Abstract

Background

Latinas are the fastest growing racial ethnic group in the United States and have an incidence of breast cancer that is rising three times faster than that of non-Latino white women, yet their mammography use is lower than that of non-Latino women.

Objectives

We explored factors that predict satisfaction with health-care relationships and examined the effect of satisfaction with health-care relationships on mammography adherence in Latinas.

Design and Setting

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 166 Latinas who were ≥40 years old. Women were recruited from Latino-serving clinics and a Latino health radio program.

Measurements

Mammography adherence was based on self-reported receipt of a mammogram within the past 2 years. The main independent variable was overall satisfaction with one’s health-care relationship. Other variables included: self report of patient-provider communication, level of trust in providers, primary language, country of origin, discrimination experiences, and perceptions of racism.

Results

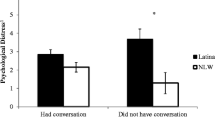

Forty-three percent of women reported very high satisfaction in their health-care relationships. Women with high trust in providers and those who did not experience discrimination were more satisfied with their health-care relationships compared to women with lower trust and who experienced discrimination (p < .01). Satisfaction with the health-care relationship was, in turn, significantly associated with mammography adherence (OR: 3.34, 95% CI: 1.47–7.58), controlling for other factors.

Conclusions

Understanding the factors that impact Latinas’ mammography adherence may inform intervention strategies. Efforts to improve Latina’s satisfaction with physicians by building trust may lead to increased use of necessary mammography.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schettino MR, Hernández-Valero MA, Moguel R, Hajek RA, Jones LA. Assessing breast cancer knowledge, beliefs, and misconceptions among Latinas in Houston, Texas. J Cancer Educ. 2006;21(1 Suppl):S42–46. Spring.

American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures for Hispanic/Latinos 2003–2005. Available at: http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2003HispPWSecured.pdf. Last accessed July 15, 2008.

American Cancer Society: Cancer Facts and Figures for Hispanic/Latinos 2006–2008. Available at http://www.cancer.org/downloads/STT/CAFF2006HispPWSecured.pdf. Last accessed July 15, 2008.

Fernandez M, Tortotero-Luna G, Gold RS. Mammography and Pap test screening among low income foreign born Hispanic women in USA. Cad Saude Publica. 1998;14(Suppl. 3):133–47.

Wu ZH, Black SA, Markides KS. Prevalence and associated factors of cancer screening: why are so many older Mexican American women never screened. Prev Med. 2001;33(4):268–73. Oct.

Gorin SS, Heck JE. Cancer screening among Latino subgroups in the United States. Prev Med. 2005;40(5):515–26. May.

Fernandez ME, Palmer RC, Leong-Wu CA. Repeat mammography screening among low income and minority women; a qualitative study. Cancer Control. 2005;12(Suppl 2):77–83. Nov.

Darnell JS, Chang CH, Calhoun EA. Knowledge about breast cancer and participation in faith-based breast cancer program and other predictors of mammography screening among African-American women and Latinas. Health Promot Pract. 2006;7(3 Suppl):201S–12S. Jul, Epub 2006 Jun 7.

Warren AG, Londono GE, Wessel LA, Warren RD. Breaking down barriers to breast and cervical cancer screening: a university -based prevention program for Latinas. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(3):512–21. Aug.

Mahnken JD, Freeman DH, DiNuzzo AR, Freeman JL. Mammography use among older Mexican-American women: correcting for over-reports of breast cancer screening. Women Health. 2007;45(3):53–64.

Zambrana RE, Breen N, Fox SA, Gutierrez-Mohamed ML. Use of cancer screening practices by Hispanic women: analyses by subgroup. Prev Med. 1999;29(6 Pt 1):466–77. Dec.

Qureshi M, Thacker HL, Litaker DG, Kippes C. Differences in breast cancer screening rates: an issue of ethnicity or socioeconomics? J. Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9(9):1025–31. Nov.

Rodriguez MA, Ward LM, Perez-Stable EJ. Breast and cervical cancer screening: impact of health insurance status, ethnicity, and nativity of Latinas. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(3):235–241. May-Jun.

Borrayo EA, Guarnaccia CA. Differences in Mexican-born and U.S.-born women of Mexican descent regarding factors related to breast cancer screening behaviors. Health Care for Women International21:599–613.

Welsh AL, Sauaua A, Jacobellis J, Min SJ, Byers T. The effect of two church-based interventions on breast cancer screening rates among Medicaid-insured Latinas. Prev Chronic Dis. 2005;2(4):A07. Oct, Epub 2005 Sep 15.

