Abstract

Malaysia plays a key role in education of the Asia Pacific, expanding its scholarly output rapidly. However, mental health of Malaysian students is challenging, and their help-seeking is low because of stigma. This study explored the relationships between mental health and positive psychological constructs (academic engagement, motivation, self-compassion, and well-being), and evaluated the relative contribution of each positive psychological construct to mental health in Malaysian students. An opportunity sample of 153 students completed the measures regarding these constructs. Correlation, regression, and mediation analyses were conducted. Engagement, amotivation, self-compassion, and well-being were associated with, and predicted large variance in mental health. Self-compassion was the strongest independent predictor of mental health among all the positive psychological constructs. Findings can imply the strong links between mental health and positive psychology, especially self-compassion. Moreover, intervention studies to examine the effects of self-compassion training on mental health of Malaysian students appear to be warranted.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Problematic Mental Health in Malaysian Higher Education

Malaysian higher education plays a key role in the rapidly developing region of Asia Pacific (Knight and Sirat 2011; Lee 2014), supported by more than 35,000 academic faculties (Wan et al. 2015). With the recent restructuring initiated by the “Malaysian Education Blueprint 2015–2025” scheme (Ministry of Higher Education 2012), research output of Malaysian universities has been expeditiously growing: between 2012 and 2016, Malaysia increased its scholarly output by 7.2%—one of the highest growth rates of all the researched countries (e.g., 4.6% in Australia, 4.2% in China, 3.6% Singapore; Elsevier 2018). Despite its successful academic achievement, Malaysian students suffer from poor mental health (Mey and Yin 2015; Ministry of Health 2016). The primary causes for their poor mental health are financial stress resulted from heightened tuition fees, academic pressure from increased workload, and general life stress associated with family matters (Gani 2016). To address mental health challenges, Malaysian government implemented the National Strategic Mental Health Action Plan, increasing access to mental health support and awareness (Ministry of Health 2016); however, its definite effects are yet to be seen. During these years of thriving academic development, the number of Malaysian students suffering from mental illness doubled from 10 to 20% (Bin Hezmi 2018). One cause for the increased mental illness was stigma around mental health issues (Ministry of Health 2016). Indeed, more than a third of Malaysians who suffered from mental health problems did not ask for help (Chong et al. 2013). Stigma and negative mental health attitudes are associated with, and predictors of poor mental health (Kotera et al. 2018a; b; d; e; f). For students who perceive mental health negatively, directly approaching mental health would not be effective, as they feel shame about engaging in such interventions (Kotera et al. 2018b, e, f). Instead, augmenting positive psychological constructs was suggested as an alternative approach to reduce mental health problems in UK student populations (Kotera et al. 2018b, e, f). However, to date these relationships have not been explored in Malaysian students in depth. Accordingly, this study aimed to explore positive psychological constructs, in relation to mental health of Malaysian students.

Positive Psychology for Mental Health

Since its development, high utility of positive psychology—the term coined by Abraham Maslow during 50s (Maslow 1954), studying happiness and well-being (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000)—has been consistently reported. While traditional psychology focuses on pathologies to be removed, positive psychology attends to one’s strengths and values to be nurtured (Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi 2000). Though still nascent (Kim et al. 2018), positive psychology has been introduced in Malaysian higher education, and the importance of potentiating their well-being has been recommended (Aziz et al. 2014). Positive psychological approaches, targeting flourishing mental health (i.e., high levels of mental well-being; Hone et al. 2014), are cost-effective prevention from mental health problems (Forsman et al. 2015; Kobau et al. 2011). Longitudinal studies noted the impacts of positive psychology on reduction of mood disorders. A 10-year observation of positive psychology and mental illness among American adults identified a relationship between an increase in positive psychological constructs and a decrease in mental illness (Keyes et al. 2010). In a Dutch 3-year study, flourishing mental health was predictor of large variance (28–53%) of mood disorders (Schotanus-Dijkstra et al. 2017). Intervention studies followed these findings. A randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining the effects of acceptance and commitment therapy noted that an increase in positive psychology outcomes concurred with a decrease in depression (Bohlmeijer et al. 2015). A web-based positive psychology intervention, targeting positive emotions, engagement, and meaning, enhanced pregnant women’s well-being and reduced depression (Corno et al. 2018). Further, an 8-week positive psychology training, focused on engagement and motivation, reduced PhD students’ mental distress (Marais et al. 2018). Among Malaysian students, the “three good things” exercise, where students recorded three good things that happened to them on each day over 2 weeks, improved their well-being and reduced their mental distress (Noor et al. 2018). Though some reported these associations were moderate (Weich et al. 2011), significant linkages between positive psychology constructs and mental health have been reported.

