Abstract

Effective online teacher professional development (OPD) is crucial to support teachers. The effectiveness of OPD depends on teachers’ engagement. According to offer-use models, teachers’ engagement in OPD relates to the OPD quality and teachers’ motivation to learn. However, whereas OPD activities have increased in recent years, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, findings on the importance of OPD quality and teachers’ motivation to learn for teachers’ engagement in OPD are scarce. We analyzed data from N = 593 teachers participating in 61 OPD courses. The predictive power of perceived OPD quality (i.e., clarity and structure, practical relevance, cognitive activation, and collaboration) and teachers’ motivation to learn for their behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement during OPD were examined using structural equation modeling. We used latent moderated structural equations to gain insights into the interaction effects between OPD quality and teachers’ motivation. Our findings indicate that OPD quality positively predicted teachers’ OPD engagement. When controlling for OPD quality, teachers’ motivation to learn also predicted teachers’ behavioral and cognitive engagement but not their affective engagement. The findings on the interactions between OPD quality and teachers’ motivation demonstrated that for the different facets of teachers’ OPD engagement, different OPD quality characteristics could compensate for low teacher motivation to learn. For instance, for behavioral engagement, opportunities for collaboration can compensate for low motivation. Implications for practice (e.g., ensuring high-quality OPD) and future directions in research (e.g., conducting longitudinal studies) in the field of OPD are discussed.

Zusammenfassung

Wirksame Onlinefortbildungen (OPD) sind für die Unterstützung der Lehrkräfte von entscheidender Bedeutung. Die Wirksamkeit von OPD hängt vom Engagement der Lehrkräfte ab, welches Angebot-Nutzungs-Modellen folgend wiederum mit der Qualität der OPD und der Lernmotivation der Lehrkräfte zusammenhängt. Obwohl die OPD-Aktivitäten in den letzten Jahren zugenommen haben, insbesondere während der COVID-19-Pandemie, gibt es nur wenige Erkenntnisse über die Bedeutung der OPD-Qualität und der Lernmotivation der Lehrkräfte für das Engagement der Lehrkräfte an OPD. Wir analysierten Daten von N = 593 Lehrkräften, die an 61 OPD-Kursen teilnahmen, und untersuchten mit Strukturgleichungsmodellen die Vorhersagekraft der wahrgenommenen OPD-Qualität (d. h. Klarheit und Struktur, praktische Relevanz, kognitive Aktivierung und Zusammenarbeit) und der Lernmotivation der Lehrkräfte für ihr verhaltensbezogenes, affektives und kognitives OPD-Engagement. Zudem haben wir latent moderierte Strukturgleichungen verwendet, um Einblick in die Interaktionseffekte zwischen der OPD-Qualität und der Motivation der Lehrkräfte zu gewinnen. Unsere Ergebnisse zeigen, dass die OPD-Qualität das OPD-Engagement der Lehrkräfte positiv vorhersagt. Unter Kontrolle der OPD-Qualität sagt auch die Lernmotivation der Lehrkräfte das verhaltensbezogene und kognitive Engagement der Lehrkräfte vorher, nicht aber ihr affektives Engagement. Die Ergebnisse zu den Wechselwirkungen zwischen der OPD-Qualität und der Motivation der Lehrkräfte zeigen, dass für die verschiedenen Facetten des OPD-Engagements der Lehrkräfte unterschiedliche OPD-Qualitätsmerkmale eine geringe Lernmotivation der Lehrkräfte kompensieren können. So können z. B. bei verhaltensbezogenem Engagement die Möglichkeiten zur Zusammenarbeit eine geringe Motivation ausgleichen. Es werden Implikationen für die Praxis (z. B. Sicherstellung qualitativ hochwertiger OPD) und künftige Forschungsrichtungen (z. B. Durchführung von Längsschnittstudien) bezüglich OPD diskutiert.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

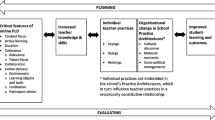

Professional development (PD) is crucial to prepare teachers for professional challenges (Darling-Hammond et al. 2017). In recent years, online professional development (OPD) has become increasingly important (Dede et al. 2009; Meyer et al. 2023), as OPD allows teachers to participate flexibly in terms of time and place, and studies have indicated that teachers benefit from such courses (Morina et al. 2023). For (O)PDFootnote 1 to be effective (e.g., regarding increased teacher knowledge, skills or attitudes, change in instruction, improved student learning; Desimone 2009; Quinn et al. 2019), among other things, it is important for teachers not only to be in attendance but also to be behaviorally, affectively, and cognitively engaged in (O)PD. Engagement is critical to ensure that teachers learn when participating in (O)PD and apply the content of (O)PD to their professional practice (Bragg et al. 2021; Ji 2021). In models of the offer and uses of (O)PD as learning opportunities, such as the one by Lipowsky and Rzejak (2015; for an adapted version specifically for OPD, see Fig. 1), the success of (O)PD (i.e., effectiveness at the teacher and student levels) is explained by an interplay of multiple influencing variables (e.g., quality of [O]PD, perception of [O]PD, characteristics of facilitators and participants, school context; see Fig. 1). According to Lipowsky and Rzejak (2015), teachers’ engagement in (O)PD depends on both characteristics of the (O)PD (e.g., quality of [O]PD) and characteristics of the teachers (e.g., motivation to learn). Regarding the quality of face-to-face PD, studies have demonstrated that characteristics of the quality of PD (e.g., coherence, content focus) are positively related to PD participation and outcomes (e.g., Hauk et al. 2022; Masuda et al. 2013; Penuel et al. 2007), regarding the quality of OPD, Bragg et al. (2021) demonstrated in their systematic review that it can be assumed that certain OPD design elements have the potential to address individual differences and promote participant engagement successfully. Also, research has shown that personal interest in learning (e.g., motivation to learn) is positively related to participation in (O)PD (Jansen in de Wal et al. 2014; D. Richter et al. 2019; Zhang and Liu 2019). It can be assumed that the quality of (O)PD and the characteristics of teachers are related to each other (Harper-Hill et al. 2022). For instance, following the expectancy-value theories (e.g., Wigfield and Eccles 2000), it can be assumed that teachers are more motivated to engage in (O)PD when they perceive a (O)PD program as well-structured, recognize the (O)PD goals, and perceive the content as relevant for their daily professional practice. Teachers are more likely to recognize that their efforts will lead to successful learning outcomes. Regarding teachers’ engagement in (O)PD, this mechanism likely has particular potential for teachers with a lower motivation to learn (i.e., who do not feel the need to engage with learning content in depth).

