Abstract

Introduction

Although asymptomatic pancreatic lesions (APLs) are being discovered incidentally with increasing frequency, their true significance remains uncertain. Treatment decisions pivot off concerns for malignancy but at times might be excessive. To understand better the role of surgery, we scrutinized a spectrum of APLs as they presented to our surgical practice over defined periods.

Methods

All incidentally identified APLs that were operated upon during the past 5 years were clinically and pathologically annotated. Among features evaluated were method/reason for detection, location, morphology, interventions, and pathology. For the past 2 years, since our adoption of the Sendai guidelines for cystic lesions, we scrutinized our approach to all patients presenting with APLs, operated upon or not.

Results

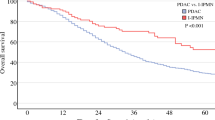

Over 5 years, APLs were identified most frequently during evaluation of: genitourinary/renal (16%), asymptomatic rise in liver function tests (LFTs; 13%), screening/surveillance (7%), and chest pain (6%). APLs occurred throughout the pancreas (body/tail 63%; head/uncinate 37%) with 48% being solid. One hundred ten operations were performed with no operative mortality including 89 resections (distal 57; Whipple 32) and 21 other procedures. Morbidity was equivalent or better than those cases performed for symptomatic lesions during the same time frame. During these 5 years, APLs accounted for 23% of all pancreatic resections we performed. In all, 22 different diagnoses emerged including non-malignant intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm (IPMN; 17%), serous cystadenoma (14%), and neuroendocrine tumors (13%), while 6% of patients had >1 distinct pathology and 12% had no actual pancreatic lesion at all. Invasive malignancy was present 17% of the time, while carcinoma in situ or metastases was identified in an additional eight patients. Thus, the overall malignancy rate for APLs equals 24% and these patients were substantially older (68 vs 58 years; p = 0.003). An asymptomatic rise in LFTs correlated significantly (p = 0.009) with malignancy. Furthermore, premalignant pathology was found an additional 47% of the time. Seven patients ultimately chose an operation over continued observation for radiographic changes (mean 2.6 years), but none had cancer. In the last 2 years, we have evaluated 132 new patients with APLs, representing 47% of total referrals for pancreatic conditions. Nearly half were operated upon, with a 3:2 ratio of solid to cystic lesions. This differs significantly (p = 0.037) from the previous 3 years (2:3 ratio), reflecting tolerance for cysts <3 cm and side-branch IPMN. Surgery was undertaken more often when a solid APL was encountered (74%) than for cysts (32%). Some solid APLs were actually unresectable cancers. Due to anxiety, two patients requested an operation over continued observation, and neither had cancer.

Conclusion

APLs occur commonly, are often solid, and reflect a spectrum of diagnoses. Sendai guidelines are not transferable to solid masses but have safely refined management of cysts. An asymptomatic rise in LFTs cannot be overlooked nor should a patient or doctor’s anxiety, given the prevalence of cancer in APLs.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Schaberg FJ Jr, Doyle MB, Chapman WC, Vollmer CM, Zalieckas JM, Birkett DH, Miner TJ, Mazzaglia PJ. Incidental findings at surgery. Curr Probl Surg 2008;45(5):325–374. doi:10.1067/j.cpsurg.2008.01.004.

Singh M, Maitra A. Precursor lesions of pancreatic cancer: molecular pathology and clinical implications. Pancreatology 2007;7:9–19. doi:10.1159/000101873.

Kostiuk TS. Observation of pancreatic incidentaloma. Klin Khir 2001;9:62–63.

Fitzgerald TL, Smith AJ, Ryan M, Atri M, Wright FC, Law CHL. Surgical treatment of incidentally identified pancreatic masses. Can J Surg 2003;46(6):413–418.

Bruzoni M, Johnston E, Sasson AR. Pancreatic incidentalomas: clinical and pathologic spectrum. The Am J Surg 2008;195:45(5):329–332. May.

Winter JM, Cameron JL, Lillemoe KD, Campbell KA, Chang D, Riall TS, Coleman JA, Sauter PK, Canto M, Hruban RH, Schulick RD, Choti MA, Yeo CJ. Periampullary and pancreatic incidentaloma—single institution’s experience with an increasingly common diagnosis. Ann Surg 2006;243(5):673–683. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000216763.27673.97.

