Abstract

Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) present developing countries with a trade-off. BITs plausibly increase access to international capital in the form of foreign direct investment (FDI), but at the cost of substantially curtailing a government’s policy autonomy. Nearly 3000 BITs have been entered into, suggesting that many countries have found this trade-off acceptable. But governments’ enthusiasm for signing and ratifying BITs has varied considerably across countries and across time. Why are BITs more popular in some places and times than others? We argue that capital scarcity is an important driver of BIT signings: The trade-off inherent in BITs becomes more attractive to governments as the need to secure access to international capital increases. More specifically, we argue that the coincidence of high US interest rates and net external financial liabilities heightens governments’ incentives to secure access to foreign capital, and therefore results in BIT signings. Empirical evidence is consistent with our theory.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Forbes 3/5/2014. Why The Worst Is Still Ahead For Turkey’s Bubble Economy.

Die Zeit, January 2014.

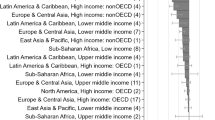

As in all of the following, we exclude OECD countries from the sample as a means of limiting our analysis to primarily capital importing countries. (Another rationale for excluding high-income countries, with more stable and mature economies, is that they should be less affected by changes in US monetary policies; see also Di Giovanni and Shambaugh 2008.) Except for the initial OECD members, a country is included in the sample up to the point when it joined the OECD. The equation of OECD membership with “capital exporting” is, of course, inexact. And while this coding rule benefits from conceptual parsimony, some countries – Turkey for most of the 20th century, for example – are likely mislabeled by it. In practice, this rule does not seem to matter much to the reported regressions: We did not find substantially different results when using alternative proxies for capital exporting. The regressions in Table 1 include a linear year trend and a control for the gross domestic product (GDP) (measured in billions of $US). We obtain similar results when including country fixed effects, or when including a lagged dependent variable. We also obtain similar (and slightly stronger) results if we substitute the three-year moving average of the US interest rate as the key independent variable.

Notably, the negative relationship between interest rates and FDI inflows speaks only to the financial aspects of FDI, and does not necessarily imply that such a relationship exists with regards to commercial aspects of FDI (Kerner 2014).

More recently – and exotically – in early 2014 the Argentinean government announced a 50 percent tax on purchases over US $25 made by Argentinean customers on international websites, and it limited such transactions to at most two such purchases a year. These measures were, as observers noted, a deliberate “attempt to shore-up dipping reserves of foreign currency” (Garcia-Navarro, National Public Radio, 2014) and “to curb capital flight and prevent a possible balance-of-payments crisis” (Gilbert and Rathbone, Financial Times, 2014).

The ability to maintain interest rates at below world levels also allows governments to finance themselves domestically at cheaper rates, which is particularly valuable when foreign debt-loads are significant (Aizenman and Guidotti 1990).

It is also possible that creditors and credit rating agencies may favor countries that make durable, treaty-based commitments to the liberal economic order (Biglaiser and DeRouen 2007). BITs may provide an opportunity for countries to send such a signal (Büthe and Milner 2009; Kerner 2009) and may thereby ease access to other investment flows as well. While possible, Poulsen (2014) suggests good reason for skepticism in this regard.

It is important to point out explicitly that even the most fervent believer in BITs’ efficacy is unlikely to believe that the potential increases in capital inflows and export receipts would in themselves provide a solution to (potential or real) balance of payments issues. But to the extent that BITs do attract FDI, expand exports, or function as signals to creditors, they can very plausibly provide marginal help to countries during times of capital scarcity. To the extent that BITs do play such a role they almost certainly do so as a minor part in a larger set of liberal and illiberal policy initiatives meant to maintain access to hard currency. Our argument is simply that the intrinsic trade-off between the possibility of gaining access to foreign capital in exchange for policy autonomy will appear more palatable to governments at times when that capital is especially needed.

While some of the larger emerging markets have lessened the extent of their original sin in recent years, it remains a substantial problem even in the most developed of emerging market economies (e.g., Kynge 2015). This dynamic is reinforced by the fact that emerging markets typically borrow in short-term maturities (Broner et al. 2013).

Notably, this eliminates south-south BITs from our analysis.

The negative binomial model is a generalization of the Poisson model that allows for overdispersion in the data (Cameron and Trivedi 2005).

Nearly identical results when clustering standard errors by country or estimating these models with unclustered standard errors.

These results are also robust to controlling for the domestic interest rate.

See Betz (2014) for a different perspective on partisan hands-tying.

See Allison and Waterman (2002) for a discussion of fixed effects in negative binomial models.

These calculations omit China, which has substantially larger net assets than any other country in the sample. Including or omitting China from the sample does not matter for the substantive conclusions presented in the following, however.

It should be noted, however, that while our models provide evidence to suggest the existence of a range of low interest rates for which the effect of an increase in net foreign assets is to increase BIT signings and a range of high interest rates for which the effect of an increase in net foreign assets is to decrease BIT signings, our results give a substantially less consistent picture of how large those ranges are. The average effect, in any event, tends to be not statistically significant at conventional levels.

For better readability, the left panel of Fig. 1 omits the largest and smallest one percent of net foreign assets.

