Abstract

Morphological inventories and structures of languages in contact can converge by means of either increasing formal similarity (MAT borrowing), or structural congruence (PAT borrowing), or a combination of both (MAT&PAT borrowing). In order to understand whether and how these borrowing types covary with specific grammatical features and modules of grammar, I propose a typology of MAT and PAT borrowing that distinguishes between functional and realization levels and covers all areas of grammar that can be affected by borrowing. I exemplify selected subtypes of borrowing with a number of crosslinguistic cases focusing on morphology and morphosyntax.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

One of the possible triggers of grammatical change is language contact. Generally speaking, a source language (SL) can influence the grammar of a recipient language (RL) in two fundamentally distinct ways: either concrete material is taken over or abstract patterns are calqued. These fundamental types, which concern all components of grammar and are not specific to morphology, have been given many names in the literature, including ‘direct diffusion’ (Heath 1978:21), ‘direct transfer’ (Heath 1984; Weinreich 1953), ‘transfer of fabric’ (Grant 2002), ‘global copying’ (Johanson 2002), for the former, and called ‘replication’ (cf. Weinreich 1953:31 ‘replica language’), ‘indirect transfer’ (Silva-Corvalán 1994), ‘indirect diffusion’ (Heath 1978:21), ‘structural convergence’ (Heath 1984), ‘selective copying’ (Johanson 2002) and generally, ‘calque’ (Haugen 1950), for the latter. More recently the terminological pair introduced by Matras and Sakel (2007a) and Sakel (2007) of ‘matter borrowing’ (henceforth MAT borrowing) as opposed to ‘pattern borrowing’ (henceforth PAT borrowing) has become commonly used. Applying this dichotomy to morphology, MAT borrowing concerns actual morphological formatives, such as in (1), while PAT borrowing concerns morphological techniques, that is, structural patterns but no forms, as exemplified in (2).

-

(1)

MAT borrowing

a.

Turkish (RL)

b.

Persian (SL)

yengeç-vari

pishrow-var

crab-adjz

leader-adjz

‘crab-like’

‘leader-like’

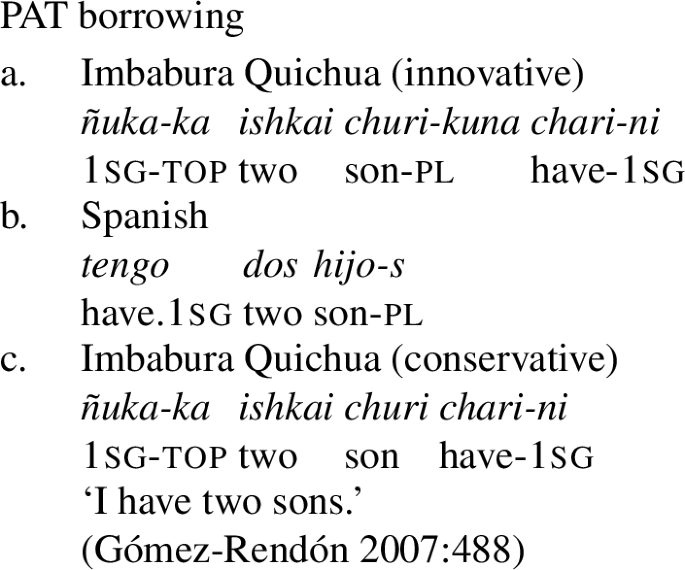

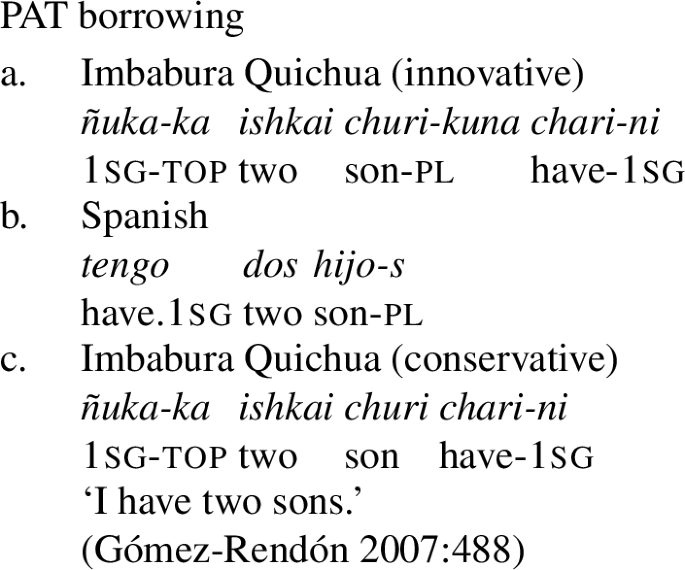

The data in (1a) exemplifies the borrowing of a formative, viz. the adjectivizer -vari meaning ‘resembling’ (and corresponding to English -like or -ish),Footnote 1 from Persian (1b), into Turkish, where the formative occurs on native lexical bases such as yengeç ‘crab’ (Gardani 2020:104; Seifart 2013).Footnote 2 The data in (2) showcases the borrowing of a pattern, viz. the overt marking of plural on nouns, when these follow numerals, in Imbabura Quichua, a Quechua language spoken in the Northern Andes of Ecuador, which has been in contact with Spanish since the second half of the sixteenth century (Gómez-Rendón 2007:481). While plural marking is generally obligatory in Imbabura Quichua, it is not when a noun is preceded by a numeral (Cole 1982:128), as in (2c). However, in contemporary Imbabura Quichua there is an increasing tendency to mark plural also on nouns preceded by a numeral, as in (2a), most likely as an effect of contact with Spanish (2b). In contrast to (1), thus, there is no material transfer in (2), as plural marking is implemented by an Imbabura Quichua formative, viz. -kuna.

-

(2)

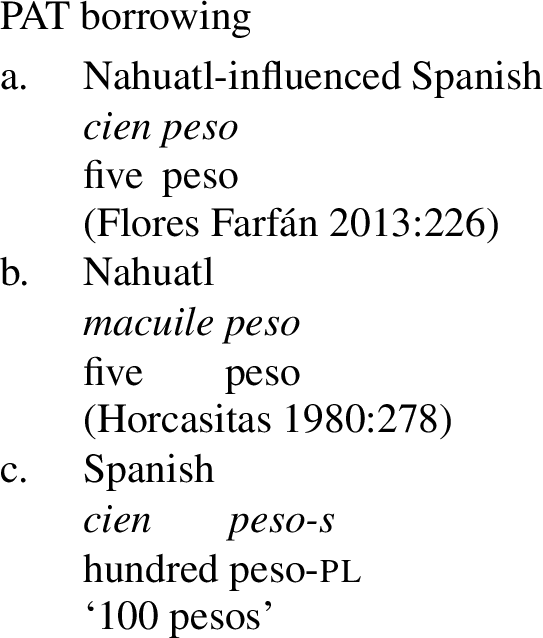

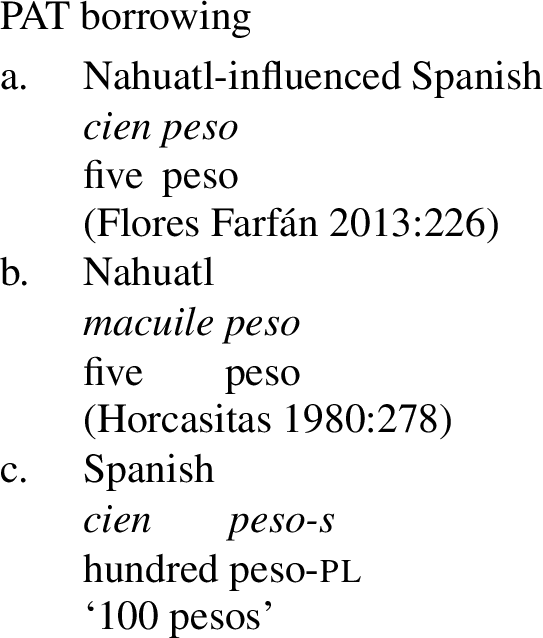

While the case of borrowing in (2) is ‘additive’, that is, the SL feeds the RL, borrowing can also lead to loss of a pattern (or formative), that is, an SL bleeds an RL (see Gardani forthcoming:§30.2). Interestingly enough, we observe the type of change occurred in (2), but in its ‘subtractive’ version, in Spanish varieties influenced by Nahuatl: here, probably as an effect of SL-agentivity (van Coetsem 1988, 2000), the absence of plural marking after numerals in Nahuatl (3b) has been borrowed as a morphosyntactic pattern into local varieties of Spanish, as exemplified in (3a).

