Abstract

The feminine suffixes -at, -et, -it, -ut, -ot of Modern Hebrew are regularly treated as morphologically simplex. In this paper, I argue for the decomposition of -it and -ut into -i-t and -u-t on the basis of semantic, phonological and morphological evidence. The paper has two parts. In the first part, the data and the main claims are presented. The feminine suffix is defined as -t. The distribution and function of -i- and -u- in the feminine suffixes are defined, and both -i- and -u- are shown to carry similar functions elsewhere in the language, without the feminine -t. A novel analysis of the plural analysis is also presented. The second part is an application to the data of Lowenstamm’s (Derivational affixes as roots (phasal spellout meets English stress shift). Ms., LLF, 2010, to appear) specific view of Distributed Morphology (Halle and Marantz in The view from building 20, pp. 111–176. MIT Press, Cambridge, 1993). Through this formal analysis, -i- is shown to be a structurally expletive morpheme. The morpheme -u- is analyzed as its [-concrete] alternant. The latter is shown to appear in both concatenative and non-concatenative suffixes, thus illustrating an understudied possible consequence of the non-concatenative nature of Semitic morphology. The framework adopted—the version of Distributed Morphology in Lowenstamm (Roots, Oxford University Publishing, to appear)—receives support in the success of the analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Harbour (2009), which also argues for the traditional view that -t is feminine, classifies [a] as an epenthetic vowel. However, the epenthetic vowels of either Biblical or Modern Hebrew are not [a]—they are [ə/ĭ] and [e] respectively. It is thus best to treat the [a] of -at as a default realization.

Some of the items that belong to the first group (6a) denote entities that are smaller than those denoted by the base, e.g. the second example in (6a) or mapuax ‘bellows’ vs. mapuxit ‘harmonica’. As the last example shows, this is not the evaluative morphology of diminutives, since the entity denoted is not just a small version of the base (moreover, MH has a productive diminutive suffix -on, f.. -ón-et). Furthermore, there are also many cases of base + it where the entity derived is not smaller, but rather more concrete than the base, e.g. the first example in (6a) or xašmal ‘electricity’ xašmal-it ‘tram’. The definition in the text, namely “the derivation of new content-words on the basis of existing ones” is thus the most adequate. The concreteness effect will become clear in the next subsection, when -it is compared to -ut.

These bases, whose masculine version usually bears agentive meaning, have a stable prosody when suffixed (sapar-saparim ‘barber (sg.-pl.)’). Stable QaTaL contrasts with unstable QaTaL, which does not have this meaning, and whose first vowel syncopates upon suffixation (gamal-gmalim ‘camel (sg.-pl.)’).

A reviewer notes that the theory adopted later in this paper, namely Distributed Morphology (DM, Halle and Marantz 1993), does not recognize the existence of paradigms as a linguistic object. This view undermines the claim that there is a difference between the relation yarkan–yarkan-it ‘vegetable vendor (m.–f.)’ and medaber–medabér-et ‘speak.part.(m.–f.)’, whereby the latter stand in a paradigmatic relation but the former do not. I do not think that rejection of paradigms is obligatorily inherent to DM, rather than an opinion of some of its proponents. That said, the distinction can also be reformulated in terms of inherent vs. agreement features: but developing such an analysis would require an entire paper. Moreover, the claim that forms ending in the agentive suffixes are not templatic is supported by the concatenative behavior of these affixes (see (6b) for examples).

Most existing nouns in QTuLa are collective (even more so if we include the template tQuLa in this account, e.g. tmuta ‘mortality’, tnu’a ‘traffic, movement’). There are a few items in QTuLa that escape this generalization (cf. glula ‘pill’), which may have a different derivational history. Furthermore, although this template is only marginally productive, its only productive function is the creation of collective nouns.

The assumption here is that /u/ is a thematic vowel of QóTeL; the parallel template QéTeL, without the round vowel, cannot be said to host [-concrete] nouns in the same manner or to the same extent.

