Abstract

In this study we investigated the amount of social capital as well as its effect on subjective well-being for the whole Austrian population and separately for rural- and urban areas. By using the Austrian Social Survey 2018, we were able to analyze various social capital dimensions based on a conceptual model developed by Kawachi (2008), namely informal and formal social capital, social support as well as social and institutional trust. We observed differences between rural and urban areas in the social-capital dimension of informal social capital: Individuals in rural areas report more contacts with lower-skilled vocations and more family contacts while individuals from urban areas report more social participation and more contact with a close friend. For the Austrian population as a whole, more contacts with highly educated professions, frequent contact (at least several times a week) with a close friend, as well as social and institutional trust, foster subjective well-being. Frequent contact with up to three distinct family members fosters subjective well-being for the entire Austrian sample as well as for individuals living in rural-, but not in urban areas. This study extends previous research by showing different amounts of informal social capital between urban and rural areas as well as different effects on subjective well-being. To summarize, our results confirm the beneficial influence of certain social capital dimensions on subjective well-being in Austria taking into account control variables based on previous research, while showing different patterns and effects of informal social capital between urban and rural areas.

Zusammenfassung

In dieser Studie untersuchten wir die Höhe des Sozialkapitals sowie dessen Auswirkungen auf das subjektive Wohlbefinden in der gesamten österreichischen Bevölkerung sowie geschichtet in ländlichen und städtischen Gebieten. Mithilfe des Sozialen Survey Österreich (SSÖ) 2018 konnten wir auf der Grundlage einer Konzeption von Kawachi (2008) verschiedene Dimensionen des Sozialkapitals analysieren, nämlich informelles und formales Sozialkapital, soziale Unterstützung sowie soziales und institutionelles Vertrauen. Wir haben Unterschiede zwischen ländlichen und städtischen Gebieten in der Sozialkapital-Dimension des informellen Sozialkapitals beobachtet: Personen in ländlichen Gebieten berichten von mehr Bekanntschaften mit gering ausgebildeten Berufen und mehr Familienkontakten, während Personen aus städtischen Gebieten von mehr sozialer Partizipation und mehr Kontakten mit einem engen Freund berichten. Für die gesamte österreichische Bevölkerung fördern mehr Bekanntschaften mit hoch ausgebildeten Berufen, häufige (mindestens mehrmals pro Woche) Kontakte zu einem engen Freund sowie soziales und institutionelles Vertrauen das subjektive Wohlbefinden. Der häufige Kontakt mit bis zu drei verschiedenen Familienmitgliedern fördert das subjektive Wohlbefinden der gesamten österreichischen Stichprobe sowie der Menschen, die in ländlichen, nicht aber in städtischen Gebieten leben. Diese Studie erweitert die bisherige Forschung, indem sie differenzierte Unterschiede an informellem Sozialkapital zwischen städtischen und ländlichen Gebieten sowie unterschiedliche Auswirkungen auf das subjektive Wohlbefinden aufzeigt. Zusammenfassend bestätigen unsere Ergebnisse den positiven Einfluss bestimmter Sozialkapitaldimensionen auf das subjektive Wohlbefinden in Österreich unter Berücksichtigung von Kontrollvariablen auf der Grundlage früherer Untersuchungen und sie zeigen unterschiedliche Muster und Auswirkungen des informellen Sozialkapitals zwischen städtischen und ländlichen Gebieten.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The present study deals with social capital in urban and rural regions of Austria and its impact on individual well-being as a subjective indicator for quality of life. While there may be little dispute that a high quality of life for its members is one of the most important goals of any society, the question of what quality of life is, is more difficult to answer. Traditionally, the gross domestic income of a country was considered as the major indicator for high quality of life (Oishi and Schimmack 2010). This economic view relies on the assumption that higher prosperity automatically leads to higher utility. Today, more and more researchers, politicians and global organizations such as the OECD, take a more elaborate path and complement objective macro data with subjective indicators, mainly collected through surveys, to measure quality of life (Diener et al. 2015). The most prominent subjective indicator for this purpose is subjective well-being (see Oishi and Schimmack 2010), which is considered to be composed by several dimensions such as positive affect, the lack of negative affect, happiness or life satisfaction (e.g. Diener et al. 2002).

Previous research has identified many factors that promote subjective well-being, e.g. the family status (being married), financial resources, etc. (see Dolan et al. 2008). Furthermore, social resources have proven to be key drivers for high subjective well-being (e.g. Helliwell and Putnam 2004). Different dimensions of social resources can be summarized in the concept of “social capital” which was first systematically analyzed by Bourdieu (1986), who described social capital as the individual resources that one receives from the possession of a durable network. Since then social capital has evolved into a multidimensional construct (see van Oorschot and Arts 2005). While Coleman (1990) defines social capital by its function to facilitate certain actions of actors whether persons or corporate actors within a social structure, Putnam (1993) clearly highlights the collective character of social capital which he describes as features of social organizations, such as networks, norms, and trust (see Portes 1998). The different theoretical definitions of social capital (see Bjørnskov and Sønderskov 2013) also lead to different conceptions of operationalization in empirical studies that are difficult to compare.

In line with the definition of social capital from Bourdieu (1986), in this paper we focus our analyses on several dimensions of social resources and follow the classification of social capital by Kawachi (2008) which combines different dimensions of social resources in a structural and a cognitive component of individual social capital. The classification will be described further below.

Using the Austrian Social Survey (Sozialer Survey Österreich) 2018 as the data source for the present study, allows a comprehensive analysis of social capital and subjective well-being. Therefore, this study aims first at describing the extent of different dimensions of social capital and subjective well-being in the Austrian population and second investigating the effects of different dimensions of social capital on subjective well-being. Social capital, however, is not equally distributed across regions. Classical sociological theories argue that rural areas show higher social embeddedness, leading to close social networks while urban areas are characterized by low frequency and intimacy of social contacts (Durkheim 1893 [1997]; Goode 1970). Evidence from previous research indicates more bonding social capital in rural areas, referring to strong and close social ties, as well as more frequent family-based social relations (Sørensen 2016; Hofferth and Iceland 1998). Therefore, our study’s third aim is to investigate differences in the amounts of social capital and the relationship between social capital and well-being in rural and urban areas.

