Abstract

Family-to-work conflict has received less attention in the literature compared to work-to-family conflict. This gap in knowledge is more pronounced during the COVID-19 pandemic, despite the documented increase in family responsibilities in detriment of work performance, particularly for women. Job satisfaction has been identified as a mediator between the family and work domains for the individual, but these family-to-work dynamics remain unexplored at a dyadic level during the pandemic. Therefore, this study tested the relationship between family-to-work conflict and job and family satisfaction, and the mediating role of job satisfaction between family-to-work conflict and family satisfaction, in dual-earner parents. A non-probability sample of 430 dual-earner parents with adolescent children were recruited in Rancagua, Chile. Mothers and fathers answered an online questionnaire with a measure of family-to-work conflict, the Job Satisfaction Scale and Satisfaction with Family Life Scale. Data was analysed using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model with structural equation modelling. Results showed that, for individuals, a higher family-to-work conflict is linked to lower satisfaction with both their job and family life, and these two types of satisfaction are positively associated with one another. Both parents experience a double negative effect on their family life satisfaction, due to their own, and to their partner’s family-to-work conflict; however, for fathers, this effect from their partner occurs via their own job satisfaction. Limitations and implications of this study are discussed, indicating the need of family-oriented workplace policies with a gender perspective to increase satisfaction in the family domain for workers and their families.

Similar content being viewed by others

Declarations.

Consent.

All participants read and signed informed consent forms regarding participating in the study and publication of their anonymized data.

Job satisfaction as a mediator between family-to-work conflict and satisfaction with family life: A dyadic analysis in dual-earner parents.

Introduction

The work and family domains are permeable, and individuals cross the borders between both spheres daily (Campbell-Clark, 2000; Kuschel, 2017). The tensions that workers experience between work and family demands can spill over not only to other life domains of their own, but they can also have a crossover effect, that is, they can influence outcomes for the workers’ family members (Kuschel, 2017; Westman, 2001). The spillover-crossover model (SCM, Bakker & Demerouti 2013) helps analyze these effects by examining experiences that are transmitted inter-individually from one domain to another (spillover), and between domains and between individuals in a close relationship (crossover). The SCM is helpful to analyze tensions in the work-family interface termed work-to-family conflict when strain from the workplace negatively affects family life. and family-to-work conflict, when the strain originated in the family domain affects the workplace (Clercq et al., 2019; Soomro et al., 2018; Venkatesh et al., 2019). Amstad et al. (2011) posit that, although both concepts are correlated, there is sufficient evidence that calls for analyzing each direction of this conflict separately. The literature has focused more frequently on work-to-family conflict (Al-Alawi et al., 2021; Kuschel, 2017), while the dynamics surrounding family-to-work conflict have received less attention on their own.

The need to examine the distinct dynamics of work-family and family-work conflict is more pronounced in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Since the pandemic was declared in March 2020 (World Health Organization, 2020a), lockdown measures designed to curb risk of contagion (i.e., working from home, remote learning for students) have increased both job and family demands (Ghislieri et al., 2021). While levels of work-to-family conflict have surged during the pandemic (Andrade & Petiz Lousã, 2021; Ghislieri et al., 2021) indicate that this conflict has been largely unaffected by lockdown measures, whereas family-to-work conflict has increased, with family responsibilities multiplying for those working from home (Andrade & Petiz Lousã, 2021). Studies on family-to-work conflict during the pandemic have negatively associated this conflict with post-traumatic growth (i.e., psychological changes after overcoming a crisis), directly and via a negative association with psychological capital and perceived social support (Lv et al., 2021); and with COVID-19 phobia (Karakose et al., 2021). During this period, women have reported more family-to-work conflict than men (Frank et al., 2021), which is consistent with the evidence that their home- and family-related responsibilities have increased during the pandemic more than for men (Jiménez-Figueroa et al., 2020; Orellana & Orellana, 2020; Schnettler et al., 2022a). Nevertheless, the work-from home conditions can have negative consequences in the workplace for men and women (Frank et al., 2021), as workers juggle job responsibilities while tending to their families (Karose et al., 2021).

In this study, following the conservation of resources theory (COR, Hobfoll 1989), we propose that family-to-work conflict entails the loss of personal resources (e.g., energy, time, moods) that has an impact not only the domain that receives this effect (work), but also on the domain that originates the conflict (family). The transmission or loss of resources between domains can be seen from the perspective of border theory (Clark, 2000), which examines the degree of segmentation or integration between work and family. A greater integration results in greater family-to-work conflict (Yung, 2015), and thus in a greater loss of personal resources to be invested in diverse outcomes. Studies during the COVID-19 pandemic have shown that the boundaries between work and domestic responsibilities have blurred even more (Easterbrook-Smith, 2020). We focus here on the outcomes of satisfaction with family life and job satisfaction, respectively, both linked to workers’ subjective well-being. Moreover, we propose, in keeping with previous studies, that family demands and their effects can crossover between different-gender partners (Brough et al., 2018; Dikkers et al., 2007).

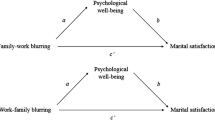

These crossover dynamics proposed can be examined using the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM, Kenny et al., 2006). The unit of analysis in the APIM is the dyadic interaction, and each member of the dyad is both an actor and a partner. This is a useful approach to examine how the work-family interface influence both members in dual-earner couples as it allows to observe interrelations between domains and between individuals. Actor effects are those relationships between two variables for the same individual (intra-individual effects or spillover), and partner effects are those relationships between an actor’s variable and a partner’s outcome (inter-individual effects or crossover). According to Hayes and Preacher (2014), causality cannot be demonstrated by statistical models, but they can help establish a causal argument; in this study, causality is proposed by establishing actor and partner effects. Figure 1 shows the proposed model. On this basis, this study tested the relationship between family-to-work conflict and job and family satisfaction, and the mediating role of job satisfaction between family-to-work conflict and family satisfaction, in dual-earner parents with adolescent children.

Conceptual model of the proposed actor and partner effects between Family-to-Work Conflict (FtoWC), Job Satisfaction (OJSS), and Satisfaction with Family Life (SWFaL) in dual-earner parents with adolescent children

Em and Ef: residual errors on SWFaL for the mothers and fathers, respectively

The indirect effects of Job Satisfaction (H3) were not shown in the conceptual path diagram to avoid cluttering the figure

Relationships between family-to-work conflict, job satisfaction and family life satisfaction

Conflict

between the work and family domains can be understood following the COR theory (Hobfoll, 1989). According to the COR, individuals are motivated to obtain, retain and protect things that they value, or resources, which help them deal with stressors. For ten Brummelhuis & Bakker (2012), personal resources can be physical (e.g., energy), intellectual (e.g., skills), psychological (e.g., focus, attention), affective (e.g., positive moods, empathy), and capital (e.g., time). These and other resources (see Hobfoll et al., 2018) not only protect individuals from stressors, but also allow them to accumulate more resources that can be associated with well-being outcomes (Matei & Vîrgă, 2022). In dual-earner couples, Matei & Vîrgă (2022) have shown that individuals with personal resources (in their study, communication quality) are more willing to invest these resources in other life roles or domains. On the other hand, high contextual demands from one domain can entail a loss spiral (Bakker & Demerouti, 2016; ten Brummelhuis & Bakker, 2012), in which personal resources are weakened or depleted as individuals invest them to respond to those high demands.