Engagement, Motivation, Self-compassion, and Well-being

One positive psychological construct that is particularly important in higher education is academic engagement (hereafter “engagement”) because of its positive relationships with diverse student outcomes: their mental health (Liébana-Presa et al. 2014; Rogers et al. 2017), attainment (Casuso-Holgado et al. 2013; Neel and Fuligni 2013), and intrinsic motivation (Armbruster et al. 2009; Bicket et al. 2010). Academic engagement relates to how much students are willing to make an effort in their academic work (e.g., knowledge and skill acquisition) (Newman 1992). Unsurprisingly, student engagement was associated with mental health and resilience (a strong protective factor of mental health; Trompetter et al. 2017) among 410 students in Australia, one of the neighboring countries of Malaysia (Turner et al. 2017). The relationships between academic engagement and student mental health have been found in other countries as well (Datu 2018; Suárez-Colorado et al. 2019). However, these engagement relationships have not been explored in Malaysian students.

Mental health is also related to intrinsic motivation—a key correlate of engagement (Baard et al. 2004; Bailey and Phillips 2016; Locke and Latham 2004). Intrinsic motivation is a type of motivation that contrasts with extrinsic motivation in the self-determination theory (SDT), one of the most established motivation theories (Deci and Ryan 1985). SDT holds that each individual has an inherent tendency to express their psychological energy into self-actualization and social adjustment (Deci and Ryan 1985). Intrinsic motivation can be expressed in activities that are inherently interesting and fulfilling (i.e., undertaking the activity itself is a reward); on the other hand, extrinsic motivation can be observed in activities that are means to an end, such as money and status. Intrinsic motivation is associated with positive outcomes such as better performance (Baard et al. 2004), well-being (Bailey and Phillips 2016), life satisfaction (Locke and Latham 2004), prosocial behavior (Gagne 2003), and ethical judgment (Kotera et al. 2018c). Contrariwise, extrinsic motivation is associated with negative outcomes such as burnout (Houkes et al. 2003), shame (Kotera et al. 2018a), depression (Blais et al. 1993), limited performance (Vallerand 1997), and unethical judgment (Kotera et al. 2018c). In higher education particular, students’ intrinsic motivation was related to academic performance (Khalaila 2015) and meaningfulness (Utvær 2014). However, these relationships of intrinsic motivation have not been thoroughly investigated in Malaysian students.

Self-compassion has been receiving increasing attention in mental health research for its association with mental health (Ehret et al. 2015; Kotera et al. 2018b, d, e, f; Muris et al. 2016). Self-compassion—being kind and understanding to one’s weaknesses and inadequacies (Gilbert 2010)—ameliorates mental distress by cultivating resilience (Trompetter et al. 2017). Self-compassion is strongly associated with better mental health (Ehret et al. 2015; Hayter and Dorstyn 2014; Muris et al. 2016), and also a key predictor of good mental health in UK students (Kotera et al. 2018f).

Lastly, mental well-being (hereafter “well-being”) is central in positive psychology (Slade 2010). A shift from treating mental illness to promoting mental well-being has been implemented at the policy level in mental health–aware countries such as Canada (Mental Health Commission of Canada 2009) and the UK (Department of Health 2009), because of the high relevance between those two constructs. A 2-year longitudinal study investigated the Malaysian students undergoing the recent educational restructure also reported the concomitant changes of mental health and well-being (Mey and Yin 2015).

Although these findings highlighted strong relationships between mental health and positive psychological constructs, no study to date has explored the relationships between mental health and positive psychology comprehensively. Further, how strongly each positive psychological construct is related to mental health has not been investigated in depth. Accordingly, this study aimed to explore these relationships and elucidate the relative contribution of each positive psychological construct to mental health in Malaysian students.

Methods

Participants

Participants had to be 18 years old or older, and a student of a Malaysian university. An opportunity sampling of 160 undergraduate students majoring in humanities subjects were approached by tutors’ announcements in their classes, and 153 (121 females, 31 males, 1 unanswered; RNGage = 18–27, Mage = 21.24, SDage = 1.59 years) completed the scales regarding mental health, engagement, motivation, self-compassion, and well-being. Students taking a study break at the time of the study were excluded from the study. Majority of them were Malaysian (143 Malaysians, eight Bangladeshis, and one unanswered). No participation incentive was offered. All the participated students filled out the participation consent prior to responding to the scales. This study was conducted along with another study that explored mental health attitudes and shame about mental health problems in the same cohort of students. The findings from the other study are reported elsewhere.