In order to pursue these research goals, we first present our theoretical background for the relation between social resources and subjective well-being. Since well-being can be considered as part of one’s health based on the bio-psycho-social model (see Deep 1999), we will not only review theories regarding the beneficial impact of social capital on well-being, but also theories regarding its positive impact on health.Footnote 1 Subsequently, we introduce the concept of social capital as a classification for social resources before reviewing recent literature in this research field. Additionally, we will briefly review the literature regarding social capital and subjective well-being in urban and rural areas before we present our methods, results and discussion of this study.

1.1 Social resources and well-being

According to resource-oriented approaches in health psychology and sociology such as the salutogenic model (Antonovsky 1979), individuals need internal as well as external (social) resources to cope with (daily) stressors and thus maintain health and well-being. On a fundamental level, the need to belong theory additionally argues that individuals have the innate urge for social contacts, whereas social deprivation leads to temporary higher stress and thus temporary lower well-being but also to long lasting negative effects on well-being (see Baumeister and Leary 1995). Social needs also play a crucial part in the “hierarchy of needs” model by Maslow (see McLeod 2007), a motivation theory with a focus on intrinsic desires apart from external rewards. The most widespread version of this theoretical model includes five hierarchically arranged needs, which have to be fulfilled step by step. Social needs, and thus belongingness as well as affection and love, are one of those needs, which gain importance after basic physiological needs (e.g. food, sleep, shelter) as well as safety needs (e.g. emotional and financial security) are met. Taking all theories together, this clearly points to a crucial role of social resources for one’s individual well-being.

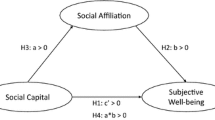

To differentiate between different dimensions of social resources, we refer to the concept of social capital. Besides its vague conceptualization (see Bjørnskov and Sønderskov 2013), social capital has proven to be a powerful concept in sociological and economic research, both on the individual- and societal level (e.g. Portes 1998; Putnam 1993). For this paper we follow the classification by Kawachi (2008). According to this concept, individual social capital is composed of a structural and a cognitive component. The actual social network (e.g. the size and intensity of contacts) represents the structural component, the subjective perception of one’s social resources is the cognitive component. Structural social capital can be further decomposed into informal relations—e.g. contact with family, friends and working colleagues; and formal relations—e.g. memberships in different groups. Cognitive social capital further includes perceived social support, trust in institutions and social trust (see Fig. 1). Structural and cognitive social capital are not independent from each other. The size of one’s social network influences the perception of social resources and vice versa (Gilbert et al. 2013).

Individual social capital based on Kawachi (2008)

Besides the general theories regarding social resources and well-being described above, multiple scholars proposed specific assumptions about the impact and pathways of social networks (structural social capital) as well as cognitive social capital on health and well-being. Berkman and Glass (2000) provide an overview about previous formulated theories regarding the impact of social networks on health and well-being. First, social networks provide social support, which works as a ‘buffer factor’ and subsequently decreases stress. Second, a vital social network can lead to conducive social norms that can motivate individuals to decrease detrimental behavior such as substance abuse while increasing healthy behavior, for example sports. Third, social networks stimulate social participation, which provides a sense of belonging to a social group and opportunities to learn new skills. Fourth, social networks provide tangible assistance, such as money, information about job opportunities, transportation, etc. and thus reduce the detrimental effects of stress. Cohen (2004) adds that social networks can foster positive psychological states (e.g. positive affect, stability or high self-esteem) and thus increase well-being. Social trust as part of cognitive social capital can increase health and well-being as it reflects generalized reciprocity. “I’ll do this for you now, without expecting anything immediately in return and perhaps without even knowing you, confident that down the road you or someone else will return the favor” (Putnam 2001). High social trust acts as a glue that can bind together societies and foster social cohesion (Delhey et al. 2018). Another theoretical position argues that high social trust is associated with reduced social anxiety, which subsequently leads to a lower stress level (Abbott and Freeth 2008). Institutional trust on the other hand is conceptually distinct from social trust as it includes trust in governments, political authorities or other social institutions. High institutional trust can foster well-being as a subjective measure of the quality of regional institutions, preventing individuals from feeling powerless and helpless within the society (Kroll 2008).

1.2 Social resources and subjective well-being: Empirical evidence

The above-mentioned theoretical assumptions concerning the relations of social capital and well-being have extensive empirical support. Helliwell and Putnam (2004) reported positive relations between informal social contacts (friends, family, neighbors) as well as formal social contacts (organizational membership) and subjective well-being in the US and Canada. Portela et al. (2013) found positive relations between social as well as formal networks and subjective well-being in Europe. Calvo et al. (2012) further found a positive effect of social support on subjective well-being drawing from the Gallup World Poll, a dataset including 142 countries around the world. Fernandez and Muckenhuber (2019) additionally found a positive relation between social support and subjective well-being in Austria whereas Siedlecki et al. (2014) reported a positive effect of social support on subjective well-being based on a US sample. Social trust especially gained prominence as a robust and strong predictor for high subjective well-being on the individual (e.g. Calvo et al. 2012; Helliwell and Putnam 2004; Portela et al. 2013), but also on the aggregate level between countries (e.g. Glatz and Eder 2019; Mikucka et al. 2017). Previous studies obtained the same pattern for institutional trust, showing that institutional trust has a positive effect on subjective well-being (e.g. Portela et al. 2013; Puntscher et al. 2015).

