Abstract

In this experimental study we analyze the trade-off between the subjects’ preference for wealth on the one hand and their preference for honesty on the other hand. The purpose of this research is to examine the effect of communication medium on reporting behavior. We want to know whether situational cues, such as the communication method—digital (via computer) vs. hard-copy (via paper and pencil) matter, while considering deception. Furthermore, we are interested in the relationship between the social value orientation (SVO) and the reporting behavior. While the experimental evidence shows that participants in both treatments have a preference for truthful reporting and they avoid major lies, there are also remarkable differences between the treatments which we attribute to the reporting medium: computer treatment CT versus paper-and-pencil treatment PPT. Agents are willing to report more honestly via a hard-copy medium than via a digital medium. It seems like participants perceive the digital report more confidential and anonymous than the hard-copy report, and that is why they tend to misrepresent in the CT rather than in the PPT. Further, we found that the SVO influences reporting behavior.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The values of X used in these two treatments are different. However, there are no systematical differences between them, because the same programmed random algorithm was used to forecast these values. We tested the difference between values of X used in the CT and in the PPT also statistically and found no significant differences.

The regression of integrity (i) on SVO gives similar results, in the CT even the same (because h = i) and in the PPT we find slightly higher difference between the integrity of cooperative and individualistic types: β = 0.226 and p < 0.02 (R 2 = 0.076).

References

Antle R, Eppen GD (1985) Capital rationing and organizational slack in capital budgeting. Manage Sci 31(2):415–444

Arnold MC (2007) Experimentelle forschung in der budgetierung—luegen, nichts als luegen? J fuer Betriebswirtschaft 57(2):69–99

Baiman S, Lewis BL (1989) An experiment testing the behavioral equivalence of strategically equivalent employment contracts. J Account Res 27(1):1–20

Bandura A (1991) Social cognitive theory of moral thought and action. In: Kurtines WM, Gewirtz L (eds) Handbook of moral behavior and development, vol 1. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, pp 45–103

Bandura A (1999) Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Pers Soc Psychol Rev (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates) 3(3):193

Bogaert S, Boone C, Declerck C (2008) Social value orientation and cooperation in social dilemmas: a review and conceptual model. Br J Soc Psychol 47(3):453–480

Brown JL, Evans JH III, Moser DV (2009) Agency theory and participative budgeting experiments. J Manag Account Res 21:317–345

Covaleski MA, Evans JH III, Luft JL, Shields MD (2007) Budgeting research: three theoretical perspectives and criteria for selective integration. Handb Manag Account Res 2:587–624

Daft RL, Lengel RH (1984) Information richness: a new approach to managerial behaviour and organizational design. Res Organ Behav 6:191–233

Daft RL, Lengel RH (1986) Organizational information requirements, media richness and structural design. Manage Sci 32(5):554–571

Daft RL, Lengel RH, Trevino LK (1987) Message equivocality, media selection, and manager performance: implications for information systems. MIS Q 11(3):354–366

DePaulo BM, Kashy DA, Kirkendol SE, Wyer MM, Epstein JA (1996) Lying in everyday life. J Pers Soc Psychol 70(5):979–995

Diekman A, Przepiorka W, Rauhut H (2011) Die Präventivwirkung des Nichtwissens im Experiment. Zeitschrift für Soziologie 40:74–84

Erat S, Gneezy U (2012) White lies. Manage Sci 58(4):723–733

Evans JH III, Hannan RL, Krishnan R, Moser DV (2001) Honesty in managerial reporting. Account Rev 76(4):537–559

Fandel G, Trockel J (2011a) A game theoretical analysis of an extended manager–auditor-conflict. Zeitschrift für Betriebswirtschaft 4:33–53

Fandel G, Trockel J (2011b) Optimal lot sizing in a non-cooperative material manager–controller game. Int J Prod Econ 133:256–261

Fandel G, Trockel J (2013) Avoiding non-optimal management decisions by applying a three-person inspection game. Eur J Oper Res 226:85–93

Fischbacher U (2007) z-Tree: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Exp Econ 10(2):171–178

Fischbacher U, Heusi F (2008) Lies in disguise—an experimental study on cheating. TWI Research Paper Series 40, Thurgau Institute of Economics

Gneezy U (2005) Deception: the role of consequences. Am Econ Rev 95(1):384–394

Hannan RL, Rankin FW, Towry KL (2006) The effect of information systems on honesty in managerial reporting: a behavioral perspective. Contemp Account Res 23(4):885–918

