ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

At-risk drinking, excessive or potentially harmful alcohol use in combination with select comorbidities or medication use, affects about 10% of elderly adults and is associated with higher mortality. Yet, our knowledge is incomplete regarding the prevalence of different categories of at-risk drinking and their associations with patient demographics.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the prevalence and correlates of different categories of at-risk drinking among older adults.

DESIGN

Cross-sectional analysis of survey data.

SUBJECTS

Current drinkers ages 60 and older accessing primary care clinics around Santa Barbara, California (n = 3,308).

MEASUREMENTS

At-risk drinkers were identified using the Comorbidity Alcohol Risk Evaluation Tool (CARET). At-risk alcohol use was categorized as alcohol use in the setting of 1) high-risk comorbidities or 2) high-risk medication use, and 3) excessive alcohol use alone. Adjusted associations of participant characteristics with at-risk drinking in each of the three at-risk categories and with at-risk drinking of any kind were estimated using logistic regression.

RESULTS

Over one-third of our sample (34.7%) was at risk. Among at-risk individuals, 61.9% had alcohol use in the context of high-risk comorbidities, 61.0% had high-risk medication use, and 64.3% had high-risk alcohol behaviors. The adjusted odds of at-risk drinking of any kind were decreased and significant for women (odds ratio, OR = 0.41; 95% confidence interval: 0.35-0.48; p-value < 0.001), adults over age 80 (OR = 0.55; CI: 0.43-0.72; p < 0.001 vs. ages 60-64), Asians (OR = 0.40; CI: 0.20-0.80; p = 0.01 vs. Caucasians) and individuals with higher education levels. Similar associations were observed in all three categories of at-risk drinking.

CONCLUSIONS

High-risk alcohol use was common among older adults in this large sample of primary care patients, and male Caucasians, those ages 60-64, and those with lower levels of education were most likely to have high-risk alcohol use of any type. Our findings could help physicians identify older patients at increased risk for problems from alcohol consumption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

INTRODUCTION

Approximately half of men and more than one-third of women in the U.S. over age 60 are current drinkers.1,2 While moderate amounts of alcohol consumption generally confer health benefits, older adults may experience negative health consequences from even moderate quantities of alcohol consumption (e.g., 1-2 drinks on most days).3–9 This level of alcohol use can be harmful for older adults due to physiological changes that increase the effects of a given dose of alcohol, as well as increased age-associated morbidity and medication use.9–16 Medication interactions with alcohol can occur in older adults due to changes in absorption, distribution, and metabolism of alcohol. Adverse interactions can occur between alcohol and other drugs, such as disulfiram-like interactions with some beta-lactam cephalosporins and nitrates, and sedation and impaired coordination with benzodiazepines and sedating antihistamines. Alcohol can also exacerbate or reduce a medicine’s therapeutic effects (e.g., warfarin), and interfere with the effectiveness of some medications to treat conditions like hypertension, gastroesophageal reflux, insomnia, and depression.13 Drinking is known to cause or worsen conditions such as liver disease, gastritis and other gastrointestinal conditions, depression, gout, insomnia, hypertension, as well as many varieties of cancer, and can result in accidents and injuries.6,17

We previously defined at-risk drinking to be alcohol use that is excessive or potentially harmful in combination with select comorbidities or medications.8,9,13,15,18–20

Based on national data, the prevalence of this form of “at-risk drinking” is estimated to be 10% among all elderly adults and 26% among older adults who are current drinkers.8 These data have demonstrated the association of at-risk drinking with increased mortality rates among older men.8 Despite this significant public health burden, our knowledge is incomplete about differences in the prevalence of specific categories of at-risk drinking among older drinkers (i.e., alcohol behaviors, alcohol use combined with select comorbidities or medications), or the demographic characteristics associated with at-risk drinking.

