ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

More women are using Veterans’ Health Administration (VHA) Emergency Departments (EDs), yet VHA ED capacities to meet the needs of women are unknown.

OBJECTIVE

We assessed VHA ED resources and processes for conditions specific to, or more common in, women Veterans.

DESIGN/SUBJECTS

Cross-sectional questionnaire of the census of VHA ED directors

MAIN MEASURES

Resources and processes in place for gynecologic, obstetric, sexual assault and mental health care, as well as patient privacy features, stratified by ED characteristics.

KEY RESULTS

All 120 VHA EDs completed the questionnaire. Approximately nine out of ten EDs reported having gynecologic examination tables within their EDs, 24/7 access to specula, and Gonorrhea/Chlamydia DNA probes. All EDs reported 24/7 access to pregnancy testing. Fewer than two-fifths of EDs reported having radiologist review of pelvic ultrasound images available 24/7; one-third reported having emergent consultations from gynecologists available 24/7. Written transfer policies specific to gynecologic and obstetric emergencies were reported as available in fewer than half of EDs. Most EDs reported having emergency contraception 24/7; however, only approximately half reported having Rho(D) Immunoglobulin available 24/7. Templated triage notes and standing orders relevant to gynecologic conditions were reported as uncommon. Consistent with VHA policy, most EDs reported obtaining care for victims of sexual assault by transferring them to another institution. Most EDs reported having some access to private medical and mental health rooms. Resources and processes were found to be more available in EDs with more encounters by women, more ED staffed beds, and that were located in more complex facilities in metropolitan areas.

CONCLUSIONS

Although most VHA EDs have resources and processes needed for delivering emergency care to women Veterans, some gaps exist. Studies in non-VA EDs are required for comparison. Creative solutions are needed to ensure that women presenting to VHA EDs receive efficient, timely, and consistently high-quality care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

The number of women Veterans using Veterans’ Health Administration (VHA) services has doubled over the past decade and is expected to continue growing. Concordantly, the number of women using VHA emergency departments (EDs) has also increased. In Fiscal Year (FY) 2010, women Veterans made nearly 102,000 VHA ED visits, which is 9 % of all visits and a 3 % increase over the prior year.1

Women Veterans may have different emergency care needs, and therefore require different resources and processes of care. Nearly 40 % of women using VHA services are aged 45 or less and therefore may present with gynecologic or obstetric emergencies.2 Women VHA users also have higher rates of diagnosed mental illness compared to male VHA users, and may have a particular need for gender-sensitive and gender-appropriate mental health services in the context of their ED care.2 In addition, women are also more likely than men to be victims of sexual assault and present for medical attention after being assaulted.3 Further, if a woman sustained military-related sexual assault, as nearly one in four women who use VHA services do,4 she may be especially sensitive to the need for physical privacy.

Although their numbers are growing, women are still a minority of VHA ED patients, and therefore women-specific ED services may be less available or more difficult to coordinate. Assessments of VHA capacity to deliver emergency care to women have been limited to a single study, conducted over 10 years ago, which focused solely on ED availability of women’s care specialists (e.g., gynecology). 5 Therefore, as a foundation for VHA planning and potential quality improvement efforts, a comprehensive assessment of the resources and processes used by VHA EDs was needed. The VHA Offices of Women’s Health Services and Emergency Services cosponsored the conduct of a national inventory of emergency services for women (ESW). This paper reports on the ESW findings on resources and processes in place in VHA EDs for gynecologic, obstetric, sexual assault and mental health care, as well as privacy, and assesses for their differences by facility and ED characteristics. We hypothesized that smaller EDs and those with fewer encounters by women would have less access to female-specific equipment, supplies and medications. We further hypothesized that EDs in less complex facilities and non-metropolitan communities would have less access to gynecology consultations, female-specific laboratory and radiologic services, and be more likely to have written transfer policies in place.

METHODS

Questionnaire Development

In an iterative process, with a panel of experts in emergency medicine, gynecology, mental health, and health services research, we developed a list of VHA resources and processes that could potentially affect the quality of care delivered to women presenting to VHA EDs. Of these, we identified those about which ED directors would be likely to have first-hand knowledge. Table 1 shows the final list of topics and measures. In consultation with a survey expert, two investigators (KMC, LCZ) drafted preliminary questions for each topic. We re-engaged our panel of experts to review the candidate questions and revised them based on their comments. The draft instrument was then pre-tested with three emergency medicine boarded physicians who were not part of our panel and are, or have been, VHA ED directors. With this pre-testing, we assessed each question for its content appropriateness and feasibility, as well as clarity of question wording and response categories, revising as needed. The final questionnaire is available online (Appendix).

