Abstract

Qualitative studies of lay people’s perspectives on facets of well-being are scarce, and it is not known how the perspectives of people with high and low levels of well-being dovetail or differ. This research explored the experiences of people with high/flourishing versus low/languishing levels of positive mental health in three cross-sectional survey design studies. Languishing and flourishing participants were selected in each study based on quantitative data from the Mental Health Continuum - Short Form as reported by Keyes et al. (Journal of Health and Social Behavior 43:207–222, 2002). Qualitative content analyses were conducted on written responses to semistructured open-ended questions on the what and why of important meaningful things (study 1, n = 42), goals (study 2, n = 30), and relationships (study 3, n = 50). Results indicated that well-being is not only a matter of degree—manifestations differ qualitatively in flourishing and languishing states. Similar categories emerged for what flourishing and languishing people found important with regard to meaning, goals, and relationships, but the reasons for the importance thereof differed prominently. Languishing people manifested a self-focus and often motivated responses in terms of own needs and hedonic values such as own happiness, whereas flourishers were more other-focused and motivated responses in terms of eudaimonic values focusing on a greater good. We propose that positive mental health can be conceptualized in terms of dynamic quantitative and qualitative patterns of well-being. Interventions to promote well-being may need to take into account the patterns of well-being reflecting what people on various levels of well-being experience and value.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Psychosocial well-being and psychopathology are two separate dimensions of mental health, a core construct in quality of life research, with diverse correlates as has been argued and empirically illustrated in diverse samples across the world (e.g., Keyes 2002; Keyes et al. 2008; Schutte et al. 2016; Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). Different degrees of psychosocial health have been conceptualized on the well-being dimension and were quantitatively described (e.g., Keyes 2002, 2013). Initially most of the theoretical and empirical research on psychosocial well-being focused on hedonic aspects such as positive emotions and satisfaction with life, but studies increasingly indicate the importance of the eudaimonic component for a more comprehensive understanding of well-being, including facets such as meaning, purpose in life, and social well-being (Baumeister and Landau 2018; Fowers et al. 2016; Fowers et al. 2010; Klein 2017; Morioka 2015; Vittersø 2016; White 2017; Wong 2012). A need for the combination of eudaimonic and hedonic components in conceptualizations and measurement (Baumeister et al. 2013; Henderson and Knight 2012; Huta and Waterman 2013; Sheldon et al. 2019) has also been highlighted. One integrated model is the Mental Health Continuum model of Keyes (2002), which presumes that mental health involves emotional, psychological, and social components. The model has been operationalized in the Mental Health Continuum (MHC) scale, with the 14-item Short Form version (MHC-SF; Keyes 2013; Keyes et al. 2008) being used most frequently.

Against the backdrop of the theoretical model, the MHC-SF distinguishes three levels of mental health or well-being, namely flourishing (high levels of well-being), languishing (low levels of well-being), with moderate mental health being in between. Several studies have explored the prevalence of the various levels of well-being in a variety of groups and investigated the concomitants thereof quantitatively (e.g., Keyes and Simoes 2012; Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2016). However, information on possible qualitative differences in manifestations of well-being on different levels of psychosocial health is lacking. Recently, scholars also advocated for doing more qualitative research in positive psychology to provide a deeper understanding of well-being (Hefferon et al. 2017).

The present study seeks to address this gap. In particular, we explored with open-ended semistuctured questions to flourishing and languishing participants in three different groups of adults, what the most important meaningful things, goals, and relationships were for them, as well as why those were important for them. The importance of meaningful experiences, goals, and relationships as facets distinguishing levels of well-being is supported by the findings of Talevich and colleagues (Talevich et al. 2017) of a hierarchical taxonomy of human motives in terms of meaning, agency, and communion. The following section will briefly introduce each of these as facets.

Meaning

The experience of meaning has been theorized as an important component of well-being (Ryff 2018; Ryff and Keyes 1995; Seligman 2011; Wang et al. 2018; Wong 2012) and has received increasing attention as a study area in positive psychology (George and Park 2016; Martela and Steger 2016). In general, meaning is conceptualized as peoples’ sense that their lives matter, that the world in which they live is comprehensible or coherent, and that there are possibilities to experience fulfilment that align with important values and opportunities for connectedness. Heine et al. (2006) contended that meaning in life refers to understanding who we are, our place in the world, and how we fit into the grand scheme of things.

Some empirical studies have focused on the importance of sources of meaning to provide a richer understanding of where it is that people find meaning in their lives (Delle Fave et al. 2013; Nell 2014a; Schnell 2011; Steger et al. 2013). Qualitative explorations of meaning that delve beyond categorizing sources of meaning (the “what”) to understanding motives underlying meaning (“why” identified sources provide meaning) have provided preliminary data to build a more detailed picture of individuals’ experience of meaning (Delle Fave et al. 2013; Nell 2014a). Qualitative studies have been identified as an important future study focus in the area of meaning (Steger et al. 2013). Quantitative research supports a positive and bi-directional relationship between meaning and well-being (Delle Fave et al. 2013), but very little qualitative research has been done exploring meaning and how it links to well-being. For example, it is not known how people high and low in well-being compare in where they find meaning and what the underlying reasons are for their identified meaning sources.

Goals

Despite some theoretical and conceptual differences about goals, many researchers contend that goals are expressions of a life purpose, and a future orientation reflecting states that people seek to obtain, maintain, or avoid (Brdar and Rijavec 2009; Emmons 2005; Thorsteinsen and Vittersø 2018). Different types of goal orientations are distinguished, such as mastery versus performance goals (Poortvliet and Darnon 2010), approach versus avoidance goal orientations (Elliot 1999), instrumental (means and ends separable) versus constitutive (means and ends inseparable) goal orientations (Fowers et al. 2010), and intrinsic versus extrinsic goals (Deci and Ryan 2000). Apart from these mostly intrapersonal theoretical goal perspectives, the interdependence of goal pursuits in life is coming to the fore as described in the Transactive Goal Dynamics Model (Fitzsimons and Finkel 2015) and illustrated in several empirical studies (see Feeney and Collins 2015 for an overview).

Goals and purposes are often used as linked or interchangeable constructs, and purpose is then also associated with meaning and taking action in the nomological network (e.g., Klinger 2012). However, these constructs also have unique denotations: Whereas goals usually refer to the “what” of striving, the “why” of striving is connected to purpose and meaning. Levels and attainment of meaningful goals and purposes are linked to well-being, and sometimes viewed as a major benchmark for the experience of well-being (Emmons 2003). Despite the proposed linkages of goals with purpose and meaning, we could not find any qualitative studies that investigate the differences and/or similarities of goals between individuals with high and low well-being. In addition to filling this gap, we also want to understand from individuals’ perspectives the connection between goals, purpose, and meaning.

Relatedness

There are many views and findings on the importance of positive relationships in human functioning and well-being, but few specific relational well-being theories. On a descriptive level, interpersonal relational well-being is characterized by, for example, mutual trust, companionship, support, emotional security, concern and caring, self-disclosure and sharing, positive reactivity, and moral action (e.g., Fowers et al. 2016; Reis and Gable 2015; Roffey 2012; White 2018). The centrality of relationships for the experience of meaningfulness was espoused in the “belongingness hypothesis” demonstrated in Baumeister and Leary (1995). Ryff and Singer (2008) reviewed empirical findings showing that the experience of loving relationships and purposeful living are linked to better recovery from illnesses, and also operate as protective and promotive mechanisms for health and well-being.