Koford K, Penno M (1992) Accounting, principal–agent theory, and self-interested behavior. In: Bowie NE, Freeman RE (eds) Ethics and agency theory, vol 1. Oxford University Press, New York, pp 127–142

Laffont J-J, Martimort D (2002) The theory of incentives: the Principal–Agent Model, vol 1. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Liebrand WBG (1984) The effect of social motives, communication and group size on behaviour in an n-person multi-stage mixed-motive game. Eur J Soc Psychol 14(3):239–264

Liebrand WBG, McClintock CG (1988) The ring measure of social values: a computerized procedure for assessing individual differences in information processing and social value orientation. Eur J Pers 2(3):217–230

Matuszewski LJ (2010) Honesty in managerial reporting: is it affected by perceptions of horizontal equity? J Manag Account Res 22:233–250

Mazar N, Amir O, Ariely D (2008) The dishonesty of honest people: a theory of self-concept maintenance. JMR 45(6):633–644

McClintock CG (1972) Social motivation—a set of propositions. Behav Sci 17(5):438–454

Meinert D, Vitell SJ, Blankenship R (1998) Respondent “honesty”: a comparison of computer versus paper and pencil questionnaire administration. J Mark Manag (10711988) 8(1):34–43

Mietek A, Leopold-Wildburger U (2011) Honesty in budgetary reporting—an experimental study. In: Klatte et al (eds) Operations research proceedings 2011, vol 1. Springer, Berlin, pp 205–210

Mittendorf B (2006) Capital budgeting when managers value both honesty and perquisites. J Manag Account Res 18:77–95

Naquin CE, Belkin LY, Kurtzberg TR (2010) The finer points of lying online: e-mail versus pen and paper. J Appl Psychol 95(2):387–394

Rankin FW, Schwartz ST, Young RA (2008) The effect of honesty and superior authority on budget proposals. Account Rev 83(4):1083–1099

Rasmußen A (2012) The influence of face-to-face communication. A principal–agent experiment. Cent Eur J Oper Res. doi: 10.1007/s10100-012-0270-7 (Online first)

Shalvi S, Handgraaf MJJ, De Dreu CKW (2011) Ethical manoeuvring: why people avoid both major and minor lies. Br J Manag 22:16–27

Sprinkle GB (2007) Perspectives on experimental research in managerial accounting. Handb Manag Account Res 1:415–444

Tourangeau R, Yan T (2007) Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychol Bull 133(5):859–883

Trockel J (2013) Changing bonuses and the resulting effects of employees’ incentives to an inspection game. J Bus Econ. doi:10.1007/s11573-013-0680-6

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for valuable hints by Reinhard Selten and two anonymous referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Instructions CT

Dear participants!

Thank you for your participation in this experiment. Please read carefully the instructions before starting the experiment! Your decisions during the experiment are connected with real payoffs. I.e. the more experimental Lira you earn in the experiment, the higher is your payoff in €. The exact conversion rate is: 1 experimental Lira = 0.20€.

The experiment consists of three parts: (1) the reporting experiment, (2) a short post-experimental questionnaire and (3) the preferences questionnaire.

1.1 The experimental task

The experiment reproduces the relationship between two parties within a company: the department manager (you) and the hypothetical shareholder (computer). You are the department manager of a company that has recently started a project that runs over five periods. You have been chosen as the main responsible person for the project.

It is common knowledge that the actual period’s production X ranges between 200 and 400 pieces, in steps of 20. You are however, due to your experience, able to forecast the actual period’s production for sure. You receive, at the beginning of each period, private perfect (100 % certain) information regarding the production. The level of production is random in each period.

Your task, each period, is to make a report regarding the production to the shareholder.

The following table includes your payoffs and payoffs of the shareholder for all possible X–B-combinations (your payoff/shareholders payoff) and it shell help you to determine your compensation:

Actual production X | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

200 | 220 | 240 | 260 | 280 | 300 | 320 | 340 | 360 | 380 | 400 | |

Report B | |||||||||||

200 | 50/60 | 56/65 | 62/70 | 68/75 | 74/80 | 80/85 | 86/90 | 92/95 | 98/100 | 104/105 | 110/110 |

220 | 48/58 | 54/63 | 60/68 | 66/73 | 72/78 | 78/83 | 84/88 | 90/93 | 96/98 | 102/103 | 108/108 |

