Abstract

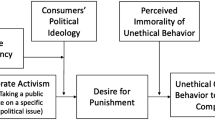

Consumer resistance against corporate wrongdoing is of growing relevance for business research, as well as for firms and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). Considering Fournier’s (1998) classification of consumer resistance, this study focuses on boycotting, negative word-of-mouth (WOM), and protest behavior, and these behavioral patterns can be assigned to the so-called “active rebellion” subtype of consumer resistance. Existing literature has investigated the underlying motives for rebellious actions such as boycotting. However, research offers little insight into the extent to which motivational processes are regulated by individual ethical ideology. To fill this gap in existing research, this study investigates how resistance motives and ethical ideology jointly influence individual willingness to engage in rebellion against unethical firm behavior. Based on a sample of German residents, PLS path analyses reveal direct effects of resistance motives, counterarguments, and ethical ideologies as well as moderating effects of ethical ideologies, which vary across different forms of rebellion. First, the results indicate that relativism (idealism) is more relevant in the context of boycott participation and protest behavior (negative WOM). Second and contrary to previous findings, this study reveals a positive effect of relativism on behavioral intentions. Third, individuals’ ethical ideologies do not moderate the effect of motivation to and arguments against engaging in negative WOM. On the contrary, the empirical analysis reveals significant moderating effects of relativism and idealism with regard to the effects of resistance motives and counterarguments on boycott and protest intention. Directions for future research and practical implications are discussed based on the study results.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Firms can also serve as substitute targets in so-called secondary boycotts (Schrempf-Stirling et al. 2013). For example, Chinese nationalists called for a boycott of the French retail group Carrefour and the French luxury brand Louis Vuitton after activists advocating for Tibetan independence disturbed the 2008 Summer Olympics torch relay in Paris (Pál 2009).

A confirmatory factor analysis conducted with SPSS AMOS that considered one covariance between two error terms showed an acceptable global fit for the three dependent variables’ measurement models (χ2 = 123.30, p < 0.01; χ2/df = 3.08; Hoelter’s N = 217; GFI = 0.95; AGFI = 0.92; NFI = 0.95; TLI = 0.95; CFI = 0.96; RMSEA = 0.07).

The authors evaluated the quality of measurement considering a confirmatory factor analysis conducted with SPSS AMOS. The global fit for the refined measurement of ethical ideologies can be regarded good to very good (χ2 = 42.88, p < 0.05; χ2/df = 1.72; Hoelter’s N = 434; GFI = 0.98; AGFI = 0.96; NFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.98; CFI = 0.99; RMSEA = 0.04).

In order to see whether the differences in path coefficients are significant, we performed a “virtual” multi-group analysis based on the Welch-Satterthwaite test (Chin 2000). Each of the tests considers our sample twice as virtual subgroups. The analysis revealed that the difference in consumer motives’ path coefficients between the boycott model and the WOM model is significant (t value = 2.687, df = 838, p < 0.01). The same holds true for the difference between the boycott model and the protest model (t value = 3.960, df = 838, p < 0.01).

The Welch–Satterthwaite test reveals significant differences in counterarguments’ path coefficients between the boycott model and the WOM model (t value = −2.263, df = 838, p < 0.05) as well as between the boycott model and the protest model (t-value = –1.980, df = 838, p < 0.05).

References

Alexandrov A, Lilly B, Babakus E (2013) The effects of social-and self-motives on the intentions to share positive and negative word of mouth. J Acad Market Sci 41(5):531–546

Al-Khatib JA, D’Auria Stanton A, Rawwas MYA (2005) Ethical segmentation of consumers in developing countries: a comparative analysis. Int Market Rev 22(2):225–246

Al-Khatib JA, Al-Habib MI, Bogari N, Salamah N (2016) The ethical profile of marketing negotiators. Bus Ethics Eur Rev 25(2):172–186

Allensbach ID (2015) Anzahl der Personen in Deutschland, die beim Einkaufen darauf achten, dass die Produkte aus fairem Handel (Fair Trade) stammen, von 2012 bis 2015 (in Millionen). http://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/264566/umfrage/kaeufertypen–bevorzugung-von-produkten-aus-fairem-handel-fair-trade/. Accessed 17 November 2015

Angelis MD, Bonezzi A, Peluso AM, Rucker DD, Costabile M (2012) On braggarts and gossips: a self-enhancement account of word-of-mouth generation and transmission. J Mark Res 49(4):551–563