Materials

The Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21) was used to evaluate their mental health. This 21-item scale is a short form of DASS-42 (Lovibond and Lovibond 1995) classifying mental health problems into depression, anxiety, and stress (seven items each) on a 4-point Likert scale (“0” being “Did not apply to me at all” to “3” being “Applied to me very much or most of the time”). Items include “I felt that I had nothing to look forward to” for depression, “I felt I was close to panic” for anxiety, and “I found it difficult to relax” for stress. DASS-21 had high internal consistency (α = .87–.94; Antony et al. 1998). For the purpose of this study, the global DASS-21 score was calculated to appraise the level of overall mental health (Antony et al. 1998).

Engagement was assessed using the Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students (UWES-S), a 17-item scale appraising the degree students feel active and confident towards their academic activities (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). The three subscales of UWES-S correspond to vigor (six items including “I feel strong and vigorous when I’m studying or going to class”), dedication (five items including “I find my studies full of meaning and purpose”), and absorption (six items including “Time flies when I am studying”), rated on a 7-point Likert scale (“0” being “Never” to “6” being “Always (everyday)”). Vigor pertains to energy that leads to a great amount of effort in one’s studies determinedly; dedication considers one’s commitment to academic work; and absorption relates to positive immersion in one’s academic work (Schaufeli et al. 2002). UWES-S had high internal consistency (α = .63–.81; Schaufeli and Bakker 2004). In this study, the average of the total score for the engagement measure was used (Schaufeli and Bakker 2004).

Motivation was examined using the Academic Motivation Scale (AMS; Vallerand et al. 1992), consisting of 28 items considering three types of motivation categorized into seven subtypes: (i) amotivation, (ii) extrinsic motivation (external, introjected, and identified regulation), and (iii) intrinsic motivation (to know, to accomplish, and to experience stimulation). Students are asked why they go to university, and respond to items (e.g., “I don’t know; I can’t understand what I am doing in school” for amotivation, “In order to have a better salary later on” for extrinsic motivation, and “Because I experience pleasure and satisfaction while learning new things” for intrinsic motivation), which are responded on a 7-point Likert scale (“1” being “Does not correspond at all” to “7” being “Corresponds exactly”). AMS demonstrated adequate to high internal consistency (α = .62–.91; Vallerand et al. 1992).

For self-compassion, Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form (SCS-SF; Raes et al. 2011), a shortened version of the Self-Compassion Scale (Neff 2003) was employed. This 12-item 5-point Likert scale (“1” being “Almost never” to “5” being “Almost always”) includes “When something painful happens I try to take a balanced view of the situation,” and the scores on the negative items (1, 4, 8, 9, 11, and 12) are reversed. Internal consistency of SCS-SF was high (α = .86; Raes et al. 2011).

Lastly, well-being was measured using the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (SWEMWBS; Stewart-Brown et al. 2009), a seven-item scale, shortened from the original 14-item version (Stewart-Brown and Janmohamed 2008). Items are positively worded (e.g., “I’ve been thinking clearly”), responded on a 5-point Likert scale (“1” being “None of the time” to “5” being “All of the time”). SWEMWBS had high internal consistency (α = .85; Stewart-Brown et al. 2009).

Procedure

Collected data were screened for outliers and the assumptions for parametric tests. First, correlation analyses were performed to explore the relationships between mental health, engagement, motivation, self-compassion, and well-being of Malaysian students. Second, multiple regression analyses were conducted to evaluate how much each variable could explain the variance in mental health. Lastly, mediation analysis was performed to examine whether the strongest predictor was mediated by another variable. The correlation and regression analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS 25. Process macro 3 (Hayes 2017) was used for mediation analysis, with 5000 bootstrapping re-samples and bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for indirect effects.

Results

Relationships Between Mental Health, Engagement, Motivation, Self-compassion, and Well-being

No outlier was identified, using the outlier labeling rule (Hoaglin and Iglewicz 1987). Because mental health, extrinsic motivation, amotivation, and well-being were not normally distributed (Shapiro–Wilk, p < .05), all the subscales were square-root-transformed. Pearson’s correlation was calculated to explore the relationships between mental health, engagement, motivation, self-compassion, and well-being (Table 1).