Studies on family-to-work conflict are often supported by the spillover model, which examines how resource strain and generation in one domain influence the other in the same individual (Kuschel, 2017). Family issues, such as difficult relationships with the partner or children (e.g., children’s misbehavior, Venkatesh et al., 2019), can spill over into the work life. Family demands can lead employees to invest more resources in the family domain while they might decrease workers’ ability to perform their job (Clercq et al., 2019), for instance, leading them to lose concentration from work, and to realigning schedules and priorities to meet their job requirements and the family demands (Soomro et al., 2018). Clark’s (2000) border theory is concerned with these blurred boundaries between work and family. The demands from either the job or the family role can make transitioning between roles difficult. For instance, working from home can contribute to the overall work-family conflict as it requires to multitask on work and family responsibilities (Young, 2015). In other words, the workplace and family life are interconnected (Matei et al., 2021), and their boundaries overlap (Young, 2015).

These cross-domains relationships led Frone et al., (1992) to assume that conflict that originates in one domain causes problems in the other domains. This assumption allows to explain the link between family-to-work conflict and work-related outcomes such as job satisfaction (Venkatesh et al., 2019). Job satisfaction is the extent to which workers like their job (Agho et al., 1992), and a key factor in employee performance (Soomro et al., 2018). According to Venkatesh et al., (2019) when individuals cannot meet the demands at work due to family interference with their job, they have less satisfactory performance and less engagement with work. Evidence on the relationship between family-work conflict and job satisfaction is mixed, however. Some studies (Al-Alawi et al., 2021; De Simone et al., 2014; Frye & Breaugh, 2004) report no significant correlation between family-work interface and job satisfaction. Soomro et al., (2018) explain that this null finding is more prominent in developing countries and suggest that this is due to job satisfaction being interpreted differently in developing and developed countries. On the contrary, other studies (Clercq et al., 2019; Clercq, 2020) have suggested a significant relationship between these two constructs, given that resource depletion derived from family-to-work conflict was found to also reduce helping behavior among organizational members. Overall, following the COR and border theories, we expect that strain caused in the family domain will negatively affect the individual’s work role, and this impact will be reflected in their job satisfaction.

From the cross-domain stance, job satisfaction has been found to positively influence the family domain (e.g., family development, Jiménez-Figueroa et al., 2020). Given that family-to-work conflict can have noticeable effects on domain-specific satisfaction (De Simone et al., 2014), the impact of both family-to-work conflict and job satisfaction in the family domain may be better assessed by examining satisfaction with family life, the person’s subjective, conscious assessment of their family life (Zabriskie & Ward, 2013). Several studies support a positive relationship between job and family satisfaction (Emanuel et al., 2018; Morr & Droser, 2020; Musadieq 2019; Schnettler et al., 2020). Both work and family satisfaction are frequent outcomes of work-family and family-work conflict, yet correlation patterns for between conflict and satisfaction may depend on the domain that is causing the conflict (Amstad et al., 2011).

In this regard, a competing explanation to the cross-domain relationships is the matching hypothesis (Amstad et al., 2011). According to this hypothesis, the primary effects of a conflict are found in the domain in which the conflict originates. Given that the domain that is causing the problem is a source of negative affective responses, strain reactions are expected to be dominant in this domain (Amstad et al., 2011). For instance, as posed by Amstad et al. (2011), if the worker finds that their workload interferes with the time dedicated to their family, the worker might be angry or resentful against their workplace, and such discontent might be reflected in their job satisfaction. On the opposite direction, if family responsibilities are seen as the cause for having too little time for accomplish an important deadline in the workplace, the worker might be angry or resentful against their family, and thus experience lower family satisfaction. According to the matching hypothesis, family-originated resource strain should thus have a stronger effect on the family domain than on the work domain. However, the link between family-to-work conflict and family satisfaction is unclear, as studies have mainly focused on this relationship from a work-to-family standpoint (Kuscher, 2017).

Amstad et al. (2011) provide evidence supporting both the cross-domains relationships and the matching hypothesis for both directions of work-family conflict. In the meta-analysis conducted by these authors, work-to-family conflict was significantly related to both work-related and family-related outcomes, while family-to-work conflict was related also to both family-related and work-related outcomes. Regardless of the above, these authors found that work-to-family conflict was more strongly associated with work-related outcomes than with family-related outcomes, while family-to-work conflict was more strongly associated with family-related outcomes than with work-related outcomes. These authors concluded that the evidence provide more support to the matching hypothesis, although the cross-domain relationship cannot be ruled out.

Results from a more recent meta-analysis on the work-family interface (Matei et al., 2021) found strongest effect sizes between-partner correlations of the same type of outcome, i.e., the correlation for work-family conflict and family-related well-being was stronger than correlation for work-related well-being, providing evidence to support the cross-domains hypothesis. Matei et al., (2021) show that work-family conflict is negatively associated with family-related well-being in wives and husbands. Drummond et al., (2017) found that work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict negatively correlated with both job and family satisfaction, although when they tested the relationship between family-to-work conflict and family and job satisfaction one year later, the relationship between family-to-work conflict and family satisfaction was stronger than the relationship between family-to-work conflict and job satisfaction, also providing more support to the matching theory. In addition, Morr and Droser (2020) also provides provide support to the matching theory, as they found that a behavior- and strain-based family interference with work correlated negatively with family satisfaction. Therefore, we expect a negative relationship between family-to-work conflict and family satisfaction based on the matching hypothesis, and a negative relationship between family-to-work conflict and job satisfaction based on the cross-domain hypothesis. We thus propose the following hypotheses regarding actor effects for mothers and fathers in dual-earner couples (Fig. 1):

Hypothesis

a: the father’s family-work conflict is negatively related to his family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

b: the mother’s family-work conflict is negatively related to her family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

c: the father’s family-work conflict is negatively related to his job satisfaction.

Hypothesis

d: the mother’s family-work conflict is negatively related to her job satisfaction.

Hypothesis

e: the father’s job satisfaction is positively related to his family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

f: the mother’s job satisfaction is positively related to her family satisfaction.

The family-to-work conflict might also have crossover effects (Westman, 2001), that is, this conflict and its outcomes may also be experienced by others with whom the worker has a close relationship, including family members (Bakker & Demerouti, 2013). Evidence suggests that work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict are indeed involved in spillover and crossover processes in dual-earner couples (Li et al., 2021; Matei et al., 2021; Matei & Vîrgă, 2022) and in parent-child dyads (Orellana et al., 2021b; Schnettler et al., 2021c). In their meta-analysis, Matei et al., (2021) found that wife/husband’s work-to-family conflict was negatively related to his/her partner’s family-related well-being. In another meta-analysis focused on work-to-family and family-to-work crossovers, Li et al., (2021) found that one member of the couple’s work-family conflict was negatively related to the other member’s family satisfaction (medium size effect) and work attitudes such as job satisfaction and engagement (small size effect). Although these and other studies show that conflicting work and family roles affect both the individual (Emanuel et al., 2018) and their partner (Liang, 2015) regardless of gender, other findings indicate an asymmetrical transmission of resources or strain in different-gender couples, that is, an influence from one partner to the other, but not vice versa (Orellana et al., 2021a; Matei & Vîrgă, 2022).

This gender asymmetry may be due to the societal demand of making a gendered and clear-cut division of work and family, which affects women more strongly than men because women are perceived, and they perceive themselves, as the main carer of the family (Bilodeau et al., 2020). Consequently, women tend to experience more psychological strain when the conflict goes from the family to the workplace, compared to men who are more affected by work-to-family conflict (Bilodeau et al., 2020). Some studies, however, have reported no gender differences in the degree of neither work-to-family (Jiménez-Figueroa et al., 2020) nor family-to-work conflict (Entrich et al., 2007). These mixed reports in the literature could be due to sample characteristics, such as type of employment, access to benefits or weekly working hours (Jiménez-Figueroa et al., 2020), or to the ages of the workers’ children, given that individuals with older children may experience lower work-family conflict and family-work conflict than those with younger children (Entrich et al., 2007).

