Abstract

BACKGROUND

The time course of physicians’ knowledge retention after learning activities has not been well characterized. Understanding the time course of retention is critical to optimizing the reinforcement of knowledge.

DESIGN

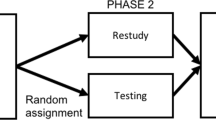

Educational follow-up experiment with knowledge retention measured at 1 of 6 randomly assigned time intervals (0–55 days) after an online tutorial covering 2 American Diabetes Association guidelines.

PARTICIPANTS

Internal and family medicine residents.

MEASUREMENTS

Multiple-choice knowledge tests, subject characteristics including critical appraisal skills, and learner satisfaction.

RESULTS

Of 197 residents invited, 91 (46%) completed the tutorial and were randomized; of these, 87 (96%) provided complete follow-up data. Ninety-two percent of the subjects rated the tutorial as “very good” or “excellent.” Mean knowledge scores increased from 50% before the tutorial to 76% among those tested immediately afterward. Score gains were only half as great at 3–8 days and no significant retention was measurable at 55 days. The shape of the retention curve corresponded with a 1/4-power transformation of the delay interval. In multivariate analyses, critical appraisal skills and participant age were associated with greater initial learning, but no participant characteristic significantly modified the rate of decline in retention.

CONCLUSIONS

Education that appears successful from immediate posttests and learner evaluations can result in knowledge that is mostly lost to recall over the ensuing days and weeks. To achieve longer-term retention, physicians should review or otherwise reinforce new learning after as little as 1 week.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Davis D, O’Brien MA, Freemantle N, Wolf FM, Mazmanian P,Taylor-Vaisey A. Impact of formal continuing medical education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA. 1999;282(9):867–74.

Choudhry NK, Fletcher RH, Soumerai SB. Systematic review: the relationship between clinical experience and quality of health care. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142(4):260–73.

Eisenberg JM. An educational program to modify laboratory use by house staff. J Med Educ. 1977;52(7):578–81.

Evans CE, Haynes RB, Birkett NJ, Gilbert JR, Taylor DW, Sackett DL, et al. Does a mailed continuing education program improve physician performance? Results of a randomized trial in antihypertensive care. JAMA. 1986;255(4):501–4.

Marinopoulos SS, Dorman T, Ratanawongsa N, Wilson LM, Ashar BH, Magaziner JL, et al. Effectiveness of Continuing Medical Education. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2007. Evidence Report AHRQ Publication No. 07-E006, January.

Bjork EL, Bjork RA. On the adaptive aspects of retrieval failure in autobiographical memory. In: Grueneberg MM, Morris PE, Sykes RN, eds. Practical Aspects of Memory: Current Research and Issues: Vol 1 Memory in Everyday Life. New York: Wiley; 1988.

Bjork RA, Bjork EL. A new theory of disuse and an old theory of stimulus fluctuation. In: Healy A, Kosslyn S, Shiffrin R, eds. From Learning Processes to Cognitive Processes: Essays in honor of William K Estes. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence; 1992.

Schmidt RA, Bjork RA. New conceptualizations of practice: common principles in three paradigms suggest new concepts for training. Psychol Sci. 1992;3(4):207–17.

Anderson JR, editor. Cognitive psychology and its implications. New York: Freeman; 1995.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84(2):191–215.

Chumley-Jones HS, Dobbie A, Alford CL. Web-based learning: sound educational method or hype? A review of the evaluation literature. Acad Med. 2002;77(10 Suppl):S86–93.

Cook DA, Dupras DM. A practical guide to developing effective web-based learning. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):698–707.

Embi PJ, Bowen JL, Singer E. A Web-based curriculum to improve residents’ education in outpatient medicine. Acad Med. 2001;76(5):545.

Sisson SD, Hughes MT, Levine D, Brancati FL. Effect of an internet-based curriculum on postgraduate education. A multicenter intervention. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(5 Pt 2):505–9.

Cook DA, Dupras DM, Thompson WG, Pankratz VS. Web-based learning in residents’ continuity clinics: a randomized, controlled trial. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):90–7.

Bennett NL, Casebeer LL, Kristofco RE, Strasser SM. Physicians’ internet information-seeking behaviors. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2004;24(1):31–8.

Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. ACCME Annual Report Data 2004; 2005.

van Braak JP, Goeman K. Differences between general computer attitudes and perceived computer attributes: development and validation of a scale. Psychol Rep. 2003;92(2):655–60.

Chin MH, Cook S, Jin L, Drum ML, Harrison JF, Koppert J, et al. Barriers to providing diabetes care in community health centers. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(2):268–74.

Cabana MD, Rand C, Slish K, Nan B, Davis MM, Clark N. Pediatrician self-efficacy for counseling parents of asthmatic children to quit smoking. Pediatrics. 2004;113(1 Pt 1):78–81.

Arauz-Pacheco C, Parrott MA, Raskin P. Hypertension management in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S65–7.

Haffner SM. Dyslipidemia management in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(Suppl 1):S68–71.

Kern DE, Thomas PA, Howard DM, Bass EB. Goals and Objectives. Curriculum Development for Medical Education: A Six Step Approach. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1998.

Bell DS, Fonarow GC, Hays RD, Mangione CM. Self-study from web-based and printed guideline materials. A randomized, controlled trial among resident physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(12):938–46.

Matts JP, Lachin JM. Properties of permuted-block randomization in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1988;9(4):327–44.

Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297.

Rubin DC, Wenzel AE. One hundred years of forgetting: a quantitative description of retention. Psychol Rev. 1996;103(4):734–60.

Bjork RA. Memory and metamemory considerations in the training of human beings. In: Metcalfe J, Shimamura A, eds. Metacognition: Knowing about Knowing. Cambridge, MA: MIT; 1994:185–205.

Chung S, Mandl KD, Shannon M, Fleisher GR. Efficacy of an educational Web site for educating physicians about bioterrorism. Acad Emerg Med. 2004;11(2):143–8.

Beal T, Kemper KJ, Gardiner P, Woods C. Long-term impact of four different strategies for delivering an on-line curriculum about herbs and other dietary supplements. BMC Med Educ. 2006;6:39.

Fordis M, King JE, Ballantyne CM, Jones PH, Schneider KH, Spann SJ, et al. Comparison of the instructional efficacy of internet-based CME with live interactive CME workshops: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;294(9):1043–51.

Gais S, Born J. Declarative memory consolidation: mechanisms acting during human sleep. Learn Mem. 2004;11(6):679–85.

Chen FM, Bauchner H, Burstin H. A call for outcomes research in medical education. Acad Med. 2004;79(10):955–60.

Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Generalist Physician Faculty Scholars Program (San Antonio, TX, USA) and the Diabetes Action Research and Education Foundation (Washington DC, USA). Dr. Mangione received additional support from the National Institute on Aging through the UCLA Resource Center for Minority Aging Research (NIA AG-02-004). Dr. Bazargan received additional support from the National Center for Research Resources (G12 RR 03026-16). We are grateful to Drs. Diana Echeverry, Lisa Skinner, and Mayer Davidson for the assistance with developing educational content and to Drs. Jodi Friedman, Michelle Bholat, Mohammed Farooq, and Nancy Hanna for facilitating our access to residents in their training programs.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Bell has performed consulting for Google. This activity is related to physician education. Mr. Harless is currently employed as a software engineer by the Walt Disney Corporation; his contributions to this manuscript are solely his own and are unrelated to his employment.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Trial registration: NCT00470860, ClinicalTrials.gov, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix 1.

(PDF 30 KB)

Appendix

Appendix

The LOFTS interactive tutorial

This screen-capture image illustrates the operation of the main interactive tutorial portion of the longitudinal online focused tutorial system (LOFTS). The upper frame of the tutorial window shows 1 pretest question at a time with feedback on the user’s pretest response shown to the right. Above the question, the relevant learning objective is stated in italics. The lower frame of the tutorial window contains the guideline document in its entirety with the relevant passages highlighted. In this example, the user had answered the question incorrectly, resulting in feedback that encouraged a careful review of the guideline passages and instructions to then try another answer.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bell, D.S., Harless, C.E., Higa, J.K. et al. Knowledge Retention after an Online Tutorial: A Randomized Educational Experiment among Resident Physicians. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 1164–1171 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0604-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0604-2