Abstract

Background

Opioids are routinely prescribed after hand surgery, but there is limited research about surgeon variation in prescription patterns and attitudes toward the use of these drugs. We sought to examine hand surgeons’ attitudes, beliefs, and self-reported practices regarding the use of opioids.

Methods

An invitation to an online cross-sectional survey was sent to 3225 hand surgeons across the USA via email, of whom 502 (16 %) responded. We used previously published data to compare hand surgeons’ concerns about potential adverse opioid-related events with those of primary care physicians.

Results

Most hand surgeons (76 %) reported prescription opioid abuse to be a big or moderate problem in their communities, and 89 % felt that opioids are overused to treat pain. Nearly all (94 %) were very or moderately confident about their clinical skills regarding opioid prescribing, but only 40 % reported always or often asking about a history of opioid abuse or dependence before scheduling surgery. Most (75 %) were very or moderately comfortable refilling opioid prescriptions following fracture surgery, while only 13 % were comfortable doing so after minor elective surgery. Nearly half (49 %) reported being less likely to prescribe opioids compared to 1 year ago, and 67 % believed that the best approach to reduce postoperative opioid use is to discuss pain management and expectations with the patient before surgery. Compared to primary care physicians, hand surgeons were less likely to be concerned about potential adverse patient (e.g., opioid-related addiction [67 vs. 84 %], death [37 vs. 70 %], sedation [57 vs. 71 %]) and prescriber (e.g., malpractice claim [22 vs. 46 %], prosecution [15 vs. 45 %], censure by state medical boards [16 vs. 44 %]) outcomes.

Conclusion

Hand surgeons have become aware of the extent and public health implications of the prescription opioid epidemic, and many are taking an active role by reducing their reliance on these drugs. Additional research using pharmacy data is needed to confirm the extent to which hand surgeons’ reliance on prescription opioids is actually decreasing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The USA is in the midst of a prescription opioid overdose and abuse epidemic [9]. Physicians were advised to use more and stronger opioids for pain relief, prescriptions for opioid analgesics rose [21, 29], and now, prescription opioids constitute the most common cause of unintentional overdose, lead to more deaths annually than all illicit drugs combined [15], and have created a resurgence in heroin use [17, 33]. Opioids are often prescribed for management of nonmalignant musculoskeletal pain [2, 5, 6, 12, 19, 34], in spite of uncertainty regarding their long-term effectiveness [22, 27].

Hand surgeons routinely prescribe opioids for pain relief, and there is an unexplained surgeon-to-surgeon variation in the amount of opioids prescribed [31]. Rodgers and colleagues [30] recently reported that opioids were overprescribed after elective outpatient upper extremity surgery, creating the potential for diversion, abuse, and accidental harm. Despite the pivotal role that providers play in maximizing the safe use of these drugs, little is known about hand surgeons’ views and practices regarding prescription opioid use. Given the current dimensions of the opioid epidemic, a better understanding of hand surgeons’ prescribing patterns and perceptions of adverse opioid-related events is central for patient safety and for the development of opioid management policies.

We undertook this study to examine hand surgeons’ attitudes, beliefs, and self-reported practices regarding the use of opioids. Additionally, we compared concerns about potential adverse patient and prescriber outcomes associated with opioid prescribing between hand surgeons and primary care physicians.

Materials and Methods

Survey Design and Administration

We conducted an online cross-sectional survey to determine attitudes, beliefs, and self-reported practices of hand surgeons regarding prescription opioid use. The survey was developed using the Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap; Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA) software [10], a secure web-based application designed to support data collection for clinical research. The survey consisted of 34 items, including nine demographic questions. Demographic data were age, sex, race/ethnicity, specialty (orthopedic surgery, plastic surgery, general surgery, other), practice type (solo, group, other) and setting (academic, private), the number of patients seen per month, number of surgeries performed per month, and number of patients prescribed an opioid per month. Of the 25 multiple-choice items related to prescription opioids (Appendix), 20 were adapted from a recent similar study by Hwang and colleagues [14] in primary care physicians.