While evidence for the positive influence of social capital on subjective well-being, in general, is well documented in the literature, the role of urban-rural differences for social capital is less clear. Sørensen (2016) argues that the widespread assumption of rural areas having more social capital than urban areas only applies to a certain extent. Empirical evidence in previous literature is mixed depending on different indicators for social capital and urbanization (for a review see Sørensen 2012). Following the definition of Putnam (2001), Sørensen (2016) distinguishes bonding and bridging social capital. While bonding social capital is described as (exclusive inward-looking) intra-community social capital, bridging social capital represents (inclusive outward-looking) extra-community social capital. Arguing bonding social capital should be higher in rural areas while bridging social capital should be higher in urban areas, Sørensen’s (2016) results drawn from a Danish survey indicate strong support for the first assumption of higher bonding social capital in rural areas but only some support for the second assumption of higher bridging social capital in urban areas. One explanation of more bonding social capital in rural areas could be the need for more cooperation due to less availability of institutional support services. Moreover, as rural areas are characterized by smaller group sizes, this could lead to a bigger incentive to maintain good and loyal connections with peers. In smaller communities, a breach of trust would be communicated quickly to the rest of the community members and thus it is more likely that social sanctions such as social exclusion would follow (Sørensen 2016). Further evidence for more (bonding) social capital in rural areas was provided by Hofferth and Iceland (1998) who found (by using data from a national sample of U. S. households) that families in rural areas are more likely to interact exclusively with kin than families in urban areas, supporting the notion that family ties are stronger in rural areas where families are less mobile and more strongly connected to their kin networks.

Besides different amounts of social capital between urban and rural areas, only a few studies so far tested and compared differences in the strength of the effect of social capital on subjective well-being in rural and urban areas. By using data from an U. S. survey, Mair and Thivierge-Rikard (2010) found evidence that the positive effect of informal strong ties (such as visiting with friends, neighbors, or relatives) on subjective well-being is stronger for rural older adults than urban. The reason for these different effects could be different expectations regarding social interactions. Rural individuals might expect more informal, strong social interactions than urban individuals. This expectation of more informal strong ties may also reflect a rural cultural norm (see Mair and Thievierge-Rikard 2010). Results of a study by Tobiasz-Adamczyk and Zawisza (2017) with data from Poland did not yield clear evidence of different effects in urban and rural areas of social capital on subjective well-being since results for different regions in Poland were mixed. Both studies mentioned above only investigated samples of older adults. Ziersch et al. (2009) investigated relationships between social capital and health using a sample of the population in South Australia. They found that social capital and its relationship to health differed for participants in rural and urban areas. Higher levels of social capital were significantly associated with better mental health for both urban and rural participants, but with better physical health only for urban participants. Unfortunately, in regard to our study, Ziersch et al. (2009) only investigated effects on health and not on subjective well-being. Liu et al. (2014) found positive effects of social support on psychological well-being both for rural and urban regions in China. Their results also indicate protective functions of social support as it buffers the negative effect of increasing health-care expenditure on psychological well-being, but only among rural residents. Their results also indicate that in rural areas more social support strengthens psychological well-being during social change. To sum up, evidence on different effects of social capital on subjective well-being in rural and urban areas is sparse and mixed. Therefore, we investigate whether differences in the strength of the effect can be found in the sample of the Austrian Social Survey 2018.

Previous studies which investigated levels of social capital already showed that the Austrian population, at least in the past, is able to rely on a high level of social resources. Using the Austrian Social Survey 2016, Fernandez and Muckenhuber (2019) showed that more than half of the Austrian population can rely on social support in various life situations while Kmet and Weicht (2019) showed that 60–80% of the Austrian population (highly) values family and friends. By analyzing trends in social capital, subjective well-being and more, the European Quality of Life survey shows that around 60% of the Austrian population reports contact with friends or neighbors almost every day while around half of the population reports trust in other people (social trust), which is average compared to the European Union. Regarding subjective well-being, the Austrian population shows higher values than the EU average with life satisfaction/happiness scores around 80 on a 0–100 scale compared to the EU average of around 70 (Delhey et al. 2018).

Since previous studies provide a strong theoretical background as well as empirical support for a positive effect of social capital on subjective well-being, we investigate the amount of social capital as well as its effect on subjective well-being amongst the Austrian population as a whole, and separately for urban and rural areas. Although previous research indicates certain levels of social capital and subjective well-being in Austria, we cannot formulate specific hypotheses for this purpose as time influences those levels and since item wordings and scales vary between studies.

We use the Austrian Social Survey 2018 as it provides extensive items to measure informal and formal social capital (social networks), social and institutional trust, and perceived social support as well as items to measure subjective well-being. Our analyses are led by the following research questions:

How do Austrians perceive their well-being and the extent of different dimensions of social capital?

Are there differences regarding subjective well-being and social capital between urban and rural areas in Austria?

H1: Rural areas report higher amounts of informal social capital

How do different dimensions of social capital affect subjective well-being?

Does social capital affect subjective well-being differently in urban- compared to rural areas?

H2: Informal social capital shows a stronger effect on subjective well-being in rural areas

2 Methods

2.1 Data

The database for our analyses is the ‘Sozialer Survey Österreich’ (Austrian Social Survey) 2018, which consists of a random sample of 1200 Austrians representative for the national population aged 18 and above. The survey was conducted with computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPI) during the second quarter of 2018. The response rate reached 51%. The dataset, as well as the method report with an elaborate description of the sample, can be found at AUSSDA—The Austrian Social Survey Data Archive (Hadler et al. 2019). To use the best representation of the Austrian population, we use a post-stratification plus design-weight for descriptive statistics.

2.2 Variables

In the following, we will describe the relevant variables for this study. Besides the original scale, we rescaled every single item from 0 to 100 for descriptive results such that higher scores represent higher amounts of social capital and well-being. We will present Cronbach’s α estimations for reflexive scales.

2.2.1 Structural (informal) social capital

-

1.