-

(3)

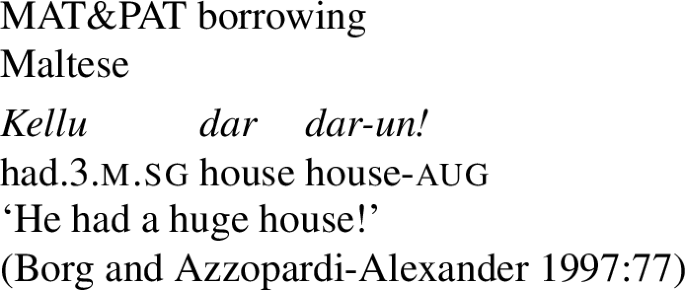

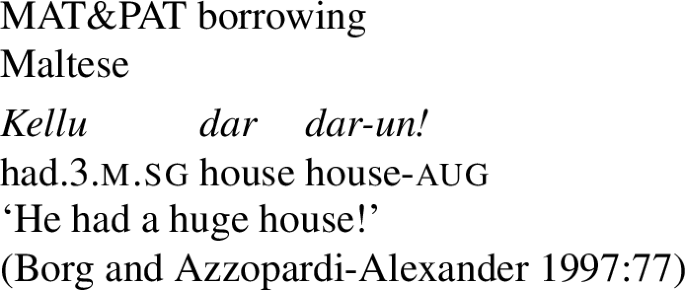

When analyzing cases that we suspect to be instances of PAT borrowing, its immaterial character, that is, the absence of concrete phonological form, is an obstacle to proving a language-contact hypothesis. By contrast, in the case of MAT borrowing, as we have seen above, similarity of formatives is a good piece of evidence in favor of a borrowing hypothesis. The more so as MAT borrowing and PAT borrowing are not necessarily mutually exclusive phenomena. As correctly noted by Sakel (2007:15), “[i]n many cases of MAT-borrowing, also the function of the borrowed element is taken over, that is MAT and PAT are combined”.Footnote 3 Therefore, when investigating the origin of grammatical change and pondering language-internal development explanations against contact-induced change explanations, evidence in favor of a borrowing hypothesis is strengthened when both the new pattern and the formative realizing it are borrowed. For example, the presence of both an augmentative suffix -ūn and the morphosemantic value augmentative in Maltese (4) is due to contact with Italo-Romance (cf. Italian -one) (Grandi 2004:70; see also Vicente 2020:234 for a related case of borrowing from Ibero-Romance in Andalusi Arabic). See the following data where the augmentative suffix -un applies to a native Maltese (i.e., Semitic) lexical base:

-

(4)

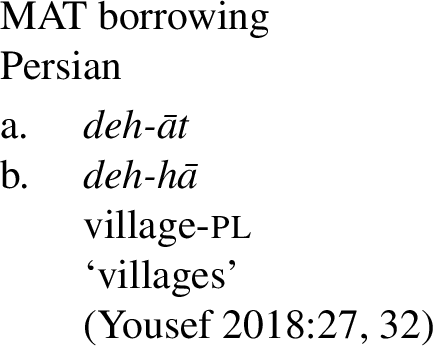

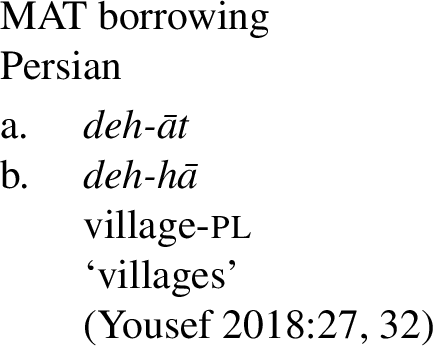

While Sakel (2007) is right in acknowledging that MAT and PAT borrowing can be combined, her analysis is wrong when she claims that “MAT-borrowing without any PAT […] is very rare and mainly occurs in the lexicon” (Sakel 2007:26): as an example of MAT-only borrowing in the lexicon, she adduces the case of the noun Handy ‘mobile phone’ in German, because in the SL, English, handy has a different meaning. Sakel’s mistake, probably influenced by a morpheme-based approach to inflection, is that she classifies MAT vs PAT focusing on an SL only and without considering the grammatical inventories of both the SL and the RL. In fact, however, borrowing can be of additive, replacive, and subtractive type (Breu 1996; Gardani forthcoming, 2008:22–23), in two respects: in terms of a) formatives and/or b) feature values. Often times, an additive borrowing is simply addition of a form(ative) and not of a feature value, as this already exists in the grammar of an RL. This is, for example, the case of Persian, where the Arabic-borrowed suffix -āt applies to Arabic, Mongolian, and Turkish loans as well as to some genuine Persian bases such as deh ‘village’ as in (5a); at the same time, plural can be realized on the same lexeme deh by means of a native Persian suffix -hā, as in (5b).

-

(5)

Because the feature value of plural already exists in the RL, we need to analyze the borrowing of a formative -āt (5a) realizing exactly the same morphosyntactic value as MAT-only borrowing and not as a combined MAT and PAT borrowing, as Sakel’s proposal (2007) would lead us to. As larger empirical collections (Gardani 2012; Seifart 2013) show us, this is by no means an isolated case. Therefore, I propose to distinguish three, and not two, types of borrowing depending on the effect of borrowing on the grammar of an RL: MAT borrowing as in (1) and (5), PAT borrowing as in (2) and (3), and MAT&PAT borrowing as in (4).

The classification of different types of borrowing as proposed for the cases seen thus far seems rather straightforward. However, things are often more complex, as we shall see in the following sections. The aim of the present article, which itself serves as an introduction to a special issue dedicated to borrowing matter and pattern in morphology, is to provide a principled classification of borrowing types such as MAT, PAT, and MAT&PAT. The rationale for a precise classification of this sort is the assumption that different types may covary with types of realized grammatical features, a hypothesis that has never been put forward explicitly and tested in the literatureFootnote 4 and that is worth investigating in future research.

This article is structured as follows: in Sect. 2, I show what analytical problems arise when classifying types of grammatical and specifically morphological borrowing. In Sect. 3, I outline a proposal for a general classification of MAT and PAT borrowing and discuss several subtypes with respect to morphology. Section 4 concludes the article and summarizes the eight contributions to the special issue.

2 Problems

The topic of this article, and of the special issue introduced by it, is borrowing matter and pattern in morphology. In the case of MAT borrowing, the borrowing of morphological formatives does not present major classificatory problems for we can easily say what kind of grammatical feature a formative realizes, but when dealing with PAT borrowing as involving the “organization, distribution and mapping of grammatical or semantic meaning, while the form itself is not borrowed” (Sakel 2007:15), we encounter several analytical and classificatory problems, especially as regards what area of grammar is affected by borrowing. Consider, by way of example, the change occurred in Molise Slavic, a variety of Croatian spoken in Molise (Italy), under the influence of Italo-Romance varieties and Italian. As a result of contact, the comparative degree of adjectives is now realized periphrastically (6a) on the model of Italian (6b), as opposed to synthetic comparative formation in Standard Croatian (6c) (Breu 1996:26).

-

(6)

a.

Molise Slavic

b.

Italian

c.