Studies on work-to-family conflict have linked this construct to both lower family life quality and lower job satisfaction (Wang & Peng, 2017), and similar results may be expected for family-to-work conflict, although it is not clear the extent to which this conflict affects men and women differentially. Frye & Breaugh (2004) found no crossover association between family-to-work conflict and job satisfaction. Dikkers et al., (2007) found that husbands’ job demands (i.e., workload) increased their wives’ home demands (i.e., housework), but the inverse relationship (i.e., wives’ workload and husbands’ housework) was not tested. Using a qualitative approach, Brough et al., (2018), established that one partner’s work events crossed over to the other partner’s work outcomes and dyadic outcomes (i.e., relationship satisfaction). Building on the above literature on crossover work-family dynamics, we propose the following hypothesis (Fig. 1):

Hypothesis

a: the father’s family-work conflict is negatively related to the mother’s family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

b: the mother’s family-work conflict is negatively related to the father’s family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

c: the father’s family-work conflict is negatively related to the mother’s job satisfaction.

Hypothesis

d: the mother’s family-work conflict is negatively related to the father’s job satisfaction.

Hypothesis

e: the father’s job satisfaction is positively related to the mother’s family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

f: the mother’s job satisfaction is positively related to the father’s family satisfaction.

In an exploratory manner (i.e., no hypothesis), we also suggest that different gender patterns may be found in crossovers between family-to-work conflict and job and family satisfaction. This suggestion accounts for the gender dynamics of the Latin American context, in which women have been traditionally tasked with domestic labor and childrearing, regardless of their employment status, whereas men have been expected to have a paid job outside the house (Jiménez-Figueroa et al., 2020). Stressors that stem from the family domain can lead to family-work conflict in both parents (e.g., children’s misbehavior, Venkatesh et al., 2019), but mothers may be more frequently tasked with dealing with these stressors.

Furthermore, despite an expected decrease in family-to-work conflict as children age (Entrich et al., 2007), raising adolescents also entails significant challenges for parents. The World Health Organization (2020b) establishes that adolescence begins at around age 10. According to Matias & Recharte (2021), the adolescence period is an interesting context in which to study work-family dynamics, given the adolescents’ needs for both independence and support from their parents, and the latter’s desire to keep a sense of control over their adolescents’ decisions. Developmental changes in adolescence entail challenges and vulnerabilities that disturb the entire family system, and which require that parents and adolescents constantly renegotiate their boundaries (Matias & Recharte, 2021; Wang et al., 2022). Parents’ must invest time and emotional resources to respond to their children’s needs, and job stressors can lead to an energy depletion that negatively impacts the parent-adolescent relationship (Hagelskamp & Hughes, 2016). The demands of parent-adolescent dynamics have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic, as parents struggle to balance their work while supporting their children’s autonomy and educational and mental health needs (von Soest et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022). In the COVID-19 context, adolescents are at a lower risk of contagion than older populations (Lacomba-Trejo et al., 2020), but are at a higher risk of lower well-being and higher distress due to the interruption of their developmental tasks (Orellana & Orellana, 2020). Adolescents thus require more support from their primary caregivers, who are most often their mothers (Lacomba-Trejo et al., 2020).

Overall, interferences from the home can create a role conflict that affects the workers’ job performance, while interferences generated on the job can also be transferred to the family domain (Ghislieri et al., 2021; Soomro et al., 2018). For this reason, satisfaction in both domains (i.e., work and family) can be negatively associated with family-to-work conflict (Al-Alawi et al., 2021), and positively associated with one another (Emanuel et al., 2018). During the pandemic, for instance, family responsibilities (e.g., fostering emotional adjustment in adolescent children, Lacomba-Trejo et al., 2020) may increase professional isolation (Andrade & Petiz Lousã, 2021) or interfere with job performance (Karakose et al., 2012). In turn, job satisfaction can affect family related variables, acting as a mediator between the work and family domains (Emanuel et al., 2018).

Lastly, building on the cross-domains and the matching hypotheses, we propose that job satisfaction has a mediating role between family-to-work conflict and family satisfaction. According to the cross-domain theory, family-to-work conflict should predominantly influence the work domain because conflict originated in one domain (i.e., family) cause problems in the other domain (i.e., work, Frone et al., 1992). Moreover, according to the matching hypothesis, the primary effects of a conflict are found in the domain in which the conflict originates (Amstad et al., 2011). As evidence supports both hypotheses at intra-individual and inter-individual levels (Amstad et al., 2011; Li et al., 2021; Matei et al., 2021; Morr & Droser, 2020; Drummond et al., 2017), we pose that family-to-work conflict indirectly reduces family satisfaction via a reduction of job satisfaction. In other words, if individuals cannot meet the demands at work due to family interference with their job they will experience job dissatisfaction, which in turn may generate a negative affective reaction against family, thus negatively influencing family satisfaction. This assumption is also consistent with the border theory inasmuch boundaries between family and work overlap. In addition, studies show that job satisfaction is a significant mediator between work-to-family conflict and depression in professional women in China (Wang & Peng, 2017), and between family-to-work conflict and employee performance in Saudi Arabian women in the public education sector (Al-Alawi et al., 2021). Research also shows that family-to-work conflict can partially mediate the effects that the family domain has on job satisfaction and other job outcomes (Ford et al., 2007; Venkatesh et al., 2019), suggesting that family-to-work conflict can be antecedent of job satisfaction. Moreover, job satisfaction has been found to be a mediator between job insecurity and family satisfaction, both for actor and partner, indistinctive of gender (Emanuel et al., 2018). Taken together, these findings establish job satisfaction as an intermediate variable, with family-to-work conflict as its antecedent and family satisfaction as its outcomes, both individually and in dyads. We thus propose this third and last hypothesis (Fig. 1):

Hypothesis

a: the father’s job satisfaction has a mediating role between his own family-work conflict and family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

b: the mother’s job satisfaction has a mediating role between her own family-work conflict and family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

c: the father’s job satisfaction has a mediating role between the mother’s family-work conflict and family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

d: the mother’s job satisfaction has a mediating role between the father’s family-work conflict and family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

e: the father’s job satisfaction has a mediating role between the mother’s family-work conflict and the father’s family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

f: the mother’s job satisfaction has a mediating role between her own family-work conflict and the father’s family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

g: the father’s job satisfaction has a mediating role between his own family-work conflict and the mother’s family satisfaction.

Hypothesis

h: the mother’s job satisfaction has a mediating role between the father’s family-work conflict and the mother’s family satisfaction.

Method

Sample and procedure

A non-probability sample of 430 dual-earner families was recruited in Rancagua, Chile. This study is part of a wider research on the relations between work, family, and food-related life in Chilean families [information omitted for anonymous review]. Sample size was determined considering 10 participants for each item of each scale used in this project. According to Soper (2022), the sample size used in this study allows to identify medium effect sizes (γ = 0.20) with power 1-Beta = 0.83. Inclusion criteria was that these families were composed of mother, father (married or cohabiting), and at least one adolescent child between 10 and 16 years old (Table 1). Families were recruited via schools in the city serving populations from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds. Parents received information from trained interviewers about the study’s objectives, questionnaire content, and the anonymous and confidential treatment of all data provided. Data collection was conducted between March and July 2020. The COVID-19 pandemic was declared in March 2020, and while some sanitary measures were implemented in Rancagua at the time, mandatory lockdown was enforced until June 2020 (Gobierno Regional Región de O’Higgins, 2020). To ensure the safety of both the participants and the research team, data collection was fully conducted online. Families who agreed to participate in the study received the links to two separate questionnaires (one for each parent) via e-mail during March and July 2020. The first page of each questionnaire displayed either an informed consent form, for mothers and fathers. Mothers and fathers provided consent to participate by ticking a box before filling out the questionnaire, and their responses were registered in the QuestionPro platform (QuestionPro Inc) separately. In retribution for their participation, families received a 15 USD gift card. The Ethics Committee of the [information omitted for anonymous review] approved this study.

