Abstract

Background

Rationing is a controversial topic among US physicians. Understanding their attitudes and behaviors around rationing may be essential to a more open and sensible professional discourse on this important but controversial topic.

Objective

To describe rationing behavior and associated factors among US physicians.

Design

Survey mailed to US physicians in 2012 to evaluate self-reported rationing behavior and variables related to this behavior.

Setting

US physicians across a full spectrum of practice settings.

Participants

A total of 2541 respondents, representing 65.6 % of the original mailing list of 3872 US addresses.

Interventions

The study was a cross-sectional analysis of physician attitudes and self-reported behaviors, with neutral language representations of the behaviors as well as an embedded experiment to test the influence of the word “ration” on perceived responsibility.

Main Outcome Measures

Overall percentage of respondents reporting rationing behavior in various contexts and assessment of attitudes toward rationing.

Key Results

In total, 1348 respondents (53.1 %) reported having personally refrained within the past 6 months from using specific clinical services that would have provided the best patient care, because of health system cost. Prescription drugs (n = 1073 [48.3 %]) and magnetic resonance imaging (n = 922 [44.5 %]) were most frequently rationed. Surgical and procedural specialists were less likely to report rationing behavior (adjusted odds ratio [OR] [95 % CI], 0.8 [0.9–0.9] and 0.5 [0.4–0.6], respectively) compared to primary care. Compared with small or solo practices, those in medical school settings reported less rationing (adjusted OR [95 % CI], 0.4 [0.2–0.7]). Physicians who self-identified as very or somewhat liberal were significantly less likely to report rationing (adjusted OR [95 % CI], 0.7 [0.6–0.9]) than those self-reporting being very or somewhat conservative. A more positive opinion about rationing tended to align with greater odds of rationing.

Conclusions

More than one-half of respondents engaged in behavior consistent with rationing. Practicing physicians in specific subgroups were more likely to report rationing behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Research has shown that physicians believe that they bear some responsibility for controlling health care costs, but tend to think that greater responsibility should be shouldered by others.1 Physicians have also more typically expressed the belief that they have a greater obligation to do whatever is needed for their patients than to be the primary agents for withholding health care resources for the sake of society.1 , 2

Studies have tended to focus more on physician attitudes regarding allocation of costly resources than on physician behavior. While attitudes might be a primary driver of behavior in clinical practice, this behavior may not be exclusively a function of a physician’s stated beliefs, particularly because these beliefs pertain to the sensitive topic of rationing. Little is known about self-reported rationing behavior among US physicians.

The present paper describes self-reported behavior of a random sample of US physicians consistent with a behavioral definition of rationing, and analyzes its association with demographic and practice factors. We also report an experiment designed to test for empirical evidence of social desirability bias surrounding the term “ration.” Finally, we compare self-reported rationing behavior to self-reported attitudes toward the appropriateness of rationing.

METHODS

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and the Office of Human Subjects Research Protections at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center. Its methods have been described in detail elsewhere.1 Briefly, we mailed a paper survey to 3872 physicians in the United States, whose names were randomly selected from the American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile database in summer 2012. The survey, entitled “Physicians, Health Care Costs, and Society” (Online Appendix A), addressed topics related to these factors and was administered through US mail in three waves, including a cash incentive in the first mailing.

Survey measures designed to capture self-reported rationing behavior, adapted from a previous survey3 asking respondents to rate the frequency (never, less than monthly, monthly, weekly, daily, or not applicable) with which they “personally refrained, because of cost to the health care system, from using” 10 listed interventions—laboratory tests, routine radiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), screening tests, referral to a specialist, referral to an intensive care unit, prescription drugs, referral for surgery, referral for dialysis, and hospital admission—even when that intervention would have been the best intervention for the patient. This item was intentionally worded to convey the concept of clinician-mediated rationing without using the term “rationing,” in order to minimize any potential social desirability influence on responses.

To empirically test for social desirability around the term “ration,” we embedded a randomized experiment of three versions of a question item in another section of the survey about physician responsibility for containing costs. We randomly assigned each of the 3897 participants to receive an otherwise identical survey containing one of these three wording versions in one item (Fig. 1): “It is my responsibility to exercise wise financial resource stewardship in my daily care of patients”; “It is my responsibility to promote cost consciousness in my daily care of patients”; “It is my responsibility to ration in my daily care of patients.” All versions had the same response options (Strongly agree, Moderately agree, Moderately disagree, Strongly disagree) and appeared in the same place in the order of items within the survey.