Although explicit relational well-being theories are limited, most multidimensional theories of well-being include a relational aspect, for example, Keyes’s (2002) flourishing model which includes psychological (Ryff 1989) and social (Keyes 1998) well-being, Seligman’s (2011) PERMA model, and the Self-Determination model of Deci and Ryan (2000). A new development is a specific interpersonal relational well-being model presented by Reis and Gable (2015) focusing on the quality of responsiveness. Another new development is a eudaimonic relationship scale validated by Fowers et al. (2016) in which the core qualities of relational well-being are conceptualized and operationalized in terms of relational giving, goal sharing, meaning, and personal growth. Various subfields of psychology such as developmental psychology, social psychology, personality psychology, family and marital science, positive psychology, as well as sociology, development science, and the relatively newly developing area of relational science offer some conceptualizations and empirical findings on the importance of positive relationships for well-being (e.g., Finkel and Simpson 2015; Fowers et al. 2016; Gable and Impett 2012; Lambert et al. 2013; White 2017).

Relatedness is mostly interpreted as referring to the interpersonal level, but it can also be conceptualized broader to include intrapersonal, interpersonal, social, transpersonal, and physical contextual levels. For example, a broader than interpersonal focus was taken by Prilleltensky (2001) stressing from a social psychology perspective, the interconnectedness of individual, interpersonal, and collective well-being. Helne and Hirvilammi (2015) also argued from a sustainable developmental perspective that human well-being and the ecosystem are interrelated and interdependent for long-term health and well-being, and thus taking into account that relatedness is broader than the interpersonal level and includes the contextual and natural environment.

Linked to the idea of multilevelness of well-being (e.g., Ng and Fisher 2013; Urata 2015) interconnectedness and interdisciplinary perspectives on relatedness and well-being are emerging, as well as empirical studies in this regard (e.g., Delle Fave et al. 2016; Delle Fave and Massimini 2015; Delle Fave and Soosai-Nathan 2014; Finkel and Simpson 2015). Delle Fave et al. (2016) showed the primacy of harmony and relational connectedness as core characteristics of happiness as experienced by lay people in various countries. The importance of interpersonal harmony for the experience of meaning and well-being in life was also indicated by Wang et al. (2018). Klein (2017) showed that prosocial behavior is linked to the experience of meaning in life on an intrapersonal level. Across many countries, empirical findings indicated that when individuals are asked what the most important things in their lives are, their answers most often refer to close interpersonal relations with partners, family, and close friends (Delle Fave et al. 2013; Delle Fave et al. 2016; Lambert et al. 2013).

It is however not yet known whether preferred relationships, patterns of relatedness, or the importance of a specific type of relationship differ between flourishers and languishers. In this study, the term “relationships” refers to the traditional notion of interpersonal relationships, whereas we use the term “relatedness” to refer to the broader inclusive notion of intrapersonal, interpersonal, and person-context links or interconnectedness.

The Present Study

This paper reports on three qualitative studies exploring possible similarities and differences between flourishing and languishing individuals with regard to their construals of meaning (study 1), goals (study 2), and relatedness/relationships (study 3). What follows is a description of the method used in all studies.

General Method

Overview

In each of the three studies, data were collected in a once-off cross-sectional survey design including quantitative measures as well as semistructured open-ended questions to which written responses were given. The questions in the three studies were on the most meaningful things (study1), most important goals (study 2), and most important types of relationships (study 3) as well as the reasons for the response in each case. In each of the studies, samples of flourishing and languishing participants were firstly selected based on their quantitative scores on the Mental Health Continuum – Short Form (MHC-SF) scale (Keyes et al. 2008). Thereafter, qualitative analyses were conducted per study on responses provided by the samples of flourishing and languishing participants.

Participants

For each of the three studies, data were collected cross-sectionally from various areas in South Africa implementing the snowball method of data gathering and aiming at maximum variation sampling (Bradshaw et al. 2017). Inclusion criteria stipulated that participants had to be older than 18 years, have a minimum of completed secondary school education, and had to be fluent in English. Most participants were employed in a variety of occupations. The demographic profile of the participants is provided below for each study.

Measures

Among other measures and relevant for the purpose of this research, all studies included a sociodemographic questionnaire, the MHC-SF, and a series of open-ended questions.

Sociodemographic Questionnaire

Sociodemographic questionnaires collected data on, inter alia, gender, age, and education level.

Mental Health Continuum – Short Form (Keyes et al. 2008)

The 14-item MHC-SF measures three components of positive mental health, namely emotional well-being (3 items), social well-being (5 items), and psychological well-being (6 items). Using a Likert scale ranging from “never” (0) to “almost every day” (5), respondents rate the frequency with which each statement has occurred during the previous month. Specific scoring criteria are given to distinguish flourishing, moderately mentally healthy, and languishing participants. Results from various countries, including North America (Westerhof and Keyes 2010), Argentina (Lupano Perugini et al. 2017), and South Africa (Keyes et al. 2008; Schutte and Wissing 2017) indicated good psychometric properties of the MHC-SF.

For this particular study, a three-factor bifactor confirmatory factor analysis model (Reise 2012) applied to the total combined sample (N = 1226) displayed adequate fit with the comparative fit index (CFI) obtaining a value of .953 and the root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) obtaining a value of 0.056 (90% confidence interval, 0.049; 0.062). Guidelines suggest that CFI-values above .950 indicate good fit and RMSEA values below 0.080 indicate reasonable fit (Byrne 2012). Model-based omega coefficients of composite reliability were calculated as described by Sánchez-Oliva et al. (2017). A value of 0.906 was obtained for the global mental health factor, while values of 0.640, 0.729, and 0.595 were obtained for the emotional, social, and psychological well-being subscales, respectively. The adequate fit of the bifactor confirmatory factor analysis model and the large reliability score for the global mental health factor support the use of scale total scores in this study.

Semistructured Open-Ended Question on a Specific Facet of Well-being

Each study involves a different semistructured open-ended question formulated in line with the methodology used by Delle Fave et al. (2011) in the Eudaimonic-Hedonic Happiness Investigation. The specific questions relevant to each study will be mentioned where the studies are presented below. Participants responded in writing.

Procedure and Data Analysis

The quantitative data from the validated MHC-SF were used in each study to purposefully select two groups or samples of participants, one exhibiting high levels of well-being (flourishing) and the other exhibiting low levels of well-being (languishing), thus targeting participants who possessed qualities that will help to find answers to the research questions. The written responses of participants to the semistructured questions were then qualitatively analyzed. The prevalence of people in South Africa who are flourishing has been found in previous studies to be much higher (ranging from 14 to 61%) than the languishing group (ranging from 1.5 to 9%, Wissing and Temane 2013). As it was expected that enough flourishing participants would be available to reach data saturation, participants in the relatively expected small languishing group were first identified and included in each study. A corresponding number of participants from the flourishing group were randomly drawn.

Following sequentially from initial quantitative selection of flourishing and languishing samples, the qualitative data were analyzed without a pre-existing coding frame, using a traditional content analysis approach (Hsieh and Shannon 2005; Krippendorff 2019). The process started with reading and rereading of the text to get some sense of the notions of participants, while noting some main points. The meaning units (each of the answers provided to each of the questions in the respective studies) were then shortened where applicable (for example, in the case of repetitions in the same answer) while retaining the core meanings. Then condensed meaning units were labeled by formulating codes or names, and similar ones were grouped into categories with short factual names as expressions of manifest content. For the answers to the “what” questions, categories were the highest level of abstraction. For the “why” questions, we then further created themes to describe the latent level motivations. The motive-themes were descriptive and could include verbs, adjectives, and adverbs.