The study procedure was pilot tested with 50 families that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. The recruitment method and data collection procedures stated above were followed. Results were deemed satisfactory with no changes required neither in the instrument nor in the data collection procedure.

Measures

Family-to-work conflict was measured with four items, adapted from Frone et al., (1992), and Netemeyer et al., (1996, see Kinnunen et al., 2006). These items enquire about negative spill over from family to work (example item: “Your home life prevents you from spending the desired amount of time on job- or career-related activities?”). Response options are presented on a five-point scale (1: never; 5: very often). Researchers have reported good internal consistency for this measure (De Simone et al., 2014). The Spanish version of this measure was used (Schnettler et al., 2018). In the present study, the standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.851 to 0.890 for mothers and from 0.878 to 0.933 for fathers, all statistically significant (p < .001). The AVE values were higher than 0.50 (AVE mothers = 0.77, fathers = 0.80). This measure also showed good internal reliability, with an Omega coefficient of 0.92 for mothers and 0.94 for fathers.

Job satisfaction was measured with the Overall Job Satisfaction Scale (OJSS), which comprises six items selected by Agho et al., (1992, example item: “I find real enjoyment in my job”) from an 18-item index developed by Bradfield and Rothe (1951). Respondents indicated their degree of agreement with each statement using a five-point Likert scale (1: completely disagree; 5: completely agree). OJSS scores were obtained via a sum of the scores from the six items, with higher scores representing a greater job satisfaction. The OJSS has shown good internal consistency in samples from different countries (Agho et al., 1992; Korff et al., 2017). The Spanish version of the OJSS scale was used, which has been validated and shown good internal consistency in studies with couples in Chile (Schnettler et al., 2020, 2022a). In the present study, the standardized factor loadings of the OJSS scale ranged from 0.582 to 0.909 for mothers and from 0.496 to 0.922 for fathers, all statistically significant (p < .001). The AVE values were higher than 0.50 (AVE mothers = 0.66, fathers = 0.63). The OJJS scale showed good internal reliability, with Omega coefficients of 0.92 for mothers and 0.90 for fathers.

Family life satisfaction was measured with the Satisfaction with Family Life Scale (SWFaL, Zabriskie & Ward, 2013). This five-item scale is an adaptation of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985), in which all items refer to “family life” instead of “life” in the original version. Response options are presented on a six-point Likert-type response format (1: completely disagree; 6: completely agree). The Spanish version of the SWFaL scale was used in this study (Schnettler et al., 2017), which has shown good psychometric properties and good levels of internal consistency in Chilean adult samples (Schnettler et al., 2017, 2020, 2021a, b). In the present study, the standardized factor loadings of the SWFaL ranged from 0.802 to 0.940 for mothers and from 0.080 to 0.946 for fathers, all statistically significant (p < .001). The AVE values were higher than 0.50 (mothers’ AVE = 0.73, fathers’ AVE = 0.77). In this study, a good level of reliability was obtained, with Omega coefficients of 0.93 for mothers and 0.95 for fathers.

Both parents also reported their age, their type of employment, the number of working hours per week and their monthly income. Mothers reported the number of family members and children in the household. The definition of SES in Chile considers two variables: total household income and household size. Total household income is the fundamental variable for socioeconomic segmentation, due to its predictive power on access to goods and services, and because the inverse relationship is much weaker: access to goods and services is not a good predictor of income. The size of the household exerts a restriction on purchasing power: When an additional member is added to the household without increasing income, basic expenses increase although in a sub-proportionate way since there are economies of scale. The combination of ranges of the household monthly income and the number of family members in a matrix determines the SES (Asociación de Investigadores de Mercado [AIM], 2016).

Data analysis

Descriptive analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) v.23. Prior to hypothesis testing, common method variance (CMV, Chang et al., 2010) was examined by conducting Harman’s single-factor test for mothers and fathers separately. All items from the measured constructs –Family-to-work conflict, the Satisfaction with Family Life scale, and the Overall Job Satisfaction Scale– were loaded into a factor analysis. This procedure shows whether one single factor emerges or whether more factors are detected and one of them leads to most of the covariance among these three measures. CMV is not a concern if no single factor emerges and accounts for majority of the covariance (Chang et al., 2010). This test was conducted in SPSS using principal component analysis (PCA) without rotation.

The Actor-Partner Interdependence Model (APIM) with distinguishable dyads was tested using structural equation modelling (SEM, Kenny et al., 2006) with Mplus 8.4. In this study, fathers and mothers are both an actor and a partner in the analysis. APIM associations between variables for the same parent are termed “actor effects”, and associations between variables from one parent to the other are “partner effects”. The actor and partner effects tested were family-to-work conflict (FtoWC), job satisfaction (OJSS) and satisfaction with family life (SWFaL).

Besides actor and partner effects, the APIM allows to control for other effects. In this regard, one parent’s effect on the other in terms of FtoWC was controlled for by specifying a correlation between this independent variable reported by each parent. Other sources of interdependence between partners were controlled for, as suggested by Kenny et al., (2006), by specifying correlations between the residual errors of the dependent variable (SWFaL) of the two parents. Other effects controlled for with possible direct effects on the dependent variables of both parents (OJSS and SWFaL) were parents’ age, type of employment and number of working hours, the family SES and the number of children. These variables were thus incorporated in the model.

The SEM was conducted using the weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) to estimate the structural model parameters. The polychoric correlation matrix was considered for the SEM analysis because items were of ordinal nature. The model fit of the data was determined using the following values: The Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and the comparative fit index (CFI), which show a good fit with values above 0.95; and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), which shows a good fit when values are below 0.06 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Differences between actor effects (intra-individual effects of family-to-work conflict on job and family life satisfaction, and job satisfaction on satisfaction with family life) and partner effects (individual’s effects of family-to-work conflict on their partner’s job and family life satisfaction, and the individual’s job satisfaction on their partner’s satisfaction with family life) were explored based on gender. Differences between both path coefficients were tested using a structural equation model.

Lastly, to test the mediating role of job satisfaction between the independent and dependent variables, a SEM through a bias-corrected (BC) bootstrap confidence interval using 1,000 samples (Lau & Cheung, 2012) was conducted. A mediating role is supported when BC confidence intervals do not include zero.

Results

Sample description

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample encompassing 430 dual-earner couples are shown on Table 1. On average, mothers were 39.5 years old and fathers 42.3 years. The difference between mothers’ and fathers’ age was significant (p < .001). Families were composed of an average of four family members and two children. Most families had a middle SES. Most of the parents in this sample –women and men– were employees versus independent workers. Compared to mothers, there was a greater proportion of fathers who worked full time (45 h per week in Chile, p < .001). Compared to mothers, there was a greater proportion of fathers who were employees (p < .001).

Assessing common method variance

Following the Harman’s single-factor test, the generated PCA output for the three measures used in this study revealed three distinct factors for each parent, accounting for 71.5% and 70.2% of the total variance for mothers and fathers, respectively. The first unrotated factor (i.e., family-to-work conflict) captured only 33.1% and 33.8% of the variance in data for mothers and fathers, respectively. Overall, no single factor emerged, and the first factor did not capture most of the variance in mothers and fathers, and hence CVM appears to be not an issue in this study (Chang et al., 2010).