Croatian

veče

lip

più

bello

ljepši

more

pretty

more

pretty

pretty.comp

‘prettier’

‘prettier’

‘prettier’

While the role of language contact and the resulting structural convergence are pretty clear, it is not necessarily clear how to classify this case: in Croatian, comparative is realized synthetically and pertains to the domain of morphology; in Italian, however, comparative is generally realized by a periphrasis made up of an adverb and an adjective, as it does in Molise Slavic. Now, periphrastic constructions are strictly speaking syntactic, and this is exactly what comparative constructions (Stolz 2013) are when considering the whole comparative scheme including the comparee, the standard, and the parameter, that is, the property in terms of which they are compared (cf. Dixon 2008:788). But often the morphological literature treats comparatives, and superlatives, too, as morphological categories. Undoubtedly, this treatment results from analytical biases imposed by the grammatical tradition of Latin, where the three degrees of an adjective constitute a paradigm (e.g., positive longus ‘long, tall’—comparative longior—superlative longissimus); this paradigmatic analysis has been mapped onto many modern European languages where often synthetically and periphrastically realized comparatives coexist (e.g., better vs more lovable in English), a condition that favors considering different degrees of adjectives as different values of a grammatical feature ‘degree’ that, while couched within the same paradigm, are realized in different components of grammar, in morphology (i.e., synthetically) or in syntax (i.e., periphrastically) (for a discussion, see Brown et al. 2012). My personal view is that the positive, comparative, and superlative (etc.) degrees of adjectives (and adverbs) are not as ‘tight paradigms’ as those represented, for example, by the cells realizing case values; therefore, when in a certain language these three categories are realized in a non-uniform way (say, inflectionally, periphrastically, lexically) including a periphrasis, the periphrastic comparative is generated in syntax rather than in morphology. But an ultimate solution is hard to find, if at all, and this is not the place to find a solution but to address problems. However, what is particularly interesting in the Molise Slavic example is the replacement of a synthetic (morphological) pattern by a periphrastic pattern. This means that this PAT borrowing affects the morphology of the RL, while not involving any transfer of a morphological pattern from the SL.

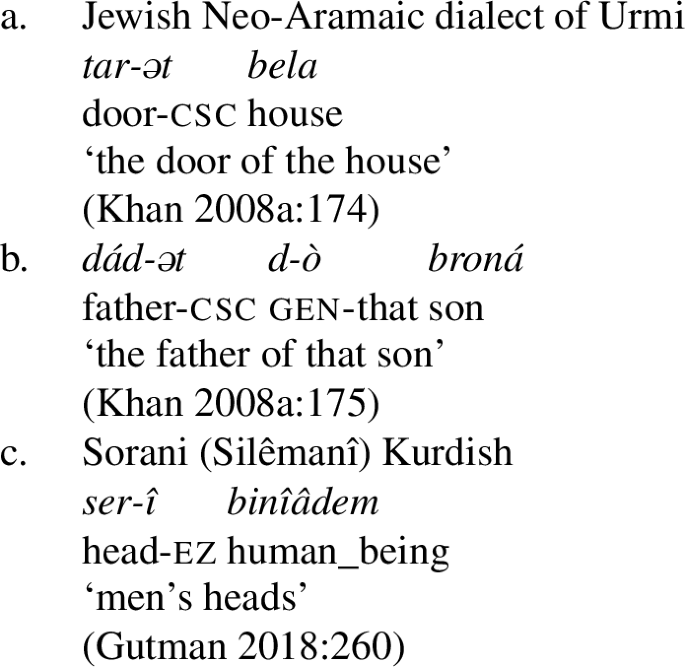

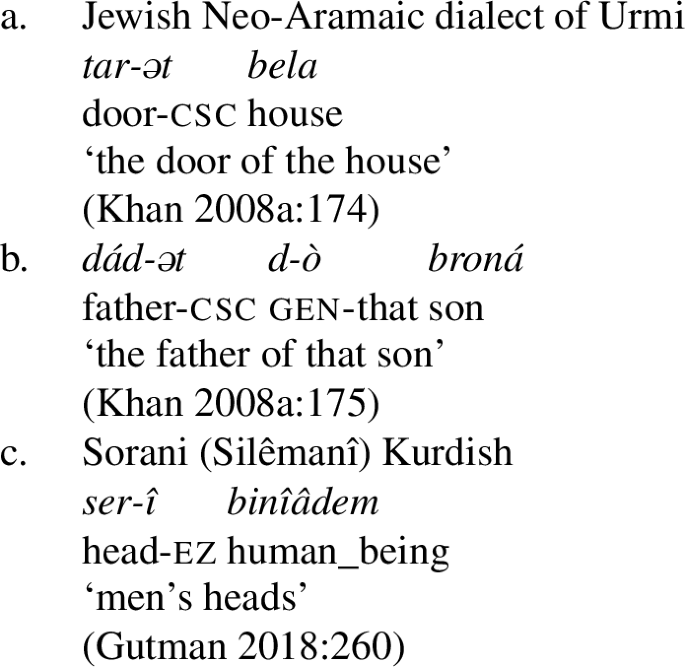

Problems become even more evident when we consider cases such as the following. In the Jewish Neo-Aramaic dialect of Urmi (north-western Iran), there exists an attributive (also genitive/possessive) construction X-əd Y as in (7a): it is made up of a head noun X suffixed by -əd (or -ət) and followed by a dependent noun Y. This construction, also known as ‘construct state construction’ (csc), occurs in Neo-Aramaic varieties in contact with Kurdish, such as the dialects of Barwar (Khan 2008b:§§10.16 and 14.5) and of Jewish Zakho (Cohen 2015) and is generally considered to be a calque of the Kurdish Ezafe construction, that is, a head-marking possessive construction of the type in (7b) (see Garbell 1965:171; Khan 2008a:176; and Gutman 2018:307–320, for detailed discussions).

-

(7)

Etymologically, this suffix appears to be related to the Classical Aramaic genitive prefix d- (Khan 2008a:175; Gutman 2018:189), remnants of which coexist with the csc in the Jewish Neo-Aramaic of Urmi, and sometimes even cooccurs with it (7b). Thus, what we observe in Jewish Urmi is the borrowing of the distributional property of the Kurdish Ezafe, but not of the contact language’s material. Therefore, it is PAT borrowing.

The question that is relevant to us here is how to classify the phenomenon in (7): is it morphological PAT borrowing? Or is it syntactic PAT borrowing? We know that this case involves a change occurred in the locus of morphological marking of the genitive, from dependent-marking to head-marking, and locus is the place where the syntactic relations within a phrase are marked, viz. on its head, on a dependent, or on both (Nichols and Bickel 2013). At the same time, the case involves the realization of a grammatical feature by means of suffixation—an overt morphological operation. Of course, a decision as to whether a change such as (7) is to be classified as morphological or syntactic (or belonging to other areas of grammar) might depend on the theoretical framework adopted by the analyst. And some might suggest that it is an instance of morphosyntactic borrowing, but in my opinion, there is no reason to call upon morphosyntax. We need to consider the case more carefully by answering two questions. First: how is a grammatical feature realized? That is, is it realized morphologically, syntactically, phonologically, prosodically, etc.? Second: what area of grammar does that feature belong to?

With respect to the Neo-Aramaic case in (7), my answers are that a), the feature in question is realized morphologically, by means of a formative and an operation of suffixation and b), while the feature is realized morphologically, it is also relevant to syntax and as such can be classified as morphosyntactic. In these terms, the borrowing instance exemplified in (7a) could qualify as morphological and/or morphosyntactic. But this is not the whole story. As a matter of fact, head vs dependent marking concerns the placement of morphological formatives in a phrase, therefore syntax is involved, too.Footnote 5 In reality, what we observe in (7) is a case of double borrowing, that is, of a morphological pattern (operation) and of a syntactic pattern.

Aiming at providing an instrument to classify grammatical borrowing phenomena in a more precise way, I propose a classification based on five identifiers:

-

a)

the grammatical features (and values) involved in the borrowing case;

-

b)

the areas of grammar the borrowed grammatical features (and values) supposedly pertain to;

-

c)

MAT vs PAT vs MAT&PAT borrowing;

-

d)

the realization of a MAT or PAT or MAT&PAT borrowing;

-

e)

maintenance vs change of meaning/function in RL vs SL.Footnote 6

Applying the identifiers to the case of Jewish Urmi in (7), we yield the following picture: a) two features: case (value: genitive) and locus (value: head); b) two areas of grammar: morphosyntax for case and syntax for locus; c) PAT borrowing; d) suffixation; e) identity.

