Abstract

The concept of a regime complex has proved fruitful to a burgeoning literature in international relations, but it has also opened up new questions about how and why they develop over time. This article describes the history of the energy regime complex as it has changed over the past 40 years, and interprets this history in light of an interpretive framework of the sources of institutional change. One of its principal contributions is to highlight what Stephen Krasner referred to as a pattern of “punctuated equilibrium” reflecting both periods of stasis and periods of innovation, as opposed to a gradual process of change. We show that the timing of innovation depends on dissatisfaction and shocks and that the nature of innovation—that is, whether it is path-dependent or de novo—depends on interest homogeneity among major actors. This paper is the first to demonstrate the empirical applicability of the punctuated equilibrium concept to international regime complexes, and contributes to the eventual development of a dynamic theory of change in regime complexes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This definition is intentionally imprecise. We caution against an overly precise definition of the reference level for satisfaction, as it is necessarily shaped by context and circumstances.

It is also possible that an institution could be created when there is no relevant existing institution at all, but given the large number and breadth of international organizations, we expect this to be very rare.

We are indebted to an anonymous reviewer for pointing this out.

There is also an APEC-Energy Working Group to foster energy dialogue in the Asia-Pacific region, but it is not a formal, independent organization.

See, for example, President Eisenhower’s Atoms for Peace speech. Available from: http://www.iaea.org/About/history_speech.html. Accessed 11 March 2010.

An interesting exception is the European Coal Organization (ECO), founded in 1945 to allocate available coal supplies to needy member states. Although the ECO was regarded as quite effective, it was disbanded in 1947 by a unanimous decision of its member states.

The measures were carried over from the OECD’s predecessor, the Organization for European Economic Cooperation.

The Soviet Union and its allies were outside this system, being essentially self-sufficient in oil.

OPEC Annual Statistical Bulletin, available through http://www.opec.org. The following countries joined OPEC in the 1960s–1970s: Qatar (1961), Indonesia (1962), Libya (1962), the United Arab Emirates (1967), Algeria (1969), Nigeria (1971), Ecuador (1973), and Gabon (1975).

Anno 2011, only six OECD countries have not joined the IEA, either because they do not want to—as is the case with Iceland and Mexico—or because they have only recently joined the OECD—as is the case with Chile, Estonia, Slovenia and Israel, which have all joined the OECD in the course of 2010.

In 2010, the five divisions were known as: the Executive Office, Oil Markets and Emergency Preparedness, Energy Technology and R&D, Long-term Cooperation and Policy Analysis, and the Global Energy Dialogue.

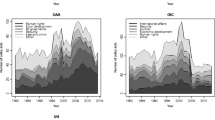

Poland and Slovakia, which did not join the IEA until 2008, are omitted from this figure.

Interview with William C. Ramsay, former deputy director of the International Energy Agency, Brussels, May 6, 2010.

Interview with Claude Mandil, former Executive Director of the IEA, Paris, 9 March 2010.

Source: http://www.encharter.org/index.php?id=21&id_article=205&L=0. Accessed 6 May 2009.

The G7 has always been principally a set of oil-importing states, although this balance was shifted somewhat when it became the G8, including Russia. We focus on G7 activity as a measure of dissatisfaction by oil-importing states.

Declaration available from: http://www.ren21.net/pdf/Political_declaration_final.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2010.

See: www.irena.org. Accessed 6 May 2010. A complementary explanation for the timing of change in the energy regime complex involves the increasing salience of climate change, but in view of the facts that (i) there has been little progress on effective climate change agreements, and (ii) institutional changes in the oil/energy regime complex did not appear until oil prices rose sharply, concern about climate change does not seem to provide a plausible alternative explanation of recent institutional innovation.

Interview with German official, Berlin, 6 November 2008.

Interview with William C. Ramsay, former deputy director of the International Energy Agency, May 6, 2010.

We are indebted to our two referees, each of whom raised one of these questions.

References

Aggarwal, V. K. (1998). Institutional Designs for a Complex World: Bargaining, Linkages, and Nesting. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Alter, K., & Meunier, S. (2009). The Politics of International Regime Complexity. Perspectives on Politics, 7(1), 13–24.