Analysis of associations between variables

Table 2 shows the average scores and correlations for family-to-work conflict (FtoWC), job satisfaction (OJSS), and satisfaction with family life (SWFaL). Most of the correlations were significant and in the expected directions. For both mothers and fathers, at an intra-individual level, FtoWC correlated negatively with OJSS and SWFaL, while the latter two variables correlated positively with one another (all p < .05). These three measures also correlated between parents, except for the father’s FtoWC and the mother’s OJSS, which were not significantly associated. Mothers scored significantly higher than fathers in FtoWC (t = 3.646, p = < 0.001). Mothers and fathers did not differ in the average scores for OJSS (t = 0.938, p = .349). Fathers scored significantly higher than mothers in SWFaL (t = -2.691, p = .007).

APIM results: testing actor-partner hypotheses

The results from the estimation of the structural model are shown in Fig. 2. The model that assessed the APIM association between the mother’s and father’s family-to-work conflict (FtoWC), job satisfaction (OJSS), and satisfaction with family life (SWFaL) had a good fit with the data (CFI = 0.988; TLI = 0.986; RMSEA = 0.033). A significant correlation (covariance) was found between both parents’ FtoWC (r = .440, p < .001), and between the residual errors of mother’s and father’s SWFaL (r = .490, p < .001).

Actor-partner interdependence model of the effect Family-to-Work Conflict (FtoWC), Job Satisfaction (OJSS), and Satisfaction with Family Life (SWFaL) in dual-earner parents with adolescent children

Em and Ef: residual errors on SWFaL for mothers and fathers, respectively

* p < .05

** p < .01

The control for the effects of both parents’ age, type of employment and their number of working hours as well as the family SES and the number of children on the dependent variables of both parents (OJJS and SWFaL) were not shown in the path diagram

H1 stated that family-to-work conflict, job satisfaction, and family satisfaction are significantly associated for each parent. This hypothesis was divided in six statements (H1a to H1f) to observe the actor effects from FtoWC to SWFaL and OJSS, and from OJSS to SWFaL in mothers and fathers. The path coefficients (standardized) indicated that the father’s (γ = − 0.202, p = .001) and the mother’s (γ = − 0.146, p = .011) FtoWC was negatively associated with their own satisfaction with family life (H1a and H1b supported). Likewise, father’s (γ = − 0.186, < 0.001) and mother’s (γ = − 0.216, p < .001) FtoWC was negatively associated with their own job satisfaction (H1c and H1d supported). Moreover, father’s (γ = 0.238, < 0.001) and mother’s (γ = 0.152, p = .002) job satisfaction was positively associated with their own satisfaction with family life (H1e and H1f). These findings supported H1 for both parents (Fig. 2).

H2 sought partner effects, stating that one parent’s family-to-work conflict, job satisfaction, and family satisfaction are associated with the job satisfaction and family satisfaction of the other parent. This hypothesis was also divided in six statements (H2a to H2f) to observe the partner effects from FtoWC to SWFaL and OJSS, and from OJSS to SWFaL between mothers and fathers. The father’s FtoWC was negatively associated with the mother’s satisfaction with family life (γ = − 0.158, p = .009), thus supporting H2a. By contrast, H2b was not supported, the mother’s FtoWC was not statistically associated with the father’s satisfaction with family life (γ = − 0.036, p = .529). While the father’s FtoWC was not statically associated with the mother’s job satisfaction (γ = − 0.022, p = .712) not supporting H2c, the mother’s FtoWC was negatively associated with the father’s job satisfaction (γ = − 0.171, p = .005), thus supporting H2d. By contrast, the father’s job satisfaction was positively associated with the mother’s satisfaction with family life (γ = 0.090, p = .048) supporting H2e, while the mother’s job satisfaction was not statistically associated with the father’s satisfaction with family life (γ = 0.066, p = .178), therefore H2f was not supported.

Results from the comparison between actor and partner effects (Table 3) showed that the association of the mother’s family-to-work conflict and her own satisfaction with family life (actor effect) did not differ from the association of the father’s family-to-work conflict and the mother’s family life satisfaction (partner effect, p = .947). Similar results were found for the comparison of the association between mother’s job satisfaction and her own family satisfaction (actor effect) and the association between father’s job satisfaction and the mother’s family satisfaction (partner effect, p = .272); for the comparison of the association between father’s family-to-work conflict and the father’s family satisfaction (actor effect) and the association between mother’s family-to-work conflict and the father’s family satisfaction (partner effect, p = .112), and, for the comparison between the association of father’s family-to-work conflict and his own job satisfaction (actor effect) and the association for mother’s family-to-work conflict and the father’s job satisfaction (partner effect, p = .945). By contrast, the association between the father’s job satisfaction and his own family satisfaction (actor effect) was significantly higher than the association between the mother’s job satisfaction and the father’s family satisfaction (partner effect, p < .05). Likewise, the association between the mother’s work-to-family conflict and her own job satisfaction (actor effect) was significantly higher than the association between the father’s job satisfaction and the mother’s job satisfaction (partner effect, p < .05).

Most of the control variables did not affect the model significantly (Table 4). The family socioeconomic status positively affected the mother’s satisfaction with family life (γ = 0.097, p < .05) and job satisfaction (γ = 0.159, p < .01), while the mother’s age also positively affected her own job satisfaction (γ = 0.150, p < .01). Overall, the variance explained by the model was 31.2% in women and 33.6% in men.

Testing the mediating role of the job satisfaction

Lastly, this study tested the mediating role of both parents’ job satisfaction between both parents’ family-to-work conflict and satisfaction with family life (H3, actor and partner effects). The role of the father’s job satisfaction as mediator in the relationship between his own FtoWC and satisfaction with family life by a significant indirect effect obtained with the bootstrapping confidence interval procedure (standardized indirect effect = − 0.041, 95% CI = − 0.069, − 0.013) as the confidence intervals did not include zero (Table 3). This result supported H3a. Similarly, the role of mother’s job satisfaction as mediator in the relationship between her own FtoWC and satisfaction with family life was supported (standardized indirect effect = − 0.027, 95% CI = − 0.048, − 0.006), supporting H3b. Similar results were found for the role of the father’s job satisfaction as mediator in the relationship between the mother’s FtoWC and the father’s satisfaction with family life (standardized indirect effect = − 0.042, 95% CI = − 0.075, − 0.010), thus supporting H3e.

No other indirect effects of the parents’ job satisfaction were found, as the confidence intervals did include zero (Table 5). These findings did not support H3c, H3d, h3f and H3g regarding the mediating role of job satisfaction between both parents’ FtoWC and satisfaction with family life.

Discussion

The boundaries between work and family often overlap (Clark, 2000). These boundaries have blurred even more during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has resulted in higher family-to-work conflict for many workers, especially women (Frank et al., 2021). This study contributes to research showing how and why some aspects of the work and family domains overlap during a period of lockdown, a period that has led many workers to tending to increased family needs while working from home. Based on the spillover-crossover model (SCM, Bakker & Demerouti 2013), and following border theory (Clark, 2000) and conservation of resources theory (COR, Hobfoll 1989), we proposed that high demands that parents experience in their family sphere can interfere with their work, causing a loss of personal resources that affects both domains. Results of this study showed that, for different-gender dual-earner parents, a higher family-to-work conflict is linked to lower satisfaction with both their job and family life, while these two types of satisfaction are positively associated with one another. Consistent with SCM, the individual’s family-to-work conflict can also be associated with their partner’s satisfaction with their job and family life. However, these relationships are asymmetrical as significant crossovers between the work and family domains differed by gender.