Bandura A (1990) Selective activation and disengagement of moral control. J Soc Issues 46(1):27–46

Barnett T, Bass K, Brown G (1996) Religiosity, ethical ideology, and intentions to report a peer’s wrongdoing. J Bus Ethics 15(11):1161–1174

Barnett T, Bass K, Brown G, Hebert FJ (1998) Ethical ideology and the ethical judgments of marketing professionals. J Bus Ethics 17(7):715–723

Bass K, Barnett T, Brown G (1998) The moral philosophy of sales managers and its influence on ethical decision making. J Pers Selling Sales Manag 18(2):1–17

Becker JM, Klein K, Wetzels M (2012) Hierarchical latent variable models in PLS-SEM: guidelines for using reflective-formative type models. Long Range Plan 45(5–6):359–394

Bentham J (1879) An introduction to the principles of morals and legislation. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Bray J, John N, Kilburn D (2011) An exploratory study into the factors impeding ethical consumption. J Bus Ethics 98(4):597–608

Brunk KH (2012) Un/ethical company and brand perceptions: conceptualising and operationalising consumer meanings. J Bus Ethics 111(4):551–565

Cadogan JW, Lee N, Tarkiainen A, Sundqvist S (2009) Sales manager and sales team determinants of salesperson ethical behaviour. Eur J Mark 43(7):907–937

Cherrier H (2009) Anti-consumption discourses and consumer-resistant identities. J Bus Res 62(2):181–190

Cherrier H, Black IR, Lee M (2011) Intentional non-consumption for sustainability: consumer resistance and/or anti-consumption? Eur J Mark 45(11):1757–1767

Cheung CMK, Lee MKO (2012) What drives consumers to spread electronic word of mouth in online consumer-opinion platforms? Decis Support Syst 53(1):218–225

Chin WW (2000) Frequently asked questions—partial least squares & PLS-graph. http://disc-nt.cba.uh.edu/chin/plsfaq.htm. Accessed 03 April 2017

Crane A, Matten D (2010) Business ethics, 3rd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Cui CC, Mitchell V, Schlegelmilch BB, Cornwell B (2005) Measuring consumers’ ethical position in Austria, Britain, Brunei, Hong Kong, and USA. J Bus Ethics 62(1):57–71

Davis RM (1979) Comparison of consumer acceptance of rights and responsibilities. In: Ackerman NM (ed) Ethics and the consumer interest. American Council on Consumer Interest, Columbia, pp 68–70

Davis MA, Andersen MG, Curtis MB (2001) Measuring ethical ideology in business ethics: a critical analysis of the ethics position questionnaire. J Bus Ethics 32(1):35–53

DePaulo PJ (1986) Ethical perceptions of deceptive bargaining tactics used by salespersons and consumers a double standard. In: Saegert JG (ed) Proceedings of the division of consumer psychology. American Psychological Association, Washington, pp 201–203

Donaldson T (1996) Values in tension: ethics away from home. Harvard Bus Rev 74(5):48–62

Dovidio JF, Pilivian JA, Gaertner SL, Schroeder DA, Clark RD III (1991) The arousal: cost-reward model and the process of intervention: a review of the evidence. In: Clark MS (ed) Prosocial behavior. Sage, Newbury Park, pp 86–118

Elliot AJ, Friedman R (2007) Approach-avoidance: a central characteristic of personal goals. In: Little BR, Salmela-Aro KE, Phillips SD (eds) Personal project pursuit: goals, action, and human flourishing. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers, Mahwah, pp 97–118

Erffineyer RC, Keillor BD, LeClair DT (1999) An empirical investigation of Japanese consumer ethics. J Bus Ethics 18(1):35–50

Fiske ST, Neuberg SL (1990) A continuum of impression formation, from category-based to individuating processes: influences of information and motivation on attention and interpretation. Adv Exp Soc Psychol 23(C):1–74

Fletcher J (1966) Situation ethics—the new morality. Westminster John Knox Press, London

Forsyth DR (1980) A taxonomy of ethical ideologies. J Pers Soc Psychol 39(1):175–184

Forsyth DR (1992) Judging the morality of business practices: the influence of personal moral philosophies. J Bus Ethics 11(5):461–470

