Abstract

Background

Cabozantinib has recently been evaluated as a first-line treatment in advanced renal cell carcinoma (aRCC).

Objective

To indirectly assess efficacy of cabozantinib versus standard-of-care (SoC) comparators in the first-line treatment of aRCC.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) to identify randomized controlled studies in the first-line setting for aRCC. The outcomes analyzed were overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS). A network meta-analysis (NMA) was conducted comparing OS and PFS hazard ratios (HRs).

Results

Thirteen studies were identified in the SLR to be eligible for inclusion in the NMA. The overall study populations were heterogeneous in terms of risk groups; some studies included favorable risk patients. In intermediate-risk patients, HRs (95% confidence interval) for PFS were 0.52 (0.33, 0.82), 0.46 (0.26, 0.80), 0.20 (0.12, 0.36), and 0.37 (0.20, 0.68) when cabozantinib was compared with sunitinib, sorafenib, interferon (IFN), or bevacizumab plus IFN, respectively. In poor-risk patients, the NMA also demonstrated significant superiority in terms of PFS for cabozantinib; HRs were 0.31 (0.11, 0.90), 0.22 (0.06, 0.87), 0.16 (0.04, 0.64), and 0.20 (0.05, 0.88), when cabozantinib was compared with sunitinib, temsirolimus, IFN, or bevacizumab plus IFN, respectively. When the overall study populations were compared, the results were similar to the subgroup analyses. OS HRs in all analyses favored cabozantinib, but were not statistically significant.

Conclusions

The results suggest that cabozantinib significantly increases PFS in intermediate-, and poor-risk subgroups when compared to standard-of-care comparators. Although overall populations included favorable risk patients in some studies, the results seen were consistent with the subgroup analyses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common type of kidney cancer and accounts for 2–3% of cancers worldwide [1]. The incidence is highest among men (twice over women’s rate [2]) and is increasing in many countries [3]. Individuals affected by RCC are often asymptomatic, and approximately 25–30% of patients have metastatic or advanced RCC (aRCC) at time of diagnosis [4], usually indicating a poor prognosis [5]. Prognostic factors have been identified by both the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) [5] and the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) [6]. IMDC and MSKCC criteria overlap, and the majority of patients are categorized into the same risk group using either set of criteria [7]. The criteria are used to classify patients into three risk groups (i.e., favorable, intermediate, and poor), which can aid in establishing a prognosis and guiding treatment choice. For poor- and intermediate-risk patients, median OS is 7.8 months and 22.5 months respectively, compared with 43.2 months for those with favorable risk [7]. In the real-world setting, median OS is 20.9 months for patients receiving first-line targeted therapy for metastatic RCC, and 14.7 months for those with intermediate/poor risk [8].

The introduction of targeted therapies during the past decade has improved survival outcomes for patients diagnosed with aRCC. These treatment options include agents that target the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway (e.g., sunitinib, bevacizumab, pazopanib, axitinib) or the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway (e.g., temsirolimus, everolimus [9]). According to the European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) Clinical Practice Guidelines, the standards of care for first-line treatment of aRCC patients with good or intermediate prognosis are bevacizumab (combined with interferon [IFN]), sunitinib, and pazopanib. The efficacy of both sunitinib and pazopanib has been confirmed by real-world evidence studies [10], and these two agents are currently the most commonly used first-line treatments for aRCC [11]. Alternatively, high-dose interleukin-2 (IL-2), sorafenib, and low-dose IFN combined with bevacizumab may be considered as first-line treatment options. For patients with poor prognosis, the standard first-line treatment choice is temsirolimus, with options to use sunitinib, sorafenib, or pazopanib [11].

Cabozantinib constitutes a newer first-line treatment option for patients with aRCC. It is an oral small-molecule inhibitor of multiple tyrosine kinases, including vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR2), MET (receptor tyrosine kinase for hepatocyte growth factor), and AXL (receptor tyrosine kinase for GAS6) [12]. Cabozantinib was previously approved for second-line treatment of patients with aRCC. Recently, an investigator-initiated, randomized phase II multicenter trial (CABOSUN) compared cabozantinib with sunitinib as first-line therapy in patients with aRCC. This trial demonstrated that in patients with intermediate- or poor-risk aRCC, first-line treatment with cabozantinib resulted in significantly increased PFS (median 8.6 vs 5.3 months) over the current standard of care (sunitinib) [13]. In December 2017, following priority review, the Food and Drug Administration granted approval to cabozantinib for first-line treatment of patients with aRCC based on CABOSUN study. In Europe, cabozantinib is currently being evaluated as a first-line treatment in aRCC by the European Medicine Agency.

