Abstract

Background

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV is effective, yet many providers continue to lack knowledge and comfort in providing this intervention. It remains unclear whether internal medicine (IM) residents receive appropriate training in PrEP care and if this affects their future practices.

Objective

We sought to evaluate the relationship between current IM residents’ prior PrEP training and knowledge, comfort, and practice regarding the provision of PrEP.

Design and Participants

We created an online survey to assess IM residents’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors related to PrEP. The survey was distributed among five IM programs across the USA.

Key Results

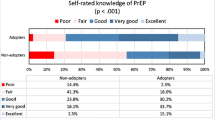

We had a 35% response rate. Of 229 respondents, 96% (n = 220) had heard of PrEP but only 25% (n = 51) had received prior training and 11% (n = 24) had prescribed PrEP. Compared with those without, those with prior training reported good to excellent knowledge scores regarding PrEP (80% versus 33%, p < 0.001), more frequent prescribing (28% versus 7%, p = 0.001), and higher comfort levels with evaluating risk for HIV, educating patients, and monitoring aspects of PrEP (75% versus 26%, 56% versus 16%, and 47% versus 8%, respectively; all p values < 0.0001). While only 25% (n = 51) had received prior training, 75% (n = 103) of respondents reported that training all providers at their continuity clinic sites would improve implementation.

Conclusions

We found that prior training was associated with higher levels of self-reported PrEP knowledge, comfort, and prescribing behaviors. Given the significant need for PrEP, IM residents should be trained to achieve adequate knowledge and comfort levels to prescribe it. This study demonstrates that providing appropriate PrEP training for IM residents may lead to an increase in the pool of graduating IM residents prescribing PrEP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the proven effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) against the acquisition of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) among high-risk individuals,1, 2 provider adoption remains low. Emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (FTC/TDF, trade name Truvada®, Gilead Sciences Inc.), the only FDA-approved form of HIV PrEP, has been shown in multiple studies to reduce the risk of HIV infection in adults with high-risk sexual activity and persons with injection drug use.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) guidelines have been in place since 2014,4 but prior studies have shown significant barriers to prescribing PrEP, from lack of provider knowledge and comfort to concerns for cost, side effects, and increased risk in sexual behavior.5,6,7,8

Studies suggest that addressing knowledge and skills gaps in these areas is a key to increasing provision of PrEP. A qualitative survey of providers revealed significant knowledge gaps in identifying target populations, prescribing, and monitoring of PrEP and a lack of consensus among protocols.9 Canadian clinicians face similar barriers, with over 75% reporting that information has not been adequately disseminated to physicians and only 12% reporting having prescribed PrEP.10 Increased knowledge of PrEP is associated with higher rates of past prescriptions and future intent to prescribe, regardless of provider type.7 Among general internists, both self-reported knowledge and experience with HIV care have been shown to correlate with higher rates of PrEP prescribing.11 At-risk populations also face knowledge barriers and importantly, having a primary care physician who was aware of their risk status has been shown to be associated with increased patient awareness of PrEP.12,13,14

While barriers exist across the care spectrum, medical educators are well-suited to address training and behavior concerns during residency in order to help close this gap in care. While didactics like continuing medical education (CME) can improve knowledge scores, they often fail to translate into practice change.15 On the other hand, factors that have been shown to improve implementation of guidelines into practice (e.g., individual face-to-face teaching, a supportive environment, and influence of well-respected physician champions) are common components of residency training.16 Training during residency affords the opportunity for additional reinforcement including delineation of expected practice patterns, directed audit, and feedback and active intervention within the clinical setting.17 Clinician educators are role models in encouraging resident adoption of guidelines including HIV testing18 and resident practice has been shown to reflect preceptor prescribing practices.19, 20

A 2015 survey11 of members of the Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) found that of the resident respondents, 22% reported PrEP adoption, significantly fewer than the 38% of attending physicians surveyed. However, this survey had fewer than 50 resident respondents, and no other studies have assessed resident populations. To establish baseline characteristics of this population and understand the role of training for PrEP, we sought to understand the current self-reported knowledge, attitudes, behaviors, and experiences of IM residents in using PrEP. Based on prior research, we hypothesize that adequate PrEP training during IM residency would increase the number of current and future PrEP prescribers.