In fact, the word béger does appear in the list of Hebrew words in Avineri (1976).

The sequence [QTuya] is possible in Hebrew, but it is found only in feminine counterparts of the passive participle [QaTuy], e.g. šatuy–štuya ‘drunk (m.–f.)’. Besides this systematic exception, I found one exception to the generalization concerning the absence of QTuya, namely gluya ‘postcard’. This noun could be analyzed as a nominalization of the feminine passive participle gluya ‘exposed(f.)’.

The analysis of -i as pointing to a derived status is corroborated by the complete absence of templatic activity related to -i. Unlike other suffixes in MH, such as -an, the attachment of -i never imposes any consistent sound changes on its base. This, as claimed here and developed in the analysis in Sect. 3, follows from its distribution, on top of n/a/vP. In this respect, one objection to the analysis in the body of the paper may mention such rare examples as rišm-i ‘official’, which does not have any apparent base. However, besides being very rare, such examples do not form a consistent group, and moreover can be analyzed as -i attached to a potentially-existing word: compare rišmi above to šivti ‘tribal’ (<ševet ‘tribe’). One reviewer notes that the switch in the form of the base from QéTeL to QiTL- might constitute templatic behavior. While that is true, this templatic behavior is independent of the suffix -i and is true whenever such bases carry vowel-initial suffixes, e.g. šivt-o ‘his tribe’, šivt-on ‘tribe (dim.)’, šivt-ey ‘tribes of’ etc.

The paper is the official version of Lowenstamm (2010), available on the author’s website.

This is a technical implementation of the more general idea that affixes may select their complements, already present in Selkirk (1982).

In DM, stems are not a level of representation, and constitute the mere residue of the subtraction of concatenative affixes.

Non-templatic words whose roots are not triradical do exist in MH, e.g. tíras ‘corn’.

Attributing features such as [gender] to roots is potentially problematic, since [gender] implies nominal status, and roots in DM are not regarded as carrying information about their category. The [gender] feature in this case can be conceptualized as a listed fact about the direct merger of a head noun and roots such as √kos. Of course, the details of this possible solution deserve a much more elaborate discussion than it is possible to provide in the present context.

In Faust (2011), which develops this analysis, this position is taken to be [spec, √P].

A reviewer asks why it is impossible for the feminine of templatic QaTiL to be built on the nP level of the masculine, thus predicting unattested *QTiLit. I suspect that this is due to a general preference for templatic realization over concatenative realization, at least when there is a templatic feminine form and the template is productive. This preference can be paralleled to the preference for listed allomorphs like feet over the non-lexical -s.

For instance, the positioning of -u- within the different items is treated.

That the basis of QTuLa is QaTuL can be seen in items whose first consonant is a historical guttural, which maintain the /a/ in this position, e.g. (ʔ)atuda ‘reserve (forces)’. Historical gutturals were never recovered in MH, and the epenthetic vowel of the language in [e]; so synchronically, the vowel /a/ must be underlyingly present in QTuLa nouns, too. As mentioned before (4) in the main text, this vowel often disappears when it is not pretonic.

Of course, the claim was not that any occurrence of -i in the language is expletive.

References

Arad, M. (2005). Roots and patterns: Hebrew morphosyntax. Dordrecht: Springer.

Aronoff, M. (1994). Linguistic inquiry monographs: Vol. 22. Morphology by itself: stems and inflectional classes. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Avineri, I. (1976). Hexal Hamiškalim. Tel Aviv: Izre’el.

Bat-El, O. (1989). Phonology and word structure in modern Hebrew. PhD dissertation, UCLA.

Bat-El, O. (1994). Stem modification and cluster transfer in Modern Hebrew. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory, 12(4), 571–596.

Bat-El, O. (1997). On the visibility of word internal morphological features. Linguistics, 35, 289–316.