By combining identifiers a), b), c) and d), I have elaborated a typology of matter and pattern borrowing that applies to all areas of grammar.Footnote 7 This is presented in Sect. 3 with particular emphasis on morphology.

3 Proposal for a classification of matter and pattern borrowing

In spite of the fact that the terminological distinction between MAT and PAT borrowing goes back to 2007Footnote 8 and has been well received in language contact research (for recent examples, see Hober 2019; Meyer 2019; Anderson 2020), so far there has not been any attempt at detailing subtypes of MAT and PAT borrowing. For example, we have seen that for PAT borrowing, Sakel (2007:15) speaks of “organization, distribution and mapping of grammatical or semantic meaning”, but what does this mean exactly? In particular, classifying borrowing cases concerning morphology is a tedious task, as we have seen in Sect. 2. This is because of the “double” nature of morphology, conflating form and meaning/function: for instance, in some languages a prototypical morphological feature such as inflectional class can be realized by prosodic means such as patterns of stress alternation (see, e.g., Corbett and Baerman 2006; Finkel and Stump 2007:45–47). For these reasons, in the context of morphological borrowing research, it appears particularly meaningful to adopt a realizational theory of morphology in the sense of Stump (2001:4), as this allows us to separately analyze the type of feature (as well as the area of grammar it belongs to) and the means by which that feature is realized.

In the following scheme (Scheme 1), I outline a typology of matter and pattern borrowing in spoken (vs signed) languages that distinguishes between functional levels (such as semantic and grammatical features) and realization levels (such as abstract devices and distributional and organizational properties) and covers all areas of grammar that are potentially subject to borrowing, viz. phonetics, phonology, prosody, morphology, morphosemantics, morphosyntax and syntax. The proposed typology has been developed based on a thorough analysis of the literature on grammatical borrowing and it is informed by morphological theory. My classification of feature types is mainly based on Corbett (2012); my classification of six morphological classes, viz. contextual, inherent, valency-changing, transpositional-only, evaluative and lexicon-expanding morphology,Footnote 9 is largely based on Bauer (2004) and partly overlapping with Dressler’s (1989, 1997) morphological architecture consisting of prototypical derivation, non-prototypical derivation, non-prototypical inflection and prototypical inflection.

Scheme 1: Typology of matter and pattern borrowing

-

1.

Types of MAT borrowing:

-

1.1

MAT borrowing of forms (phones; empty morphs)

-

1.2

MAT borrowing of forms capable of discriminating meaning (e.g., phonemes; tonal vowels)

-

1.3

MAT borrowing of forms capable of realizing semantic and grammatical features and values:

-

1.3.1

contextual-inflection formatives

-

1.3.2

inherent-inflection formatives

-

1.3.3

valency-changing formatives

-

1.3.4

transpositional-only formatives

-

1.3.5

evaluative formatives

-

1.3.6

lexicon-expanding formatives

-

1.3.1

-

1.1

-

2.

Types of PAT borrowing:

-

2.1

PAT borrowing of semantic and grammatical features or values thereof (“meaning”):

-

2.1.1

morphological features or values thereof (e.g., morphome, inflection class)

-

2.1.2

morphosyntactic features or values thereof (e.g., number distinctions; case distinctions)

-

2.1.3

morphosemantic features or values thereof (e.g., tense distinctions; aspect distinctions)

-

2.1.4

semantic features or values thereof (e.g., animacy distinctions)

-

2.1.1

-

2.2

PAT borrowing of abstract devices:

-

2.2.1

phonological processes (excluding their exact realization) (e.g., palatalization; metaphony)

-

2.2.2

phonological oppositions (e.g., voice: voiced vs non-voiced)

-

2.2.3

prosodic patterns (e.g., stress; tone system: high, mid, low, etc.)

-

2.2.4

morphological operations (e.g., affixation; compounding structures; reduplication)

-

2.2.5

periphrastic constructions (e.g., periphrastic comparative constructions)

-

2.2.6

morphosyntactic operations (e.g., agreement rules; passivization rules)

-

2.2.7

syntactic operations (e.g., wh-movement)

-

2.2.1

-

2.3

PAT borrowing of abstract properties of formatives or devices:

-

2.3.1

productivity

-

2.3.2

variationFootnote 10

-

2.3.3

frequencyFootnote 11

-

2.3.1

-

2.4

PAT borrowing of distributional and organizational properties:

-

2.4.1

phonotactic constraints (e.g., types of syllable structure)

-

2.4.2

morphotactic rules

-

2.4.3

type of morphological organization (e.g., synthetic vs analytic; agglutination; templatic structure)

-

2.4.4

parts-of-speech

-

2.4.5

clause types

-

2.4.6

syntactic distributions (e.g., alignment type; word order; locus of head/dependent marking in the clause)

-

2.4.1

-

2.1

-

3.

Types of MAT&PAT borrowing:

-

3.1

MAT&PAT borrowing of formatives realizing semantic and grammatical features or values thereof (“meaning”):

-

3.1.1

morphological features or values thereof (e.g., inflection class) and formatives realizing them

-

3.1.2

morphosyntactic features or values thereof (e.g., number; case) and formatives realizing them

-

3.1.3

morphosemantic features or values thereof (e.g., tense; aspect) and formatives realizing them

-

3.1.4

semantic features or values thereof (e.g., animacy) and formatives realizing them

-

3.1.1

-

3.2

MAT&PAT borrowing of abstract devices and their realization:

-

3.2.1

morphological operations and accompanying formatives (e.g., affixation types; compounding structures including SL compound markers)

-

3.2.2

periphrastic constructions and their realization (e.g., periphrastic comparative and the SL lexemes realizing them)Footnote 12

-

3.2.3

morphosyntactic and syntactic operations and their realization means (e.g., passivization rules and the SL lexemes realizing them)

-

3.2.1

-

3.3

MAT&PAT borrowing of distributional and organizational properties and their realization:Footnote 13

-

3.3.1

parts-of-speech and their realization

-

3.3.2

clause types and their realization

-

3.3.1

-

3.1

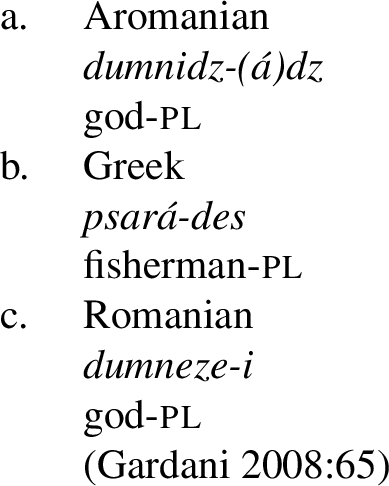

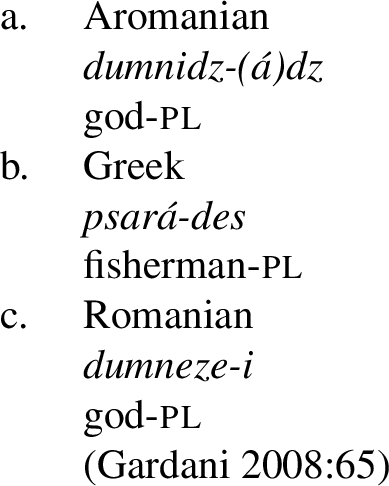

In the second part of this section, I zoom in on morphology and morphosyntax and present examples of some subtypes pertaining to these two areas of grammar. For reasons of space, the following empirical overview cannot showcase all subtypes listed in Scheme 1. Let us start with subtype 1.3, that is, ‘MAT borrowing of forms capable of realizing semantic and grammatical features and values’. This type implies that formatives are borrowed into an RL, although the feature values that they realize are not new to the RL. We can distinguish between several types of formatives: a first general distinction is that between inflectional and derivational formatives. In this respect, it appears that the borrowing of derivational formatives is more frequent than the borrowing of inflectional formatives. Elaborating on submodules of inflection (Booij 1996), Gardani (2008, 2012) found that a difference obtains in the degree of borrowability of formatives pertaining to inherent inflection (SUBTYPE 1.3.2) and those pertaining to contextual inflection (SUBTYPE 1.3.2) , with inherent-inflection formatives such as nominal plural being borrowed more frequently than contextual-inflection ones such as case. One such case of plural formative borrowing is found in the Eastern Romance language of Aromanian, spoken in southeastern Europe, which has borrowed the formative -(á)dz (9a) from Greek (9b).