Emails with a link to the online survey were sent to 3225 hand surgeons across the USA on January 7, 2015. The survey was open for 2 weeks. Our institutional review board approved this study, and consent was implied by completion of the survey. No compensation was offered for participation.

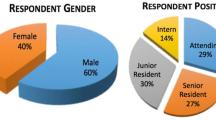

Respondent Characteristics

A total of 502 hand surgeons completed the survey, for a response rate of 16 %. Retired hand surgeons (n = 10) were excluded to keep the study population uniform and relevant to current practice standards, thus leaving 492 respondents for data analysis (Table 1).

The majority of respondents were men (87 %), white (90 %), and orthopedic surgeons (84 %). The mean (±SD) age was 49 (±11) years, and 65 % were private practitioners. On average, hand surgeons reported seeing 310 (±167) patients per month, performing 43 (±21) surgeries per month, and prescribing opioids to 49 (±30) patients per month.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis involved descriptive statistics. Continuous variables were presented in terms of the mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables were reported with percentages.

We used two-sample tests of proportions to compare our findings with those of Hwang and colleagues [14] in primary care physicians. Specifically, we compared the rate of concern about potential adverse patient and prescriber outcomes associated with opioid prescribing between hand surgeons and primary care physicians. For these comparisons, respondents were considered “concerned” if they rated their answer as “very” or “moderately” concerned. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Most hand surgeons (76 %) reported prescription opioid abuse to be a big or moderate problem in their communities, and 89 % felt that opioids are overused to treat pain (Table 2).

Nearly all hand surgeons (94 %) were very or moderately confident about their clinical skills regarding opioid prescribing. Nevertheless, fewer than half (40 %) reported always or often asking about a history of opioid abuse or dependence before scheduling surgery. Most (75 %) were very or moderately comfortable refilling opioid prescriptions following hand and wrist fracture surgery, while only 13 % were comfortable doing so after minor elective hand surgery. Only 3.8 % were comfortable prescribing opioids for chronic nonspecific arm pain.

Many hand surgeons reported being very or moderately concerned about potential adverse outcomes including opioid-related deaths (37 %), motor vehicle accidents (53 %), sedation (57 %), impaired cognition (58 %), nonadherence (59 %), tolerance (66 %), and addiction (67 %). When prescription opioids are used as directed, hand surgeons generally agreed that the frequency of adverse events (e.g., addiction, hyperalgesia, physical dependence, ceiling effects, tolerance) is not high. Hand surgeons expressed relatively low degrees of concern for potential adverse prescriber outcomes (e.g., malpractice claim, prosecution, censure by state medical board).

Nearly half of all hand surgeons (49 %) reported being less likely to prescribe opioids compared to 1 year ago. Two-thirds (67 %) believed that the best approach to reduce postoperative opioid use is to discuss pain management and expectations with the patient before surgery.

Compared to primary care physicians, hand surgeons were less likely to be concerned about potential adverse patient outcomes, including opioid-related addiction (67 vs. 84 %, P < 0.001), deaths (37 vs. 70 %, P < 0.001), motor vehicle accidents (53 vs. 77 %, P < 0.001), tolerance (66 vs. 75 %, P = 0.033), impaired cognition (58 vs. 74 %, P < 0.001), and sedation (57 vs. 71 %, P < 0.001; Fig. 1). Hand surgeons were also less concerned about potential adverse prescriber outcomes such as malpractice claims (22 vs. 46 %, P < 0.001), prosecution (15 vs. 45 %, P < 0.001), and censure by state medical boards (16 vs. 44 %, P < 0.001; Fig. 2).