METHODS

From April through June of 2016, we conducted a survey of self-reported PrEP knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and experience among IM residents at five academic medical centers: Johns Hopkins Hospital, Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Yale School of Medicine, University of Washington, and Ohio State University. The survey was adapted from a prior PrEP survey of Society of General Internal Medicine (SGIM) members,11 which assessed self-reported knowledge of and prior training regarding PrEP, its efficacy and side effects, and practice characteristics and adoption of PrEP prescribing. Additional questions were added to investigate issues specific to training and resident experience (i.e., how faculty supervision may have affected prescribing behavior, preferred implementation strategy in resident clinics, and barriers to prescribing PrEP). After confirming residency status, the survey provided a brief description of PrEP and a formal definition but also noting the common terminology of Truvada as equivalent to PrEP. Questions regarding self-reported basic knowledge of PrEP and its side effects followed, including specific questions regarding training during residency. Finally, we assessed resident comfort levels in prescribing PrEP. We finished by asking about their prior prescribing habits (see Appendix 1 for full survey). The 50-question survey was administered in English and included questions regarding demographics and practice characteristics. We piloted our adaptation of the survey with four resident colleagues in training across the USA with experience in HIV PrEP and survey design to confirm acceptability of survey length, content, and readability of questions.

All residents in five residency programs received recruitment emails for the online survey on Qualtrics via program listservs sent by study coordinators at each site. Two follow-up emails were sent over the 2-month period as reminders to complete the survey. The recruitment email included a brief introduction to the survey, along with a disclosure and the notation of a raffle drawing for a $20 Amazon gift card. Institutional review board exempt status from Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine was granted for this project prior to the release of the survey to the subjects. Surveys were excluded in the case of preliminary training status (neurology interns, n = 2). Not all respondents completed all survey items and we have shown the number of responses per item.

In terms of statistical analysis, we ran a chi-square analysis for our categorical data using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) 9.4 to see if there were any significant associations between survey items and whether residents had received prior training on PrEP. Fisher’s exact tests were performed instead of chi-square analyses when cell counts were too low for chi-square tests to be reliable. Due to small sample size in certain categories, we were unable to perform multivariate analyses.

RESULTS

We obtained a response rate of 35% based on residency program sizes and the number of submitted surveys (n = 229) (Table 1). The response rates from the five sites ranged from 13 to 47%. Our respondents did not differ significantly by age, race, or ethnicity from nationwide demographics for internal medicine residents, but did have a higher proportion of women (52% versus 43%, p = 0.02).21 The average age of respondents was 30 years old (age range 23–41) and the sample was relatively even among self-identified men and women and among training years, with a slightly higher representation of PGY-1 level residents. A majority of respondents self-identified as White or Asian. The vast majority (95%) reported a heterosexual orientation. Beyond a slight trend among non-heterosexual respondents, there were no statistically significant demographic differences among those that received training and those that had not.

Of those surveyed, 96% had heard of PrEP. Three-quarters of the sample received no prior training on PrEP with no significant differences among the programs surveyed. Respondents who had received prior training reported lecture, discussion, or practice-based protocol review as the source of their prior knowledge of PrEP. Nevertheless, nearly 90% of all respondents regardless of prior training believed they needed more education prior to feeling comfortable prescribing PrEP. More than half rated their knowledge of the medication (55%) and its side effects (76%) as only poor or fair. While only 11% had prescribed PrEP during their residency, 85% said that they would. A majority of respondents (84%) believed their attending would be supportive of PrEP prescribing by a resident.

Those who had received prior training in PrEP differed significantly in self-reported knowledge, attitudes, and practice from those who had not received training (Table 2). Residents who had received training were much more likely to report better knowledge of PrEP and its side effects and were also more likely to endorse its efficacy. Residents who rated their knowledge more highly reported a greater likelihood of prescribing PrEP in the future (Fig. 1).