DeLaet DE, Shea S, Carrasquillo O. Receipt of preventive services among privately insured minorities in managed care versus fee-for-service insurance plans. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(6):451–57. Jun.

Garbers S, Jessop DJ, Foti H, Uribelarrea M, Chiasson MA. Barriers to breast cancer screening for low-income Mexican and Dominican women in New York City. J Urban Health. 2003;80(1):81–91. Mar.

Goel MS, Wee CC, McCarthy EP, Davis RB, Ngo-Metzger Q, Phillips RS. Racial and ethnic disparities in cancer screening: the importance of foreign birth as a barrier to care. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(12):1028–35. Dec.

Van Houtven CH, Voils CI, Oddone EZ, et al. Perceived discrimination and reported delay of pharmacy prescriptions and medical tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):578–583. Jul.

Trivedi AN, Ayanian JZ. Perceived discrimination and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):553–8. Jun.

Chen FM, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, Wilson E, Pathman DE. Patients’ beliefs about racism, preferences for physician race, and satisfaction with care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):138–43. Mar-Apr.

Nápoles-Springer AM, Santoyo J, Houston K, Pérez-Stable EJ, Stewart AL. Patients’ perceptions of cultural factors affecting the quality of their medical encounters. Health Expect. 2005;8(1):4–17. Mar.

Kreling BA, Cañar J, Catipon E, et al. Latin American Cancer Research Coalition. Community primary care/academic partnership model for cancer control. Cancer. 2006;107(8 Suppl):2015–22. Oct 15.

Angel RJ, Angel JL, Markides KS. Stability and change in health insurance among older Mexican Americans: longitudinal evidence from the Hispanic established populations for epidemiologic study of the elderly. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(8):1264–71. Aug.

Morales LS, Reise SP, Hays RD. Evaluating the equivalence of health care ratings by whites and Hispanics. Med Care. 2000;38(5):517–27. May.

Zambrana RE. A research agenda on issues affecting poor and minority women: a model for understanding their health needs. Women Health. 1987;12(3–4):137–60.

Ashton CM, Haidet P, Paterniti DA, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in the use of health services: bias, preferences, or poor communication. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(2):146–52. Feb.

Tucker CM, Herman KC, Pedersen TR, Higley B, Montrichard M, Ivery P. Cultural sensitivity in physician-patient relationships: perspectives of an ethnically diverse sample of low-income primary care patients. Med Care. 2003;41(7):859–70. Jul.

Collins KS, Tenney K, Hughes DL. Quality Health Care for African-Americans: findings from the commonwealth fund 2001 health care quality study. New York, NY: The Commonwealth Fund; 2002.

Marshall G. A comparative study of re-attenders and non-re-attenders for second triennial National Breast Screening Programme appointments. J Public Health Med. 1994;16(1):79–86. Mar.

Miller AM, Champion VL. Mammography in women > or = 50 years of age. Predisposing and enabling characteristics. Cancer Nurs. 1993;16(4):260–269. Aug.

Orton M, Fitzpatrick R, Fuller A, Mant D, Mlynek C, Thorogood M. Factors affecting women’s response to an invitation to attend for a second breast cancer screening examination. Br J Gen Pract. 1991;41(349):320—2. Aug.

Peipins LA, Shapiro JA, Bobo JK, Berkowitz Z. Impact of women’s experiences during mammography on adherence to rescreening (United States). Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17(4):439—47. May.

Somkin CP, McPhee SJ, Nguyen T, et al. The effect of access and satisfaction on regular mammogram and Papanicolaou test screening in a multiethnic population. Med Care. 2004;42(9):914—26. Sep.

Crow R, Gage H, Hampson S, et al. The measurement of satisfaction with healthcare: implications for practice from a systematic review of the literature. Health Technol Assess. 2002;6(32):1—244.

Gritz ER, Bastani R. Cancer prevention-behavior changes: the short and the long of it. Prev Med. 1993;22(5):676–88. Sep.

O’Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Prev Med. 2004;38(6):777–85. Jun.

Otero-Sabogal R, Owens D, Canchola J, Golding JM, Tabnak F, Fox P. Mammography rescreening among women of diverse ethnicities: patient, provider, and health care system factors. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004;15(3):390–412. Aug.

Sheppard VB, Zambrana RE, O’Malley AS. Providing health care to low-income women: a matter of trust. Fam Pract. 2004;21(5):484–91. Oct.