Given the variety of treatment standards in various countries, there is a need to compare the efficacy and safety of all available treatment options. However, head-to-head clinical trials are usually not available as a basis for treatment decisions, and it is not feasible to conduct head-to-head evaluations of all therapeutic options. To generate indirect evidence of comparative efficacy that can be used to support treatment decisions for this patient population, we therefore carried out a systematic review of the available randomized controlled trials for first-line aRCC treatments and conducted a comprehensive network meta-analysis (NMA) comparing the efficacy of the agent, cabozantinib, with standard-of-care treatments currently approved in Europe.

2 Methods

2.1 Search Methods

Our NMA was based on studies identified through a systematic literature review (SLR) conducted in June 2017. A comprehensive search protocol was developed (see Supplementary Information). The search strategy combined an existing published literature review with supplemental searches. The pazopanib manufacturer NICE submission document comprised a systematic review on pazopanib, bevacizumab plus IFN, IFN, IL-2, sunitinib, sorafenib, and temsirolimus for the period 1980–2009. A supplemental search was conducted for these treatments to fill the gap for the period 2009–2017, and for cabozantinib and tivozanib (which were not part of the pazopanib report) for the entire period from 1980 to 2017 using the MEDLINE®, Embase, and Cochrane databases. Additionally, records were identified through search of a clinical trial study registry (clinicaltrials.gov). References of identified systematic reviews, HTA, meta-analyses, and indirect treatment comparisons (ITC) were checked to identify any additional records.

2.2 Selection Criteria

The SLR followed the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcomes) framework and, in brief, utilized the following selection criteria (see supplementary material for full criteria). The population included adult patients ≥ 18 years of age with previously untreated aRCC. The treatments included the following in the first-line setting: cabozantinib (Cabometyx™), sunitinib (Sutent®), pazopanib (Votrient®), interferon alfa (Intron® A, Roferon®-A); interleukin-2 (Proleukin®), sorafenib (Nexavar®), bevacizumab (Avastin®) plus interferon alfa, temsirolimus (Torisel®), and tivozanib (Fotivda®). Comparators included any interventions from the above list, placebo, or best supportive care (BSC). Target outcomes were OS and PFS. Study designs eligible for inclusion were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and letters reporting RCTs. We included SLRs, meta-analyses, and HTAs for screening of bibliographies. Studies published in English, French, German, Italian, and Spanish were included. Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and excluded records that did not meet the selection criteria. Both reviewers then evaluated full-text articles for inclusion in the SLR, and resolved discrepancies through discussion or reconciliation by a third reviewer.

2.3 Data Extraction

One reviewer extracted data from eligible studies, and a second, independent reviewer assessed all extracted data. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus. Extracted data included the following: study design variables, patient characteristics, risk categories, efficacy outcomes for median PFS and OS (in months), and HRs. For studies that had more than two arms with available HRs, only the treatments of interest were included. If a single study had more than one publication for the same outcome, the most recently reported data were selected. The preferred PFS endpoint was that determined by an independent review committee (IRC). If not available, investigator-determined PFS was used instead. Adjusted/stratified HRs for OS were preferred over non-adjusted/unstratified HRs. Finally, two independent reviewers critically appraised all eligible studies using assessment criteria based on recommendations in the NICE manufacturer’s template.