Fernández-del Castillo C, Targarona J, Thayer SP, Rattner DW, Brugge WR, Warshaw AL. Incidental pancreatic cysts—clinicopathologic characteristics and comparison with symptomatic patients. Arch Surg 2003;138:427–434. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.4.427.

Tanaka M, Chari S, Adsay V, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Falconi M, Shimizu M, et al. International consensus guidelines for management of intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms and mucinous cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. Pancreatology 2006;6:17–32. doi:10.1159/000090023.

Katz MHG, Pisters PWT, Evans DB, Sun CC, Lee JE, Fleming JB, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, Crane CH, Wolff RA, Varadhachary GR, Hwang R. Borderline resectable pancreatic cancer: the importance of this emerging stage of disease. J Am Coll Surg 2008;206:833–848. doi:10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.12.020.

Vollmer CM, Pratt WB, Vanounou T, Maithel SK, Callery MP. Quality assessment in high-acuity surgery: volume and mortality are not enough. Arch Surg 2007;142(4):371–380. doi:10.1001/archsurg.142.4.371.

Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001.

Pratt WB, Maithel SK, Vanounou T, Huang ZS, Callery MP, Vollmer CM. Clinical and economic validation of the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (ISGPF) classification scheme. Ann Surg 2007;245(3):443–451. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000251708.70219.d2.

Brugge WR, Lauwers GY, Sahani D, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL. Cystic neoplasms of the pancreas. N Engl J Med 2004;351:1218–1226. doi:10.1056/NEJMra031623.

Kitagawa Y, Traverso LW, et al. Mucus is a predictor of better prognosis and survival in patients with intraductal papillary mucinous tumor of the pancreas. JOGS 2003;7:12–19.

Strasberg SM, Middleton WD, Teefey SA, McNevin MS, Drebin JA. Management of diagnostic dilemmas of the pancreas by ultrasonographically guided laparoscopic biopsy. Surgery 1999;126(4):736–741.

Handrich SJ, Hough DM, Fletcher JG, Sarr MG. The natural history of the incidentally discovered small simple pancreatic cyst: long-term follow-up and clinical implications. AJR 2005;184:20–23.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Discussion

The Incidental Asymptomatic Pancreatic Lesion: Nuisance or Threat

Craig P. Fischer, M.D. (Houston, TX): Once again, a nice paper from a high volume pancreatic surgery center in Boston. Asymptomatic pancreatic lesions are increasingly observed because of high utilization of cross-sectional imaging for unrelated abdominal complaints. As a result, physicians are often in a quandary—is this lesion really a threat? The International Association of Pancreatology met in Sendai Japan, and published guidelines for management of cystic lesions of the pancreas in 2004. A larger percentage of cystic lesions are now being observed when specific criteria are met. We don’t have similar guidelines for solid, asymptomatic pancreatic lesions. These authors examine patients referred with asymptomatic pancreatic lesions—and examine two time periods—before and after the international consensus publications from Sendai. They show a very high percentage of solid lesions that are asymptomatic and nearly 17% of all resected specimens harbored invasive malignancy. We are still left however with the same quandary—how do preoperatively determine who is at risk, and who can be observed.

My first question. The frequency of invasive disease observed in solid APLs was about 30%. Are there any solid pancreatic lesions which should be observed, and if so, is EUS with FNA a good discriminate test? Or is the false negative rate high enough that all suitable patients should undergo operation.

My second question. Since the Sendai criteria, you have observed more pancreatic cysts that are less than 3 cm. What criteria do you use for surgery in the patients who are being observed? Is it change in diameter, the patient becomes symptomatic? Development of a mural nodule?

Lastly, how do you balance the risk and benefit ratio for patients with asymptomatic lesions? An 86-year-old patient with multiple comorbid conditions is not somebody you really want to operate on. Are you observing any of these folks, and if so, are you going to report back to our association the natural history of what happens to those patients.

Thanks very much.

Teviah E. Sachs (Boston, MA): Very poignant questions, Dr. Fischer. Certainly your first question, the solid lesions that are being observed, we do have a few. In the study, as I mentioned, 74% of those patients who had solid lesions were resected, and the ones that weren’t were often due to comorbidities. However, in some of our patients who are being followed after receiving EUS analysis for solid lesions, it is often they need to have something like a splenule workup, so that some of those lesions that wouldn’t need to be operated upon due to the possible morbidity of resection. We find EUS very useful in categorizing these lesions.

