Abstract

Background

We previously validated a 5-item compassion measure to assess patient experience of clinician compassion in the outpatient setting. However, currently, there is no validated and feasible method for health care systems to measure patient experience of clinician compassion in the inpatient setting across multiple hospitals.

Objective

To test if the 5-item compassion measure can validly and distinctly measure patient assessment of physician and nurse compassion in the inpatient setting.

Design

Cross-sectional study between July 1 and July 31, 2020, in a US health care network of 91 community hospitals across 16 states consisting of approximately 15,000 beds.

Patients

Adult patients who had an inpatient hospital stay and completed the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey.

Measurements

We adapted the original 5-item compassion measure to be specific for physicians, as well as for nurses. We disseminated both measures with the HCAHPS survey and used confirmatory factor analysis for validity testing. We tested reliability using Cronbach’s alpha, as well as convergent validity with patient assessment of physician and nursing communication and overall hospital rating questions from HCAHPS.

Results

We analyzed 4756 patient responses. Confirmatory factor analysis found good fit for two distinct constructs (i.e., physician and nurse compassion). Both measures demonstrated good internal consistency (alpha > 0.90) and good convergent validity but reflected a construct (compassionate care) distinct from what is currently captured in HCAHPS.

Conclusion

We validated two 5-item tools that can distinctly measure patient experience of physician and nurse compassion for use in the inpatient hospital setting in conjunction with HCAHPS.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The construct of compassion is commonly defined as the emotional response to another’s pain or suffering involving an authentic desire to help.1,2,3 Compassion is differentiated from empathy in that empathy is defined as an affective state of sensing and understanding another’s emotions. In other words, in healthcare, empathy is a feeling the clinician has, as opposed to compassion, which encompasses positive behaviors which patients can perceive.3 Clinician compassion during patient care is considered by both patients and physicians to be a vital element of high-quality care,4 and previous research has shown compassion to be associated with better clinical outcomes across numerous conditions.5,6,7,8,9,10 In addition, focus on compassionate care may have financial impact on healthcare organizations given that a lack of compassion has been associated with increased resource utilization, healthcare spending, and malpractice expense.11,12,13,14,15,16,17

Given that patient perception of compassionate care (as opposed to self-assessment of compassion by the clinician or third party observer assessment of compassion) is associated with patient outcomes and healthcare costs, we previously developed and validated a 5-item compassion measure to assess patient experience of clinician compassion in the outpatient setting,18 which can be administered with the Clinician and Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS) survey. The CG-CAHPS is a patient satisfaction survey for adult outpatient clinic visits used by the United States (US) Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services for all healthcare organizations that receive payments from Medicare.19 While we initially validated the 5-item compassion measure in the outpatient setting, assessing patients’ perception of compassion from a single provider, we subsequently tested the validity of the 5-item compassion measure to assess patients’ overall perception of compassion (i.e., perceived aggregate compassion from multiple clinicians) across three US emergency departments (ED) and found it to be reliable and valid in this setting as well.20 It is further possible that the 5-item compassion measure could be utilized to assess overall clinician compassion during hospitalization by administering it with the CAHPS Hospital Survey (HCAHPS), similar to HCAHPS methods in assessing overall patient experience. The 5-item compassion measure has also not been previously validated to differentiate between different types of clinicians (e.g., physicians and nurses) as the HCAHPS survey has. There is currently evidence that compassion in healthcare is suboptimal worldwide.5 This is a significant public health issue given the impact that compassion (or lack thereof) can have on outcomes for patients and healthcare organizations. Thus, having the means to measure patient assessment of compassionate care in hospitals on a large scale is important for healthcare quality.

The objectives of this study were to (1) psychometrically validate the 5-item compassion measure when administered with the HCAHPS survey for inpatient hospital care, and (2) to test if the 5-item compassion measure is a valid and reliable tool to quantify two distinct constructs (i.e., physician compassion and nurse compassion) for hospitalized patients.

METHODS

Setting

This study was conducted across a US acute hospital system, which consists of 91 hospitals within 16 states (Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Mississippi, Missouri, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Texas, West Virginia). The included institutions are community hospitals without any associations to universities and compose approximately 15,000 beds in total. The study took place from July 1 to July 31, 2020. Given this research involved only survey procedures and information was recorded in such a manner that subjects could not be identified, the Institution Review Board at our institution (Cooper University Health Care, Camden, NJ) considered this study exempt from the 45 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) requirements as per regulation 45 CFR 46.101(b).2, 18, 21 This study is reported in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement.22

Study Population

The study population included patients’ age ≥ 18 who had at least one overnight stay in the hospital as an inpatient and completed the HCAHPS survey. We matched our inclusion criteria to correspond with the HCAHPS survey given that a primary objective of this measurement tool is to work in conjunction with the HCAHPS platform for dissemination at scale (see Supplemental Methods).