Questionnaire Administration

The questionnaire was administered as a mandated activity by the VHA Office of the Deputy Under Secretary for Health for Operations and Management (DUSHOM). Therefore, the project was determined to be a nonresearch operations activity by the Institutional Review Board of the VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System. On May 24th, 2011, DUSHOM sent the questionnaire in an Adobe Acrobat® Portable Document Format (PDF) to all VHA Veterans’ Integrated Service Networks (VISNs), with instructions to have all ED directors in their regions complete it by June 13th, 2011. The VISNs forwarded this e-mail to facility directors, with instructions to forward it to ED directors. In addition, the lead investigator (LI) (KMC) sent an e-mail to the 120 ED directors, providing them with the PDF version of the questionnaire. The ED director was instructed to fill in the PDF questionnaire, have it reviewed by their facility’s chief of staff (i.e., medical director), and then enter responses into an Allegiance Engage® 7.0 web-based tool, accessed by a link provided in the e-mails. The LI sent ED Directors two reminder e-mails. On the due date, the LI sent ED Directors with incomplete questionnaires a third reminder e-mail and informed appropriate VISN staff, who also contacted facility and ED directors. All surveys were completed by June 30th, 2011.

Data Analysis

We analyzed responses using STATA 11.0.® In addition to descriptive statistics, we stratified responses by number of ED encounters by women, ED size, facility complexity, and community characteristics. We did not perform multivariate analysis with these characteristics due to their high inter-correlation. We obtained number of Fiscal Year 2010 encounters by women for each ED from VHA’s National Patient Care Database.6 As a proxy for ED size, we used number of staffed ED beds obtained from VHA’s 2010 Survey of Emergency Departments.7 VHA classifies facilities into five complexity levels (1a,1b,1c, 2, and 3), with level 1 being the most complex, and level 3 the least, based on the patient population (e.g., number and risk characteristics); clinical services complexity (e.g., level of intensive care); and education and research activities (e.g., resident slots and research funding).8 We obtained these designations from VHA’s Office of Productivity, Efficiency, and Staffing. We combined 1a, 1b, and 1c facilities for our analyses. Community characteristics (i.e., located in a large metropolitan, small metropolitan or non-metropolitan area) were obtained from the 2009–2010 Area Resource File.9

RESULTS

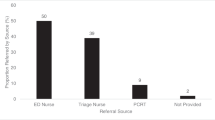

We received completed questionnaires from 100 % of EDs. Their characteristics are shown in Table 2. The ED director either personally completed, or designated another person (e.g., ED Nurse Manager, Women Veterans Program Manager) to complete it and then concurred with or edited responses.

Resources and Processes for Gynecologic and Obstetric Care

Table 3 shows resources and processes for gynecologic and obstetric care reported as available at all times (24/7). Most, but not all, VHA EDs reported having the equipment and supplies to care for patients with gynecologic and obstetric complaints. Approximately nine out of ten EDs reported having a gynecologic examination table and nearly all reported either stocking specula or having them available from a centralized supply source 24/7. Approximately nine out of ten EDs also have large/extra-large and small/extra-small specula available 24/7. Most EDs reported having DNA probes for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea; however, DNA probes for detecting vaginal yeast, trichomonas, and bacterial vaginosis were reported as less commonly available.

Laboratory testing for gynecologic and obstetric conditions were also reported as available in most, but not all, EDs. Pregnancy testing was available at all times in all EDs, either with urine or serum testing. However, point-of-care testing for pregnancy was reported as uncommon, with fewer than one out of ten VHA EDs having it available. Approximately nine out of ten EDs reported having serum quantitative Beta Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (β-HCG) and Rh-factor screening available 24/7.