Several low-income countries had, at times, an interest rate of zero on newly issued government debt. Many of these countries obtained interest-rate free loans from the World Bank’s International Development Association. The following results are robust to omitting these countries from the sample.

A duration model has a number of advantages in the present context. Most importantly, we can include time-varying variables, such as US interest rates, in a straightforward manner (whereas with a standard linear regression model, we would have to use period-averages or another arbitrary value within the time period for such variables).

We include in our specification controls for GDP, GDP growth, the US inflation rate, and the US growth rate. The findings are robust to the inclusion of many other controls, including FDI and Trade as percentages of GDP, GDP per capita and others. These findings are also robust to excluding all controls.

References

Aizenman, J., & Guidotti, P. E. (1990). Capital Controls, Collection Costs, and Domestic Public Debt. Cambridge, MA: NBER Working Paper No. 3443.

Alesina, A., Grilli, V., Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (1993). The Political Economy of Capital Controls. NBER Working Paper No. 4353.

Allee, T., & Peinhardt, C. (2010). Delegating differences: bilateral investment treaties and bargaining over dispute resolution provisions. International Studies Quarterly, 54(1), 1–26.

Allison, P. D., & Waterman R. P. (2002). Fixed-effects negative binomial regression models. Sociological methodology, 32(1), 247–265.

Beck, T., Clarke, G., Groff, A., Keefer, P., & Walsh, P. (2001). New tools in comparative political economy: the database of political institutions. World Bank Economic Review, 15(1), 165–176.

Betz, T. (2014). Institutional Commitments and Electoral Incentives. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Working Paper.

Betz, T., & Kerner, A. (2014). Liberal mercantilism: exchange rate regimes, foreign currency denominated debt and trade disputes. Political economy of international organizations conference. Princeton: Political Economy of International Organizations Conference.

Biglaiser, G., & DeRouen, K. J. (2007). Sovereign bond ratings and neoliberalism in Latin America. International Studies Quarterly, 51(1), 121–138.

Blackstone, B., Stamouli, N., & Forelle, C. (2015). Greece Orders Banks Closed, Imposes Capital Controls to Stem Deposit Flight. The Wall Street Journal, June 28, 2015.

Block, F. L. (1977). The origins of international economic disorder. A study of united states international monetary policy from world war II to the present. BerkeleyCA: University of California Press.

Broner, F. A., Lorenzoni, G., & Schmukler, S. L. (2013). Why do emerging economies borrow short term? Journal of the European Economic Association, 11(1), 67–100.

Brooks, S. M., & Kurtz, M. J. (2007). Capital, trade, and the political economies of reform. American Journal of Political Science, 51(4), 703–720.

Büthe, T., & Milner, H. V. (2009). The effect of treaties on foreign direct investment: bilateral investment treaties, double taxation treaties, and investment flows: Bilateral investment treaties and foreign direct investment: a political analysis. Oxford: University Press.

Calvo, G., Leiderman, L., & Reinhart, C. (1993). Capital inflows and real exchange rate appreciation in Latin America: the role of external factors. IMF Staff Papers, 40(1), 108–150.

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics. Methods and applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chen, Z., & Khan, M. (1997). Patterns of Capital Flows to Emerging Markets: A Theoretical Perspective. Washington, DC: IMF Working Paper No. 97/13.

Clark, W. R. (2002). Partisan and electoral motivations and the choice of monetary institutions under fully mobile capital. International Organization, 56(4), 725–749.

Clark, W. R., & Arel-Bundock, V. (2013). Independent but not indifferent: Partisan bias in monetary policy at the Fed. Economics and Politics, 25(1), 1–26.

Di Giovanni, J., & Shambaugh, J. (2008). The impact of foreign interest rates on the economy: the role of the exchange rate regime. Journal of International Economics, 74(2), 341–361.

Diaz-Alejandro, C. F. (1984). Latin American debt: I don’t think we are in Kansas anymore. Brookings papers on economic activity, 335–403.

Eichengreen, B. (2008). Globalizing capital. A history of the international monetary system. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Eichengreen, B., Hausmann, R., & Panizza, U. (2005). The pain of original sin. In B. Eichengreen & R. Hausmann (Eds.), Other people’s money: Debt denomination and financial instability in emerging market economies (pp. 13–47). Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Elkins, Z., Guzman, A. T., & Simmons, B. A. (2006). Competing for capital: the diffusion of bilateral investment treaties, 1960–2000. International Organization, 60(04), 811–846.

Finger, J. M., & Hardy, R. (1995). Legalized backsliding: safeguard provisions in GATT. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Frankel, J., & Roubini, N. (2001). The Role of Industrial Country Policies in Emerging Market Crises. NBER Working Paper No. 8634.

Gaillard, E. (2008). Anti-arbitration trends in Latin America. The New York Law Journal, 239, 108.

Gallagher, K. P., & Birch, M. B. L. (2006). Do investment agreements attract investment? Evidence from Latin America. Journal of World Investment and Trade, 7(6), 961–973.

Ginsburg, T. (2005). International substitutes for domestic institutions: bilateral investment treaties and governance. International Review of Law and Economics, 25(1), 107–123.