5-Item Compassion Measure

For the purposes of this study, and for dissemination with the HCAHPS survey, each of the five items of the original measurement tool were modified to specifically elicit separate responses for interactions with physicians and nurses (i.e., 10 items total) and are displayed in Table 1 (see Supplemental Methods).

Statistical Analysis

Patient survey responses were described using median and interquartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and frequency and proportions for categorical variables.

Separate confirmatory factor analyses (using structural equation modeling) were used to test how well the 5-item compassion measure assessed a single construct of compassion from physicians and a separate single construct for compassion from nurses, as well as to calculate standardized coefficients for each item. Structural equation modeling tests if the hypothesized model (i.e., two discrete constructs, compassion from physicians, and compassion from nurses) matches the observed data. The Supplemental Methods further describe these models. Reliability was tested separately for the physician and nurse 5-item compassion measures, using Cronbach’s alpha. Cronbach’s alpha is a measure of internal reliability, or how closely the set of items in a measurement tool are related as a group.

We summed the scores for each individual item to obtain two separate composite scores, one for the physician 5-item compassion measure and one for the nurse 5-item compassion measure. Using Spearman correlation coefficients, we tested divergent validity between the two 5-item compassion measure total scores. We hypothesized that while the two 5-item compassion measures would have a positive correlation, they would be distinct from one another. To further test if the items from the two 5-item compassion measures form discrete constructs (i.e., measure physician and nursing compassion separately as opposed to a single construct of overall compassion), we used structural equation modeling to test model fit for a single construct model (combining physician and nurse tools as a single measure) versus a two-construct model with physician and nurse compassion measured separately.18 The Supplemental Methods further describes these analyses.

Pairwise Spearman correlation coefficients were used to test convergent validity between the physician 5-item compassion measure total scores and the HCAHPS physician communication questions (ability to listen, explain, and show courtesy and respect) and overall hospital rating (i.e., HCAHPS question, using any number from 0 to 10, where 0 is the worst hospital possible and 10 is the best hospital possible, what number would you use to rate this hospital?). We repeated this procedure for the nurse 5-item compassion measure. We hypothesized that while the two 5-item compassion measures would have a positive correlation with the HCAHPS constructs (i.e., patients who report higher compassion would also report better communication and overall hospital rating), these correlations would not be perfect (i.e., would be distinct and not redundant measures).

We further evaluated convergent and divergent validity between the 5-item compassion measures and the above HCAHPS constructs using structural equation modeling to perform mediation (i.e., causal pathway) testing. In building our model, we first designated four latent variables: (1) physician compassion; (2) nursing compassion; (3) physician communication (HCAHPS physician communication questions); and (4) nursing communication (HCAHPS nursing communication questions). We tested the associations between these four latent variables and overall hospital rating obtained from the HCAHPS. We further tested to what degree physician communication mediated the association between physician compassion and overall hospital rating (i.e., hypothesized model: increased physician compassion leads to better communication, which in turn leads to improved overall hospital rating). We also tested if physician communication mediated the association between nursing compassion and overall hospital rating. We expected (1) all four latent variables to be independently associated with overall hospital rating (convergent validity), (2) physician communication to partially mediate the association between physician compassion and overall hospital rating (i.e., while physician compassion and communication are expected to overlap, full mediation would suggest physician communication and physician compassion are not distinct constructs), and (3) if patients are able to distinguish between physician and nurse constructs, then physician communication should be independent of nurse compassion and will not mediate the association between nursing compassion and overall hospital rating (divergent validity). We repeated the mediation testing using nurse communication as the mediator. To estimate the mediation models, we used full information maximum likelihood and used robust standard errors clustered at the hospital level.

RESULTS

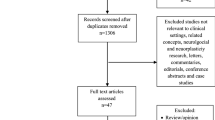

Response rates are displayed in Figure 1. Of the 91 hospitals included, the median (IQR) number of responses included in the analyses per hospital was 41 (21-73). Patient self-reported characteristics are displayed in Table 2. The age range was 18 to 100 years old, 60% of participants were female, 57% had some degree of college education, and the majority were non-Hispanic white.

