Abstract

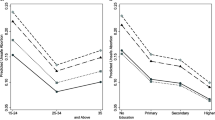

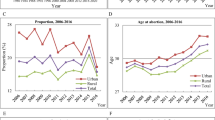

This study aims to describe trends in inequalities by women’s socioeconomic position and age in induced abortion in Barcelona (Spain) over 1992–1996 and 2000–2004. Induced abortions occurring in residents in Barcelona aged 20 and 44 years in the study period are included. Variables are age, educational level, and time periods. Induced abortion rates per 1,000 women and absolute differences for educational level, age, and time period are calculated. Poisson regression models are fitted to obtain the relative risk (RR) for trends. Induced abortion rates increased from 10.1 to 14.6 per 1,000 women aged 20–44 (RR = 1.44; 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.41–1.47) between 1992–1996 and 2000–2004. The abortion rate was highest among women aged 20–24 and 25–34 and changed little among women aged 35–44. Among women aged 20–24 and 25–34, those with a primary education or less had higher rates of induced abortion in the second period. Induced abortion rates also grew in those women with secondary education. In the 35–44 age group, the induced abortion rate declined among women with a secondary education (RR = 0.66; 95% CI 0.60–0.73) and slightly among those with a greater level of education. Induced abortion is rising most among women in poor socioeconomic positions. This study reveals deep inequalities in induced abortion in Barcelona, Spain. The trends identified in this study suggest that policy efforts to reduce unintended pregnancies are failing in Spain. Our study fills an important gap in literature on recent trends in Southern Europe.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Peiro R, Colomer C, Alvarez-Dardet C, Ashton JR. Does the liberalization of abortion laws increase the number of abortions? The case study of Spain. Eur J Public Health. 2001; 11(2): 190-194.

Ministerio de Sanidad y Consumo. Interrupción Voluntaria del Embarazo Datos definitivos correspondientes al año 2006 [Pregnancy interruption of 2006]. Available at: http://www.msc.es/profesionales/saludPublica/prevPromocion/docs/IVE_2006.pdf. Accessed 20 November 2008.

Henshaw SK, Singh S, Hass T. Recent trends in abortion rates worldwide. Int Fam Planning Perspect. 1999; 25: 44-48.

Sendgh G, Henshaw SK, Singh S, Bankole A, Drescher J. Legal abortion worldwide: incidence rate and recent trends. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2007; 33: 106-116.

Agència de Salut Pública. La salut a Barcelona, 2007 [Health in Barcelona, 2007]. Available at: http://www.aspb.cat/quefem/documents_informes_salut_barcelona.htm. Accessed 20 November 2008.

Font-Ribera L, Pérez G, Salvador J, Borrell C. Socioeconomic inequalities in unintended pregnancy and abortion decision. J Urban Health. 2008; 85: 125-135.

Kero A, Hogberg U, Jacobsson L, Lalos A. Legal abortion: a painful necessity. Soc Sci Med. 2001; 53: 1481-1490.

Raleigh VS. Abortion rates in England in 1995: comparative study of data from district health authorities. BMJ. 1988; 316: 1711-1712.

Helström L, Zättersröm C, Odlind V. Abortion rate and contraceptive practices in immigrant and Swedish adolescents. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2006; 19(3): 209-213.

Besculides M, Laraque F. Unintended pregnancy among the urban poor women. J Urban Health. 2004; 81: 340-348.

Galobardes B, Shaw M, Lawlor DA, Lynch JW, Smith GD. Indicators of socioeconomic position (part1). J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006; 60: 7-12.

Valero C, Nebot M, Villalbi JR. Embarazo adolescente en Barcelona: su distribución, antecedentes y consecuencias.[Adolescent pregnancy in Barcelona: its distribution, antecedents and consequences]. Gac Sanit. 1994; 8(43): 155-161.

Cano-Serral G, Rodriguez-Sanz M, Borrell C, del Pérez MM, Salvador J. Desigualdades socioeconómicas relaciondas con el cuidado y el control del embarazo [Socioeconomic inequalities in the provision and uptake of prenatal care]. Gac Sanit. 2006; 20: 25-30.

