Abstract

Can village leaders’ performance impact villagers’ trust in the central government? Using village leader-villager relations at the village level as the explanatory variable, we examine a previously ignored source of public trust toward the Chinese government: face-to-face interactions with local leaders. We argue that, as the party-state’s first point of contact with villagers, villagers use their interactions with village leaders as a proxy to determine the trustworthiness of China’s central government. By analyzing the latest Guangdong Thousand Village Survey from 2020, we find that when villagers report better relations with village leaders, they also express greater trust in the Chinese central government. We find additional evidence for this relationship through open-ended interviews of villagers and village leaders. These findings advance our understanding of hierarchical political trust in China.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite policy challenges and missteps, the Chinese government under the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seems to enjoy notably high levels of public approval, significantly higher than many similar regimes (Mitter & Johnson, 2021; Cunningham et al., 2020). Moreover, Chinese citizens tend to express higher levels of trust in the central government than in local governments (Li, 2004; Li, 2013). The received wisdom claims that most people perceive the center as benevolent, while blaming local leaders for poor implementation of Beijing’s right-minded policies, in a phenomenon described as “hierarchical trust” (Li 2016).

Although existing research on political trust in China has disaggregated trust in various levels of government, scholars have not yet explored how face-to-face interactions with grassroots leaders, such as village leaders, may impact trust in higher levels of government. This paper sheds light on a previously neglected source of trust in China’s central government: the ability of village leaders to build relations with villagers. By examining survey data on village leaders’ implementation of pandemic mitigation policies from 2020, we show that the relationship between villagers and village leaders is positively associated with trust in the central government.

By focusing on whether the relationship between villagers and village leaders is associated with trust in the central government, we test whether there is evidence to suggest that villagers use their interactions with local leaders as a proxy to judge the overall performance of the regime, including the central government. A null finding between leader-villager relations and trust in the central government would suggest that villagers tend to disaggregate the levels of government when evaluating their performance. Our analysis suggests that, despite the phenomenon of hierarchical trust, local leader performance can impact trust in the central government. Thus, our findings imply that scapegoating local leaders for policy failures may not always be a successful strategy to bolster support in the regime.

In our analysis, we use data from the 2020 Guangdong Thousand Village Survey (GTVS), which asks villagers to rate their relations with village leaders as well as their perceptions of central leaders’ pandemic mitigation policies. COVID-19 provides an appropriate context to examine whether local leader performance is associated with central government satisfaction, as the virus has indiscriminately subjected governments and authorities across the globe to a pressure test of emergency responsiveness. Furthermore, COVID-19 mitigation was top-of-mind for citizens in China in 2020. Finally, COVID-19 mitigation policies are widely understood as designed by the central government with relatively little discretion afforded to local leaders.

Despite serious errors of judgment by local officials in Wuhan who were slow to recognize the severity of the virus, once the central government mobilized a clear response, the CCP’s campaign-style “zero-COVID” policy, and subsequently “dynamic zero-COVID”, kept cases and deaths relatively low throughout 2020 and 2021. In 2020, when the GTVS was conducted, several scholars found that the Chinese people were generally pleased with the party-state’s approach to the pandemic, likely due to the comparatively low numbers of COVID cases and deaths in China (H. Huang et al., 2022; Su et al., 2021; Wei et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2021). Although some observers expressed concerns about the draconian implementation of strict lockdowns, widespread testing, and surveillance, these mitigation measures allowed many Chinese to engage in activities that were restricted in other countries at that time, ranging from sending their children to in-person school to going to the movie theatre. Thus, while the early stage of the pandemic confounded many other governments, it may have served to reinforce support in China’s party-state in 2020.

This research furthers our understanding of political trust in China. Scholars contend that trust in government is important to maintain regime stability (Easton 1975), especially in an authoritarian party-state such as China, which does not rely on a democratic process to select leaders. This study suggests a new pathway for the party-state to cultivate grassroots political support for the regime in the context of campaign-style policy implementation: face-to-face relations with local leaders (Easton 1975). This research underscores the importance of policy implementation for regime support and suggests strategies to improve good governance by improving leader-villager relations.

To preview the findings, we argue that villagers’ perceptions of their relations with village leaders are positively associated with villagers’ expressed trust in the central government. Although they are not formally considered government officials, village leaders are the first point of contact with the party-state for most villagers. Villagers’ repeated interactions with village leaders can either develop mutual trust or animosity. Personal relationships (or guanxi 关系) matter significantly in people’s daily lives in China, ranging from getting a child into a prestigious primary school to operationalizing business transactions to winning a grant from the government (Bian 2019, pp. 169). We contend, therefore, that relations between villagers and village leaders also affect how villagers see the central government and the party-state. Mutual trust developed through cordial and constructive interpersonal relations at the local level breeds, protects, and ultimately reinforces popular support of the CCP and the government.

This article proceeds as follows. First, in the literature review, we explain how our study contributes to the field by speaking to the political trust literature. Second, we discuss the current role of village leaders and propose our hypothesis regarding the relationship between villager-village leader relations and trust in government. We also explain the causal logic for a relationship between local leader-villager interactions and villagers’ political trust in the central government. Third, we discuss the research design and findings from fieldwork. We then detail the source of the data, variables, and statistical models. This section is followed by our statistical analysis and robustness checks. Lastly, we conclude the paper with a discussion of our findings and broader implications.