Participants were added until no further categories and themes emerged. To check data saturation, that is, when no new categories or themes emerged, additional participants with low levels of psychosocial well-being (since all languishing participants were already included in the study, we added participants based on scores below the first tertile of the MHC-SF) were drawn, and then also an equal number of participants with high levels of well-being (in the flourishing category). For studies 1 and 2, no further categories or themes emerged from these additional participants, which confirmed that data saturation had been reached and the initial sample was therefore deemed sufficient. In study 3, new themes emerged in the low well-being group. Therefore, participants from the lower end of the moderately mentally healthy group were added to the languishing group until no new themes emerged and data saturation was reached. A corresponding number of flourishing participants were added and their responses also analyzed without new categories and themes emerging.

To increase credibility of findings, researcher triangulation was implemented by two coders independently analyzing the data for each study. One started with the flourishing group and the other with the languishing group with the aim of neutralizing possible coder bias when moving from a flourishing sample to a languishing sample, or vice versa in the analyses. Responses were coded by the third, fourth, and fifth authors for the three studies, respectively, and another qualified coder in each instance. The few divergent findings between coders per study were discussed, and consensus reached in conversation with the first two authors. The latter were also in particular involved in abstracting higher level themes. For the interpretation of findings, both quantitative (high versus low well-being) and qualitative data (emerging categories and motive-themes) were taken into account.

Trustworthiness

The guidelines for trustworthiness in all phases of planning, analysis, and reporting as described by Elo et al. (2014) were taken into account. In the planning phase, credibility was ensured by purposefully selecting samples of high and low well-being participants (as determined quantitatively with the validated MHC-SF) from a database collected with a maximum variation strategy (Bradshaw et al. 2017) in the various provinces of South Africa, and with specific inclusion criteria as indicated above. In this way, we hoped to make sense of how adults from South African samples experience important goals, meaningful things, and relationships. We wanted to understand more about the complexity of well-being as can be inferred from responses of lay adults with different levels of well-being as shown across findings from various eudaimonic constructs and explored in the three studies reported in this article. Content analysis, a flexible method not tied to a specific epistemology or theoretical perspective (cf., Braun and Clarke 2013), was conducted in an inductive and data-driven way. Codes and categories were identified on the (what) semantic level, and then also motive-themes on the latent (why) level where applicable in combining two or more categories. Dependability and conformability of findings were ensured by initial analysis and coding being conducted by two independent coders per study until data saturation had been reached, with one coder starting by analyzing the flourishers’ data and the other coder starting with the languishers. Coders read and reread the text while making notes, then moved to grouping codes into categories where indicated, and lastly making final thematic abstractions in the case of the answers to the “why” questions. This was a non-linear iterative process of revisiting codes, categories, and themes several times (cf. Erlingsson and Brysiewicz, 2017). The few discrepancies were discussed among coders and first two authors until consensus had been reached. Themes from the three studies (i.e., on meaning, goals, and relatedness) were then integrated, linked to theoretical perspectives, and possible implications indicated. The possibility of transferability of findings to similar groups is enhanced by careful description of participant selection, implementation of specific semistructured questions, description of the analysis process with an auditable trace, and explication of how connections were made between findings and conclusions. Trustworthiness was also supported by the fact that all contributors to this study are well schooled in positive psychology theories and approaches, as well as quantitative and qualitative research methodologies.

Ethical Considerations

In all three studies, trained fieldworkers obtained written informed consent from participants and ensured that participation was voluntary. Anonymity was ensured by separating the signed consent forms from the corresponding answer sheets and confidentiality considerations were upheld. The Health Research Ethics Committee of the North-West University, South Africa, approved the study from which data are reported in the present paper (approval number NWU 00002-07-A2).

Study 1: Meaning

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore what the most important sources of meaning were for people with high (flourishing) versus low (languishing) levels of psychosocial well-being, and what the motives underlying these meaning sources were.

Method

Participants

Forty-two participants (21 flourishing and 21 languishing) were selected from a large sample (N = 939) recruited with the snowball method from various geographic locations across South Africa. The flourishing group comprised 15 females and 6 males, and the languishing group 12 females and 9 males (including the extra participants to ensure data saturation). The age range was 18 to 64 years (M = 49, SD = 10.55 for flourishing participants; and M = 36, SD = 12.72 for languishing participants). A total of 14 participants in the flourishing group and 16 in the languishing group were tertiary-educated.

Measures

Apart from the sociodemographic questionnaire and the MHC-SF, two semistructured open-ended questions were used, namely “Please list the three things that you consider most meaningful in your present life” (sources of meaning) and “For each of them, please specify why it is meaningful (try to be as specific as possible)” (motives underlying those meaning sources).

Results and Discussion

Flourishing and languishing participants reported several similar categories or sources of meaning, such as relationships, religion, work, and health. Key differences emerged between flourishers and languishers in the motives underlying similar meaning sources. In the following portrayal of categories and motivations, therefore flourishing and languishing participants are indicated by a number ranging from participant PF1 to PF21, and PL1 to PL21.

Categories of Meaning Sources (Presented with Motives) for Flourishing and Languishing Participants

Below the categories of most meaningful things (important sources of meaning) are presented with indication of how these and the motives for the particular category differed between languishing and flourishing participants.

Relationships

were the most prominent source of meaning for both languishing and flourishing participants. These relationships were with family, the spouse, parents, children, and friends, with family being the most frequently mentioned for both groups.

The finding that relationships, particularly with family, were the most consistent source of meaning for both languishing and flourishing participants is in line with previous research across cultures (e.g., Delle Fave et al. 2011). It also supports findings by Debats (1999) who found relationships to be the most important source of meaning for both his psychiatric patient and non-patient groups. In Wong’s (2012) multidimensional meaning structure, social relationships are considered a precondition for meaning, with meaningful social relationships and social validation being considered as vital as oxygen.

Support was the most frequently mentioned reason for considering relationships as prime source of meaning for languishing participants, for example “[Family] They stand by my side” (PL6). For languishing participants, another reason for family as a source of meaning was because it provided a sense of identity, for example, family “defines” (PL10) or “complete[s]” (PL17) them, and “without my family I will not be me” (PL18). Although flourishing participants acknowledged support as one of the reasons why relationships are a source of meaning (e.g., “Family is always there and love you no matter what” [PF3]), the most often mentioned motivation in this group was that relationships provided participants with multifaceted positive experiences such as “joy” (PF10), “pride” (PF15), “share our blessings” (PF14), and “bring out the best in each other” (PF9).

Both languishers and flourishers deemed relationships as a source of meaning for the reason that relationships (and particularly family) provide ultimate meaning. This seemingly tautological response has been found in other studies (Delle Fave et al. 2013; Wissing et al. 2014) and could point to the fundamentality of relationships as a source of meaning, where participants are unable to separate the meaningful ends from the motivations for their meaningfulness (Fowers et al. 2010), specifically because relationships are a precondition of meaning (Wong 2012). The Relationality-Meaning model (Wissing 2014) proposes relational well-being as the bedrock for meaning in life.

