Abstract

This paper incorporates morphological markedness constraints into a framework in which morphology and phonology directly interact, modeled with interleaving of morphological and phonological constraints in serial OT (Wolf 2008, 2009). Morphological markedness constraints are constraints against realization (or spell-out) of morphologically marked feature sets. The empirical data motivating this proposal mainly come from the case-study of Russian genitive plural allomorphy, which is analyzed as involving tradeoffs between morphological markedness and other constraints in the grammar, including the purely phonological ones. This proposal explains the otherwise apparently arbitrary and unnatural transderivational dependency between the nominative singular and the genitive plural in Russian. Additionally, this account of the genitive plural allomorphy provides a unified explanation for several seemingly exceptional sub-generalizations which upon examining lexical statistics turn out to be regular. Implications and predictions of an interleaved model with morphological markedness constraints are discussed throughout the article.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

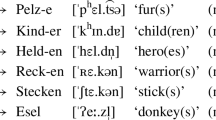

Vowel and consonant alternations seen in these and other examples are due to the processes of vowel reduction and final consonant devoicing. For a discussion of these alternations see Jones and Ward (1969).

While an exceptional behavior (lack of neutralization) in a single cell in a paradigm is not ruled out by any theory that I know of, it is considered to be a deviation from the norm. For example, in the paper “Canonical Inflectional Classes” Corbett puts forth a number of principles that a canonical, unmarked system of inflectional classes must follow (Corbett 2009). Among them is a principle dictating that “forms differ as consistently as possible across inflectional classes, cell by cell,” and that “the existence of shared or default cells gives reduced canonicity” (p. 5). So, the plural paradigm in which five out of six inflectional class distinctions were neutralized (or shared) would be highly marked or non-canonical.

Another stance (similar to a suggestion in Booij 1998) is to handle optimizing allomorphy within OT and non-optimizing allomorphy as subcategorization restrictions.

This term refers to a situation in which a conditioning factor for some allomorph x appears in a morpheme that is derivationally more peripheral to x.

Given the reverse ranking, only part of the restriction is captured, and the grammar predicts that it is possible for a morpheme containing extra features (those that are not in the input) to beat a morpheme that does not contain such extra-features. For example, suppose that the input includes a node with features [nom. masc. pl.], and suppose that the lexicon contains two entries, one specified for Nominative Plural, and one specified for Masculine Singular. The Subset Principle predicts that the first entry should always win. However, if M-Max(masc.) outranked M-Dep(sg.), M-Max(nom), and M-Max(pl), the second entry would win. This might be viewed as problematic because it predicts the existence of languages in which a morpheme specified for Masculine Singular would occur in the Nominative Masculine Plural context. However, the implausibility of such languages can perhaps be explained by implausibility of such competing lexical entries as those assumed above. If, in fact, the same morpheme was used in the nominative masculine plural and a number of masculine singular contexts (as predicted by the above ranking), it is not clear why a learner would ever specify a lexical entry for this morpheme as Masculine Singular. That is, why would a learner decide that a morpheme known to be used in a plural context must be specified as singular? Of course to make this argument more convincing, one would have to work out precisely what the learner does when it learns feature specifications given that the distribution of morphs can depend not only on the lexical items but also on the constraint ranking.

This is consistent with the Jakobsonian assumption that a phonetic Ø can only be an exponent of an unmarked morphological category (Calabrese 2011).

It is possible that the ranking between the two constraints *nom-pl and *gen-sg may be determined on a language specific basis, or according to a feature prominence hierarchy in which Case is considered more important than Number or vice-versa (as suggested in Noyer 1992).

This analysis assumes that the morphological markedness constraints are violated whenever a morphologically marked morpheme (in the syntactic representation) is morphologically realized in the process of lexical insertion. Thus, even if -u is underspecified for case, an output structure in which -u was connected by M-Correspondence to the node ObliqueCase would violate a *OblCase constraint.

Gen-Pl can also be realized syncretically with another cumulative case-number morpheme due to feature underspecification of lexical entries which I do not discuss here.

However, it is entirely possible (and, perhaps, likely) that speakers analyze these nouns as containing the Gen-Pl suffix -/ej/ as in nouns such as [noƷ] – [naƷ-ej] ‘knife, nom.sg.-gen.pl.’

Shapiro (1971) even claims that for some nouns denoting military units different genitive plural allomorphs may be observed depending on whether the noun appears in the collective or individuated context (e.g., polk dragun ‘a regiment of dragoons’), but (e.g., dvux dragun-ov ‘two dragoons’). I did not find support for this claim in my search of the Russian National Corpus.