Mental health was associated with engagement (r(151) = − .22, p = .008), amotivation (r(151) = .40, p < .001), self-compassion (r(151) = − .60, p < .001), and well-being (r(151) = − .49, p < .001), while it is not associated with demographics (gender r(151) = .08, p = .30; age r(151) = .01, p = .88), intrinsic motivation (r(151) = − .05, p = .53), and extrinsic motivation (r(151) = .08, p = .34). Well-being was related to gender (r(151) = − .26, p = .001), mental health (r(151) = − .49, p < .001), engagement (r(151) = .39, p = .001), intrinsic motivation (r(151) = .29, p < .001), and self-compassion (r(151) = .52, p < .001).

Predictors of Mental Health

Multiple regression analyses were conducted to explore the relative contribution of engagement, amotivation, self-compassion, and well-being (significant correlates; predictor variables) for their mental health (Table 2). Multicollinearity was of no concern (VIFs < 10). Engagement, amotivation, self-compassion, and well-being were entered as predictor variables, and mental health was entered as an outcome variable. Age and gender were not entered, as these were not significantly related to mental health. These predictor variables accounted for 47% for mental health, a large effect size (Cohen 1988). Engagement and amotivation were positive predictors, whereas self-compassion and well-being were negative predictors for mental health. Self-compassion was the strongest predictor of mental health among all the predictor variables.

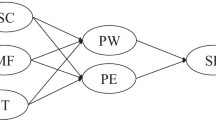

Further, a mediation analysis was performed to examine whether the strongest prediction of self-compassion (predictor variable) for mental health problems (outcome variable) was mediated by well-being (mediator variable), using model 4 in the Process macro (parallel mediation model; Hayes 2012) (Fig. 1).

Parallel mediation: self-compassion as a predictor of mental health problems, mediated by well-being. The confidence interval for the indirect effect is a BCa-bootstrapped CI based on 5000 samples. Direct effect (total effect). Values attached to arrows are coefficients indicating impacts. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001

The total and direct effects of self-compassion on mental health problems were significant (total b = − 7.00, t(151) = − 9.25, p < .001; direct b = − 6.94, t(150) = − 9.11, p < .001), whereas the indirect effect of self-compassion on mental health problems through well-being was not (b = − .06, BCa CI [− .32, .12]). Well-being did not mediate the effect of self-compassion on mental health problems: Self-compassion independently predicted the variance in mental health problems.

Discussion

This study explored relationships between mental health, engagement, motivation, self-compassion, and well-being of Malaysian university students. Their mental health was associated with engagement, amotivation, self-compassion, and well-being. Those significant correlates of mental health predicted 47% (a large effect size) of mental health, and were all significant predictors of mental health. Self-compassion was the strongest independent predictor.

Mental health was related to all the positive psychological constructs, except for intrinsic motivation. These significant relationships were in line with previous research (Kotera et al. 2018b; Mey and Yin 2015; Rogers et al. 2017) and may imply the importance of positive psychology for mental health in Malaysian students. Contrary to previous findings, intrinsic motivation was not associated with mental health. This may be explained by a type of passion (i.e., intrinsic motivation) students experience towards their academic work. If they are passionate to study, because of social acceptance (e.g., parents’ approval), that could create obsessive passion, which could damage their well-being (Vallerand et al. 2003). Because obsessive passion is derived from outside of their control, the activities that are attached to social acceptance can take exaggerated importance, harming the other areas of life (i.e., they cannot stop doing the activity). As one of the primary reasons for mental health problems in Malaysian students was family matters (Gani 2016), some students might have had this type of passion, who could score high in intrinsic motivation but also high in mental health problems. On the other hand, harmonious passion—an autonomous internalization of the activities into their identity—was positively associated with well-being and negatively associated with mental distress (Vallerand et al. 2003). Future research should explore types of passion, in relation to mental health of Malaysian students. Moreover, a consideration of cultural acceptance for intrinsic motivation may be needed. Intrinsic motivation presumes that each individual has inherent proclivity to express their psychological energy for self-actualization and social adaptation, which can be more resonated with the Western individual cultures than the Asian collective cultures. Indeed, some motivation studies have been done with Asian populations (e.g., Israel; Khalaila 2015); however, a cultural fit of intrinsic motivation in highly collective cultures such as Malaysia and Indonesia has not been explored yet (Hofstede et al. 2010). As an understanding of “self” is different in between an individual culture and collective culture (Markus and Kitayama 1991), how intrinsic motivation is related to mental health can be also different in these two types of cultures. Comprehensive perceptions of these types of motivation (i.e., intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation) should be investigated in depth.