Understanding differences in the prevalence of various categories of at-risk drinking among elderly adults could help physicians to screen, counsel, and provide treatment recommendations for this group. Although there is considerable evidence about the demographic correlates of heavy drinking (e.g., age, gender, income, race/ethnicity) 10,21–23, these correlates may not be the same for at-risk drinkers. For example, older adults may drink less but also use more medications and have more comorbidities that may negatively interact with alcohol. Conversely, increases in risk due to higher alcohol consumption may be offset in demographic subgroups that use fewer medications or have fewer comorbidities. Hence, associations with at-risk drinking could diverge from those with heavy alcohol consumption or alcohol dependence. Furthermore, physicians are less likely to ask older patients about their alcohol use compared to younger patients due to poor understanding of the associations between patient characteristics and at-risk drinking. 24–28 This knowledge gap could decrease the likelihood of clinicians identifying or intervening in cases of alcohol misuse. The two studies that assessed correlates of at-risk drinking among elderly adults found that men, those under 75 years of age, and married people were more likely to be at-risk drinkers. However, these studies did not adjust for demographic covariates that may bias these associations.8,19 Furthermore, the instrument used to identify at-risk drinkers in many of the previous studies has been revised to incorporate new findings in the medical literature relevant to at-risk drinking among older adults.8,9,13,16,20,29,30

In order to fill the gaps in our understanding of the categories of at-risk drinking and the association of demographic characteristics with these categories, we examined data from 3,308 elderly patients, age 60 years and older, of primary care physicians practicing at Santa Barbara, California area clinics.

METHODS

Setting

This study used baseline data from Project SHARE (Senior Health and Alcohol Risk Education), which tested the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of an educational intervention to reduce at-risk drinking in adults age 60 years and older. The study population was drawn from Sansum Clinic, a community-based group practice with seven clinics in the Santa Barbara, California area. The practice has a strong primary care base, with service lines representing all major specialties and sub-specialties appropriate for elder care (e.g., cardiology, diabetes, geriatrics, urology).

Recruitment

Of the 42 primary care physicians approached, 31 agreed to participate in the study (n = 21 male, 10 female, 17 internal medicine, 14 family practice). Clinic information technology personnel identified all adults 60 and older who were current patients of these providers (n = 12,573). Providers initially screened out 2,159 patients who met one or more of the following exclusion criteria: severe cognitive impairment, terminal illness, inability to speak and understand English, or intention to leave the practice within the next year. Subsequently, another 635 participants were taken off the recruitment list because their physician left the study clinic. Of the remaining patients, 9,476 were mailed recruitment letters and 6,919 patients agreed to participate. These patients were screened via telephone to assess whether they were a current drinker (consumed at least one alcoholic drink in the past three months) and to confirm that they met the age criterion and were planning to remain in the community over the next year. In all, 4,217 patients met all inclusion criteria and were mailed a baseline survey. Of the 3,529 returned baseline surveys, 3,308 were complete. Participants were paid $5 for completing the baseline survey. If surveys were not returned within a month, a maximum of two reminder calls were made (the first a month after the survey was sent and the second two weeks later). If study personnel did not receive a survey after the reminder calls, they mailed a second survey with the $5 incentive.

MEASURES

At-Risk Drinking

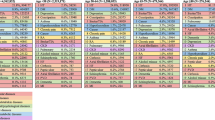

To identify at-risk drinkers, study subjects completed the Comorbidity Alcohol Risk Evaluation Tool, or CARET (Table 1). The CARET, an updated and revised version of the Short Alcohol-Related Problems Survey (ShARPS), has demonstrated face, content, and criterion validity for assessing at-risk drinking among older adults.16,20,29,31 The CARET identifies older adults at risk for harm from their alcohol consumption based on alcohol use behaviors (e.g. quantity, frequency, driving after drinking) or the combination of quantity and frequency of alcohol use with select comorbidities (e.g., gout, hepatitis, nausea), or medications (e.g., antidepressants, sedatives) (Table 1).16,29,30 In addition to overall risk, we examine three distinct categories of at-risk drinking with clinical relevance: alcohol behaviors, alcohol use and select comorbidities, and alcohol use combined with certain medications.

Demographic Variables

Hypothesized correlates of at-risk drinking include age, gender, race/ethnicity, education, marital status, annual household income and home ownership. In previous studies of alcohol consumption by the elderly, greater use was reported by whites, unmarried individuals, and males. 2,8,9,20,21,32,33 However, the adjusted demographic correlates of overall and specific categories of at-risk drinking have not yet been examined. For example, although heavy alcohol consumption declines with age, comorbidities and medication use associated with at-risk drinking increase. Hence the association of at-risk drinking with increasing age may be positive, negative, or equivocal. 8,23 Similarly, financial resources are positively associated with alcohol consumption in the general population, but little is known about their relationship with at-risk drinking among older adults.34–36

DATA ANALYSIS

All analyses were based on 3,308 participants with complete data. Sensitivity analyses using multiple imputations yielded no appreciable changes in the magnitude or strength of associations. All statistical analyses were computed using Stata Version 10.1 (Stata Corp).

