Abstract

Background

Studies suggest that involving students in patient education can contribute to the quality of care and medical education. Interventions and outcomes in this field, however, have not yet been systematically reviewed. The authors examined the scientific literature for studies on interventions and outcomes of student-provided patient education.

Methods

Four databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, ERIC, PsycINFO) were searched for studies reporting patient education, undergraduate medical students, and outcomes of patient education, published between January 1990 and October 2015. Facilitators of and barriers to educational interventions were assessed using the Learning Transfer System Inventory. The learning yield, impact on quality of care, and practical feasibility of the interventions were rated by patients, care professionals, researchers, and education professionals.

Results

The search resulted in 4991 hits. Eighteen studies were included in the final synthesis. Studies suggested that student-provided patient education improved patients’ health knowledge, attitude, and behavior (nine studies), disease management (three studies), medication adherence (one study), and shared decision-making (one study). In addition, involving students in patient education was reported to enhance students’ patient education self-efficacy (four studies), skills (two studies), and behavior (one study), their relationships with patients (two studies), and communication skills (two studies).

Discussion

Our findings suggest that student-provided patient education—specifically, student-run patient education clinics, student-provided outreach programs, student health coaching, and clerkships on patient education—has the potential to improve quality of care and medical education. To enhance the learning effectiveness and quality of student-provided patient education, factors including professional roles for students, training preparation, constructive supervision, peer support on organizational and individual levels, and learning aids should be taken into account. Future research should focus on further investigating the effects found in this study with high-level evidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Healthcare is shifting towards person-centered care and patient empowerment, and physician–patient relations are evolving towards shared decision-making.1 Part of the effort to improve care outcomes involves educating patients with regard to disease and treatment processes through the use of various approaches aimed at improving self-care,2 health literacy,3 treatment adherence,4 and health outcomes.5 – 8 Along with patient empowerment, medical education is shifting towards professional roles for students in patient care.9 Undergraduate students are progressively involved in care practice during longitudinal clerkships,10 , 11 in service-learning education,12 , 13 and in student-run clinics.14 , 15 To enable medical students to play a more substantial and meaningful role in care practice, new educational strategies need to be explored.9

Workplace learning among medical students in care practice at an early stage of medical education enhances students’ professional identity and attitude, team experience and skills, and their ability to perform tasks.16 Moreover, student-provided patient education is hypothesized to benefit both patients and students.17 Various examples have been reported on involving undergraduate healthcare students in providing health promotion interventions.18 , 19

Despite the above-mentioned examples and effects, no reviews have yet systematically assessed the specific interventions and outcomes that have been reported when undergraduate medical students are involved in patient education. Our scoping review examines the scientific literature for studies on interventions and outcomes of student-provided patient education and evaluates ways in which these interventions can benefit patient care and medical education.

METHODS

We searched four databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, ERIC, PsycINFO) for studies on student-provided patient education, published between January 1990 and October 2015, using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

The search strategy combined two themes: patient education and undergraduate medical students, with patient-centered outcomes. The outcome measures were based on important elements of patient-centered care: patient satisfaction, self-care, health literacy, treatment compliance, and health attitudes, patient empowerment, student communication skills, shared decision-making, and relations between (future) care professionals and patients.

We removed duplicates automatically using EndNote (version 7.2; Clarivate Analytics, New York, NY, USA). Screening and inclusion of records was conducted independently by two researchers (TV, TB). We screened titles and abstracts to exclude records not describing both patient education and undergraduate medical students. Full-text assessment was performed to include studies that specifically studied a student-provided patient education intervention that targeted real patients and was aimed at the outcomes used in the search strategy. We discussed disagreements on screening and inclusion until agreement was reached. References of included studies were checked for other relevant studies.

We determined study quality using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, which is specifically aimed at assessing the quality of public health studies.20 Two researchers (TV, TB) independently evaluated study quality and resolved disagreements through discussion in order to reach final study quality ratings. The tool guidelines state that any study with two or more weak scores on subcategories is considered to have a weak overall score. Since most of the studies in our review had low evidence levels and low study quality, we chose to modify the overall rating method by using an averaging of ratings on subcategories to be able to differentiate between ratings on study quality.