Forsyth DR (n.d.) Ethics position questionnaire. https://donforsyth.wordpress.com/ethics/ethics-position-questionnaire/. Accessed 11 November 2016

Forsyth DR, Nye JL, Kelley K (1988) Idealism, relativism and the ethic of caring. J Psychol 122(3):243–248

Forum Fairer Handel (2010) Trends und Entwicklungen im Fairen Handel 2010. https://www.forum-fairer-handel.de/fileadmin/user_upload/dateien/jpk/vergangene_jpks/factsheet_jpk_2010.pdf. Accessed 25 April 2016

Fournier S (1998) Consumer resistance: societal motivations, consumer manifestations, and implications in the marketing domain. In: Alba JW, Hutchinson JW (eds) NA—advances in consumer research, vol 25. Association for Consumer Research, Provo, pp 88–90

Friedman M (1985) Consumer boycotts in the United States, 1970–1980: contemporary events in historical perspective. J Consum Aff 19(1):96–117

Friedman M (1999) Consumer boycotts. Routledge, New York

Froelich KA (1999) Diversification of revenue strategies: evolving resource dependence in nonprofit organizations. Nonprof Volunt Sect Q 28(3):246–268

Garrett DE (1987) The effectiveness of marketing policy boycotts: environmental opposition to marketing. J Mark 51(2):46–57

Gilligan C (1982) In a different voice: psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press, Cambridge (MA), London

Grappi S, Romani S, Bagozzi RP (2013) Consumer response to corporate irresponsible behavior: moral emotions and virtues. J Bus Res 66(10):1814–1821

Habermas J (1991) Erläuterungen zur Diskursethik. Suhrkamp, Frankfurt am Main

Hair JF Jr, Hult GTM, Ringle CM, Sarstedt M (2016) A primer on partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM), 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Hastings SE, Finegan JE (2011) The role of ethical ideology in reactions to injustice. J Bus Ethics 100(4):689–703

Healy L (2007) Universalism and cultural relativism in social work ethics. Int Soc Work 50(1):11–26

Henle CA, Giacolone RA, Jurkiewicz CL (2005) The role of ethical ideology in workplace deviance. J Bus Ethics 56(3):219–230

Hennig-Thurau T, Walsh G (2003) Electronic word-of-mouth: motives for and consequences of reading customer articulations on the internet. Int J Electron Comm 8(2):51–74

Henseler J, Ringle CM, Sinkovics RR (2009) The use of partial least squares path modeling in international marketing. Adv Int Mar 20(1):277–319

Hirschman AO (1970) Exit, voice, and loyalty: responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, London

Hoffmann S (2011) Anti-consumption as a means to save jobs. Eur J Mark 45(11/12):1702–1714

Hoffmann S, Müller S (2009) Consumer boycotts due to factory relocation. J Bus Res 62(2):239–247

Hollander JA, Einwohner RL (2004) Conceptualizing resistance. Sociol Forum 19(4):533–554

Holzmann R (2015) Wirtschaftsethik. Springer Gabler, Wiesbaden

Hong C, Hu WM, Prieger JE, Zhu D (2011) French automobiles and the Chinese boycotts of 2008: politics really does affect commerce. BE J Econom Anal Policy 11(1):1–51

Hull CL (1932) The goal-gradient hypothesis and maze learning. Psychol Rev 39(1):25–43

Hunt SD, Vitell S (1986) A general theory of marketing ethics. J Macromarketing 6(1):5–16

International Cocoa Organization (2016) Supply and demand—latest figures from the quarterly bulletin of cocoa statistics. http://www.icco.org/about-us/international-cocoa-agreements/cat_view/30-related-documents/47-statistics-supply-demand.html. Accessed 06 June 2016

Ipsos (2014) Ipsos Global Trends Survey 2014. https://www.statista.com/statistics/353645/consumer-activism-in-germany/. Accessed 24 November 2016

John A, Klein J (2003) The boycott puzzle: consumer motivations for purchase sacrifice. Manag Sci 49(9):1196–1209

Kant I (1870) Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten. In: Kirchmann JH (ed) Philosophische Bibliothek oder Sammlung der Hauptwerke der Philosophie alter und neuer Zeit, 28. L. Heimann, Berlin

Kivetz R, Urminsky O, Zheng Y (2006) The goal-gradient hypothesis resurrected: purchase acceleration, illusionary goal progress, and customer retention. J Mark Res 43(1):39–58