Offer-use model of online professional development. (This figure was adapted from Lipowsky and Rzejak (2015) regarding online professional development (OPD). Shaded in gray are the areas that were focused on in this study)

However, theoretical frameworks describing the interplay between (O)PD course offerings and (O)PD participation differentiate between (O)PD and teacher characteristics. So far, there has been little attempt to examine their interaction. Therefore, it is an open question whether, for instance, the perception of high (O)PD quality can compensate for low motivation to learn. In addition, most research focused on teachers’ participation in (O)PD but not on teachers’ engagement in (O)PD. Moreover, whereas quality characteristics of face-to-face PD have been frequently the focus of previous research (e.g., content focus, coherence; Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Desimone 2009), quality characteristics of OPD like those suggested by Quinn et al. (2019) have not been frequently the focus. Thus, little is known about the quality of OPD and its importance for its effectiveness (Meyer et al. 2023; Powell and Bodur 2019).

In this study, we analyze data of 593 teachers who participated in an OPD, first, to gain insight into the importance of the quality of OPD and teachers’ learning motivation on teachers’ engagement in OPD and, second, to understand the interactive relationship between the quality of OPD and teachers’ learning motivation regarding their engagement in OPD.

1 Theoretical background

1.1 Teachers’ engagement in (online) professional development

The engagement of individuals is considered an important driving force for successfully processing tasks (Fredricks et al. 2004). Engagement is a motivational construct describing individuals’ voluntary allocation of personal resources to accomplish tasks required by the nature of professions like teaching (Klassen et al. 2013). Engagement is a multidimensional construct comprising at least the three dimensions of physical (or behavioral), affective (or emotional), and cognitive engagement (for student engagement, see Fredricks et al. 2019; for teacher or work engagement, see Klassen et al. 2013) that also apply for teachers’ engagement in (O)PD (Ji 2021). How teachers are engaged during (O)PD (e.g., using different strategies to acquire new knowledge) seems to be relevant for teachers’ learning and even more important than, for instance, teachers’ initial motivation to participate in (O)PD (i.e., whether teachers participate voluntarily; Timperley et al. 2007). Indeed, the findings of several studies indicate a positive association between the engagement of teachers’ participation in a face-to-face PD and the effectiveness of that face-to-face PD (e.g., on teachers’ beliefs; for a collection of studies, see Lipowsky and Rzejak 2015).

Behavioral engagement can be defined as participation in learning opportunities (Fredricks et al. 2016). When applied to (O)PD, teachers’ behavioral engagement is characterized by, among other things, productive participation (e.g., positive conduct, absence of disruptive behavior) in any form of (O)PD (i.e., formal or informal, in-school or out-of-school, face-to-face or OPD). Affective engagement refers to learners’ sentiments regarding a learning opportunity, such as negative or positive reactions to learning opportunity stakeholders (Fredricks et al. 2016). When applied to (O)PD, teachers’ affective engagement is characterized by any sentiments regarding their participation in (O)PD, (O)PD content, (O)PD providers, or (O)PD educators. Cognitive engagement can be related to the concept of self-regulated learning and describes the willingness of the learners to use learning strategies to understand the content as well as possible (Fredricks et al. 2016). When applied to (O)PD, teachers’ cognitive engagement is characterized by the effort teachers invest during (O)PD to learn the (O)PD content and to understand how the content can be applied to their daily practice. Ji (2021) emphasizes that teachers’ face-to-face PD engagement and not just their participation in face-to-face PD (i.e., being physically present) is the factor that is positively related to teacher learning in face-to-face PD. Thus, it becomes apparent that the construct of (O)PD engagement should be separated from that of (O)PD participation/attendance. However, studies often do not distinguish between being in a (O)PD and engaging in a (O)PD. For instance, E. Richter et al. (2021), Fütterer et al. (2023a), and Jansen in de Wal et al. (2014) used the terms teachers’ participation in (O)PD and teachers’ engagement in (O)PD synonymously and thus operationalized teachers’ engagement in (O)PD via (O)PD activities (e.g., workshops) and the duration of participation. Moreover, studies focusing on teachers’ engagement in (O)PD rarely distinguish between the three subdimensions of engagement—behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement.

How engaged teachers are in (O)PD depends on both characteristics of the (O)PD (e.g., quality of [O]PD; for PD, see Desimone 2009; for OPD, see Quinn et al. 2019) and characteristics of the teachers (e.g., motivation to learn; Lipowsky and Rzejak 2015).

1.2 The quality of (online) teacher professional development

In recent decades, key features of effective (mostly face-to-face) PD have been identified (Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Desimone 2009; Lipowsky and Rzejak 2015). For instance, findings from Ji (2021) and Bragg et al. (2021) indicate that opportunities for active learning or the coherence of (O)PD are positively associated with teachers’ engagement in (O)PD. The key features of effective (mostly face-to-face) PD identified by different authors are not identical, and they emphasize different aspects. In the following, we address key aspects congruent in different models and assumed relevance for OPD following Quinn et al. (2019).

First, a characteristic of effective (O)PD derived from teaching effectiveness research is clarity and structure (Seidel and Shavelson 2007). Clarity and structure are characterized, among other things, by the fact that learning objectives are established, which are made transparent to the learners, and activities are structured to achieve these objectives. Regarding face-to-face PD, for instance, Antoniou and Kyriakides (2013) showed that face-to-face PD, characterized by clarity and structure, outperformed face-to-face PD in which teachers reflect on their teaching practice without clarity of the specific content focus and structural support by instructors. Kleickmann et al. (2016) also showed that face-to-face PD in which teachers were systematically guided (scaffolding) was superior to a self-study face-to-face PD approach regarding outcomes ranging from teacher motivation to student achievement.

Second, (O)PD is assumed to be effective when it is coherent. Coherence is characterized by learning content consistent with teachers’ knowledge and beliefs or (school) policies and initiatives (Desimone 2009). One aspect of coherence that Quinn et al. (2019) highlight for OPD, in particular, is the immediate practical relevance of OPD content and goals to teachers’ professional activities. That is, (O)PD should be relevant to teachers’ professional needs (Kleiman and Wolf 2016; see also Darling-Hammond et al. 2009). Although Timperley et al. (2007) emphasize that adult learning is comparable to student learning, they also point out that adults have higher demands regarding the relevance of learning content to engage in learning. OPD specifically offers the potential to address topics where a school or school district has no expertise (i.e., extended interaction with experts who are not onsite; Bates et al. 2016). This enables a just-in-time response to the current needs of teachers, such as knowledge about technological innovations (currently, for example, AI-based technologies such as ChatGPT).