Salvador J, Cano-Serral G, Rodriguez-Sanz M, et al. Evolución de las desigualdades según la clase social en el control del embarazo en Barcelona (1994–97 frente a 2000–03) [Trends in social inequalities in pregnancy care in Barcelona (Spain), 1994–97 versus 2000–03.]. Gac Sanit. 2007; 21: 378-383.

StataCorp. Stata statistical software: release 9. College Station: StataCorp Lp; 2005.

Marston C, Cleland J. Relationships between contraception and abortion: a review of the evidence. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2003; 29: 6-13.

Hassani KF, Kosunen E, Rimpelä A. The use of oral contraceptives among Finnish teenagers from 1981 to 2003. J Adolescent Health. 2006; 39: 649-655.

Skouby SO. Contraceptive use and behavior in the 21st century: a comprehensive study across five European countries. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2004; 9: 57-68.

Alan Guttmacher Institute. Sharing responsibility women, society and abortion worldwide. Report, Alan Guttmacher Institute 1999. Available at: http://www.guttmacher.org/pubs/sharing.pdf. Accessed 20 October 2008.

Asociación Salud y Familia. Programme of safe motherhood assistance. (2006). Available at: http://www.saludyfamilia.es/downloads/Memoria%20IVE%202006%20Cast.pdf. Accessed 14 March 2008.

Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield-Timachy K, et al. The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003; 35: 94-101.

De Sanjose S, Cortés X, Méndez C, et al. Age at sexual initiation and number of sexual partners in the female Spanish population. Results from the AFRODITA survey. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008; 140: 234-240.

Smith T. Influence of socio-economic factors on attaining targets for reducing teenage pregnancies. BMJ. 1993; 306(6887): 1232-1235.

Uria M, Mosquera C. Legal abortion in Asturias (Spain) after the 1985 law: sociodemographic characteristics of women applying for abortion. Eur J Epidemiol. 1990; 15: 59-64.

American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on adolescence. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics. 2005; 116(4): 1026-1035.

Jackson R, Schwarz E, Freedman L, Darney P. Knowledge and willingness to use emergency contraception among low-income post-partum women. Contraception. 2000; 61: 351-357.

Barcelona City Council. Demografia i població [Demography and population]. Available at: http://www.bcn.cat/estadistica/catala/dades/anuari/cap02/C0201090.htm. Accessed 14 March 2008.

Finer LB, Henshaw SK. Disparities in rates of unintended pregnancy in the United States, 1994 and 2001. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2006; 38: 90-96.

Krieger N, Williams DR, Moss NE. Measuring social class in US public health research: concepts, methodologies and guidelines. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997; 18: 341-378.

Domingo-Salvany A, Regidor E, Alonso J, Alvarez-Dardet C. Proposal for a social class measure. Working group of the Spanish Society of epidemiology and the Spanish society of family and community medicine. Aten Primaria. 2000; 25(5): 350-363.

Mason KO. The status of women: a review of its relationships to fertility and mortality. New York: The Rockefeller Foundation; 1984.

Murphy A, Creinin MD. Pharmacoeconomics of medical abortion: a review of cost in the United States, Europe and Asia. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003; 4(4): 503-513.

Kunst AE, Bos V, Andersen O, et al. Monitoring of trends in socioeconomic inequalities in mortality. Demographic Research Special Collections. 2004; 2(9): 229-254.

Cambronero-Saiz B, Ruiz Cantero T, Vives-Cases C, Carrasco Portiño M. Abortion in democratic Spain: the parliamentary political agenda 1979–2004. Reprod Health Matters. 2007; 15: 1-12.

Acknowledgements

We thank Roser Bosser and Rosa Gispert from the Health Department and Birgit Ferran and Dave McFarlane for their help in editing the manuscript.

Funding

This study was partially funded by the Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (project number PI052618) Ministry of Health and by the Network of Biomedical Investigation of Epidemiology and Public Health of Spain (CIBERESP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pérez, G., García-Subirats, I., Rodríguez-Sanz, M. et al. Trends in Inequalities in Induced Abortion According to Educational Level among Urban Women. J Urban Health 87, 524–530 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-009-9394-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-009-9394-z