Abstract

Despite policy and practice support to develop and test interventions designed to increase access to quality care among high-need patients, many of these interventions fail to meet expectations once deployed in real-life clinical settings. One example is the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) model, designed to deliver coordinated care. A meta-analysis of PCMH initiatives found mixed evidence of impacts on service access, quality, and costs. Conceptualizing PCMH as a complex health intervention can generate insights into the mechanisms by which this model achieves its effects. It can also address heterogeneity by distinguishing PCMH core functions (the intervention’s basic purposes) from forms (the strategies used to meet each function). We conducted a scoping review to identify core functions and forms documented in published PCMH models from 2007 to 2017. We analyzed and summarized the data to develop a PCMH Function and Form Matrix. The matrix contributes to the development of an explicit theory-based depiction of how an intervention achieves its effects, and can guide decision-support tools in the field. This innovative approach can support transformations of clinical settings and implementation efforts by building on a clear understanding of the intervention’s standard core functions and the forms adapted to local contexts’ characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Primary care settings have been vital to health care transformation efforts to increase the quality of health care services for all patients, including those with co-occurring health and behavioral and social needs.1 Despite their strategic position as the “first line of defense,”2 especially for high-need patients, primary care settings have often failed to provide high-quality care.3, 4 Millions of dollars have been invested in developing and testing interventions designed to transform primary care through innovative health care models that prioritize patient-centered and coordinated care. Yet, many of these interventions frequently fail to meet expectations once they are deployed in real-life clinical settings. A complex health intervention framework5 provides a novel research approach to the study of interventions by elucidating how each intervention works and under what conditions.

Patient-Centered Medical Home Model

For over a decade, policy makers and providers have supported the implementation of the Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) care model to address the multiple health, behavioral, and social needs of patient populations. PCMH is designed to transform the organization and delivery of primary care services through new delivery arrangements characterized by five principles: accessible care, coordinated care, quality care, comprehensive care, and patient-centered care.6

Some research comparing PCMH with standard care shows PCMH advantages such as fewer emergency visits and pediatric ICU admissions and higher service satisfaction.7,8,9,10 On the other hand, multiple large national PCMH evaluations11 have shown mixed evidence of PCMH impacts on service access, quality, and cost.8, 12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19 A meta-analysis of 11 PCMH studies, published between 2008 and 2014, showed that PCMH practices were significantly associated with a 1.5% reduction in specialty visits and an increase in cancer screenings (1.2% for cervical cancer and 1.4% for breast cancer).12 Yet, these researchers also found a lack of association between PCMH and primary care, emergency department and inpatient visits, and several quality measures.12

Since the early 2000s, researchers have attributed mixed PCMH results to weak study designs.20 Specifically, randomized studies lacked power to estimate outcomes, did not account for clustering and organizational performance, and used cross-sectional or short panel data (e.g., 2-year timeline) that did not capture long-term outcomes.20,21,22 These same methodological concerns prevail in recent research and additional suggestions for evaluation include a need to account for the type of PCMH model and its implementation strategies, and high heterogeneity across clinical settings and patient characteristics.12, 15, 18, 19

Although all are relevant, these explanations do not acknowledge that the effectiveness of complex health interventions, like PCMH, lies not only in the presence of strategies and activities but also on the core purposes that those activities are trying to achieve.23 Across studies, there is an underlying assumption that the intervention is sufficiently robust that the researchers can estimate its effect while holding contextual factors constant, and that aspects of the intervention affect a single primary outcome.24 This assumption disregards the fact that PCMH is a flexible multicomponent model implemented within heterogeneous and dynamic settings that continuously reshape the intervention before and during implementation.5, 25 For PCMH, recurring and multiple links among its activities (“forms”) and observed outcomes (Fig. 1) pose a challenge for researchers evaluating this care model.26

THE NEED TO RE-CONCEPTUALIZE PCMH AS A COMPLEX HEALTH INTERVENTION

Recognizing PCMH as a complex health intervention can point us to new research questions, frameworks and study approaches in which researchers, rather than examining the impact of a homogeneous standard blueprint, focus on understanding the mechanisms by which PCMH works, where it works and for whom. In 2011, AHRQ championed this approach for PCMH research.20 Yet, 7 years later, we continue to examine PCMH as a simple standard intervention27 and expect a different outcome.