Sheppard VB, Figueiredo M, Cañar J, et al. Latina a Latina(SM): developing a breast cancer decision support intervention. Psychooncology. 2007 Jul 13; [Epub ahead of print].

Diaz V. Cultural factors in preventive care: Latinos. Prim Care. 2002;29(3):503–17. Sep, viii.

Lauderdale DS, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Kandula NR. Immigrant perceptions of discrimination in health care: the California Health Interview Survey 2003. Med Care. 2006;44(10):914–20. Oct.

Peragallo NP, Fox PG, Alba ML. Breast care among Latino immigrant women in the U.S. Health Care Women Int. 1998;19(2):165–72. Mar-Apr.

O’Malley AS, Beaton E, Yabroff KR, Abramson R, Mandelblatt J. Patient and provider barriers to colorectal cancer screening in the primary care safety-net. Prev Med. 2004;39(1):56–63. Jul.

Sheppard VB, Cox LS, Kanamori MJ, et al. Latin American Cancer Research Coalition. Brief report: if you build it, they will come: methods for recruiting Latinos into cancer research. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(5):444–7. May.

O’Malley CD, Le GM, Glaser SL, Shema SJ, West DW. Socioeconomic status and breast carcinoma survival in four racial/ethnic groups: a population-based study. Cancer. 2003;97(5):1303–11. Mar 1.

DC Office of Latino Affairs, Latinos in the District of Columbia: Demographics *, Internet - http://ola.dc.gov/ola/cwp/view,a,3,q,568739,olaNav,%7C32535%7C,.asp — Accessed on April 9, 2008.

Bastani R, Marcus AC, Hollatz-Brown A. Screening mammography rates and barriers to use: a Los Angeles County survey. Prev Med. 1991;20(3):350–363. May.

Bastani R, Marcus AC, Maxwell AE, Das IP, Yan KX. Evaluation of an intervention to increase mammography screening in Los Angeles. Prev Med. 1994;23(1):83–90. Jan.

Dimatteo MR, Hays RD, Gritz ER, Bastani R, Crane L, Elashoff R. Patient adherence to cancer control regimens: Scale development and initial validation. Psych Assess. 1993;5(1):102–12.

Bastani R, Maxwell AE, Bradford C, Das IP, Yan KX. Tailored risk notification for women with a family history of breast cancer. Prev Med. 1999;29(5):355–64. Nov.

O’Malley AS, Gonzalez RM, Sheppard VB, Huerta E, Mandelblatt J. Primary care cancer control interventions including Latinos: a review. Am J Prev Med. 2003;25(3):264–71. Oct.

Mandelblatt JS, Gold K, O’Malley AS, et al. Breast and cervix cancer screening among multiethnic women: role of age, health, and source of care. Prev Med. 1999;28(4):418–25. Apr.

O’Malley AS, Forrest CB. Beyond the examination room: primary care performance and the patient-physician relationship for low-income women. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(1):66—74. Jan.

Mojica CM, Bastani R, Ponce NA, Boscardin WJ. Latinas with abnormal breast findings: patient predictors of timely diagnostic resolution. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2007;16(10):1468–77. Dec.

Graves KD, Huerta E, Cullen J, et al. Perceived risk of breast cancer among Latinas attending community clinics: risk comprehension and relationship with mammography adherence. Cancer Causes Control. 2008 Aug 15.

Bird ST, Bogart LM. Perceived race-based and socioeconomic status (SES)-based discrimination in interactions with health care providers. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(3):554–63. Autumn.

LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Boulware LE, Powe NR. The Medical Mistrust Index: A Measure of Mistrust of the Medical Care System 2001.

SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA, 2002–2003.

Bazargan M, Bazargan SH, Calderón JL, Husaini BA, Baker RS. Mammography screening and breast self-examination among minority women in public housing projects: the impact of physician recommendation. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2003;49(8):1213–8. Dec.

Jibaja ML, Kingery P, Neff NE, Smith Q, Bowman J, Holcomb JD. Tailored, interactive soap operas for breast cancer education of high-risk Hispanic women. J Cancer Educ. 2000;15(4):237–42. Winter.

O’Malley AS, Kerner J, Johnson AE, Mandelblatt J. Acculturation and breast cancer screening among Hispanic women in New York City. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(2):219–27. Feb.