Confirmatory factor analysis found all five items loaded well on separate single constructs for both the physician and the nurse measures (Table 3). We found both models had a good fit to the observed data (Supplemental Results). Internal reliability was excellent for both the physician and nursing 5-item compassion measures, Cronbach’s alpha = 0.96 and 0.95 respectively.

The 5-item compassion measure for both physicians and nurses ranged the full scale (5 to 20) Consistent with trends in patient satisfaction data in the USA, the responses trended favorably (i.e., negatively skewed).18, 23 The distributions for both the physician and nurse 5-item compassion measure scores are displayed in Figure 2.

The physician 5-item compassion measure had only a moderate correlation with the nurse 5-item compassion measure (i.e., while they trend in the same direction, they are discrete and not redundant) r = 0.68, p < 0.001. Using confirmatory factor analysis, we found a two-factor model (physician and nurse 5-item compassion measures loading on separate latent variables) to have a better fit to the observed data, compared to the single factor model (both the physician and nurse 5-item compassion measures loading on a single latent variable) (Supplemental Results). These results provide further evidence that the physician and nurse compassion measures are measuring discrete constructs.

We found the physician 5-item compassion measure to only have a moderate association with the HCAHPS physician communication and overall hospital rating, r = 0.69 (p < 0.001) and r = 0.55 (p < 0.001) respectively. Similar results were found for the nurse 5-item compassion measure and the HCAHPS nursing communication and overall hospital rating, r = 0.69 (p < 0.001) and r = 0.62 (p < 0.001) respectively. As we hypothesized, these results suggest the compassion measures trend in the same direction as the HCAHPS communication questions but do not simply reflect a redundant measure of patient experience already captured by the HCAHPS questions.

Our mediation model found all four latent variables to be independently associated with overall hospital rating (direct associations displayed in Table 4). As expected, physician compassion was associated with physician communication (β = 0.52 (95% CI 0.48 to 0.55)), and physician communication partially mediated the association between physician compassion and overall hospital rating (indirect effect, β = 0.27 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.42)). Thus, physician communication mediated only 44% of the total association between physician compassion and overall hospital rating. In other words, this model suggests physician compassion is a distinct construct that may improve physician communication, and further physician compassion may directly improve overall hospital rating, as well as have an indirect effect on overall hospital rating through its effects on physician communication.

Furthermore, as expected, we did not find nurse compassion to be associated with physician communication (β = 0.02 (95% CI -0.01 to 0.05)), and physician communication did not mediate the association between nurse compassion and overall hospital rating (β = 0.01 (95% CI -0.003 to 0.03)). These results further suggest nurse compassion is a distinct construct that does not influence physician communication. Similar results were found using nurse communication (Supplemental Results).

DISCUSSION

This study provides the initial validation of two measurement tools for patient assessment of physician and nurse compassion in hospitals. We found the two 5-item compassion measures were able to reliably assess physician and nurse compassion separately. Mediation testing found that while there were important associations between compassion, communication, and overall hospital rating, the physician and nurse 5-item compassion measures allow for specific assessments of compassion, which are distinct from, and add additional information to, the HCAHPS questions. For example, if we had found compassion was not associated with communication or overall hospital rating at all, it would have brought convergent validity into question. Alternatively, if communication mediated 100% of the association between compassion and overall hospital rating, it would have suggested that there was no difference between the constructs measured by the 5-item compassion measures and the constructs measured by the HCAHPS communication questions (i.e., redundant measures). Also, if physician compassion was found to be associated with nurse communication, or if nurse communication mediated the association between physician compassion and overall hospital rating, it would have suggested the measures were unable to distinguish separate physician and nurse constructs (i.e., our results support appropriate divergent validity). Thus, these models provide evidence that the physician and nurse 5-item compassion measures are able to measure distinct constructs.

The physician and nurse 5-item compassion measures are novel in that (1) they are patient assessments of compassion, as opposed to a third party observer or self-assessment (which is important because it is likely the patients’ experience that drives the association between compassion and clinical outcomes)10, 18; (2) they are brief, allowing dissemination with HCAHPS for large-scale assessment of compassion across healthcare organizations; and (3) they allow for distinct assessments of nurse and physician compassion, as opposed to an overall measure of clinician compassion.