Contacts with high- and low educated workers

To measure contacts with various occupations as part of informal social capital, participants were asked if they … “know a woman or a man who is …? a.) a bus/lorry driver, b.) a senior executive of a large company, c.) a home or office cleaner, d.) a hairdresser/barber, e.) a human resource manager/personnel manager, f.) a lawyer, g.) a car mechanic, h.) a nurse, i.) a police officer, j.) a school teacher”; with the possible answers “Family or relative”, “Close friend”, “Someone else I know”, and “No one”.

Since jobs in this list differ in terms of required education, we distinguished two kinds of professional contacts, separating those jobs which require tertiary education from those jobs that do not. While having contacts whose occupations require less education include knowing a (wo)man who is a.) a bus/lorry driver, c.) a home or office cleaner, d.) a hairdresser/barber, g.) a car mechanic or i.) a police officer, having contacts whose occupations require higher education includes knowing a (wo)man who is b.) a senior executive of a large company, e.) a human resource manager/personnel manager, f.) a lawyer, h.) a nurse, or j.) a school teacher. We summed all answers wherein “1” indicates that participants know a woman or man in the respective profession.

- 2.

Contact frequency with family and friends

Several items asked, “Think about the person (…) you have contact with most frequently: How often do you have contact with this person, either face-to-face, by phone, internet or any other communication device?”. Participants were asked this question about “a parent”, “a brother or sister”, “an adult child”, “another family member besides their spouse or partner, parents, siblings or adult children” and “a close friend”.

Due to the non-linear scale, we first computed dummy variables that indicate if someone has contact with the respective friend or family member on a “Daily” or “Several times a week” basis, or if the respective friend or family member lives in the same household. All remaining answers (“Once a week” or fewer, as well as “I don’t have … [a sibling] etc.”, “[my parents] etc. are not alive anymore”) are transformed into “0”. The proportion of respondents who have contact with a given person at least several times a week ranges from 27% for “other relatives” to 40% for “adult child”. The answers for the four questions on contact with relatives were combined into an index for family contact, ranging from “0” (indicating no frequent contact with family members) to “4” (indicating frequent contact with all mentioned family members). Besides this indicator for family contact, the dummy variable “contact with a close friend” remains a dummy variable as explained above. Since variable calculations are arbitrary acts, we created alternative variables for “family contact” and “contact with a close friend” which additionally included contact “once a week”. We present findings with those alternative variables in the result section as well.

- 3.

Social participation

The survey includes one item asking, “How often do you go out to eat or drink with three or more friends or acquaintances who are not family members?” on a scale from “1” (daily) to “8” (never) to measure “social participation”. We transformed this item such that “8” indicates daily while “1” indicates never.

2.2.2 Structural (formal) social capital

To measure formal social capital, the survey asks … “In the past 12 months, how often, if at all, have you taken part in activities …? a.) of groups or associations for leisure, sports or culture? b.) of political parties, political groups or political associations? c.) of charitable or religious organizations that do voluntary work?”. We form one index consisting of those three group activities in which “1” indicates group participation of “once in the past year” or more often, resulting in an index ranging from “0” to “3”.

2.2.3 Cognitive social capital

-

1.

Perceived social support

To measure perceived social support, the Austrian social survey 2018 contains two sets of questions.

One question asks regarding personal problems/situations, namely “Who would you turn to first to … a.) help you with a household or a garden job that you can’t do yourself? b.) help you around your home if you were sick and had to stay in bed for a few days? c.) be there for you if you felt a bit down or depressed and wanted to talk about it? d.) give you advice about family problems? e.) enjoy a pleasant social occasion with?” Participants can answer these questions with “a close family member”, “a more distant family member”, “a close friend”, “a neighbor”, “someone I work with”, “someone else”, and “no one”. The second question reads “Who or where would you turn to first to … a.) help you if you needed to borrow a large sum of money? b.) help you if you needed to find a job? c.) help you with administrative problems or official paperwork? d.) help you if you needed to find a place to live? e.) look after you if you were seriously ill?”. Possible answers are “family members or close friends”, “other persons”, “private companies”, “public services”, “non-profit or religious organizations”, “other organizations”, “no person or organization”. From these ten items, we derived an index which ranges from 0 to 10 points (for each item 1 point was assigned if the respondent indicated a person or institution s/he would turn to). Thus, as long as the respective respondent does not answer “no one”, we count 1 point.Footnote 2

- 2.

Social and Institutional trust

The survey includes an item list to measure institutional trust asking, “How much confidence do you have in … a.) Parliament, b.) Business and industry, c.) Churches and religious organizations, d.) Courts and the legal system, e.) Schools and the educational system”. The scale ranges from “1” (complete confidence) to “5” (no confidence at all). From these items we computed a mean index (Cronbach’s α = 0.73).

The last measured aspect of social capital, social trust, was measured with a single item, namely “Generally speaking, would you say that people can be trusted or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?”, ranging from “1” (“People can almost always be trusted”) to “5” (“You almost always can’t be too careful in dealing with people”). For both aspects of trust, we rescaled all answers such that higher values represent higher trust.

2.2.4 Outcome variable

The survey includes three items to measure subjective well-being, namely life satisfaction (1 “completely satisfied” to 7 “completely unsatisfied”), happiness (1 “very happy” to 4 “not happy at all” and momentary well-being (“how do you feel at the moment?”; 1 “very good” to 5 “very bad”). Again, we rescaled every item such that higher values represent higher subjective well-being. We additionally calculated a mean index out of these three single items (Cronbach’s α = 0.82).

2.2.5 Urbanization variable

At the end of the interview, interviewers noted whether the participant lives …. a.) in a big city (over 100,000 residents), b.) on the edge or in a suburb of a big city, c.) in a bigger city (40,000 to 100,000 residents), d.) in a small or medium town (5000 to under 40,000 residents), e.) in a village or f.) in a single house or farm in the countryside.

Due to low case numbers and in accordance with Sørensen (2016), we recoded this question into three categories, namely “urban” (living in a big city or on the outskirts or in a suburb of a big city), “suburban” (living in a town/city with 5000 to 100,000 residents) and “rural” (living in a village or in a single house or farm in the country). Preliminary exploratory analyses showed that results for suburban areas typically lie between the results for urban and rural areas. Therefore, we will only present the results for urban and rural areas.