Political Trust in China

The scholarly research on popular trust toward the Chinese government focuses on three major lines of inquiry. First, the Chinese government, in general, enjoys a notably high level of popular trust, particularly when compared with authoritarian countries, even when accounting for nonresponse, refusals, and social desirability bias (Hu, 2021; Hu & Yin, 2022). Second, political trust is disproportionately distributed across different levels of government. Chinese tend to express more trust toward the central government, while blaming local authorities for policy blunders. This pattern of greater trust in higher levels of government has been described as “hierarchical trust.” The central government may, at times, exploit this pattern by scapegoating local officials when policy disasters occur. Third, scholarly research examines the sources of political trust, including which policy outcomes are associated with greater trust in government. This section will focus on the second and third lines of inquiry, as a basis to derive a hypothesis for this study.

Hierarchical trust, coined by Lianjiang Li, refers to the phenomenon whereby many Chinese tend to express more trust in central authorities as compared to local authorities. Across various surveys, between one-third and almost two-thirds of respondents expressed hierarchical trust (Li 2016). Moreover, Li (2016) finds that satisfaction with political democracy, satisfaction with government policies, and trust in provincial and county government leaders are all positively associated with trust in the central government.

In China, the central government assigns different priorities to the central and local governments. Whereas the central government is primarily preoccupied with macro-level strategies and broad goals, local governments are confronted with the practical issues of policy implementation. While allowing a certain degree of autonomy to local authorities, the central government still holds veto power to intervene and investigate local issues in times of need. Moreover, Xi Jinping has reduced local leaders’ discretion, as compared to his predecessor. As grassroots leaders are in the most direct contact with society, they are often responsible for implementing objectives prescribed by the central government, such as enforcing COVID mitigation measures.

Controversial policies, such as land confiscation from individual households, present local governments with imminent administrative challenges which may contaminate their public image. For example, Zhao and Xie find that farmers who experienced land expropriation expressed lower trust in local cadres, due to both lower perceptions of quality of life and greater conflicts with local cadres (Zhao and Xie 2022). Thus, local governments have accumulated most, if not all, of the complaints and criticisms from Chinese society, while the central government, which is rarely directly involved with social conflicts, reaps praise and public recognition. Thus, this structural feature of the Chinese political system keeps the central government at a distance from the grassroots, which then helps dissociate the center from immediate political backlash to unpopular policies. It instead frames the center as a benevolent authority.

Research on the sources of political trust in China have found that government performance matters for trust in government and social policy provision can increase trust in government. Han and his co-authors find that perceptions of “quality of governance” are associated with trust in government at all levels (Han et al. 2019). Dan Chen finds that government performance is associated with trust in the central and local governments across policies issues including the economy, corruption, and public service provision (Chen 2017). Other studies link policies to political trust across a range of issues including air pollution (Flatø 2022), poverty alleviation (Zuo et al. 2021), anticorruption campaigns (Kang and Zhu 2021), hukou (residence permit) reforms (Huang 2020), pensions (Li and Wu 2018), non-government organizations (Farid & Song, 2020; Song 2022), and healthcare (Duckett and Munro 2022).

While some argue that hierarchical trust stems from the structural setup of the political system in China (Cai, 2008; F. Chen, 2003; X. Chen, 2009; Tong & Lei, 2010), others contend that it is a phenomenon that has been intentionally manufactured by the Chinese regime (Su et al. 2016; Wu and Wilkes 2018). Employing the Asian Barometer Survey data, Wu and Wilkes find that political fear and exposure to political news are positively associated with hierarchical trust, suggesting that the Chinese political system contributes to the phenomenon of hierarchical political trust (Wu & Wilkes, 2018, p. 447). In addition, they find that political satisfaction is negatively associated with hierarchical trust, thereby suggesting that those who are less satisfied with policy outcomes are more likely to express hierarchical trust (Wu & Wilkes, 2018, p. 447). Our research extends this finding as our data indicate that good relationships with village leaders may have positive feedback effects for trust in the central government.

Zhenhua Su and his co-authors contend that hierarchical trust is a result of strategic orchestration by the Chinese party-state. They find that propaganda is the main predictor of hierarchical trust, whereas economic development and traditional values do not seem to be associated with hierarchical trust. Thus, Su and his co-authors conclude that hierarchical trust is likely a phenomenon that is manufactured, or at least encouraged, by the central government through political propaganda and intentionally scapegoating local officials in response to policy failures (Su et al. 2016). This type of “internal scapegoating” allows social discontent to accumulate against part of the system (local officials), while preserving the ruling stability of the whole. In this account, internal scapegoating is rather intentionally initiated by the Chinese government to sacrifice local leaders, but protect the legitimacy of the central government and the system overall.