Discussion

Opioid prescriptions have risen dramatically over the last decade, largely driven by concerns in the late 1990s about the undertreatment of pain accompanied by aggressive marketing strategies from pharmaceutical companies [21]. Concurrently, there has been an increase in opioid abuse and dependence [16]. Providers, administrators, and policymakers are now faced with a vexing challenge to develop strategies to mitigate misuse while treating pain effectively. The fact that patient satisfaction—including satisfaction with pain management—is increasingly incentivized and publicly reported further complicates this situation, as satisfaction surveys may have the unintended effect of encouraging physicians to prescribe opioids in order to please patients and avoid financial penalties [1, 38]. Opioids are routinely prescribed after hand surgery, but there is limited research about surgeon variation in prescription patterns and attitudes toward the use of opioids. This information is important for quality improvement purposes and may have clinical and economic implications. We therefore set out to determine the attitudes, beliefs, and self-reported practices of hand surgeons regarding prescription opioid use. In addition, we compared the rate of concern about potential adverse opioid-related events between hand surgeons and primary care physicians.

Our analysis should be interpreted cautiously in light of its limitations. First, our data are based on self-report and prone to socially desirable bias [14, 37]. We minimized this potential by ensuring respondent confidentiality and avoiding leading questions. Second, although within the range reported for physician surveys [8, 18, 23, 24, 26], our low response rate (16 %) could be indicative of nonresponse bias and the findings may not be representative of all hand surgeons in the USA. Third, the survey instrument was not psychometrically evaluated to determine its reliability or content validity, but most items were based on a previously published survey of primary care physicians [14]. Fourth, employing a web-based survey introduces a selection bias in which technologically inclined respondents may dominate responses [20]. However, this is not a major concern among physicians, given that nearly all have access to the Internet and check their email several times a week [3, 4]. Finally, we used closed-ended questions rather than evaluating surgeons’ views in an open-ended manner. This approach is better suited for quantitative analysis but provides less insight into respondents’ thoughts and ideas.

Our findings suggest that hand surgeons have become aware of the extent and public health implications of the prescription opioid epidemic, and many are taking an active role by reducing their reliance on these products. Although we did not assess hand surgeons’ attitudes and beliefs over time, it is likely that increased publicity and awareness of prescription opioid abuse and its consequences may have contributed to these findings [14]. It can also be speculated that tightening regulations on opioid prescribing may have created a sentinel effect, making physicians more cautious regarding the use of these drugs and perhaps more willing to seek nonopioid alternatives for managing pain. Despite widespread concerns about overuse, nearly all hand surgeons surveyed (94 %) were very or moderately confident in their own ability to prescribe opioids appropriately. These high levels of self-perceived confidence regarding opioid prescribing might be partly explained by the notion that physicians generally perceive their own clinical skills and judgment as superior to that of their peers (“ego bias”) [35]. Most hand surgeons felt that, in order to reduce postoperative opioid use, it is critical to educate patients about pain management and expectations prior to surgery. Along these lines, Holman and colleagues [13] recently demonstrated that preoperative discussion of a 6-week opioid prescription limitation was effective in reducing opioid use after fracture surgery. Physician education is also emerging as a key element in reducing postoperative opioid use, and there is recent evidence of its successful implementation in hand surgery [31]. Stanek and colleagues [31] reported that the use of a simple educational assist device containing recommended prescription sizes for common hand operations was associated with reduced postoperative opioid prescribing. Another valid approach to reduce postoperative opioid prescribing is to use nonopioid analgesics when possible—something that is common practice in Europe [11]. It is our opinion that the use of nonopioid pain relievers after minor elective hand surgery should be encouraged and perhaps incentivized. Hand surgeons’ reluctance to ask about a history of opioid abuse or dependence before scheduling surgery is of note. Providers might consider asking potentially sensitive questions about drug misuse in the context of other behavioral and lifestyle (e.g., exercise, diet, weight control) questions, which could help both patient and surgeon feel more comfortable and minimize any perceived stigma or bias associated with the questions [28]. Routine use of prescription drug monitoring programs that digitally store controlled substance dispensing information might also help identify patients with behaviors suggestive of opioid diversion and “doctor shopping [7, 9, 25, 32].”