-

(8)

Following the results concerning inherent and contextual inflection, Gardani conducted a pilot study on the borrowing of derivational formatives in a small number of typologically diverse languages (including seventeen RLs and fifteen SLs), applying a subdivision of morphology into classes as proposed by Bauer (2004). As reported in Gardani (2018:9), I found that the borrowing of lexicon-expanding formatives (SUBTYPE 1.3.6), such as agent, patient, and instrument noun formatives, outnumbers both the cases of borrowing of evaluative morphology (SUBTYPE 1.3.5) such as augmentative and diminutive formatives, and the cases of borrowing of transpositional-only formatives (SUBTYPE 1.3.4) such as those deriving action nouns and result nouns. However, despite recent efforts to provide crosslinguistic samples (see Seifart 2013, 2017), the datasets at our disposal are not yet comprehensive enough to make firm conclusions.

As concerns morphological PAT borrowing, there are, as I already said, virtually no overview studies. Nevertheless, it seems safe to claim that subtype 2.1.1 (‘borrowing of morphological features or values thereof’) must be extremely rare: no instance of the borrowing of morphomes (in the sense of Aronoff 1994) is known in the literature to date and as for the feature ‘inflectional class’, while it is a virtually possible type of PAT borrowing (and it therefore appears in Scheme 1), I can hardly imagine that such a feature is borrowed without the transfer of the material realizing it. But see a discussion of subtype 3.1.1 below.

As concerns subtype 2.2.6 (‘morphosyntactic operations’), an interesting case of morphosyntactic rule borrowing concerns the loss of an agreement pattern in Swiss German-Romansh bilingual children. Weinreich (2011[1951]:322) observed that in recorded productions such as (10a), those children failed to realize the mandatory Romansh rule which requires subject agreement on predicative adjectives (10c), in which the adjective is marked feminine singular, because of contact with Swiss German, that lacks this rule (10b).

-

(9)

a.

Romansh (innovative)

la

ʧa'pεʧa

ε

'koʧan

det.f.sg

hat(f).sg

is

red

b.

Swiss German

dr

huat

iě

ro:t

det.m.sg

hat(m).sg

is

red

c.

Romansh

la

ʧa'pεʧa

ε

'koʧna

det.f.sg

hat(f).sg

is

red.f.sg

‘The hat is red.’

(Weinreich 2011[1951]:322)

Among the few cases of borrowing of compounding structures known to me, one is found in Pharasiot (Bağrıaçık et al. 2017 and Ralli 2020), a Greek variety once spoken in Cappadocia that stood under heavy socio-cultural and linguistic contact with Turkish (Dawkins 1916). In Pharasiot, certain formations showing an Ngen N pattern such as in (11a) resemble the Turkish compounding structures (11c) and diverge from Hellenic-type compounds as in (11b). As is evident from the example, this resemblance is only partial (see a discussion in Gardani 2018:10–12).

-

(10)

a.

Pharasiot

b.

Modern Standard Greek

matráka-s

práða

ele-ó-dixto

frog.f-cm

leg.n.nom.pl

olive-cm-net

‘frog legs’

‘net for collecting olives’

c.

Turkish

el

çanta-sı

hand

bag-cm

‘handbag’

With respect to subtype 2.3 (‘PAT borrowing of abstract properties of a device’), the inclusion of morphological productivity (SUBTYPE 1.3.4) in Scheme 1 is owed to the paper contributed by Saade to this special issue. Saade (2020), which deals with the borrowing of Italo-Romance derivational formatives in Maltese as well as of their productivity rankings, is the first and thus far sole study produced on this topic. While one might argue that this is to be deemed a case of combined matter and pattern borrowing because the formatives themselves have been borrowed, I have chosen to not classify this case as MAT&PAT because productivity is not a property that comes along with single formatives, but a property emerging through the influx of sets of borrowed formatives or patterns.

As far as the MAT&PAT borrowing type is concerned, subtype 3.1.1, ‘borrowing of formatives realizing morphological features or values thereof (such as inflection class values) and the formatives realizing them’, is virtually unrecorded. The only case that I am aware of and that has been analyzed as such, is found in Korlai Indo-Portuguese, an Indo-Portuguese creole formed around the middle of the 16th century and now spoken in Korlai village, on the west coast of India, south of Mumbai. Clements and Luís (2015) claim that due to contact with Marathi, Korlai Indo-Portuguese has developed a new conjugation class (Class 4) into which roots of Marathi origin are integrated and which is realized by the stem vowel -u-, a formative borrowed from the Marathi imperative form, as example (12) shows. (For a different analysis, see Gardani 2016:244–245.)

-

(11)

a.

Korlai Indo-Portuguese

b.

Marathi

loʈ-u

loʈ-u

push-ic4

push-imp

‘to push’

‘push!’

(cf. Clements and Luís 2015:234)

The full paradigm of a verb belonging to Class 4 is given in (13), where the verb loṭú ‘push’ is juxtaposed to verbs belonging to the other inflectional classes, katá ‘sing’, bebé ‘drink’, and irgí ‘get up’.

-

(12)

Korlai Indo-Portuguese

Class 1

Class 2

Class 3

Class 4

‘sing’

‘drink’

‘get up’

‘push’

Unmarked

kat-á

beb-é

irg-í

loṭ-ú

Past

kat-ó

beb-é-w

irg-í-w

loṭ-ú

Gerund

kat-á-n

beb-é-n

irg-í-n

loṭ-ú-n

Completive

kat-á-d

beb-í-d

irg-í-d

loṭ-ú-d

(Clements and Luís 2015:228)

The ‘borrowing of a morphosyntactic features or values thereof and formatives realizing them’ (subtype 3.1.2) is documented, too. One such case, the borrowing of a gender value along with its formative, is found in Northern Istro-Romanian. The northern dialect of Istro-Romanian has borrowed from Croatian (14b) both the gender value ‘neuter’ and the suffix encoding it, viz. -o, which occurs both on nouns and on agreement targets such as the adjective ɣrév ‘heavy’ in (14a) (Kovačec 1968:87; Petrovici 1967:1526). Because Northern Istro-Romanian had lost the Latin-inherited neuter, this case qualifies as MAT&PAT borrowing.

-

(13)

a.

Northern Istro-Romanian

zrébro=j

ɣrév-o

silver(n).sg=is

heavy-n.sg

b.

Croatian

srebro

je

tešk-o

silver(n).sg

is

heavy-n.sg

‘silver is heavy’

An example of the MAT&PAT borrowing subtype ‘morphosemantic features and values thereof and formatives realizing them’ is the borrowing of aspectual distinctions in Istro-Romanian, an Eastern Romance language spoken in the Northeast of the Istrian peninsula, Croatia, as well as in the diaspora (e.g., in New York City). As reported by, among others, Arkadiev (2017), Klepikova (1960, 1963), Kovačec (1966), Pușcariu (1926) and Sârbu (1995), Istro-Romanian has borrowed from its contact language, Croatian, both the morphosemantic feature of aspect—with its values of imperfective vs perfective—and some dedicated formatives such as the prefix -za, which in the following example applies to a native Romance lexical base.

-

(14)

a.

Istro-Romanian

latrå

za-latrå

b.

Croatian

lajati

za-lajati

pfv-bark

‘bark(ipfv)’

‘bark(pfv/inchoative)’

I conclude this section with a case exemplifying MAT&PAT borrowing of abstract devices and their realization and in particular, its subtype ‘morphological operations and accompanying formatives’: it concerns the occurrence in Persian of the so-called ‘broken plural’, that is, plural forms realized by internal modification of the singular base; this operational pattern (generally known as ‘root-and-pattern morphology’) is not inherited in (Indo-European) Persian and was borrowed from Arabic (Semitic), the long-standing contact language of Persian. As a result of PAT borrowing, some native Persian nominal bases have broken plurals forms: for example, in (16a), the plural form of bostān ‘garden’, viz. basātīn, implements an Arabic abstract plural pattern (i.e., the template), CVCV:CV:C. Furthermore, the template (that is, the PAT) is itself realized by exactly the same set of vowel qualities and length (that it, the MAT) found in the plural template in Arabic, viz. CaCa:Ci:C (cf. Arabic ṣanādīq ‘boxes’ in (16b)).