Frequency distributions of sample characteristics were calculated, and chi-square statistics were used to compare at-risk and not at-risk older drinkers. Logistic regressions were specified to analyze the adjusted odds of any at-risk drinking and category of at-risk drinking, controlling for gender, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, household income, and home ownership. Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are presented.

RESULTS

Prevalence of At-risk Drinking

Of the 3,308 current drinkers in our sample, 34.7% were at-risk drinkers due to either alcohol behaviors or alcohol use combined with certain comorbidities or medications, and 19.5% fell into multiple risk categories. Among the 1,147 at-risk drinkers, 56.1% fell into at-least two risk categories and 31.0% fell into all three risk categories. Among all current drinkers, similar proportions were at risk due to alcohol behaviors (22.3%), alcohol use with select comorbidities (21.5%), and alcohol use combined with certain medications (21.2%). Among at-risk drinkers, these proportions were 64.3%, 61.9%, and 61.0%, respectively.

Sample Characteristics

The majority of the 3,308 participants used in our regression analyses were under age 75 (65.2%), married (72.0%), college-educated (57.2%), home owners (87.2%), and white (96.3%), although 5.7% were of Latino ethnicity (Table 2). Just over half (51.8%) were male and 59.1% reported household incomes below $80,000 per year.

Unadjusted Correlates of At-risk Drinking

The unadjusted probability of being an at-risk drinker differed by gender with 24.7% of women at-risk compared to 56.0% of men (p < 0.001; Table 3). The probability of being at-risk was generally lower for older age groups than younger ones (p < 0.001). At-risk drinking also differed by marital status (p = 0.002) with married individuals reporting the highest risk (36.8%). Risk also differed by years of education (p = 0.004), and was highest for participants not completing high school (51.4%). Likelihood of being at risk also varied by income (p < 0.001). However, the unadjusted probability of at-risk drinking did not differ significantly by race, ethnicity or home ownership.

Adjusted Associations of Sample Characteristics and At-risk Drinking

Results from the adjusted associations were similar to the unadjusted associations (Table 4). Female participants had half the odds (OR = 0.41; CI: 0.35-0.48) of any at-risk drinking compared to males. Individuals 80 years and older had 0.55 (CI: 0.43-0.72) times the odds of at-risk drinking compared to individuals 60-64 years old. Older adults who did not complete high school had higher odds than those with a graduate school degree (OR = 2.44; CI: 1.45-4.10). Asians in our sample had lower odds of being at-risk drinkers compared to whites (OR = 0.40; CI: 0.20-0.79). Respondents with annual household incomes between $80,00—$100,000 had 1.49 (CI: 1.09-2.05) times the odds of being at-risk compared to those with incomes under $30,000.

Adjusted Associations of Sample Characteristics and Category of At-risk Drinking

After adjusting for other patient characteristics, women in our sample had lower odds of being an at-risk drinker due to alcohol behaviors (OR = 0.28; CI: 0.23-0.34), alcohol use combined with select comorbidities (OR = 0.46; CI: 0.38-0.55), and alcohol use with certain medications (OR = 0.56; CI: 0.46-0.67) (Table 5). Relative to adults ages 60-64, odds of at-risk drinking due to alcohol behaviors were lower for participants ages 70-74 (OR = 0.69; CI: 0.53-0.91), 75-79 (OR = 0.58; CI: 0.43-0.77) and 80 and older (OR = 0.37; CI: 0.27-0.51). Similarly, alcohol use combined with comorbidities was lower for adults ages 70-74 (OR = 0.75; CI: 0.57-0.98), 75-79 (OR = 0.73; CI: 0.54-0.97); and 80 and older (OR = 0.64; CI: 0.48-0.87) compared to adults ages 60-64. However, we found no differences in the adjusted odds of alcohol use combined with medications across age groups.