Engagement, amotivation, self-compassion, and well-being were associated with, and predictors of mental health. These four constructs predicted 47% of the variance in mental health, indicating a large effect size. Consistent with previous research, these constructs were also strongly related to mental health in Malaysian students. Considering their negative attitudes towards mental health (Chong et al. 2013), this can imply great clinical usefulness: augmenting these positive psychological constructs may be more effective to reduce mental distress, than directly targeting mental health symptoms of Malaysian students (as positive psychological approaches can bypass their negative mental health attitudes). As recent health policies endorsed (e.g., in Canada; Mental Health Commission of Canada 2009, and in the UK; Department of Health 2009), potentiating positive psychology, while considering the cultural characteristics (Marecek and Christopher 2017; Noda 2012; Singh and Groll 2015), should be also recommended in Malaysian students.

Among all the predictor variables, self-compassion was the strongest independent predictor of mental health. As reported in other student populations (Kotera et al. 2018b, e, f; Neely et al. 2009; Ying 2009), self-compassion was also important for Malaysian students’ mental health. This may suggest that providing self-compassion training to this student group may be useful, as it can result in better self-care and mental health (Dunne et al. 2016). One effective way to implement this type of training may be to embed it in the orientation stage, because informing students of common mental distress, and how to cope with it, in the beginning of their studies could protect them from the forthcoming academic stress (Law 2010). Further, such information about mental health care could prevent students from delaying help-seeking, leading to better clinical outcomes (Reavley and Jorm 2010). Additionally, this type of sessions can benefit tutors too, as enhanced compassion was associated with better mental health in a tutor population (Jennings and Greenberg 2009). Future research should evaluate the effects of self-compassion training on mental health of Malaysian students.

Although this study offers useful insights into student mental health in Malaysia, there are several limitations to be noted. First, students were recruited via opportunity sampling from one university, which restricts the generalizability of the study findings. Second, the scales used were self-report, which limits the accuracy of the student responses for social desirability bias (Latkin et al. 2017). Lastly, because it was a cross-sectional study, the causal direction of the relationships cannot be ascertained. Longitudinal studies would be useful to identify the causality and to develop interventions.

Although Malaysian universities successfully grew their academic impacts rapidly, mental health of Malaysian students remains challenging. This study explored the relationships between their mental health and positive psychological constructs. Academic engagement, amotivation, self-compassion, and well-being were associated with, and predicted 47% of variance in mental health. Intrinsic motivation was not related to mental health. Self-compassion was the strongest independent predictor of mental health among all the positive psychological constructs explored. Findings can imply the strong links between mental health and positive psychology, especially self-compassion, and a need for further research into passion. Moreover, intervention studies to examine the effects of self-compassion training on mental health of Malaysian students appear to be warranted.

References

Antony, M. M., Bieling, P. J., Cox, B. J., Enns, M. W., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment, 10(2), 176–181. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176.

Armbruster, P., Patel, M., Johnson, E., & Weiss, M. (2009). Active learning and student-centered pedagogy improve student attitudes and performance in introductory biology. CBE Life Sciences Education, 8(3), 203–213. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.09-03-0025.

Aziz, R., Mustaffa, S., Samah, N. A., & Yusof, R. (2014). Personality and happiness among academicians in Malaysia. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 4209–4212. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SBSPRO.2014.01.918.

Baard, P., Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (2004). Intrinsic need satisfaction: a motivational basis of performance and well-being in two work settings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34(10), 2045–2068. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02690.x.

Bailey, T., & Phillips, L. (2016). The influence of motivation and adaptation on students’ subjective well-being, meaning in life and academic performance. Higher Education Research and Development, 35(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1087474.

Bicket, M., Misra, S., Wright, S. M., & Shochet, R. (2010). Medical student engagement and leadership within a new learning community. BMC Medical Education, 10, 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-10-20.

Bin Hezmi, M. A. (2018). Mental health a major concern in coming years among Malaysian students? Retrieved from https://people.utm.my/azril/mental-health-a-major-concern-in-coming-years-among-malaysian-students/. Accessed 9 Dec 2018.

Blais, M., Brière, N., Lachance, L., Riddle, A., & Vallerand, R. (1993). L’inventaire des motivations au travail de Blais. [Blais’s work motivation inventory]. Revue Québécoise de Psychologie, 14, 185–215.

Bohlmeijer, E. T., Lamers, S. M. A., & Fledderus, M. (2015). Flourishing in people with depressive symptomatology increases with acceptance and commitment therapy. Post-hoc analyses of a randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 65, 101–106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2014.12.014.