2.4 Statistical Analysis

The NMA was performed based on HRs of two efficacy endpoints in three patient groups: OS and PFS in the overall patient population and intermediate- and poor-risk sub-groups (network diagrams are available in the Supplementary Information; Figs. A-1– A-6). In order to assess potential differences among the study populations, baseline patient characteristics in the identified studies were compared. The NMA was executed in R 3.2.3 using package netmeta to perform frequentist maximum likelihood estimation [14]. The model was a fixed-effect model based on logarithms of HRs, as previously described for example in Caldwell et al. 2005 and Rücker et al. 2012 [15, 16], yielding linear regression models where the parameters to estimate were log(HRs) between any treatment and the reference treatment (cabozantinib). The model can be summarized as follows:

where θ′ is a vector of observed log(HRs) between pairs of treatments, θ is a vector of treatment effects to estimate, X is a design matrix for pairwise comparisons of treatments and comparators, and Σ is a diagonal matrix of inverse variances of each of the log(HR) estimates. Model outputs are point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for HRs between pairs of treatments, herein summarized as forest plots for the PFS and OS outcomes. The HRs were calculated for cabozantinib versus other treatments.

3 Results

3.1 Study Selection

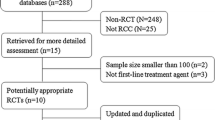

Eighty-eight references were identified through the bibliography of the pazopanib manufacturer submission document for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) [17]. The systematic literature search in bibliographic databases yielded 5094 citations, and additional records were identified with searches of the clinicaltrials.gov registry (n = 41). After removal of duplicates, 4115 abstracts were screened and 3625 were excluded at this stage. After full-text screening, an additional 388 publications were excluded (Fig. 1). Additionally, two publications were identified through reference checking [18, 19]. One additional record was identified through reviewing the relevant evidence appraisals by NICE for the indication of first-line aRCC [20]. In total, 105 publications referring to 19 studies were identified. For the CABOSUN trial, the clinical study report (CSR) was provided by Ipsen Pharma, which comprised the final data for cabozantinib [13]. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the 19 identified trials.

3.2 Study Exclusions

Of the 19 identified studies, 17 were critically appraised; two studies could not be assessed, because only abstracts or posters were available (see Table 1). The assessment criteria that most of the studies fulfilled were the following: appropriate randomization (12 studies), balanced patient baseline characteristics between study arms (15 studies), no evidence of selective reporting (14 studies) and appropriate intent-to-treat (ITT) population analysis (16 studies). Nine studies had an open-label design, however, in 4 of these data were assessed by an independent imaging-review committee reducing the potential source of bias. Additionally, most of the studies (14) failed to report the method of treatment allocation concealment.

The publications were then assessed for data availability, and six studies were excluded. The CESAR [22], PISCES [24], PERCY Quattro [38]; Hinotsu 2013 [26], Study of Groupe Français d’Immunothérapie [39] and Boccardo 1998 [19] studies did not report OS/PFS HRs. Overall, 13 studies were retained for the NMA, providing data for pazopanib, bevacizumab, IFN, sunitinib, sorafenib, temsirolimus, cabozantinib, and tivozanib, while IL-2 was dropped due to lack of available data.

3.3 Characteristics of Study Populations

Across all trials, patients had similar median age (~ 60 years), and most of the patients included in the studies were male. In studies with available ethnicity data, most of the patients were Caucasian. The baseline risk characteristics of patients in the 13 included studies are summarized in Table 2. For studies with ECOG (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group) performance data available, most of the patients were in status 0 or 1. Only the CABOSUN and TORAVA (sunitinib versus bevacizumab plus temsirolimus versus bevacizumab plus IFN) studies included more than 10% of the population in ECOG status 2, while other studies included less than 5% of the population in this performance category. The CABOSUN study used the IMDC risk category instead of MSKCC. The NCT00117637, SWITCH, TARGET, and CROSS-J-RCC studies had only 0–1% of poor prognosis patients, which was rather low compared to other studies. In contrast, study NCT00065468 had rather high proportions of poor-prognosis patients (69% and 76% in the temsirolimus and IFN arms respectively). Overall, patients included in the NCT00065468 and CABOSUN studies had the least favorable prognoses, while those in the NCT00117637, SWITCH, TARGET, and CROSS-J-RCC studies had the best prognosis profiles. These differences in risk profiles warranted separate analyses in intermediate or poor risk sub-groups. In other respects, the patient characteristics were similar between the interventions.

The NMA was based on available HR data for OS and PFS as summarized in Table 3. Two studies had a cross-over design [23, 25]. Three studies enrolled pre-treated and treatment-naïve patients [27, 30, 31] but provided OS HR (n = 5) and PFS HR (n = 4) for the subgroup patients with no prior treatments; these HRs were used for the NMA. Two of the included studies were phase II studies (CABOSUN, NCT00117637), while the rest were phase III studies.