Key Constructs within the Complex Health Intervention Framework

Complex health interventions are defined as multi-component28 and display the following features: (a) the intervention’s components interact in a summative and synergistic fashion, (b) the individuals delivering and receiving the intervention often exhibit a highly complex set of behaviors, (c) the intervention requires changes at the organizational, workforce and patient levels, (d) outcomes are numerous and variable, and (e) there is often flexibility in how the intervention is implemented on a daily basis.24

In this work, we add to the complex health intervention framework by operationalizing two key constructs. Core functions are the core purposes of the change process that the health intervention seeks to facilitate.23Forms are the specific strategies or activities that may be customized to local contexts and that are needed to carry out the core functions (Fig. 2).

Although overlapping, these distinct constructs need to be considered when implementing and evaluating an intervention. Ideally, an intervention’s core functions and forms align with system and patient needs at the local clinical level to ensure the integrity of the intervention and implementation success. In 2000, the Medical Research Council released guidance on the development, evaluation, and implementation of complex interventions to improve health,24 but the research community has been arguably slow in adopting it. This slow uptake is in part due to a lack of clear definitions and distinctions of key constructs. The concepts of core functions and forms are informed by the work of Penelope Hawe,23, 29 and this paper complements the recently developed Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) standards for studies of complex interventions.30

Concrete Steps to Operationalize Concepts

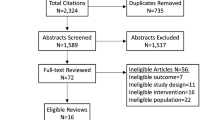

We conducted a scoping review to identify and describe three PCMH domains: (a) patient and system needs addressed by the PCMH intervention, and the (b) the intervention’s core functions,23, 30 and (c) prevailing intervention forms.30 We identified primary care delivery needs, associated core functions and common forms found in published PCMH literature from 2007 to 2017 and in current online sources. We analyzed the literature in two phases to develop the comprehensive PCMH Function and Form Matrix (Table 1).

First, we applied a top-down approach, gathering the results of the national literature review to chart and summarize the data to develop a detailed PCMH Function and Form Matrix (Table 1). Two authors pilot coded two of the articles for each matrix area, and then the full research team made changes to define the literature search strategy and to assess coders’ agreement.

In the second (bottom-up) analysis phase, we held ongoing research team conversations to summarize the information and align each area of the matrix across Table 1. We first crafted core function statements for each PCMH principle based on a comprehensive definition (Fig. 2), the research team’s expertise, and the coded literature (letters A–D in Table 1). Then, we listed all of the PCMH forms gathered from the literature and grouped them into broader categories to facilitate the alignment of each form to a core function. Last, from each form category, we selected concrete examples (Roman numerals in Table 1) to include in the PCMH Function and Form Matrix. Additional details on the methodology used and a comprehensive menu of PCMH forms gathered from the literature are available upon request.

THE PCMH FUNCTION AND FORM MATRIX

The PCMH Function and Form matrix (Table 1) was developed around each of the five PCMH principles. Since the number, name, and definition of PCMH principles vary across sources, we relied on the definitions provided on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) website because this agency is a leader in promoting PCMH policy and research and AHRQ definitions generally encompass those of other sources.6 The PCMH Function and Form Matrix includes three columns: (a) motivating problem or system needs that the care model is seeking to address, (b) standardized core functions, and (c) customized forms. We included one or two representative examples of forms to illustrate this area of the matrix for each core function. Core functions are listed by a capital letter and forms by roman numerals to more easily illustrate the nested nature of this matrix.

More specifically, we included a nested element in the PCMH Function and Form Matrix to identify where two core functions may share the same form(s). This feature is in part illustrated with two of the PCMH principles in Fig. 3.