Casuso-Holgado, M. J., Cuesta-Vargas, A. I., Moreno-Morales, N., Labajos-Manzanares, M. T., Barón-López, F. J., & Vega-Cuesta, M. (2013). The association between academic engagement and achievement in health sciences students. BMC Medical Education, 13(1), 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-13-33.

Chong, S. T., Mohamad, M. S., & Er, A. C. (2013). The mental health development in Malaysia: history, current issue and future development. Asian Social Science, 9(6), 1. https://doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n6p1.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Corno, G., Etchemendy, E., Espinoza, M., Herrero, R., Molinari, G., Carrillo, A., Drossaert, C., & Baños, R. M. (2018). Effect of a web-based positive psychology intervention on prenatal well-being: a case series study. Women and Birth, 31(1), e1–e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.06.005.

Datu, J. A. D. (2018). Flourishing is associated with higher academic achievement and engagement in Filipino undergraduate and high school students. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(1), 27–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-016-9805-2.

Deci, E., & Ryan, R. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behaviour. New York: Plenum.

Department of Health. (2009). New horizons. Towards a shared vision for mental health. Consultation. London: Author.

Dunne, S., Sheffield, D., & Chilcot, J. (2016). Brief report: self-compassion, physical health and the mediating role of health-promoting behaviours. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(7), 993–999. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316643377.

Ehret, A., Joormann, J., & Berking, M. (2015). Examining risk and resilience factors for depression: the role of self-criticism and self-compassion. Cognition and Emotion, 29(8), 1496–1504. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2014.992394.

Elsevier. (2018). Malaysia - Research Excellence And Beyond. Retrieved from https://www.elsevier.com/research-intelligence/campaigns/malaysia-research-excellence-and-beyond. Accessed 9 Dec 2018.

Forsman, A.K., Wahlbeck, K., Aaro, L.E., Alonso, J., Barry, M.M., Brunn, M., Cardoso, G…. Värnik A. (2015). Research priorities for public mental health in Europe: recommendations of the ROAMER project. European Journal Public Health, 25(2), 249–54. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cku232

Gagne, M. (2003). The role of autonomy support and autonomy orientation in prosocial behavior engagement. Motivation and Emotion, 27(3), 199–223.

Gani, A. (2016). Tuition fees ‘have led to surge in students seeking counselling’. Guardian. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/education/2016/mar/13/tuition-fees-have-led-to-surge-in-students-seeking-counselling. Accessed 16 Jan 2019.

Gilbert, P. (2010). The compassionate mind: a new approach to life’s challenges. Oakland: New Harbinger.

Hayes, A. F. (2012). PROCESS: a versatile computational tool for observed variable mediation, moderation, and conditional process modeling [White paper]. Retrieved from http://www.afhayes.com/. Accessed 16 Dec 2018.

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach. New York: Guilford.

Hayter, M. R., & Dorstyn, D. S. (2014). Resilience, self-esteem and self-compassion in adults with spina bifida. Spinal Cord, 52(2), 167–171. https://doi.org/10.1038/sc.2013.152.

Hoaglin, D., & Iglewicz, B. (1987). Fine-tuning some resistant rules for outlier labeling. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 82(400), 1147–1149. https://doi.org/10.2307/2289392.

Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: software of the mind. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Hone, L. C., Jarden, A., Schofield, G. M., & Duncan, S. (2014). Measuring flourishing: the impact of operational definitions on the prevalence of high levels of wellbeing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 4(1), 62–90.

Houkes, I., Janssen, P., de Jonge, J., & Bakker, A. (2003). Specific determinants of intrinsic work motivation, emotional exhaustion and turnover intention: a multisample longitudinal study. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 76(4), 427–450. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317903322591578.

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of Educational Research, 79(1), 491–525. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308325693.

Keyes, C. L. M., Dhingra, S. S., & Simoes, E. J. (2010). Change in level of positive mental health as a predictor of future risk of mental illness. American Journal of Public Health, 100(12), 2366–2371. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.192245.

Khalaila, R. (2015). The relationship between academic self-concept, intrinsic motivation, test anxiety, and academic achievement among nursing students: mediating and moderating effects. Nurse Education Today, 35(3), 432–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2014.11.001.

Kim, K., Doiron, M., Warren, H. A., & Donaldson, S. (2018). The international landscape of positive psychology research: a systematic review. International Journal of Wellbeing, 8(1), 50–70. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i1.651.