3.4 Network Meta-Analysis of OS and PFS

PFS outcomes were significantly increased for cabozantinib compared to all treatments in intermediate and poor-risk subgroups (see Figs. 2, and 3). In intermediate-risk patients, hazard ratios [HRs] were 0.52 (95% CI: 0.33, 0.82), 0.46 (95% CI: 0.26, 0.8), 0.2 (95% CI: 0.12, 0.36), and 0.37 (95% CI: 0.2, 0.68) when cabozantinib was compared with sunitinib, sorafenib, IFN, or bevacizumab plus IFN, respectively. In poor-risk patients, the NMA also demonstrated significantly longer PFS for cabozantinib; HRs were 0.31 (95% CI: 0.11, 0.9), 0.22 (95% CI: 0.06, 0.87), 0.16 (95% CI: 0.04, 0.64), and 0.20 (95% CI: 0.05, 0.88) when cabozantinib was compared with sunitinib, temsirolimus, IFN, or bevacizumab plus IFN, respectively.

The overall study populations in studies other than CABOSUN and ARCC/NCT00065468 included favorable-risk patients. When the HRs for the overall study populations were compared, PFS outcomes were significantly improved for cabozantinib compared to all treatments (Fig. 4). PFS HRs most strongly favored cabozantinib over the following comparators: IFN (HR = 0.24; 95% CI: 0.14, 0.38); temsirolimus (HR = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.19, 0.54); bevacizumab + IFN (HR = 0.35; 95% CI: 0.21, 0.57); and sorafenib (HR = 0.36; 95% CI: 0.23, 0.58). The HR for PFS also significantly favored cabozantinib over both pazopanib and sunitinib (HR = 0.48; 95% CI: 0.3, 0.75; and HR = 0.48; 95% CI: 0.31, 0.74, respectively). The HRs for OS consistently favored cabozantinib over comparators in subgroup and overall study population analyses, although these findings were not statistically significant (Figs. 5, 6, and 7). Results for placebo were calculated, because placebo provided a link in the network between sorafenib and pazopanib. However, placebo results are not a focus in this NMA, because BSC is not currently recommended as a treatment strategy for first-line treatment of aRCC [11].

4 Discussion

We herein report results from a systematic review and NMA conducted to indirectly compare cabozantinib with standard-of-care treatments used in the first-line treatment of aRCC patients. Because the risk profiles of patients varied across the trials, the NMA was conducted separately in intermediate- and poor-risk subgroups. We found that cabozantinib improves PFS significantly in intermediate- and poor-risk patients versus all comparators. While the OS results are not statistically significant, they nominally favor cabozantinib in both intermediate- and poor-risk populations. Most of the studies included in the network were phase III, but two of the studies were phase II; CABOSUN (cabozantinib versus sunitinib) and NCT00117637 (sorafenib versus IFN). Sorafenib and IFN comparisons are additionally informed by phase III studies. However, CABOSUN has a similar design to other contemporary trials in aRCC; it is a randomized, multicentre, open-label, active-controlled trial comparing efficacy and safety of cabozantinib versus sunitinib. In the overall study populations, including mostly studies that include favorable-risk patients, the results for cabozantinib are consistent with the results in more homogenous analyses of intermediate-, and poor-risk patients. While the subgroup analyses thus provide opportunities of comparisons in less heterogeneous study populations, the overall analyses allow more studies to be included in the network. In summary, the conclusions remain the same whether intermediate, poor, or overall populations are compared: PFS results are significantly better for cabozantinib, and OS results favor it but are not statistically significant. CABOSUN study prognostic risk was based on the IMDC model, whereas in other studies the prognostic risk was determined by using the MSKCC criteria. However, compared with other models [7], the IMDC model has a wider use and improved prognostic value, as acknowledged in the most recent ESMO guidelines [11]. It is valid both for previously untreated and treated patients and for non-clear cell RCC [47]. The various risk models are based on a similar set of prognostic criteria, and for the purposes of this analysis can be considered to be interchangeable.