Third, (O)PD should be designed to encourage teachers to learn actively rather than passively. Whereas Desimone (2009) characterized active learning as learning activities in which learners are visibly (i.e., physically) active (e.g., analyzing student work, making presentations), Darling-Hammond et al. (2017) characterized active learning instead by features of cognitive activity of the learners (e.g., connecting to prior knowledge, inquiry learning, interactive learning) that tend to be unobservable and express more profound and more effortful behavior regarding the learning content (see also Chi and Wylie 2014). The latter features are consistent with the findings of teaching effectiveness research on the effectiveness of cognitively activating learning environments (Klieme et al. 2009; Praetorius et al. 2018; Seidel and Shavelson 2007). Lipowsky and Rzejak (2015) explicitly recommend using the findings of teaching effectiveness research to describe key features of effective (O)PD. Regarding face-to-face PD, for instance, Decker et al. (2015) demonstrated that teachers’ level of processing predicted changes in their beliefs. Moreover, a recent study by Meyer et al. (2023) showed that teachers’ cognitive engagement during an OPD is more important than, for instance, the clarity and structure of the OPD for changes in teaching practices after participating in OPD.

Fourth, effective (O)PD should provide sufficient opportunities for collaboration between participants (i.e., interactive learning processes and exchange between learners; Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Quinn et al. 2019). Technologies like collaborative document editing software or video conferencing systems offer real-time synchronous online collaboration (Fishman 2016). This means collaboration should be at least as feasible online as in face-to-face PD. For instance, Landry et al. (2009) showed that a collaborative OPD can be successfully conducted and be effective for teaching and student outcomes. Furthermore, Bragg et al. (2021) showed that a collaborative OPD is associated with teachers’ engagement in OPD.

1.3 Teachers’ motivation in (online) professional development

In recent years, teacher motivation has increasingly emerged as an important aspect of (O)PD participation and effectiveness. For instance, it has been shown that there are different reasons for teachers to participate in (O)PD (Appova and Arbaugh 2018; D. Richter et al. 2019; E. Richter et al. 2022; Rzejak et al. 2014) and that interest in the content of (O)PD is a key driver for teachers’ participation in (O)PD (Bareis et al. 2023; Fütterer et al. 2023b). Whereas this research focuses on motivational orientations before (O)PD participation, there is an increasing focus on teachers’ motivation during (O)PD participation. For instance, Jansen in de Wal et al. (2014) found that teachers with higher levels of identified regulation and intrinsic motivation engaged more in work-related learning activities. This means that teachers interested in (O)PD content or who value their personal development learn more engaged than teachers who are more likely to be constrained by external pressure or perceived obligations. Osman and Warner (2020) emphasized the importance of teachers’ motivation to integrate (O)PD content into practice. Based on the expectancy-value theory, they presented an instrument to measure teachers’ expectations for successful implementation, the value of implementation, and the perceived costs of implementation.

1.4 Research questions

Previous research on teachers’ participation in face-to-face PD (e.g., how engaged teachers are in face-to-face PD) has shown that both face-to-face PD quality characteristics and teacher motivation are important aspects. Although little research has been done on the interplay between the perceived quality of (O)PD and teachers’ motivation to learn (Lipowsky and Rzejak 2015), recent findings for OPD suggest that positive correlations exist (Harper-Hill et al. 2022). However, the underlying mechanisms between the perceived quality of OPD, teachers’ motivation to learn, and their engagement in OPD are unknown. Moreover, most of the findings relate to face-to-face PD rather than OPD. Therefore, in this study, we analyzed the data of 593 teachers who participated in an OPD to gain insights into the importance of OPD quality and teachers’ learning motivation, as well as their interplay for teachers’ engagement in OPD. We address the following research questions (RQ):

(RQ1) How is the perceived quality of teachers’ OPD associated with their engagement in OPD?

Based on the findings on the importance of (O)PD quality for its effectiveness, we assumed that OPD quality characteristics would positively predict teachers’ OPD engagement (i.e., explanatory approach).

(RQ2) How is the motivation of teachers to learn associated with their engagement in OPD?

Based on the findings on the importance of teachers’ (O)PD motivation to learn, we assumed that teachers’ motivation to learn would explain additional (i.e., in addition to OPD quality characteristics) variance in teachers’ OPD engagement (i.e., explanatory approach).

(RQ3) How do the quality of OPD and teachers’ motivation to learn interact regarding teachers’ engagement in OPD?

The independent predictive importance of OPD quality characteristics (RQ1) and teachers’ motivation to learn (RQ2), which leads to a combined effect (i.e., equals the sum of the separate effects), can be described as an additive effect model (Cohen et al. 2003; Trautwein et al. 2015). Beyond an additive effect, we explored whether a synergistic effect (i.e., teachers’ OPD engagement is high when the perceived quality of OPD is high and teachers are highly motivated to learn; see Fig. 2a) or a compensatory effect (i.e., OPD quality and teachers’ motivation to learn compensate for each other; see Fig. 2b) was evident.

2 Method

2.1 Study design

The present study is based on a cross-sectional design to examine associations between OPD quality and teachers’ OPD engagement. The study uses data from a research project funded by the Ministerium für Schule und Weiterbildung of the State of North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany) to develop an instrument for assessing (O)PD quality. In the research project, to evaluate the instrument’s validity and reliability for measuring the quality of (O)PD (Richter and Richter 2023; for validation of the instrument, see Richter and Richter 2024), (O)PD courses were randomly selected from all the (O)PD courses offered in the school year 2021–2022. As part of the data collection, other research instruments were used in addition to the (O)PD quality measurement instrument to obtain information on the psychometric quality of the instrument. Data were collected through online questionnaires at the end of the (O)PD courses. Participants received a web link from the teacher educators to access the survey. The teacher educators were informed in advance about the subject and objectives of the study and received standardized information about the procedure. Two test booklets were used to reduce the time burden on the participants and ensure that the questionnaire could be completed within the course time.

Regarding the characteristics used in this study, the two test booklets encompassed all characteristics in overlapping form (e.g., gender, teaching experience) apart from teachers’ motivation to learn, assessed in only one of the two test booklets. We assigned the participants to the test booklets randomly. Participation in the project was voluntary, and due to data privacy, we do not know how many participants took part in the different (O)PD courses.

Although the research project investigated both face-to-face and online PD, in this study, we focus on the subset of courses that were conducted online. We included a set of 61 OPD courses, which were, on average, comparable in duration to face-to-face PD courses (M = 5.22 h [SD = 2.27], Minimum = 1.5 h, Maximum = 9 h). Most of the OPD courses (90%) were not organized by the school itself (often more mandatory for the participants) but offered by external partners (typically more voluntary), reflecting the real-world variation in OPD participation across different settings and contexts. The OPD courses cover different subject areas: curricula (5.6%), instructional quality (11.1%), teacher-related professionalization (18.5%), subject didactics (22.2%), inclusion/integration of students with special educational needs (20.4%), and school development and organization (22.2%). On average, eleven participants participated in each OPD course. This is an acceptable value because it mainly corresponds to findings from a program analysis for PD in a German federal state, where it was shown that an average of 10 to 12 teachers participate per PD course (Richter et al. 2020).

