknecht-Tobler U (2013) Emotionale Kompetenzen in der Bildung für Nachhaltige Entwicklung, BNE-Konsortium COHEP, Schweizerische Koordinationskonferenz Bildung für eine Nachhaltige Entwicklung, Zürich, Switzerland

Hanh TN (2000). Going home: Jesus and Buddha as brothers. Riverhead, USA

Hanh TN (2015) Statement on climate change for the United Nations. http://plumvillage.org/letters-from-thay/thich-nhat-hanhs-statement-on-climate-change-for-unfccc/. Accessed 1 June 2016

Hanh TN, Weisman A (2008) The world we have: a Buddhist approach to peace and ecology. Parallax Press, Berkeley

Harris DL, Bordere TC (2016) Handbook of social justice in loss and grief: exploring diversity, equity, and inclusion (series in death, dying, and bereavement). Routledge, London, p 278

Hechanova RM, Ramos PAP, Waelde L (2015) Group-based mindfulness-informed psychological first aid after Typhoon Haiyan. Disaster Prev Manag: Int J 24(5):610–618

Hoeberichts JH (2012) Teaching council in Sri Lanka: a post disaster, culturally sensitive and spiritual model of group process. J Relig Health 51(2):390–401

Hölzel BK, Carmody J, Vangel M, Congleton C, Yerramsetti SM, Gard T, Lazar SW (2011) Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Res 191(1):36–43

Howard SJ (2016) Mindfulness may have risks as well as benefits. J R Soc Med 109(7):259–260

Howell AJ, Dopko RL, Passmore HA, Buro K (2011) Nature connectedness: Associations with well-being and mindfulness. Pers Individ Differ 51(2):166–171

Hülsheger UR, Alberts HJ, Feingold A, Lang JW (2013) Benefits of mindfulness at work: the role of mindfulness in emotion regulation, emotional exhaustion, and job satisfaction. J Appl Psychol 98(2):310

Illeris K (2009) A comprehensive understanding of human learning. In: Illeris K. (ed) Contemporary theories of learning. Routledge, London, pp 7–20

IMS (Institute for Mindfulness Studies) (2015) Mindfulness and the teacher. http://themindfulteacher.com/Home.html. Accessed 28 Aug 2015

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (2001) Third assessment report (TAR). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) (2014) Climate change 2014: impacts, adaptation, and vulnerability. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Jacob J, Jovic E, Brinkerhoff MB (2009) Personal and planetary well-being: mindfulness meditation, pro-environmental behavior and personal quality of life in a survey from the social justice and ecological sustainability movement. Soc Indic Res 93(2):275–294

Jerneck A, Olsson L, Ness B, Anderberg S, Baier M, Clark E, Hickler T, Hornborg A, Kronsell, Lövbrand E, Persson J (2011) Structuring sustainability science. Sustainability Sci 6(1):69–82

Jones RG (2015) Psychology of sustainability: an applied perspective. Routledge, New York

Kabat-Zinn J (1990) Full catastrophe living: using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain and illness. Delacourt, NewYork

Kabat-Zinn J (1994/2005) Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in every day life. Piatkus, London

Kabat-Zinn J (2003) Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin Psychol Sci Pract 10:144–156

Kajikawa Y (2008) Research core and framework of sustainability science. Sustainability Sci 3(2):215–239

Kates RW, Clark WC, Corell R, Hall JM, Jaeger CC, Lowe I, McCarthy JJ, Schellnhuber HJ, Bolin B, Dickson NM, Faucheux S, Gallopin GC, Grübler A, Huntley B, Jäger J, Jodha NS, Kasperson RE, Mabogunje A, Matson P, Mooney H, Moore B 3rd, O’Riordan T, Svedin U (2001) Sustainability science. Sci New Ser 292(5517):641–642

Kaza S (2008) Mindfully green. Shambhala Publications, Boulder

Kemp R, Martens P (2007) Sustainable development: how to manage something that is subjective and that never can be reached? Sustain: Sci Pract Policy 3(2):1–10

Khoury B, Lecomte T, Fortin G, Masse M, Therien P, Bouchard V, Chapleau MA, Paquin K, Hofmann SG (2013) Mindfulness-based therapy: a comprehensive meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 33:763–771

Kjell ONE (2011) Sustainable well-being: a potential synergy between sustainability and well-being research. Rev Gen Psychol 15(3):255–266