Anderson, I. H. (1981). Aramco, the United States and Saudi Arabia: A Study of the Dynamics of Foreign Oil Policy, 1933–1950. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bamberger, C. S. (2004). History of the IEA: The First 30 Years. Paris: OECD/IEA.

Bates, R. H., et al. (1998). Analytic Narratives. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Biermann, F., Pattberg, P., van Asselt, H., & Zelli, F. (2009). The Fragmentation of Global Governance Architectures: A Framework for Analysis. Global Environmental Politics, 9(4), 14–40.

Bohi, D. R., & Russell, M. (1978). Limiting Oil Imports: an Economic History and Analysis. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press for Resources for the Future.

Claes, D.-H. (2001). The Politics of Oil-Producer Cooperation. Oxford: Westview Press.

Colgan, J. D. (2009). The International Energy Agency—Challenges for 2010 and Beyond. GPPi Policy Paper #6. Berlin: Global Public Policy Institute.

Colgan, J. D. (2010). The Landscape of International Energy Institutions. Working paper of the S.T. Lee Project on Global Energy Governance, National University of Singapore

Diehl, P. F., & Ku, C. (2010). The Dynamics of International Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Eckstein, H. (1975). Case Studies and Theory in Political Science. In F. I. Greenstein & N. W. Polsby (Eds.), Handbook of Political Science (pp. 79–137). Reading Mass: Addison-Wesley.

El-Gamal, M. A., & Jaffe, A. M. (2010). Oil, Dollars, Debt, and Crises: The Global Curse of Black Gold. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Eurosolar and World Council for Renewable Energy (WCRE). (2009). The Long Road to IRENA: From the Idea to the Foundation of the International Renewable Energy Agency. Bochum: Bonte Press. Available from: http://www.eurosolar.de/en/images/stories/pdf/IRENA_Long_Road_Book.pdf. Accessed 6 May 2010.

Florini, A., & Sovacool, B. (2011). Bridging the Gaps in Global Energy Governance. Global Governance, 17(1), 57–74.

Fox, W. (1996). The United States and the Energy Charter Treaty: Misgivings and Misperceptions. In T. Wälde (Ed.), The Energy Charter Treaty: An East-West Gateway for Investment & Trade (pp. 194–201). London: Kluwer.

Goertz, G. (2003). International Norms and Decision-Making: A Punctuated Equilibrium Model. Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield.

Goldthau, A., & Witte, J. M. (2010). Global Energy Governance: The New Rules of the Game. Washington: Brookings Institution Press.

Helfer, L. R. (2004). Regime Shifting: The TRIPs Agreement and New Dynamics of International Intellectual Property Lawmaking. Yale Journal of International Law, 29(1), 1–83.

Ikenberry, G. J. (1988). Market Solutions for State Problems: The International and Domestic Politics of American Oil Decontrol. International Organization, 42(1), 151–177.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2007.) The next 10 years are critical—the world energy outlook makes the case for stepping up co-operation with China and India to address global energy challenges. Press release 07(22). http://www.iea.org/textbase/press/pressdetail.asp?PRESS_REL_ID=239. Accessed 6 May 2010.

Katz, J. E. (1981). The International Energy Agency: Processes and Prospects in an Age of Energy Interdependence. Studies in Comparative International Development, 16(2), 67–85.

Keohane, R. O. (1982). The Demand for International Regimes. International Organization, 36(2), 325–355.

Keohane, R. O. (1984). After Hegemony: Cooperation and Discord in the World Political Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (1977/2001). Power and Interdependence. New York: Longman.

Keohane, R. O., & Nye, J. S. (2000). Introduction. In J. S. Nye & J. D. Donahue (Eds.), Governance in a Globalizing World (pp. 1–42). Washington: Brookings Institution.

Keohane, R. O., & Victor, D. (2011). The Regime Complex for Climate Change. Perspectives on Politics, 9(1), 7–23.

Kingdon, J. W. (1984). Agendas, alternatives, and public policy. Boston: Little, Brown.