2.2 Sample

Our sample comprised N = 593 teachers (83% female). Most teachers (43%) had 5 to 15 years of teaching experience, and a slightly smaller group (38%) had more than 15 years of teaching experience. Early career teachers with 0 to 5 years of teaching experience comprised 18% of the participants. 68% of teachers worked full time. The vast majority (88%) were initially trained to become a teacher and completed a mandated induction program (“Referendariat”; 94%). Many teachers (35%) worked at a vocational school (“Berufskolleg”); others worked at primary schools (32%), comprehensive schools (“Gesamtschule”; 10%), or secondary schools (highest track [“Gymnasium”]; 9%).

2.3 Measures

To assess teachers’ engagement in OPD, we assessed indicators of the three established dimensions of engagement: behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement. The indicators were adapted from prior studies (Chan et al. 2021; Pintrich et al. 1991). For all items, participants responded on a 4-point scale (1 = does not apply, 2 = rather does not apply, 3 = rather does apply, 4 = does apply). We assessed behavioral engagement in PD with five items (e.g., “I asked questions”), which showed good internal consistency (Taber 2018) in our data (Cronbach’s alpha [α] = 0.72); affective engagement with four items (e.g., “I am happy to have participated in the course”), which had high internal consistency (α = 0.88); and cognitive engagement with four items (e.g., “During the course, I thought intensively about the content”), which showed good internal consistency (α = 0.72Footnote 2).

To assess the OPD quality perceived by the teachers, we assessed the four dimensions: clarity and structure, practical relevance, cognitive activation, and collaboration. The four dimensions are strongly related to the characteristics of effective PD activities (Darling-Hammond et al. 2017; Desimone 2009). The items were developed in a co-constructive process with teachers. A 4-point scale (1 = do not agree at all, 2 = rather disagree, 3 = rather agree, 4 = fully agree) was applied to all items used to assess the four OPD quality dimensions. We assessed instructional clarity and structure with five items (e.g., “The goals of the course were clearly stated”), which showed high internal consistency in our data (α = 0.87). To assess the practical relevance of OPD, we used four items (e.g., “The aspects covered in the course were related to my current professional practice”), which also showed high internal consistency in our data (α = 0.89). Cognitive activation was assessed with six items (e.g., “My prior knowledge was incorporated into the course”), which showed high internal consistency in our data (α = 0.87). Finally, we assessed collaboration (i.e., opportunity for collaboration) with three items (e.g., “The course allowed for work in small groups”), which showed good internal consistency in our data (α = 0.82).

We assessed teachers’ motivation to learn with four items (e.g., “I like learning new things”; adapted from Gorges et al. 2016) each on a 4-point scale (1 = do not agree, 2 = rather not agree, 3 = rather agree, 4 = agree); these items showed good internal consistency (α = 0.83).

As control variables, we used teacher and course characteristics. Specifically, we used teachers’ sex (0 = male, 1 = female) and their teaching experience (dummy coded: teaching experience 1 [1 = 0 to 5 years of teaching experience], teaching experience 2 [1 = 15 or more years of teaching experience], with teachers who had 6 to 14 years of teaching experience functioning as a reference group). Additionally, we controlled for the duration of the PD courses in hours and the type of PD courses (0 = school external PD, 1 = school internal PD).

All item wordings are in Appendix A.

2.4 Statistical analyses

To answer the first two research questions, we performed structural equation modeling (SEM) using R version 4.2.2 language for statistical computing (R Core Team 2022) and the R package lavaan 0.6-15 (Rosseel 2012) by using RStudio version 2023.3.0.386 (Posit team 2023). To answer the question of how OPD quality is associated with teachers’ engagement in OPD (RQ1), we regressed all three teacher engagement dimensions (i.e., behavioral, affective, and cognitive engagement) on the four OPD quality dimensions (i.e., clarity and structure, practical relevance, cognitive activation, and collaboration). To avoid multicollinearity and especially redundancy effects, we computed a separate SEM for each OPD quality dimension (Model 1 [M1]: clarity and structure, M2: practical relevance, M3: cognitive activation, and M4: collaboration). Next, we additionally regressed OPD engagement on teachers’ motivation in all four models to gain insight into associations between these constructs and to explore how much additional variance in teachers’ OPD engagement is explained by teachers’ motivation (RQ2). To do this, we analyzed the change in the coefficient of determination (i.e., ∆R2) as suggested by Hayes (2021) for SEM using saturated correlates in the reduced models (Graham 2003). To answer the third research question, how OPD quality characteristics and teachers’ motivation to learn interact (RQ3), we performed latent interactions by using the latent moderated structural (LMS) equations approach (Klein and Moosbrugger 2000) as implemented in Mplus 8 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2017). For each OPD engagement dimension and each OPD quality dimension, we computed a separate SEM (M5.1 to M5.12).

To fit the models, we used maximum likelihood parameter estimates. As the multilevel structure of the data (teachers nested within courses) was a “byproduct of the data collection” and not a research question, we wanted to make sure that the estimations sufficiently account for the clustered structure (McNeish et al. 2017, p. 16). Thus, we estimated cluster robust standard errors to account for the nesting structure.

We utilized the standard cutoffs for fit indices to assess the SEMs’ goodness of fit (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA] below 0.08, Comparative Fit Index [CFI] above 0.95, and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual [SRMR] below 0.06; Hu and Bentler 1999). In addition, when possible, we generated dynamic model fit index cutoffs (McNeish amd Wolf 2021) using the R package dynamic version 1.1.0 (Wolf and McNeish 2022) to back up the evaluation of the measurement models. Due to the high number of models computed (cumulative alpha risk), we used the Benjamini-Hochberg (1995) adjustment for multiple testing to control the false discovery rate.

In total, 15% of the values of the dependent variables and 33% of the values of the independent and control variables were missing (i.e., in total, 24%). Values were missing because the participants received different test booklets, and individual items were not answered. Given the results of Little’s test of missing completely at random (MCAR), we can assume that the data are MCAR (62 missing patterns, χ2 (1,572, N = 593) = 1099.86, p = 1.00). We treated missing data by applying a full information maximum likelihood (FIML) approach implemented in lavaan for independent and dependent variables. FIML, as a model-based estimation procedure, typically outperforms traditional methods such as listwise or pairwise deletion (Graham 2012; van Buuren 2018). Although FIML and multiple imputation (MI) procedures lead to similar results when used in SEM (Lee and Shi 2021), we also applied an MI approach to address missing values as a robustness check for the effect sizes due to the relatively large volume of missing values. We generated 50 complete data sets using the R package mice version 3.15.0 (van Buuren and Groothuis-Oudshoorn 2011) and the R package semTools version 0.5‑6 (Jorgensen et al. 2022). We report the standardized regression coefficients.