-

(15)

a.

Modern Persian

b.

Arabic

bostān ‘garden’

ṣandūq ‘box’

basātīn ‘gardens’

ṣanādīq ‘boxes’

(Mumm 2007:41)

4 Conclusion and overview of the Special Issue

In this conceptual article, we have seen that the morphological inventories and structures of languages in contact can converge by means of either increasing formal similarity (MAT borrowing), or structural congruence (PAT borrowing), or a combination of both (MAT&PAT borrowing). In an attempt at understanding various borrowing types and studying covariation of borrowing types with types of realized grammatical features and areas of grammar affected by borrowing, I have proposed a classification of grammatical borrowing phenomena based on five identifiers (Sect. 2) and elaborated a fine-grained typology of MAT and PAT borrowing distinguishing between functional and realization levels and covering all areas of grammar that can be affected by borrowing (Sect. 3).

This article and the special issue Borrowing matter and pattern in morphology focus on morphology, as this is generally considered resistant to borrowing (Gardani et al. 2015) and rather understudied. The present special issue endeavors to fill this gap and aims to provide an empirical and theoretical coverage of the topic, in order to seize their global extension and incidence in morphological change.

The articles offer a good overview of which areas of morphology are borrowed, in terms of features (in the sense of Corbett 2012) and morphological operations. Six articles deal with contact settings which involve both matter borrowing and pattern borrowing of morphology, while the papers authored by Law, Klamer & Saad, and Meakins, Disbray & Simpson are exclusively concerned with the borrowing of patterns. Empirical evidence is drawn from South America (Ciucci; Law), North America (Mithun), Africa (Souag), Europe (Ralli; Saade), Asia (Klamer and Saad) and Oceania (Meakins, Simpson and Disbray). With respect to features, the papers deal with morphosyntactic features such as case (Meakins, Simpson and Disbray), number (Mithun), numeral classifier (Law), person (Ciucci) and morphosemantic features such as adjective degree (Souag). With respect to morphological operations, most papers cover affixation, while Klamer and Saad’s is dedicated to reduplication and Ralli’s to compounding. The case of compounding borrowing in four Asia Minor Greek varieties in contact with Turkish, investigated by Angela Ralli (Ralli 2020) in Matter versus pattern borrowing in compounding: Evidence from the Asia Minor Greek dialectal variety is of great importance in language contact research because the borrowing of compound patterns seems to be an extremely rare phenomenon (cf. Gardani 2018:10–12).

The papers are in-depth studies concerned with topics such as: the components of morphology affected by borrowing; the types of abstract patterns borrowed; the refunctionalization of borrowed formatives or patterns in an RL; the conditions promoting or inhibiting morphological borrowing; the areal aspects of morphological borrowing; the role of rule productivity in morphological borrowing. As regards the maintenance vs refunctionalization of borrowed formatives or patterns in an RL (see Sect. 2), in Which MATter matters in PATtern borrowing? The direction of case syncretisms Felicity Meakins, Samantha Disbray and Jane Simpson (Meakins et al. 2020) address the interesting question of which case value is favored in case realignment by examining two mixed varieties in northern Australia, Gurindji Kriol and Wumpurrarni English where case markers borrowed from two Australian languages, Gurindji and Warumungu, are no longer used in the same way as in their source languages. They show that the refunctionalization occurred as a result of mapping the original Australian case values onto the distribution of the functionally corresponding preposition in the contact language, Kriol, and argue that it is the case value with the broadest functional range which is generalized.

With respect to what conditions can promote or inhibit the spread of morphological borrowing, two main factors are in focus: the fundamental role played by structural compatibility between SL and RL and the sociological characteristics of the contact setting. The role of structural compatibility is stressed in the contributions by Law, Mithun, Ralli and Souag. For example, in Replicated inflectional matter? Plots twists behind apparent borrowed plurals, Marianne Mithun (Mithun 2020) examines the role of typological similarities among the languages involved in plural marking on nouns and shows that throughout the Northern California area (with three unrelated families, viz. Pomoan, Yukian, and Wintun), where inflectional number marking on nouns is rare, but related distinctions on verbs can be elaborate, verbal distributive and collective suffixes were transferred, which then evolved within the individual languages into number marking on nouns.

As for the sociological characteristics of contact setting as a variable that can promote or inhibit the spread of morphological borrowing, in Matter borrowing, pattern borrowing and typological rarities in the Gran Chaco of South America Ciucci (Ciucci 2020) discusses the war relationship between the Chamacoco and the Kadiwéu in Gran Chaco of South America and convincingly argues that the Kadiwéu’s incursions in the Chamacoco territory and the imprisonment of Chamacoco children to be incorporated into the Kadiwéu tribe, facilitated the spread of rare morphosyntactic features.

The areal dimension of morphological borrowing is explicitly addressed by Ciucci (focusing on the Gran Chaco), Law (focusing on Mayan languages), and Mithun (focusing on Northern California). All three papers highlight the role of pattern borrowing in the emergence of areal phenomena. These three papers also show the importance of the study of morphology in reconstructive historical linguistics, when it comes to areas characterized by uncertain or unknown genealogical relationships. This is particularly evident in Pattern borrowing, linguistic similarity, and new categories: Numeral classifiers in Mayan, by Danny Law (Law 2020). Law discusses the areal spread of numeral classifiers among Mayan languages as a case of pattern borrowing and argues that inherited grammatical categories related to quantification provided important preconditions for the development of similar systems of numeral classification across the family and that inherited linguistic matter facilitated the transfer of linguistic patterns, even as the forms themselves, already shared through common inheritance, were not borrowed.

A decisive factor in the making of linguistic areas is productivity, as it can have a boosting effect on the spread of borrowed formatives or patterns. However, productivity plays a central role independently from areal spread, namely in the process of nativization that morphological entities undergo after being borrowed, as is shown neatly in the papers by Klamer & Saad and by Souag. In Reduplication in Abui: A case of pattern extension, Marian Klamer and George Saad (Klamer and Saad 2020) study the effect of contact between Abui, a Papuan indigenous minority language of eastern Indonesia, and Alor Malay (Austronesian), the regional lingua franca, on the Abui reduplication system. They show that existing Abui verb reduplications become more Alor Malay-like also with respect to their productivity. In When is templatic morphology borrowed? On the spread of the Arabic elative, Lameen Souag (Souag 2020) discusses the borrowing of the Semitic comparative/superlative template ʔaCCaC into Siwi Berber, Western Neo-Aramaic, and Mehri, where it has become fully productive. A different view on productivity is taken by Benjamin Saade in Quantitative approaches to productivity and borrowing in Maltese derivation (Saade 2020). By applying quantitative measures of productivity to a selection of Maltese derivational affixes borrowed from Italo-Romance, Saade shows that the productivity rankings of the most productive affixes are identical in the SL and the RL, and that productivity is to be treated as a borrowable pattern itself.

Abbreviations

The abbreviations used in this paper are based on Lehmann (2004) and the Leipzig Glossing Rules. In addition, cm stands for compound marker, csc for construct state construction, and ic for inflectional class.

Notes

Note that Turkish has native suffixes expressing this meaning, such as -(i)mtrak (e.g., beyazımtrak ‘whitish’) and -imsi (e.g., duvarımsı ‘wall-like’) (cf. Lewis 2000:55).

Note that in the 1960s, this suffix ranked very low in the suffix frequency hierarchy compiled for written Turkish by Pierce (1962:40).

Borrowing this combination of form and function is exactly what Johanson (e.g., 2000:291) refers to as ‘global copying’.

The idea in nuce is implicit in the following quote from Matras and Sakel (2007b:844): “Some categories seem to resist MAT but attract PAT”, but it has been left without any follow-up.

