Summary

Objective

Little is known about associations between psychiatric comorbidity and hospital mortality for acute medical conditions. This study examined if associations varied according to the method of identifying psychiatric comorbidity and agreement between the different methods.

Patients/Participants

The sample included 31,218 consecutive admissions to 168 Veterans Affairs facilities in 2004 with a principle diagnosis of congestive heart failure (CHF) or pneumonia. Psychiatric comorbidity was identified by: (1) secondary diagnosis codes from index admission, (2) prior outpatient diagnosis codes, (3) and prior mental health clinic visits. Generalized estimating equations (GEE) adjusted in-hospital mortality for demographics, comorbidity, and severity of illness, as measured by laboratory data.

Measurements and Main Results

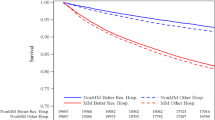

Rates of psychiatric comorbidities were 9.0% using inpatient diagnosis codes, 27.4% using outpatient diagnosis codes, and 31.0% using mental health visits for CHF and 14.5%, 33.1%, and 34.1%, respectively, for pneumonia. Agreement was highest for outpatient codes and mental health visits (κ = 0.51 for pneumonia and 0.50 for CHF). In GEE analyses, the adjusted odds of death for patients with psychiatric comorbidity were lower when such comorbidity was identified by mental health visits for both pneumonia (odds ratio [OR] = 0.85; P = .009) and CHF (OR = 0.70; P < .001) and by inpatient diagnosis for pneumonia (OR = 0.63; P ≤ .001) but not for CHF (OR = 0.75; P = .128). The odds of death were similar (P > .2) for psychiatric comorbidity as identified by outpatient codes for pneumonia (OR = 1.04) and CHF (OR = 0.93).

Conclusions

The method used to identify psychiatric comorbidities in acute medical populations has a strong influence on the rates of identification and the associations between psychiatric illnesses with hospital mortality.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kessler RC, Chiu TC, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, Severity, and Comorbidity of 12-Month DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–27.

Kisely S, Smith M, Lawrence D, et al. Mortality in individuals who have had psychiatric treatment: population-based study in Nova Scotia. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187:552–8.

Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF. Medical comorbidity in women and men with schizophrenia: a population-based controlled study. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1133–7.

Daumit GL, Pronovost PJ, Anthony CB, et al. Adverse events during medical and surgical hospitalizations for persons with schizophrenia. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:267–72.

Jaffe AS, Krumholz HM, Catellier DJ, et al. Prediction of medical morbidity and mortality after acute myocardial infarction in patients at increased psychosocial risk in the Enhancing Recovery in Coronary Heart Disease Patients (ENRICHD) study. Am Heart J. 2006;152:126–35.

Lesperance F, Frasure-Smith N, Juneau M, et al. Depression and 1-year prognosis in unstable angina. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1354–60.

Druss BG, Bradford WD, Rosenheck RA, et al. Quality of medical care and excess mortality in older patients with mental disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:565–72.

Young JK, Foster DA. Cardiovascular procedures in patients with mental disorders. JAMA. 2000;283:3198. author reply 3198–9.

Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283:506–11.

Lawrence DM, Holman CD, Jablensky AV, et al. Death rate from ischaemic heart disease in Western Australian psychiatric patients 1980–1998. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:31–6.

Maynard C, Lowy E, Rumsfeld J, et al. The prevalence and outcomes of in-hospital acute myocardial infarction in the Department of Veterans Affairs Health System. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1410–6.

Elixhauser A, Steiner C, Harris D, et al. Comorbidity measures for use with administrative data. Med Care. 1998;36:8–27.

Knaus WA, Wagner DP, Draper EA, et al. The APACHE III prognostic system. Risk prediction of hospital mortality for critically ill hospitalized adults. Chest. 1991;100:1619–36.

Iezzoni LI. The risks of risk adjustment. JAMA. 1997;278:1600–7.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

Iezzoni LI, Foley SM, Daley J, Hughes J, Fishe, et al. Comorbidities, complications, and coding bias. Does the number of diagnosis codes matter in predicting in-hospital mortality? JAMA. 1992;267:2197–203.