The analysis code and further information can be viewed in our OSF project: https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/EQRCP.

3 Results

3.1 Descriptive statistics

First, to get an overview of the data, we looked at the descriptive statistics of all scales used (manifest; see Table 1). We found that for most scales, participants rated the items very positively, resulting in high average scores. Noteworthy is the minimum of the scale motivation to learn, which was 2.25. Motivation to learn ratings resulted in relatively low variance compared to the other scales. In addition, all mean values of the sample were above the theoretical scale mean of 2.5, which descriptively means that the scales were highly rated by the teachers compared to the theoretical scale mean.

Second, to evaluate the fit to our data of all measurement models of the latent constructs used in our analyses, we evaluated the model fit indices RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR for each construct separately. All constructs satisfied both the thresholds for good-fitting SEMs of Hu and Bentler (1999) and the dynamic thresholds (see Appendix B). We then evaluated the model fit indices of the multifactor model, in which all constructs were included simultaneously. According to Hu and Bentler (1999), the multifactor models (including the construct motivation to learn) showed almost good fits to the data, M1 (Clarity and Structure): SRMR = 0.071, RMSEA = 0.043, CFI = 0.949; M2 (Practical Relevance): SRMR = 0.069, RMSEA = 0.042, CFI = 0.954; M3 (Cognitive Activation): SRMR = 0.062, RMSEA = 0.037, CFI = 0.962; M4 (Collaboration): SRMR = 0.078, RMSEA = 0.049, CFI = 0.936.

3.2 The quality of OPD and teachers’ OPD engagement

To gain insights into the association between the quality of OPD perceived by teachers and teachers’ OPD engagement (RQ1), we first looked at the correlations between the independent and dependent variables (Table 2). All scales correlated positively and statistically significantly except for the correlations between the motivation to learn scale and the OPD quality characteristics. Next, we evaluated the results of the SEM models M1.1 to M4.1, shown in Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6.

First, M1.1 in Table 3 shows clarity and structure as positive and statistically significant predictor of all three OPD engagement scales. Specifically, the more participants perceived an OPD to have clarity and structure, the higher their ratings of behavioral (β = 0.30, p < 0.001), affective (β = 0.82, p < 0.001), and cognitive engagement (β = 0.66, p < 0.001) retrospectively. Clarity and structure was most important for affective engagement, for which 68% of the variance could be explained together with the control variables. Second, looking at M2.1 in Table 4, practical relevance was also a positive and statistically significant predictor of all three engagement scales. That is, the more teachers perceived an OPD as relevant to their profession, the higher they rated their behavioral (β = 0.41, p < 0.001), affective (β = 0.78, p < 0.001), and cognitive engagement (β = 0.64, p < 0.001) during the OPD in retrospect. Also, practical relevance was most important for affective engagement, for which 61% of the variance could be explained with the control variables. Third, looking at M3.1 in Table 5, cognitive activation was another positive and statistically significant predictor of all three engagement scales. That is, the more teachers perceived an OPD to be cognitively activating, the higher they rated their behavioral (β = 0.44, p < 0.001), affective (β = 0.88, p < 0.001), and cognitive engagement (β = 0.76, p < 0.001) during the OPD in retrospect. Also, cognitive activation was most important for affective engagement, for which 80% of the variance could be explained with the control variables. Finally, looking at M4.1 in Table 6, collaboration was also a positive and statistically significant predictor of all three engagement scales. That is, the more teachers perceived opportunities to collaborate during an OPD, the higher they rated their behavioral (β = 0.61, p < 0.001), affective (β = 0.35, p < 0.001), and cognitive engagement (β = 0.33, p < 0.001) during the OPD in retrospect. Collaboration was most important for behavioral engagement, for which 36% of the variance could be explained with the control variables.

3.3 Teachers’ motivation to learn and teachers’ OPD engagement

To gain insights into how teachers’ motivation to learn is associated with teachers’ OPD engagement (RQ2) and how much variance teachers’ motivation can explain in addition to perceived OPD quality, we looked at the results of the SEM models M1.2 to M4.2 shown in Tables 3, 4, 5 and 6.

First, looking at M1.2 in Table 3, controlling for teachers’ perception of clarity and structure, teachers’ motivation to learn was a positive and statistically significant predictor of teachers’ behavioral (β = 0.30, p = 0.004) and cognitive engagement (β = 0.30, p < 0.001). Teachers’ motivation to learn was a statistically significant predictor of the two dimensions of OPD engagement when the perceived quality of OPD (i.e., clarity and structure) did not explain the most variance. This also means that teachers’ motivation to learn could explain an additional variance of 8.1% of teachers’ behavioral engagement and 8.2% of teachers’ cognitive engagement. In contrast, the additional variance explanation for affective engagement was only 1.3%. This same pattern of findings was found for all three of the other OPD quality characteristics (i.e., practical relevance [see M2.2 in Table 4], cognitive activation [see M3.2 in Table 5], and collaboration [see M4.2 in Table 6]).

3.4 The interaction of the quality of OPD and teachers’ motivation to learn

To gain insights into the interaction between the perceived quality of OPD and teachers’ motivation to learn in predicting teachers’ OPD engagement (e.g., whether the perception of high PD quality can compensate for low motivation to learn; RQ3), we evaluated the interaction effects of the latent moderated structural equations (M5.1 to M5.12 shown in Tables 7, 8, 9 and 10). Overall, we found compensatory effects between OPD quality characteristics and teachers’ motivation to learn. However, for the three dimensions of OPD engagement, different OPD quality characteristics showed compensatory effects for low teacher motivation to learn. First, regarding teachers’ behavioral engagement, collaboration was a compensatory OPD quality characteristic for teachers’ low motivation to learn (interaction effect: β = −0.26, p < 0.001; see M5.10 in Table 10). Second, regarding teachers’ affective engagement, clarity and structure (interaction effect: β = −0.36, p < 0.001; see M5.2 in Table 7), practical relevance (interaction effect: β = −0.28, p < 0.001; see M5.5 in Table 8), and cognitive activation (interaction effect: β = −0.25, p < 0.001; see M5.8 in Table 9) were shown to be compensatory OPD quality characteristics for teachers’ low motivation to learn. Finally, regarding teachers’ cognitive engagement, the level of cognitive activation was shown to be a compensatory OPD quality characteristic for teachers’ low motivation to learn (interaction effect: β = −0.16, p = 0.001; see M5.9 in Table 9).