Included studies were characterized by one researcher (TV) with regard to intervention method, outcomes that were concordant with the outcomes of the search strategy, the subject of patient education, the patient target group, the educational stage of the medical students involved, the care setting of patient education, and the study location. The four-level Kirkpatrick model was used to categorize the level of effects (experiences, learning, behavior, and organizational impact) of the interventions on both patients and students.21

Two patients, two care professionals, and two researchers, all working in the field of patient empowerment and medical education, rated the studies on a scale of 1 to 10 in terms of their impact on quality of care and their practical feasibility. Five education professionals in medical education rated the studies on a scale of 1 to 10 on the basis of learning yield and practical feasibility. In addition, an overall score was determined by all experts based on study quality, intervention characteristics, and outcomes. Ratings were based on their individual experience and expertise in medical education and quality of care. To guide the rating process, the experts received a document describing the intervention methods, outcomes, and quality of the studies, as presented in Table 1, and a guideline which included the goal of rating the studies, a description of information presented in the table, and definitions of quality of care, learning yield, and practical feasibility. Higher- and lower-than-average scores were used to categorize and compare the interventions. The intra-class correlation coefficient of expert rating groups was calculated using SPSS software (version 22; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) in a two-way mixed model to determine rating consistency.

Finally, we used a customized assessment tool based on the Learning Transfer System Inventory (LTSI) to assess facilitators of and barriers to student-provided patient education. The LTSI is a validated model that describes factors influencing the transfer of a training intervention on the individual.40 Based on this model, we formulated facilitators and barriers in practice-based learning. Qualitative assessment of the reported facilitators and barriers was performed by two researchers (TV, CF) by coding study elements that were in concordance with the LTSI-based assessment tool using ATLAS.ti (version 7.1.5; Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Differences between coded facilitators and barriers were discussed to reach agreement.

RESULTS

Search Results

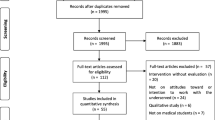

The search resulted in 4991 records. After removing duplicates, 3842 titles and abstracts were screened for relevance, leading to the exclusion of 3701 studies. Full-text assessment was performed in 141 studies to determine eligibility, resulting in the inclusion of 17 studies in the final synthesis. A search of the references of the included studies revealed one additional relevant study, which was added to the synthesis (Fig. 1). In total, five non-randomized controlled trials,22 , 25 , 34 , 35 , 38 four uncontrolled before-and-after studies,26 , 30 , 33 , 37 eight post-intervention survey or interview studies,23 , 24 , 27 – 29 , 31 , 32 , 39 and one case series study36 were included.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the number of records and studies identified during the search process, screened for relevance, assessed for eligibility and included in the synthesis. Reasons for exclusion of records or studies during the screening and eligibility process were categorized per group and are visualized per group and in total

Interventions and Outcomes

Geographically, 12 studies were performed in the USA,22 – 24 , 26 – 28 , 30 – 32 , 36 – 38 three in the European Union,25 , 34 , 39 and one each in Canada,29 New Zealand,35 and Singapore.33

The studies described the following: medical students providing patient education during clerkships aimed at learning to provide patient education;26 – 28 , 31 , 35 medical students providing patient education courses or other types of teaching to patients and family members;24 , 25 , 29 , 30 , 32 medical students supporting patients in the context of treatment;22 , 38 , 39 medical students performing patient education to reach underserved communities;23 , 33 , 37 and medical students providing patient education in a student-run clinic or teaching clinic34 , 36 (Table 1).

The included studies involved undergraduate medical students at different stages of medical education. Several studies did not describe the medical students’ educational stage.22 , 24 , 25 , 30 , 32 , 33

Most involved student participation in providing patient education in primary care.24 , 26 – 28 , 31 , 36 , 37 Others involved medical students in the community,23 , 29 , 32 , 33 in the surgical department,38 , 39 the emergency department,22 , 25 in psychiatry,30 , 38 or in rural practice.35 Specifically, medical students provided patient education with regard to diabetes,23 , 26 – 28 , 31 – 33 hypertension,23 , 28 , 32 , 33 , 37 mental illnesses,28 , 32 arthritis,28 cardiac arrest,25 communicating with care professionals,29 treatment plans and options,38 surgical procedures,39 discharge instructions,22 use of digital tools,24 medication,33 , 36 disease-related lifestyle issues,30 , 32 , 37 and self-care.34