Klein JG (2001) Exploring motivations for participation in a consumer boycott. Dissertation, London Business School

Klein JG, Smith NC, John A (2002) Why we boycott: consumer motivations for boycott participation and marketer responses. London Business School, Centre for Marketing Working Paper 02–701

Klein JG, Smith NC, John A (2004) Why we boycott: consumer motivations for boycott participation. J Mark 68(3):92–109

Kohlberg L (1983) Essays in moral development. Harper & Row, New York

Koku PS, Akhigbe A, Springer TM (1997) The financial impact of boycotts and threats of boycotts. J Bus Res 40(1):15–20

Kozinets RV, Handelman JM (1998) Ensouling consumption: a netnographic exploration of boycotting behavior. In: Alba JW, Hutchinson JW (eds) NA—advances in consumer research, vol 25. Association for Consumer Research, Provo, pp 475–480

Leary MR, Knight PD, Barnes BD (1986) Ethical ideologies of the Machiavellian. Pers Soc Psychol B 12(1):75–80

Lee M, Roux D, Cherrier H, Cova B (2011) Anti-consumption and consumer resistance: concepts, concerns, conflicts and convergence. Eur J Mark 45(11/12):1680–1687

Lindenmeier J, Schleer C, Pricl D (2012) Consumer outrage: emotional reactions to unethical corporate behavior. J Bus Res 65(9):1364–1373

Locke J (1821) Two treatises on government, Book II. R. Butler, etc., London

Lu LC, Lu CJ (2010) Moral philosophy, materialism, and consumer ethics: an exploratory study in Indonesia. J Bus Ethics 94(2):193–210

Marta JKM, Attia A, Singhapakdi A, Atteya N (2003) A comparison of ethical perceptions and moral philosophies of American and Egyptian business students. Teach Bus Ethics 7(1):1–20

Maslow AH (1943) A theory of human motivation. Psychol Rev 50(4):370–396

McHoskey JW (1996) Authoritarianism and ethical ideology. J Soc Psychol 136(6):709–717

Merriam-Webster (n.d.) Machiavellianism. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/Machiavellian. Accessed 16 November 2016

Mill JS (1901) Utilitarianism. Longmans, Green and Company, London

Mudrack PE (2005) Utilizing moral reasoning: the role of deference to authority. In: Proceedings of the administrative sciences association of Canada, Toronto (CA)

Muncy JA, Eastman JK (1998) Materialism and consumer ethics: an exploratory study. J Bus Ethics 17(2):137–145

Nebenzahl ID, Jaffe ED, Kavak B (2001) Consumers’ punishment and rewarding process via purchasing behavior. Teach Bus Ethics 5(3):283–305

Newstead S, Franklyn Stokes A, Armstead P (1996) Individual differences in student cheating. J Educ Psychol 87(2):229–241

Nicholls AJ (2002) Strategic options in fair trade retailing. Int J Retail Distrib Manag 30(1):6–17

Pál N (2009) From Starbucks to Carrefour: consumer boycotts, nationalism and taste in contemporary China. PORTAL J Multidiscip Stud 6(2):1–12

Park H (2005) The role of idealism and relativism as dispositional characteristics in the socially responsible decision-making process. J Bus Ethics 56(1):81–98

Penaloza L, Price LL (1993) Consumer resistance: a conceptual overview. In: McAlister L, Rothschild ML (eds) NA—advances in consumer research, vol 20. Association for Consumer Research, Provo, pp 123–128

Perugini M, Bagozzi RP (2001) The role of desires and anticipated emotions in goal-directed behaviours: broadening and deepening the theory of planned behavior. Br J Soc Psychol 40(1):79–98

Poster M (1992) The question of agency: Michael de Certeau and the history of consumerism. Diacritics 22(2):94–107

Raby R (2005) What is resistance? J Youth Stud 8(2):151–171

Randall DM, Fernandes MF (1991) The social desirability response bias in ethics research. J Bus Ethics 10(11):805–817

Rawwas MYA, Isakson H (2000) Ethics of tomorrow’s business managers: the influence of personal beliefs and values, individual characteristics, and the opportunity to cheat. J Educ Bus 75(6):321–330

Rawwas MYA, Vitell SJ, Al-Khatib JA (1994) Consumer ethics: the possible effects of terrorism and civil unrest on the ethical values of consumers. J Bus Ethics 13(3):223–231