In this example, for the PCMH accessible care principle, the core function of facilitating patient’s remote access to health consultation and clinical advice (function B in Table 1) is aligned with two PCMH forms: the use of 24/7 patient access to clinical advice or the PCMH team (form II in Table 1) and online patient portals and electronic messaging (form III in Table 1).

APPLICABILITY OF THE FUNCTION AND FORM MATRIX

There are several applications of a complex intervention’s Function and Form Matrix. First, it supports an explicit theory-based depiction of how an intervention achieves its effects, links needs and contextual factors to outcomes, and illustrates how variations in form tie to core functions. Second, it offers a new understanding of a complex intervention’s fidelity as (a) having all functions in place, (b) concrete forms to carry out those functions, and (c) forms that are informed by the needs and characteristics of local contexts. Third, it can be used as a decision-making tool to facilitate better alignment between the intervention’s core functions and expected outcomes. This roadmap can allow health managers and practitioners to assess, in the early stages of implementation, the fit between an intervention’s service arrangements and local context’s needs and characteristics, adapt the intervention to the local clinical setting needs and characteristics, and use this knowledge to strengthen local implementation and evaluation efforts.

Efforts to develop an intervention’s Function and Form Matrix in other settings may pose challenges, including the novelty of this approach and the current state of the intervention’s available policy information and empirical research. In the case of PCMH, the national literature revealed a wide variation in features and functions and forms, likely because terms are not uniformly defined in the literature and in part because the multiple payment models in place across clinical settings and among payers within a single clinic influence the intervention’s characteristics. We addressed this concern by using an ongoing iterative approach between the literature reviewed and expert consultation.

In addition, the development of a core function list may differ for other health interventions that are not based on explicit principles such as PCMH. Nonetheless, we offer a descriptive example that can be used by other researchers as a guide by following a similar iterative and sequential process. Last, matrix development may require expert analysis to identify and apply the concepts of forms and functions, especially if an intervention is not defined by concrete principles like PCMH. Nevertheless, we believe that this approach is generalizable and can be applied to similar health care interventions that meet complex interventions criteria such as human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine completion and stroke prevention.

CONCLUSIONS

We reviewed the PCMH literature to illustrate and apply the concepts of core functions and forms to PCMH as a complex health intervention. This approach advances the complex health intervention field in several ways. First, it provides a framework for developing pragmatic tools that measure key sources of variation stemming from the daily and ongoing dynamics within clinical settings and from the intervention’s operations. Ultimately, by operationalizing and measuring PCMH core functions and forms (i.e., service arrangements), we will be better able to inform its adaptation and implementation, and evaluate impact.

Second, this approach offers a novel avenue for building and improving the “future evidence base” of an intervention like PCMH.20 These efforts align with PCORI’s efforts to define and update methodological standards for patient-centered outcomes research.30 They also follow the AHRQ recommendation to use a complex health intervention framework to evaluate PCMH in order to address mixed results and as a better way to meet the informational needs of policy makers.20

Third, a consolidated Function and Form Matrix offers a useful approach for examining an intervention’s expected outcomes. Disentangling an intervention’s core functions and forms, by developing an intervention’s matrix, can help practitioners access up-to-date evidence in real time and build a repository of local adaptations. This knowledge can help health managers and practitioners better identify the intervention’s standard core functions and the specific forms that will work in their clinical settings and for their patient needs, thus improving overall implementation efforts.

Change history

01 April 2019

This paper was originally published without changes made in the correction process. It has been republished with correction.

References

Institute of Medicine. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. In: Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, ed. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

The Commonwealth Fund. Primary Care: Our First Line of Defense. 2013; http://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/health-reform-and-you/primary-care-our-first-line-of-defense. Accessed November 21, 2018.

Katon W J, Jürgen U, Simon G. Treatment of depression in primary care: where we are, where we can go. Medical Care 2004;42(12):1153–1115.