To further understand the impact of training on willingness to prescribe PrEP, we evaluated resident comfort level with identifying target populations based on CDC recommendations, providing patient education and monitoring therapy (Fig. 2). Residents with prior training were much more comfortable evaluating eligibility for PrEP, educating patients on its use, and monitoring for side effects, toxicity, and requirements for screening for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Lastly, we assessed the impact of training on resident willingness to prescribe PrEP among different risk groups (Fig. 3 in the Appendix 2). Training was associated with increased willingness to prescribe PrEP for MSM and for HIV negative females coupled with HIV-positive male partners. No differences were seen in willingness to prescribe for other serodiscordant couples, where willingness was high in both groups. All residents, those who had received training as well as those who had not, reported comparative reluctance to prescribe PrEP to persons with active injection drug use.

Residents noted several barriers to prescribing PrEP during their training (Table 3). The most common barriers were ranked on a Likert scale. Lack of education, lack of clinic protocols, and lack of preceptor support were larger barriers for those who had not done prior training. In light of these barriers, when asked about the most feasible approach to PrEP implementation at their residency clinics, 70% of the all respondents believed that all providers should receive training about PrEP, while only 22% and 6% believed it best to have an onsite PrEP specialist or referral to an outside provider, respectively.

DISCUSSION

This study provides new information regarding lack of training among IM residents for PrEP. Our findings expand upon a prior survey of SGIM members,11 confirming low numbers of “adopters” among residents while identifying specific areas for improvement, with recommendations from the residents themselves. Although the majority of IM residents had heard of PrEP, few had received PrEP training and even fewer had prescribed PrEP. The majority reported a perceived need for more education before feeling comfortable prescribing PrEP. In contrast to post-graduate physicians,22 most felt that all providers should receive specific training for PrEP, while a minority felt that a PrEP specialist or referral base would be more prudent. Our findings are the first to our knowledge looking specifically at IM residents.

Guidelines can influence physician behavior and promote adoption of new practices such as PrEP23; however, effectively enacting guidelines requires translation into practice. Studies have shown that while dissemination of guidelines is important, their implementation is best achieved by multifaceted approaches that incorporate active learning and feedback.24 Residency training combines aspects of didactic training as well as role modeling, audit, and feedback. Additionally, studies show that young physicians may be more open to adoption and change.25 Thus, as suggested by this study, starting at the graduate medical education (GME) level may prove very important in educating a healthcare workforce comfortable and trained in prescribing PrEP.

Our survey found that training is associated with a significant improvement in resident self-reported knowledge, attitudes, and intent to prescribe. Currently, the majority of resident PrEP education is delivered through lecture, discussion, or review of a protocol. In addition, a high percentage of residents reported clinical mentors that were supportive—thus, residency has a unique infrastructure to teach and translate guidelines into practice. However, less than a third of residents, even among PGY-3s, reported prior training. This suggests that training is not being delivered uniformly. While this study did not discern the most effective way to train residents, be it through workshops, seminars, or OSCEs (objective structured clinical examinations),23, 26 determining efficacy and then developing a format which can be widely disseminated within and across programs will be key.

Self-reported knowledge of PrEP was highest among those who reported training. As in other studies, those with higher knowledge were more likely to report intention to prescribe PrEP.23 Reported confidence in educating patients was also higher among residents who received prior training. Patient education regarding PrEP has been identified in other studies as another means of increasing uptake of HIV prevention.12,13,14 Self-reported knowledge of side effects and comfort with monitoring parameters was the lowest scoring areas for all residents. Providing further training and tools like standard protocols may be beneficial to address these learning needs.27

Because provision of PrEP relies on initial risk assessment, comfort with discussion of high-risk behaviors is essential.26 Those who received prior HIV PrEP training reported greater comfort with evaluating patients for PrEP. In practice, residents with prior training reported initiating a conversation about PrEP more than those without. However, similar to post-graduate physicians,28 over 25% were unwilling to prescribe PrEP in scenarios with active injection drug use. Thus, further training and efforts to reduce difference in attitudes towards those in this risk category may need to be explored and addressed during residency training.