Radiologic testing and specialty consultations, however, were reported as much less available. Fewer than half of VHA EDs have radiologic testing capabilities for gynecologic emergencies 24/7. Although 86 EDs (72 %) have pelvic ultrasound available, with radiologist review, at least some of the time, fewer than two-fifths have this available 24/7. An additional 3 % of EDs reported having ultrasound available 24/7 without radiologist review. Two-thirds of the EDs reported having emergent consultations from gynecologists available at least some of the time; however, just over one-third reported having them available 24/7. Fewer than half of EDs reported having obstetric consultation available with one-fifth having them 24/7. In comparison, urology, cardiology and neurosurgery consultations were reported as available in 98 %, 95 % and 78 % of EDs, respectively.

Written transfer policies specific to gynecologic and obstetric emergencies were reported as available in fewer than half of EDs. Written transfer policies specific to gynecologic emergencies were less available in EDs without 24/7 gynecology consultations. Of the 78 EDs without 24/7 gynecology consultation, 49 (63 %) of the 78 EDs reported not having them in place (not shown in table).

Regarding medications, most VHA EDs reported having the ability to provide emergency contraception 24/7. Only approximately half reported having Rho(D) Immunoglobulin available 24/7.

Resources and processes to support nursing care for gynecologic conditions were not commonly available. One-third of EDs reported having designated spaces for documenting last menstrual period within their nurse triage note templates, and fewer than one in ten have specialized nurse triage note templates for vaginal bleeding or discharge. Two-fifths of EDs reported having standing orders for urine pregnancy testing. In comparison, standing orders for the use of electrocardiogram are used in 88 %, and for finger-stick glucose testing in 75 %, of EDs. Fewer than one in ten EDs reported having standing order sets for vaginal bleeding, while 79 % use them for chest pain and 48 % for signs of stroke.

Resources and Processes for Sexual Assault Care

Most VHA EDs reported having processes in place for transferring victims of acute sexual assault to another institution for evaluation and/or treatment (Table 3). Of the ten EDs that did not, seven reported having a formal arrangement or contract for obtaining consultation from a rape crisis center, a sexual assault nurse examiner (SANE) unit, another organization with expertise in the issues of acute sexual assault, or a formal arrangement for on-site services from at least one practitioner trained in conducting a sexual assault forensic evidentiary examination. Three EDs that reported not transferring victims of acute sexual assault also reported not having any arrangement for sexual assault medical or evidentiary examination expertise. One of these three EDs reported using clinician note templates specific for sexual assault and having a written protocol guiding the collection of evidence.

Among all 120 EDs, 59 % had a mechanism for obtaining urgent mental health follow-up for sexual assault victims in less than 24 h, 18 % between 24 and 47 h, 3 % between 48 and 72 h, 8 % between 72 h and 1 week, and 15 % greater than 1 week or not at all.

Emergency Department Layout

Most, but not all, EDs reported having some access to private medical and mental health rooms. Ninety-five percent of the EDs have at least one private room; however, 13 % reported having only one or two. Of the 106 EDs that have gynecologic examination tables, all but two have at least one private gynecologic examination room. For mental health treatment, 69 % reported having private rooms in their psychiatric treatment area or a separate area for women receiving psychiatric evaluation and treatment.

Comparisons by ED Characteristics

Table 4 shows selected items related to our hypotheses that smaller EDs and those with fewer encounters by women and smaller in physical size would have less access to equipment, supplies and medications for female-specific conditions. Analyses in general, confirmed these hypotheses. However, some of the EDs with more than 2,000 ED encounters by women and more than 15 beds lacked some items needed for caring for women, such as having a gynecologic examination table within the ED and 24/7 access to emergency contraception and Rho(D) immunoglobulin.

Analyses also confirmed our hypotheses that EDs in less complex facilities and non-metropolitan communities had less access to laboratory and radiologic services, as well as gynecologic consultations. They were not more likely to have written transfer policies in place (Table 5).

24/7 available at all times,

DISCUSSION

In summary, our inventory of VHA EDs revealed that most have access to resources and processes needed for delivering emergency care to women Veterans. However, as hypothesized, EDs with lower demand for female-specific services (i.e., fewer encounters by women) and EDs that are smaller and located in less complex facilities in non-metropolitan areas are more likely to lack such resources and processes. We nonetheless also identified some higher-demand, larger EDs, and EDs in complex metropolitan VAs, with potentially important gaps.