Compared to older adults with a graduate education, those without a high school degree had more than twice the odds of being at-risk due to alcohol behaviors (OR = 2.48; CI: 1.42-4.35), alcohol use combined with select comorbidities (OR = 2.90; CI: 1.69-4.98), and alcohol use combined with certain medications (OR = 2.13; 1.23-3.68). When compared to older adults with a graduate degree, those with a high school diploma had 1.47 (CI: 1.08-2.01) times the odds of being at risk due to alcohol use combined with certain comorbidities and those with some college education had 1.41(CI: 1.12-1.78) times the odds. Relative to whites, Asians in our sample had less than half the adjusted odds of at-risk drinking due to alcohol behaviors (OR = 0.42; CI: 0.18-0.95) and alcohol use combined with certain medications (OR = 0.20; CI: 0.026-0.65). Finally, across risk categories, we found no effects for Latino ethnicity, marital status, income, or home ownership.

DISCUSSION

In our sample, over one-third of older drinkers were at risk of harm either because of the combined use of alcohol with selected medications and comorbidities or the amount of alcohol consumed and related behaviors. Therefore, at-risk drinking was a considerable health concern for this group. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) defines at-risk drinking in the Clinician’s Guide as consuming fewer than four drinks per day and fewer than 14 drinks per week for healthy men under 65 years of age, and fewer than three drinks per day and fewer than 7 drinks per week for healthy women and healthy men over 65 years of age. According to this definition, 29.0% of our sample would be classified at-risk.38 The CARET’s alcohol quantity/frequency thresholds are higher than the Clinician’s Guide, yet it identifies more older adults at risk due to the inclusion of potentially harmful interactions of medications and comorbidities with amounts of alcohol otherwise considered low risk. Notably, as many older adults were at-risk drinkers due to alcohol consumption in the context of comorbidities (21.5%) or specific medication use (21.2%) as from their alcohol use alone (22.3%). The majority (56.1%) of at-risk drinkers fell into multiple risk categories.

Our results are largely consistent with the past literature examining the unadjusted associations of older adults’ characteristics with harmful drinking behaviors.8,19 However, in contrast to earlier studies based on bivariate associations, we found no evidence that married individuals are at increased risk of harmful drinking after controlling for other participant demographics.8 One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that married participants tend to be male and younger.39 We also find no age associations with risk due to alcohol use in combination with medications. This suggests that, as individuals age, risk reduction resulting from consuming less alcohol may be offset by increased medication use.

Our findings are relevant for physicians wishing to counsel older patients on the risks of alcohol consumption.24 Limited physician time suggests the need to prioritize counseling. Inadequate information about which older patients are at high risk of alcohol-related harm makes it challenging to give advice to patients that could benefit from such counseling. Specifically, we find at-risk drinking among our sample of older patients is positively correlated with being younger, male, and less educated after for controlling other patient demographics. These findings may help physicians identify elderly patients at greatest risk for harm from drinking, making provider interventions more efficient. As an example of how widely risks can vary, consider the following hypothetical patients, both current drinkers who completed college and own their own homes. A 62-year-old married, male, white patient with an annual household income of $90,000 is estimated to have a 57.1% adjusted probability of being an at-risk drinker, compared to an 8.1% adjusted probability for an 85-year-old widowed, female, Asian patient with an income of $35,000.

When interpreting our findings, the following limitations should be considered. Drinking frequency and quantity relied on patient self-report, so it is possible that some patients were misclassified. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that patient self-reported alcohol consumption tends to be reliable and valid.40 Most importantly, compared to the U.S. Census population over 60, our sample was more likely to be white, married, well-educated and high income.41 The greatest difference was in the probability of having a college or graduate degree (57.1% vs. 21.5%).41 The literature generally finds education to be a protective factor against harmful drinking.36,42,43 Given the relatively well-educated sample studied, our at-risk drinking prevalence estimates may understate the number of elderly at risk in less educated populations.36,42–44 With respect to income, our estimates of at-risk drinking prevalence are likely to be overstated if extended to less wealthy populations.44 However, the proportion of our study population reporting at least one drink in the past 90 days (64.1%) seems broadly consistent with the proportion of adults over 60 reporting having a drink in the last 30 days (50.3%) obtained from the 2003 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS).45 Statewide, 5.2% of older adults reported binge drinking in the last 30 days vs. 3.4% of the Project SHARE participants.45 Additionally, the adjusted associations of patient characteristics with at-risk drinking should be more broadly generalizable than the (univariate) descriptive data. Ultimately, however, replication of our findings among a nationally representative sample is needed to ensure generalizability.