Overall, barriers in resident practice were similar to those reported for practicing physicians, including knowledge, lack of established protocols, and concern for costs and insurance coverage.7, 11 While the majority of all residents believe PrEP to be safe and efficacious, those with prior training were less likely to be concerned about increased high-risk behaviors.29 Importantly, lack of preceptor support was seen as a barrier, especially for those without prior training. This suggests that physician champions within the practice may facilitate increased PrEP prescribing, as seen in other studies.27, 30

Our study was subject to certain limitations. First, we surveyed five internal medicine programs; our results may not be generalizable across graduate medical education (GME), including community programs and rural locations which may have less exposure to PrEP programs, as well as other specialties who may prescribe PrEP (including Pediatrics, Obstetrics/Gynecology, and Family Medicine). Community and rural programs may be even more impactful on PrEP uptake and the HIV epidemic based on known disparities.31 Other knowledge gaps have been found when discussing family planning and fertility issues surrounding PrEP, and this may impact other GME curricula.32,33,34 We did not survey other health professions training programs such as NP or PA programs that may prescribe PrEP. Second, we elected a convenience sample of residents on listservs. We received only a 35% response rate, which while similar to reported response rates for online surveys,35, 36 increases the potential for bias. The results may also be skewed by response bias; residents with particular interest in the subject matter may be more likely to fill out the survey and have prior knowledge. However, removing this bias would only further highlight deficiencies in training outlined in our findings. While our study focused on provider-related barrier to PrEP, we did not assess knowledge or awareness of patient barriers such as insurance coverage or cost of laboratory requirements, and these have been found to have a profound impact on PrEP uptake.31 Finally, residents were asked to self-report their training, knowledge, and behaviors and PrEP assessment and prescribing were not directly evaluated.

Since the advent of PrEP and reports of increased uptake among both patients and providers, we have seen decreased incidence of HIV.4 As PrEP is an effective and underutilized tool in reducing the burden of HIV, residency programs should be preparing their residents to care for patients in need of PrEP. With an expanding role among primary care providers in prescribing PrEP,7 future internists represent a significant foundation for access to PrEP. Further studies are needed to find the optimal methods to teach trainees about PrEP to improve access to HIV prevention and reduce the incidence of HIV.

References

Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010; 363:2587–2599.

McCormack S, Dunn DT, Desai M, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent the acquisition of HIV-1 infection (PROUD): effectiveness results from the pilot phase of a pragmatic open-label randomized trial. Lancet. 2016; 387(10013):53–60.

US Public Health Service. Preexposure Prophylaxis for the Prevention of HIV Infection in the United States- 2017 Update: A Clinical Practice Guideline. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/prep/cdc-hiv-prep-guidelines-2017.pdf. Accessed December 27, 2018.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Basics: PrEP. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/prep/index.html. Accessed December 27, 2018.

Tang EC, Sobieszczyk ME, Shu E, Gonzales P, Sanchez J, Lama JR. Provider attitudes toward oral preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among high-risk men who have sex with men in Lima, Peru. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2014; 30(5):416–24.

Wilton J, Senn H, Sharma M, Tan DH. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for sexually-acquired HIV risk management: a review. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2015; 7:125–36.

Blumenthal J, Jain S, Krakower D, et al. Knowledge is power! Increased provider knowledge scores regarding pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) are associated with higher rates of PrEP prescription and future intent to prescribe PrEP. AIDS Behav. 2015; 19(5):802–10.

Mimiaga MJ, White JM, Krakower DS, Biello KB, Mayer KH. Suboptimal awareness and comprehension of published preexposure prophylaxis efficacy results among physicians in Massachusetts. AIDS Care. 2014; 26(6):684–93.

Arnold EA, Hazelton P, Lane T, et al. A qualitative study of provider thoughts on implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in clinical settings to prevent HIV infection. PLoS One. 2012; 7(7):e40603.

Sharma M, Wilton J, Seen H, Fowler S, Tan DH. Preparing for PrEP: perceptions and readiness of Canadian physicians for the implementation of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. PLoS One 2014; 9(8):e105283.

Blackstock OJ, Moore BA, Berkenblit GV, et al. A cross-sectional online survey of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis adoption among primary care physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2017; 32(1):62–70.

Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Bauermeister J, Smith H, Conway-Washington C. Minimal awareness and stalled update of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among at risk, HIV-negative, black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015; 29(8):423–29.

Barash EA, Golden M. Awareness and use of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among attendees of a seattle gay pride event and sexually transmitted disease clinic. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2010; 21(11):689–91.

Mehta SA, Silvera R, Bernstein K, Holzman RS, Aberg JA, Daskalakis DC. Awareness of post-exposure prophylaxis in high-risk men who have sex with men in New York City. Sex Transm Infect. 2011; 87(4):344–48.