Flourishers and languishers differed in the quality of motive-themes for relationships as meaning sources: Flourishing participants referred prominently to the “we” in relationships, reciprocal processes, and the sharing of positive affect in these relationships, whereas for languishing participants, support was the most cited reason for relationships being a source of meaning in life which alludes to own needs to be fulfilled.

Religion

was the second most mentioned source of meaning. For both groups, the underlying motivation was that religion was seen as a source of support. In addition, some flourishing participants identified the provision of coherence as a reason—religion provided a “manual” (PF10; PF5), “guidance” (PF12), and a way to “steer into a meaningful future” (PF20). Motives for religion as a source of meaning brought up metaphoric language such as God being “the rock we build on” (PL17) and “an anchor in life” (PF13).

Religion as an important source of meaning for both flourishers and languishers is in line with other research such as by Emmons (2003) and Schnell (2011). Some studies, however, have found that religion is a less important source of meaning compared with other meaning sources (e.g., Debats 1999). Delle Fave et al.’s (2013) study using data from seven countries also found that spirituality was generally not regarded as an important source of meaning, with South Africa being the notable exception. This differential finding is in line with other South African research (Nell 2014a; Wissing et al. 2014) and highlights that meaning can only be understood within the context of culture (Chao and Kesebir 2013).

The support mentioned by participants as the motivation for religion as a source of meaning was not the social support that is theorized to be an important factor in religion as a mediator to greater well-being (Diener et al. 2011), or the social support of a religious community helping to suggest meaning when global meaning has been challenged. Rather, the support described was transcendental in nature and implicit in this was a personal relationship with God. This vertical “relational” component of religion was important to both languishing and flourishing participants. It offers support for the view that “interconnectedness” is the “most basic starting point” and “very essence” of meaning in life (Delle Fave and Soosai-Nathan 2014, p. 39). The finding that some flourishing participants viewed religion as a source of meaning because of the sense of coherence it gave to their lives, dovetails with the analysis of Martela and Ryan (2016) indicating coherence as one of three main components of meaning. Coherence of course also implies a predictable and structured way of interconnectedness. The fact that coherence was only mentioned by flourishers, suggests that the role of religion in providing comfort or support versus coherence, and the interplay thereof with meaning and levels of well-being, warrant further investigation.

Work

was an important category that emerged for many in the flourishing group and was also described in far more positive terms than in the case of languishers. Some flourishing participants spoke about work in terms of a “calling” (PF6, PF7), “passion” (PF3, PF11), or “purpose” (PF3, PF16) that “fulfill[ed]” (PF3, PF16) them. For some of the flourishing participants, work was a source of meaning because it was an avenue for generativity, wanting to “pass it to others” (PF5) or “add value to the employees” (PF15). Only few of the languishing participants mentioned work as a source of meaning, and then the reasons had more to do with work as a basic need, with motivations like “grateful that I have a job” (PL7) or “I need money” (PL13). One languishing participant even mentioned the source of meaning as “free time away from work” (PL19).

Work as an important source of meaning was also noted by Delle Fave et al. (2013). As participants in the current study (except for one retiree and two without indication) were all employed in a variety of occupations or studying, it is a question why there was such a difference between languishing and flourishing participants in the frequency with which work was cited as a source of meaning. The reasons provided for the importance of work offer potential insights. The use of words like “calling,” “passion,” and “purpose” by some flourishing participants is suggestive of a particular kind of mindset towards work. Wrzesniewski et al. (1997) found that people who viewed their work as a calling had significantly higher levels of well-being than those who viewed their work as a career or job. Steger and Dik (2009) also found that people who approached their careers as a calling reported higher levels of meaning in life, life satisfaction, and career decision-making efficacy. In contrast to the flourishing participants, the few languishing participants who did mention work did so from the orientation of a job. When having a job orientation to work, people focus on the material benefits accrued from work and their work is seen as a means to a financial end that enables them to find enjoyment in time away from work (Rosso et al. 2010).

Other Minor Categories

Both flourishers and languishers indicated health as a source of meaning for similar reasons. Additionally, flourishers indicated peace as a source of meaning and motivated it, for example, as “Peace means that you are happy and you can focus on the important things in life” (PF1). A unique source and motivation for meaningfulness mentioned by flourishers was an explicit other-orientedness, for example, “My love for my fellow human beings … You cannot love God and not love those that walk life’s journey with you, whether they are in the same lane or a way off. We all have our struggles and our joys. Valuing each other enriches us” (PF10), and “Reaching out to others … gives me joy” (PF19). For languishers, escaping from stress was mentioned as a motivation for sources of meaning such as “music” and “freedom,” for example, “Relaxes me – is an escape” and “To get away from stress” (PL4 and PL14). The seemingly materialist response of “cell phone” as a source of meaning was actually motivated by a relational concern, “To maintain interpersonal relationships with friends” (PL21).

This study indicates that whereas many sources of meaning may look similar between flourishers and languishers, the reasons for the importance thereof reveal key differences within categories of meaning sources. Our findings lend some support to Nell’s (2014a) assertion that meaning is not contained in the source of meaning itself, but rather in the “process of exchange between the individual and the source of meaning” (p. 89).

Motive-Themes That Manifested Across Categories of Meaning Sources

As illustrated above, languishing and flourishing participants provided to great extent different reasons for the importance of a specific meaning source, but also showed some similarities. Below, the subarching and overarching motive-themes that played a role across two or more categories are summarily indicated.

Intrinsic Meaning and Value

Both languishers and flourishers deemed relationships as a source of meaning for the reason that relationships (and particularly family and religion as categories) provide ultimate meaning and anchor them in life.

Primacy of Relationship

Horizontal (interpersonal) and vertical (spiritual/religious) relationships emerged not only as fundamentally important sources of meaning for both flourishers and languishers, but it was also given as the motive for other categories of meaning sources, particularly in the case of flourishers. This points to the primacy of relationship as a motive-theme.

Sharing and Reciprocity

Flourishing participants prominently refer to the “we” in relationships, reciprocal processes, and the sharing of positive affect in these relationships, whereas for languishing participants, support was the most cited reason for the meaningfulness of relationships—thus less reciprocal and focused on own need fulfilment. This is shown in family as well as work as sources of meaning.

Personal Contributions and Rewards

Flourishing participants found meaning in contributing and being generative, and found fulfilment in work or family relationships. Also, for flourishers, the reasons for meaning sources sometimes mentioned “life” (“my life,” “happy life,” and “life in general”) which referred back to happiness and being able to do things that make them happy or are part of life. Languishing participants more often focused on the rewards they get in terms of support in relationships or money as reason for the importance of work.

Engagement and Exchange with Others and Environment

Flourishing participants were deeply involved and caring in relationships and also deeply engaged in their work, referring, for example, to it in terms of a passion or a calling. They thus experienced meaning in the engagement and exchange which is part of an in-between process. Languishers engaged with others and work based on fulfilment of basic needs such as support in relationships, or money as reason for the importance of work.

Coherence, Harmony, and Peace

Coherence and harmonious and positive mutuality in horizontal and vertical relationships and community contexts seem to motivate flourishers’ meaning sources.

The overarching motive-theme is the primacy of relatedness as conduit for meaning-making in various life domains because of its inherent value and provision of opportunities and resources for growth, joy, realization of values, support, and need fulfillment. The main difference between flourishers and languishers was as follows: Flourishers motivated the importance of relatedness in terms of the intrinsic value of relationships, enjoyment, mutuality, and value realization in engagement with others, work, and community, doing it mainly from a contribution perspective. Languishers motivated the experience of meaning in relatedness mostly in terms of the support and caring they receive, reflecting a scarcity and need fulfilment perspective.