2.2.6 Control variables

In accordance with previous research in this field (i.e. Helliwell and Putnam 2004; Portela et al. 2013), we control for sex, age, education, marriage, personal income, place of residence, unemployment, and church attendance. We use dummy variables to measure sex (1 = female), education (primary education or below, secondary education [“Matura”] and tertiary education), marriage (1 = married), place of residence (urban, suburban, rural) and unemployment (1 = unemployed). We also use dummy variables to measure age to consider non-linear effects (categories: ages 18–29, ages 30–44, ages 45–59, ages 60–74 and ages 75–95). Personal income is measured in quintiles (1–5) while church attendance is measured on a scale from “1” (Never) to “8” (several times a week).

2.3 Analytic strategy

First, we present descriptive results for social capital variables as well as for subjective well-being variables for the entire sample as well as for urban and rural areas. By using variance analysis, we analyze how urban and rural areas differ in terms of social capital and subjective well-being. For the multivariate analysis, we first used multilevel modelling which allows us to control for potential interviewer effects on the second level since a total of 75 interviewers conducted this survey (see Beullens and Loosveldt 2016). The analysis showed that 13.4% of the variation of subjective well-being is due to interviewer effects. However, a simple multiple regression analysis shows similar effects of social capital variables on subjective well-being and allows us to present standardized β coefficients (see Hox et al. 2017). Thus, to give a clear overview of the multivariate results, we decided to report results from multiple regression analyses while results from the multilevel models are depicted in Table 5. Our preliminary analysis indicates a non-linear effect of “family contact” on subjective well-being. We thus included these predictors as dummy variables into our models.

3 Results

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for all social capital as well as subjective well-being variables. In terms of contacts with various occupations, Austrian individuals know three out of five individuals on average from low-educated occupations (60%) and approximately two out of five from high-educated occupations (45%) as described in the method section above. While contacts with high-educated occupations do not vary between urban- and rural areas, individuals from rural areas have more contacts with low-educated occupations (F (1,832) = 10.27, p < 0.01). On average, an Austrian individual has contact with 1.3 (out of 4, equals to 32.5%) family members at least several times a week while 56% of all individuals report contact with a close friend at least several times a week. Frequent family contact however is more common in rural areas (F (1, 815) = 15.55, p < 0.01) while frequent contact with a close friend is more common in urban areas (F (1, 827) = 11.91, p < 0.01), just like social participation (F (1, 832) = 13.41, p < 0.01). One reason for this finding could be a higher supply of public meeting places such as bars, cafés, etc. in urban areas, which doesn’t necessarily result in more social contacts in urban areas since social meetings could also happen in private places. Using the alternative variables for family contact and contact with a close friend which also includes contacts “once a week”, we see an average of 1.83 family contacts (SD: 1.2, equals to 46%) and 79% contact with a close friend (SD: 0.4) with similar urban/rural results (not shown in Table 1). On average, individuals are active in about one out of three groups, but report high social support as individuals in that they can rely on other people or organizations in 9.4 out of 10 situations. There are no significant spatial differences regarding group activities and social support. Institutional trust reaches higher values than social trust. This holds for the entire sample as well as for urban and rural areas. Again, there is no significant difference between urban and rural areas.

Regarding subjective well-being, around 90% of the respondents report being at least “fairly satisfied” with their lives, 83% report feeling “rather good” or “very good” at the moment and 91% report being “fairly happy” or “very happy” (see Fig. 2). In terms of life satisfaction and momentary well-being, we only observe small and non-significant differences between urban and rural areas. Regarding happiness, 88% of individuals who live in urban areas report being “fairly happy” or “very happy” while this percentage rises to 92% in rural areas. This is in accordance with the mean happiness score, which is slightly higher in rural- compared to urban areas (see Table 1, f (818) = 7.39, p < 0.01).

Life satisfaction, momentary well-being, and happiness for the whole Austrian population as well as for urban- and rural areas. Percentages are reported for individuals who are at least “fairly satisfied” (for Life satisfaction), who feel “rather good” or “very good” (for Momentary well-being) and who report to be “fairly happy” or “very happy” (for Happiness)

Before moving to the multivariate analysis, we analyzed intercorrelations between all variables of interest (see Table 4). Life satisfaction, happiness, momentary well-being as well as subjective well-being all show similar and small correlation coefficients with social capital variables. Social capital indicators show low to moderate intercorrelations which lead to a low risk of multicollinearity during multivariate analysis. Table 2 presents the regression results for the whole sample with subjective well-being as the outcome variable. First, we include only the control variables into the model (Model 1). Further, we include structural social capital variables (Model 2), or cognitive social capital variables (Model 3). Finally, we include all variables into one model (Model 4). For the same models controlled for interviewer effects via multilevel modelling see Table 5. As pointed out in the method section above, we use dummy variables to analyze the effect of “family contact” on subjective well-being due to preliminary analysis. Overall, the control variables explain 15.1% of the variance (adjusted R2). By adding all social capital dimensions, the explained variance grows to 25.7% (adjusted R2). Cognitive social capital explains the biggest additional share of variance, namely 6.5%, whereas structural social capital explains 4.8%. The final model (Model 4) reveals that the social capital variables explain 10.6% of the additional variance combined (computed as adjusted R2 of the specific social capital block minus 15.1%).

Regarding the control variables, being unemployed has the biggest detrimental effect on subjective well-being while a high personal income as well as being married and female are positively associated with high subjective well-being in all models (except a non-significant effect of gender in model 2). Individuals between the ages of 19–27 report the highest subjective well-being, followed by individuals aged 60–74. Individuals aged (28–59 years) as well as above (74+ years) report lower subjective well-being. These results are in line with previous research (e.g. Helliwell and Putnam 2004; Portela et al. 2013). Education, church visits and urban environments show no significant effects on subjective well-being.