Nine studies reported on patient satisfaction.22 – 25 , 27 , 29 , 31 , 33 , 37 Aspects of patient-centered care were reported to be improved in student-provided patient education.41 , 42 Six studies reported increased self-reported health or disease knowledge,25 , 27 , 32 , 37 , 39 which was significant in one study (p < 0.006).34 One study reported enhanced health or disease knowledge (p < 0.02).30 One study reported improved self-reported confidence with regard to self-management.25 Another study reported improved shared decision-making.34 Two studies reported improved self-reported communication skills,32 , 33 and two reported improved student–patient relations.33 , 38

In terms of health-related outcomes, four studies reported a change in patients’ self-reported behavior or attitude toward their disease.24 , 27 , 29 , 37 Three studies described improved disease management36 (two studies with significant differences, p < 0.001 and p < 0.03, respectively).33 , 37 Another study reported improved self-reported medication adherence (p < 0.01).37

Student outcomes of student-provided patient education were described at Kirkpatrick levels 1–3. Three studies showed student satisfaction (level 1).28 , 33 , 38 Four studies reported enhanced self-reported patient education self-efficacy (level 2).26 , 33 , 35 , 39 Two studies reported positive effects in terms of improved self-reported patient education skills.28 , 38 In addition, two studies reported improved communication skills.32 , 33 One study described a self-reported change in students’ patient education behavior (level 3).38

Study Quality Assessment

Six studies had moderate scores on study quality,22 , 25 , 26 , 33 , 34 , 38 and 12 studies had weak scores23 , 24 , 27 – 32 , 35 – 37 , 39 (Table 2). Weak quality ratings were the result of the following factors: uncertainty about representative participants in six studies;23 , 28 , 30 , 32 , 35 , 37 less than 60% participation among selected individuals in four studies23 , 25 , 32 , 35; weak study design in nine studies;23 , 24 , 27 – 29 , 31 , 32 , 36 , 39 study participant characteristics were not investigated in depth or compared to the general population in 15 studies;23 , 24 , 26 – 33 , 35 – 39 important baseline differences between groups in two studies;35 , 38 no reported use of valid or reliable measurement tools in 16 studies;22 – 33 , 35 , 36 , 38 , 39 and no reports of withdrawals or dropouts in three studies.25 , 35 , 38 In total, four non-randomized controlled trials22 , 25 , 34 , 38 and two uncontrolled before-and-after studies26 , 33 had moderate scores on study quality.

Expert Ratings

Patients, care professionals, and researchers in the field of patient empowerment expected that various interventions would have a higher-than-average impact on quality of care,22 , 25 , 27 – 29 , 32 – 34 , 36 , 37 whereas eight studies were expected to have a lower-than-average impact on quality of care. Education professionals rated seven studies with higher-than-average learning yield23 , 25 , 28 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 37 and 11 studies with lower-than-average learning yield. All experts rated seven studies with a higher-than-average overall score,24 , 25 , 28 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 37 and 11 studies with a lower-than-average overall score (Table 3).

Only one intervention, which involved medical students providing cardiac arrest courses to patients and family members, received high ratings on learning yield, quality of care, and practical feasibility.25 Five interventions—student-provided clinics and programs for diverse patient groups, a summer clerkship aimed at patient education, and student health coaching for uninsured patients—were given high ratings on learning yield and impact on quality of care, but were rated as having low practical feasibility.28 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 37 One intervention in which students provided discharge instructions was rated as having a high impact on quality of care and practical feasibility, but low learning yield.22 In addition, three interventions—providing diabetes foot-care education during a preceptorship, a student-provided course on health literacy, and a student-provided course on communication with physicians—were rated as having a high impact on quality of care, low learning yield, and low practical feasibility.27 , 29 , 32 One intervention, involving a student-provided patient education health fair, was rated as having a higher learning yield but low impact on quality of care and practical feasibility.23 Low learning yield, low impact on quality of care, and high practical feasibility were found in four interventions: students providing follow-up telephone calls after discharge, providing enhanced communication with patients regarding informed consent for surgery, assisting patients in using the Internet for patient education, and providing diabetes foot-care education.24 , 26 , 38 , 39 Three interventions had low ratings on all aspects: students providing wellness classes for inpatients with psychotic disorders, students providing diabetes foot-care education, and students providing patient education in the rural community.30 , 31 , 35

The consistency among ratings of (1) education professionals on learning yield; (2) patients, care professionals, and researchers on impact on quality of care; and 3) all stakeholders on overall score was 0.548–0.795, and was significant (P < 0.05). The intra-class correlation coefficient of expert ratings on the practical feasibility of the interventions, on the contrary, was 0.511 and was non-significant.