Li’s (2016) pathbreaking research suggests that policy outcomes and perceptions of local officials may impact trust in the central government. Based on these findings, Li posits that (dis)trust in local officials may reflect (dis)trust in the center, which may indicate lower trust in the central government than scholars have previously suspected. Li argues that, when respondents express distrust in the local government, they are conveying skepticism in the center’s capacity to enforce its preferred policies. In a similar vein, Chen’s research suggests that scapegoating local officials may not be effective for regime legitimacy as distrust in local officials is associated with reduced support for the regime overall (Chen 2017). Therefore, lack of trust in local government can signify concerns about the political system overall.

Due to the hierarchical nature of China’s Leninist-style party-state, local leaders are held accountable by the next level up from them in a series of nested, dyadic relationships that culminates in the central leadership. Thus, the center could, theoretically, ultimately be held responsible for the behavior of local-level leaders, especially in the context of a high-priority, highly publicized policy with clear central direction, such as China’s so-called “zero-COVID” approach to the epidemic (Zhang et al. 2021). Following Li’s research, trust in local leaders may indicate how respondents evaluate the center’s “commitment and capacity” to implement policies (Li 2016). We build on Li’s findings by exploring to what extent villagers’ relationships with village leaders may be associated villagers’ trust in the center. In our study, since COVID-19 response was at the forefront of many people’s minds, one may reasonably expect that trust in local government may reflect an evaluation of whether the center is committed and able to enforce measures to contain the epidemic. For instance, in their study of citizen satisfaction of government performance during COVID-19, Cary Wu and his co-authors show that Chinese approval of government performance in preventing the spread of the novel coronavirus increases as the level of government being evaluated increases (Wu et al. 2021). Su and co-authors find that government performance, along with prior expectations and generalized societal trust, are associated with trust in government during the early stages of the pandemic (Su et al. 2021).

Conventional wisdom assumes that local leaders’ malfeasance does not necessarily undermine trust in the central government because the center can scapegoat local officials amid a narrative of the benevolent center, although Lianjiang Li and Dan Chen challenge this assumption (D. Chen, 2017; L. Li, 2022). However, as will be discussed in the following section on village leaders, Xi Jinping has actively re-centralized power, instituted sweeping anti-corruption party discipline, and extended the reach of the CCP further into the grassroots in both rural and urban settings through village committees and the grid system, respectively. These shifts imply that local leaders’ actions should be in line with central directives, especially in the context of a national emergency such as the pandemic, thereby undermining the narrative of “a benevolent center, but inept local leaders.”

Unlike previous research, we extend the analysis to the lowest level of leaders in rural areas: village leaders. As will be discussed in the next section, although they do not enjoy the same benefits as other government employees, village leaders are increasingly pressured to follow directives from higher levels of the party-state, rather than the popular will of the villagers. Whereas previously village leaders received minimal funding from the state, now village leaders are on the same payroll as formal government officials. Therefore, we hypothesize that villagers may use village leaders as a proxy to evaluate the performance of the center.

Village Leaders to the Party-State: from Liaison to Agent?

Village leaders in China theoretically serve as a liaison between the government and the villagers. Village leaders are not officially incorporated into the state system (tizhi 体制) and therefore do not enjoy the same level of job security as official civil servants, as the official state system comprises government employees from the central to the township level.Footnote 1 Nonetheless, village leaders are under the unquestionable authority of higher levels of government. Village leaders are responsible for communicating and implementing policies that are adopted at higher levels of government as well as managing day-to-day affairs in the village. They are responsible for reading out government announcements (zhengfu gonggao 政府公告)Footnote 2 and communicating the official intent behind government policies to villagers. Village leaders also make decisions regarding the distribution of public goods and mediate conflicts between villagers. China’s party-state also relies on village leaders to convey village public opinion to higher levels of government, so that the government can respond appropriately to serious grievances.

Village leaders are the main channel for villagers to interact with the government for daily affairs. Face-to-face interactions are crucial for villagers, as many villagers are elderly or left-behind children. Villages in China are often characterized as “hollowed out” (kongxinhua 空心化), because working-age villagers tend to migrate to cities for better employment opportunities. As a result, the remaining village population tends to be elderly. The average age of respondents in the GTVS data used in this study is about 58 (see Table 1). Although villagers in theory can appeal to higher levels of government for particular grievances, this approach is costly, unlikely to be successful, and could result in retaliation from village leaders (Li 2013). As a result, the village government is the most immediate channel for villagers who aspire to interact with the Chinese government (Table 2).

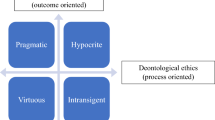

As a key liaison between villagers and the hierarchical party-state and the most immediate mouthpiece of the Chinese government (Ye & Cai, 2021), village leaders could shape the relationship between villagers and the Chinese party-state in favor of the government, in favor of the villagers, or in balance of both parties. In practice, however, village leaders mainly serve as compliant subordinates of the party-state apparatus to execute government policies, especially in the Xi Jinping era.Footnote 3 Village leaders are unlikely to undermine the Chinese government to sympathize with discontented villagers and even less likely to stray from the interests of the Chinese government to draw distraught villagers into personal alliance with themselves. Instead, village leaders are incentivized to frame government policies in ways both favorable to the government and understandable to the villagers (Xu & Zeng, 2002).