4 Discussion

The study aimed to investigate the interplay between the quality of online professional development (OPD) and teachers’ motivation to learn in relation to teachers’ engagement in OPD. A sample of 593 teachers who participated in an OPD program was analyzed to address the research questions. The study’s results provide valuable insights into the factors influencing teachers’ engagement in OPD. First, the perceived quality of OPD was positively associated with teachers’ engagement. This finding supports previous research highlighting the importance of quality characteristics for effective (O)PD, such as clarity and structure, coherence, active learning, and collaboration. The study adds to the literature by demonstrating that these quality characteristics also apply to OPD, emphasizing the need for well-designed online programs that align with teachers’ professional needs. However, based on the study, no conclusion can be drawn on how exactly an OPD program should be designed because OPD quality refers to a specific selection of generic characteristics (i.e., cross-OPD program characteristics mentioned in widely cited models like by Desimone (2009) or Darling-Hammond et al. (2017)) but not to the effectiveness of individual program components.

Second, teachers’ motivation to learn was positively associated with their engagement in OPD. This finding aligns with previous research emphasizing the role of intrinsic motivation and personal interest in driving teachers’ participation and engagement in (O)PD. Teachers motivated to learn and saw value in the OPD content were more likely to actively engage in the learning process, invest effort, and apply the acquired knowledge to their professional practice. However, the results should be interpreted against the background that we only covered a certain selection of influencing variables on teachers’ engagement in OPD (i.e., context or further participants’ characteristics are not covered; see Fig. 1).

Furthermore, the study explored the interaction between OPD quality and teachers’ motivation to learn. The results indicated that the combined effect of OPD quality and motivation was more than additive. Two potential scenarios were considered: a synergistic effect and a compensatory effect. The findings revealed a compensatory effect, indicating that the perception of high OPD quality can compensate for low motivation to learn. This finding highlights the importance of addressing OPD quality to maximize the engagement and effectiveness of OPD initiatives.

4.1 Limitations and future directions

Whereas this study contributes valuable insights into the relationship between the quality of OPD, teachers’ motivation, and their engagement, several limitations should be considered, some of which also provide directions for future research in the field of OPD.

Firstly, the study design employed a cross-sectional approach, which limits our ability to establish causal relationships between OPD quality, motivation, and engagement. The study’s cross-sectional nature implies that we can examine these factors at only a single point in time without capturing potential changes or fluctuations over time. To overcome this limitation, future research could adopt longitudinal designs to explore the dynamic nature of engagement and better understand how OPD quality and motivation influence teachers’ engagement over an extended period. Moreover, longitudinal studies can provide insights into the long-term effects of OPD on teachers’ professional growth. In addition, by adopting a longitudinal approach, researchers can better understand the causal relationships and potential reciprocal effects between OPD quality, motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes.

Another limitation of this study is the presence of missing values. Although state-of-the-art techniques were employed to handle missing data, such as full information maximum likelihood, it is important to acknowledge that missing values may introduce bias and affect the generalizability of the findings. The extent and pattern of missing data should be carefully considered when interpreting the results. Future research should strive to minimize missing data through rigorous data collection procedures to enhance the robustness and representativeness of the findings.

Additionally, the study relied on self-report measures subject to certain limitations. Whereas self-report measures provide valuable insights into teachers’ perceptions and experiences, they introduce the possibility of response biases, such as social desirability bias, where participants may provide answers they perceive as more socially acceptable. This may affect the accuracy and reliability of the reported levels of engagement, OPD quality, and motivation. Although efforts were made to ensure confidentiality and anonymity, it is important to consider potential biases associated with self-report measures. Future research should employ mixed methods approaches to complement self-report measures to enhance the validity and reliability of the findings. Integrating objective measures, such as observational data or learning artifacts, can provide a more comprehensive understanding of teachers’ engagement and the actual impact of OPD on their instructional practices. Triangulating different data sources can strengthen the validity and reliability of research findings.

Furthermore, researchers should explore the moderating and mediating factors influencing the relationship between OPD quality, motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes. Teachers’ prior knowledge, experience, and context-specific characteristics may interact with OPD quality and motivation to influence engagement and learning outcomes. Understanding these factors can inform the development of tailored OPD interventions and enhance their effectiveness.

On a positive note, a strength of this study is the random sampling approach employed to select participants from the population of OPD. This random sampling technique increases the likelihood of obtaining a representative sample and enhances the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of teachers engaging in OPD. The random sample allows for more robust inferences and strengthens the study’s external validity. However, it is important to acknowledge that even with a random sample, there may still be specific characteristics or factors that differ between the sample and the broader population. Future research could further diversify the sample by including teachers from different geographic regions, grade levels, and subject areas to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the relationship between OPD quality, motivation, and engagement.

Lastly, a limitation of this study is the absence of direct measurement of teachers’ learning outcomes. Whereas the study focused on teachers’ engagement in OPD, it did not assess the impact of OPD on teachers’ knowledge, skills, or instructional practices. Learning outcomes are important to PD effectiveness and should be considered in future research. That is, if future research examines the relationship between OPD quality, motivation, engagement, and learning outcomes (i.e., changes in instructional practices, overall professional growth, and student outcomes), researchers can better understand the mechanisms underlying effective PD. Furthermore, researchers can provide evidence-based insights into the effectiveness of different OPD approaches and inform the design of future interventions.

4.2 Implications for practice

The findings of this study have several important implications for practice in the field of OPD for teachers. Firstly, the study highlights the significance of ensuring high-quality OPD programs for teachers. Practitioners should prioritize developing and implementing OPD initiatives designed to meet teachers’ specific needs, provide relevant and up-to-date content, and incorporate interactive and engaging learning activities. By investing in the quality of OPD programs, educational institutions and policymakers can enhance teachers’ motivation and engagement, which may lead to more effective professional growth and improved instructional practices in the classroom.

Secondly, the study underscores the importance of fostering intrinsic motivation among teachers. Practitioners should create a supportive and empowering learning environment that nurtures teachers’ sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Providing opportunities for self-directed learning, collaborative activities, and meaningful feedback can enhance teachers’ intrinsic motivation and promote their active engagement in OPD. Additionally, recognizing and rewarding teachers’ achievements and progress can further strengthen their motivation and commitment to ongoing professional development. Furthermore, the findings suggest that practitioners should consider the role of social support in promoting teachers’ engagement in OPD. Building communities of practice or facilitating peer collaboration and networking opportunities can create a sense of belongingness and shared learning experiences. Practitioners should leverage technology to facilitate online forums, discussion boards, and virtual communities where teachers can exchange ideas, seek advice, and share their experiences. By fostering a supportive social environment, practitioners can enhance teachers’ engagement in OPD and create opportunities for collaborative professional growth.