Overall, we found that many VHA EDs have gaps when compared to the resources recommended by a 2007 American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) policy statement.10 With respect to obstetrics and gynecology, ACEP recommends that all EDs should have gynecologic examination tables; specula of various sizes; emergency obstetric instruments and supplies; sexual assault evidence kits (as appropriate); qualitative and quantitative pregnancy testing; blood cross-matching capabilities (which includes Rh Factor); Chlamydia testing (DNA probe versus culture not specified); Rho(D) immunoglobulin; oral contraceptives; and “emergency ultrasound services for the diagnosis of obstetric/gynecologic… conditions.” ACEP also asserts that “The ED should be designed to protect, to the maximum extent reasonably possible … the right of the patient to visual and auditory privacy.” Further, the hospital “must provide to the ED a list of appropriate ‘on-call’ specialists who are required to respond to assist in the care of emergency patients within reasonable established time limits.” Currently, to our knowledge, no other national ED inventories have been conducted against which we could compare our VHA results. This gap in knowledge of how U.S. emergency care is organized and delivered warrants further study. More research related to the costs and feasibility of achieving the ACEP standards with varying facility and community characteristics, as well as the quality and outcomes of care they afford, is also needed.

Absence of ED equipment and supplies for emergency gynecologic care may potentially result in care delays and sub-optimal outcomes. Having gynecologic examination supplies stocked in the ED decreases the likelihood of delays secondary to waiting for supplies. Where supplies and expertise are not available, women may need to be transferred to neighboring facilities to receive needed care. EDs without gynecologic examination tables may use those in nearby primary care or women’s clinics, but this may mean that the patient leaves the monitored ED area to complete the examination and access to these areas may be more difficult, or not available, after hours. Pelvic ultrasound is also a key component in evaluating a pregnant woman presenting with abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding.11 Therefore, any ED without pelvic ultrasound access should transfer to other facilities all pregnant women Veterans with abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding. Similarly, any woman with a suspected gynecologic emergency presenting to an ED without available specialty consultations may need to be transferred to another facility with this capability. The time it takes to transfer these women, and arrange for the transfer where expedited acceptance agreements are not in place, will extend the time to treatment of time-sensitive conditions. While national VA policy references the need to effectively treat women Veterans under emergent conditions, 12–14 more specific guidelines may be needed so that consistent resources and processes are available across VHA EDs, and/or, if these resources or processes are not available, expedited arrangements are in place to provide women Veterans with the timely care they need.

Although all VHAs contract with other facilities for obstetric care, women may present to VHA EDs with pregnancy-related emergencies. Some of these emergencies, such as miscarriages and ectopic pregnancies, may occur without the patient having previous knowledge of the pregnancy. The ED needs to have a mechanism for women who have Rh-negative blood type to receive Rh Immunoglobulin within 48 h. In the event that Rh Immunoglobulin is not administered when indicated, a woman’s future pregnancies may be negatively affected. Although uncommon, women may present to VHA EDs later in pregnancy as well, and VHA EDs need to be prepared for these situations, at least with policies and procedures for rapid transfer to facilities that do deliver obstetric care.

Almost all VHA EDs report adherence with VHA’s directive on caring for acute sexual assault victims, stating that all EDs must “have plans in place to appropriately manage the medical and psychological assessment, treatment, and collection of evidence from male and female Veterans who are victims of alleged acute sexual assault.” 14 However, 41 % of VHA EDs reported not having the capacity to arrange for mental health follow-up within 24 h, which is also part of this policy. The importance of urgent follow-up mental health care for sexual assault victims has been well-documented.15

Our findings must be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, the data are facility-reported without independent verification of accuracy. If responses reflect social desirability, we posit that gaps may be broader than reported. Second, our measures of ED structure and processes vary with respect to levels of evidence linking them to care quality. For example, although there is evidence about the importance of follow-up for medical and psychiatric care for sexual assault victims,12 we do not know how having a gynecologic examination table within the ED, rather than in a nearby clinic, impacts care quality. Thirdly, we were unable to find a similar inventory of resources and processes for non-VA EDs, and therefore we do not know how our findings compare to community EDs. An investigation of community ED adherence to ACEP recommendations is needed. Finally, all resources and processes can only impact the care of patients to the extent to which they are actually used and used appropriately. One of the most significant factors impacting the care of women for these conditions is the knowledge and skills of the ED providers, and the gender-sensitivity with which they deliver care, neither of which were captured in our inventory approach. All of these limitations should be addressed in future investigations.