As for the last 2 years, in the patients were following whose lesions are under 3 cm, we are using radiographic findings as the major determinant in deciding on who to subsequently resect. Certainly changes in size on imaging or the new appearance of any solid elements or nodules would heighten our concern and perhaps lead to the resection.

And as for the risk/benefits ratio in those patients who have multiple comorbidities, the resections can be morbid. Although we see some patients develop pancreatic fistulas, our rate for clinically significant pancreatic fistulas is lower in these incidentally discovered lesions (8%), than it is in our total resection cohort (14%). Still, those that have comorbidities are being followed, and we will certainly report back, because this subset of patients is a valuable asset to determine the nature and progression of this process and they may dictate how we treat our future patients with either observation or resection.

Lygia Stewart, M.D. (San Francisco, CA): I know that you are using EUS. Have you used any of the markers like CEA in your analysis in deciding whether to operate?

Dr. Sachs: Absolutely, absolutely. CEA and amylase are both levels at which we look. We do not place much value on aspirate CA 19-9 levels. Interestingly, of the patients who received EUS, those with elevated CEA levels have always been mucinous on final pathology, and so it is a very, very beneficial test for us at our center. Cytology was less specific, actually, although when diagnosis of malignancy on cytology was found, that always correlated with invasive disease. Furthermore, the finding of cytologic atypia was always associated with a malignant precursor lesion.

Carlos Fernandez Del Castillo, M.D. (Boston, MA): Congratulations on a very nice presentation, and I concur with you that we are all living an epidemic of incidentally discovered cystic lesions of the pancreas. What I am really struck with, and I think this paper is provocative and a little bit different than what we are seeing, is the number of solid incidentally discovered lesions. At Mass General we just finished looking at 4 years, 401 cystic lesions; 71% of them are incidental findings. That is 280 cystic lesions. In your experience, you said that half of the incidentally discovered lesions were solid. There is absolutely no way that there are 280, or even a fraction of those, solid. We do frequently see neuroendocrine tumors as an incidental finding, but I was very surprised that you had 16% of adenocarcinomas in your series. So could you tell us how were those solid lesions identified, because this is very different from the experience of other centers.

Dr. Sachs: Very, very good question, and certainly in the literature, we were surprised to find a paucity of understanding of these solid incidental lesions, which is the impetus for our paper. As you mentioned, to date, most of the attention for this problem has focused on cystic diseases of the pancreas. Interestingly, I think that the presentations, as I illustrated earlier, were equally distributed for solid and cystic lesions. The specific exams acquired for solid lesions did not differ from the cystic ones. I don’t know why we are seeing more and more of these as solid lesions asymptomatically, but we certainly are. You would think that a solid lesion within the pancreas would cause symptoms prior to these patients coming in, but as we showed not all of these are malignant or even invasive.

But as for the adenocarcinoma patients, the real issue that we bring up here is that the asymptomatic rise in liver function tests really does correlate with adenocarcinoma, and so it must be used proficiently by clinicians throughout medicine.

Dr. Fernandez Del Castillo: I would be careful, though, to call that asymptomatic, because if your bilirubin is elevated, even if the patient does not have clinical jaundice, unless the patient had the studies done as part of a routine physical, he or she really has some symptoms. So it may not be the right thing to put those patients in that category.

Dr. Sachs: That is true, that is true. Hyperbilirubinemia was encountered in very few of those patients with elevated liver function tests, but they did not manifest clinically as jaundice. We actually had two patients in our symptomatic cohort who presented to their primary care physicians with elevated liver function tests prior to presenting to us with symptoms. We elected to classify them as symptomatic, and therefore they were excluded from the cohort presented today. In those two cases, their liver function test elevation was chalked up to medications that they were taking. Had they been recognized earlier, they might have been operated on earlier as well.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sachs, T., Pratt, W.B., Callery, M.P. et al. The Incidental Asymptomatic Pancreatic Lesion: Nuisance or Threat?. J Gastrointest Surg 13, 405–415 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-008-0788-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-008-0788-0