Koger SM (2015) A burgeoning ecopsychological recovery movement. Ecopsychology 7(4):245–250

Lang D, Wiek A, Bergmann M, Stauffacher M, Martens P, Moll P, Swilling M, Thomas C (2012) Transdisciplinary research in sustainability science: practice, principles, and challenges. Sustain Sci 7(1):25–43

Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Wasserman RH, Gray JR, Greve DN, Treadway MT, McGarvey M, Quinn BT, Dusek JA, Benson H, Rauch SL, Moore CI, Fischl B (2005) Meditation experience is associated with increased cortical thickness. Neuroreport 16(17):1893–1897

Lee JJ (2012) Teaching mindfulness at a public research university. J Coll Charact 13(2):1–6

Lengyel A (2015) Mindfulness and sustainability: utilizing the tourism context. J Sustain Dev 8(9):35–51

Litfin K, Abigail L (2014) Contemplating enormity: climate change. In: Conference presentation/paper. The 6th annual conference of ACMHE, the Association for Contemplative Mind in Higher Education

Lockhart H (2011) Spirituality and nature in the transformation to a more sustainable world: perspectives of South African change agents. Stellenbosch University, Doctoral dissertation

Lu H, Schuldt J (2016) Compassion for climate change victims and support for mitigation policy. J Environ Psychol 45:192–200

Luders E, Toga AW, Lepore N, Gaser C (2009) The underlying anatomical correlates of long-term meditation: larger hippocampal and frontal volumes of gray matter. Neuroimage 45:672–678

Lyles W (2015) Compassion building practices to improve hazard mitigation and climate adaptation planning. In: Conference paper, 2015 ACSP (Association of Collegiate Schools of Planning) conference, Houston, USA

Macy JR, Young Brown M (1998) Coming back to life: practices to reconnect our lives, our world. New Society Publishers, Canada

Maibach E, Leiserowitz A, Roser-Renouf C, Myers T, Rosenthal S, Feinberg G (2015) The Francis Effect: How Pope Francis changed the conversation about global warming. George Mason University Center for Climate Change Communication, Fairfax

Matanle P (2011) The great east japan earthquake, tsunami and nuclear meltdown: towards the (re)construction of a safe, sustainable, and compassionate society in Japan’s shrinking regions. Local Environ 16(9):823–847

McDonald C, Hendersson H, Brossmann J, Kristjansdottir R, Scarampi P (2016) Raising resilience: exploring the potential of applying mindfulness in disaster risk management. Unpublished course paper, LUCSUS, Lund, Sweden

McKinney F (1976) Free writing as therapy. Psychotherapy 13(2):183–187

Medin AH, Lindberg A (2013) Benefits of a mindfulness and compassion-based intervention for students in academia: a pilot study. Gothenburg University, Sweden

Meiklejohn J, Phillips C, Freedman ML, Griffi ML, Biegel G, Roach A, Isberg R. (2012) Integrating mindfulness training into K-12 education: fostering the resilience of teachers and students. Mindfulness 3(4):291–307

Mendelson T, Greenberg MT, Dariotis JK, Gould LF, Rhoades BL, Leaf PJ (2010) Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. J Abnorm Child Psychol 38(7):985–994

Mueller MP, Greenwood DA (2015) Ecological mindfulness and cross-hybrid learning: a special issue. Cult Scie Edu 10(1):1–4

Neff KD, Germer CK (2013) A pilot study and randomized controlled trial of the mindful self-compassion program. J Clin Psychol 69(1):28–44

Now Unlimited (2015) Ecological mindfulness. http://nowunlimited.co.uk/ecological-mindfulness/. Accessed 10 May 2016

O’Leary K, Dockray S (2015) The effects of two novel gratitude and mindfulness interventions on well-being. J Altern Complement Med 21(4):243–245

One Earth Sangha (2016a) Convergence for climate justice in New Orleans & Lifting the moral voice for climate action. https://oneearthsangha.org/articles/2016/04/. Accessed 4 May 2016

One Earth Sangha (2016b) Contemplative environmental practice: retreat for academicians and activists. https://oneearthsangha.org/events/contemplative-environmental-practice-retreat-for-academicians-and-activists/. Accessed 10 April 2016