Rawwas MYA, Al Khatib JA, Vitell SJ (2004) Academic dishonesty: a crosscultural comparison of U.S. and Chinese marketing students. J Mark Educ 26(1):89–100

Rawwas MYA, Arjoon S, Sidani Y (2013) An introduction in epistemology to business ethics: a study of marketing middle-managers. J Bus Ethics 117(3):525–539

Redfern K, Crawford J (2004) An empirical investigation of the ethics position questionnaire in the People’s Republic of China. J Bus Ethics 50(3):199–210

Reidenbach RE, Robin DP (1990) Toward the development of a multidimensional scale for improving evaluations of business ethics. J Bus Ethics 9(8):639–653

Richins ML (1983) Negative word-of-mouth by dissatisfied consumers: a pilot study. J Mark 47(1):68–78

Ringle CM, Wende S, Becker JM (2015) SmartPLS 3. Bönningstedt: SmartPLS. http://www.smartpls.com

Ritson M, Dobscha S (1999) Marketing heretics: resistance is/is not futile. In: Arnould EJ, Scott LM (eds) NA—advances in consumer research, vol 26. Association for Consumer Research, Provo, p 159

Rudmin FW, Richins ML (1992) Meaning, measure, and morality of materialism. Association for Consumer Research, Provo

Schepers DH (2006) The impact of NGO network conflict on the corporate social responsibility strategies of multinational corporations. Bus Soc 45(3):282–299

Schlenker BR, Forsyth DR (1977) On the ethics of psychological research. J Exp Soc Psychol 13(4):369–396

Schrempf-Stirling J, Bosse DA, Harrison JS (2013) Anticipating, preventing, and surviving secondary boycotts. Bus Horiz 56(5):573–582

Sen S, Gürhan-Canli Z, Morwitz VG (2001) Withholding consumption: a social dilemma perspective on consumer boycotts. J Consum Res 28(3):399–417

Shaub MK, Finn DW, Munter P (1993) The effects of auditors’ ethical orientation on commitment and ethical sensitivity. Behav Res Account 5(1):145–169

Singhapakdi A, Kraft KL, Vitell SJ, Rallapalli KC (1995) The perceived importance of ethics and social responsibility on organizational effectiveness: a survey of marketers. J Acad Market Sci 23(1):49–56

Singhapakdi A, Vitell SJ, Franke GR (1999) Antecedents, consequences, and mediating effects of perceived moral intensity and personal moral philosophies. J Acad Market Sci 27(1):19–36

Singhapakdi A, Salyachivin S, Virakul B, Veerayangkur V (2000) Some important factors underlying ethical decision making of managers in Thailand. J Bus Ethics 27(3):271–284

Singhapakdi A, Gopinath M, Marta JKM, Carter LL (2008) Antecedents and consequences of perceived importance of ethics in marketing situations: a study of Thai business people. J Bus Ethics 81(4):887–904

Smith NC (1990) Morality and the market: consumer pressure for corporate accountability. Routledge, London

Smith NC, Cooper-Martin E (1997) Ethics and target marketing: the role of product harm and consumer vulnerability. J Mark 61(3):1–20

Sørensen MJ, Vinthagen S (2012) Nonviolent resistance and culture. Peace Change 37(3):444–470

Sparks JR, Hunt SD (1998) Marketing researcher ethical sensitivity: conceptualization, measurement, and exploratory investigation. J Marketing 62(2):92–109

Statista (2007) Kaufen Sie keine Produkte von einer Firma, von der Sie wissen, dass sie sich unsozial verhält (z.B. niedrige Löhne, Kinderarbeit oder Ähnliches)? http://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/178557/umfrage/boykott-unsozialer-firmen-kinderarbeit-schlechte-loehne-etc/. Accessed 25 April 2016

Steenhaut S, van Kenhove P (2006) The mediating role of anticipated guilt in consumers’ ethical decision-making. J Bus Ethics 69(3):269–288

Strack M, Gennerich C (2007) Erfahrung mit Forsyths’ Ethic Position Questionnaire? (EPQ): Bedeutungsunabhängigkeit von Idealismus und Realismus oder Akquieszens und Biplorarität? http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11780/418. Accessed 15 Oct 2016