Facilitators and Barriers

An in-depth assessment of the studies showed that in most interventions, students were prepared through orientation or training sessions before their practical experience with real patients.23 , 25 – 29 , 31 , 37 – 39 Written or oral feedback or support provided by supervisors, fellow students, or patients were also reported to facilitate the effectiveness of patient education.26 , 27 , 31 – 36 , 39 Peer support from other students was provided in most interventions, at the individual or organizational level, facilitating the students’ learning achievements.23 , 29 , 33 , 34 , 36 Various learning aids, such as leaflets, were provided to students to enhance learning opportunities.26 , 27 , 31 , 37 A transfer design approach was applied in most studies, in which the training program resembled the future job and the students were part of the treatment team in a professional role, which facilitated learning effectiveness23 , 26 – 29 , 32 – 34 , 36 , 37 , 39 (Table 4).

Preselecting motivated students, e.g., by voluntary application to the learning module or course, was discussed in the studies as being both a facilitator and barrier: motivated students were expected to perform better;23 , 28 , 33 students who regarded the training program as too voluntary, on the contrary, were reported to perform less well.26 , 33

One study reported that students felt they had not been able to contribute to patient care by providing patient education.38 Another mentioned that supervisors did not recognize the students’ skills in patient education or did not acknowledge the importance of students performing or practicing patient education.26 Yet another study reported that students did not have enough time to practice patient education on real patients, over and above other curricular activities.37

DISCUSSION

Our findings suggest that involving undergraduate medical students in patient education has the potential to improve the quality of care and medical education. The included studies reported that student-provided patient education enhanced patient health or disease knowledge, health attitude, health behavior, medication adherence, disease management, and shared decision-making. In addition, enabling students to provide patient education was reported to enhance students’ patient education skills, patient education self-efficacy, patient education behavior, relations with patients, and communication skills. These findings support evidence that students greatly appreciate and benefit from practice-based patient interaction.14 , 43

Student-run patient education clinics, student-provided outreach programs, student health coaching, and clerkships on patient education, in particular, were rated by experts as having a higher-than-average learning yield and impact on quality of care, and thus should be implemented to improve the quality of care and medical education.28 , 33 , 34 , 36 , 37

The World Health Organization has defined six dimensions of quality of care: effectiveness, efficacy, accessibility, patient-centeredness, equity, and safety.44 The current review indicates that students can contribute to effective, accessible, and equitable healthcare. The interventions also led to improvements in important contributors to patient-centeredness of care, including patients’ health knowledge, self-management, shared decision-making, communication skills of (future) care professionals, and relations between patients and students.41 , 42 In addition, combining student-provided patient education with medical education can enhance the efficiency of care and medical education.

From a student perspective, student-provided patient education can enhance students’ self-efficacy in patient encounters in general, and it enables students to recognize their independence in assisting patients and can help them feel that they are capable of contributing to patient care. Peer support and collaboration among different levels of students can enhance teamwork skills and facilitate the development of other skills relevant for physicians, such as leadership and coaching. Moreover, student-provided patient education can provide students with further insight regarding their career perspective.