The validation of the 5-item compassion measure in the inpatient setting has implications for future research. Being compassionate is not simply an inherent trait, which clinicians either do or do not possess, but evidence supports that compassionate behaviors can in fact be taught and learned.2, 24 The use of an easily distributed, validated measurement tool for patient assessment of compassion will allow for rigorous testing of interventions aimed at increasing clinician compassion and improving subsequent long-term outcomes (both clinical and economic).18 For example, by being able to measure compassion on a large scale across healthcare organizations, it may be possible to rapidly identify where within healthcare institutions compassionate care may be lacking, allowing for testing of focused interventions to increase compassion. In addition, the results of our mediation testing support patient assessment of compassion as a potential target to improve clinician-patient communication, as well as overall patient satisfaction. While our hypothesized causal pathway suggests increasing compassion may improve communication, it is similarly reasonable to hypothesize that improving communication may lead to greater perceived compassion. Future research is warranted to further evaluate these associations. We also believe future research is required to examine the impact of patient-clinician concordance/discordance in gender, race, and age on patient perception of compassionate care, as well as to validate the 5-item compassion measure in other languages.

We acknowledge that this study has important limitations to consider. First, the response rate in this study was consistent with low response rates seen in previous studies involving HCAHPS surveys.18, 25, 26 However, healthcare organizations can only estimate their patient experience metrics using data from responders, and the results of the psychometric analyses among those who did respond across these 91 hospitals suggest the physician and nurse 5-item compassion measures are valid and reliable assessments of patients’ perception of compassion. However, research is warranted to determine if non-response bias affects overall patient experience metrics. Similarly, we only tested the validity and reliability of the 5-item compassion measure on individuals who were sent the HCAHPS survey. Thus, these results cannot be generalized to those excluded from the HCAHPS survey. It is also important to note that the majority of the respondents were non-Hispanic white. Second, while the results of this study support that physician and nursing compassion can be measured distinctly, the study only supports the use of the 5-item compassion measure to obtain an overall physician and an overall nursing compassion score over the course of the entire hospitalization. While the 5-item compassion measure was previously demonstrated to be reliable and valid in assessing the compassion of a single physician in the outpatient setting,18 further research is required to test if the 5-item compassion measure can be used to assess individual physicians and nurses in the inpatient setting where patients typically are cared for by multiple clinicians. Specifically, research is required to determine how the compassion scores are affected when patients do not experience the same degree of compassion from all doctors and all nurses. Third, while we found patient assessment of compassion to be associated with clinician communication, further research is needed to determine what other clinician behaviors, as well as what non-clinician variables (e.g., severity of illness, hospital factors, timing of measurements) are associated with patient assessment of compassion. Interestingly, while we found a similar association between physician compassion and communication as we did for nurse compassion and communication, nurse communication had a stronger association with overall hospital rating and mediated more of the association between nurse compassion and overall hospital rating. This is likely secondary to nurse compassion and communication having a stronger total association with overall hospital rating compared to the physician constructs, possibly due to the fact that in general, nurses spend more time with the patient throughout the hospitalization. Fourth, this study did not assess advanced nurse practitioners or physician assistants. Fifth, this study was performed during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and the number of patients hospitalized for COVID-19 during our study period is unknown. However, we have no reason to suspect the pandemic would affect the validity or reliability of the 5-item compassion measure given our previous work performed outside of the pandemic.18, 20

In summary, the physician and nurse 5-item compassion measures appear to be reliable and valid tools to distinctly measure patient assessment of physician and nurse compassion in the inpatient setting across multiple hospitals. Further testing among varying cohorts is warranted to further test the generalizability of these measurement tools.

References

Goetz JL, Keltner D, Simon-Thomas E. Compassion: an evolutionary analysis and empirical review. Psychol Bull. 2010;136(3):351-74.

Sinclair S, Norris JM, McConnell SJ, Chochinov HM, Hack TF, Hagen NA, et al. Compassion: a scoping review of the healthcare literature. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:6.

Singer T, Klimecki OM. Empathy and compassion. Curr Biol. 2014;24(18):R875-R8.

Lown BA, Rosen J, Marttila J. An agenda for improving compassionate care: a survey shows about half of patients say such care is missing. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30(9):1772-8.

Trzeciak S, Roberts BW, Mazzarelli AJ. Compassionomics: Hypothesis and experimental approach. Med Hypotheses. 2017;107:92-7.