We now move to the results concerning social capital. Contacts with high-educated workers shows a positive impact on subjective well-being while contacts with low-educated workers, as well as social participation and group activities do not. Frequent family contact on the other hand with two or three different family members shows a small positive impact on subjective well-being whereas frequent family contact with four different family members does not. Contact with a close friend at least several times a week shows a small positive effect on subjective well-being as well. Using the alternative family contact dummy variables (which includes contact “once a week”), we see a positive effect of family contact with one member (β: 0.09) and four members (β: 0.13), while contact with two or three members shows beta coefficients of 0.21 to 0.22. The alternative dummy of contact with a close friend however does not reach significance (β: 0.06). Both the family- and friend effects remain significant after including the remaining social capital variables (the same applies for the alternative variables as well). Regarding cognitive social capital variables, social and institutional trust foster subjective well-being while social support does not. This result holds after including structural social capital variables as well.

After we examined the impact of social capital on subjective well-being for the whole population, we continued with regression models separate for urban and rural areas. Table 3 shows the key results, including the same control variables as Table 2 (except place of residence). We use the formula as proposed by Paternoster et al. (1998) to test whether the beta coefficients significantly vary between urban and rural areas. In rural areas, we see a significantly higher effect of frequent contact with one and two family members on subjective well-being compared to urban areas. Frequent contact with three family members also shows a significant effect on subjective well-being in rural areas while social trust shows a positive effect on subjective well-being in urban areas. These coefficients however do not vary significantly. Contact with a close friend as well as institutional trust on the other hand positively affects subjective well-being both in urban- and rural areas. By using the alternative dummies, we see similar differences between urban- and rural areas, but with overall higher effect sizes of family contacts and lower effect sizes of contact with a close friend, similar to the alternative results in the main analysis.

Although we can explain more variance in the rural- compared to the urban subsample (28.3% vs. 23.6%, adjusted R2), this difference is mainly due to higher variance explanation by the control variables in the rural sample (20.3% vs. 12.9%, adjusted R2, only control variables included). Taking this into account, we see that control variables explain 7.4% points more variance in rural areas whereas social capital variables explain 3.3% points more variance in urban areas.

The variable “family contacts” describes frequent contact with different family members (parents, siblings, adult child, other family member). Contact of “at least several times a week” with the respective family member translates to “yes” (or “1” in terms of dummy variables).

4 Discussion

In this study, we investigated the level of subjective well-being and social capital as well as the positive impact of social capital on subjective well-being, for the Austrian population as a whole as well as for urban and rural areas. Based on the Austrian Social Survey 2018, we were able to analyze various dimensions of social capital, namely informal and formal social networks (as part of structural social capital), social support as well as social and institutional trust (as part of cognitive social capital, see Kawachi 2008). Overall, we observed high levels of subjective well-being as well as social support amongst Austrians. Additionally, the survey allows us to distinguish between family contacts, contacts in low and high-educated occupations, contact with a close friend, and social participation as components of the informal social network. We observed more contacts with people in low-educated occupations and more family contacts in rural areas, but more frequent contact with a close friend and social participation in urban areas. These results expand upon previous literature (e.g. Sørensen 2016; Hofferth and Iceland 1998; Ziersch et al. 2009) by showing different patterns of informal social networks between urban and rural areas. Our results, however, are in line with classical sociological assumptions provided by e.g. Tönnies or Durkheim which suggest stronger social cohesion in rural societies with stronger family bonds compared to urban societies (see Durkheim 1893 [1997]; Goode 1970). While rural areas are characterized by close, family oriented social networks, urban areas offer the opportunity to individually choose one’s social networks, which could be an explanation for more frequent contact with close friends and social participation in urban areas.

By using linear regression analysis, we observed a positive impact of contacts with high-educated professionals, frequent contact with family and friends as well as social and institutional trust on subjective well-being for the entire sample. This is in accordance with previous research (e.g. Helliwell and Putnam 2004). However, while frequent family contact with up to three distinct family members fosters subjective well-being, we see no significant impact of frequent family contact with four distinct family members. Since time capacity is limited for everybody, competing interests could be the reason for this finding. “Too much” family contact limits the capacity for other well-being inducing activities, such as leisure and work (see van Praag et al. 2003). Our results with the alternative variable for family contact matches this interpretation. This alternative categorization does not only include contact “several times a week” or more often, but also contact “once a week”. Here we see that contact with four distinct family members on a (less time-consuming) weekly basis shows a beneficial effect on subjective well-being. The effect of the alternative “contact with a close friend” variable however vanishes and becomes non-significant, suggesting that contact with a close friend is only beneficial on a more or less daily basis (or, at least several times a week).

Comparing urban and rural areas, frequent contact with up to three family members fosters subjective well-being in rural-, but not in urban areas. These effects also significantly vary between urban- and rural areas for family contact with one or two family members. This result sheds new light on previous research. While Mair and Thivierge-Rikard (2010) showed a stronger effect of informal social capital on subjective well-being in rural areas for elderly people, our findings first support these results for the general population and second imply that this effect only concerns family contacts as part of informal social capital. Since family contacts are more common in rural areas, different effects could be due to different expectations (see Mair and Thievierge-Rikard 2010). Additionally, since different norms can be transmitted through social capital (see Coleman 1988), persons having few family contacts could violate these norms which could subsequently lead to implicit or explicit sanctioning of the respective individual, for example by social exclusion. We also see a positive effect of social trust on subjective well-being in urban-, but not in rural areas. This effect, however, does not differ significantly between those areas. This tendency still matches the picture of more individually driven urban areas, since trust in other people facilitates the forging of new contacts (see Delhey et al. 2018; Baumeister and Leary 1995).