Independent Measures

Independent variables included physician demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, race/ethnicity, region of practice, specialty category, political self-characterization, practice setting, and compensation structure). Physician attitudes were appraised through three attitudinal items related to the appropriateness of physician roles in resource allocation (“I should sometimes deny beneficial but costly services to certain patients because resources should go to other patients that need them more”; “Cost to society is important in my decisions to use or not to use an intervention”; and “Physicians should adhere to clinical guidelines that discourage the use of interventions that have a small proven advantage over standard interventions but cost much more”), as reported previously by Hurst et al.3 The primary dependent variable was responding “yes” to any of the several self-reported rationing behaviors listed above.

Data Management and Analysis

Survey responses were double-entered and imported into SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). We used bivariate tests of association (Pearson χ 2 test), as well as multivariate logistic regression, to examine the association between each independent variable and self-reported rationing behavior and to analyze differences in wording that may suggest social desirability bias. We subsequently grouped specialties into the categories of primary care, surgery, procedural specialty, nonprocedural specialty, and nonclinical specialty/other. To capture self-reported rationing behavior in one variable, we subsequently dichotomized responses into one of two groups: “never” for those who reported never refraining from using any of the 10 interventions because of concern about costs (including those who selected “not applicable” or who skipped the question), and “ever” for those who reported refraining from using at least one of the interventions at any frequency (less than monthly, monthly, weekly, or daily). For adjusted associations between physician demographic characteristics and our dependent variable of interest, we created a multivariate logistic regression model containing all listed physician and practice characteristics (Model 1). Then, in a separate model, we added the three attitudinal variables together (Model 2) in which physician and practice characteristics were included as adjusting covariates. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9. Values of p < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Among the 2541 survey respondents (response rate, 65.6 %), the mean age was 51.0 years, with men constituting 69.9 %, and self-reported race including 77.6 % white, 14.7 % Asian American, 3.2 % black or African American, and 4.6 % “other” (23 not reported). Respondents and non-respondents were similar with respect to sex, specialty, practice setting, and region. The mean age was slightly higher among respondents than non-respondents (51 vs. 50 years; Online Appendix B). A majority (64.5 %) practiced in group or health maintenance organization settings, followed by 19.1 % in small or solo practices, 13.2 % working for city, state, or federal governments, and 2.3 % in medical school settings. Practice types by compensation model were billing only (40.9 %), salary plus bonus (34.8 %), salary only (18.3 %), and other compensation models (6.0 %). Our physician sampling strategy did not weight for payer mix. Characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

For the wording experiment, response rates did not differ significantly by experimental arm. Overall, 1299 received the “wise financial stewardship” version, with 848 responding (RR = 65 %); 1298 received the “cost-conscious” version, with 861 responding (RR = 66 %); and 1300 received the “rationing” version, with 847 responding (RR = 65 %; p = 0.81). Respondents in all three arms of the wording experiment were similar with respect to sex, age, region, specialty, practice setting, compensation model, and self-reported political stance. (For reader convenience, a complete comparison of characteristics across groups receiving different versions of the wording is presented in Online Appendix C).

With regard to political characterization, 38.7 % of respondents considered themselves “very conservative” (10.2 %) or “somewhat conservative” (28.5 %) vs. 29.7 % as “somewhat liberal/progressive” (19.8 %) or “very liberal/progressive” (9.9 %); 29.0 % considered themselves “independent/moderate.” Table 1 summarizes the distribution of responses for attitudinal statements that solicited agreement or disagreement with rationing, as previously reported.1

Self-Reported Rationing Behavior

Overall, 53.1 % of physician respondents reported that, because of the cost to the health care system, they had personally refrained from using at least one of the listed specific areas of clinical services within the prior 6 months (Table 2). The clinical services rationed most frequently were prescription drugs (48.3 %) and MRI (44.5 %). Other services were rationed considerably less often (among physicians for whom the service was available), including referral to an intensive care unit (10.9 %), referral for surgery (20.2 %), and hospital admission (18.8 %). The frequency of rationing varied considerably, but most physicians reported performing rationing less than monthly. About one-third of physicians reported rationing prescription drugs and one-fourth rationing MRIs at least monthly. In every clinical category, a small percentage of respondents (usually < %5) reported daily rationing behavior, with prescription drugs the most likely to be rationed (13.5 %).