Study 2: Goals

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore what the most important goals were for middle-aged adults with high (flourishing) versus low (languishing) levels of psychosocial well-being, as well as the reasons therefore.

Method

Participants

The goals of emerging adults and older adults may differ from those of people in the middle age years (Steger et al. 2009); therefore, the focus in this study was on a relatively homogenous middle age group of adults who are, from a developmental perspective, in a phase of life where rearing children and being engaged in work are major tasks. Participants for this study were languishing and flourishing South Africans between 35 and 64 years of age, selected from a large group (N = 568) recruited with the snowball method of data gathering in various geographic locations of South Africa. The languishing (n = 15, age M = 44, SD = 6.9) and flourishing (n = 15, age M = 47, SD = 7.4) groups consisted each of nine females and six males (including the extra participants to ensure data saturation). Of the languishing participants, five had secondary, six tertiary, and four post-graduate education. In the flourishing group, four had secondary, six tertiary, and five post-graduate levels of education.

Measures

Two semistructured open-ended questions were used apart from the sociodemographic questionnaire and the MHC-SF, namely “Please list the three most important future goals for you” and “For each of them, please specify why it is important.”

Results and Discussion

Findings yielded several similarities, but also clear differences between flourishing and languishing participants, especially in the reasons for the importance of selected goals. In the description below, flourishing participants are indicated as PF1 to PF15 and languishing participants as PL1 to PL15.

Categories of Most Important Goals (Presented with Motives) for Flourishing and Languishing Participants

Eight categories and two subcategories were found. These were relationships (with subcategories family and others), finances, approach to life (with subcategories personal well-being and well-being of others), health, work/career, self-development, spirituality, and leisure. These categories are described below with indications of how these and the motives for the importance of the specific goal differ between languishing and flourishing participants.

Relationships

Both the languishing and flourishing groups often referred to relationships in the important goals mentioned, but the groups differed in their goal focus and reasons for importance of goals. In the subcategory relationships—family, flourishing participants mentioned loving family relationships with partners, children, grandchildren, family togetherness, and the success of children. The reasons implied that good family relationships provided a safe and nurturing environment, relationship satisfaction, and fulfilment, for example, “Family keeps members intact” (PF11). The reasons for goals included wording such as “loving,” “satisfaction,” and “fulfillment,” for example, “Being in loving relationship with my life partner and kids, as this is a good base for feeling fulfilled” (PF1) and “Good relationships provide a safe and nurturing environment” (PF1). Languishing participants referred to better parenting, more family time, improved family relationships, family happiness, success of children, and relationships with children, teens, and grandchildren in their goals. Words such as “better,” “more,” and “improve” were used. The reasons for these goals included that life is rushed, that there is too little time, conflict with teens, and too much strife in the household. The reasons also stressed the value of relationships to languishing participants, for example, “My family is an extension of me” (PL9), “Give my children the support I never had” (PL5), and “Need more time with my family, life is so rushed” (PL2).

In the subcategory relationships—others, there were no responses from the languishing participants. The responses of flourishing participants included goals which entailed positive mentorship to family and others, time with family and others, and good working relationships. The motivations involved improving the lives of family, work colleagues, and others. This was reflected in responses such as “Being a mentor to children, grandchildren and others, I must point the way as a senior citizen” (PF9) and “In maintaining positive working relationships, workers will be more competent” (PF14).

Languishing participants were concerned with improving relationships and minimizing conflict in their goals and the motives therefore, whereas flourishing participants were focused on maintaining positive relationships with family and others. These findings resonate with earlier studies on well-being which found that those who have meaningful positive relationships with others are happier and healthier than those with less positive relationships (Roffey 2012). Related research posited that social affiliations are essential for human beings to flourish and experience eudaimonia (Fowers et al. 2010). Gable and Impett (2012) proposed that people routinely list successful close relationships among their most important life goals, and those who do not place social needs in the top tier of life goals have poorer mental and physical health.

Finances

Flourishing participants formulated goals of financial independence, financial security, highest business potential, children’s education, retirement provision, and future planning. The reasons for these goals included references to competence, self-actualization, and financial freedom, for example, “Because I know I can” (PF2) and “To pursue the things I enjoy in life” (PF1). Finances as goal refer for languishing participants to achieving financial freedom, to improve finances, to become financially stronger, retiring wealthy, and to be debt free. The reasons for goals related strongly to alleviating stress, not having enough time, struggling to cope financially, and being compelled to look at retirement options. The wording of goals again included “improve,” “become,” and “compelled,” and goal motivation responses included “Improve my finances” (PL5), “Become financially stronger” (PL10), and “Money problems cause bigger problems and stress” (PL5). Whereas flourishing participants approached finances from a competence, actualizing, developmental, and future directedness approach, languishing participants were more problem-focused and stress-avoidant in reasons for financial goals. The role of socioeconomic status in these findings needs to be further explored.

Approach to Life

In the subcategory related to personal well-being, languishing participants directed their goal focus and motives to personal well-being and appreciation of small things, life-balance, to enjoy life, happiness, and contentment. The reasons for these goals reflected “I must have balance in my life” (PL9) and “I don’t want to be unhappy and unsure” (PL13). Goal topics of the flourishing participants that focus on personal well-being included “Living the good life” (PF4) and “To have happiness” (PF13) and the reasons were to show appreciation and relieve stress.

The only response of the languishing participants in the subcategory of well-being of others was to do more charity work because “There was never time to do charity work” (PL15). The goals and motivations of flourishing participants in this subcategory consist of training educators, to be available for others, imparting life lessons, contributing to the lives of others, helping the needy, running an orphanage, teaching and mentoring, doing good, and “To care more about others around me” (PF7). The reasons mentioned were, for example, “To be the change I want others to be” (PF7), “To impart hope and encouragement” (PF9), and “Giving back to others” (PF12, PF15). There were more responses of flourishing participants with the goal to enhance the well-being of others and the community than to improve personal well-being. This suggests a tendency to focus on a greater good. Whereas the approach to life of the flourishing participants reflect meaning and purpose to contribute to others and the greater good, the responses of the languishing participants reflect an inward focus on personal well-being with mostly a hedonic approach of “I want to enjoy life” (PL10).

Health

Flourishing participants referred to health as goal in terms of maintaining and looking after health. The reasons for these goals were that health is a prerequisite to enjoy life, to achieve life goals, and to maintain life-long health. This reflects the striving for maintenance of something good and health as a resource for living, rather than as the sole aim of living, for example, “You need to be healthy to enjoy life” (PF11) and “Health helps you to achieve life goals” (PF13). In the case of languishing participants, health goals included being more active, greater fitness, weight loss, leading a healthier life, improving health and getting on top of, and overcoming health issues. The reasons for the goals included improving well-being and addressing specific health-related problems, for example, “I have depression and arthritis and am in a constant battle with pain and my mind” (PL11) and “Doing something about being overweight” (PL4). The reasons included words such as “more,” “improve,” and “overcome.” The goals of the languishing participants reflect a striving away from a position of negative health—they want to improve their health, whereas the flourishing participants are focused on maintaining existing good health substantiating that health benefits are associated with living a life rich in purpose and meaning and quality ties to others (cf., Ryff and Singer 2008).