Besides the positive effect of social networks and trust on subjective well-being, we observed no effect of social support on subjective well-being. Since previous studies emphasized the positive effect of social support (e.g. Siedlecki et al. 2014), this is a surprising result. We observed very high social support for the Austrian sample (9.4 on a scale from 0–10) and subsequently low variations between individuals (SD: 1.3) which could be the reason for this small, negligible relation between social support and subjective well-being. Another explanation could be due to the wording of the question as described below in the limitation section.

4.1 Limitations

Comprehensive surveys such as the Austrian Social Survey 2018 have several advantages as well as disadvantages. One advantage is that large representative samples allow inference for the total population. Since large-scale surveys usually cover several topics, only a few questions can be asked on a specific topic. Although there were numerous items on social capital in the questionnaire, we were limited to the available questions and the question-wording. In particular, the fact that we did not find evidence for an impact of social support on well-being, could be due to the formulation of the answer categories. Fernandez and Muckenhuber (2019) found clear evidence for social support affecting well-being with data from the Austrian Social Survey 2016. But while the question for the items in 2016 was “do you know someone, who would help you with …” (yes or no), the survey in 2018 asked, “Who would you turn to first to, if you need help with …”. As a proxy, we calculated the sum of all answers except “no one” but we believe that the question of knowing supportive people is the better operationalization of social support. Another limitation of the survey-based approach is the cross-sectional character of the study. Based on this data foundation, we cannot tell for sure if social capital causes subjective well-being or the other way around, and rely on theoretical assumptions for this matter. Apart from experimental designs, only longitudinal (panel-)data can approach causal results. Few studies have taken this path so far. For example, by using a cross-lagged panel design, Joshanloo et al. (2018) showed a positive effect of social well-being (a similar concept to social capital, see Keyes (1998)) on future subjective well-being but not the other way around. Moreover, by using an instrumental variable, Becchetti et al. (2009) concluded that social participation positively affects subjective well-being but not the reverse. Another limitation we have to keep in mind is the nation-specific character of a national survey. Although our results mostly confirm findings from different countries, it should be noted that relationships, such as rural-urban comparisons, can vary greatly from country to country.

4.2 Conclusion

In summary, our results confirm the beneficial effect of certain social capital dimensions on subjective well-being in Austria as well as different amounts of social capital in urban- compared to rural areas and different effects on subjective well-being. Our study shows a distinct effect of informal social networks in certain areas: While contacts in low-skilled occupations, as well as family contacts, are more common in rural areas, contacts with a close friend and social participation are more common among urban respondents. Besides differences in the amount of social capital, the effect of family contacts on subjective well-being is higher in rural- compared to urban areas. Since previous studies only reported more informal social networks in rural areas as well as a stronger effect on subjective well-being (see Sørensen 2016; Mair and Thivierge-Rikard 2010), our results expand upon previous research by showing a more differentiated picture in terms of informal social networks. These results are also in line with the theoretical assumption of stronger family bonds in rural areas (see Durkheim 1893 [1997]; Goode 1970). For the Austrian population as a whole however, contacts with high-educated professionals, frequent contact with up to three distinct family members, frequent contact with a close friend as well as social and institutional trust foster subjective well-being.

Notes

We also calculated an alternative index of social support which does not include institutional support but only personal support. We obtained the same results as with the originally described social support index.

References

Abbott, Stephen, and Della Freeth. 2008. Social capital and health: starting to make sense of the role of generalized trust and reciprocity. Journal of Health Psychology 13(7):874–883. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308095060.

Antonovsky, Aaron. 1979. Health. stress. and coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Baumeister, Roy F., and Mark R. Leary. 1995. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin 117(3):497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497.

Becchetti, Leonardo, Elena Giachin Ricca, and Alessandra Pelloni. 2009. The 60s turnaround as a test on the causal relationship between sociability and happiness. SSRN Electronic Journal https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1441901.

Berkman, F. Lisa, and Thomas Glass. 2000. Social integration, social networks, social support, and health. Social epidemiology 1:103–118.

Beullens, Koen, and Geert Loosveldt. 2016. Interviewer effects in the European social survey. Survey Research Methods 10(2):103–118.

Bjørnskov, Christian, and Kim M. Sønderskov. 2013. Is social capital a good concept? Social indicators research 114(3):1225–1242.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1986. The forms of capital. In Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education, ed. J. Karabel, J. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood.

Calvo, Rocío, Yuhui Zheng, Santosh Kumar, Analia Olgiati, and Lisa Berkman. 2012. Well-being and social capital on planet earth: cross-national evidence from 142 countries. PLoS ONE 7(8):e42793. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0042793.

Cohen, Sheldon. 2004. Social relationships and health. American psychologist 59(8):676–684.

Coleman, S. James. 1988. Social capital in the creation of human capital. American journal of sociology 94:S95–S120.

Coleman, S. James. 1990. Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Belknap Press.

Deep, Paul. 1999. Biological and biopsychosocial models of health and disease in dentistry. Journal-Canadian Dental Association 65:496–497.

Delhey, Jan, Georgi Dragolov, and Klaus Boehnke. 2018. Social cohesion and well-being in Europe. European Quality of Life Survey 2016. https://doi.org/10.2806/261816.

Diener, Ed, Richard E. Lucas, and Shigehiro Oishi. 2002. Subjective well-being: the science of happiness and life satisfaction. Handbook of positive psychology 2:63–73.

Diener, Ed, Shigehiro Oishi, and Richard E. Lucas. 2015. National accounts of subjective well-being. American Psychologist 70(3):234–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038899.

Dolan, Paul, Tessa Peasgood, and Mathew White. 2008. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology 29(1):94–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joep.2007.09.001.

Durkheim, Emile. 1997. The division of labour in society. New York: Free Press.

Fernandez, Karina, and Johanna Muckenhuber. 2019. Soziale Ressourcen, Gesundheit und Wohlbefinden in verschiedenen Altersgruppen. In Sozialstruktur und Wertewandel in Österreich, ed. Johann Bacher, Alfred Grausgruber, Max Haller, Franz Höllinger, Dimitri Prandner, and Roland Verwiebe, 285–302. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Gilbert, Keon L., C. Quinn Sandra, Robert M. Goodman, James Butler, and John Wallace. 2013. A meta-analysis of social capital and health: a case for needed research. Journal of Health Psychology 18(11):1385–1399. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105311435983.

