Abstract

BACKGROUND

Minority women are more likely than white women to choose tubal sterilization as a contraceptive method. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy may help explain observed racial/ethnic differences in sterilization, but this association has not been investigated.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the associations among race/ethnicity, unintended pregnancy, and tubal sterilization.

DESIGN AND PARTICIPANTS

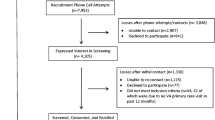

Cross-sectional analysis of data from a nationally representative sample of women aged 15–44 years [65.7% white, 14.8% Hispanic, and 13.9% African American (AA)] who participated in the 2002 National Survey of Family Growth.

MAIN MEASURES

Race/ethnicity, history of unintended pregnancy, and tubal sterilization. A logistic regression model was used to estimate the effect of race/ethnicity on unintended pregnancy while adjusting for socio-demographic variables. A series of logistic regression models was then used to examine the role of unintended pregnancy as a confounder for the relationship between race/ethnicity and sterilization.

KEY RESULTS

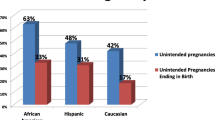

Overall, 40% of white, 48% of Hispanic, and 59% of AA women reported a history of unintended pregnancy. After adjusting for socio-demographic variables, AA women were more likely (OR: 2.0; 95% CI: 1.6–2.4) and Hispanic women as likely (OR: 1.0; 95% CI: 0.80–1.2) as white women to report unintended pregnancy. Sterilization was reported by 29% of women who had ever had an unintended pregnancy compared to 7% of women who reported never having an unintended pregnancy. In unadjusted analysis, AA and Hispanic women had significantly higher odds of undergoing sterilization (OR: 1.5; 95% CI: 1.3–1.9 and OR: 1.4; 95% CI: 1.2–1.7, respectively). After adjusting for unintended pregnancy, this relationship was attenuated and no longer significant (OR: 1.2; 95% CI: 0.95–1.4 for AA women and OR: 1.3; 95% CI: 1.0–1.6 for Hispanic women).

CONCLUSION

Minority women, who more frequently experience unintended pregnancy, may choose tubal sterilization in response to prior experiences with an unintended pregnancy.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Borrero S, Schwarz EB, Reeves MF, Bost JE, Creinin MD, Ibrahim SA. Race, insurance status, and tubal sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:94–100.

Bumpass LL, Thomson E, Godecker AL. Women, men, and contraceptive sterilization. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:937–46.

Chandra A. Surgical sterilization in the United States: prevalence and characteristics, 1965–95. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 1998.

Godecker AL, Thomson E, Bumpass LL. Union status, marital history and female contraceptive sterilization in the United States. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33(9):35–41.

MacKay AP, Kieke BA Jr, Koonin LM, Beattie K. Tubal sterilization in the United States, 1994–1996. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33:161–5.

Mosher WDMG, Chandra A, Abma JC, Wilson SJ. Use of contraception and use of family planning services in the Unites States: 1982–2002. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004.

Piccinino LJ, Mosher WD. Trends in contraceptive use in the United States: 1982–1995. Fam Plann Perspect. 1998;30(46):4–10.

Shapiro TM, Fisher W, Diana A. Family planning and female sterilization in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 1983;17:1847–55.

Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Rodriguez KL, Creinin MD, Arnold RM, Ibrahim SA. “Everything I Know I Learned from My Mother...or Not”: Perspectives of African-American and White Women on Decisions About Tubal Sterilization. J Gen Intern Med. 2008.

Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2113–21.

Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006;38:90–6.

Lepkowski JM, Mosher WD, Davis KE, Grove RM, van Hoewyk J, Willem J. National survey of family growth, cycle 6: Sample design, weighting, imputation, and variance estimation. National center for health statistics. Vital Health Stat. 2006;2(142).

Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield-Timajchy K, et al. The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35:94–101.

Brown S, Eisenberg L. The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1995.

Borrero S, Lin Y, Dehlendorf C, et al. Differences in knowledge may contribute to racial variation in tubal sterilization rates [Abstract P25]. Contraception 2009;80.

Borrero SB, Reeves MF, Schwarz EB, Bost JE, Creinin MD, Ibrahim SA. Race, insurance status, and desire for tubal sterilization reversal. Fertility and sterility. 2007.

Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Tylor LR, Peterson HB. Poststerilization regret: findings from the United States collaborative review of sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:889–95.

Jamieson DJ, Kaufman SC, Costello C, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Peterson HB. A comparison of women’s regret after vasectomy versus tubal sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:1073–9.

Moseman CP, Robinson RD, Bates GW Jr, Propst AM. Identifying women who will request sterilization reversal in a military population. Contraception. 2006;73:512–5.