Krasner, S. D. (1984). Approaches to the State: Alternative Conceptions and Historical Dynamics. Comparative Politics, 16(2), 223–246.

Lesage, D., Van de Graaf, T., & Westphal, K. (2010). Global Energy Governance in a Multipolar World. Farnham: Ashgate Publishing.

Morse, E. L. (1999). A New Political Economy of Oil? Journal of International Affairs, 53(1), 1–29.

Odell, J. S. (2001). Case Study Methods in International Political Economy. International Studies Perspectives, 2(2), 161–76.

Parra, F. (2010). Oil Politics: A Modern History of Petroleum. London: I.B. Tauris.

Pierson, P. (2004). Politics in Time: History, Institutions, and Social Analysis. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Raustiala, K., & Victor, D. (2004). The Regime Complex for Plant Genetic Resources. International Organization, 58(2), 277–309.

Scheer, H. (2007). Energy Autonomy: The Economic, Social and Technological Case for Renewable Energy. London: Earthscan.

Scott, R. (1977). Innovation in International Organization: The International Energy Agency. Hastings International and Comparative Law Review, 1(1), 1–56.

Shanks, C., Jacobson, H. K., & Kaplan, J. (1996). Inertia and Change in the Constellation of International Governmental Organizations, 1981–1992. International Organization, 50(4), 593–627.

Simon, H. A. (1982). Models of Bounded Rationality, 2 volumes. Cambridge: MIT.

Smil, V. (2005). Energy at the Crossroads: Global Perspectives and Uncertainties. Cambridge: The MIT.

Steinberg, R. H. (2002). In the Shadow of Law or Power? Consensus-Based Bargaining and Outcomes in the GATT/WTO. International Organization, 56(2), 339–374.

Thompson, A. (2010). Rational Design In Motion: Uncertainty and Flexibility in the Global Climate Regime. European Journal of International Relations, 16(2), 269–296.

Van de Graaf, T., & Lesage, D. (2009). The International Energy Agency after 35 Years: Reform Needs and Institutional Adaptability. The Review of International Organizations, 4(3), 293–317.

Victor, D., & Yueh, L. (2010). The New Energy Order: Managing Insecurities in the Twenty-first Century. Foreign Affairs, 89(1), 61–73.

Victor, D., Joy, S., & Victor, N. M. (2006). The Global Energy Regime. Unpublished manuscript (on file with authors).

Yergin, D. (1991). The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money and Power. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Young, O. R. (2002). The Institutional Dimensions of Environmental Change: Fit, Interplay, and Scale. Cambridge: MIT.

Young, O. R. (2010). Institutional Dynamics: Emergent Patterns in International Environmental Governance. Cambridge: MIT.

Acknowledgement

First of all, we thank Lauren Bleakney for excellent research assistance on the revision of this paper, which included not only collecting information and making calculations, but also making very perceptive critical points about the manuscript that led directly to improvements. For comments on early drafts of this paper, we thank Joseph Nye, Peter Katzenstein, and participants of the Princeton IR Graduate Seminar, the 4th Annual Conference on The Political Economy of International Organizations, January 27-29, 2011, Zurich, and the 2nd ULB-UGent Workshop on International Relations, May 27-28, Brussels. We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers of the RIO for their very perceptive and helpful comments. Two of the authors (Colgan and Van de Graaf) have benefited from participation in the S.T. Lee Project on Global Governance led by Ann Florini at the National University of Singapore. We thank the organizers and participants, who have contributed to our thinking about this paper. Jeff Colgan gratefully acknowledges financial support from The Lynde and Harry Bradley Foundation; Robert O. Keohane acknowledges generous research support from Princeton University; and Thijs Van de Graaf acknowledges the Flemish Research Foundation (FWO) for a PhD fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Colgan, J.D., Keohane, R.O. & Van de Graaf, T. Punctuated equilibrium in the energy regime complex. Rev Int Organ 7, 117–143 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-011-9130-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-011-9130-9

Keywords

- Regime complex

- Energy

- Institutional innovation

- Institutional design

- Oil

- Punctuated equilibrium

- Path dependence