Over the past decade, VHA has devoted considerable effort to improving the care it provides to women Veterans. However, this inventory revealed that gaps remain with respect to resources and processes for their emergency care. Exploration of facilitators and barriers to addressing these gaps, such as logistical considerations, is needed. Despite their growing numbers, women Veterans still represent a relatively small proportion of the overall patient population and therefore providing them with efficient, timely, and consistently high-quality care is an organizational challenge. Future work should seek creative solutions to this challenge to further the goal of VHA achieving standards of gender equity across all services delivered.

REFERENCES

Frayne SM, Phibbs C, Friedman SA, et al. Sourcebook: Women Veterans in the Veterans Health Administration. Volume 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Utilization of VHA Care. Washington DC: Department of Veterans Affairs; 2010.

Haskell SG, Gordon KS, Mattocks K, et al. Gender differences in rates of depression, PTSD, pain, obesity, and military sexual trauma among Connecticut War Veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan. J Women’s Health (Larchmt). 2010;19(2):267–271.

Tjaden P, Thoennes N. Prevalence, Incidence and Consequences of Violence Against Women Findings From the National Violence Against Women Survey. Washington, DC: Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice; 1998. NCJ 172837.

Skinner KM, Kressin N, Frayne S, et al. The prevalence of military sexual assault among female Veterans’ Administration outpatients. J Interpers Viol. 2000;15(3):291–310.

Washington DL, Yano EM, Goldzweig C, Simon B. VA emergency health care for women: –critical or stable? Womens Health Issues. 2006;16(3):133–138.

VA National Patient Care Database, Outpatient Cube, http://www.virec.research.va.gov/NPCD/Overview.htm, accessed Dec 20th, 2012.

VA Patient Care Services, Office of Emergency Medicine, VHA’s Survey of Emergency Departments, Washington, D.C.; 2010.

VHA’s Office of Productivity, Efficiency, and Staffing, Fiscal Year 2008 Facility Complexity Levels List. Available at: http://opes.vssc.med.va.gov/FacilityComplexityLevels/Pages/default.aspx, accessed Dec 20th, 2012.

U.S. HealthResources and Services Administration. 2009–2010 Area Resource File. Bureau of Healthcare Professions, Rockville, MD.

American College of Emergency Physicians. Emergency Department Planning and Resource Guidelines. 2007. http://www.acep.org/policystatements/, accessed Nov 12th, 2012.

Lambert MJ, Villa M. Gynecologic ultrasound in emergency medicine. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2004;22(3):683–696.

VHA Handbook 1101.05, VHA’s Emergency Medicine Handbook. http://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2231, accessed Nov 22nd, 2012

VHA Handbook 1330.01, Health Care Services for Women Veterans. http://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2246, accessed Nov 22nd, 2012

VHA Directive 2010–014, Assessment and Management of Veterans Who Have Been Victims of Alleged Acute Sexual Assault. http://www.va.gov/vhapublications/ViewPublication.asp?pub_ID=2177, accessed Nov 22nd, 2012

Holmes MM, Resnick HS, Frampton D. Follow-up of sexual assault victims. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179(2):336–342.

Acknowledgements

Contributors

This work was performed in collaboration with VA’s Office of Specialty Care Services, Office of Emergency Medicine (Dr. Gary Tyndall, Director). We are also grateful for assistance of the VA ESW Workgroup members Amanda Johnson, MD; Lisa Nocera, MD; and Amy Sadler, MPH.

Funders

This project was funded by the VHA Office of Women’s Health Services (Project # XVA 65–027), with in-kind support from the VA Women’s Health Research Consortium (Project # SDR 10–012). Dr. Yano’s effort was covered by a VA HSR&D Research Career Scientist Award (RCS #05-195).

Prior Presentations

This work was presented at the 2012 Society of General Internal Medicine Meeting; the 2012 Academy Health Gender and Health Interest Group Meeting; the 2012 Academy Health Annual Research Meeting and the 2012 VA Health Services Research and Development Meeting.

Conflict of Interest

All authors are employees of the Veterans’ Health Administration. The authors have no other conflicts of interest with this work.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(PDF 1078 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0 ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Cordasco, K.M., Zephyrin, L.C., Kessler, C.S. et al. An Inventory of VHA Emergency Departments’ Resources and Processes for Caring for Women. J GEN INTERN MED 28 (Suppl 2), 583–590 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2327-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-012-2327-7