240 | 46/56 | 52/61 | 58/66 | 64/71 | 70/76 | 76/81 | 82/86 | 88/91 | 94/96 | 100/101 | 106/106 |

260 | 44/54 | 50/59 | 56/64 | 62/69 | 68/74 | 74/79 | 80/84 | 86/89 | 92/94 | 98/99 | 104/104 |

280 | 42/52 | 48/57 | 54/62 | 60/67 | 66/72 | 72/77 | 78/82 | 84/87 | 90/92 | 96/97 | 102/102 |

300 | 40/50 | 46/55 | 52/60 | 58/65 | 64/70 | 70/75 | 76/80 | 82/85 | 88/90 | 94/95 | 100/100 |

320 | 38/48 | 44/53 | 50/58 | 56/63 | 62/68 | 68/73 | 74/78 | 80/83 | 86/88 | 92/93 | 98/98 |

340 | 36/46 | 42/51 | 48/56 | 54/61 | 60/66 | 66/71 | 72/76 | 78/81 | 84/86 | 90/91 | 96/96 |

360 | 34/44 | 40/49 | 46/54 | 52/59 | 58/64 | 64/69 | 70/74 | 76/79 | 82/84 | 88/89 | 94/94 |

380 | 32/42 | 38/47 | 44/52 | 50/57 | 56/62 | 62/67 | 68/72 | 74/77 | 80/82 | 86/87 | 92/92 |

400 | 30/40 | 36/45 | 42/50 | 48/55 | 54/60 | 60/65 | 66/70 | 72/75 | 78/80 | 84/85 | 90/90 |

After the last period one period-production level will be determined by chance and your payoff will be calculated accordingly your reporting decision in that particular period.

The shareholder will never find out, whether you have reported truthfully or not.

Try to put yourself into the situation and try to behave as if you were involved in a real decision making process.

Thank you for your participation!

Appendix 2: Instructions PPT

Dear participants!

Thank you for your participation in this experiment. Please read carefully the instructions before starting the experiment!

Your decisions during the experiment are connected with real payoffs. I.e. the more experimental Lira you earn in the experiment, the higher is your payoff in €.

The exact conversion rate is: 1 experimental Lira = 0.20€.

The experiment consists of three parts: (1) the reporting experiment, (2) a short post-experimental questionnaire and (3) a preferences questionnaire.

2.1 The experimental task

The experiment reproduces the relationship between two parties within a company: the department manager (you) and the hypothetical shareholder. You are the department manager of a company that has recently started a project that runs over five periods. You have been chosen as the main responsible person for the project.

It is common knowledge that the actual period’s production X ranges between 200 and 400 pieces, in steps of 20. You are however, due to your experience, able to forecast the actual period’s production for sure. You receive, at the beginning of each period, private perfect (100 % certain) information regarding the production. The level of production is random in each period.

Your task, each period, is to make a report regarding the production to the shareholder.

The following table includes your payoffs and payoffs of the shareholder for all possible X–B-combinations (your payoff/shareholder’s payoff) and it shell help you to determine your compensation:

Actual production X | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

200 | 220 | 240 | 260 | 280 | 300 | 320 | 340 | 360 | 380 | 400 | |

Report B | |||||||||||

200 | 50/60 | 56/65 | 62/70 | 68/75 | 74/80 | 80/85 | 86/90 | 92/95 | 98/100 | 104/105 | 110/110 |

220 | 48/58 | 54/63 | 60/68 | 66/73 | 72/78 | 78/83 | 84/88 | 90/93 | 96/98 | 102/103 | 108/108 |

240 | 46/56 | 52/61 | 58/66 | 64/71 | 70/76 | 76/81 | 82/86 | 88/91 | 94/96 | 100/101 | 106/106 |

260 | 44/54 | 50/59 | 56/64 | 62/69 | 68/74 | 74/79 | 80/84 | 86/89 | 92/94 | 98/99 | 104/104 |

280 | 42/52 | 48/57 | 54/62 | 60/67 | 66/72 | 72/77 | 78/82 | 84/87 | 90/92 | 96/97 | 102/102 |

300 | 40/50 | 46/55 | 52/60 | 58/65 | 64/70 | 70/75 | 76/80 | 82/85 | 88/90 | 94/95 | 100/100 |

320 | 38/48 | 44/53 | 50/58 | 56/63 | 62/68 | 68/73 | 74/78 | 80/83 | 86/88 | 92/93 | 98/98 |