Other, previous NMAs have compared first-line treatments for patients with aRCC. Leung et al. (2014) have conducted an NMA of data available prior to August 2013 using similar methodology to that of the current study (i.e., comparing the logarithm of the HRs [15]) [48]. Their results suggest that sunitinib and axitinib improve PFS over sorafenib, pazopanib and temsirolimus, although not all comparisons are statistically significant. Unlike the current study, the Leung et al. analysis includes patients with an ECOG performance status of 0 or 1, and some patients after nephrectomy or prior cytokine therapy. While our analysis does not include axitinib, their finding that sunitinib improves PFS compared to sorafenib, pazopanib, and temsirolimus is consistent with our analysis. More recent NMA studies have evaluated the available data for first-line antiangiogenic therapies in aRCC. An analysis conducted by Rousseau et al. (2016) evaluated the benefit of first-line treatments in aRCC using a direct weighted-average meta-analysis and an NMA using Bayesian hierarchical models with random effects [49]. Results of the direct meta-analysis demonstrate significant improvement in PFS for patients treated with sunitinib, pazopanib, axitinib, and bevacizumab plus IFN compared to placebo or IFN. Their NMA results show no significant differences among antiangiogenic drugs for 6-month PFS or 1-year OS. Chang et al. (2016) conducted an NMA using Bayesian hierarchical random effects models to compare efficacy and safety of 12 different treatment arms among 7597 patients with aRCC [50]. In contrast to our study, this study does not include cabozantinib and considers different comparators. Chang et al. reported sunitinib to be the best treatment modality in terms of PFS (rank probability value = 2.36) and safety (rank probability value = 7.43). The Chang et al. study did not select patients based on prognostic risk category, but the current study suggests that cabozantinib may be more efficacious than sunitinib in the first-line treatment of both intermediate- and poor-risk patient groups. Real-world studies of first-line treatment of aRCC have also been published [51, 52]. In our analysis, OS results for all groups (overall, intermediate and poor risk) were consistent with the findings in study by Lalani et al. (2017) [51]; i.e., sunitinib was more effective than pazopanib in our analysis. Basappa et al. (2017) [52] found that sunitinib given according to product monograph showed no difference in OS when compared to pazopanib given according to product monograph. An alternative regimen (individualized sunitinib dosing) was the most effective of the three treatment approaches compared. Lalani et al. and Basappa et al. also assessed time to treatment failure (TTF), whereas we analyzed PFS. Nevertheless, neither of the real-world studies showed a difference in TTF, consistent with our analysis where no difference in PFS was observed between sunitinib and pazopanib.

Several limitations of our study should be noted. As with all systematic reviews, there is potential for bias in the study selection. To minimize this risk, the literature review was conducted according to the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions [53]. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were pre-defined, and two independent reviewers conducted the work. Another weakness is that data for treatment-naïve patients were not available from all studies. Therefore, findings from the TARGET study were excluded from the OS network. To identify treatment-naïve OS results for the TIVO-1 study (Motzer 2013), additional manual searches of HTA agency websites were required [42]. Not all studies reported intermediate- and poor-risk group HRs. Four comparisons were possible in the intermediate-risk group (OS, PFS), and five and four comparisons were possible in the poor-risk group with OS and PFS endpoints respectively.

A limitation of the overall-population analysis is the difference between the studies regarding the proportions of patients with favorable-, intermediate-, and poor-risk factors. The CABOSUN study, by design, only included patients with intermediate and poor risk, whereas most other studies included patient populations with favorable-risk profiles. For this reason, in addition to the overall population analysis, we have performed comparisons in intermediate-, and poor-risk subgroups. The results of all analyses were consistent. The current study also has several strengths. The study quality of selected studies was systematically appraised using the NICE checklist, and studies were mostly considered to be of good quality, while a frequent source of potential bias was open-label design, which was reduced by involving an independent imaging-review committee in some of the studies. Our study also employed well-established HR NMA methodology, an approach that balances analysis complexity with ease of understanding and interpretation.

5 Conclusion

The current study suggests that cabozantinib is a promising first-line treatment for aRCC compared to available standard-of-care options. The results of this NMA may have clinical implications for the optimal approach to treat patients with aRCC, especially in light of the CABOSUN study, which demonstrated a clinical benefit versus sunitinib in patients with intermediate- or poor-risk aRCC. As the treatment landscape for aRCC evolves, future head-to-head clinical trials are also needed to ensure that robust clinical data are available for patients with different risk profiles across all treatment settings.