Swaidan Z, Vitell SJ, Rawwas MYA (2003) Consumer ethics: determinants of ethical beliefs of African Americans. J Bus Ethics 46(2):175–186

Tangney JP, Stuewig J, Mashek DJ (2007) Moral emotions and moral behavior. Annu Rev Psychol 58:345–372

Tansey R, Brown G, Hyman MR, Dawson LE Jr (1994) Personal moral philosophies and the moral judgments of salespeople. J Pers Sell Sales Manag 14(1):59–75

TransFair (2015) Umsatz mit Fairtrade-Produkten in Deutschland in den Jahren 1993 bis 2014 (in Millionen Euro). http://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/226517/umfrage/fairtrade-umsatz-in-deutschland/. Accessed 25 November 2015

Van Kenhove P, Vermeir I, Verniers S (2001) An empirical investigation of the relationships between ethical beliefs, ethical ideology, political preference and need for closure. J Bus Ethics 32(4):347–361

Verhagen T, Nauta A, Feldberg F (2013) Negative online word-of-mouth: behavioral indicator or emotional release? Comput Hum Behav 29(4):1430–1440

Vitell SJ (2015) A case for consumer social responsibility (CnSR): including a selected review of consumer ethics/social responsibility research. J Bus Ethics 130(4):767–774

Vitell SJ, Paolillo JGP (2004) A cross-cultural study of the antecedents of the perceived role of ethics and social responsibility. Bus Ethics Eur Rev 13(2–3):185–199

Vitell SJ, Lumpkin JR, Rawwas MYA (1991) Consumer ethics: an investigation of the ethical beliefs of elderly consumers. J Bus Ethics 10(5):365–375

Wetzer I, Zeelenberg M, Pieters R (2007) Never eat in that restaurant, I did! Exploring why people engage in negative word-of-mouth communication. Psychol Mark 24(8):661–680

Wiener JL, Doescher TA (1991) A framework for promoting cooperation. J Mark 55(2):38–47

Williams JP (2009) The multidimensionality of resistance in youth-subcultural studies. Resist Stud Mag 1:20–33

Wilson MS (2003) Social dominance and ethical ideology: the end justifies the means. J Soc Psychol 143(5):549–558

Wojnicki AC, Godes D (2008) Word-of-mouth as self-enhancement. HBS Marketing Research Paper Nr. 06-01. doi:10.2139/ssrn.908999: Accessed 26 November 2015

Yuksel U, Mryteza V (2009) An evaluation of strategic responses to consumer boycotts. J Bus Res 62(2):248–259

Zerbe WJ, Paulhus DL (1987) Socially desirable responding in organizational behavior: a reconception. Acad Manag J 12(2):250–264

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1

Question items and factor loadings (in parentheses)

Idealism (VIF = 1.58/1.56/1.64) | |

ID_1 | The dignity and welfare of people should be the most important concern in any society. (0.78/0.77/0.83) |

ID_2 | One should never psychologically or physically harm another person. (0.78/0.78/0.75) |

ID_3 | If an action could harm an innocent other, then it should not be done. (0.82/0.82/0.77) |

ID_4 | One should not perform an action which might in any way threaten the dignity and welfare of another individual. (0.85/0.85/0.85) |

ID_5 | A person should make certain that their actions never intentionally harm another, even to a small degree. (0.83/0.82/0.81) |

Relativism (VIF = 1.20/1.23/1.23) | |

R_1 | Moral standards should be seen as being individualistic; what one person considers to be moral may be judged to be immoral by another person. (0.66/0.68/0.45) |

R_2 | Rigidly codifying an ethical position that prevents certain types of actions could stand in the way of better human relations and adjustment. (0.83/0.72/0.91) |

R_3 | Moral standards are simply personal rules which that indicate how a person should behave, and are not to be applied in making judgments of others. (0.68/0.89/0.63) |

R_4 | Questions of what is ethical for everyone can never be resolved since as what is moral or immoral is up to the individual. (0.86/0.80/0.80) |

Instrumental motives (VIF = 2.32/2.32/2.32) | |

By participating in this campaign… | |

I_1 | …I will help put pressure on the chocolate manufacturers to change their behavior. (0.85/0.85/0.85) |

I_2 | …I can help change the chocolate manufacturers’ behavior. (0.84/0.84/0.84) |

I_3 | My participation in this campaign is an effective means to make the chocolate manufacturers change their behavior. (0.86/0.86/0.86) |