Knight, J., & Sirat, M. (2011). The complexities and challenges of regional education hubs: focus on Malaysia. Higher Education, 62(5), 593–606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9467-2.

Kobau, R., Seligman, M. E., Peterson, C., Diener, E., Zack, M. M., Chapman, D., & Thompson, W. (2011). Mental health promotion in public health: perspectives and strategies from positive psychology. American Journal of Public Health, 101(8), e1–e9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2010.300083.

Kotera, Y., Adhikari, P., & Van Gordon, W. (2018a). Motivation types and mental health of UK hospitality workers. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 16, 751–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-9874-z.

Kotera, Y., Conway, E., & Van Gordon, W. (2018b). Mental health of UK university business students: relationship with shame, motivation and self-compassion. The Journal of Education for Business. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2018.1496898.

Kotera, Y., Conway, E., & Van Gordon, W. (2018c). Ethical judgement in UK business students: relationship with motivation, self-compassion and mental health. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 17, 1132–1146. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-018-0034-2.

Kotera, Y., Gilbert, P., Asano, K., Ishimura, I., & Sheffield, D. (2018d). Self-criticism and self-reassurance as mediators between mental health attitudes and symptoms: attitudes towards mental health problems in Japanese workers. Asian Journal of Social Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12355.

Kotera, Y., Green, P., & Sheffield, D. (2018e). Mental health attitudes, self-criticism, compassion, and role identity among UK social work students. British Journal of Social Work. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy072.

Kotera, Y., Green, P., & Van Gordon, W. (2018f). Mental wellbeing of caring profession students: relationship with caregiver identity, self-compassion, and intrinsic motivation. Mindfulness and Compassion, 3(2), 7–30.

Latkin, C. A., Edwards, C., Davey-Rothwell, M. A., & Tobin, K. E. (2017). The relationship between social desirability bias and self-reports of health, substance use, and social network factors among urban substance users in Baltimore, Maryland. Addictive Behaviors, 73, 133–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ADDBEH.2017.05.005.

Law, D. W. (2010). A measure of burnout for business students. Journal of Education for Business, 85(4), 195–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832320903218133.

Lee, J. T. (2014). Education hubs and talent development: policymaking and implementation challenges. Higher Education, 68(6), 807–823. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9745-x.

Liébana-Presa, C., Fernández-Martínez, E., Gándara, A., Muñoz-Villanueva, C., Vázquez-Casares, A. M., & Rodríguez-Borrego, A. (2014). Psychological distress in health sciences college students and its relationship with academic engagement. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 48, 715–722.

Locke, E., & Latham, G. (2004). What should we do about motivation theory? Six recommendations for the twenty-first century. Academy of Management Review, 29(3), 388–403. https://doi.org/10.2307/20159050.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales (2nd ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

Marais, G. A. B., Shankland, R., Haag, P., Fiault, R., & Juniper, B. (2018). A survey and a positive psychology intervention on French PhD student well-being. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 13, 109–138. https://doi.org/10.28945/3948.

Marecek, J. & Christopher J.C. (2017). Is positive psychology an indigenous psychology? In N.J.L. Brown, T. Lomas, & F.J. Eiroá-Orosa (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of critical positive psychology (pp. 84–98). London: Routledge.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98(2), 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224.

Maslow, A. (1954). Motivation and personality. New York: Harper.

Mental Health Commission of Canada. (2009). Toward recovery & well-being. Calgary: Author.

Mey, C., & Yin, C. J. (2015). Mental health and wellbeing of the undergraduate students in a research university: a Malaysian experience. Social Indicators Research, 122(2), 539–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0704-9.

Ministry of Health. (2016). Press statement by Minister of Health Malaysia. Author. Retrieved from http://www.moh.gov.my/english.php/database_stores/store_view_page/22/451. Accessed 9 Dec 2018.

Ministry of Higher Education. (2012). Public Institutions of Higher Education (PIHE). Official portal of Ministry of Higher Education. London: Author Retrieved from http://www.mohe.gov.my/portal/en/institution/pihe.html. Accessed 9 Dec 2018.

Muris, P., Meesters, C., Pierik, A., & de Kock, B. (2016). Good for the self: self-compassion and other self-related constructs in relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression in non-clinical youths. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 607–617. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0235-2.

Neel, C. G.-O., & Fuligni, A. (2013). A longitudinal study of school belonging and academic motivation across high school. Child Development, 84(2), 678–692. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01862.x.

Neely, M. E., Schallert, D. L., Mohammed, S. S., Roberts, R. M., & Chen, Y.-J. (2009). Self-kindness when facing stress: the role of self-compassion, goal regulation, and support in college students’ well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 33(1), 88–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9119-8.