Solberg LI, Trangle MA, Wineman AP. Follow-up and follow-through of depressed patients in primary care: the critical missing components of quality care. Journal of American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18(6):520–525.

Litaker D, Tomolo A, Liberatore V, Stange KC, Aron D. Using complexity theory to build interventions that improve health care delivery in primary care. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2006;21(S30–34).

AHRQ. The Patient-Centered Medical Home: Strategies to put patients at the center of primary care. 2017; https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/patient-centered-medical-home-strategies-put-patients-center-primary-care. Accessed November 21, 2018.

Farmer JE, Clark MJ, Drewel EH, Swenson TM, Ge B. Consultative care coordination through the medical home for CSHCN: a randomized controlled trial. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2011;15(7):1110–1118.

Friedberg MW, Schneider EC, Rosenthal MB, Volpp KG, Werner RM. Association between participation in a multipayer medical home intervention and changes in quality, utilization, and costs of care. JAMA. 2014;311(8):815–825.

McMillan SS, Kendall E, Sav A, King MA, Whitty JA, Kelly F, Wheeler AJ. Patient-centered approaches to health care: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Medical Care Research and Review. 2013;70(6):567–596.

Mosquera RA, Avritscher EB, Samuels CL, et al. Effect of an enhanced medical home on serious illness and cost of care among high-risk children with chronic illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(24):2640–2648.

CMS. Multi-payer advanced primary care practice. 2018; https://innovation.cms.gov/initiatives/Multi-Payer-Advanced-Primary-Care-Practice/. Accessed November 21, 2018.

Sinaiko AD, Landrum MB, Meyers DJ, Alidina S, Maeng DD, Friedberg MW, Kern LM, Edwards AM, Flieger SP, Houck PR, Peele P. Synthesis of research on patient-centered medical homes brings systematic differences into relief. Health Affairs. 2017;36(3):500–508.

Aysola J, Bitton A, Zaslavsky AM, Ayanian JZ. Quality and equity of primary care with patient-centered medical homes: results from a national survey. Medical Care. 2013;51(1):68–77.

Butcher J, Wolraich M, Gillaspy S, Martin V, Wild R. The impact of a Medical Home for children with developmental disability within a pediatric resident continuity clinic. The Journal of the Oklahoma State Medical Association. 2014;107(12):632–638.

Harder VS, Krulewitz J, Jones C, Wasserman RC, Shaw JS. Effects of patient-centered medical home transformation on child patient experience. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine. 2016;29(1):60–68.

Domino ME, Humble C, Lawrence Jr WW, Wegner S. Enhancing the medical homes model for children with asthma. Medical Care. 2009;47(11):1113–1120.

Golnik A, Scal P, Wey A, Gaillard P. Autism-specific primary care medical home intervention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 2012;42(6):1087–1093.

Han B, Yu H, Friedberg MW. Evaluating the impact of parent-reported medical home status on children's health care utilization, expenditures, and quality: A difference-in-differences analysis with causal inference methods. Health Services Research. 2017;52(2):786–806.

Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, Bettger JP, Kemper AR, Hasselblad V, Dolor RJ, Irvine RJ, Heidenfelder BL, Kendrick AS, Gray R. et al. The patient-centered medical home: a systematic review. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2013;158(3):169–178.

Peikes D, Zutshi A, Genevro J, Smith K, Parchman M, Meyers D. Early evidence on the patient-centered medical home. American Journal of Managed Care. 2012;18:105–6.

Berman S, Rannie M, Moore L, Elias E, Dryer LJ, Jones MD. Utilization and costs for children who have special health care needs and are enrolled in a hospital-based comprehensive primary care clinic. Pediatrics. 2005;115(6):e637-e642.

Cooley WC, McAllister JW, Sherrieb K, Kuhlthau K. Improved outcomes associated with medical home implementation in pediatric primary care. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):358–364.

Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2004;328(7455):1561.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337:a1655.