For example, according to the National Russian Corpus plural forms of the nouns “eye,” “boot,” and “gramm” make up 90 %, 81 %, and 78 % of all inflectional forms of these nouns correspondingly.

There are several examples of such morphological patterning. First, the inflectional class of some nouns depends of the quality of the stem-final consonant. In particular, third declension is comprised of nouns that are feminine and end in a soft consonant. Nouns ending in [ʃ] and [ʒ] also belong to this declension. Second, stems ending in these consonants behave like other soft-stems with respect to triggering the realization of unstressed /o/ as [

] rather than [

] rather than [ ], although admittedly the two reduced versions of this vowel are often hard to distinguish from each other (cf. góst

j-

], although admittedly the two reduced versions of this vowel are often hard to distinguish from each other (cf. góst

j- ,

,  vs. róst-əm). Third, as will be discussed later in this paper, palatalization determines the choice of the overt genitive plural allomorphs. The overt allomorph -/ej/ always follows soft consonants and [ʃ], [ʒ], while the allomorph -/ov/ always follows hard consonants and [j] (which is phonologically soft). It is possible that the exceptional behavior of [j] in this case is due to a dissimilatory process (avoidence of a jVj sequence), but I will not pursue this possibility further.

vs. róst-əm). Third, as will be discussed later in this paper, palatalization determines the choice of the overt genitive plural allomorphs. The overt allomorph -/ej/ always follows soft consonants and [ʃ], [ʒ], while the allomorph -/ov/ always follows hard consonants and [j] (which is phonologically soft). It is possible that the exceptional behavior of [j] in this case is due to a dissimilatory process (avoidence of a jVj sequence), but I will not pursue this possibility further.Two such nouns with -/ov/ could be explained on the grounds that they had stems ending in an illegal Cj cluster.

It is possible that -/ov/ should also be specified as [−fem] since no feminine noun in the lexicon has -/ov/ in the Gen-Pl. Speakers could notice this fact and lexically represent it. However, since my account will not be greatly affected by positing such a feature, I will not pursue this possibility here.

A minority of nouns have further stress alternations within the singular or plural subparadigm. I assume that such nouns are exceptional.

References

Aissen, J. (1999). Markedness and subject choice in optimality theory. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 17, 673–711.

Albright, A. (2007). The many sources of uncertainty: Conflicting vs. insufficient generalizations. In C. Rice & S. Blaho (Eds.), Modeling ungrammaticality in optimality theory. London: Equinox Publishing.

Albright, A. (2008). Inflectional paradigms have bases too: evidence from Yiddish. In A. Bachrach & A. Nevins (Eds.), Inflectional identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Anderson, S. R. (2008). The English “group genitive” is a special clitic. English Linguistics, 25, 1–20.

Arregi, K., & Nevins, A. (2006). Obliteration vs. impoverishment in the Basque g-/z- constraint. In Penn linguistics colloquium special session on distributed morphology (Vol. 30, pp. 1–14).

Artés, E. (2014). Valencian hypocoristics: when morphology meets phonology. In J. Kingston, C. Moore-Cantwell, J. Pater, & R. Staubs (Eds.), Supplemental proceedings of Phonology 2013, LSA.

Baerman, M. (2011). Defectiveness and homophony avoidence. Journal of Linguistics, 47(1), 1–29.

Bailyn, J., & Nevins, A. (2008). Russian genitive plurals are impostors. In A. Bachrach & A. Nevins (Eds.), Inflectional identity (pp. 237–270). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Chap. 8.

Benua, L. (1997). Transderivational identity: Phonological relations between words. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Bermúdez-Otero, R., & Payne, J. (2011). There are no special clitics. In G. H. Alexandra Galani & G. Tsoulas (Eds.), Morphology and its interfaces, Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Blevins, J., & Wedel, A. (2009). Inhibited sound change: an evolutionary approach to lexical competition. Diachronicha, 26(2), 143–183.

Bloomfield, L. (1962). The Menomini language. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Blumenfeld, L. (2002). Russian palatalization and stratal OT. In FASL, Amherst, MA (Vol. 11).

Blumenfeld, L. (2012). Allomorphy happens for a reason (at least sometimes). In Workshop on locality and directionality at the morphosyntax-phonology interface, poster.

Bonet, E. (1991). Morphology after syntax: Pronominal clitics in Romance. PhD thesis, MIT.