Although village leaders are ostensibly elected by villagers, they tend to act as representatives of the party-state, rather than advocate for villagers. This is the case for several reasons. First, the CCP has intensified control over village leadership through the policy of “one shoulder pole” (yijiantiao 一肩挑), which could also be expressed as overlapping directorates, as of 2019. The village committee changed from the previous dual-leadership, where one person serves as the party secretary and another serves as the democratically-elected village leader, to the unified leadership where the party secretary and village leader are the same person. This institutional reform determines that the village leadership primarily identifies itself as a local party cell of the CCP whose chief mandate is to embed the will of the CCP among the grassroots networks (Wang and Mou 2021).Footnote 4 As of 2020, when the data were collected for this study, further CCP consolidation over village committees was underway. Second, village leaders do not have the resources to defy the CCP. The township government manages the village’s coffers, the appointment of leadership personnel,Footnote 5 and other administrative resources, making village leaders dependent on higher government authorities. Village leaders now have very limited room to oppose higher levels of government.

In addition to the fact that the institutional set-up deprives village leaders of the administrative authority to control the village budget, village leaders also have personal incentives to curry favor from higher government officials, which makes aligning with higher authorities a rationally favorable option. Wei and Wang (2021) find that candidates seek the position of village leader to establish for themselves a name in the political realm which affords political resources that might benefit their family members who are doing business in the same locality (pp. 114). This observation is also confirmed by the first author’s field research. Some village leaders with exceptional performance in village governance, though rare, can actually “break” into the official state system (Wei and Wang, 2021: 115). In the first author’s fieldwork, one of the village leaders was formally admitted into the official civil servant system partly due to her exceptional governance skills as a village leader. This village leader was particularly good at building personal relationships with fellow villagers, which further helped mobilize the villagers to implement local programs. By getting villagers to work together, the village leader gained recognition from higher authorities, who then recommended her for the prestigious, official civil service exam. She passed the exam and became the rare, one in more than a hundred, “breakthrough” in the entire county.Footnote 6

In the context of greater recentralization and party discipline down to the grassroots, we speculate that villagers are likely to use their face-to-face relations with village leaders as a proxy to evaluate the central government. Thus, we posit our hypothesis:

Hypothesis

As village leader-villager relations improve, villagers’ trust in the central government increases as well.

Fieldwork and Semi-Structured Interviews

The first author conducted the fieldwork portion of this research. In addition to periodic field trips from 2017 to 2020 to various localities in mainland China, he conducted semi-structured interviews in Shanxi Province and Henan Province in December 2021 and in Jiangsu Province in February 2022.

In Shanxi Province, he interviewed a group of about twenty village leaders in the county party school where they had come for regular training. In addition to the group interviews, he also interviewed one county-level government official and one township party secretary. In Henan Province, the first author visited three villages and interviewed the village leaders. In addition, the first author interviewed two county-level government officials, both of whom have worked at the grassroots for more than ten years. In a separate field trip to Jiangsu Province, the first author visited one township government and two local villages, interacting with county-level government officials, township government officials, and village leaders.

Besides the field interviews, the first author also conducted remote interviews via Wechat. He conducted follow-ups with local officials via Wechat after the field trip. The evidence he collected in this part of the fieldwork mostly contributed to the theoretical framework of this paper.

Conversations with village leaders at the party school in Shanxi Province revealed frequent complaints from village leaders about how villagers do not trust them. Several village leaders grumbled about how hard it is to deal with the villagers. Although some of the grumbling comes from a particular case with a particular villager, the first author’s field observation was that the lack of mutual trust between village leaders and villagers is widespread and serious.

In addition, the first author, along with Cantonese translators, went to six different villages located in four different municipalities in Guangdong Province and conducted in-depth personal interviews with 31 villagers, two village leaders, and five county-level government officials. These six villages are among the 119 villages sampled in the GTVS. In total, 40 individuals participated in the first author’s field interviews (see Interview Table 3).

Findings from Semi-Structured Interviews

Field interviews with villagers, village leaders and county-level government officials in Guangdong Province support the hypothesis. Almost all of the villagers interviewed expressed unwavering trust in the central Chinese government. Most of the interviewed villagers showed more trust toward the central government than the local government. Hierarchical trust is evident as respondents indicated explicitly contrasting opinions of the central and local governments. When asked whether they trust the central and local governments, the most frequently heard response from the villagers is, “the intent of the central government is good, but the local implementation is not,” which is consistent with the conventional wisdom regarding hierarchical trust.

The first author’s field interviews in Guangdong also found support for the hypothesis that personal relations with the village leaders affect their trust in the central government. Robust personal relations with village leaders make a noticeable difference in the degree to which villagers trust in the central government. Villagers closely associated with the village leaders have developed political trust toward the central government through comprehensive studying of, or repeated interactions with, village leaders, whereas those distant from village leaders only retain a general, good impression of the central government that does not stem from solid fact-finding or sustained engagement with the government.