In summary, even among our relatively advantaged study patients, as many as one in three who continued to consume alcohol into older adulthood were at risk of harm from drinking. Physicians may be less aware of other alcohol-related risk factors common among the elderly (e.g., interactions with select medications and comorbidities) than the risks associated with heavy drinking. Information suggesting which patients have the highest likelihood of at-risk drinking may assist physicians to better target patients for further screening and early intervention. Potential interventions may include changing (or in the case of non-essential medications, discontinuing) medications to avoid harmful interactions and counseling patients to reduce alcohol consumption. However, more evidence is needed to understand how physicians can effectively intervene once at-risk older drinkers are identified and whether or not these interventions are cost effective.

References

Breslow RA, Faden VB, Smothers B. Alcohol consumption by elderly Americans. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(6):884–92.

Chan KK, Neighbors C, Gilson M, Larimer ME, Alan Marlatt G. Epidemiological trends in drinking by age and gender: providing normative feedback to adults. Addict Behav. 2007;32(5):967–76.

O'Keefe JH, Bybee KA, Lavie CJ. Alcohol and cardiovascular health: a razor sharp double edged sword. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(11):6.

Klatsky AL. Alcohol, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol Res. 2007;55:11.

Russell M, Cooper ML, Frone MR, Welte JW. Alcohol drinking patterns and blood pressure. Am J Public Health. 1991;81(4):452–7.

Standridge JB, Zylstra RG, Adams SM. Alcohol consumption: an overview of benefits and risks. South Med J. 2004;97(7):9.

Blow FC, Barry KL. Older patients with at-risk and problem drinking patterns: new developments in brief interventions. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2000;13(3):115–23.

Moore A, Giuli L, Gould R, et al. Alcohol use, comorbidity, and mortality. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(5):757–62.

Fink A, Hays R, Moore A, Beck J. Alcohol-related problems in older persons. Determinants, consequences, and screening. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(11):1150–6.

Moore AA, Endo JO, Carter MK. Is there a relationship between excessive drinking and functional impairment in older persons? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(1):44–9.

Holbrook TL, Barrett-Connor E, Wingard DL. A prospective population-based study of alcohol use and non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):902–9.

Cook B, Winokur G, Garvey M, Beach V. Depression and previous alcoholism in the elderly. Brit J Psychiatr. 1991;158(1):72–5.

Moore AA, Whiteman EJ, Ward KT. Risks of combined alcohol/medication use in older adults. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2007;5(1):64–74.

Adams W, Yuan Z, Barboriak J, Rimm A. Alcohol-related hospitalizations of elderly people. Prevalence and geographic variation in the untied states. JAMA. 1993;270(10):1222–5.

Moore AA, Morton SC, Beck JC, et al. A new paradigm for alcohol use in older persons. Med Care. 1999;37(2):165–79.

Fink A, Morton SC, Beck JC, et al. The alcohol-related problems survey: identifying hazardous and harmful drinking in older primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1717–22.

Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S, Thavorncharoensap M, Teerawattananon Y, Patra J. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2223–33.

Fink A, Beck JC, Wittrock MC. Informing older adults about non-hazardous, hazardous, and harmful alcohol use. Patient Educ Couns. 2001;45(2):133–41.

Fink A, Morton SC, Beck JC, et al. The alcohol-related problems survey: Identifying hazardous and harmful drinking in older primary care patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1717–22.

Moore AA, Beck JC, Babor TF, Hays RD, Reuben DB. Beyond alcoholism: identifying older, at-risk drinkers in primary care. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63(3):316–24.

Moos RH, Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos BS. High-risk alcohol consumption and late-life alcohol use problems. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(11):1985–91.

Lemke S, Moos RH. Treatment and outcomes of older patients with alcohol use disorders in community residential programs. J Stud Alcohol. 2003;64(2):219–26.