340 | 36/46 | 42/51 | 48/56 | 54/61 | 60/66 | 66/71 | 72/76 | 78/81 | 84/86 | 90/91 | 96/96 |

360 | 34/44 | 40/49 | 46/54 | 52/59 | 58/64 | 64/69 | 70/74 | 76/79 | 82/84 | 88/89 | 94/94 |

380 | 32/42 | 38/47 | 44/52 | 50/57 | 56/62 | 62/67 | 68/72 | 74/77 | 80/82 | 86/87 | 92/92 |

400 | 30/40 | 36/45 | 42/50 | 48/55 | 54/60 | 60/65 | 66/70 | 72/75 | 78/80 | 84/85 | 90/90 |

After the last period one period-production level will be determined by chance and your payoff will be calculated accordingly your reporting decision in that particular period.

After you have read the instructions take the large envelope containing:

-

a set of report forms sequentially ordered (beginning with period 1) (yellow sheet of paper with the appropriate period number),

-

very short post-experimental questionnaire (blue form) and

-

preferences questionnaire (red form).

Each report form provides the perfect (100 % certain) information regarding the period’s production and also the payoff-table. At the beginning of each period:

-

1.

take one report form from the envelope,

-

2.

put your confidential participant number on it,

-

3.

after seeing the perfect information of the production consult the payoff-table make your report decision and

-

4.

proceed to the next period.

The shareholder will never find out, whether you have reported truthfully or not.

Try to put yourself into the situation and try to behave as if you were involved in a real decision making process.

After the last experimental period fill in all questionnaires ((1) the post-experimental questionnaire and (2) the preferences questionnaire). Please put your confidential participant number on each form in the field “your confidential participant number”.

Thank you for your participation!

Appendix 3: Post-experimental questionnaire

See Table 6.

Appendix 4: Ring measure of social values

Appendix 5: CT—experimental task

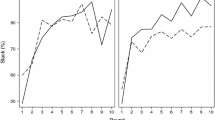

See Fig. 6.

Appendix 6: Report Form PPT

Actual production X | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

200 | 220 | 240 | 260 | 280 | 300 | 320 | 340 | 360 | 380 | 400 | |

Report B | |||||||||||

200 | 50/60 | 56/65 | 62/70 | 68/75 | 74/80 | 80/85 | 86/90 | 92/95 | 98/100 | 104/105 | 110/110 |

220 | 48/58 | 54/63 | 60/68 | 66/73 | 72/78 | 78/83 | 84/88 | 90/93 | 96/98 | 102/103 | 108/108 |

240 | 46/56 | 52/61 | 58/66 | 64/71 | 70/76 | 76/81 | 82/86 | 88/91 | 94/96 | 100/101 | 106/106 |

260 | 44/54 | 50/59 | 56/64 | 62/69 | 68/74 | 74/79 | 80/84 | 86/89 | 92/94 | 98/99 | 104/104 |

280 | 42/52 | 48/57 | 54/62 | 60/67 | 66/72 | 72/77 | 78/82 | 84/87 | 90/92 | 96/97 | 102/102 |

300 | 40/50 | 46/55 | 52/60 | 58/65 | 64/70 | 70/75 | 76/80 | 82/85 | 88/90 | 94/95 | 100/100 |

320 | 38/48 | 44/53 | 50/58 | 56/63 | 62/68 | 68/73 | 74/78 | 80/83 | 86/88 | 92/93 | 98/98 |

340 | 36/46 | 42/51 | 48/56 | 54/61 | 60/66 | 66/71 | 72/76 | 78/81 | 84/86 | 90/91 | 96/96 |

360 | 34/44 | 40/49 | 46/54 | 52/59 | 58/64 | 64/69 | 70/74 | 76/79 | 82/84 | 88/89 | 94/94 |

380 | 32/42 | 38/47 | 44/52 | 50/57 | 56/62 | 62/67 | 68/72 | 74/77 | 80/82 | 86/87 | 92/92 |

400 | 30/40 | 36/45 | 42/50 | 48/55 | 54/60 | 60/65 | 66/70 | 72/75 | 78/80 | 84/85 | 90/90 |

Appendix 7: Statistics: Post-experimental Questionnaire

See Table 7.

Appendix 8: Honesty measures

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rasmußen, A., Leopold-Wildburger, U. Honesty in intra-organizational reporting. J Bus Econ 84, 929–958 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-014-0740-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11573-014-0740-6