According to these interviews, there is a noticeable difference between those who are close to the village leaders and those who are not. Those who are close to the village leaders trust the central government with more enthusiasm and assuredness when answering the interview questions. This type of villager could usually, without much hesitation, cite relevant policies, such the poverty relief program, to substantiate their answers. For example, three of such villagers replied with confidence that the central government is very good because of the subsidies it made available to rural farmers. They all noticed the significant change in infrastructure in rural China, such as paved concrete roads, wireless Internet connections, and online retailing, which serve as evidence of the central government helping the Chinese people, from their perspective.Footnote 7

By contrast, most interviewees did not identify any close relationship with village leaders. While villagers who lacked a close relationship with village leaders also reported that the central government is trustworthy, their opinion appeared to be more elusive. When probed regarding the reason why they trust the central government, villagers who were distant from village leaders showed little concrete understanding of how the central government has (or has not) served the interests of the people. This group of interviewees appeared less prepared and even a bit surprised when asked their opinion about the central government. They often had to pause and think before making up their opinion. One of these villagers even told the first author that he did not really know anything about the central government.

The question about trust toward the central government seemed a less relevant concept for villagers without close relations with village leaders. When asked about his opinions of the central government, one villager instead began explaining the difficulties that the village faces, including pressing issues such as unemployment during COVID-19. Before long, a group of his fellow villagers gathered around the interview site and started discussing the problems they faced. When asked about the central government, villagers immediately jumped to practical grievances that awaited government actions.Footnote 8 Trust toward the central government, as observed in this fieldwork, is an elusive concept tantamount to a slogan of “political correctness,” which often amounts to nothing concrete or beneficial for villagers’ daily lives. None of these villagers had good relations with village leaders.

Lack of a good personal relationship with the village leader leads to increasing political disenchantment. Such villagers are more likely than others to articulate their disappointment with the village leadership. Such disappointment may impact opinions of higher levels of government. For example, another villager in a separate village replied to the question regarding trust in the central government, “even appealing to the center does not change much.” In a very rare and extreme case, another villager developed a rather negative perspective of the central government because of unpleasant encounters with the village leadership in the past.

However, there are exceptions to the above observations, for there are increasingly alternative routes to get around the village leaders to form an opinion of the central government. Some interviewees did not have close relations to the village leaders but at the same time remained very confident in the central Chinese government. They are generally those who are able to form independent opinions of the country. For example, a woman in her fifties was very outspoken about her dissatisfaction with the village leadership as well as the local government. She was surprisingly very certain about the benevolence of the central Chinese government, referencing how the central government does good things for the people. When asked where she accessed information about the central government, she said that, as three of her children were all in college, she had joined the mothers’ Wechat group of her kids.Footnote 9 These Wechat groups are arenas where up-to-date exchanges of information occur. As villagers in China increasingly have better access to the Internet and new media platforms, such as Wechat and Douyin, China’s Tiktok, village leaders’ role as liaisons is likely to become less essential.

Survey Data

The Guangdong Thousand-Village Survey (GTVS) is a time-series survey collected each year by the Economic and Social Research Institute based in Jinan University. We use the 2020 wave, which was conducted in July when the COVID-19 pandemic was largely under control in China and interviewers were allowed to travel to local villages for data collection. The survey randomly selects, through Probability Proportional to Size Sampling (PPS), 30 households from each 119 administrative villages across Guangdong Province, China.

The project adopts the Computer Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) approach to collect data. The researchers recruited and trained 235 students from Jinan University before deploying them to the field. The mobile computer tablets provided by the CAPI program equipped the interviewers with the essential technical convenience to record data collected in the field immediately onto the online platform based at Jinan University.

The GTVS collects data as rigorously as possible. The target population is rural villages and villagers across Guangdong Province. The data are collected both at the village level and at the household level. The 119 villages are randomly selected via computer randomization tools. Within each selected village, the survey uses computer software to randomly select households on Google Maps. With the households identified, interview teams were dispatched to the villages and the village committee members assisted the interviewers in contacting the selected households. Rigid quality control methods are in place. The interview processes are all voice-recorded and the data information live-transmitted back to the data center. Live question-and-answer lines from the survey center to the field interviews are open throughout the data collection processes. Interviewers may reach out to the survey center should any confusion arise. The survey assigns professionally trained administrators to double-check the recordings to make sure that the results are correct. In addition, quality inspectors are also deployed to the interview sites to make sure that the interviews are conducted properly. Given the various dialects in Guangdong, the survey selects university students who are from nearby areas of the selected villages to collect the data. While we also employ data at the village level for robustness checks, the level of analysis for this study is each household. Our analysis includes 3126 observations from 119 villages (see Model in Table 4). Although there are missing values, we do not find selection bias that would compromise our conclusions.

Survey research in China continues to grapple with the issue of nonresponse and preference falsification. Neil Munro finds that unit nonresponse, also known as refusal bias, may have contributed to overestimates of trust in government by as much as 6% (Munro 2018). Furthermore, item nonresponse and preference falsification present a serious concern when enumerators ask respondents about China’s central government, leading to artificially high estimates of trust in the center as compared to trust in local government (Ratigan & Rabin, 2020; Shen & Truex, 2021). However, if respondents’ expressed distrust in local government reflects latent distrust in the center, as Lianjiang Li argues, scholars may be able to utilize expressed hierarchical trust to reveal a more accurate estimate of the “true” level of trust in government. In the GTVS data, respondents seemed to be straightforward with their opinions. We therefore believe that the current data work well for our study. Nonetheless, even accounting for nonresponse, we find an association between village leader-villager relations and trust in the central government.