Booij, G. (1998). Phonological output constraints in morphology. In W. Kehrein & R. Wiese (Eds.), Phonology and morphology of the Germanic languages (pp. 143–163). Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

Brooks, P. J., Braine, M. D., Catalano, L., & Brody, R. E. (1993). Acquisition of gender-like noun subclasses in an artificial language: The contribution of phonological markers to learning. Journal of Memory and Language, 32(1), 76–95.

Brown, D., & Hippisley, A. R. (1994). Conflict in Russian Genitive plural assignment: a solution represented in DATR. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 2(1), 48–76.

Brunner, J. (2010). Phonological length of number marking morphemes in the framework of typological markedness. In S. Fuchs, P. Hoole, C. Mooshammer, & M. Zygis (Eds.), Between the regular and the particular in speech and language (pp. 5–28). Berlin: Peter Lang.

Bulakhovskii, L. (1952). A course of Russian literary language (5th ed.). Kiev: Radianska shkola.

Burzio, L. (2005). Sources of paradigm uniformity. In L. J. Downing et al. (Eds.), Paradigms in phonological theory (pp. 65–106). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Butska, L. (2002). Faithful stress in paradigms: Nominal inflection in Ukrainian and Russian. PhD thesis, Rutgers University.

Bybee, J. (1998). The emergent lexicon. In Proceedings of the 34th regional meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society: The panels.

Bye, P. (2007). Allomorphy—selection, not optimization. In S. Blaho, P. Bye, & M. Krämer (Eds.), Studies in generative grammar: Vol. 95. Freedom of analysis, Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Chap. 4.

Calabrese, A. (2011). Investigations on markedness, syncretism and zero exponence in morphology. Morphology, 21, 283–325.

Carstairs, A. (1994). Inflection classes, gender, and the principle of contrast. Language, 70, 737–787.

Comrie, B. (1975). Definite and animate direct objects: a natural class. Linguistica Silesiona, 3(13–21).

Corbett, G. (2009). Canonical inflectional classes. In F. Montermini, G. Boyé, & J. Tseng (Eds.), Selected proceedings of the 6th Décembrettes, Cascadilla Proceedings Project, Somerville, MA (pp. 1–11).

Corbett, G., Hippisley, A. R., Brown, D., & Marriott, P. (2001). Frequency, regularity, and the paradigm: a perspective from Russian on a complex relations. In Frequency and the emergence of linguistic structure. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Crosswhite, K. (1999). Intra-paradigmatic homophony avoidance in two dialects of Slavic. In M. K. Gordon (Ed.), UCLA working papers in linguistics, papers in phonology 2 (Vol. 1).

Dimmendaal, G. (1983). The Turkana language. Dordrecht: Foris.

Embick, D. (2010). Localism versus globalism in morphology and phonology. Linguistic inquiry monographs. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Flemming, E. (2002). Auditory representations in phonology. London: Routledge.

Frigo, L., & McDonald, J. (1998). Properties of phonological markers that affect the acquisition of gender-like subclasses. Journal of Memory and Language, 39, 218–235.

Gouskova, M. (2012). Unexceptional segments. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 30(1), 79–133.

Graudina, L. (1964). O nulevoj forme roditel’nogo mnozhestvennogo u sushestvitel’nyx muzhskogo roda. In I. P. Muchnik & M. V. Panov (Eds.), Razvitije grammatiki i leksiki sovremennogo russkogo yazyka (pp. 181–209). Moskva: Nauka.

Greenberg, J. H. (1963). Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements. In J. H. Greenberg (Ed.), Universals of language (pp. 73–113). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Grimshaw, J. (2000). Optimal clitic positions and the lexicon in Romance clitic systems. ROA/000374.

Hall, T., & Scott, J. (2007). Inflectional paradigms have a base: Evidence from s-dissimilation in Southern German dialects. Morphology, 17(1), 151–178. doi:10.1007/s11525-007-9112-z.

Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1993). Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In K. Hale & S. J. Keyser (Eds.), The view from building 20 (pp. 111–176). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Heath, J. (1984). Functional grammar of Nunggubuyu. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Ichimura, L. K. (2006). Anti-homophony blocking and its productivity in transparadigmatic relations. PhD thesis, Boston University.

Iscrulescu, C. (2006). The phonological dimension of grammatical markedness. PhD thesis, University of Southern California.

Ito, J., & Mester, A. (2004). Morphological contrast and merger: ranuki in Japanese. Journal of Japanese Linguistics, 20, 1–18.