Characteristics and Attitudes Associated With Rationing Behavior

Bivariate tests of associations (reported as unadjusted odds ratio [OR]) followed by multivariate logistic regression models (reported as adjusted OR) showed that age, sex, region of practice, and practice compensation type were not associated with reporting of ever rationing (Table 3). However, specialty and practice setting and political persuasion were significantly associated with ever having rationing behavior. Surgical and procedural specialists were distinctly less likely to report rationing (OR, 0.8 unadjusted and 0.8 adjusted for surgeons vs. 0.5 unadjusted and 0.4 adjusted for procedural specialists, p < 0.01 for all) compared to primary care (reference group) or nonprocedural specialties (very similar to primary care). When comparing with physicians who reported less rationing from a small or solo practice setting, we found the following unadjusted ORs: group or health maintenance organization setting, 0.8; city, state, or federal setting, 0.7; and medical school setting, 0.4 (p < 0.05 for all). After adjustment, the difference in rationing for the medical school setting remained significant (p < 0.01). Likewise, physicians who characterized their political stance as very or somewhat liberal or progressive were significantly less likely to report rationing behavior (OR, 0.7 unadjusted and 0.8 adjusted; p < .01) than those who reported their political stance as very or somewhat conservative.

In general, in both unadjusted and adjusted analyses, the odds of self-reported rationing behavior among physicians who viewed the permissibility of rationing more favorably (i.e., moderately disagree, moderately agree, or strongly agree) were 1.5 to 1.6 times as high as those who strongly disagreed with the permissibility of rationing.

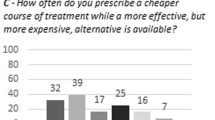

Perceived Responsibility Differences Associated with Varying Social Desirability Wording

Respondents reported varying degrees of agreement/disagreement depending upon the question version they received. Eighty-eight percent of physicians agreed (36 % strongly and 52 % somewhat) with the “wise-stewardship” statement, and 81 % agreed (26 % strongly and 54 % somewhat) with the “cost-conscious” statement, while just 22 % agreed (5 % strongly and 17 % somewhat) with the statement containing “rationing” language (Fig. 2). The overall chi-square test comparing response distributions among the three framing versions was statistically significant (X 2 = 1025.5; p < 0.0001), as were all between-group differences (Group 1 vs. Group 2: p = 0.0003; Group 1 vs. Group 3: p < 0.0001; Group 2 vs. Group 3: p < 0.0001).

Distribution of responses to three randomized versions of wording about physicians’ responsibility for containing health care costs. Note: Differences between groups and overall were all statistically significant (Group 1 vs. Group 2: p = 0.0003; Group 1 vs. Group 3: p < 0.0001; Group 2 vs. Group 3: p < 0.0001; Group 1 vs. Group 2 vs. Group 3: p < 0.0001).

DISCUSSION

Of the US physicians we surveyed, 53.1 % reported having rationed health care resources at least once within the past 6 months. Specialty, practice setting, and political leaning were all associated with self-reported rationing behavior. Physicians who performed procedures were less likely to report rationing behavior. The reasons for this association, however, are unclear. Specialists further downstream in care may have less ability, incentive, or need to ration. Somewhat surprisingly, physicians in small or solo practice settings were more likely to report rationing than those in group or health maintenance organizations or in a governmental context—settings that tend to be associated with more cost-consciousness. Physicians in medical school settings were least likely to report rationing. Our experimental findings lend empirical support for our approach of using a behavioral definition that avoids using the term “ration.”