Variables

The dependent variable in this study is Trust in center, trust toward the central Chinese government concerning controlling COVID-19. Respondents are asked to rate the degree to which they agree with the statement that “in terms of controlling COVID-19, the Chinese central government is trustworthy” from 1 to 5, with 5 being “strongly agree” and 1 being “strongly disagree”.

The independent variable is Leader-villager Relations (villager), which captures respondents’ perception of their relationship with their village leaders. Respondents are asked to rate their relationship with their village leaders from 1 to 5, with the value of 5 being the best and the value of 1 being the worst.

In addition to the dependent variable and the independent variable, we also include a number of control variables to take into account other factors that might be associated with the dependent variable. First, we control for the different COVID-19 measures taken by individual villages. Though localities across China tend to follow strictly the pandemic-control mandates issued by the central government, there is some degree of variation in the actual implementation process. For instance, while some villages completely locked down in Guangdong in 2020, others did not. So, we include in our study the control variable “COVID Lockdown” to account for whether a village completely shut down in 2020. The rigor of measures taken to prevent COVID-19 might have an impact on how villagers in that village see the central government.

Likewise, we also include the control variable “COVID Goods,” which captures whether a given village distributed COVID-related goods, such as masks and hand sanitizer. This control variable is included because villagers who had access to free pandemic goods might develop a better impression of the government as a whole.

In addition to the COVID prevention measures taken by the village, we also control for the kind of support that villagers have received from the Chinese government during the pandemic. The four controls are Funding, Sales boost, Loans, and Training, which capture four different types of government support granted to villagers during the pandemic. The first kind, Funding, codes information on whether respondents have received government support in the form of cash. The variable Sales boost records whether respondents have received government help to boost sales of their agricultural products. The variable Loans captures whether respondents have received government loans for economic activities, while Training accounts for whether respondents have received government support for career training and skill building.

In addition to individual characteristics of respondents, such as Age, Education, Gender, Marital status, Income, Land ownership, Household size, Ethnic minority, Village leader, Residence and Party member, we also include Leader violation, respondents’ general assessment of the frequency of village leaders violating villagers’ interests. This control is included because village leaders’ violation of villagers’ interests may damage villagers’ perception of the Chinese government and therefore could affect how much they trust the Chinese government in the case of an emergency like the pandemic. Table 1 offers the descriptive statistics of all the variables included in our regression analysis.

Descriptive Analysis

As seen in Table 2, among all the respondents, 79.43% “strongly” agree with the statement that the Chinese government is trustworthy in the matter of COVID-19 prevention, 16.63% choose to agree with the same statement, while only 4% choose to stay neutral and 0.74% choose to disagree with the statement.

In terms of villagers’ perceptions of their relationship with the village leaders, 18% of respondents report that their relationship is very good, 23.35% report that their relationship is relatively good, while a great portion of 46% of the respondents remain neutral and 19% think that their relationship is poor.

The pandemic has caused stress to some villagers’ lives. 21% of respondents report that the pandemic has negatively affected their work. During the pandemic, the most significant challenge that villagers face is limited cash flow. Among all setbacks, 24.3% of respondents report such difficulty, the highest percentage. Challenges include difficulties selling agricultural products and the rising costs of raw materials.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analyses lend support to our hypothesis. Given that our dependent variable is an ordinal variable, we choose to employ an Ordinal Logit model (Model 2 in Table 4) for our analysis. Table 4 shows two statistical models. From left to right, we started with a simpler model with fewer controls, and then add more control variables to verify the validity of our models. Doing so is beneficial in that gradually including more control variables demonstrates how with/without certain control variables the validity of the models changes. In addition, as more control variables are included and the number of observations of different models changes, we are able to observe how missing values affect the relationship between the independent and dependent variables.

The independent variable, Leader-villager Relations (villager), has uniformly achieved strong statistical significance across models at the 1% level, lending convincing evidence to suggest that how village leaders get along with villagers is positively associated with how villagers perceive the central government. The statistical significance remains strong even after incorporating all controls, including both individual and village-level controls, indicating that the strong association between the dependent variable and the independent variable survives various model specifications.

In Model 2, the independent variable has a statistically significant, positive association with the dependent variable, at the 1% level, implying the null hypothesis that the independent variable has no impact on the dependent variable can be rejected. As the dependent variable is ordinal, the marginal effect of the independent variable cannot be intuitively obtained by interpreting the coefficient. We instead use the margins command in Stata to obtain the substantive impact of the independent variable. As seen in Fig. 1, with all other variables held at their mean value, when Leader-villager Relations (villager) increases from the value of 1 to the value of 5, the probability of Trust in center obtaining the value of 5 relative to other options increases from 67.7 to 91.2%. This suggests that, as a villager’s relationship with their village leaders improves from the worst to the best, the probability that they strongly agree with the statement that “the central government is trustworthy in terms of COVID-19 prevention” increases by 35%. This increase is statistically significant across all the models and survives multiple robustness checks.

This analysis lends strong evidence to our hypothesis that the relationship between the village leadership and the villagers is associated with how villagers perceive the central government. Better and improved relationships between the village leadership and villagers help villagers develop positive perceptions of the central government and the villagers are more likely to trust the central government in the emergency case of a pandemic.