References

Ljungberg B, Bensalah K, Canfield S, Dabestani S, Hofmann F, Hora M, et al. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma: 2014 update. Eur Urol. 2015;67(5):913–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.01.005.

Chow WH, Devesa SS. Contemporary epidemiology of renal cell cancer. Cancer J. 2008;14(5):288–301. https://doi.org/10.1097/PPO.0b013e3181867628.

Znaor A, Lortet-Tieulent J, Laversanne M, Jemal A, Bray F. International variations and trends in renal cell carcinoma incidence and mortality. Eur Urol. 2015;67(3):519–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.002.

Gupta K, Miller JD, Li JZ, Russell MW, Charbonneau C. Epidemiologic and socioeconomic burden of metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): a literature review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2008;34(3):193–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2007.12.001.

Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Warren MA, Golshayan AR, Sahi C, et al. Prognostic factors for overall survival in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with vascular endothelial growth factor-targeted agents: results from a large, multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(34):5794–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.21.4809.

Motzer RJ, Bacik J, Schwartz LH, Reuter V, Russo P, Marion S, et al. Prognostic factors for survival in previously treated patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(3):454–63. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2004.06.132.

Heng DY, Xie W, Regan MM, Harshman LC, Bjarnason GA, Vaishampayan UN, et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(2):141–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70559-4.

Ko JJ, Choueiri TK, Rini BI, Lee JL, Kroeger N, Srinivas S, et al. First-, second-, third-line therapy for mRCC: benchmarks for trial design from the IMDC. Br J Cancer. 2014;110(8):1917–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/bjc.2014.25.

Rodriguez-Vida A, Hutson TE, Bellmunt J, Strijbos MH. New treatment options for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. ESMO Open. 2017;2(2):e000185. https://doi.org/10.1136/esmoopen-2017-000185.

Ruiz-Morales JM, Swierkowski M, Wells JC, Fraccon AP, Pasini F, Donskov F, et al. First-line sunitinib versus pazopanib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results from the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium. Eur J Cancer. 2016;65:102–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.06.016.

Escudier B, Porta C, Schmidinger M, Rioux-Leclercq N, Bex A, Khoo V, et al. Renal cell carcinoma: ESMO clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(Suppl 5):v58–68.

Yakes FM, Chen J, Tan J, Yamaguchi K, Shi Y, Yu P, et al. Cabozantinib (XL184), a novel MET and VEGFR2 inhibitor, simultaneously suppresses metastasis, angiogenesis, and tumor growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2011;10(12):2298–308. https://doi.org/10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0264.

Exelixis. Clinical study report. A031203. Randomized phase II study comparing cabozantinib (NSC #761968 and IND #116059) with commercially supplied sunitinib in subjects with previously untreated locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma. 2017 (31/07/2017).

Rücker G, Schwarzer G, Krahn U, König J. Netmeta: Network meta-analysis using frequentist methods. R package. Version 0.9–0. 2016.

Caldwell DM, Ades AE, Higgins JP. Simultaneous comparison of multiple treatments: combining direct and indirect evidence. BMJ. 2005;331(7521):897–900. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7521.897.

Rucker G. Network meta-analysis, electrical networks and graph theory. Res Synth Methods. 2012;3(4):312–24. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1058.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Single technology appraisal (STA). Pazopanib (Votrient®) for the first-line treatment of patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (RCC). Technology appraisal guidance [TA215]. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2010.

Sternberg CN, Eisen T, Tomczak P, Strahs AL, Esteves B, Berkenblit A. Tivozanib in patients treatment-naive for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a subset analysis of the phase III TIVO-1 study. J Clin Oncol. 2013;13(Suppl):A4513.

Boccardo F, Rubagotti A, Canobbio L, Galligioni E, Sorio R, Lucenti A, et al. Interleukin-2, interferon-alpha and interleukin-2 plus interferon-alpha in renal cell carcinoma. A randomized phase II trial. Tumori. 1998;84(5):534–9.