Osborne N, Grant-Smith D (2015) Supporting mindful planners in a mindless system: limitations to the emotional turn in planning practice. Town Plan Rev 86(6):677–698

Parris TM, Kates RW (2003) Characterizing and measuring sustainable development. Annu Rev Environ Resour 28:559–586

Powietrzynska M, Tobin K, Alexakos K (2015) Facing the grand challenges through heuristics and mindfulness. Cult Sci Educ 10(1):65–81

Purser R, Loy D (2013) Beyond McMindfulness. Blog. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ron-purser/beyond-mcmindfulness_b_3519289.html. Accessed 1 June 2016

Ragoonaden K (ed) (2015) Mindful teaching and learning: developing a pedagogy of well-being. Lexington Books

Remmers C, Topolinski S, Michalak J (2015) Mindful(l) intuition: does mindfulness influence the access to intuitive processes? J Posit Psychol 10(3):282–292

Rinne J, Lyytimäki J, Kauttp P (2013) From sustainability to well-being: lessons learned from the use of sustainable development indicators at national and EU level. Ecol Indic 35:35–42

Rogerson PA, Kim D (2005) Population distribution and redistribution of the baby-boom cohort in the United States: recent trends and implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102(43):15319–15324

Ryan K (2016) Incorporating emotional geography into climate change research: a case study in Londonderry, Vermont, USA. Emot Sp Soc 19:5–12

Sameshima P, Greenwood DA (2015) Visioning the centre for place and sustainability studies through an embodied aesthetic wholeness. Cult Sci Educ 10(1):163–176

Schley S (2011) Sustainability: the inner and outer work. Oxf Leadersh J: Shift Traject Civilis 2

Schoeberlein D (2009) Mindful teaching and teaching mindfulness: a guide for anyone who teaches. Wisdom Publications, USA

Schonert-Reichl KA, Roeser RW (eds) (2016) Handbook of mindfulness in education: integrating theory and research into practice. Springer, New York

Schutte NS, Malouff JM (2011) Emotional intelligence mediates the relationship between mindfulness and subjective well-being. Personal Individ Differ 5(7):1116–1119

Schwartz JM (2011) Mindfulness and materialist paradigm: mind-brain interaction and the breakdown of the materialist paradigm. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ff2cnQ69LK8. Accessed 2 May 2016. Linked to Schwartz JM, Gladding R (2011) You are not your brain. Avery, New York

Scoones I (2007) Sustainability. Dev Pract 17(4–5):589–596

Senge P, Laur J, Schley S, Smith B (2006) Learning for sustainability. SOL, Cambridge

Senghaas-Knobloch E (2012) When the concept of mindfulness ‘travels’ to the realm of politics: a new look on the global care crisis as a challenge for socially sustainable development. In: Organizational and political mindfulness as approaches to promote social sustainability. artec paper Nr. 183, artec Forschungszentrum Nachhaltigkeit, Universität Bremen

Senghaas-Knobloch E (2014) Mindfulness: a politically sensitizing concept. care and social sustainability as issues. In: Becke G (ed) Mindful change in times of permanent reorganization. CSR, sustainability, governance ethics. Springer, Berlin, pp 191–208

Shah AK, Mullainathan S, Shafir E (2012) Some consequences of having too little. Science 338(6107):682–685

Shapiro SL, Carlson LE, Astin JA, Freedman B (2006) Mechanisms of mindfulness. J Clin Psychol 62(3):373–386

Sheth, J, Sethia, N, Srinivas, S (2010) Mindful consumption: a customer-centric approach to sustainability. J Acad Mark Sci 39(1):21–39

Siqueira R, Pitassi C (2016) Sustainability-oriented innovations: can mindfulness make a difference? J Clean Prod 139:1181–1190

Smith BW, Ortiz JA, Steffen LE, Tooley EM, Wiggins KT, Yeater EA, Montoya JD, Bernard ML (2011) Mindfulness is associated with fewer symptoms, depressive symptoms, physical symptoms, and alcohol problems in urban firefighters. J Consult Clin Psychol 79(5):613

Sol J, Wals AEJ (2015) Strengthening ecological mindfulness through hybrid learning in vital coalitions. Cult Sci Educ 10(1):203–214

Srivatsa UN, Ekambaram V Jr, Saint Phard W, Cornsweet D (2013) The effects of a short term stress alleviating intervention (SAI) on acute blood pressure responses following a natural disaster. Int J Cardiol 168(4):4483–4484