Karlamangla A, Zhou K, Reuben D, Greendale G, Moore AA. Longitudinal trajectories of heavy drinking in adults in the United States of America. Addiction. 2006;101(1):91–9.

Aira M, Kauhanen J, Larivaara P, Rautio P. Factors influencing inquiry about patients' alcohol consumption by primary health care physicians: qualitative semi-structured interview study. Fam Pract. 2003;20(3):270–5.

National Center on Alcohol and Substance Abuse. Missed opportunity: national survey of primary care physicians and patients on substance abuse. 2000.

Loukissa D. misuse. Under diagnosis of alcohol misuse in the older adult population. British Journal of. Nursing (BJN). 2007;16(20):1254–8.

D'Amico E, Paddock S, Burnam A, Kung F. Identification of and guidance for problem drinking by general medical providers: results from a national survey. Med Care. 2005;43(3):229–36.

Burman M, Kivlahan D, Buchbinder M, et al. Alcohol-related advice for Veterans Affairs primary care patients: Who gets it? Who gives it? J Stud Alcohol. 2004;65(5):621–30.

Moore AA, Hays RD, Reuben DB, Beck JC. Using a criterion standard to validate the alcohol-related problems survey (ARPS): a screening measure to identify harmful and hazardous drinking in older persons. Aging (Milano). 2000;12(3):221–7.

Fink A, Tsai MC, Hays RD, et al. Comparing the alcohol-related problems survey (ARPS) to traditional alcohol screening measures in elderly outpatients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;34(1):55–78.

Oishi SM, Morton SC, Moore AA, et al. Using data to enhance the expert panel process. Int J Technol Assess. 2001;17:125–136.

Kirchner JE, Zubritsky C, Cody M, et al. Alcohol consumption among older adults in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(1):92–7.

Mukamal KJ, Lumley T, Luepker RV, et al. Alcohol consumption in older adults and Medicare costs. Health Care Financ Rev.. 2006;27(3):49–61.

Barrett G. The effect of alcohol on earnings. Econ Rec. 2002;78(1):79–96.

Berger M, Leigh J. The effect of alcohol use on wages. Appl Econ. 1988;20:1343–51.

Hamilton V, Hamilton BH. Alcohol and earnings: Does drinking yield a wage premium? Can J Econ. 1997;30(1):17.

Graubard BI, Korn EL. Predictive margins with survey data. Biometrics. 1999;55(2):652–9.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: a clinician's guide. Updated 2005 edition.

U.S. Census Bureau. American community survey 1-year estimates, 2008. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov. Accessed March 2010.

Del Boca FK, Darkes J. The validity of self-reports of alcohol consumption: state of the science and challenges for research. Addiction. 2003;98(S2):1–12.

U.S. Census Bureau. Current population survey, annual social and economic supplement, 2006. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov. Accessed March 2010.

Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, Denny C, Serdula MK, Marks JS. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA. 2003;289(1):70–5.

Flowers NT, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Elder RW, Shults RA, Jiles R. Patterns of alcohol consumption and alcohol-impaired driving in the United States. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(4):6.

Blazer DG, Wu L-T. The epidemiology of at-risk and binge drinking among middle-aged and elderly community adults: national survey on drug use and health. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166(10):1162–9.

UCLA Center for Health Policy Research. California health interview survey. CHIS 2003 adult public use file, release 1 [computer file]. February 2005.

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 1RO1AA013990 (PI: Ettner). Dr. Moore’s time was additionally supported by the National Institute on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse 1R01AA15957 (PI: Moore). We would like to thank the following: the leadership, research staff and IT staff of Sansum Clinic, in particular Dr. Kurt Ransohoff, Mr. Paul Jaconette, Ms. Chris McNamara, Ms. Linda Chapman and Mr. Tom Colbert; Ms. Deborah Marshall and the UCLA research staff; the Project SHARE health educators; and the members of our Research Advisory Board. Finally, we are indebted to the Sansum Clinic patients and physicians who participated in Project SHARE, without whom the study could not have been conducted.

Conflicts of Interest

None disclosed.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Barnes, A.J., Moore, A.A., Xu, H. et al. Prevalence and Correlates of At-Risk Drinking Among Older Adults: The Project SHARE Study. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 840–846 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1341-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1341-x