Burns DD, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Therapeutic empathy and recovery from depression in cognitive-behavioral therapy: a structural equation model. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60(3):441-9.

Neumann M, Wirtz M, Bollschweiler E, Mercer SW, Warm M, Wolf J, et al. Determinants and patient-reported long-term outcomes of physician empathy in oncology: a structural equation modelling approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69(1-3):63-75.

Zachariae R, Pedersen CG, Jensen AB, Ehrnrooth E, Rossen PB, von der Maase H. Association of perceived physician communication style with patient satisfaction, distress, cancer-related self-efficacy, and perceived control over the disease. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(5):658-65.

Steinhausen S, Ommen O, Antoine SL, Koehler T, Pfaff H, Neugebauer E. Short- and long-term subjective medical treatment outcome of trauma surgery patients: the importance of physician empathy. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:1239-53.

Moss J, Roberts MB, Shea L, Jones CW, Kilgannon H, Edmondson DE, et al. Healthcare provider compassion is associated with lower PTSD symptoms among patients with life-threatening medical emergencies: a prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2019;45(6):815-22.

Bertakis KD, Azari R. Patient-centered care is associated with decreased health care utilization. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(3):229-39.

Epstein RM, Franks P, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Miller KN, Campbell TL, et al. Patient-centered communication and diagnostic testing. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(5):415-21.

Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, Warner G, Moore M, Gould C, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ. 2001;323(7318):908-11.

Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, McWhinney IR, Oates J, Weston WW, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796-804.

Moore PJ, Adler NE, Robertson PA. Medical malpractice: the effect of doctor-patient relations on medical patient perceptions and malpractice intentions. West J Med. 2000;173(4):244-50.

Vincent C, Young M, Phillips A. Why do people sue doctors? A study of patients and relatives taking legal action. Lancet. 1994;343(8913):1609-13.

Betts D, Balan-Cohen A, Shukla M, Kumar N. The Value of Patient Experience: Hospitals with Better Patient-Reported Experience Perform Better Financially. Washington, DC: Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. 2016.

Roberts BW, Roberts MB, Yao J, Bosire J, Mazzarelli A, Trzeciak S. Development and Validation of a Tool to Measure Patient Assessment of Clinical Compassion. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(5):e193976.

Dyer N, Sorra JS, Smith SA, Cleary PD, Hays RD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS(R)) Clinician and Group Adult Visit Survey. Med Care. 2012;50 Suppl:S28-34.

Sabapathi P, Roberts MB, Fuller BM, Puskarich MA, Jones CW, Kilgannon JH, et al. Validation of a 5-item tool to measure patient assessment of clinician compassion in the emergency department. BMC Emerg Med. 2019;19(1):63.

Protection of Human Subjects, 45 C.F.R. § 46.101. 2009. available at: https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/regulatory-text/index.html.

von Elm E, Altman, DG, Egger, M, Pocock, SJ, Gotzsche, PC, Vandenbroucke, JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;147(8):573-7.

Nelson EC, Gentry MA, Mook KH, Spritzer KL, Higgins JH, Hays RD. How many patients are needed to provide reliable evaluations of individual clinicians? Med Care. 2004;42(3):259-66.

Kelm Z, Womer J, Walter JK, Feudtner C. Interventions to cultivate physician empathy: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2014;14:219.

Etier BE, Jr., Orr SP, Antonetti J, Thomas SB, Theiss SM. Factors impacting Press Ganey patient satisfaction scores in orthopedic surgery spine clinic. Spine J. 2016;16(11):1285-9.

Garcia LC, Chung S, Liao L, Altamirano J, Fassiotto M, Maldonado B, et al. Comparison of Outpatient Satisfaction Survey Scores for Asian Physicians and Non-Hispanic White Physicians. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(2):e190027.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

None of the authors have relationships with commercial interests. Drs. Trzeciak and Mazzarelli are co-authors of a book on compassion science entitled “Compassionomics” and donate all author proceeds to the Cooper Foundation. They sometimes receive payments for speaking engagements related to the book. Dr. Roberts has received payments for speaking engagements related to clinician compassion.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

ESM 1

(DOCX 33 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Roberts, B.W., Roberts, M.B., Mazzarelli, A. et al. Validation of a 5-Item Tool to Measure Patient Assessment of Clinician Compassion in Hospitals. J GEN INTERN MED 37, 1697–1703 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06733-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-06733-5