Tomita Y, Naito S, Sassa N, editors. Sunitinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy followed by sorefenib and sunitinib for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) with clear cell histology: a multicenter randomized trial, CROSS-J-RCC. Poster presented at ASCO GU; 2017 Feb 16–18; Orlando, FL.

Choueiri TK, Halabi S, Morris MJ, George D. Reply to B. Rini et al and S. Buti et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(16):1859–60. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2017.72.2629.

Bergmann L, Grunwald V, Maute L, Grimm MO, Weikert S, Schleicher J, et al. A prospective randomized phase-II trial with temsirolimus vs. sunitinib in non-clear renal cell carcinoma. A study of the CESAR Central European Society for Anticancer Drug Research-EWIV and Interdisciplinary Renal Cell Carcinoma Group of the German cancer society (IAGN). Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:S517.

Eichelberg C, Vervenne WL, De SM, von WL F, Goebell PJ, Lerchenmuller C, et al. SWITCH: a randomised, sequential, open-label study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of sorafenib-sunitinib versus sunitinib-sorafenib in the treatment of metastatic renal cell cancer. Eur Urol. 2015;68(5):837–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eururo.2015.04.017.

Escudier B, Porta C, Bono P, Powles T, Eisen T, Sternberg CN, et al. Randomized, controlled, double-blind, cross-over trial assessing treatment preference for pazopanib versus sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: PISCES study. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(14):1412–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/jco.2013.50.8267.

Tomita Y, Naito S, Sassa N, Takahashi A, Kondo T, Koie T, et al. Sunitinib versus sorafenib as first-line therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma with favorable or intermediate MSKCC risk factors: a multicenter randomized trial, CROSS-J-RCC. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(4 Suppl1):502.

Hinotsu S, Kawai K, Ozono S, Tsushima T, Tokuda N, Nomata K, et al. Randomized controlled study of natural interferon alpha as adjuvant treatment for stage II or III renal cell carcinoma. Int J Clin Oncol. 2013;18(1):68–74. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10147-011-0345-9.

Motzer RJ, Nosov D, Eisen T, Bondarenko I, Lesovoy V, Lipatov O, et al. Tivozanib versus sorafenib as initial targeted therapy for patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results from a phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(30):3791–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2012.47.4940.

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, Reeves J, Hawkins R, Guo J, et al. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(8):722–31. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1303989.

Negrier S, Gravis G, Perol D, Chevreau C, Delva R, Bay JO, et al. Temsirolimus and bevacizumab, or sunitinib, or interferon alfa and bevacizumab for patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma (TORAVA): a randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(7):673–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045%2811%2970124-3.

Negrier S, Jager E, Porta C, McDermott D, Moore M, Bellmunt J, et al. Efficacy and safety of sorafenib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma with and without prior cytokine therapy, a subanalysis of TARGET. Med Oncol. 2010;27(3):899–906. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12032-009-9303-z.

Sternberg CN, Davis ID, Mardiak J, Szczylik C, Lee E, Wagstaff J, et al. Pazopanib in locally advanced or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: results of a randomized phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(6):1061–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9764.

Escudier B, Szczylik C, Hutson TE, Demkow T, Staehler M, Rolland F, et al. Randomized phase II trial of first-line treatment with sorafenib versus interferon alfa-2a in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1280–9. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.19.3342.

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Oudard S, et al. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(22):3584–90. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1293.

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(2):115–24. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa065044.

Rini BI, Halabi S, Rosenberg JE, Stadler WM, Vaena DA, Ou SS, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa compared with interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: CALGB 90206. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(33):5422–8. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9847.

Escudier B, Pluzanska A, Koralewski P, Ravaud A, Bracarda S, Szczylik C, et al. Bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a for treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a randomised, double-blind phase III trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9605):2103–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61904-7.

Hudes G, Carducci M, Tomczak P, Dutcher J, Figlin R, Kapoor A, et al. Temsirolimus, interferon alfa, or both for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2271–81. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa066838.

Negrier S, Perol D, Ravaud A, Chevreau C, Bay JO, Delva R, et al. Medroxyprogesterone, interferon alfa-2a, interleukin 2, or combination of both cytokines in patients with metastatic renal carcinoma of intermediate prognosis: results of a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2007;110(11):2468–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.23056.