Notes

(O)PD means both face-to-face and online PD. We use OPD when utterances refer exclusively to online professional development and face-to-face PD when utterances refer exclusively to face-to-face professional development.

This statistic is based on 50 imputed data sets.

References

Antoniou, P., & Kyriakides, L. (2013). A dynamic integrated approach to teacher professional development: Impact and sustainability of the effects on improving teacher behaviour and student outcomes. Teaching and Teacher Education, 29, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2012.08.001.

Appova, A., & Arbaugh, F. (2018). Teachers’ motivation to learn: Implications for supporting professional growth. Professional Development in Education, 44(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2017.1280524.

Bareis, A., Fütterer, T., Spengler, M., Trautwein, U., Nagengast, B., Krammer, G., Boxhofer, E., Nausner, E., Pflanzl, B., & Mayr, J. (2023). Interest is a stronger predictor than conscientiousness for teachers’ intensity in engaging in professional development. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Bates, M. S., Phalen, L., & Moran, C. (2016). Online professional development: a primer. Phi Delta Kappan, 97(5), 70–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/0031721716629662.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 57(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.2307/2346101.

Bragg, L. A., Walsh, C., & Heyeres, M. (2021). Successful design and delivery of online professional development for teachers: a systematic review of the literature. Computers & Education, 166, 104158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104158.

van Buuren, S. (2018). Flexible imputation of missing data (2nd edn.). CRC Press.

van Buuren, S., & Groothuis-Oudshoorn, K. (2011). mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45(3), 1–67. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v045.i03.

Chan, S., Maneewan, S., & Koul, R. (2021). Teacher educators’ teaching styles: relation with learning motivation and academic engagement in pre-service teachers. Teaching in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1947226.

Chi, M. T. H., & Wylie, R. (2014). The ICAP framework: linking cognitive engagement to active learning outcomes. Educational Psychologist, 49(4), 219–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.965823.

Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd edn.). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Darling-Hammond, L., Wei, R. C., Andree, A., Richardson, N., & Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional learning in the learning profession. A status report on teacher development in the United States and abroad. Stanford: National Staff Development Council and The School Redesign Network at Stanford University.

Darling-Hammond, L., Hyler, M. E., & Gardner, M. (2017). Effective teacher professional development. Learning Policy Institute.

Decker, A.-T., Kunter, M., & Voss, T. (2015). The relationship between quality of discourse during teacher induction classes and beginning teachers’ beliefs. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 30(1), 41–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-014-0227-4.

Dede, C., Jass Ketelhut, D., Whitehouse, P., Breit, L., & McCloskey, E. M. (2009). A research agenda for online teacher professional development. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108327554.

Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational Researcher, 38(3), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140.

Fishman, B. J. (2016). Possible futures for online teacher professional development. In C. Dede, A. Eisenkraft, K. Frumin & A. Hartley (Eds.), Teacher learning in the digital age. Online professional development in STEM education (pp. 3–31). Harvard: Education Press.

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59–109. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059.

Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M., & Lawson, M. A. (2016). Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learning and Instruction, 43, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.002.

Fredricks, J. A., Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2019). Interventions for student engagement: overview and state of the field. In Handbook of student engagement interventions (pp. 1–11). Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-813413-9.00001-2.

Fütterer, T., Hübner, N., Fischer, C., & Stürmer, K. (2023a). Heading for new shores? Longitudinal participation patterns in teacher professional development. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Fütterer, T., Scherer, R., Scheiter, K., Stürmer, K., & Lachner, A. (2023b). Will, skills, or conscientiousness: What predicts teachers’ intentions to participate in technology-related professional development? Computers & Education, 198, 104756. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104756.

Gorges, J., Maehler, D. B., Koch, T., & Offerhaus, J. (2016). Who likes to learn new things: measuring adult motivation to learn with PIAAC data from 21 countries. Large-Scale Assessments in Education, 4(1), 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40536-016-0024-4.

Graham, J. W. (2003). Adding missing-data-relevant variables to FIML-based structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 10(1), 80–100. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1001_4.

Graham, J. W. (2012). Missing data. Analysis and design. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-4018-5.

Harper-Hill, K., Beamish, W., Hay, S., Whelan, M., Kerr, J., Zelenko, O., & Villalba, C. (2022). Teacher engagement in professional learning: what makes the difference to teacher practice? Studies in Continuing Education, 44(1), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2020.1781611.

Hauk, D., Gröschner, A., Weil, M., Böheim, R., Schindler, A.-K., Alles, M., & Seidel, T. (2022). How is the design of teacher professional development related to teacher learning about classroom discourse? Findings from a one-year intervention study. Journal of Education for Teaching. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2022.2152315.

Hayes, T. (2021). R‑squared change in structural equation models with latent variables and missing data. Behavior Research Methods, 53(5), 2127–2157. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-020-01532-y.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Jansen in de Wal, J., den Brok, P. J., Hooijer, J. G., Martens, R. L., & van den Beemt, A. (2014). Teachers’ engagement in professional learning: Exploring motivational profiles. Learning and Individual Differences, 36, 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.08.001.

Ji, Y. (2021). Does teacher engagement matter? Exploring relationship between teachers’ engagement in professional development and teaching practice. International Journal of TESOL Studies, 3(4), 42–60. https://doi.org/10.46451/ijts.2021.12.04.

Jorgensen, T. D., Pornprasertmanit, S., Schoemann, A. M., & Rosseel, Y. (2022). semTools: Useful tools for structural equation modeling (R package version 0.5-6). https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=semTools Computer software.

Klassen, R. M., Yerdelen, S., & Durksen, T. L. (2013). Measuring teacher engagement: development of the engaged teachers scale (ETS). Frontline Learning Research, 1(2), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v1i2.44.

Kleickmann, T., Tröbst, S., Jonen, A., Vehmeyer, J., & Möller, K. (2016). The effects of expert scaffolding in elementary science professional development on teachers’ beliefs and motivations, instructional practices, and student achievement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(1), 21–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000041.

Kleiman, G. M., & Wolf, M. A. (2016). Going to scale with online professional development: the friday institute MOOcs for educators (MOOC-Ed) initiative. In C. Dede, A. Eisenkraft, K. Frumin & A. Hartley (Eds.), Teacher learning in the digital age: Online professional development in STEM education (pp. 49–68). Harvard: Education Press.

Klein, A., & Moosbrugger, H. (2000). Maximum likelihood estimation of latent interaction effects with the LMS method. Psychometrika, 65(4), 457–474. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296338.

Klieme, E., Pauli, C., & Reusser, K. (2009). The pythagoras study: investigating effects of teaching and learning in swiss and german mathematics classrooms. In T. Janík & T. Seidel (Eds.), The power of video studies in investigating teaching and learning in the classroom (pp. 137–160). Münster: Waxmann.