Work/Career

The languishing participants set more goals under the work/career category than the flourishing participants, but these reflect mainly unhappiness with the current situation in the motivations. Success in work, a new job, a new career, an own business, as well as to remain in employment were the goals of the languishing participants. The reasons for these were, for example, “My job sucks” (PL9), “I need stability” (PL13), and “To boost my self-esteem” (PL6). The flourishing participants formulated work and work level progression as their goals “To move to another work level” (PF5). The reasons included “Work provides money and shelter” (PF4) and “Not to be redundant in one work level” (PF5), thus reflecting underlying motives related to the value of employment and the potential in new work levels. The languishing participants experience work as a means of survival to overcome pressures and challenges, striving towards career stability.

Self-development

The goals of languishing participants entailed personal development, completing studies, academic literacy, and “To improve academically” (PL10). The reasons involved personal and career growth, strengthening financial future and “To be a better me” (PL10). Self-development goals for flourishers were personal growth, further studies, and “To grow in myself and know myself better” (PF7). The reasons included to be more informed, personal satisfaction, and “After self-growth, I can understand the needs in others” (PF7). Even in the self-development goals of some flourishers, there is an indication of considering a greater good rather than merely personal well-being.

Other Categories

Spirituality was a goal category for both flourishers and languishers, but more often mentioned by flourishers. Living closer to God and spiritual growth were goals mentioned by languishing participants. Reasons for these goals included “To have an intimate relationship with God” (PL4). Spiritual growth, to serve God, and sharing God with all levels of society were goals for flourishing participants. The reasons were, for example, “For me to live is Christ” (PF12) and “To have the joy of the Lord” (PF12). Flourishers wishing to share beliefs on a wider societal level can reflect an inclusive and more eudaimonic orientation. Leisure as goal emerged in a few instances, and more for languishers than flourishers.

In summary, the most significant differences of goals and reasons therefore between languishing and flourishing participants were the eudaimonic, interpersonal, inclusive approach of the flourishing participants in contrast to avoidance, intrapersonal, and rectifying orientations of languishing participants. Whereas flourishing participants set goals and gave reasons therefore from a position of strength and maintenance of a positive status quo, languishing participants wanted to avoid something negative, for example, “I don’t want to be unhappy and discontent” (PL13). The flourishing participants formulated approach and future-orientated goals.

The specific wording of participants provides insights into deep experiences and differences between flourishing and languishing participants. The languishing participants used words such as “improve,” “overcome,” “more,” “better,” “boost,” “close,” and “stronger,” and phrases such as “job sucks” (PL9), “teen conflict” (PL4), “feel neglected” (PL10), “give support I never had” (PL5), “battle with pain and mind” (PL11), and “too much strife” (PL14). The flourishing participants use words such as “maintain,” “loving,” “growth,” “impart,” “contribute,” “satisfaction,” and “fulfilment,” and phrases such as “doing good” (PF15), “help the needy” (PF12), “giving back” (PF12), “point the way” (PF9), “making a difference” (PF7), and “I know I can” (PF7), which have a positive nuance. These differences underscore the importance of words/constructs for a deeper understanding of well-being as phenomenon as indicated by Carlquist et al. (2017). Flourishing participants revealed an altruistic, relational approach to life in goal setting and motivations, in contrast to more self-focused avoidant responses of languishing participants.

Motive-Themes That Manifested Across Goal Categories

As illustrated above, languishing and flourishing participants provided different reasons to the question why the specific selected goals were important to them, although some similarities were also shown. Below the subarching and overarching motive-themes, that played a role across two or more categories, are summarily indicated.

Relationships Are Important Goal Motivators

Interpersonal relationships (close and with others) as well as religious relatedness figured prominently in goal motivations of both languishing and flourishing participants. In the case of flourishing participants, the reason for goals often referred to relationships in terms of love, satisfaction, and fulfilment. Languishing participants motivated a relationship focus in goals mostly in terms of what is needed or missing, referring to motives such as better parenting, more family time, and improved family relationships. Languishing participants were concerned with improving relationships and minimizing conflict, whereas flourishing participants were more focused on maintaining and enjoying positive relationships with family and others when explicating the reasons for importance of the selected goal.

Life Orientation and Personal Contribution

Languishing participants directed the motives for goals more often to their personal well-being (from a comfort and need-perspective) and seldom referred to the well-being of others. The only reference to the well-being of others was to do more charity work for which they had never time before. Flourishers were strongly other-orientated in goal motivations in various domains of life such as personal relationships, community, and work, aiming to contribute to the well-being of colleagues, community fellows, and those in need. Flourishers more often aimed to enhance the well-being of others and the community than to improve personal well-being. But even when referring to personal well-being, they mentioned an inclusive reciprocity and an urge to show appreciation for others and life in general. This suggests a tendency to focus on a greater good. Whereas the motivations for selected goals reflect a life orientation of meaning and purpose in contributing to others and the greater good in the case of flourishing participants, the responses of the languishing participants reflected an inward focus on personal well-being with mostly a need fulfilment and hedonic approach.

Growth and Engagement

Flourishing participants were engaged with work, finances, and others for their own growth and that of others, because it provides a sense of competence, value realization, future directedness, and self-actualization. Languishing participants were also motivated towards growth and self-improvement, but mostly engaged from a problem-focused perspective referring to reasons of struggle to cope and avoidance of stress.

Change: Moving Towards Versus Moving Away from Something

In their goal-motivations, both flourishing and languishing participants referred in their motivations to change for the better. The motivations for selected goals of the languishing participants reflect a striving away from a negative position, for example, in health (mentioning reasons such as to lose weight, overcome health issues) and in work (for example, to feel better about themselves). In contrast, flourishing participants indicated mostly a move towards something positive, for example, maintaining good health, growing towards a next level in work or obtaining new skills and competencies, promoting the well-being of colleagues, and making plans for the future.

Harmony and Balance

Goal motivations of both flourishers and languishers reflect a quality of balance, for example, flourishers balancing own and others’ concerns, and a languishing participant just indicating that balance is needed.

The overarching theme is that selected goals are motivated by relational importance and the orientation and intention to move to a better place on the continuum of well-being on personal, interpersonal, and contextual levels, whether it is from a minus to neutral or neutral to plus. Flourishing participants motivated goals and behavior from a position of strength, development, and growth referring to self and the wider context, whereas languishing participants motivated goals often from a needs perspective and wanting to rectify or avoid something negative, while mostly focusing on the personal level.

Study 3: Relationships

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore what the most important types of relationships were for people with high (flourishing) versus low (non-flourishing/languishing) levels of psychosocial well-being, and the reasons therefore.

Method

Participants

Fifty participants (25 flourishing and 25 non-flourishing/languishing) were selected from a sample of N = 243 participants recruited with the snowball method of data gathering from various areas in South Africa, including the extra participants to ensure data saturation. The flourishing group comprised of 12 males and 13 females (aged M = 28, SD = 12.62), and the languishing group 5 males and 20 females (aged M = 25, SD = 10.96). In this study, several participants on the lower end of the moderately mentally healthy group had been included in the low well-being (languishing) group (to be 25 in total) in order to ensure data saturation. The fact that more participants were needed for the study on relationships is probably linked to the richness of content with regard to relational well-being aspects. For the sake of brevity, the high well-being group in this study will be designated as flourishing and the low well-being group as languishing. All participants completed at least secondary school. The number with completed tertiary education was not assessed for this group, but a notable number of participants came from tertiary educational contexts—hence the relatively younger mean ages than in studies 1 and 2.