Medical students should be prepared for providing patient education in practice through the use of training or orientation sessions to improve the quality of the education they provide. Involving peers, preceptors or other supervisors, and patients in supervision or provision of feedback to students enhances their self-efficacy and gives them personal recognition for contributing to patient care.45 In line with the practice of workplace pedagogy, students in clinically embedded approaches should be included in the treatment team as equal members in order to enhance their independence and value in providing care.46 Finally, student peer support, such as the involvement of students from different stages of medical education, contributes to training effectiveness, for example, by improving students’ teamwork skills.33

Despite the high impact on quality of care and medical education, the practical feasibility of more complex interventions, such as student-run patient education clinics, outreach programs, student health coaching, and clerkships on patient education, was rated low by experts. Other interventions, such as medical student involvement in providing courses on cardiac or respiratory arrest,25 communication with doctors,29 or health literacy,32 or students providing discharge instructions to patients,22 may be practically more feasible, and were rated as having a high impact on quality of care. Other ratings by experts on practical feasibility in this review can be used to guide future practices and research in the field of medical education.

Limitations

As an important aspect of medical education focuses on specialized care, we configured our search strategy for patient education studies (defined as educating or counseling people with a disease) rather than health promotion studies (defined as preventive education for the general public). Though we found records addressing health promotion performed by medical students, we excluded studies that did not address disease-related issues.

The search strategy used in this study was aimed at patient-centered outcomes of patient education. Improving health status with patient education is a subject of debate.47 Given that our review shows that disease management is enhanced with student-provided patient education, other studies may show that health status is improved as well.48

Finally, since our search was limited to the scientific literature, examples of integrating patient education and medical education as reported in the gray literature are not described in this review.

Future Research

In light of the low to moderate quality of the studies included in this review, future research should examine the effects of student-provided patient education with high-level evidence, such as randomized controlled trials. Specifically, the evidence level was low in studies on health-related outcomes of student-provided patient education, such as patients’ disease attitude, medication adherence, and disease management, making them difficult to interpret. Future research should examine these impacts in high-quality studies.

In addition, since most outcomes in the selected studies were self-reported, social desirability bias may have influenced the results; future research should use validated and reliable methods such as observational research, (focus group) interviews, or knowledge and attitude questionnaires to improve the validity of effect evaluations.

Though other studies reported improved patient outcomes with student-provided patient education, high-quality studies were largely aimed at examining the impact on the quality of medical education. Since our findings suggest that both patients and students benefit from student-provided patient education, future studies should simultaneously assess these effects on both patients and students.

In the evaluations of effects in the current review, the greatest emphasis was placed on learner satisfaction and learning goals, such as obtaining knowledge or changing attitudes. Future research should also investigate the effects on students’ patient education behavior. Moreover, although it is expected that student-provided patient education can impact the practice of care and medical education, the impact at an organizational level was not investigated; such effects should be examined in future studies. In addition, various other effects of student-provided patient education were described, such as improved leadership skills and role independence, or enhanced career perspectives. Future studies should further investigate these effects on students.

Finally, most studies performed a before-and-after evaluation and missed the opportunity to examine whether the effects were sustained. Future studies should examine the longer-term effects on patients and students.

CONCLUSIONS

The integration of patient education into medical education has the potential to improve quality of care and enhance medical education. In particular, student-run patient education clinics, student-provided outreach programs, student health coaching, and clerkships on patient education can contribute to quality of care and medical education and should be implemented in care practice and medical education.

Our review provides an extensive overview of ways that student-provided patient education can benefit quality of care and medical education. Given the low to moderate quality of the studies reviewed, further research is needed on the effects of student-provided patient education. Such future studies should (1) provide high-quality evidence of the effects on both patients and students; (2) further examine effects such as the impact on leadership skills, role independence, and career perspectives among students; 3) investigate the long-term effects on patients and students; 4) examine the impact on clinical and educational practice; and 5) further investigate the effects on health-related outcomes.

References

Hoving C, Visser A, Mullen PD, van den Borne B. A history of patient education by health professionals in Europe and North America: from authority to shared decision making education. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(3):275–81.

Gay C, Chabaud, A, Guilley, E, Coudeyre, E. Educating patients about the benefits of physical activity and exercise for their hip and knee osteoarthritis. Systematic literature review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med. 2016;59(30:174–83.

Clement S, Ibrahim S, Crichton N, Wolf M, Rowlands G. Complex interventions to improve the health of people with limited literacy: A systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;75(3):340–51.

Arthurs G, Simpson J, Brown A, Kyaw O, Shyrier S, Concert CM. The effectiveness of therapeutic patient education on adherence to oral anti-cancer medicines in adult cancer patients in ambulatory care settings: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(5):244–92.