We include in our multi-level models (Model 3 in Table 5), clustering at the village level, the same independent variable but evaluated from the perspectives of the village leaders, Leader-villager Relations (villager). While villagers are asked in the survey what they think of their relationships with village leaders, village leaders are also asked the same question, only in terms of the relationship between the village leadership and villagers in the entire village. We cluster the models at the village level.

After incorporating Leader-villager Relations (villager) in our model (Model 3 in Table 5), the findings confirm our above finding. As seen in the last model in Table 5, the independent variable Leader-villager Relations (villager) has a statistically significant (p < 0.01), positive association with villagers’ trust toward the central government.

What is surprising but also interesting is that village leaders’ assessment of their relationship with villagers has no association with the dependent variable. As Leader-villager Relations (villager) increases from the lowest value of 1 to the highest of 5, we find that the probability that villagers in this village “strongly agree” with the statement that the central government is trustworthy in terms of pandemic control does not show noticeable change. Village leaders’ evaluation of their relationship with villagers has little to no apparent effect on how villagers see the central government.

The control variables regarding COVID-19 relief and mitigation efforts merit discussion. Several pandemic-related policies were not associated with trust in the central government, including village lockdowns. However, two of these policies were positively associated with trust in the central government: government help to boost agricultural sales and government support for career training and skill building. Although this study focuses on local leader-villager relations, these control variables suggest that further research could examine the relationship between various pandemic policies and trust in different levels of government.

Robustness Check

First, we employ an OLS model as a baseline check of the robustness of the model. The results show that villagers’ perception of village leaders have a statistically significant impact on how they see the central government.

Second, multilevel modelling using the cluster function to “condense” the unit of analysis to the village level is a useful approach to take into account systematic village-level factors that could affect the dependent variable. The clustering model (Model 3 in Table 5) yields similar results as our main finding.

Third, to control for potential bias caused by omitted variables, we have included in our models important control variables at both the household and village level, such as Education and Locations of villages. For instance, villages closer to the township seat are more likely to be economically developed and more connected with the outside world. Their villagers may hold different views toward village leaders and the central government. Including these controls, however, does not significantly affect the statistical significance of the independent variable.

Fourth, in order to control for potential sampling bias, we conducted a robustness check, not including control variables with large numbers of missing values (except Leader-villager Relations (villager) and Trust in center, which are the dependent variable and core independent variable), we find that the significant relationship between Leader-villager Relations (villager) and Trust in center, shown in Model 1 of Table 4, does not change. The variable with the most missing values is land, which has valid numeric values in only half of the sample, in 1819 observations. This variable asks respondents how many acres of accredited land a villager has. Respondents failed to provide the information mainly because their land was not yet accredited by the state. The accrediting process started in recent years but took a couple years to finish. When the data were collected, the process was still ongoing in part of Guangdong Province. In addition, a few other variables record many missing values: Property, Income, the core independent variable Leader-villager Relations (villager), the dependent variable Trust in center. The total number of observations with missing values in one or more of these four variables are 993. Our model exercise without these variavillagers express trustbles shows that our findings remain valid.

In addition, we also performed stochastic multiple imputation with multivariate normal distribution (MVN) to address potential bias introduced by the missing values (see Model 4 in Table 5). Model 4 imputes the missing values and thus retains 3139 observations from 118 villages. The exercise continues to support the current findings.

Fifth, reverse causation, or endogeneity, would warrant our concern if villagers had sufficient contact with the central government that they could form their own opinions of the central government independently from the village leaders and such that their interactions with the center also affected their perceptions of the village leaders. However, the reality is that villagers must interact with village leaders before understanding the central government. The likelihood that villagers’ perception of the central government impacts their trust in the village leadership remains low. There is a possibility that, in the context of hierarchical trust, villagers who trust the central government tend to develop positive or negative feelings about the village leadership, even when they have no solid evidence for such feelings. Following the received wisdom regarding the central government scapegoating the local government, the effect, if any, should be that villagers’ knowledge of the central government negatively impacts their perception of village leadership. A positive association between the independent and dependent variables, as identified in this paper, suggests that endogeneity is not likely to impact the findings. Endogeneity would indeed be a significant concern when future studies focus on younger and more urban respondents, who use different sources of information in forming their opinions about the government.

Conclusion

In this study, we argue that villagers’ evaluations of their relationship to village leaders are positively associated with their trust in the Chinese central government. Due to the elderly population and the relatively isolated circumstances in rural China, villagers are less likely to bypass village leaders to form an independent opinion of the central government. However, rapid urbanization and technological development will likely reduce the importance of face-to-face interactions with village leaders.