Measures

Apart from a sociodemographic questionnaire and the MHC-SF, two qualitative semistructured open-ended questions were used to collect data. These questions were “Please list three kinds of most important relationships in your present life” and “For each of them, please specify why it is important and how this importance is manifested (try to be as specific as possible).”

Results and Discussion

A great deal of similarity in the types of most important types of relationships for flourishing and languishing groups were found, but the reasons why these relationships were deemed important, clearly differed. In the following descriptions, flourishing participants are referred to as participant PF1 to PF25 and languishing participants as participant PL1 to PL25.

Categories of Most Important Relationships (Presented with Motives) for Flourishing and Languishing Participants

For both groups, the most important types (categories) of relationships were close (horizontal) relationships, other (horizontal) relationships, and spiritual (vertical) relationships with subcategories in some of them. The categories of selected relational types are described below with indications of how the motives for the importance thereof differ between languishing and flourishing participants.

Close (Horizontal) Relationships

The reasons or motives for preferred close (horizontal) relationships mentioned (namely family, parents, spouse, children, siblings, romantic partner, work colleagues) mostly referred to positive affect or emotions, a sense of relatedness and support, and associations with growth/learning from close others. The reasons indicated by flourishing and languishing participants, however, differed in richness, resonance, and the integration of various facets. This will be illustrated below where the subcategories as described.

Family in General

The reasons for the importance of family as expressed by the flourishing group manifested various combinations of rich intertwined positive affections such as warmth, closeness, commitment, appreciation, mutual fulfilment and growth, being true to the self and joy which they associated with reciprocal support, sharing, and giving on an interpersonal level, for example, “[Family] I consider them to be inner core to my being they are my primary support structure and the core of my emotional wellbeing. Their success is my honour and reward. Whatever I give returns multiplied in love, joy and hope. To see them progressing towards a fulfilled life is sufficient reward for all the sacrifices made” (PF4). The reasons provided by languishing participants reflected positive affect, relatedness, opportunities for growth/learning from, and support. However, they referred more to the support and positives that they themselves gained from these relationships (e.g., happiness and guidance) while their reasons were concise and succinct. For example, “Family is very important because they provide support and understanding as well as love and encouragement” (PL19) and “Makes me happy to know people loves me” (PL15).

Parent(s)

The reasons of the flourishing group disclosed a positive secure attachment, high regard for (respect), support from, warmth, and closeness towards their parent(s). For example, “My mother is my everything. She is my role model and the strongest person that I know” (PF10). The languishing participants’ reasons highlighted the positive unconditional supportive gains from the relationship, for example, “[Parents] They support me” (PL17).

Spouse

Flourishing participants commented on the reciprocal interpersonal caring, loving, sharing of hope and social events/fun-times/enjoyable moments, mutual fondness, the fostering of meaning, protection, and lasting experiences. For example, “[My wife] We have fun and enjoy watching soccer and sports. We enjoy life together all the time. We love each other and our daughter” (PF24) and “[Wife and kids] Give my life meaning. I protect them, care for them and together we share love and hope. They also fill my heart with joy, happiness and pride” (PF15). The languishing participants added a more extrinsic motivator component, for example, “It gives life meaning; to be loved. It drives me” (PL5).

Children/Grandchildren

Both groups listed children. The flourishing participants reflected on their unconditional love for them, for example, “[Kids] Love them” (PF22), while the languishing participants listed the positive returns from the relationship like support, meaning, laughter, and pleasure, for example, “[My children and grandchildren] Always there to help me if I need them and to enjoy my grandchildren” (PL3) and “[Children] See them twice a month. Give my life meaning, joy, pleasure and laughter” (PL7).

Sibling(s)

Languishing participants listed sibling/s and reflected on relational gains such as receiving guidance and mentoring, for example, “[Sisters] They give guidance” (PL17) and “[My sister] She has always been someone I look up to” (PL23).

Romantic Partner

Flourishing participants reflected on in-depth friendship, commitment, companionship, support, and mutual love as reasons for relationships with romantic partners to be important. For example, “He is my best friend and is always there for me” (PF5) and “To love and to be loved is something a person needs” (PF18). The languishing participants’ responses reflected also a nearly engulfing dependency, for example, “He is my whole life” (PL4) and “Well me and my friend; we are like finger and a nail” (PL21).

Other (Horizontal) Relationships

Flourishing and languishing participants mentioned similar subcategories of other (horizontal) relationships (namely friends in general, close and distant friends, community/society, educators, pets). Only flourishers included community/society and only languishers included pets. The reasons why other (horizontal) relationships are important for both flourishing and languishing participants differ in nature and richness.

Friends in General

A sense of closeness, reciprocity, and an altruistic orientation was revealed by the flourishing participants who reflected on the interconnected warmth and closeness between them and friends, the positive attributes and growth opportunities, the sharing of positive friendships, and harmonized coherent values: “My friends and I always share the best moments, we (are) always there for one another and we always respect and encourage one another. We have a great relationship” (PF20), “[Friends] They share my values, morals and beliefs. We enjoy good times, learn from each other and share future dreams” (PF23). Languishing participants’ reasons focused more specifically on own intrapersonal gains and support in times of adversity, for example, “They support me and help carry me through tough situations or bad days” (PL18) and “They are always there to cheer you up and support you” (PL1).

Friends Close and Friends Distant

A distinction was made by languishing participants between close and distant friends although the reasons for the two subcategories in both cases reflected on the supportive gains and egoistic concerns from these relationships for themselves. For example, PL6 reported on close friends, “[Friends (Best friend)] I have someone I can share my biggest secret with. I don’t like keeping things to myself. Need to share with at least one person” and PL8 reflected on distant friends, “[Friends at church] The people at church care for me, they make me feel comfortable and invite me to dinner on Sunday evenings. Then we eat and tell jokes.”

Work Colleagues

Both the flourishing and languishing groups cited work colleagues as an important type of relationship. The flourishing participants highlighted as reason-theme the reciprocal loyal quality of assisting one another, growing and learning together regardless of the circumstances, for example, “[Coworkers] Help each other, learn and grow together, share hardship and prosperity” (PF14). The languishing participants’ motives focused on the supportive benefits or gains in adverse times that they get from colleagues: “[Colleagues] They give me a sense of hope and they care for me when I am not well. Sometimes they tell me jokes and try to entertain me” (PL8).

Community/Society

Only the flourishing participants mentioned community and society referring to reciprocal concern, mutual involvement and pro-social behavior in an extended environment outside the self and close others. For example, “[My relationship with the people in my community and the people I am interacting with every day] It is important to me to interact with other people so that we can help one another and add value to each other’s life” (PF10) and “[The society as a whole] So that there can be peace and harmony between me and all around me” (PF6).

Educators

Some flourishing and languishing participants reflected on educators being instrumental in the realization of success and personal growth. For example, PF13 reflected “To do better in class” and PL19 discerned “It is important for me to have a good relationship with my educators because they play a vital role in the success of my education.”

Pet(s)

Although a category with limited responses, pet(s) were noted by languishing participants. The quality of reasons provided hint to satisfaction of needs for closeness and to curb loneliness. For example, PL13 stated “Going home to my cat makes me feel like I have special care-take dependant relationship to rely on to feel less lonely” and PL20 reported “To remember that not only your opinion counts and to be able to take responsibility.”

