Abstract

BACKGROUND

Rigorous guideline development methods are designed to produce recommendations that are relevant to common clinical situations and consistent with evidence and expert understanding, thereby promoting guidelines’ acceptability to providers. No studies have examined whether this technical quality consistently leads to acceptability.

OBJECTIVE

To examine the clinical acceptability of guidelines having excellent technical quality.

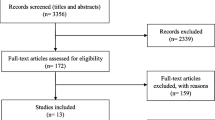

DESIGN AND MEASUREMENTS

We selected guidelines covering several musculoskeletal disorders and meeting 5 basic technical quality criteria, then used the widely accepted AGREE Instrument to evaluate technical quality. Adapting an established modified Delphi method, we assembled a multidisciplinary panel of providers recommended by their specialty societies as leaders in the field. Panelists rated acceptability, including “perceived comprehensiveness” (perceived relevance to common clinical situations) and “perceived validity” (consistency with their understanding of existing evidence and opinions), for ten common condition/therapy pairs pertaining to Surgery, physical therapy, and chiropractic manipulation for lumbar spine, shoulder, and carpal tunnel disorders.

RESULTS

Five guidelines met selection criteria. Their AGREE scores were generally high indicating excellent technical quality. However, panelists found 4 guidelines to be only moderately comprehensive and valid, and a fifth guideline to be invalid overall. Of the topics covered by each guideline, panelists rated 50% to 69% as “comprehensive” and 6% to 50% as “valid”.

CONCLUSION

Despite very rigorous development methods compared with guidelines assessed in prior studies, experts felt that these guidelines omitted common clinical situations and contained much content of uncertain validity. Guideline acceptability should be independently and formally evaluated before dissemination.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Mosca L, Linfante AH, Benjamin EJ, et al. National study of physician awareness and adherence to cardiovascular disease prevention guidelines. Circulation. 2005;111(4):499–510.

Bauer MS. A review of quantitative studies of adherence to mental health clinical practice guidelines. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2002;10(3):138–53.

Cruz-Correa M, Gross CP, Canto MI, et al. The impact of practice guidelines in the management of Barrett esophagus: a national prospective cohort study of physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(21):2588–95.

Switzer GE, Halm EA, Chang CC, Mittman BS, Walsh MB, Fine MJ. Physician awareness and self-reported use of local and national guidelines for community-acquired pneumonia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(10):816–23.

Christakis DA, Rivara FP. Pediatricians’ awareness of and attitudes about four clinical practice guidelines. Pediatrics. 1998;101(5):825–30.

Cabana MD, Rand CS, Powe NR, Wu AW, Wilson MH, Abboud PA. Why don't physicians follow clinical practice guidelines? A framework for improvement. JAMA. 1999;282(15):1458–65.

Ward MM, Vaughn TE, Uden-Holman T, Doebbeling BN, Clarke WR, Woolson RF. Physician knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding a widely implemented guideline. J Eval Clin Pract. 2002;8(2):155–62.

Cabana MD, Ebel BE, Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Rubin HR, Rand CS. Barriers pediatricians face when using asthma practice guidelines. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2000;154(7):685–93.

Committee to Advise the Public Health Service on Clinical Practice Guidelines, Institute of Medicine. In: Field MJ, Lohr KN, eds. Clinical Practice Guidelines: Directions for a New Program. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1990.

Shaneyfelt TM, Mayo-Smith MF, Rothwangl J. Are guidelines following guidelines? The methodological quality of clinical practice guidelines in the peer-reviewed medical literature. JAMA. 1999;281(20):1900–5.

The AGREE Collaboration. The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument. Available at: http://www.agreetrust.org/docs/AGREE_Instrument_English.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2007.

The AGREE Collaboration. Development and validation of an international appraisal instrument for assessing the quality of clinical practice guidelines: the AGREE project. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(1):18–23.

Burgers JS. Guideline quality and guideline content: are they related? Clin Chem. 2006;52(1):3–4.

Shiffman RN, Shekelle P, Overhage JM, Slutsky J, Grimshaw J, Deshpande AM. Standardized reporting of clinical practice guidelines: a proposal from the Conference on Guideline Standardization. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(6):493–8.

United States National Guideline Clearinghouse Inclusion Criteria. Available at: http://www.guideline.gov/about/inclusion.aspx. Accessed July 6, 2006.

State of California. Assembly Bill 749 (Calderon), Workers’ Compensation: Administration and Benefits; 2002.

State of California. Senate Bill 228 (Alarcón), Workers’ Compensation; 2003.

State of California. Senate Bill 899 (Poochigan), Workers’ Compensation; 2004.

Hutchings A, Raine R, Sanderson C, Black N. An experimental study of determinants of the extent of disagreement within clinical guideline development groups. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(4):240–5.

Nuckols TK, Wynn BO, Lim Y, et al. Evaluating Medical Treatment Guideline Sets for Injured Workers in California. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2005. MG-400-ICJ.

Grol R, Cluzeau FA, Burgers JS. Clinical practice guidelines: towards better quality guidelines and increased international collaboration. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(Suppl):S4–8.

Watine J, Friedberg B, Nagy E, et al. Conflict between guideline methodologic quality and recommendation validity: a potential problem for practitioners. Clin Chem. 2006;52(1):65–72.

Vlayen J, Aertgeerts B, Hannes K, Sermeus W, Ramaekers D. A systematic review of appraisal tools for clinical practice guidelines: multiple similarities and one common deficit. Int J Qual Health Care. 2005;17(3):235–42.