Bolozky, S., & Schwarzwald, O. R. (1992). On the derivation of Hebrew forms with the +ut suffix. Hebrew Studies, 33, 51–69.

De Belder, M., Faust, N., & Lampitelli, N. (to appear). On a inflectional and a derivational diminutive. In A. Alexiadou, H. Borer, & F. Schäfer (Eds.), The syntax of roots and the roots of syntax. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Doron, E. (2003). Agency and voice: the semantics of the Semitic template. Natural Language Semantics, 11, 1–67.

Faust, N. (2011). Forme et fonction dans la morphologie nominale de l’hébreu moderne. Etudes en morpho-syntaxe. Ph.D. dissertation, Université Paris Diderot-Paris 7.

Faust, N. (to appear). The alternations between [a], [e] and ø in Modern Hebrew nouns: phonological and morpho-syntactic implications. Brill’s Annual of Afro-Asiatic Language and Linguistics.

Faust, N. (in prep.). Matters of state: Modern Hebrew number and state allomorphies.

Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1993). Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In K. Hale & S. J. Keyser (Eds.), The view from building 20 (pp. 111–176). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Harbour, D. (2009). On homophony and methodology in morphology. Morphology, 18, 75–92.

Kihm, A. (2001). Agreement in noun phrases in Semitic: its nature and some consequences for morphosyntactic representations. Ms., Laboratoire de Linguistique Formelle.

Lowenstamm, J. (1996). CV as the only syllable type. In J. Durand & B. Laks (Eds.), Current trends in phonology. Models and methods (pp. 419–441). Salford: ESRI.

Lowenstamm, J. (2010). Derivational affixes as roots (phasal spellout meets English stress shift). Ms., LLF.

Lowenstamm, J. (2011). The phonological pattern of phi-features in the perfective paradigm of Moroccan Arabic. Ms., LLF.

Lowenstamm, J. (2012). Feminine and gender, or why the feminine profile of French nouns has nothing to do with gender. In E. Cyran, H. Kardela, & B. Szymanek (Eds.), Linguistic inspirations. Edmund Gussmann in memoriam (pp. 371–406). Lublin: Wydawnictwo Katolicki Uniwersytet Lubelski.

Lowenstamm, J. (to appear). Derivational affixes as roots, no exponence (phasal spellout meets English stress shift). In Roots. Oxford University Publishing.

Marantz, A. (2007). Phases and words. In S.-H. Choe (Ed.), Phases in the theory of grammar (pp. 196–226). Seoul: Dong-in

Melčuk, I., & Podolsky, B. (1996). Stress in modern Hebrew nominal inflection. Theoretical Linguistics, 22, 155–194.

Scheer, T. (2004). What is CVCV, and why should it be?: Vol. 1. A lateral theory of phonology. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Schwarzwald, O. R. (2002). Studies in Hebrew morphology, Vol. 1–4. Tel Aviv: Open University Press (in Hebrew).

Selkirk, E. O. (1982). The syntax of words. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: The phonology of complex feminine suffixes

Appendix: The phonology of complex feminine suffixes

This appendix discusses the phonological and morpho-phonological aspects of the feminine suffixes of MH. The analysis is couched within the CVCV option of Government Phonology, where the skeletal tier is composed of strictly alternating CV units (Lowenstamm 1996; Scheer 2004). I will be concerned with two aspects of the data: the floating of the feminine /t/ only in the suffix -at and the interaction between the vowels of the suffixes.

The suffix /-at/, when its vowel is realized as [a], only reveals the underlying consonant /t/ in the Construct State. It is the only one of the five feminine suffixes to exhibit this behavior. In Sect. 2.1, this property was analyzed as due to insufficient skeletal support: given two CV units, if the vowel [a] is analyzed as occupying both V-slots (i.e. being long), then the /t/ must remain afloat. But why is it that only /at/—only the singular expression of the feminine √at when its complement is a root—exhibits this behavior?