Jakobson, R. (1957). The relationship between genitive and plural in the declension of Russian nouns. Scando-Slavica, 3(1), 181–186.

Janda, L. (1996). Back from the brink: a study of how relic forms in languages serve as source material for analogical extension. Lincom Europa.

Jones, D., & Ward, D. (1969). The phonetics of Russian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kager, R. (1999). Optimality theory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kenstowicz, M. (1997). Uniform exponence: Extension and exemplification. In V. Miglio & B. Morén (Eds.), University of Maryland working papers in linguistics, Selected papers from the Hopkins optimality workshop (Vol. 5, pp. 139–154).

Kenstowicz, M. (2005). Paradigmatic uniformity and contrast. In L. Downing, T. A. Hall, & R. Raffelsiefen (Eds.), Paradigms in phonological theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kim, Y. (2010). Phonological and morphological conditions on affix order in Huave. Morphology, 20, 133–163.

Kochetov, A. (2002). Production, perception and emergent phonotactic patterns. New York: Routledge.

Kurisu, K. (2001). The phonology of morpheme realization. PhD thesis, University of California at Santa Cruz, URL http://roa.rutgers.edu/files/490-0102/490-0102-KURISU-0-0.PDF, available as ROA 490-0102.

Kuznetsov, P. (1953). Historical grammar of the Russian language. Morphology. Moscow State University.

López García, A. (1995). Gramática Muisca. LINCOM Europa, München, Newcastle.

Lubowicz, A. (2007). Paradigmatic contrast in Polish. Journal of Slavic Linguistics, 15(2), 229–262.

Manzini, M., & Savoia, L. (2005). I dialetti Italiani e Romanci. Morfosintassi Generativa, Edizioni dell’Orso, Alessandria.

McCarthy, J. (2010). An introduction to Harmonic Serialism. Selected Works.

McCarthy, J. J., & Prince, A. M. (1994). The emergence of the unmarked: Optimality in prosodic morphology. In M. González (Ed.), Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society (Vol. 24, pp. 335–379). Amherst: GLSA.

Müller, G. (2005). A distributed morphology approach to syncretism in Russian noun inflection. In O. Arnaudova (Ed.), FASL (Vol. 12).

Ní Chiosáin, M., & Padgett, J. (2001). Markedness, segment realization, and locality in spreading. In Segmental phonology in optimality theory (pp. 118–156). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Noyer, R. (1992). Features, positions and affixes in autonomous morphological structure. PhD thesis, MIT.

Noyer, R. (1998). Impoverishment theory and morphosyntactic markedness. In D. K. Brentari & P. M. Farrell (Eds.), Morphology and its relation to phonology and syntax (pp. 264–285). Stanford: CSLI.

Noyer, R. (2004). A constraint on interclass syncretism. In G. Booij & J. van Marle (Eds.), Yearbook of morphology, Dordrecht: Springer.

Orgun, C. O., & Sprouse, R. (1999). From mparse to control: deriving ungrammaticality. Phonology, 16, 191–224.

Paster, M. (2005). Subcategorization vs. output optimization in syllable-counting allomorphy. In J. Alderete, C. Hye Han, & A. Kochetov (Eds.), Proceedings of the twenty-fourth West Coast conference on formal linguistics (pp. 326–333).

Payne, J. (2009). The English genitive and double case. Transactions of the Philological Society, 107(3), 322–357.

Pertsova, K. (2004). Distribution of genitive plural allomorphs in the Russian lexicon and in the internal grammar of native speakers, Ma thesis, UCLA.

Pertsova, K. (2014). Morphological markedness in an ot-grammar: zeros and syncretism. In J. Kingston, C. Moore-Cantwell, J. Pater, & R. Staubs (Eds.), Supplemental proceedings of phonology 2013, Washington: Linguistic Society of America.

Popova, T. V. (1987). Morphonologičeskie tipy substantivnyx paradigm v sovremennom russkom literaturnom jazyke. In T. V. Popova (Ed.), Slavyanskaya morfonologija (pp. 16–37). Moskva: Nauka.

Prince, A., & Smolensky, P. (1993). Optimality theory: Constraint interaction in generative grammar. RuCCS-TR-2 ROA-537, Rutgers University.

Rebrus, P., & Törkenczy, M. (2005). Uniformity and contrast in the Hungarian verbal paradigm. In L. Downing, T. A. Hall, & R. Raffelsiefen (Eds.), Paradigms in phonological theory, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Shvedova, N. (1980). Russian grammar. Moskva: Nauka. Academy of Sciences USSR, The Institute of the Russian Language.