Jencks SF, Williams DK, Kay TL. Assessing hospital-associated deaths from discharge data. The role of length of stay and comorbidities. JAMA. 1988;260:2240–6.

Ottervanger JP, Armstrong P, Barnathan ES, et al. Association of revascularisation with low mortality in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndrome, a report from GUSTO IV-ACS. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:1494–501.

Jones LE, Carney CP. Mental disorders and revascularization procedures in a commercially insured sample. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:568–76.

Petersen LA, Normand SL, Druss BG, et al. Process of care and outcome after acute myocardial infarction for patients with mental illness in the VA health care system: are there disparities? Health Serv Res. 2003;38:41–63.

Glasser M, Stearns JA. Unrecognized mental illness in primary care. Another day and another duty in the life of a primary care physician. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:862–4.

Hsia DC, Krushat WM, Fagan AB, et al. Accuracy of diagnostic coding for Medicare patients under the prospective-payment system. N Engl J Med. 1988;318(6):352–5.

Hannan EL, Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Doran D, et al. Provider profiling and quality improvement efforts in CABG surgery: the effect on short-term mortality among Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care. 2003;41(10):1164–72.

Vaughan-Sarrazin MS, Hannan EL, Gormley CJ, et al. Mortality in Medicare beneficiaries following coronary artery bypass graft surgery in states with and without certificate of need regulation. JAMA. 2002;288(15):1859–66.

Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Policy and Planning. Program Evaluation of Cardiac Care Programs in the Veterans Health Administration. Part 1: Acute Myocardial Infarction (AMI) and Percutaneous Coronary Interventions (PCI) Cohort Analyses. Contract Number V101 (93) 1444. 4-11-2003. Washington DC: Department of Veterans Affairs. http://www.va.gov/opp/organizations/progeval.htm (Report).

Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Services Research Administration. A Report on the Quality of Surgical Care in the Department of Veterans Affairs: The Phase III Report. R&D no. IL 10-87-9. 4-21-1991. Washington, DC: Administrator of Veterans Affairs; 1991(findings also found in Stremple JH, Bross DS, Davis CL, McDonald DO. Comparison of postoperative mortality and morbidity in VA and nonfederal hospitals. J Surg Res. 1994;56:405–16.) (Report).

Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Services Research Administration. A Report on the Quality of Surgical Care in the Department of Veterans Affairs: The Phase II Report. R&D no. IL 10-87-8. 4-12-1989. Washington, DC: Administrator of Veterans Affairs; 1989(findings also found in Stremple JH, Bross DS, Davis CL, McDonald DO. Comparison of postoperative mortality in VA and private hospitals. Ann Surg. 1993;217:272–85.) (Report).

Krakauer H, Bailey RC, Skellan KJ, et al. Evaluation of the HCFA model for the analysis of mortality following hospitalization. Health Serv Res. 1992;27:317–35.

Ash AS, Posner MA, Speckman J, et al. Using claims data to examine mortality trends following hospitalization for heart attack in Medicare. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(5):1253–62.

Pine M, Norusis M, Jones B, et al. Predictions of hospital mortality rates: a comparison of data sources. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:347–54.

Pine M, Jordan HS, Elixhauser A, et al. Enhancement of claims data to improve risk adjustment of hospital mortality. JAMA. 2007;297:71–6.

Felker BL, Chaney E, Rubenstein LV, et al. Developing effective collaboration between primary care and mental health providers. Primary care companion. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(1):12–16.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted and completed by only those authors listed on the title page. No other authors contributed in a significant manner to this work.

The research reported here was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Service through the Center for Research in the Implementation of Innovative Strategies in Practice (CRIISP) (HFP 04-149). Dr. Abrams is a fellow associate supported by additional VA funding through the Office of Academic Affairs. This work was presented at the Annual Society of General Internal Medicine conference in Toronto, Canada on April 27, 2007.

Conflict of Interest

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs. The authors report no conflicts of interest in regards to this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Abrams, T.E., Vaughan-Sarrazin, M. & Rosenthal, G.E. Variations in the Associations Between Psychiatric Comorbidity and Hospital Mortality According to the Method of Identifying Psychiatric Diagnoses. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 317–322 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0518-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0518-z