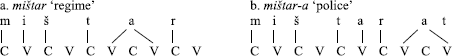

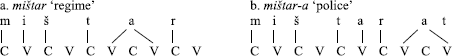

In Faust (2011, to appear), I develop the idea that /at/ is skeletally parasitic: its underlying representation does not have its own skeleton, and the suffix must dock onto the skeleton of its base. Consider a pair of nouns such as mištar ‘regime’ vs. mištar-a ‘police’. The masculine noun is represented in (33b): the last, stressed vowel is long, and the template thus occupies five CV units. The feminine noun, represented in (33b), occupies the same number of CV units: if the vowel of the suffix is to be realized as long, the last vowel of the base comes to occupy only one slot. Pretonic vowels in open syllables in MH, even though they are linked to one position, maintain their quality.

-

(33)

/at/ is parasitic on the skeleton of its base

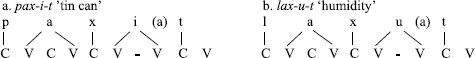

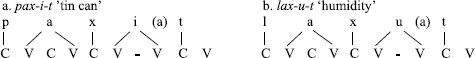

As claimed in the body of the paper, -it and -ut are complex. In order to account for the non-floating of the /t/ in their case, all one must assume is that the morphemes √i and √u, unlike √at, do have their own skeleton. In (34), they are both accompanied by two CV units. Thus when they are added to bases such as pax ‘tin’ and lax ‘humid’ (34a,b), the resulting words will have enough space for the feminine /t/ to land. Recall the /a/ is no longer part of the realization in these cases; that said, the disappearance of /a/ from these representations could be interpreted as a result of lack of templatic support.

-

(34)

Additional skeletal space provided by √i and √u

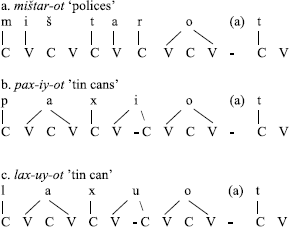

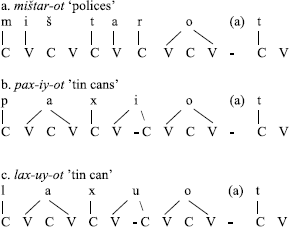

Accordingly, one may claim the same thing for the feminine plural. The root √o, which was claimed to be inserted next to √at when the head num carries a feature [plural], can further be claimed to supply the additional CV unit, needed for the linking of the /t/. This is shown for the plurals of mištara ‘police’, paxit ‘tin can’ and laxut ‘humidity’, in (35a–c). In all three cases portrayed, the plural form has exactly one CV unit more than the singulars in (33) and (34). In all three, the vowel /o/ is long and attracts stress. In (35a), the /o/ completely replaces the /a/ of the singular; in (35b,c), the -i- and -u- are “shoved” by the long /o/ and link to the intervening C-slot. That a glide [y] should surface is therefore unsurprising, at least for -i-; for -u-, the surfacing of the same glide can be regarded as the result of the lack of [w] in MH.

-

(35)

Plural √o contributes a CV slot

Of course, there are other linking patterns possible given these segments and this number of CV units. This appendix should not understood as claiming that the linking pattern is completely predictable; at least some aspects of it could be morpho-phonological, that is, fixed for the interaction of these specific morphemes.

In this Appendix, I have shown an autosegmental analysis of the phonology of feminine suffixes. It was proposed that certain suffixes contain a specific number of CV units in their underlying representation, while others do not, and are therefore parasitic on the skeleton of their base. This assumption was used to account for the floating pattern of /t/ and for the appearance of certain glides. The inclusion or exclusion of /a/ from the realization may also be explained in this manner.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Faust, N. Decomposing the feminine suffixes of Modern Hebrew: a morpho-syntactic analysis. Morphology 23, 409–440 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-013-9230-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-013-9230-8