Glatz, Christoph, and Anja Eder. 2019. Patterns of trust and subjective well-being across europe: new insights from repeated cross-sectional analyses based on the European Social Survey 2002–2016. Social Indicators Research https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02212-x.

Goode, W. James. 1970. World revolution and family patterns. New York: Free Press.

Hadler, Markus, Franz Höllinger, and Johanna Muckenhuber. 2019. Social Survey Austria 2018 (SUF edition). DOI: doi:10.11587/ERDG3O, AUSSDA Dataverse, V3. https://data.aussda.at/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.11587/ERDG3O. Accessed 30-01-2020.

Helliwell, J.F., and R.D. Putnam. 2004. The social context of well-being. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 359(1449):1435–1446. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2004.1522.

Hofferth, L. Sandra, and John Iceland. 1998. Social capital in rural and urban communities. Rural Society 63(4):574–598.

Hox, Joop, Mirjam Moerbeek, and Rens Van de Schoot. 2017. Multilevel analysis: techniques and applications. Schoot: Routledge.

Joshanloo, Mohsen, M. Joseph Sirgy, and Joonha Park. 2018. Directionality of the relationship between social well-being and subjective well-being: evidence from a 20-year longitudinal study. Quality of Life Research 27(8):2137–2145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1865-9.

Kawachi, Ichirō (ed.). 2008. Social capital and health. New York: Springer.

Keyes, Corey Lee M. 1998. Social well-being. Social Psychology Quaterly 61(2):121–140. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787065.

Kmet, M. Bernadette, and Bernhard Weicht. 2019. Relevanz von zentralen Lebensbereichen: Konstanz oder Wandel. In Sozialstruktur und Wertewandel in Österreich, ed. Johann Bacher, Alfred Grausgruber, Max Haller, Franz Höllinger, Dimitri Prandner, and Roland Verwiebe, 25–50. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Kroll, Christian. 2008. Social Capital and the Happiness of Nations: The Importance of Trust and Networks for Life Satisfaction in a Cross-National Perspective. Frankfurt am Main, New York: Peter Lang.

Liu, Huijun, Li Shuzhuo, Xiao Qunying, and M.W. Feldman. 2014. Social support and psychological well-being under social change in urban and rural China. Social indicators Research 119:979–996.

Mair, A. Christine, and R.V. Thivierge-Rikard. 2010. The strength of strong ties for older rural adults: regional distinctions in the relationship between social interaction and subjective well-being. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 70(2):119–143. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.70.2.b.

McLeod, Saul. 2007. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Simply psychology 1:1–18.

Mikucka, Malgorzata, Francesco Sarracino, and Joshua K. Dubrow. 2017. When does economic growth improve life satisfaction? Multilevel analysis of the roles of social trust and income inequality in 46 countries, 1981–2012. World Development 93:447–459. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.01.002.

Oishi, Shigehiro, and Ulrich Schimmack. 2010. Culture and well-being: a new inquiry into the psychological wealth of nations. Perspectives on Psychological Science 5(4):463–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610375561.

Okun, Morris A., William A. Stock, Marilyn J. Haring, and Robert A. Witter. 1984. Health and subjective well-being: a meta-analyis. The International Journal of Aging and Human Development 19(2):111–132. https://doi.org/10.2190/QGJN-0N81-5957-HAQD.

van Oorschot, Wim, and Wil Arts. 2005. The social capital of European welfare states: the crowding out hypothesis revisited. Journal of European Social Policy 15(1):5–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928705049159.

Paternoster, Raymond, Robert Brame, Paul Mazerolle, and Alex Piquero. 1998. Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology 36(4):859–866.

Portela, Marta, Isabel Neira, and Maria del Mar Salinas-Jiménez. 2013. Social capital and subjective wellbeing in europe: a new approach on social capital. Social Indicators Research 114(2):493–511.

Portes, Alejandro. 1998. Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual review of sociology 24(1):1–24.

Pressman, Sarah D., and Sheldon Cohen. 2005. Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin 131(6):925–971. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925.

Puntscher, Sibylle, Christoph Hauser, Janette Walde, and Gottfried Tappeiner. 2015. The impact of social capital on subjective well-being: a regional perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies 16(5):1231–1246. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9555-y.

Putnam, Robert D. 1993. Making democracy work. Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Putnam, Robert D. 2001. Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Siedlecki, Karen L., Timothy A. Salthouse, Shigehiro Oishi, and Sheena Jeswani. 2014. The relationship between social support and subjective well-being across age. Social Indicators Research 117(2):561–576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0361-4.

Sørensen, Jens F.L. 2012. Testing the hypothesis of higher social capital in rural areas. The case of Denmark. Regional Studies 46:873–891.

Sørensen, Jens F.L. 2016. Rural—urban differences in bonding and bridging social capital. Regional Studies 50(3):391–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2014.918945.

Tobiasz-Adamczyk, Beata, and Katarzyna Zawisza. 2017. Urban-rural differences in social capital in relation to self-rated health and subjective well-being in older residents of six regions in Poland. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine 24(2):162–170. https://doi.org/10.26444/aaem/74719.

Van Praag, B.M.S., P. Frijters, and A. Ferrer-i-Carbonell. 2003. The anatomy of subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 51(1):29–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167-2681(02)00140-3.

Ziersch, Anna, Fran Baum, I. Gusti Darmawan, Anne M. Kavanagh, and Rebecca J. Bentley. 2009. Social capital and health in rural and urban communities in South Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 33:7–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-6405.2009.00332.x.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Graz.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Glatz, C., Bodi-Fernandez, O. Individual social capital and subjective well-being in urban- and rural Austrian areas. Österreich Z Soziol 45, 139–163 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-020-00399-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-020-00399-9