Smith WR. Evidence for the effectiveness of techniques to change physician behavior. Chest. 2000; 118(2 Suppl):8S–17S.

Grohl R, Wensing M. What drives change? Barriers to and incentives for achieving evidence-based practice. Med J Aust. 2004: 180 (6 Suppl):S57–60.

Sanazaro P. Continuing education, performance assessment, and quality of patient care. Mobius. 1982; 2:34–37.

Berkenblit GV, Sosman JM, Bass M, et al. Factors affecting clinician educator encouragement of routine HIV testing among trainees. J Gen Intern Med. 2012; 27(7):839–44.

Mincey BA, Parkulo MA. Antibiotic prescribing practices in a teaching clinic: Comparison of resident and staff physicians. South Med J. 2001; 94:365–9.

Ryskina KL, Dine CJ, Kim EJ, Bishop ET, Epstein AJ. Effect of attending practice style on general medication prescribing by residents in the clinic setting: an observational study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015; 30(9):1286–93.

Deville C, Hwang WT, Burgos R, Chapman CH, Both S, Thomas CR Jr. Diversity in graduate medical education in the united states by race, ethnicity, and sex, 2012. JAMA Intern Med. 2015; 175(10):1706–08.

Petroll AE, Walsh JL, Owczarzak JL, McAuliffe TL, Bogart LM, Kelly JA. PrEP awareness, familiarity, comfort, and prescribing experience among us primary care providers and HIV specialists. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1256–1267.

White JM, Mimiaga MJ, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Evolution of Massachusetts physician attitudes, knowledge, and experience regarding the use of antiretrovirals for HIV prevention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2012; 26(7):395–405.

Prior M, Guerin M, Grimmer-Somers K. The effectiveness of clinical guideline implementation strategies – a synthesis of systematic review findings. J Eval Clin Pract. 2008; 14(5):888–97.

Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005; 142(4):260–73.

Krakower D, Mayer KH. Engaging healthcare providers to implement HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012; 7(6):593–99.

Silapaswan A, Krakower D, Mayer KH. Pre-exposure prophylaxis: a narrative review of provider behavior and interventions to increase prep implementation in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2017; 32(2):192–198.

Edelman EJ, Moore BA, Calabrese SK, et al. Primary care physician’s willingness to prescribe hiv pre-exposure prophylaxis for people who inject drugs. AIDS Behav. 2017; 21(4):1025–33.

Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2014; 18(9):1712–21.

Marcus JL, Volk JE, Pinder J, et al. Successful implementation of HIV preexposure prophylaxis: lessons learned from three clinical settings. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016; 13(2):116–24.

Goldstein RH, Streed CG Jr, Cahill SR. Being PrEPared - preexposure prophylaxis and HIV disparities. N Engl J Med. 2018; 379(14):1293–1295.

Scherer ML, Douglas NC, Churnet BH, et al. Survey of HIV care providers on management of HIV serodiscordant couples- assessment of attitudes, knowledge and practices. AIDS Care. 2014; 26(11):1435–39.

McMahon JM, Myers JE, Kurth AE, et al. Oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for prevention of HIV in serodiscordant heterosexual couples in the United States: opportunities and challenges. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2014; 28(9):462–74.

Hong JN, Farel CE, Rahangdale L. Pharmacologic prevention of human immunodeficiency virus in women: practical approaches for the obstetrician and gynecologist. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2015; 70(4):284–90.

Kaplowitz MD, Hadlock TD, Levine R. A comparison of web and mail survey response rates. Public Opin Q. 2004; 68 (1): 94–101.

Grava-Gubins I, Scott S. Effects of various methodologic strategies: survey response rates among Canadian physicians and physicians-in training. Can Fam Physician. 2008; 54(10): 1424–30.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amanda Bertram for her help with organizing the survey design and administration.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Marissa Black has stock in Gilead gifted by family in 2014, and all remaining authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Terndrup, C., Streed, C.G., Tiberio, P. et al. A Cross-sectional Survey of Internal Medicine Resident Knowledge, Attitudes, Behaviors, and Experiences Regarding Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis for HIV Infection. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 1258–1278 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04947-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-04947-2