Breen N, A Cronin K, Meissner HI, et al. Reported drop in mammography: is this cause for concern. Cancer. 2007;Jun 15;109(12):2405–9.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2007 National Healthcare Disparities Report. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; February 2008. AHRQ Pub. No. 08-0041.

Aldridge ML, Daniels JL, Jukic AM. Mammograms and healthcare access among US Hispanic and non-Hispanic women 40 years and older. Fam Community Health. 2006;29(2):80–8. Apr-Jun.

Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997–1004. May 10.

Gorin SS, Ashford AR, Lantigua R, Desai M, Troxel A, Gemson D. Implementing academic detailing for breast cancer screening in underserved communities. Implement Sci. 2007;2:43. Dec 17.

Flores G. Culture and the patient-physician relationship: achieving cultural competency in health care. J Pediatr. 2000;136(1):14–23. Jan.

Moy B, Park ER, Feibelmann S, Chiang S, Weissman JS. Barriers to repeat mammography: cultural perspectives of African-American, Asian, and Hispanic women. Psychooncology. 2006;15(7):623–34. Jul.

Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient-physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(10):1713–9. Oct.

Derose KP, Baker DW. Limited English proficiency and Latinos’ use of physician services. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(1):76–91. Mar.

Levy-Storms L, Bastani R, Reuben DB. Predictors of varying levels of nonadherence to mammography screening in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):768–773. May.

Gany FM, Herrera AP, Avallone M, Changrani J. Attitudes, knowledge, and health-seeking behaviors of five immigrant minority communities in the prevention and screening of cancer: a focus group approach. Ethn Health. 2006;11(1):19–39. Feb.

Erwin DO, Johnson VA, Trevino M, Duke K, Feliciano L, Jandorf L. A comparison of African American and Latina social networks as indicators for culturally tailoring a breast and cervical cancer education intervention. Cancer. 2007;109(2 Suppl):368–77. Jan 15.

Thompson HS, Valdimarsdottir HB, Winkel G, Jandorf L, Redd W. The Group-Based Medical Mistrust Scale: psychometric properties and association with breast cancer screening. Prev Med. 2004;38(2):209–18. Feb.

O’Malley AS, Forrest CB, Mandelblatt J. Adherence of low-income women to cancer screening recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(2):144–54. Feb.

Yarbroff KS, Mandelblatt JS. Interventions targeted toward patients to increase mammography use. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1999;8(9):749–57. Sep.

Williams SA, Swanson MS. The effect of reading ability and response formats on patients’ abilities to respond to a patient satisfaction scale. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2001;32:60–67.

Terán L, Baezconde-Garbanati L, Márquez M, Castellanos E, Belkić K. On-time mammography screening with a focus on Latinas with low income: a proposed cultural model. Anticancer Res. 2007;27(6C):4325–38. Nov-Dec.

Luquis RR, Villanueva Cruz IJ. Knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions about breast cancer and breast cancer screening among Hispanic women residing in South Central Pennsylvania. J Community Health. 2006;31(1):25–42. Feb.

Wells KJ, Roetzheim RG. Health disparities in receipt of screening mammography in Latinas: a critical review of recent literature. Cancer Control. 2007;14(4):369–79. Oct.

Madlensky L, Vierkant RA, Vachon CM, et al. Preventive health behaviors and familial breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005;14(10):2340–5. Oct.

Koval AE, Riganti AA, Foley KL. CAPRELA (Cancer Prevention for Latinas): findings of a pilot study in Winston-Salem, Forsyth County. N C Med J. 2006;67(1):9–15. Jan-Feb.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all of the women who took time to participate in the study.

Members of the Latin American Cancer Research Coalition who participated in this study included: Janet Cañar, MD, at Spanish Catholic Center, Jyl Pomeroy at Arlington Free Clinic, John Kavanaugh at La Clinica Del Pueblo, and Yosselyn Rodriguez at Washington Cancer institute/Medstar Research Institute.

We acknowledge Michelle Goodman, MA, and Mariano Kanamori for research support and Maria Lopez, Ph.D., for review of the manuscript.

Supported, in part, by ACS grants MRSGT-06-132-01-CPPB (VBS) and MRSGT-05-104-01-CPPB (JW), National Cancer Institute grants UO1 CA86114 (EH, JM), U01-CA114593 (EH, JM), and KO5 CA96940 (JM)

Conflict of Interest Statement

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sheppard, V.B., Wang, J., Yi, B. et al. Are Health-care Relationships Important for Mammography Adherence in Latinas?. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 2024–2030 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0815-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0815-6