Spiritual (Vertical) Relationships

Both groups perceived a spiritual/vertical relationship as sacred and the source of ultimate strength, but they differ in the nuances of the reasons provided. The flourishing participants expressed reasons related to a sense of connectedness, reliance, and closeness with the divinity who invests them with strength, endurance, fulfilment, optimism, guidance, and unconditional love. For example, PF4 indicated: “It is a lamp unto my feet and a light unto my path. Provides direction, wisdom and protection. He is the keeper of my spirit, soul and body. This has manifested in a peaceful demeanor, wise decision making, and a ‘leaning’ on a higher resource than myself. I understand agape love and that I have no need to perform to be loved and secure.” The languishing participants reflected in their motivations the unconditional gains associated with spiritual-relatedness but seemed to experience a more distant relational attachment since they showed discontent with their own ability to obtain closeness and made significant endeavors to try and attain closeness, for example, “He will always forgive me and love me even when I sometimes forget about him. I try to pray and read my Bible every day” (PL14) and “I so hardly want to have a great relationship with God and it is really very important to me so I try, but sometimes it doesn’t feel like I’m trying hard enough” (PL16). Empirical evidence supports the finding that religious faith and spiritual devotion fill people with hope and optimism rather than with despair (Kassin et al. 2014) and that transcendent closeness is associated with living the good life (Park 2015) and provides a clear framework of meaning in life (Nell 2014b).

Contextual Relatedness

Only flourishing participants referred to culture as an important relationship, with the motive being guidance, direction, or value-orienting and protection. For example, PF24 indicated “[My culture] I go to my family for guidance and to help when I need to know what is the best for me and my house. I also give guidance if they ask me and protect them.”

Intrapsychological Relationship

It is notable that only the flourishing participants mentioned an intrapersonal relationship as a category with the motivation referring to inner harmony among facets of the self that will promote personal growth, strengths, and self-awareness/knowledge. For example, according to PF6 “A good relationship with myself will ensure success because I’ll be loving all I do.” The latter highlighted the concept of an integrated self (Kuhl et al. 2015).

The findings from this study showed a great deal of similarity in the types of most important relationships for flourishing and languishing groups, but the reasons why these relationships were deemed important clearly differed between them. In general, mutual fulfilment, reciprocity and an orientation towards a greater good, and a sense of contribution, associated with eudaimonic well-being stood out for the flourishing group, whereas a personal need-fulfilment, more self-centered orientation characterized many responses of the languishers. The broader attention to relatedness on various levels seen in the experiences of flourishing participants support the notion of interconnectedness including intrapersonal, interpersonal, and transpersonal levels, and that awareness thereof may be associated with high well-being.

Motive-Themes That Manifested Across Types of Preferred Relationships Categories

As illustrated above, languishing and flourishing participants provided similar but also clearly different reasons for the importance of their selected types of important relationships. Below the subarching and overarching motive-themes, that played a role across two or more categories, are summarily indicated.

Intrinsic Value

Important relationships have an intrinsic value for both flourishing and languishing participants, and therefore they strive to maintain and improve them.

Sharing, Growing, Learning, and Enjoying Relatedness

Participants appreciated their selected most important relationships because they enjoy sharing the company of, and time spent with family and friends, learning from each other, and growing together. Motivations for various types of important relationships were described richly by flourishers in terms of positive affect, warmth, closeness, commitment, appreciation, mutual fulfilment, and growth. The reasons provided by languishing participants across various types of relatedness reflected positive affect, opportunities for growth/learning, comfort, and receiving support. They more often referred to the support and positives that they themselves gained from the relationships, whereas flourishing participants included more often mutuality and reciprocity in their motivations. Connectedness to context (culture) and pets were also appreciated because of a providing a sense of direction, belongingness, sharing, and comfort.

Giving and Receiving as Interconnecting Processes

Exchanges in the interconnecting process are valued by both flourishers and languishers. In the case of flourishing participants, a giving attitude is more prominent, and shown in a life orientation of appreciation and abundance and building a harmonized mutuality. In the case of languishing participants, a receiving attitude is more prominent in motivations and is shown in gratefulness for support and fulfilling dependency needs.

Personal Rewards

Languishing participants motivated the importance of relationships often in terms of the unconditional supportive gains when family and work colleagues pick them up when they feel down. Flourishing participants motivated the importance of relationships strongly in terms of the internal value thereof and the fact that it provided opportunities to grow.

Harmony

Flourishing participants refer to resonance, mutuality, and harmony in personal relationships as well as society as reasons for the importance of these relationships.

The overarching motive-theme for selecting various types of relationships reflects across categories an appreciation of the inherent value of relatedness, providing opportunities for the experience of meaning and purpose in life, as well as providing the opportunity for comfort, support, and stress reduction. For the flourishing group, mutual fulfilment, reciprocity and an orientation towards a greater good, and a sense of contribution, associated with functioning well stood out. In the case of the languishing group, personal need-fulfilment and a more self-focused feeling well orientation characterized the motivations for the importance of relationships.

General Discussion

Our findings suggest that well-being is not only a matter of degree but also a phenomenon that differs qualitatively on different levels of well-being, at least in the case of flourishing and languishing people. Three studies on different facets of functioning indicate that close relationships and relatedness in general figure strongly in experiences of meaning in life, important life goals, and quality of life, but it is also in this domain of life that the clearest differences between flourishing and languishing participants emerged. The present findings are in line with what is known about characteristics of psychosocial well-being, but add to it by showing that it is necessary to go beyond the surface of sources of meaning, specific goals, or the most important types of relationships to an understanding of the underlying motives and processes involved. Our findings may have implications for theory development, further research, and applications in practice in the field of well-being and quality of life.

Theoretical Implications: Towards Patterns of Well-being

The present findings empirically support characteristics of high well-being as described in theories of well-being, for example, people with high well-being experience positive affect, have a purpose and directedness towards a greater good, experience a positive engagement with work, enjoy positive relationships, and give and take social support. However, current theories do not take into consideration that the motivations of people on various levels of well-being differ qualitatively as found in the motive-themes emerging in the present study. For example, when languishers motivated the importance of relationships to them in terms of social support, it was mainly support for themselves from an intrapersonal perspective, whereas flourishers highlighted the reciprocal nature of support in important relationships. Well-being models need to recognize the dynamics involved in being well. To this end, we suggest that psychosocial health may be considered in terms of (qualitative and quantitative) dynamic patterns of well-being. Such patterns may exist of different configurations of characteristics of well-being which may also change depending on personal and contextual variables and processes (cf., Carlquist et al. 2017).

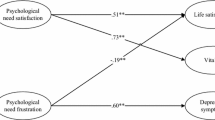

Dynamics Among Facets of Human Functioning

Our findings on different motivations for what flourishing and languishing people prefer, want, and do suggest that conceptualizations of well-being need to take the dynamics of intrapersonal, interpersonal, social, and contextual variables into account. On the intrapersonal level, affective, cognitive, conative, and behavioral facets are dynamically in interaction. In the present study, questions on the what and why of meaning tapped to a great extent into cognitive and value-related facets, goal questions linked to these but also included a strong conative, striving element that may direct behavior, and relatedness questions elicited responses especially referring to affective aspects, but also some conative, behavioral, and cognitive facets. For both flourishers and languishers, all of these components of human functioning played a role—but in different ways. Much more is to be learned in this regard.