Shapiro, M. (1971). The genitive plural desinenses of the Russian substantive. The Slavic and East European Journal, 15(2), 190.

Sharoff, S. (1998). The frequency dictionary for Russian. http://bokrcorpora.narod.ru/frqlist/frqlist-en.html.

Silverstein, M. (1976). Hierarchy of features and ergativity. In R. Dixon (Ed.), Grammatical categories in Australian languages (pp. 112–171). New Jersey: Humanities Press.

Starostin, S. (1998). Zaliznyak’s on-line dictionary. http://starling.rinet.ru/cgi-bin/main.cgi?flags=eygtmnl, An Etymological database project.

Steriade, D. (1999). Lexical conservatism in French adjectival liason. In M. Authier, B. Bullock, & L. Reed (Eds.), Proceedings of the 25th linguistic colloquium on Romance languages. Amsterdam: John Benjamnins.

Steriade, D. (2008). A pseudo-cyclic effect in Romanian morpho-phonology. In A. Bachrach & A. Nevins (Eds.), Oxford studies in theoretical linguistics: Vol. 18. Inflectional identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sturgeon, A. (2003). Paradigm uniformity: Evidence for inflectional bases. In G. Garding & M. Tsujimura (Eds.), WCCFL (Vol. 22, pp. 464–476).

Teeple, D. (2008). Lexical selection and strong parallelism. ROA archive 000992.

Urbanczyk, S. (1999). A-templatic reduplication in Halq’emeylem. In Proceedings of the West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (pp. 655–669).

Walker, R., & Feng, B. (2004). A ternary model of morphology-phonology correspondence. In Proceedings of WCCFL 23 (Vol. 23, pp. 773–786).

Weinert, S. (2009). Implicit and explicit modes of learning: similarities and differences from a developmental perspective. Linguistics, 47(2), 241–271.

Wolf, M. A. (2008). Optimal interleaving: serial phonology-morphology interaction in a constraint-based model. PhD thesis, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Wolf, M. A. (2009). Lexical insertion occurs in the phonological component. In E. Bonet, M.-R. Lloret, & J. Mascaró (Eds.), Understanding allomorphy: perspectives from optimality theory. London: Equinox Publishing.

Yang, C., Gorman, K., Preys, J., & Borwczyk, M. (2012). Productivity and paradigmatic gaps, a talk presented at NELS, 43.

Yanovich, I., & Steriade, D. (2010). Uniformity, subparadigm precedence and contrast derive stress patterns in Ukrainian nominal paradigms, talk at OCP 6.

Yearley, J. (1995). Jer vowels in Russian. In J. L. Beckman, L. W. Dickey, & S. Urbanczyk (Eds.), Papers in optimality theory (pp. 533–571). Amherst: GLSA.

Zipf, G. (1932). Selective studies and the principle of relative frequency in language. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the following people for useful discussion and feedback at various stages of this project: Adam Albright, Donca Steriade, Elliott Moreton, Jennifer Smith, Laura Janda, Tore Nesset, and the anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pertsova, K. Interaction of morphological and phonological markedness in Russian genitive plural allomorphy. Morphology 25, 229–266 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-015-9256-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-015-9256-1

] rather than [

] rather than [ ], although admittedly the two reduced versions of this vowel are often hard to distinguish from each other (cf. góst

j-

], although admittedly the two reduced versions of this vowel are often hard to distinguish from each other (cf. góst

j- ,

,  vs. róst-əm). Third, as will be discussed later in this paper, palatalization determines the choice of the overt genitive plural allomorphs. The overt allomorph -/ej/ always follows soft consonants and [ʃ], [ʒ], while the allomorph -/ov/ always follows hard consonants and [j] (which is phonologically soft). It is possible that the exceptional behavior of [j] in this case is due to a dissimilatory process (avoidence of a jVj sequence), but I will not pursue this possibility further.

vs. róst-əm). Third, as will be discussed later in this paper, palatalization determines the choice of the overt genitive plural allomorphs. The overt allomorph -/ej/ always follows soft consonants and [ʃ], [ʒ], while the allomorph -/ov/ always follows hard consonants and [j] (which is phonologically soft). It is possible that the exceptional behavior of [j] in this case is due to a dissimilatory process (avoidence of a jVj sequence), but I will not pursue this possibility further.