As stated in the first set of hypotheses (1a to 1f), we expected that a higher resource loss derived from family-to-work conflict would be associated with lower satisfaction in the origin domain of this loss or strain (family), and the receiving domain (work, Amstad et al., 2011; Frone et al., 1992; Kuschel, 2017; Venkatesh et al., 2019). These propositions were supported: Family-to-work conflict was negatively associated with job and family life satisfaction, while the latter two were positively associated, for both mothers and fathers. These findings align with the idea of cross-domain associations (Frone et al., 1992), linking the family and work domains, and the matching hypothesis (Amstad et al., 2011), with a family-originated conflict linked to negative outcomes in the family domain. In both instances, individuals are experiencing a loss of personal resources (e.g., energy, time, moods, ten Brummelhuis & Bakker 2012) due to a family conflict interfering with work, which is associated with their satisfaction not only in the domain that is influenced by resource loss –work–, but also with satisfaction in the domain in which this loss originates –family–.

Although the associations between family-to-work conflict, and job and family satisfaction were significant for fathers and mothers, gender differences were observed in family-to-work conflict and family satisfaction; job satisfaction levels were statistically similar for both parents. On the one hand, mothers reported a significantly higher family-to-work conflict than fathers, which is in line with previous evidence, both before (Bilodeau et al., 2020; Kuschel, 2017) and during the pandemic (Frank et al., 2021). Regarding the latter, research conducted during lockdown periods at the beginning of the pandemic showed that women experienced a significant increase on household responsibilities compared to men (Farré et al., 2020). On the other hand, fathers reported higher family satisfaction than mothers. These gender differences may refer to distinct levels of integration of the work and family domains. For both fathers and mothers, family-to-work conflict can lead to resource loss negatively associated with job and family satisfaction. However, for mothers, conflict stemming from the family domain seems to take away more personal resources to invest in their family satisfaction.

Regardless of the above, and consistent with the matching hypothesis (Amstad et al., 2011; Drummond et al., 2017; Morr & Droser, 2020), fathers’ family-to-work conflict had a stronger association with his family satisfaction than with his job satisfaction. By contrast, for mothers, their family-to-work conflict had a stronger association with their job satisfaction than with their family satisfaction, which is in keeping with the cross-domain hypothesis (Amstad et al., 2011; Frone et al., 1992; Matei et al., 2021), suggesting gender differences regarding the matching and cross-domain hypotheses. This is an important finding because mothers experiencing more interference from their family to their work suggests that their priorities in the work-life interface might be shifting. Mothers’ interests and responsibilities in the work domain clashes with the cultural expectations that mothers must prioritize their personal resources to meet the demands of the family domain. As mothers remain held primarily responsible for solving family issues, the fulfillment of work responsibilities and their overall professional life may be undermined (Al-Alawi et al., 2021) more than for fathers. COR theory helps explain outcomes of family interference, for instance, considering that personal resources –such as time, attention, and concentration– that should be invested in the workplace are instead invested in family demands (Soomro et al., 2018). This strain for mothers might thus result in a more negative evaluation of their family life, whether because family dynamics are hindering their job performance, because mothers are unsatisfied with the role they would like to play in sustaining family life, or both. However, future research should continue to assess the extent of cross-domain hypothesis in mothers and the matching domain in fathers, and test whether this influence is typical in dual earner-couples with adolescent children, or it is a consequence of the pandemic. Indeed, the pandemic increase the potential for family-to-work conflict for both parents, but it has been suggested that if children require parental attention, for instance to help with school learning, the father’s job is likely to be prioritized while the mother’s job is likely to be interrupted or put off (Powell, 2020).

This study also tested crossover associations between these dual-earner parents (hypotheses 2a to 2f). It was proposed that parents in dual-earner couples experiencing higher family-to-work conflict would mutually influence their satisfaction in the work and family domains (Westman, 2001). We found that one parent’s family-to-work conflict and job satisfaction were indeed associated with the job satisfaction and family satisfaction of the other parent. However, per results from the APIM analysis, the relationships were not asymmetrical, in line with previous findings in the literature (Orellana et al., 2021a; Matei & Vîrgă, 2022). In this sense, resource loss derived from family-to-work conflict and low job satisfaction had differential associations with the job and family satisfaction based on the gender of the actor and the partner.

The crossover associations found align with the gender differences observed in intra-individual associations, supporting the differential priorities that men and women have for the work and family domains (Bilodeau et al., 2020). Specifically, related to partner associations in fathers, the more fathers experienced family-to-work conflict, the less satisfied mothers were with their own family life. The matching hypothesis is observed here for mothers in the family domain when the family-to-work conflict is experienced by her male partner. More research is needed into explanations for this finding, but it may be hypothesized that, as mothers are culturally considered in charge of the family domain, any interferences from this domain and their consequences (in the work and family domains) may be seen –by both mothers and fathers– as underperforming in their family role. In this sense, research suggests that women experience more stress when they feel that their spouses do not meet their work expectations due to obligations they have at home (i.e., family-to-work conflict, Smoktunowicz & Cieślak 2018), which in turn may negatively influence the mother’s family satisfaction. In addition, a second partner association found in fathers was that a higher job satisfaction in fathers was associated with a higher family satisfaction in mothers. It should be noted that in this study a greater proportion of fathers worked full time (45 h per week in Chile) and as employees compared to mothers. With this consideration, this crossover association might be explained by the appraisal of traditional division of labor, by a gendered segmentation of domains (Clark, 2000) in which fathers’ contributions to the household derives from being at work (Orellana et al., 2021a).

On the other hand, partner associations between mothers and fathers showed significant relations in the other way around. In another instance of cross-domains relationships, the mothers’ inter-role conflict originated in the family domain and affecting their work domain appeared to interfere with the father’s job satisfaction, but not with his satisfaction in the family domain. Dikkers et al., (2007) states that workers who face high job demands, such as a high workload or conflicting hours, may not be able to take on household chores, and the other spouse must get more involved. In our study, this dynamic would mean that mothers’ family-to-work conflict can interfere or cause strain in the work domain for fathers as they might have to get more involved in the home to compensate for the mothers’ conflict.

On the other hand, there was no crossover association between mothers’ job satisfaction and father’s family satisfaction. This finding aligns with those from Matei et al.’s (2021) meta-analysis on dyadic associations in couples, which showed that work-related variables (demands or resources) are not associated with the partners’ family well-being. These authors explained these null associations as based on the lack of transmission of work-related affectivity between partners and between domains. Nevertheless, our previous finding regarding the positive association between fathers’ job satisfaction and mothers’ family satisfaction goes against those null associations. We hypothesize that the cross-domain associations we found from job to family, from father to mother but not vice versa, derive from the gendered division of both domains. Mothers are perceived, and they perceive themselves, as the main caregiver of the family (Bilodeau et al., 2020), whereas, as stated above, it is considered that fathers take care of their family by working outside the home (Orellana et al., 2021a; Schnettler et al., 2020). The cultural expectations that mothers –and women in general– take on caregiving tasks have exacerbated during the pandemic (Frank et al., 2021; Jiménez-Figueroa et al., 2020; Orellana & Orellana, 2020), reinforcing that their job role is secondary to their family role. Hence, overall, mothers experience a double negative effect on their family life satisfaction, due to her own, and to their male partner’s family-to-work conflict. Another, more practical explanation for this result might be found in Schnettler et al.’s (2020) findings regarding life satisfaction in Chilean dual-earner couples. In this study there was a unidirectional crossover from a man’s job satisfaction to his partner’s life satisfaction, whereas his life satisfaction was not associated with his partners’ job satisfaction. This may also reflect the traditional gender-based demands and expectations (Westman, 2001), given the traditional role of men as the family’s main “breadwinner” it is likely that the family’s financial situation depends more on the father’s than on the mother’s job.