We found differences in the judged importance of problems associated with opioid prescribing between hand surgeons and primary care physicians in the USA. Hand surgeons tended to be less concerned about potential adverse patient and prescriber outcomes. Reasons for the observed differences merit further study, but because primary care physicians are more at the frontline of the opioid abuse epidemic, they may be more likely to encounter opioid-related adverse events than hand surgeons [36].

In conclusion, this study provides evidence that hand surgeons recognize the current dimensions and consequences of the prescription opioid crisis, and many have altered their opioid prescribing practices during the past 12 months. Although hand surgeons are less concerned than primary care doctors about potential adverse opioid-related events, they have similarly reduced their reliance on opioids. Additional research using pharmacy data is needed to confirm the extent to which hand surgeons’ reliance on prescription opioids is actually decreasing.

References

Alexander GC, Kruszewski SP, Webster DW. Rethinking opioid prescribing to protect patient safety and public health. JAMA. 2012;308(18):1865–6.

Armaghani SJ, Lee DS, Bible JE, et al. Preoperative narcotic use and its relation to depression and anxiety in patients undergoing spine surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2013;38(25):2196–200.

Bennett NL, Casebeer LL, Kristofco RE, et al. Physicians’ Internet information-seeking behaviors. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2004;24(1):31–8.

Casebeer L, Bennett N, Kristofco R, et al. Physician Internet medical information seeking and on-line continuing education use patterns. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2002;22(1):33–42.

Caudill-Slosberg MA, Schwartz LM, Woloshin S. Office visits and analgesic prescriptions for musculoskeletal pain in US: 1980 vs. 2000. Pain. 2004;109(3):514–9.

Deyo RA, Mirza SK, Turner JA, et al. Overtreating chronic back pain: time to back off? J Am Board Fam Med. 2009;22(1):62–8.

Gugelmann HM, Perrone J. Can prescription drug monitoring programs help limit opioid abuse? JAMA. 2011;306(20):2258–9.

Gurunluoglu R, Gurunluoglu A, Williams SA, et al. Current trends in breast reconstruction: survey of American Society of Plastic Surgeons 2010. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70(1):103–10.

Haffajee RL, Jena AB, Weiner SG. Mandatory use of prescription drug monitoring programs. JAMA. 2015.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–81.

Helmerhorst GT, Lindenhovius AL, Vrahas M, et al. Satisfaction with pain relief after operative treatment of an ankle fracture. Injury. 2012;43(11):1958–61.

Holman JE, Stoddard GJ, Higgins TF. Rates of prescription opiate use before and after injury in patients with orthopaedic trauma and the risk factors for prolonged opiate use. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(12):1075–80.

Holman JE, Stoddard GJ, Horwitz DS, et al. The effect of preoperative counseling on duration of postoperative opiate use in orthopaedic trauma surgery: a surgeon-based comparative cohort study. J Orthop Trauma. 2014;28(9):502–6.

Hwang CS, Turner LW, Kruszewski SP, et al. Prescription drug abuse: a national survey of primary care physicians. JAMA Intern Med. 2014.

Jones CM, Lurie P, Woodcock J. Addressing prescription opioid overdose: data support a comprehensive policy approach. JAMA. 2014.

Kuehn BM. Opioid prescriptions soar: increase in legitimate use as well as abuse. JAMA. 2007;297(3):249–51.

Kuehn BM. SAMHSA: pain medication abuse a common path to heroin: experts say this pattern likely driving heroin resurgence. JAMA. 2013;310(14):1433–4.

Lane LB, Starecki M, Olson A, et al. Carpal tunnel syndrome diagnosis and treatment: a survey of members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2014;39(11):2181–7. 11.