Someone might argue that locus is morphology: in Dryer and Haspelmath’s (2013) WALS, locus of marking is classified as a morphological feature in spite of the specification “in the clause”.

For an overview of cases in which the original function of a borrowed formative and/or pattern in the SL is not maintained in the RL, see Gardani (2016).

Identifier e) concerns change in function of borrowed formatives or patterns and is relevant for the phenomenon that I have dubbed ‘allogenous exaptation’ (see Gardani 2016).

As a matter of fact, the history of this distinction, although expressed with different terms, is much older in contact linguistics, as we have seen in Sect. 1.

Transpositional-only morphology has the sole function of effecting a transposition from one part-of-speech to another without producing any semantic change, such as in the formation of action nouns.

According to Johanson (2002:292), “frequency patterns peculiar to model code units [can be] copied onto units of the basic code so that the latter undergo an increase or a decrease in frequency of occurrence.” I am much indebted to Peter Arkadiev for bringing this concept to my attention.

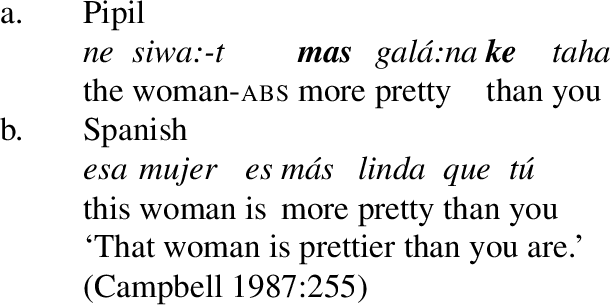

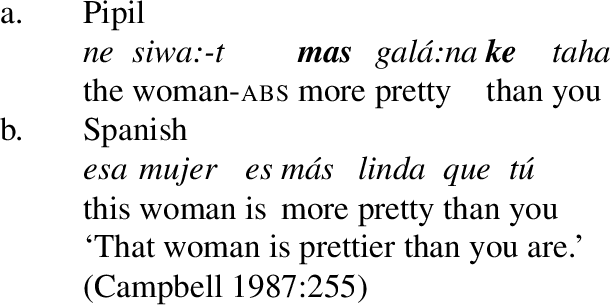

For example, Pipil, a Uto-Aztecan language spoken in western El Salvador, borrowed from Spanish the comparative construction consisting of comparee index parameter mark standard, as well as the lexeme realizing the index, mas (cf. Spanish más), and that realizing the mark, ke (cf. Spanish que), as shown in the following example:

-

A.

Crucially, the Spanish syntactic construction has no match with the native Uto-Aztecan comparative constructions listed in Andrews (2003:563–566) and Langacker (1977:116–118), which are all lost in Pipil. This is why we can safely say that the pattern was borrowed, as well.

-

A.

This type would be, for example, the borrowing of a part-of-speech not existent in an RL (say, adverbs) and the lexical material themselves or the borrowing of a clause type and a concurrent conjunction.

References

Anderson, G. D. S. (2020). Form and pattern borrowing across Siberian Turkic, Mongolic, and Tungusic languages. In M. Robbeets & A. Savelyev (Eds.), The Oxford guide to the Transeurasian languages (pp. 715–725). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Andrews, J. R. (2003). Introduction to Classical Nahuatl. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Arkadiev, P. (2017). Borrowed prefixes and the limits of contact-induced change in aspectual systems. In R. Benacchio, A. Muro, & S. Slavkova (Eds.), The role of prefixes in the formation of aspectuality: Issues of grammaticalization (pp. 1–21). Firenze: Firenze University Press.

Aronoff, M. (1994). Morphology by itself: Stems and inflectional classes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bağrıaçık, M., Göksel, A., & Ralli, A. (2017). Copying compound structures: The case of Pharasiot Greek. In C. Trips & J. Kornfilt (Eds.), Further investigations into the nature of phrasal compounding (pp. 185–231). Berlin: Language Science Press.

Bauer, L. (2004). The function of word-formation and the inflection-derivation distinction. In H. Aertsen, M. Hannay, & R. Lyall (Eds.), Words in their places: A festschrift for J. Lachlan Mackenzie (pp. 283–292). Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit.

Booij, G. E. (1996). Inherent versus contextual inflection and the split morphology hypothesis. In G. E. Booij & J. van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology 1995 (pp. 1–16). Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Borg, A., & Azzopardi-Alexander, M. (1997). Maltese. London: Routledge.

Breu, W. (1996). Überlegungen zu einer Klassifikation des grammatischen Wandels im Sprachkontakt (am Beispiel slavischer Kontaktfälle). Sprachtypologie und Universalienforschung (STUF), 49, 21–38.

Brown, D., Chumakina, M., Corbett, G. G., Popova, G., & Spencer, A. (2012). Defining ‘periphrasis’: Key notions. Morphology, 22(2), 233–275.

Campbell, L. (1987). Syntactic change in Pipil. International Journal of American Linguistics, 53(3), 253–280.

Ciucci, L. (2020). Matter borrowing, pattern borrowing and typological rarities in the Gran Chaco of South America. Morphology, 30(4).

Clements, J. C., & Luís, A. R. (2015). Contact intensity and the borrowing of bound morphology in Korlai Indo-Portuguese. In F. Gardani, P. Arkadiev, & N. Amiridze (Eds.), Borrowed morphology (pp. 219–240). Berlin/Boston/Munich: De Gruyter Mouton.

Cohen, E. (2015). Head-marking in Neo-Aramaic genitive constructions and the ezafe construction in Kurdish. In A. Butts (Ed.), Semitic languages in contact (pp. 114–126). Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Cole, P. (1982). Imbabura Quechua. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

Corbett, G. G. (2012). Features. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Corbett, G. G., & Baerman, M. (2006). Prolegomena to a typology of morphological features. Morphology, 16(2), 231–246.

Dawkins, R. M. (1916). Modern Greek in Asia Minor: A study of the dialects of Sílli, Cappadocia and Phárasa with grammar, texts, translations and glossary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dixon, R. M. W. (2008). Comparative constructions: A cross-linguistic typology. Studies in Language, 32(4), 787–817.

Dressler, W. U. (1989). Prototypical differences between inflection and derivation. Zeitschrift für Phonetik, Sprachwissenschaft und Kommunikationsforschung, 42(1), 3–10.

Dressler, W. U. (1997). Universals, typology, and modularity in natural morphology. In R. Hickey & S. Puppel (Eds.), Language history and linguistic modelling: A festschrift for Jacek Fisiak on his 60th birthday. Vol. 2: Language history and linguistic modelling (pp. 1399–1421). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Dryer, M. & Haspelmath, M. (Eds.) (2013). The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. http://wals.info.

Finkel, R., & Stump, G. (2007). Principal parts and morphological typology. Morphology, 17(1), 39–75.

Flores Farfán, J. A. (2013). Spanish in contact with indigenous tongues: Changing the tide in favor of the heritage languages. In S. T. Bischoff, D. Cole, A. V. Fountain, & M. Miyashita (Eds.), The persistence of language: Constructing and confronting the past and present in the voices of Jane H. Hill (pp. 203–227). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Garbell, I. (1965). The impact of Kurdish and Turkish on the Jewish Neo-Aramaic dialect of Persian Azerbaijan and the adjoining regions. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 85(2), 159–177.

Gardani, F. (2008). Borrowing of inflectional morphemes in language contact. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

Gardani, F. (2012). Plural across inflection and derivation, fusion and agglutination. In L. Johanson & M. I. Robbeets (Eds.), Copies versus cognates in bound morphology (pp. 71–97). Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Gardani, F. (2016). Allogenous exaptation. In M. Norde & F. Van de Velde (Eds.), Exaptation and language change (pp. 227–260). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Gardani, F. (2018). On morphological borrowing. Language and Linguistics Compass, 12(10), [1–17].