Lopez-Vargas PA, Tong A, Howell M, Craig JC. Educational Interventions for Patients With CKD: A Systematic Review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2016;68(3):353–70.

Brown WA, Burton PR, Shaw K, Smith B, Maffescioni S, Comitti B, et al. A Pre-Hospital Patient Education Program Improves Outcomes of Bariatric Surgery. Obe Surg. 2016;26(9):2074–81.

Pillay J, Armstrong MJ, Butalia S, Donovan LE, Sigal RJ, Chordiya P, et al. Behavioral Programs for Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(11):836–47.

Pillay J, Armstrong MJ, Butalia S, Donovan LE, Sigal RJ, Vandermeer B, et al. Behavioral Programs for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(11):848–60.

Curry RH. Meaningful roles for medical students in the provision of longitudinal patient care. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2335–6.

Thistlethwaite JE, Bartle E, Chong AA, Dick ML, King D, Mahoney S, et al. A review of longitudinal community and hospital placements in medical education: BEME Guide No. 26. Med Teach. 2013;35(8):e1340–64.

Walters L, Greenhill J, Richards J, Ward H, Campbell N, Ash J, et al. Outcomes of longitudinal integrated clinical placements for students, clinicians and society. Med Educ. 2012;46(11):1028–41.

Stewart T, Wubbena ZC. A systematic review of service-learning in medical education: 1998-2012. Teach Learn Med. 2015;27(2):115–22.

Hunt JB, Bonham C, Jones L. Understanding the goals of service learning and community-based medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2011;86(2):246–51.

Schutte T, Tichelaar J, Dekker RS, van Agtmael MA, de Vries TP, Richir MC. Learning in student-run clinics: a systematic review. Med Educ. 2015;49(3):249–63.

Simpson SA, Long JA. Medical student-run health clinics: Important contributors to patient care and medical education. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(3):352–6.

Smith SE, Tallentire VR, Cameron HS, Wood SM. The effects of contributing to patient care on medical students’ workplace learning. Med Educ. 2013;47(12):1184–96.

Self TH, Economides AK, Airee R, Clark DE. Educating inner-city patients with asthma: a compelling opportunity for volunteer service by health science center students. J Asthma. 2004;41(1):1–3.

Stuhlmiller CM, Tolchard B. Developing a student-led health and wellbeing clinic in an underserved community: collaborative learning, health outcomes and cost savings. BMC nursing. 2015;14(1):32.

Isaacs D, Riley AC, Prasad-Reddy L, Castner R, Fields H, Harper-Brown D, et al. Jazzin’ Healthy: Interdisciplinary Health Outreach Events Focused on Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;1–10.

Effective Public Health Practice Project. Quality Assessment Tool For Quantitative Studies. http://www.ephpp.ca/index.html. Effective Public Health Practice Project; 1998. Accessed March 30, 2017.

Kirkpatrick DL. Techniques for Evaluating Training-Programs. Train Dev J. 1979;33(6):78–92.

Isaacman DJ, Purvis K, Gyuro J, Anderson Y, Smith D. Standardized Instructions - Do They Improve Communication of Discharge Information from the Emergency Department. Pediatrics. 1992;89(6):1204–8.

Fournier AM, Harea C, Ardalan K, Sobin L. Health fairs as a unique teaching methodology. Teach Learn Med. 1999;11(1):48–51.

Helwig AL, Lovelle A, Guse CE, Gottlieb MS. An office-based Internet patient education system a pilot study. J Fam Practice. 1999;48(2):123–7.

Kliegel A, Sheinecker W, Sterz F, Eisenburger P, Holzer M, Laggner AN. The attitudes of cardiac arrest survivors and their family members towards CPR courses. Resuscitation. 2000;47(2):147–54.

Nieman LZ, Foxhall LE, Groff J, Cheng L. Applying practical preventive skills in a preclinical preceptorship. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):478–83.

Sifuentes F, Chang L, Nieman LZ, Foxhall LE. Evaluating a diabetes foot care program in a preceptorship for medical students. Diabetes Educ. 2002;28(6):930.

Crosson J, Heaton CJ, Boyd L. The Summer Assistantship in Patient Education: A preclinical preceptorship. Fam Med. 2003;35(1):15–7.