The AGREE Collaboration. The Appraisal of Guidelines for Research & Evaluation (AGREE) Instrument Training Manual. Available at: http://www.agreetrust.org/docs/AGREE_INSTR_MANUAL.pdf. Accessed March 22, 2007.

Fitch K, Bernstein SJ, Aguilar MD, et al. The RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method User’s Manual. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2001. MR-1269-DG-XII/RE. Available at: http://www.rand.org/publications/MR/MR1269/.

Shekelle PG. The appropriateness method. Med Decis Making. 2004;24(2):228–31.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–74.

Shekelle PG, Kahan JP, Bernstein SJ, Leape LL, Kamberg CJ, Park RE. The reproducibility of a method to identify the overuse and underuse of medical procedures. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(26):1888–95.

Shekelle PG, Chassin MR, Park RE. Assessing the predictive validity of the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method criteria for performing carotid endarterectomy. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1998;14(4):707–27.

Higashi T, Shekelle PG, Adams JL, Kamberg CJ, Roth CP, Solomon DH, Reuben DB, Chiang L, MacLean CH, Chang JT, Young RT, Saliba DM, Wenger NS. Quality of care is associated with survival in vulnerable older patients. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Aug 16;143(4):274–81.

Wynn BO, Bergamo G, Shaw RN, Mattke S, Dembe A. Medical Care Provided California’s Injured Workers: An Overview of the Issues. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation; 2006. WR-394-ICJ.

Hasenfeld R, Shekelle PG. Is the methodological quality of guidelines declining in the U.S.? Comparison of the quality of U.S. agency for health care policy and research (AHCPR) guidelines with those published subsequently. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(6):428–34.

Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Cleary PD. Quality of health care. Part 2: measuring quality of care. N Engl J Med. 1996;335(13):966–70.

Donabedian A. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring, Vol. 1. The Definition of Quality and Approaches to its Assessment. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1980.

Donabedian A. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring, Vol. 2. The Criteria and Standards of Quality. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1982.

Donabedian A. Explorations in Quality Assessment and Monitoring, Vol. 3. The Methods and Findings of Quality Assessment and Monitoring: An Illustrated Analysis. Ann Arbor, MI: Health Administration Press; 1985.

Shekelle PG, Woolf SH, Eccles M, Grimshaw J. Clinical guidelines: developing guidelines. BMJ. 1999;318(7183):593–6.

Maue SK, Segal R, Kimberlin CL, Lipowski EE. Predicting physician guideline compliance: an assessment of motivators and perceived barriers. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(6):383–91.

Mottur-Pilson C, Snow V, Bartlett K. Physician explanations for failing to comply with “best practices”. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4(5):207–13.

Grol R, Dalhuijsen J, Thomas S, Veld C, Rutten G, Mokkink H. Attributes of clinical guidelines that influence use of guidelines in general practice: observational study. BMJ. 1998;317(7162):858–61.

Burgers JS, Grol RP, Zaat JO, Spies TH, van der Bij AK, Mokkink HG. Characteristics of effective clinical guidelines for general practice. Br J Gen Pract. 2003;53(486):15–9.

Shiffman RN, Dixon J, Brandt C, et al. The GuideLine Implementability Appraisal (GLIA): development of an instrument to identify obstacles to guideline implementation. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2005;5:23–34.

Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, et al. Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Practice Guidelines: how quickly do guidelines become outdated? JAMA. 2001;286(12):1461–7.

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Guidelines and support documents for hip pain, knee injury, knee osteoarthritis, low back pain/sciatica, shoulder pain and wrist pain. 2001–2003.

American College of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. Occupational Medicine Practice Guidelines: Evaluation and Management of Common Health Problems and Functional Recovery in Workers, Second Edition. Beverly Farms, Massachusetts; 2004.

Intracorp. Intracorp Optimal Treatment Guidelines. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; 2003. Available at: http://www.intracorp.com.

McKesson. InterQual Care Management Criteria for Workers’ Comp & Clinical Evidence Summaries. (Formerly QualityFirst® Workers’ Compensation/Disability Guidelines). Newton, Massachusetts. 2004.

Work Loss Data Institute. Official Disability Guides (ODG), Treatment in Workers’ Compensation. San Diego, CA; 2004. Available at: http://www.worklossdata.com.

Acknowledgements

Christine Baker, M.A., Executive Officer of the California Commission on Health and Safety and Workers’ Compensation and Anne Searcy, M.D., Medical Director of the California Division of Workers’ Compensation participated in the study conception and design (specifically, choosing the inclusion criteria for the guidelines). Paul G. Shekelle, M.D, Ph.D., The RAND Corporation, Santa Monica; Division of General Internal Medicine and Health Services Research, Department of Medicine David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles; and VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, California, provided comments on a draft of this manuscript. This study was sponsored by the California Department of Industrial Relations (the Division of Workers Compensation and the California Commission on Health and Safety and Workers’ Compensation). The RAND Corporation provided support for the preparation of this manuscript. Although Christine Baker and Anne Searcy, Division of Workers’ Compensation participated in the study conception and design, data acquisition, analysis, and preparation of this manuscript were completely independent of the funders.

Conflicts of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This document includes content previously published in a RAND report, available online at: http://www.rand.org/publications/MG/MG400/.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nuckols, T.K., Lim, YW., Wynn, B.O. et al. Rigorous Development does not Ensure that Guidelines are Acceptable to a Panel of Knowledgeable Providers. J GEN INTERN MED 23, 37–44 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0440-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0440-9