Although according to the APIM results, all actor effect associations were longer than partner effect associations in the relationship between family-to-work conflict, job satisfaction and family satisfaction, the comparison between actor and partner effects show that some of them did not differ statistically. That is, the mother’s family satisfaction is equally susceptible to her own family-to-work conflict as well as his partner’s, and vice versa. By contrast, while the mother’s family satisfaction is equally susceptible to her own job satisfaction as well as his partner’s, in the case of fathers they seem to be more susceptible to their own job satisfaction. Similarly, whereas the father’s job satisfaction is equally susceptible to his own family-to-work conflict as well as his partner’s, in the case of mothers, their job satisfaction seems to be more susceptible to their own family-to-work conflict. Therefore, our results are consistent with the findings reported by Yucel & Latshaw (2020) and by Schnetller et al. (2020) in that gender differences in actor and partner effect associations are related to the variables under study. The lack of statistical differences between actor and partner effect associations in mothers and fathers between family-to-work conflict and family satisfaction may reflect fathers being more actively engaged in family issues, as it has been reported previously in dual earner-couples (Drummond et al., 2017; Schnettler et al., 2020, 2022b). By contrast, the lack of differences in the actor’s and partner’s effect association between job satisfaction and the mother’s family satisfaction, while father’s family satisfaction is more susceptible to his own job satisfaction than of the mother’s job satisfaction may be associated to the fact that men are considered breadwinners for the family (Xu et al., 2019), particularly in Latin American countries where traditional family structures still prevail (Schnettler et al., 2021a). Furthermore, the lack of statistical differences between actor and partner effect associations between both member of the couple’s work-to-family conflict and the father’s job satisfaction, while mother’s job satisfaction is only associated with their own family-to-work conflict, may be associated with the unequal gender division of the unpaid work in countries with traditional family structures where mothers remain primarily responsible for solving family issues (Al-Alawi et al., 2021) despite having a paid job.

Lastly, the role of job satisfaction was tested as a mediator between family-to-work conflict and family satisfaction in both parents (hypotheses 3a to 3 h). Both the cross-domain and matching hypotheses describe work-family dynamics that might be unified by this mediating role. This hypothesis was further based on evidence that the family domain can contribute to job satisfaction (Ford et al., 2007; Venkatesh et al., 2019), and that job satisfaction (Al-Alawi et al., 2021; Wang & Peng, 2017) can be a mediator or moderator (Soomro et al., 2018) that buffers work-family conflict in either direction and for different outcomes, whether work-related (e.g., employee performance) or non-specific (e.g., depression). In this study, job satisfaction indeed showed a mediating role between family-to-work conflict and family satisfaction, but more consistently in an intra-individual manner, regardless of gender. That is, parents’ job satisfaction is a mechanism that allows the indirect transmission of strain from family-to-work conflict to family life satisfaction, as family strain generates a negative affective reaction towards the family domain.

As an interindividual mediator, job satisfaction once again depends on the gender of the actor and partner. In keeping with the previous results, only the fathers’ job satisfaction showed a mediating role between the mothers’ family-to-work conflict and the fathers’ satisfaction with family life. This finding thus complements those from previous crossover hypotheses, indicating that the mothers’ family-to-work conflict is indeed negatively associated with the fathers’ family life satisfaction indirectly, by first negatively affecting the fathers’ job satisfaction. This association may also be supported by negative affective reactions from fathers, due to the mothers’ stress and other negative reactions to her own conflict (Westman, 2001), and as these fathers invest in their family domain personal resources that were originally directed to their work domain. A remarkable pattern is that fathers, like mothers, also experience a double negative effect on family satisfaction, from their own, and their partner’s family-to-work-conflict. However, in the case of fathers, this effect from their female partner occurs via fathers’ own job satisfaction.

These findings may relate to the support gap found in dual-earner couples. According to Matei & Vîrgă (2022), husbands benefit from high support provided by their wives and may take it for granted or be less sensitized to additional support. On the contrary, as it may be the case for our findings, fathers’ job satisfaction may be more sensitive to mothers’ resource loss due to family-to-work conflict (i.e., mothers are less able to focus on their male partners’ needs, Matei & Vîrgă 2022). This pattern leads to hypothesize that mothers with a higher family-to-work conflict may rely more on the fathers, which for the latter may entail taking on more home and family responsibilities, thus decreasing both their satisfaction in both the work (due to lower engagement) and family domains (due to increasing demands). These results are an addition to literature showing the asymmetrical transmission of resources between dual-earner couples (Liang, 2015; Orellana et al., 2021a), while suggesting that spillover-crossover dynamics still depend on traditional gender roles and division of labor. All our findings suggest that the relationship between family-to-work conflict and job and family satisfaction has been quite complex during the pandemic period, thus future research should assess if these findings persist after the pandemic or are a consequence of it.

This study is not without its limitations, which should be addressed in future research. The study design was cross-sectional; the so-called effects derived from the Actor-Partner Interdependence Model propose causality, but they refer to associations and causality cannot be established. A second limitation is that findings in this study cannot be generalized to Chilean dual-earner parents with adolescents, given some of the characteristics of the sample. Namely, the sample was non-probabilistic and self-selected, representing a particular family structure with a relatively larger size compared to data of the Chilean 2017 National Census (an average of four family members, two children), and from a middle socioeconomic background. A third limitation is that, since the study design predates the pandemic, specific conditions related to lockdown measures were not assessed, namely whether parents were working from home or not; hence, the relationships found here cannot be related to job conditions. Another limitation is that the explicit involvement of adolescents in their parents’ family-to-work conflict was not assessed. Family-to-work conflict stem from behavioral difficulties in the workers’ children (Venkatesh et al., 2019), and adolescents present novel challenges to their parents related to their simultaneous demands of support and autonomy. Future studies will benefit from exploring the role that children play in their parents’ negotiations in the work-family interface. Moreover, more information is needed to establish other variables that contribute to the relationships found in this study; that is, those workplace conditions (e.g., those derived from formal employment vs. self-employment) and family dynamics that may be involved that strengthen or weaken these links for dual-earner parents. Lastly, the literature will benefit from studies addressing both the experiences of work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict during the pandemic, as these constructs indicate distinct sources of conflict but are but highly correlated with one another.

Implications and conclusion

Findings from this study pose theoretical, research and practical implications. From a theoretical standpoint, in this study the work and family domains are characterized as having permeable borders, and it was thus shown that the family-to-work conflict entails a loss of resources that can differentially affect job and family satisfaction in mothers and fathers, as individuals and as members of a dual-earner couple. These results highlight the need to consider gender dynamics when approaching the family-to-work conflict, as it was found that the matching hypothesis (family-to-work conflict linked to family satisfaction) was more strongly supported for fathers than for mothers, whereas the cross-domain hypothesis (family-to-work conflict linked to job satisfaction) was more strongly supported for mothers than for fathers. Regarding research, efforts should be directed to further exploring family-to-work conflict, particularly as a consequence of lockdown measures in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. In dual-earner parents, outcomes of interest for family-to-work conflict are those of a potentially dyadic nature, such as marital satisfaction, leisure time, and mental health issues. The role of variables related to having children should also be explored in how dual-earner parents manage their work-family interface, and how children of different ages (e.g., toddlers, adolescents) pose specific challenges for parents, and for mothers and fathers separately. Lastly, the previous research considerations should be expanded to families of different sizes and compositions to enrich the understanding of the family-to-work interface for a wider array of life conditions and populations.

In terms of practical implications, these findings underscore that family-oriented policies in the workplace (e.g., flexible schedules, considerations for leave of absence) can greatly improve the individual’s performance both in their job and in their family role. Of special interest is the understanding that the work and family spheres are in constant tension with one another throughout the day; that the dynamics in one sphere affects those of the other sphere; and that these family-work dynamics have an impact not only on the individual, but also on those close to them. This knowledge can inform public and workplace policies that address workers’ work-family balance and well-being. Furthermore, these policies require a gender perspective to deliver support, skills and motivation for men to get involved in their family life (i.e., to counter the cultural belief that men’s main contribution to the family is being absent while being at work), and for women to decrease their conflict between their family and work roles.

