Conclusion

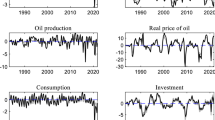

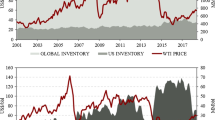

In this article, we propose a consistent view on the recent oil-price history based on fundamental data and economic theory. We sum up: After the turn of the century three major stylized shocks have hit market. First, the demand curve has shifted fight outwards, mainly driven, as extensively reported in the media, by sustained growth in China and other Asian Countries. Second, supply disruptions in countries with low extraction costs (Iraq and Venezuela) have shifted the supply curve to the left. Third, we show that speculators adjust their inventories in order to take advantage of predictable price fluctuations and play themselves a major role in the price formation. Optimal storage theory implies that aggregate inventories are negatively related to the oil price and positively to the volatility of supply and demand shocks.

We provide evidence that the political events in the last years have increased volatility and induced the inventory curve to shift right outwards. We analyze in a graphical framework the interaction of all these shocks and conclude that speculators have caused the oil price to overshoot in the short run its long-run fundamental value. However, this is not at all attributable to market failure or the harmfulness of speculators. In fact, the opposite is true. Speculators have in general a dampening effect on the oil price. The record oil price in the very recent history is partly a consequence of speculators maintaining or building-up inventories to cope with the supply and demand shocks to come. Hence, high prices represent a short-term toll for future price stability.

It follows from our analysis that the oil price is expected to fall towards its long-term mean, provided that no further shocks hit the economy and, critically, the oil supply. As we saw, this prediction is consistent with the observed prices in the futures markets. Also in terms of future price volatility, the outlook is rather upbeat. The increased inventory levels held by speculators will cushion the spot market against fluctuations in natural supply and demand and limit the degree to which the currently high underlying volatility will translate into higher price volatility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Endnotes

See HAMILTON (1983, 1988a, 1988b, 1996, 2003), HOOKER (1996), and MORK (1989), among others Overall, these papers conclude that there is a strong statistically significant relationship between oil prices and output and that positive shocks In the oil price impact the economy in a much stronger way than negative shocks The structural relationship estimated in HAMILTON (2003) gives a telling perspective of the potentnal consequences of today’s oil-market development For instance, an onl pnce of 50 dollars will on average induce a negatwe contribution to next year output of −15%.

Much important research on commodity pricing is based on the assumptnon of a stochastic convenience yield. See, for example, the work of Brennan (1991) and Gibson and Schwartz (1990). While this approach lends itself naturally when developing models for hedging or optnon pricing, it cannot be used to understand what is happening on a fundamental level

Section 2 2 will describe in more detail oil reserves, including strategic stocks held by governments. However, given the small volatility of these stocks, they can be ignored for our purposes

For a formal proof of th,s argument, see Lemma 4 in Deaton and Laroque (1992) and Proposition 8 in Routhledge et al. (2000).

A functional relatlonshap follows from the property that expected returns from holding inventories depend negatively on the aggregate level of inventorues, since thins guarantees that for moderate price levels there exist for each current pnce a single level of inventories where the expected rate of return from holding stocks of oil net of storage costs is equal to the risk-free rate A level of zero inventories obtains as a corner solution if the price is higher than a given threshold. A full scale model would include some mild technical conditions to ensure that the expected future price level is a monotonous function of the prevailing price level Explicitly taking this into account would be beyond the reach of this short, qualitative paper.

The assumption of risk-neutrality serves to simplify the analysis. None of our results change qualitatively by giving up this assumption.

The US Energy Information Administration reports for the period 1990–2000 average annual proportional storage costs of 20%, corresponding to 4–5 dollars per barrel per year

See William and Wright (1989) for a discussion We speak of backwardation when the spot price is higher than the forward price. Backwardated markets are a sign of tight supply. Backwardation creates an incentive for firms to reduce their supphes The opposite situation, when the spot price is lower than the forward price is called contango. Contango indicates oversupply

References

BRENNAN, M J and E S SCHWARTZ (1985) “Evaluating natural resource investments”, Journal of Business, 58, pp. 135–157.

CHAMBERS, M J. and R E BAILEY (1996) “A theory of commodity price fluctuations”, Journal of Political Economics, 104, pp. 924–957

DANTHINE, J-P. (1977): “Martingale, market efficiency and commodity prices”, European Economic Review, 10, pp 1–17.

DEATON, A and G. LAROQUE (1992) “On the behavior of commodity prices”, The Review of Economic Studies, 59, pp. 1–23.

DEATON, A. and G. LAROQUE (1996): “Competitive storage and commodity price dynamics”, Journal of Political Economy, 104, pp. 896–925

GIBSON, R and E S. Schwartz (1990) “Stochastic convenience yield and the pricing of oil contingent claims”, Journal of Finance, 45, pp. 959–976

HAMILTON, J D (1983) “Oil and the macro-economy since World War II”, Journal of Political Economy, 91, pp 228–248

HAMILTON, J. D (1985): “Historical causes of postwar oil shocks and recessions”, Energy Journal, 6, pp 97–116

HAMILTON, J D (1988a). “A neoclassical model of unemployment and the business cycle”, Journal of Political Economy, 96, pp 593–617

HAMILTON, J D (1988b) “Are the macroeconomic effects of oil-price changes symmetric ? A comment”, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Senes on Public Policy, 28, pp 369–378

HAMILTON, J D. (2003) “What is an oil shock?”, Journal of Econometrics, 113, pp 363–398

HOOKER, M. A. (1996) “What happened to the oil price-macroeconomy relationship?”, Journal of Monetary Economics, 38, pp 195–213

MORK, K A (1989). “Oil and the macroeconomy when prices go up and down An extension of Hamilton’s results”, Journal of Political Economy, 91, pp. 740–744.

ROUTLEDGE, B R. and D. J. SEPPI (2000): “Equilibrium forward curves for commodities”, Journal of Finance, 55, pp. 1297–1339.

SCHWARTZ, E S (1997): “The stochastic behavior of commodity prices Implications for valuation and hedging”, Journal of Finance, 52, pp 922–974

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Additional information

We would like to thank Manuel Ammann, Bernd Brommundt, Stephan Kessler, Ralf Seiz, Michael Verhofen, Hemrich von Wyss, and two anonymous referees for helpful comments We are particularly indebted to Sergej Peisotchenko at United Energy System (UES) of Russia and Jan Gjerde at Shell for clearing us up on technical aspects of oil production

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Brevik, F., Kind, A. What is going on in the oil market?. Fin Mkts Portfolio Mgmt 18, 442–457 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11408-004-0407-3

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11408-004-0407-3