Negrier S, Escudier B, Lasset C, Douillard JY, Savary J, Chevreau C, et al. Recombinant human interleukin-2, recombinant human interferon alfa-2a, or both in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. Groupe Français d'Immunothérapie. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(18):1272–8. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199804303381805.

Exelixis. Clinical study report. A031203. Table 14.2.6.1 Kaplan–Meier analysis of overall survival by subgroup2017.

Sternberg CN, Hawkins RE, Wagstaff J, Salman P, Mardiak J, Barrios CH, et al. A randomised, double-blind phase III study of pazopanib in patients with advanced and/or metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final overall survival results and safety update. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49(6):1287–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.010.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Single technology appraisal. Tivozanib for treating renal cell carcinoma [ID591]. Committee papers, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2017.

Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, McCann L, Deen K, Choueiri TK. Overall survival in renal-cell carcinoma with pazopanib versus sunitinib. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(18):1769–70. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMc1400731.

Rini BI, Halabi S, Rosenberg JE, Stadler WM, Vaena DA, Archer L, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa versus interferon alfa monotherapy in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma: final results of CALGB 90206. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(13):2137–43. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.5561.

Escudier B, Bellmunt J, Negrier S, Bajetta E, Melichar B, Bracarda S, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab plus interferon alfa-2a in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (AVOREN): final analysis of overall survival. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(13):2144–50. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2009.26.7849.

Haute Autorité de Santé. Transparency Committee. Opinion. TORISEL 25 mg/ml concentrate and diluent for solution for infusion 1 vial of concentrate and 1 vial of diluent (CIP: 571 783–7). Haute Autorité de Santé 2008.

Ko JJ, Xie W, Kroeger N, Lee JL, Rini BI, Knox JJ, et al. The international metastatic renal cell carcinoma database consortium model as a prognostic tool in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma previously treated with first-line targeted therapy: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(3):293–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(14)71222-7.

Leung HW, Chan AL, Lin SJ. Indirect comparisons of efficacy and safety between seven newer targeted agents for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a network meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2(5):858–64. https://doi.org/10.3892/mco.2014.323.

Rousseau B, Kempf E, Desamericq G, Boissier E, Chaubet-Houdu M, Joly C, et al. First-line antiangiogenics for metastatic renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2016;107:44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.critrevonc.2016.08.012.

Chang L, An Y, Yang S, Zhang X. Meta-analysis of therapeutic effects and the risks of hypertension and hyperglycemia in patients with renal cell carcinoma who were receiving antiangiogenic drugs. J Cancer Res Ther. 2016;12(Supplement):96–103. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-1482.191614.

Lalani AA, Li H, Heng DYC, Wood L, Kalirai A, Bjarnason GA, et al. First-line sunitinib or pazopanib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: the Canadian experience. Can Urol Assoc J. 2017;11(3–4):112–7. https://doi.org/10.5489/cuaj.4398.

Basappa NS, Lalani A-KA, Li H, Kalirai A, Wood L, Kollmannsberger CK et al. Individualized treatment with sunitinib versus standard dosing with sunitinib or pazopanib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC): results from the Canadian Kidney Cancer information system (CKCis). J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(6 Suppl):468.

Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of Interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011.

Acknowledgements

Editorial assistance in the preparation of this article was provided by Karina Berenson and Dr. Silvia Paddock. Support for the study and writing assistance was funded by Ipsen Pharma SAS.

Funding

Analytica Laser received funding for this study from Ipsen Pharma SAS.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

Florence Marteau and Anne-Lise Vataire are employees of Ipsen Pharma SAS. Elvira Schmidt, Johanna Lister, Monika Neumann, Witold Wiecek, Shuai Fu, Jelena Sostar, Shengnan Huang are employees of Analytica Laser, who were paid contractors to Ipsen in the development of this manuscript. This research was performed under a research contract between Analytica Laser and Ipsen.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(PDF 574 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Schmidt, E., Lister, J., Neumann, M. et al. Cabozantinib Versus Standard-of-Care Comparators in the Treatment of Advanced/Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma in Treatment-naïve Patients: a Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis. Targ Oncol 13, 205–216 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-018-0559-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11523-018-0559-0