Neff, K. D. (2003). Self-compassion: an alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860309032.

Newman, F. M. (1992). Student engagement and achievement in American secondary schools. New York: Teachers College Press.

Noda, F. (2012). Is psychiatry universal across the world?: possibility of culture-based psychiatry in Asia and Asian-pacific. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 4. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12006.

Noor, N., Abdul Rahman, N. D., & Mohamad Zahari, M. I. (2018). Gratitude, gratitude intervention and well-being in Malaysia. The Journal of Behavioral Science, 13(2), 1–18.

Raes, F., Pommier, E., Neff, K. D., & Van Gucht, D. (2011). Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(3), 250–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.702.

Reavley, N., & Jorm, A. F. (2010). Prevention and early intervention to improve mental health in higher education students: a review. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 4(2), 132–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7893.2010.00167.x.

Rogers, A., DeLay, D., & Martin, C. (2017). Traditional masculinity during the middle school transition: associations with depressive symptoms and academic engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 46, 709–724. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-016-0545-8.

Schaufeli, W., & Bakker, A. (2004). Utrecht Work Engagement Scale preliminary manual. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

Schaufeli, W., Salanova, M., Gonzalez-Roma, V., & Bakker, A. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3, 71–92. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326.

Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., ten Have, M., Lamers, S. M. A., de Graaf, R., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2017). The longitudinal relationship between flourishing mental health and incident mood, anxiety and substance use disorders. The European Journal of Public Health, 27(3), ckw202. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw202.

Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: an introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5.

Singh, B., & Groll, D. (2015). Cultural competency training in graduate medical education. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 7, 1–35.

Slade, M. (2010). Mental illness and well-being: the central importance of positive psychology and recovery approaches. BMC Health Services Research, 10, 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-10-26.

Stewart-Brown, S., & Janmohamed, K. (2008). Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS) user guide version 1. Warwick: Warwick Medical School.

Stewart-Brown, S., Tennant, A., Tennant, R., Platt, S., Parkinson, J., & Weich, S. (2009). Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS): a Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish Health Education Population Survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-15.

Suárez-Colorado, Y., Caballero-Domínguez, C., Palacio-Sañudo, J., & Abello-Llanos, R. (2019). The academic burnout, engagement, and mental health changes during a school semester. Duazary, 16(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.21676/2389783X.2530.

Trompetter, H., de Kleine, E., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2017). Why does positive mental health buffer against psychopathology? An exploratory study on self-compassion as a resilience mechanism and adaptive emotion regulation strategy. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41, 459–468.

Turner, M., Scott-Young, C. M., & Holdsworth, S. (2017). Promoting wellbeing at university: the role of resilience for students of the built environment. Construction Management and Economics, 35, 707–718.

Utvær, K. (2014). Explaining health and social care students’ experiences of meaningfulness in vocational education: the importance of life goals, learning support, perceived competence, and autonomous motivation. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 58(6), 639–658. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2013.821086.

Vallerand, R. (1997). Toward a hierarchical model of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 271–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60019-2.

Vallerand, R., Pelletier, L., Blais, M., Briere, N., Senecal, C., & Vallieres, E. (1992). The academic motivation scale: a measure of intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation in education. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 52(4), 1003–1017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164492052004025.

Vallerand, R. J., Blanchard, C., Ve, G., Mageau, A., Koestner, R., Ratelle, C., … Marsolais, J. (2003). Les Passions de l’A ′ me: on obsessive and harmonious passion. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(4), 756–767. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.4.756.

Wan, C. D., Morshidi, S., & Dzulkifli, A. R. (2015). The idea of a university: rethinking the Malaysian context. Humanities, 4, 266–282.

Weich, S., Brugha, T., King, M., McManus, S., Bebbington, P., Jenkins, R., … Stewart-Brown, S. (2011). Mental well-being and mental illness: findings from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey for England 2007. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(1), 23–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.091496.

Ying, Y.-W. (2009). Contribution of self-compassion to competence and mental health in social work students. Journal of Social Work Education, 45(2), 309–323. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2009.200700072.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Yasuhiro Kotera and Su-Hie Ting declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Malaysia) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). Informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to being included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Kotera, Y., Ting, SH. Positive Psychology of Malaysian University Students: Impacts of Engagement, Motivation, Self-Compassion, and Well-being on Mental Health. Int J Ment Health Addiction 19, 227–239 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00169-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00169-z