Goldstein, J. O., Kahler, M., Keohane, R. O., & Slaughter, A.-M. (2000). Introduction: legalization and world politics. International Organization, 54(3), 385–399.

Gomez, K. F. (2011). Latin America and ICSID: David versus Goliath. Law and Business Review of the Americas, 17, 195.

Haftel, Y. Z., & Thompson, A. (2013). Delayed ratification: the domestic fate of bilateral investment treaties. International Organization, 67(2), 355–387.

Hausmann, R., & Panizza, U. (2003). On the determinants of Original Sin: an empirical investigation. Journal of International Money and Finance, 22(7), 957–990.

Irwin, D. A. (2013). The Nixon shock after forty years: the import surcharge revisited. World Trade Review, 12(1), 29–56.

Jandhyala, S., Henisz, W. J., & Mansfield, E. D. (2011). Three waves of BITs: the global diffusion of foreign investment policy. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 55(6), 1047–1073.

Kerner, A. (2009). Why should I believe you? The costs and consequences of bilateral investment treaties. International Studies Quarterly, 53(1), 73–102.

Kerner, A. (2014). What we talk about when we talk about foreign direct investment. International Studies Quarterly, 58(4), 804–815.

Kerner, A., & Lawrence, J. (2013). “What’s the Risk? Bilateral Investment Treaties, Political Risk and Fixed Capital.” British Journal of Political Science 44(1): 107–21.

Kynge, J. (2015). Original sin stalks vulnerable EMs as US dollar surges. Financial Times, February 11, 2015.

Lane, P., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2001). The external wealth of nations: measures of foreign assets and liabilities for industrial and developing countries. Journal of International Economics, 55(2), 263–294.

Lane, P., & Milesi-Ferretti, G. M. (2007). The external wealth of nations mark II: revised and extended estimates of foreign assets and liabilities, 1970–2004. Journal of International Economics, 73(2), 223–250.

Lane, P., & Shambaugh, J. (2010). Financial exchange rates and international currency exposures. American Economic Review, 100(1), 518–40.

Neumayer, E. (2001). Do countries fail to raise environmental standards? An evaluation of policy options addressing“ regulatory chill”. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 4(3), 231–244.

Neumayer, E., & Spess, L. (2005). Do bilateral investment treaties increase foreign direct investment to developing countries? World development, 33(10), 1567–1585.

Poulsen, L. N. S. (2014). Bounded rationality and the diffusion of modern investment treaties. International Studies Quarterly, 58(1), 1–14.

Poulsen, L. N. S., & Aisbett, E. (2013). When the claim hits: bilateral investment treaties and bounded rational learning. World Politics, 65(2), 273–313.

Quinn, D. P., & Inclan, C. (1997). The origins of financial openness: a study of current and capital account liberalization. American Journal of Political Science, 41(3), 771–813.

Roberts, R. (2013). ‘Unwept, unhonoured and unsung’: Britain’s import surcharge, 1964–1966, and currency crisis management. Financial History Review, 20(2), 209–229.

Rosendorff, B. P., & Shin, K. (2012). Importing Transparency: The Political Economy of BITs and FDI Flows. Manuscript, New York University Political Science Department. New York, NY: NYU. Available at: https://files.nyu.edu/bpr1/public/papers/RosendorffShinAPSA2012.pdf.

Rosendorff, B. P., & Kongjoo, S. (2014). Regime Type and International Commercial Agreements. Unpublished, New York University.

Simmons, B. A. (2014). Bargaining over BITs, arbitrating awards: the regime for protection and promotion of international investment. World Politics, 66(1), 12–46.

Tevendale, C., & Nalsh, V. (2014). Indonesia indicates intention to terminate all of its bilateral investment treaties? March 20, 2014. Herbert Smith Freehills LLP.

Tobin, J. L., & Rose-Ackerman S. (2011). When BITs have some bite: The political-economic environment for bilateral investment treaties. The Review of International Organizations, 6(1), 1–32.

UNCTAD. (2014). World investment report. New York: United Nations.

Vaubel, R. (1997). The bureaucratic and partisan behavior of independent central banks: German and international evidence. European Journal of Political Economy, 13(2), 201–224.

Walter, S. (2008). “A New Approach for Determining Exchange-Rate Level Preferences.” International Organization 62(3): 405–38.

Wei, Y., & Liu, X. (2006). Productivity spillovers from R&D, exports and FDI in China’s manufacturing sector. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(4), 544–557.

Yackee, J. W. (2007) Do BITs really work? Revisiting the empirical link between investment treaties and foreign direct investment (October 2007). Univ. of Wisconsin Legal Studies Research Paper No. 1054. doi:10.2139/ssrn.1015083.

Yackee, J. W. (2010). Do Bilateral Investment Treaties Promote Foreign Direct Investment-Some Hints from Alternative Evidence. Virginia Journal of International Law, 51, 397.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(ZIP 1258 kb)

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Betz, T., Kerner, A. The influence of interest: Real US interest rates and bilateral investment treaties. Rev Int Organ 11, 419–448 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-015-9236-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-015-9236-6