We found similarities between our results and those by Hurst et al.,3 who assessed rationing behavior among European physicians, and on which some of the structured questions in this survey were based. In the Hurst et al. study, 56.3 % of respondents reported rationing within the past 6 months, compared with 53.1 % of our US respondents. Both the European and US physicians reported MRI scans as among the most frequently rationed services (European physicians, 40.9 %; US physicians, 44.5 %) and that intensive care unit treatment was among the least frequently rationed (European physicians, 13.7 %; US physicians, 10.9 %).3 – 5

There were significant differences in the percentage of physicians reporting rationing behavior in three general categories: (1) MRI and prescription drugs were greatest (40–50 % range); (2) laboratory tests, routine x-rays, screening tests, and specialist and surgical referrals were withheld at an intermediate rate (20–40 % range); and (3) referral to an ICU, referral for dialysis, and hospital admission were withheld the least (8–20+ % of physicians reported rationing). MRI is a high-cost item in outpatient practice and is targeted for prior authorization. Prescription drugs are often considered a separate reimbursement category and may be subject to specific active management by pharmacy benefit managers [PBMs]. On the other end of the spectrum, ICU, dialysis, and hospital admissions all represent more intensive life-or-death services, and routine withholding of these would be a more contentious matter. Whether the possible explanations raised by Hurst regarding European physicians apply to US physicians cannot be answered by these data.

Significant differences were demonstrated for all three questions indirectly asking about attitudes toward physician roles in resource allocation including rationing. One group stands out as statistically distinct: those who strongly disagreed with rationing. In the first question—“I should sometimes deny beneficial but costly services to certain patients…”—which is more individual patient-oriented, 48 % of respondents strongly disagreed, while in the latter two questions, both of which were more theoretically framed as “costs to society” and “adherence to clinical guidelines,” 39 % of respondents were in the group who strongly disagreed in each case. How we conceptualized these attitudinal variables might have influenced the associations we found.

One explanation for differences in rationing behavior among physicians in solo practice might be the rationing by proxy phenomenon. This term describes the situation in which physicians become rationing agents for insurance companies because of the paperwork burden and the excessive prior authorizations or out-of-pocket costs required by payers and pharmacy benefit managers. Solo practitioners who reported greater rationing behavior may have fewer resources to deal with the paperwork and other barriers; it may be easier not to make the effort in the first place when they know that their efforts will likely be in vain or will not be compensated. This response, in turn, could relate to feelings of powerlessness associated with our earlier-reported findings that, overall, physicians rated patients, health systems, and malpractice attorneys as more responsible for addressing healthcare costs than they were.1 Furthermore, although public discourse surrounding rationing often revolves around intensive care unit beds and expensive chemotherapy, these data on the common everyday decisions made by physicians may be as relevant or more relevant to the rationing debate.6 – 8

This study highlights the challenging nature of being a physician in the United States with regard to resource utilization. Everyday clinical decisions involve complex issues, often requiring a series of subtle judgments by an individual physician for each patient (and the patient’s family), which collectively add up to tremendous costs or cost savings. The AMA Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs9 has stated, “Making cost-conscious decisions is not far removed from the professional judgments physicians already make. Physicians routinely decide whether interventions with small benefits are worthwhile,” whether ordering a laboratory stat or a routine test, choosing a brand antibiotic over a generic one, or determining how often to repeat a laboratory test. These decisions are faced several times per patient encounter within the context of larger decisions about inpatient vs. outpatient treatment, medical vs. surgical options, and resource-intensive therapies such as dialysis. The collective outcome of these decisions can mean the difference between high-cost and low-cost health care. One explanation of the discordance between opinion and behavior is the possibility of implicit, subconscious factors influencing clinical decision-making. We recognize that a variety of circumstances may cause physicians to choose a less costly service, such as the desire to reduce patient out-of-pocket expense, not all of which would fall under a narrow definition of rationing. Even with a conservative definition of what constitutes “bedside rationing,” however, we found that a significant number of US physicians reported such behavior. A broad range of behaviors that may or may not constitute bedside rationing were not captured, and these data do not provide reasons that physicians might choose to ration. At a minimum, we can say that there is a complex relationship between physicians’ attitudes toward rationing and their self-reported behaviors related to rationing. We can only speculate on the extent of complexity that future qualitative research could unpack.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to focus on rationing behaviors rather than solely on attitudes regarding rationing among US physicians. The survey avoided the term “rationing” in order to assess self-reported behavior of resource allocation. Findings like these may prompt more honest and sensible professional discourse on this important but controversial topic. Although we avoided the term “rationing” in the survey, the stigma surrounding the word in the United States may have led to underreporting of actual behavior by study participants.