Gardani, F. (2020). Morphology and contact-induced language change. In A. Grant (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of language contact (pp. 96–122). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gardani, F. (forthcoming). Contact and borrowing. In A. Ledgeway & M. Maiden (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of Romance linguistics, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gardani, F., Arkadiev, P., & Amiridze, N. (2015). Borrowed morphology: An overview. In F. Gardani, P. Arkadiev, & N. Amiridze (Eds.), Borrowed morphology (pp. 1–23). Berlin/Boston/Munich: De Gruyter Mouton.

Gómez-Rendón, J. (2007). Grammatical borrowing in Imbabura Quichua. In Y. Matras & J. Sakel (Eds.), Grammatical borrowing in cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 481–521). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Grandi, N. (2004). Gli effetti dell’interferenza sui sistemi morfologici. In G. Garzone & A. Cardinaletti (Eds.), Lingua, mediazione linguistica e interferenza (pp. 65–84). Milano: Franco Angeli.

Grant, A. (2002). Fabric, pattern, shift and diffusion: What change in Oregon Penutian languages can tell historical linguists. In L. Buszard-Welcher (Ed.), Proceedings of the meeting of the Hokan-Penutian workshop, June 17–18, 2000: Report 11, survey of California and other Indian languages (pp. 33–56). Berkeley: University of California at Berkeley.

Gutman, A. (2018). Attributive constructions in North-Eastern Neo-Aramaic. Berlin: Language Science Press.

Haugen, E. (1950). The analysis of linguistic borrowing. Language, 26(2), 210–231.

Heath, J. (1978). Linguistic diffusion in Arnhem Land. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Heath, J. (1984). Language contact and language change. Annual Review of Anthropology, 13, 367–384.

Hober, N. (2019). On the intrusion of the Spanish preposition de into the languages of Mexico. Journal of Language Contact, 12(3), 660–706.

Horcasitas, F. (1980). La Danza de los Tecuanes. Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl, 14, 239–286.

Johanson, L. (2002). Contact-induced change in a code-copying framework. In M. C. Jones & E. Esch (Eds.), Language change: The interplay of internal, external, and extra-linguistic factors (pp. 285–314). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Khan, G. (2008a). The Jewish Neo-Aramaic dialect of Urmi. Piscataway: Gorgias Press.

Khan, G. (2008b). The Neo-Aramaic dialect of Barwar. Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Klamer, M., & Saad, G. (2020). Reduplication in Abui: A case of pattern extension. Morphology, 30(4).

Klepikova, G. P. (1960). Funcțiile prefixelor verbale de origine slavă în dialectul istroromîn. Fonetică şi Dialectologie, 2, 169–207.

Klepikova, G. P. (1963). Prefixul de origine slavă po- în dialectul istroromîn. Fonetică şi Dialectologie, 5, 69–81.

Kovačec, A. (1966). Quelques influences croates dans la morphosyntaxe istroroumaine. Studia Romanica et Anglica Zagabriensia, 21–22, 57–75.

Kovačec, A. (1968). Observations sur les influences croates dans la grammaire istroroumaine. La Linguistique, 4(1), 79–115.

Law, D. (2020). Pattern borrowing, linguistic similarity, and new categories: Numeral classifiers in Mayan. Morphology, 30(4).

Langacker, R. W. (1977). Studies in the Uto-Aztecan grammar. Vol. 1: An overview of Uto-Aztecan grammar. Dallas: Summer Institute of Linguistics.

Lehmann, C. (2004). Interlinear morphemic glossing. In: in collaboration, G. E. Booij, C. Lehmann, J. Mugdan, & W. Kesselheim (Eds.), Morphology. An international handbook on inflection and word-formation (Vol. 2, pp. 1834–1857). Berlin: de Gruyter.

Lewis, G. (2000). Turkish grammar (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Matras, Y., & Sakel, J. (2007a). Introduction. In Y. Matras & J. Sakel (Eds.), Grammatical borrowing in cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 1–13). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Matras, Y., & Sakel, J. (2007b). Investigating the mechanisms of pattern replication in language convergence. Studies in Language, 31(4), 829–865.

Meakins, F., Disbray, S., & Simpson, J. (2020). Which MATter matters in PATtern borrowing? The direction of case syncretisms. Morphology, 30(4).

Meyer, R. (2019). The relevance of typology for pattern replication. Journal of Language Contact, 12(3), 569–608.

Meyerhoff, M. (2009a). Animacy in Bislama? Using quantitative methods to evaluate transfer of a substrate feature. In J. N. Stanford & D. R. Preston (Eds.), Variation in indigenous minority languages (pp. 369–396). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Meyerhoff, M. (2009b). Replication, transfer, and calquing: Using variation as a tool in the study of language contact. Language Variation and Change, 21(3), 297–317.

Mithun, M. (2020). Replicated inflectional matter? Plots twists behind apparent borrowed plurals. Morphology, 30(4).

Mumm, P.-A. (2007). Strukturkurs Neupersisch. München: Universität München.

Nichols, J., & Bickel, B. (2013). Locus of marking in the clause. In M. Dryer & M. Haspelmath (Eds.), The World Atlas of Language Structures Online, Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. http://wals.info.

Petrovici, É. (1967). Le neutre en istro-roumain. In To honor Roman Jakobson: Essays on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, 11 October 1966 (pp. 1523–1526). The Hague/Paris: Mouton.

Pierce, J. E. (1962). Frequencies of occurrence for affixes in written Turkish. Anthropological Linguistics, 4(6), 30–41.

Pușcariu, S. (1926). Studii istroromâne: Introducere, gramatică, caracterizarea dialectului istroromân. București: Editura Cultura Națională.

Ralli, A. (2020). Matter versus pattern borrowing in compounding: Evidence from the Asia Minor Greek dialectal variety. Morphology, 30(4).

Saade, B. (2020). Quantitative approaches to productivity and borrowing in Maltese derivation. Morphology, 30(4).

Sakel, J. (2007). Types of loan: Matter and pattern. In Y. Matras & J. Sakel (Eds.), Grammatical borrowing in cross-linguistic perspective (pp. 15–29). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Sârbu, R. (1995). Aspectul verbal în dialectul istroromân. In S. Drincu, I. Funeriu, & F. Király (Eds.), G.I. Tohăneanu 70 (pp. 469–477). Timişoara: Editura Amphora.

Seifart, F. (2013). AfBo: A world-wide survey of affix borrowing. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. Available online at http://afbo.info.

Seifart, F. (2017). Patterns of affix borrowing in a sample of 100 languages. Journal of Historical Linguistics, 7(3), 389–431.

Silva-Corvalán, C. (1994). Language contact and change: Spanish in Los Angeles. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Souag, L. (2020). When is templatic morphology borrowed? On the spread of the Arabic elative. Morphology, 30(4).

Stolz, T. (2013). Competing comparative constructions in Europe. Berlin: Akademie Verlag.

Stump, G. T. (2001). Inflectional morphology: A theory of paradigm structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

van Coetsem, F. (1988). Loan phonology and the two transfer types in language contact. Dordrecht & Providence: Foris Publications.

van Coetsem, F. (2000). A general and unified theory of the transmission process in language contact. Heidelberg: Winter.

Vicente, Á. (2020). Andalusi Arabic. In C. Lucas & S. Manfredi (Eds.), Arabic and contact-induced change (pp. 225–244). Berlin: Language Science Press.

Weinreich, U. (1953). Languages in contact, findings and problems, New York: Linguistic Circle of New York.

Weinreich, U. (2011). Languages in contact: French, German and Romansch in twentieth-century Switzerland. Based on Weinreich’s 1951 dissertation at Columbia University. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Yousef, S. (2018). Persian: A comprehensive grammar. London: Routledge.

Acknowledgements

I heartfully thank: my editor at Morphology, Ana Luís, for being patient and for helping me whenever I asked for help; Peter Arkadiev and Alice Idone for carefully reading and commenting on a previous version of this paper; the anonymous reviewers, who had the grace to accept my ‘invites to review’ and did a splendid job; the authors in this special issue for contributing beautiful pieces of scientific production and their hard work. The financial support of the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNF Grant No. CRSII1_160739) is gratefully acknowledged.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Zurich.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gardani, F. Borrowing matter and pattern in morphology. An overview. Morphology 30, 263–282 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-020-09371-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-020-09371-5