Lee D, Armaghani S, Archer KR, et al. Preoperative opioid use as a predictor of adverse postoperative self-reported outcomes in patients undergoing spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(11):e89.

Leinberry CF, Rivlin M, Maltenfort M, et al. Treatment of carpal tunnel syndrome by members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand: a 25-year perspective. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(10):1997–2003 e3.

Manchikanti L, Helm 2nd S, Fellows B, et al. Opioid epidemic in the United States. Pain Physician. 2012;15(3 Suppl):ES9–38.

Martell BA, O’Connor PG, Kerns RD, et al. Systematic review: opioid treatment for chronic back pain: prevalence, efficacy, and association with addiction. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(2):116–27.

Mayer JE, Dang RP, Duarte Prieto GF, et al. Analysis of the techniques for thoracic- and lumbar-level localization during posterior spine surgery and the occurrence of wrong-level surgery: results from a national survey. Spine J. 2014;14(5):741–8.

Mirzabeigi MN, Moore Jr JH, Mericli AF, et al. Current trends in vaginal labioplasty: a survey of plastic surgeons. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;68(2):125–34.

Morris BJ, Zumsteg JW, Archer KR, et al. Narcotic use and postoperative doctor shopping in the orthopaedic trauma population. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(15):1257–62.

Mroz TE, Lubelski D, Williams SK, et al. Differences in the surgical treatment of recurrent lumbar disc herniation among spine surgeons in the United States. Spine J. 2014;14(10):2334–43.

Noble M, Treadwell JR, Tregear SJ, et al. Long-term opioid management for chronic noncancer pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD006605.

Olfson M, Tobin JN, Cassells A, et al. Improving the detection of drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and depression in community health centers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2003;14(3):386–402.

Pletcher MJ, Kertesz SG, Kohn MA, et al. Trends in opioid prescribing by race/ethnicity for patients seeking care in US emergency departments. JAMA. 2008;299(1):70–8.

Rodgers J, Cunningham K, Fitzgerald K, et al. Opioid consumption following outpatient upper extremity surgery. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(4):645–50.

Stanek JJ, Renslow MA, Kalliainen LK. The effect of an educational program on opioid prescription patterns in hand surgery: a quality improvement program. J Hand Surg Am. 2015;40(2):341–6.

Twillman RK, Kirch R, Gilson A. Efforts to control prescription drug abuse: why clinicians should be concerned and take action as essential advocates for rational policy. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(6):369–76.

USA Today. Chasing the heroin resurgence [October 3, 2014]. Available from: http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation-now/2014/06/12/communities-across-usa-scramble-to-tackle-heroin-surge/9713463/.

Webster BS, Verma SK, Gatchel RJ. Relationship between early opioid prescribing for acute occupational low back pain and disability duration, medical costs, subsequent surgery and late opioid use. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(19):2127–32.

Weinstein ND. Optimistic biases about personal risks. Science. 1989;246(4935):1232–3.

Wenghofer EF, Wilson L, Kahan M, et al. Survey of Ontario primary care physicians’ experiences with opioid prescribing. Can Fam Physician. 2011;57(3):324–32.

Yeo H, Viola K, Berg D, et al. Attitudes, training experiences, and professional expectations of US general surgery residents: a national survey. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1301–8.

Zgierska A, Miller M, Rabago D. Patient satisfaction, prescription drug abuse, and potential unintended consequences. JAMA. 2012;307(13):1377–8.

Conflict of Interest

Mariano E. Menendez declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Jos J. Mellema declares that he has no conflict of interest.

David Ring declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Statement of Informed Consent

This study was an online cross-sectional survey, and consent was implied by completion of the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Type of study/level of evidence: Economic/Decision Analysis, Level V

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOC 36 kb)

About this article

Cite this article

Menendez, M.E., Mellema, J.J. & Ring, D. Attitudes and self-reported practices of hand surgeons regarding prescription opioid use. HAND 10, 789–795 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-015-9768-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11552-015-9768-5