Landry, S. H., Anthony, J. L., Swank, P. R., & Monseque-Bailey, P. (2009). Effectiveness of comprehensive professional development for teachers of at-risk preschoolers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(2), 448–465. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013842.

Lee, T., & Shi, D. (2021). A comparison of full information maximum likelihood and multiple imputation in structural equation modeling with missing data. Psychological Methods, 26(4), 466–485. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000381.

Lipowsky, F., & Rzejak, D. (2015). Key features of effective professional development programmes for teachers. Ricercazione, 7(2), 27–51.

Masuda, A. M., Ebersole, M. M., & Barrett, D. (2013). A qualitative inquiry: teachers’ attitudes and willingness to engage in professional development experiences at different career stages. International Journal for Professional Educators, 79(2), 6–14.

McNeish, D., & Wolf, M. G. (2021). Dynamic fit index cutoffs for confirmatory factor analysis models. Psychological Methods. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000425.

McNeish, D., Stapleton, L. M., & Silverman, R. D. (2017). On the unnecessary ubiquity of hierarchical linear modeling. Psychological Methods, 22(1), 114–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000078.

Meyer, A., Kleinknecht, M., & Richter, D. (2023). What makes online professional development effective? The effect of quality characteristics on teachers’ satisfaction and changes in their professional practices. Computers & Education, 200, 104805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2023.104805.

Morina, F., Fütterer, T., Hübner, N., Zitzmann, S., & Fischer, C. (2023). Effects of online teacher professional development on the teacher, classroom, and student level: a meta-analysis. Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/3yaef. Preprint

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998). Mplus user’s guide (8th edn.). Muthén & Muthén.

Osman, D. J., & Warner, J. R. (2020). Measuring teacher motivation: the missing link between professional development and practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 92, 103064. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2020.103064.

Penuel, W. R., Fishman, B. J., Yamaguchi, R., & Gallagher, L. P. (2007). What makes professional development effective? Strategies that foster curriculum implementation. American Educational Research Journal, 44(4), 921–958. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831207308221.

Pintrich, P. R., Smith, D. A. F., Duncan, T., & Mckeachie, W. J. (1991). A manual for the use of the motivated strategies for learning questionaire (MSLQ)

Posit team (2023). Rstudio: integrated development for R. http://www.posit.co/ [Computer software]. Posit Software, PBC.

Powell, C. G., & Bodur, Y. (2019). Teachers’ perceptions of an online professional development experience: implications for a design and implementation framework. Teaching and Teacher Education, 77, 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.09.004.

Praetorius, A.-K., Klieme, E., Herbert, B., & Pinger, P. (2018). Generic dimensions of teaching quality: the German framework of three basic dimensions. ZDM, 50(3), 407–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-018-0918-4.

Quinn, F., Charteris, J., Adlington, R., Rizk, N., Fletcher, P., Reyes, V., & Parkes, M. (2019). Developing, situating and evaluating effective online professional learning and development: a review of some theoretical and policy frameworks. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(3), 405–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-018-00297-w.

R Core Team (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org

Richter, E., & Richter, D. (2023). Fortbildungsmonitor. Ein Instrument zur Erfassung der Prozessqualität von Lehrkräftefortbildungen. Potsdam. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:27640.

Richter, E., & Richter, D. (2024). Measuring the quality of teacher professional development—A large-scale validation study of an 18-items instrument for daily use. Open Science Framework. https://doi.org/10.31219/osf.io/qr4t5.

Richter, D., Kleinknecht, M., & Gröschner, A. (2019). What motivates teachers to participate in professional development? An empirical investigation of motivational orientations and the uptake of formal learning opportunities. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102929. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102929.

Richter, E., Marx, A., Huang, Y., & Richter, D. (2020). Zeiten zum beruflichen Lernen: Eine empirische Untersuchung zum Zeitpunkt und der Dauer von Fortbildungsangeboten für Lehrkräfte. Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, 23(1), 145–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-019-00924-x.

Richter, E., Kunter, M., Marx, A., & Richter, D. (2021). Who participates in content-focused teacher professional development? Evidence from a large scale study. Frontiers in Education, 6, 722169. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.722169.

Richter, E., Fütterer, T., Meyer, A., Eisenkraft, E., & Fischer, C. (2022). Teacher collaboration and professional learning: Examining professional development during a national education reform. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 68(6), 798–819. https://doi.org/10.3262/ZP2206798.

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: an R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

Rzejak, D., Künsting, J., Lipowsky, F., Fischer, E., Dezhgahi, U., & Reichardt, A. (2014). Facetten der Lehrerfortbildungsmotivation – eine faktorenanalytische Betrachtung. Journal for educational research online, 6(1), 139–159.

Seidel, T., & Shavelson, R. J. (2007). Teaching effectiveness research in the past decade: the role of theory and research design in disentangling meta-analysis results. Review of Educational Research, 77(4), 454–499. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654307310317.

Taber, K. S. (2018). The use of Cronbach’s Alpha when developing and reporting research instruments in science education. Research in Science Education, 48(6), 1273–1296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-016-9602-2.

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., & Fung, I. (2007). Teacher professional learning and development: Best evidence synthesis iteration (BES). Ministry of Education.

Trautwein, U., Lüdtke, O., Nagy, N., Lenski, A., Niggli, A., & Schnyder, I. (2015). Using individual interest and conscientiousness to predict academic effort: Additive, synergistic, or compensatory effects? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(1), 142–162. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000034.

Wigfield, A., & Eccles, J. S. (2000). Expectancy–value theory of achievement motivation. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 68–81. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1015.

Wolf, M. G., & McNeish, D. (2022). dynamic: DFI Cutoffs for Latent Variable Models. R package version 1.1.0. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dynamic

Zhang, S., & Liu, Q. (2019). Investigating the relationships among teachers’ motivational beliefs, motivational regulation, and their learning engagement in online professional learning communities. Computers & Education, 134, 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.02.013.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Postdoctoral Academy of Education Sciences and Psychology of the Hector Research Institute of Education Sciences and Psychology, Tübingen, funded by the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of Science, Research, and the Arts. The data collection was conducted in a study funded by the Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

T. Fütterer, E. Richter and D. Richter declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The research was approved by the Ministerium für Schule und Bildung des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen. The authors are responsible for the content of this publication.

Appendices

Appendix A

1.1 Items used to measure teachers’ engagement in PD, perceived PD quality, and motivation to learn

Appendix B

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fütterer, T., Richter, E. & Richter, D. Teachers’ engagement in online professional development—The interplay of online professional development quality and teacher motivation. Z Erziehungswiss 27, 739–768 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-024-01241-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-024-01241-8