Strauss AL, Corbin J (1998) Basics of qualitative research. Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Sumi A (2007) On several issues regarding efforts toward a sustainable society. Sustain Sci 2(1):67–76

Sutcliffe KM (2011) High reliability organizations (HROs). Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 25(2):133–144

Tang YY, Lu Q, Fan M, Yang Y, Posner MI (2012) Mechanisms of white matter changes induced by meditation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109(26):10570–10574

Thompson RW, Arnkoff DB, Glass CR (2011) Conceptualizing mindfulness and acceptance as components of psychological resilience to trauma. Trauma Violence Abuse 12(4):220–235

Townsend M (2013) Could mindfulness hold the key to unlock a sustainable future? 2 degrees. Community, Earthshine Solutions Ltd. https://www.2degreesnetwork.com/groups/2degrees-community/resources/could-mindfulness-hold-key-unlock-sustainable-future/. Accessed 10 June 2016 (cf. The Quiet Revolution: We have more choices than we think [Greenleaf, Shipley, forthcoming])

Vaughan-Lee L (ed) (2013) Spiritual ecology: the cry of the earth. The Golden Sufi Centre, USA

Vestergaard-Poulsen P, van Beek M, Skewes J, Bjarkam CR, Stubberup M, Bertelsen J, Roepstorff A (2009) Long-term meditation is associated with increased gray matter density in the brain stem. Neuroreport 20(2):170–174

Waelde LC, Uddo M, Marquett R, Ropelato M, Freightman S, Pardo A, Salazar J (2008) A pilot study of meditation for mental health workers following Hurricane Katrina. J Trauma Stress 21(5):497–500

Wals AEJ, Corcoran PB (eds) (2012) Learning for sustainability in times of accelerating change. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen

Wamsler C (2007) Managing urban disaster risk: analysis and adaptation frameworks for integrated settlement development programming for the urban poor (methodology section). Lund University, Lund

Wamsler C (2015/2016) Teaching portfolio. Teaching Academy, Lund University, Lund

Weaver L, Wilding M (2013) The 5 dimensions of engaged teaching. Solution Tree Press, Bloomington

Weger UW, Hooper N, Meier BP, Hopthrow T (2012) Mindful maths: reducing the impact of stereotype threat through a mindfulness exercise. Conscious Cogn 21(1):471–475

Weick KE, Sutcliffe KM (2007) Managing the unexpected. 2nd edition. Wiley, San Francisco

Weil Z (2016) Empathy + thinking = wise action. Common Dreams: Breaking News and Views for the Progressive Community. Published on April 12, 2016. http://www.commondreams.org/views/2016/04/12/empathy-thinking-wise-action. Accessed 1 June 2016

Williams JMG, Kabat-Zinn J (2011) Mindfulness: diverse perspectives on its meaning, origins, and multiple applications at the intersection of science and dharma. Contemp Buddh 12(01):1–18

Wisner BL (2014) An exploratory study of mindfulness meditation for alternative school students: perceived benefits for improving school climate and student functioning. Mindfulness 5(6):626–638

Wolpow R, Johnson MJ, Hertel R, Kincaid SO (2009) The heart of learning and teaching: compassion, resiliency and academic success. Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instructions (OSPI), Compassionate Schools, Washington

Yeh, TD-I (2006) The way to peace: a buddhist perspective. Int J Peace Stud 11(1):91–112

Yoshimura M, Kurokawa E, Noda T, Hineno K, Tanaka Y, Kawai Y, Dillbeck MC (2015) Disaster relief for the Japanese earthquake–tsunami of 2011: stress reduction through the transcendental meditation technique 1, 2, 3. Psychol Rep 117(1):206–216

Zajonc A (2016) Contemplation in education. In: Schonert-Reichl KA, Roeser RW (eds) Handbook of mindfulness in education: integrating theory and research into practice. Springer, New York, pp 17–28

Zeller M, Yuval K, Nitzan-Assayag Y, Bernstein A (2015) Self-compassion in recovery following potentially traumatic stress: longitudinal study of at-risk youth. J Abnorm Child Psychol 43(4):645–653

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handled by Michael O’Rourke, Michigan State University, USA.

Appendices: Experimental learning lab

Appendices: Experimental learning lab

Appendix 1: Contemplative teaching and learning practices