Background

Clinician’s knowledge of a woman’s cancer family history (CFH) and counseling about health-related behaviors (HRB) is necessary for appropriate breast cancer care.

Objective

To evaluate whether clinicians solicit CFH and counsel women on HRB; to assess relationship of well visits and patient risk perception or worry with clinician’s behavior.

Design

Cross-sectional population-based telephone survey.

Participants

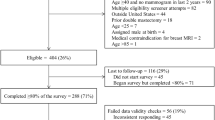

Multiethnic sample; 1,700 women from San Francisco Mammography Registry with a screening mammogram in 2001–2002.

Measurements

Predictors: well visit in prior year, self-perception of 10-year breast cancer risk, worry scale. Outcomes: Patient report of clinician asking about CFH in prior year, or ever counseling about HRB in relation to breast cancer risk. Multivariate models included age, ethnicity, education, language of interview, insurance/mammography facility, well visit, ever having a breast biopsy/follow-up mammography, Gail-Model risk, Jewish heritage, and body mass index.

Results

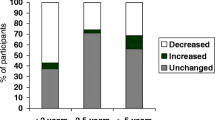

58% reported clinicians asked about CFH; 33% reported clinicians ever discussed HRB. In multivariate analysis, regardless of actual risk, perceived risk, or level of worry, having had a well visit in prior year was associated with increased odds (OR = 2.3; 95% CI 1.6, 3.3) that a clinician asked about CFH. Regardless of actual risk of breast cancer, a higher level of worry (OR = 1.9; 95% CI 1.4, 2.6) was associated with increased odds that a clinician ever discussed HRB.

Conclusions

Clinicians are missing opportunities to elicit family cancer histories and counsel about health-related behaviors and breast cancer risk. Preventive health visits offer opportunities for clinicians to address family history, risk behaviors, and patients’ worries about breast cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Sifri R, Gangadharappa S, Acheson LS. Identifying and testing for hereditary susceptibility to common cancers. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(6):309–26.

Summerton N, Garrood PV. The family history in family practice: a questionnaire study. Fam Pract. 1997;14(4):285–8.

Gramling R, Nash J, Siren K, Eaton C, Culpepper L. Family physician self-efficacy with screening for inherited cancer risk. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(2):130–2.

Acheson LS, Wiesner GL, Zyzanski SJ, Goodwin MA, Stange KC. Family history-taking in community family practice: implications for genetic screening. Genet Med. 2000;2(3):180–5.

Pyeritz RE. Family history and genetic risk factors: forward to the future. JAMA. 1997;278(15):1284–5.

Korde LA, Calzone KA, Zujewski J. Assessing breast cancer risk: genetic factors are not the whole story. Postgrad Med. 2004;116(4):6–8, 11–4, 19–20.

Colditz GA, Hankinson SE. The Nurses’ Health Study: lifestyle and health among women. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5(5):388–96.

McTiernan A. Behavioral risk factors in breast cancer: can risk be modified? Oncologist. 2003;8(4):326–34.

McTiernan A, Kooperberg C, White E, et al. Recreational physical activity and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: the Women’s Health Initiative Cohort Study. JAMA. 2003;290(10):1331–6.

Hamajima N, Hirose K, Tajima K, et al. Alcohol, tobacco and breast cancer—collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 58,515 women with breast cancer and 95,067 women without the disease. Br J Cancer. 2002;87(11):1234–45.

Murff HJ, Spigel DR, Syngal S. Does this patient have a family history of cancer? An evidence-based analysis of the accuracy of family cancer history. JAMA. 2004;292(12):1480–9.

Medalie JH, Zyzanski SJ, Langa D, Stange KC. The family in family practice: is it a reality? J Fam Pract. 1998;46(5):390–6.

Haas JS, Kaplan CP, Gregorich SE, Perez-Stable EJ, Des Jarlais G. Do physicians tailor their recommendations for breast cancer risk reduction based on patient’s risk? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(4):302–9.

Watson E, Clements A, Yudkin P, et al. Evaluation of the impact of two educational interventions on GP management of familial breast/ovarian cancer cases: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2001;51(471):817–21.

Jaen CR, Stange KC, Nutting PA. Competing demands of primary care: a model for the delivery of clinical preventive services. J Fam Pract. 1994;38(2):166–71.

Walsh JM, McPhee SJ. A systems model of clinical preventive care: an analysis of factors influencing patient and physician. Health Educ Q. 1992;19(2):157–75.

Woo B, Woo B, Cook EF, Weisberg M, Goldman L. Screening procedures in the asymptomatic adult. Comparison of physicians’ recommendations, patients’ desires, published guidelines, and actual practice. JAMA. 1985;254(11):1480–4.