Leykum LK, Pugh J, Lawrence V, et al. Organizational interventions employing principles of complexity science have improved outcomes for patients with Type II diabetes. Implementation Science. 2007;2(1):28.

Schwenk TL. The patient-centered medical home: one size does not fit all. JAMA. 2014;311(8):802–803.

Petticrew M. When are complex interventions ‘complex’? When are simple interventions ‘simple’? European Journal of Public Health. 2011;21(4):3970–3398.

Guise JM, Chang C, Viswanathan M, et al. Systematic Reviews of Complex Multicomponent Health Care Interventions [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2014; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK194846/. Accessed 21 November 2018.

Shiell A, Hawe P, Gold L. Complex interventions or complex systems? Implications for health economic evaluation BMJ: British Medical Journal. 2008;336(7656):1281–1283.

PCORI. Standards for Studies of Complex Interventions (SCI). 2018; https://www.pcori.org/sites/default/files/PCORI-Methodology-Report.pdf. Accessed November 21, 2018.

Oregon Health Authority. Patient-Centered Primary Care Home Program: 2017 Recognition Criteria, technical specifications and reporting guide. 2017;2:1–144. https://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/dsi-pcpch/Documents/TA-Guide.pdf. Accessed November 21, 2018.

Ackroyd SA, Wexler DJ. Effectiveness of diabetes interventions in the patient-centered medical home. Current Diabetes Reports. 2014;14(3):471–480.

Chaumont VM. Patient-Centered Medical Home Pilot: Final Report. 2013, November. https://www.pcpcc.org/resource/final-report-patient-centered-medical-home-pilot. Accessed November 21, 2018.

Maine PCMH Pilot. PCMH 2013 core expectations: Minimum Requirements. 2013:4. https://www.mainequalitycounts.org/image_upload/Maine_PCMH_Pilot_MAPCP_Extension_MOA_Appdx_C_Reporting_Expectations_Nov2014.pdf Accessed November 21, 2018.

NCQA. PCMH Reconition Process: Becoming a PCMH. Patient Centered Medical Home PCMH 2017; http://www.ncqa.org/programs/recognition/practices/patient-centered-medical-home-pcmh/getting-recognized/get-started/process-becoming-a-pcmh. Accessed November 21, 2018.

Alexander JA, Paustian M, Wise CG, et al. Assessment and measurement of patient-centered medical home implementation: the BCBSM experience. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2013;11(Suppl 1):S74-S81.

Fix GM, Asch SM, Saifu HN, Fletcher MD, Gifford AL, Bokhour BG. Delivering PACT-principled care: are specialty care patients being left behind? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2014;29(2):695–702.

Chang A, Bowen JL, Buranosky RA, Frankel RM, Ghosh N, Rosenblum MJ, Thompson S, Green ML. Transforming primary care training—patient-centered medical home entrustable professional activities for internal medicine residents. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2013;28(6):801–809.

Paustian ML, Alexander JA, El Reda DK, Wise CG, Green LA, Fetters MD. Partial and incremental PCMH practice transformation: implications for quality and costs. Health Services Research. 2014;49(1):52–74.

New York State Department of Health. NYS health home provider qualification standards for chronic medical and behavioral health patient populations. September, 2017:1. https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/program/medicaid_health_homes/provider_qualification_standards.htm. Accessed November 21, 2018.

Detmer D, Bloomrosen M, Raymond B, Tang P. Integrated personal health records: transformative tools for consumer-centric care. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2008;8(1):45.

Acknowledgments

Ms. Crystal Villalpando made valuable contributions to the literature searches and initial classification of the literature. We would also like to thank Laura Esmail, PhD, MSc, and Barbara J. Turner, MD, for reviewing drafts of this manuscript.

Funding

This project was in part funded by an internal grant from the Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work, University of Southern California, Los Angeles.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Perez Jolles, M., Lengnick-Hall, R. & Mittman, B.S. Core Functions and Forms of Complex Health Interventions: a Patient-Centered Medical Home Illustration. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 1032–1038 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4818-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4818-7