I_4 | I am obliged to participate in this campaign against the chocolate industry because every contribution – no matter how small – is important for the plantation workers in Africa. (0.84/0.84/0.84) |

I_5 | I am obliged to use my freedom of choice and sovereignty as a consumer to help the plantation workers in Africa. (0.82/0.82/0.82) |

I_6 | I want to participate in a campaign against criticized chocolate manufacturers because I am keen on being part of a successful action. (0.86/0.86/0.86) |

Non-instrumental motives (VIF = 2.32/2.32/2.32) | |

By participating in this campaign, I could: | |

NI_1 | …express my anger toward the chocolate industry. (0.80/0.80/0.80) |

NI_2 | …vent my accumulated rage against the chocolate industry. (0.83/0.83/0.83) |

NI_3 | …reduce my anger toward the chocolate manufacturers. (0.78/0.78/0.78) |

NI_4 | …punish the chocolate manufacturers criticized. (0.79/0.79/0.79) |

NI_5 | …damage the chocolate manufacturers. (0.69/0.69/0.69) |

I would: | |

NI_6 | …feel guilty if I did not participate in the campaign against the chocolate industry. (0.79/0.79/0.79) |

NI_7 | …feel bad if other people who support the campaign saw me buying or eating products of the chocolate manufacturers criticized. (0.76/0.76/0.76) |

NI_8 | …feel good if I supported the campaign against the chocolate industry. (0.82/0.82/0.82) |

NI_9 | …feel good when participating because my friends/family are encouraging me to support the campaign against the chocolate industry. (0.76/0.76/0.76) |

Social dilemma-related costs (VIF = 1.43/1.43/1.43) | |

SD_1 | I do not need to participate in this campaign; enough other consumers are doing so/will do so. (0.85/0.85/0.85) |

SD_2 | I do not buy enough chocolate for it to be worthwhile participating; it would not even be noticed. (0.82/0.82/0.82) |

SD_3 | I would not participate in this campaign because it would put people in danger who make a living from their work on the plantations. (0.83/0.82/0.83) |

Product preference-related costs (VIF = 1.43/1.43/1.43) | |

I would not participate in this campaign because: | |

PP_1 | …fair trade chocolate is too expensive for me. (0.81/0.81/.81) |

PP_2 | …the selection of fairly produced confectionary is very limited. (0.89/0.89/0.89) |

PP_3 | …there is not enough fair trade cocoa available to meet the demand for chocolate in Germany. (0.86/0.86/.86) |

Boycott intention | |

I can well imagine: | |

B_1 | …completely avoiding chocolate from the manufacturers criticized during Christmas time. (0.83) |

B_2 | …substantially reducing the amount of chocolate I usually buy from the manufacturers criticized during Christmas time. (0.85) |

B_3 | …switching to fair trade chocolate, produced with fair trade cocoa, during Christmas time. (0.82) |

WOM intention | |

I can well imagine: | |

W_1 | …saying negative things about the chocolate manufacturers criticized to friends, relatives, and other people. (0.90) |

W_2 | …recommending that my friends, relatives, and other people do not buy products of the chocolate manufacturers criticized during Christmas time. (0.92) |

W_3 | …discrediting the chocolate manufacturers criticized with my friends, relatives, and other people. (0.89) |

Protest intention | |

I can well imagine: | |

P_1 | …directly complaining to the chocolate manufacturers criticized (e.g., via e-mail). (0.80) |

P_2 | …participating in actions of resistance on the internet against the chocolate manufacturers criticized (e.g., blogging or posting on social networks). (0.83) |

P_3 | …participating in “real actions” against the chocolate manufacturers criticized (e.g., demonstrations, flash mobs, distribution of flyers). (0.83) |

P_4 | …signing an online petition directed toward the chocolate manufacturers criticized, addressed to political decision makers in Berlin and Brussels. (0.73) |

P_5 | …sending money to an organization that devoted itself to fighting abusive labor conditions and child work on cocoa plantations in West Africa. (0.74) |

Appendix 2

Tests of hypotheses—PLS path analyses

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Andersch, H., Lindenmeier, J., Liberatore, F. et al. Resistance against corporate misconduct: an analysis of ethical ideologies’ direct and moderating effects on different forms of active rebellion. J Bus Econ 88, 695–730 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-017-0876-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-017-0876-2