Towle A, Godolphin W, Van Staalduinen S. Enhancing the relationship and improving communication between adolescents and their health care providers: A school based intervention by medical students. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62(2):189–92.

Wirshing DA, Smith RA, Erickson ZD, Mena SJ, Wirshing WC. A wellness class for inpatients with psychotic disorders. J Psychiatr Pract. 2006;12(1):24–9.

Nieman LZ. A preclinical training model for chronic care education. Med Teach 2007;29(4):391–3.

Hess J, Whelan JS. Making health literacy real: adult literacy and medical students teach each other. J Med Libr Assoc. 2009;97(3):221–4.

En WL, Koh GCH, Lim VKG. Caring for Underserved Patients Through Neighborhood Health Screening: Outcomes of a Longitudinal, Interprofessional, Student-Run Home Visit Program in Singapore. Acad Med. 2011;86(7):829–39.

Hallin K, Henriksson P, Dalen N, Kiessling A. Effects of interprofessional education on patient perceived quality of care. Med Teach 2011;33(1):e22–6.

Rudland J, Tordoff R, Reid J, Farry P. The clinical skills experience of rural immersion medical students and traditional hospital placement students: a student perspective. Med Teach. 2011;33(8):e435–9.

Berman R, Powe C, Carnevale J, Chao A, Knudsen J, Nguyen A, et al. The crimson care collaborative: a student-faculty initiative to increase medical students’ early exposure to primary care.Acad med. 2012;87(5):651–5.

Leung LB, Busch AM, Nottage SL, Arellano N, Glieberman E, Busch NJ, et al. Approach to antihypertensive adherence: a feasibility study on the use of student health coaches for uninsured hypertensive adults. Behav Med. 2012;38(1):19–27.

Saba GW, Chou CL, Satterfield J, Teherani A, Hauer K, Poncelet A, et al. Teaching patient-centered communication skills: a telephone follow-up curriculum for medical students. Med Educ Online. 2014;19:22522.

Chiapponi C, Meyer F, Jannasch O, Arndt S, Stubs P, Bruns CJ. Involving Medical Students in Informed Consent: A Pilot Study. World J Surg. 2015;39(9):2214–9.

Holton E, Bates, RA, Ruona, WEA. Development of a generalized learning transfer system inventory. Hum Resour Dev Q. 2000;11(4):333–60.

Health Foundation. Why shared decision making and self-management support are important http://personcentredcare.health.org.uk/person-centred-care/shared-decision-making-0/commissioning/why-shared-decision-making-and-self. Health Foundation; 2016. Accessed March 30, 2017.

Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—the pinnacle of patient-centered care. New Engl J of Med. 2012;366(9):780–1.

Sheu LC, Zheng P, Coelho AD, Lin LD, O’Sullivan PS, O’Brien BC, et al. Learning Through Service: Student Perceptions on Volunteering at Interprofessional Hepatitis B Student-run Clinics. J Cancer Educ. 2011;26(2):228–33.

World Health Organization Quality of Care: A process for making strategic choices in health systems. World Health Organization, 2006.

Cheetham GC. How professionals learn in practice: an investigation of informal learning amongst people working in professions. Journal of European industrial training. 2001;25(5):247–92.

Billett S. Toward a workplace pedagogy: Guidance, participation, and engagement. Adult Educ Quart. 2002;53(1):27–43.

Riemsma RP, Taal E, Kirwan JR, Rasker JJ. Patient education programmes for adults with rheumatoid arthritis. BMJ. 2002;325(7364):558–9.

Gorrindo P, Peltz A, Ladner TR, Reddy I, Miller BM, Miller RF, et al. Medical Students as Health Educators at a Student-Run Free Clinic: Improving the Clinical Outcomes of Diabetic Patients. Acad Med. 2014;89(4):625–31.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our expert panel of patients, researchers, care professionals, and education professionals for assessing the interventions and outcomes of the studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funders

Unconditional grant from the Radboudumc Health Academy.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Vijn, T.W., Fluit, C.R.M.G., Kremer, J.A.M. et al. Involving Medical Students in Providing Patient Education for Real Patients: A Scoping Review. J GEN INTERN MED 32, 1031–1043 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4065-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-4065-3