Taken together, the findings from this study contribute to the work-family interface literature by focusing on the role of family-to-work conflict in both job and family satisfaction at an inter-individual level. In this sample of different-sex dual-earner parents, both parents had similar levels of job satisfaction, whereas mothers reported more family-work conflict than fathers, and fathers reported more satisfaction with family life than mothers. Furthermore, family-to-work conflict showed a double negative effect on family satisfaction in these couples, as the individual’s family satisfaction depends on both their own, and on their partner’s, family-to-work conflict. Nevertheless, these experiences can vary by gender. Ultimately, dual-earner parents engage in their work and family roles constantly, and acknowledgment and support (between couple members, from the workplace, and at a structural level) for these work-family dynamics can lead to higher satisfaction in the family and job domains for workers and their partners.

Data Availability

Data and materials are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Agho, A. O., Price, J. L., & Mueller, C. W. (1992). Discriminant validity of measures of job satisfaction, positive affectivity and negative affectivity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 65(3), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1992.tb00496.x

Al-Alawi, A., Al-Saffar, E., Alomohammedsaleh, Z., Alotaibi, H., & Al-Alawi, E. (2021). A study of the effects of work-family conflict, family-work conflict, and work-life balance on Saudi female teachers’ performance in the public education sector with job satisfaction as a moderator. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 22, 486–503. Available at: https://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol22/iss1/39

Andrade, C., & Petiz Lousã, E. (2021). Telework and Work–Family Conflict during COVID-19 Lockdown in Portugal: The Influence of Job-Related Factors. Administrative Sciences, 11(3), 103. https://doi.org/10.3390/admsci11030103

Asociación de Investigadores de Mercado [AIM] (2016). Cómo clasificar los grupos socioeconómicos en Chile.http://www.iab.cl/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Presentaci%C3%B3n-final-AIM.pdf

Bakker, A., & Demerouti, E. (2013). The spillover-crossover model. In J. G. Grzywacz, & E. Demerouti (Eds.), Current issues in work and organizational psychology. New frontiers in work and family research (pp. 55–70). New York, NY, US: Psychology Press

Bakker, A. B., & Demerouti, E. (2016). Job Demands–Resources Theory: Taking stock and Looking Forward. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(3), 273–285. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000056

Bilodeau, J., Marchand, A., & Demers, A. (2020). Work, family, work–family conflict and psychological distress: A revisited look at the gendered vulnerability pathways. Stress and Health, 36, 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2916

Brough, P., Muller, W., & Westman, M. (2018). Work, stress, and relationships: The crossover process model. Australian Journal of Psychology, 70, 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12208

Chang, S. J., Van Witteloostuijn, A., & Eden, L. (2010). From the editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(2), 178–184. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.88

Clark, S. (2000). Work/family border theory: A new theory of work/family balance. Human Relations, 53(6), 747–770. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726700536001

De Clercq, D. (2020). “I can’t help at work! My family Is driving me crazy!” How family-to-work conflict diminishes change-oriented citizenship behaviors and how key resources disrupt this link. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 56(2), 166–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886320910558

De Clercq, D., Rahman, Z., & Haq, I. U. (2019). Explaining helping behavior in the workplace: The interactive effect of family-to-work conflict and Islamic work ethic. Journal of Business Ethics, 155, 1167–1177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3541-3

De Simone, S., Lampis, J., Lasio, D., Serri, F., Cicotto, G., & Putzu, D. (2014). Influences of work-family interface on job and life satisfaction. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 9(4), 831–861. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-013-9272-4

Dikkers, J. S. E., Geurts, S. A. E., Kinnunen, U., Kompier, M. A. J., & Taris, T. W. (2007). Crossover between work and home in dyadic partner relationships. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 48, 529–538. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00580.x

Drummond, S., O’Driscoll, M. P., Brough, P., Kalliath, T., Siu, O. L., Timms, C. … Lo, D. (2017). The relationship of social support with well-being outcomes via work–family conflict: Moderating effects of gender, dependants and nationality. Human Relations, 70(5), 544–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716662696

Easterbrook-Smith, G. (2020). By bread alone: Baking as leisure, performance, sustenance, during the COVID-19 crisis. Leisure Sciences, 43(1–2), 36–42, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2020.1773980

Emanuel, F., Molino, M., Lo Presti, A., Spagnoli, P., & Ghislieri, C. (2018). A Crossover study from a gender perspective: The relationship between job insecurity, job satisfaction, and partners’ family life satisfaction. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1481. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01481

Farré, L., Fawaz, Y., González, L., & Graves, J. (2020). How the COVID-19 lockdown affected gender inequality in paid and unpaid work in Spain.Iza.org.https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/13434/how-the-covid-19-lockdown-affected-gender-inequality-in-paid-and-unpaid-work-in-spain

Ford, M. T., Heinen, B. A., & Langkamer, K. L. (2007). Work and family satisfaction and conflict: A meta-analysis of cross-domain relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 57–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.1.57

Frank, E., Zhao, Z., Yang, Y., Rotenstein, L., Sen, S., & Guille, C. (2021). Experiences of work-family conflict and mental health symptoms by gender among physician parents during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open, 4(11), e2134315. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.34315

Frye, N. K., & Breaugh, J. A. (2004). Family friendly policies, supervisor support, work family conflict and satisfaction: A test of a conceptual model. Journal of Business and Psychology, 19(2), 197–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-004-0548-4

Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77, 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.77.1.65

Ghislieri, C., Molino, M., Dolce, V., Sanseverino, D., & Presutti, M. (2021). Work-family conflict during the Covid-19 pandemic: teleworking of administrative and technical staff in healthcare. An Italian study. La Medicina Del Lavoro, 112(3), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.23749/mdl.v112i3.11227

Gobierno Regional Región de O’Higgins (2020, June 19). Resolución exenta N° 3640-32-1571. Dispone Cuarentena comuna de Rancagua y Machalí.https://www.goreohiggins.cl/docs/2020/covid/3640-32-1571.pdf

Hagelskamp, C., & Hughes, D. L. (2016). Linkages between mothers’ job stressors and adolescents’ perceptions of the mother–child relationship in the context of weak versus strong support networks. Community Work & Family, 19(1), 103–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2014.998628

Hayes, A., & Preacher, K. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451–470. https://doi.org/10.1111/bmsp.12028

Hobfoll, S. E. (1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44(3), 513–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513

Hobfoll, S. E., Halbesleben, J., Neveu, J. P., & Westman, M. (2018). Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 5, 103–128. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104640

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jiménez-Figueroa, A., Bravo Castillo, C., & Toledo Andaur, B. (2020). Conflicto trabajo-familia, satisfacción laboral y calidad de vida laboral en trabajadores de salud pública de Chile. Revista de Investigación Psicológica, 23, 67–85

Karakose, T., Yirci, R., & Papadakis, S. (2021). Exploring the Interrelationship between COVID-19 Phobia, Work–Family Conflict, Family–Work Conflict, and Life Satisfaction among School Administrators for Advancing. Sustainable Management Sustainability, 13(15), 8654. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13158654

Kenny, D. A., Kashy, D. A., & Cook, W. L. (2006). Dyadic data analysis. Guilford press

Kinnunen, U., Feldt, T., Geurts, S., & Pulkkinen, L. (2006). Types of work-family interface: well-being correlates of negative and positive spillover between work and family. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 47, 149–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2006.00502.x