Schmidt JE, Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Jeng G, Peterson HB. Requesting information about and obtaining reversal after tubal sterilization: findings from the US collaborative review of sterilization. Fertil Steril. 2000;74:892–8.

Borrero S, Schwarz EB, Creinin M, Ibrahim S. The impact of race and ethnicity on receipt of family planning services in the United States. J Women’s Health (2002). 2009;18:91–6.

Forrest JD, Frost JJ. The family planning attitudes and experiences of low-income women. Fam Plann Perspect. 1996;28(77):246–55.

Kaeser L. Title X and the US family planning effort. New York: Alan Guttmacher Institute; 1997.

Landry DJ, Wei J, Frost JJ. Public and private providers’ involvement in improving their patients’ contraceptive use. Contraception. 2008;78:42–51.

Frost JJ. Public or private providers? US women’s use of reproductive health services. Fam Plann Perspect. 2001;33:4–12.

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003.

Eliot J. Fertility control and coercion. Fam Plann Perspect. 1973;5(87):132.

Roberts D. The pill at 40-a new look at a familiar method. Black women and the pill. Fam Plann Perspect. 2000;32:92–3.

Stern AM. Sterilized in the name of public health: race, immigration, and reproductive control in modern California. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1128–38.

Thorburn S, Bogart LM. African American women and family planning services: perceptions of discrimination. Women Health. 2005;42:23–39.

Cheng D, Schwarz EB, Douglas E, Horon I. Unintended pregnancy and associated maternal preconception, prenatal and postpartum behaviors. Contraception. 2009;79:194–8.

Gipson JD, Koenig MA, Hindin MJ. The effects of unintended pregnancy on infant, child, and parental health: a review of the literature. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39:18–38.

Najman JM, Morrison J, Williams G, Andersen M, Keeping JD. The mental health of women 6 months after they give birth to an unwanted baby: a longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 1991;32:241–7.

Wulf D, Donovan P. Women and societies benefit when childbearing is planned. Issues Brief (Alan Guttmacher Inst) 2002;1–4.

Abdel-Tawab N, Roter D. The relevance of client-centered communication to family planning settings in developing countries: lessons from the Egyptian experience. Soc Sci Med. 2002;54:1357–68.

Houle C, Harwood E, Watkins A, Baum KD. What women want from their physicians: a qualitative analysis. Journal of women’s health (2002). 2007;16:543–50.

Weisman CS, Maccannon DS, Henderson JT, Shortridge E, Orso CL. Contraceptive counseling in managed care: preventing unintended pregnancy in adults. Womens Health Issues. 2002;12:79–95.

Oakley D. Rethinking patient counseling techniques for changing contraceptive use behavior. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:1585–90.

Singh R, Frost J, Jordan B, Wells E. Beyond a prescription: strategies for improving contraceptive care. Contraception. 2009;79:1–4.

van Ryn M, Burgess D, Malat J, Griffin J. Physicians’ perceptions of patients’ social and behavioral characteristics and race disparities in treatment recommendations for men with coronary artery disease. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:351–7.

van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians’ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:813–28.

van Ryn M, Fu SS. Paved with good intentions: do public health and human service providers contribute to racial/ethnic disparities in health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:248–55.

van Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Med Care. 2002;40:I140–51.

Afable-Munsuz A, Speizer I, Magnus JH, Kendall C. A positive orientation toward early motherhood is associated with unintended pregnancy among New Orleans youth. Matern Child Health J. 2006;10:265–76.

Gilliam ML, Davis SD, Neustadt AB, Levey EJ. Contraceptive attitudes among inner-city African American female adolescents: Barriers to effective hormonal contraceptive use. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22:97–104.

Guendelman S, Denny C, Mauldon J, Chetkovich C. Perceptions of hormonal contraceptive safety and side effects among low-income Latina and non-Latina women. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4:233–9.

Kendall C, Afable-Munsuz A, Speizer I, Avery A, Schmidt N, Santelli J. Understanding pregnancy in a population of inner-city women in New Orleans-results of qualitative research. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:297–311.

Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Ali N, Posner S, Poindexter AN. Disparities in contraceptive knowledge, attitude and use between Hispanic and non-Hispanic whites. Contraception. 2006;74:125–32.

Thorburn S, Bogart LM. Conspiracy beliefs about birth control: barriers to pregnancy prevention among African Americans of reproductive age. Health Educ Behav. 2005;32:474–87.

Unger JB, Molina GB. Acculturation and attitudes about contraceptive use among Latina women. Health Care Women Int. 2000;21:235–49.

Acknowledgements

This manuscript was made possible by Dr. Borrero’s grant (05 KL2 RR024154-04) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. The content of this publication is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Borrero, S., Moore, C.G., Qin, L. et al. Unintended Pregnancy Influences Racial Disparity in Tubal Sterilization Rates. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 122–128 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1197-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-009-1197-0