This study has several limitations. Estimates of specialty differences in rationing behavior should be treated with caution, because the AMA Physician Masterfile database relies on self-reported specialty data. Moreover, studying self-reported behavior does not directly address the motivations and intentions behind the behavioral choices described herein. Similarities or differences between these data and those recorded in Europe several years ago, including potential sampling differences, make it difficult to draw direct and specific comparisons. Greater granularity of information regarding the specific practice and patient population characteristics of our respondents would help to further explain the behavior. Unfortunately, such data were not available. We also acknowledge that non-response bias could be a factor in our study.10 , 11 The main contribution of this study is that it goes beyond physician-reported attitudes, to physician self-reported behavior that rationing does occur. However, with respect to self-reported rationing behavior, even if all of the non-responding physicians had reported “never” rationing, that would still mean that about 35 % of US physicians (1348/3872) reported rationing behavior. Future research could examine the disconnect between physician opinion and behavior when it comes to rationing.

We acknowledge the contentious nature of the appropriateness of physician bedside rationing. Some may not agree with the behavioral definition used in this study. US physicians report frequent rationing behavior, and there are differences in self-reported rationing based on a number of factors. Why such differences exist and the impact they have on the practice of medicine and use of resources could be explored in future research. What constitutes “justified restraint” in US health care from the perspective of the ethics of clinical medicine has been addressed by major professional societies in recent years.9 US physicians should be able to safely and openly discuss the ethics of rationing.

Abbreviations

- AMA:

-

American Medical Association

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

References

Tilburt JC, Wynia MK, Sheeler RD, et al. Views of US physicians about controlling health care costs. JAMA. 2013;310(4):380–388.

Ginsburg ME, Kravitz RL, Sandberg WA. A survey of physician attitudes and practices concerning cost-effectiveness in patient care. West J Med. 2000;173(6):390–394.

Hurst SA, Slowther AM, Forde R, et al. Prevalence and determinants of physician bedside rationing: data from Europe. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(11):1138–1143.

Hurst SA, Reiter-Theil S, Slowther AM, Pegoraro R, Forde R, Danis M. Should ethics consultants help clinicians face scarcity in their practice? J Med Ethics. 2008;34(4):241–246.

Hurst S, Forde R, Slowther A, Danis M. The interaction of bedside rationing and the fairness of health care systems: Physicians’ views. In: Danis M, Fleck L, Hurst S, Forde R, Slowther A, eds. Fair Resource Allocation And Rationing at the Bedside. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015:29–39.

Baicker K, Chandra A. Medicare spending, the physician workforce, and beneficiaries’ quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004;Suppl Web Exclusives:W4-184-197.

Fischer MA, Avorn J. Economic implications of evidence-based prescribing for hypertension: can better care cost less? JAMA. 2004;291(15):1850–1856.

Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. part 1: the content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(4):273–287.

Report on the Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs. Physician stewardship of health care resources. American Medical Association CEJA Report 1-A-12, 2012.

Cull WL, O’Connor KG, Sharp S, Tang SF. Response rates and response bias for 50 surveys of pediatricians. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(1):213–226.

Cummings SM, Savitz LA, Konrad TR. Reported response rates to mailed physician questionnaires. Health Serv Res. 2001;35(6):1347–1355.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a grant from The Greenwall Foundation, the Mayo Clinic Program in Professionalism and Ethics, and a Research Early Career Development Award from the Mayo Foundation. The authors would like to thank Katherine Humeniuk for her support in fielding of the survey and for providing preliminary analysis of the data. Joel Pacyna contributed importantly to the preparation and formatting of revised manuscripts.

The study sponsor had no role in study design, including the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in writing the report; or in decisions regarding submission of the manuscript for publication. Except for funding as described above, the researchers were entirely independent of the funders of this study.

Author Contributions

Planning: R.D.S., M.D., S.A.H., S.D.G., B.T., and J.C.T. Conduct: K.M.H. and J.C.T. Reporting: T.M. R.D.S., M.D., S.A.H., S.D.G., K.M.H., B.T., and J.C.T.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Sheeler, R.D., Mundell, T., Hurst, S.A. et al. Self-Reported Rationing Behavior Among US Physicians: A National Survey. J GEN INTERN MED 31, 1444–1451 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3756-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3756-5