DiLorenzo TA, Schnur J, Montgomery GH, Erblich J, Winkel G, Bovbjerg DH. A model of disease-specific worry in heritable disease: the influence of family history, perceived risk and worry about other illnesses. J Behav Med. 2006;29(1):37–49.

Frojd C, Von Essen L. Is doctors’ ability to identify cancer patients’ worry and wish for information related to doctors’ self-efficacy with regard to communicating about difficult matters? Eur J Cancer Care. (Engl) 2006;15(4):371–8.

Gramling R, Anthony D, Lowery J, et al. Association between screening family medical history in general medical care and lower burden of cancer worry among women with a close family history of breast cancer. Genet Med. 2005;7(9):640–5.

Des Jarlais G, Kaplan CP, Haas JS, Gregorich SE, Perez-Stable EJ, Kerlikowske K. Factors affecting participation in a breast cancer risk reduction telephone survey among women from four racial/ethnic groups. Prev Med. 2005;41(3–4):720–7.

Haas JS, Kaplan CP, Des Jarlais G, Gildengoin V, Perez-Stable EJ, Kerlikowske K. Perceived risk of breast cancer among women at average and increased risk. J Women’s Health. (Larchmt) 2005;14(9):845–51.

Kaplan CP, Haas JS, Perez-Stable EJ, et al. Breast cancer risk reduction options: awareness, discussion, and use among women from four ethnic groups. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15(1):162–6.

Livaudais JC, Kaplan CP, Haas JS, Perez-Stable EJ, Stewart S, Jarlais GD. Lifestyle behavior counseling for women patients among a sample of California physicians. J Women’s Health. (Larchmt) 2005;14(6):485–95.

San Francisco Mammography Registry. In. San Franicsco; 2006.

Costantino JP, Gail MH, Pee D, et al. Validation studies for models projecting the risk of invasive and total breast cancer incidence. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(18):1541–8.

Gail MH, Brinton LA, Byar DP, et al. Projecting individualized probabilities of developing breast cancer for white females who are being examined annually. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1989;81(24):1879–86.

AHRQ. Screening for Breast Cancer. In: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force; 2002.

Lerman C, Daly M, Sands C, et al. Mammography adherence and psychological distress among women at risk for breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85(13):1074–80.

Lerman C, Lustbader E, Rimer B, et al. Effects of individualized breast cancer risk counseling: a randomized trial. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1995;87(4):286–92.

Likert RA. A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Arch Psychol. 1932;140.

Nunnally JC. Measurement of Sentiments. In: Psychometric Theory: McGraw-Hill; 1978:602–7.

StataCorp. Stata’s User Guide Version 9. College Station, Texas: Stata Press; 2005.

Murff HJ, Byrne D, Haas JS, Puopolo AL, Brennan TA. Race and family history assessment for breast cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(1):75–80.

Kaplan CP, Haas JS, Perez-Stable EJ, Des Jarlais G, Gregorich SE. Factors affecting breast cancer risk reduction practices among California physicians. Prev Med. 2005;41(1):7–15.

Bernstein AB, Hing E, Moss Aj, Allen KF, Siller AB, RB T. Health care in America: Trends in utilization. In: National Center for Health Statistics; 2003.

Forrest CB, Whelan EM. Primary care safety-net delivery sites in the United States: a comparison of community health centers, hospital outpatient departments, and physicians’ offices. JAMA. 2000;284(16):2077–83.

CDC. Family History Public Health Initiative. In: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Office of Genomics and Disease Prevention.

Grande GE, Hyland F, Walter FM, Kinmonth AL. Women’s views of consultations about familial risk of breast cancer in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;48(3):275–82.

Nelson HD, Huffman LH, Fu R, Harris EL. Genetic risk assessment and BRCA mutation testing for breast and ovarian cancer susceptibility: systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(5):362–79.

Warner E, Carroll JC, Heisey RE, et al. Educating women about breast cancer. An intervention for women with a family history of breast cancer. Can Fam Physician. 2003;49:56-63.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with the support of the California Breast Cancer Research Program (grant number 6PB-0053) and the NCI-funded Breast Cancer Surveillance Consortium Cooperative Agreement (U01CA63740).

Potential Financial Conflicts of Interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karliner, L.S., Napoles-Springer, A., Kerlikowske, K. et al. Missed Opportunities: Family History and Behavioral Risk Factors in Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Among a Multiethnic Group of Women. J GEN INTERN MED 22, 308–314 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0087-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-006-0087-y