We subjected the theoretical argument to a mixed methods approach, with both in-depth field interviews and empirical survey data analysis. In-depth interviews reveal that, while most villagers express trust in the central government, personal relationships with village leaders impact how and why they hold trust in the center. Villagers are more likely to express well-substantiated trust in the central government if they have close personal relationships with village leaders. In interviews, villagers with good relationships with village leaders expressed trust toward the central government with certainty, confidence, and concrete examples of what the government has done for villagers. By contrast, villagers without these close relationships may still verbalize trust in the central government, but they communicate their trust as a general impression. When further prodded about how and why they trust the central government, these villagers hesitate and struggle to offer persuasive evidence, suggesting that they may be parroting a “politically correct” answer. The statistical analysis confirms the findings of our field interviews, leading us to conclude that village leader-villager relations play a key role in shaping villagers’ trust in the central government. The better villagers’ relationship with their village leaders, the more likely that villagers strongly trust the central government.

This study has several limitations. First, most surveyed villagers are of the elderly, left-behind generation. Younger generations are more likely to use technology to access information and interact with the government, thereby shaping their perceptions of the party-state. Second, survey questions about political trust are entirely subjective. For instance, about two-thirds of the survey sample have villagers and village leaders disagreeing about the quality of their relationship. These different views introduce methodological challenges. We find that many village leaders tend to over-report the quality of their relationship with villagers, which is unsurprising. Villagers’ assessments can be inaccurate as well. Villagers may report difficulties in their relations with village leaders because there are latent tensions between the village leaders and villagers. Meanwhile, village leaders may be unaware of these tensions or intentionally presenting their relationships with villagers as harmonious, regardless of reality. These tensions, when not channelled via good communications in a timely fashion, may surface in our survey as popular discontent. Future research can further examine the possible motives of both village leaders and villagers in exaggerating their relationships.

In fieldwork, conversations with village leaders at the party school in Shanxi Province revealed quite frequent complaints from village leaders about how villagers do not trust them. Several village leaders grumbled about how hard it is to deal with the villagers. Although some of the grumbling comes from one case with one specific villager, the first author’s field observation was that the lack of mutual trust between village leaders and villagers is widespread and serious.

Additional field interviews with government officials and on-site visits to eight villages further confirm our estimate of the current state of village leader-villager relations. Most village leaders serve as passive Subordinate Executive Officers (SEOs) of government policies. Their chief goal is to respond to calls of higher levels of government while maintaining village stability. While some village leaders engage villagers in entrepreneurial economic activities that enrich the village’s collective coffers, most village leaders struggle terribly in allocating limited personal energy and attention between their own family business and the collective well-being of the village. To revitalize the Chinese countryside, village leaders and villagers will need to engage with each other in mutual trust and improvise novel strategies to cultivate development.

Future research should delve into strategies that can help rebuild trust between village leaders and villagers. Both bottom-up experiments to mobilize villagers into the collective decision making of village affairs and top-down government-mandated village reconstruction programs may have the potential to build community at the village level and foster the future development of China’s villages.

Notes

Interview 1; Interview 10.

Interview 2; Interview 11.

Interview 3; Interview 10.

Interview 4; Interview 11.

Candidates of village elections must be party members according to the 2019 reform.

Interview 5.

Interview 12.

Interview 13.

Interview 14.

References

Bian, Yanjie. 2019. Guanxi, how China works. John Wiley & Sons.

Cai, Y. 2008. Power structure and Regime Resilience: contentious politics in China. British Journal of Political Science, 38(3). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123408000215.

Chen, D. 2017. Local distrust and regime support: sources and effects of political trust in China. Political Research Quarterly, 70(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912917691360.

Chen, F. 2003. Industrial restructuring and workers’ resistance in China. Modern China, 29(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700402250742.

Chen, X. 2009. The power of “troublemaking” protest tactics and their efficacy in China. Comparative Politics, 41(4). https://doi.org/10.5129/001041509x12911362972557.

Cunningham, E., T. Saich, and J. Turiel. (2020). Understanding CCP resilience: Surveying chinese public opinion through time. Final policy brief.

Duckett, J., and N. Munro. 2022. Authoritarian Regime Legitimacy and Health Care Provision: Survey evidence from Contemporary China. Journal of Health Politics Policy and Law, 47(3). https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-9626894.

Easton, D. 1975. A re-assessment of the Concept of Political Support. British Journal of Political Science, 5(4). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123400008309.

Farid, M., and C. Song. 2020. Public Trust as a driver of state-grassroots NGO collaboration in China. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI 25: 591–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09691-7.

Flatø, H. 2022. Trust is in the air: pollution and chinese citizens’ attitudes towards local, regional and central levels of government. Journal of Chinese Governance, 7(2). https://doi.org/10.1080/23812346.2021.1875675.

Han, Z., K. Lin, and P. Tao. 2019. Perceived Quality of Governance and Trust in Government in Rural China: a comparison between villagers and officials. Social Science Quarterly, 100(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12650.

Hu, A. 2021. Outward specific trust in the balancing of hierarchical government trust: evidence from mainland China. British Journal of Sociology, 72(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12798.

Hu, A., and C. A. Yin. 2022. Typology of political Trustors in Contemporary China: the relevance of Authoritarian Culture and Perceived Institutional performance. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI 27: 77–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-021-09751-6.

Huang, H., C. Intawan, and S. P. Nicholson. 2022. In Government We Trust: Implicit Political Trust and Regime Support in China. Perspectives on Politics, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SJKRGG.

Huang, X. 2020. The Chinese Dream: Hukou, Social mobility, and Trust in Government. Social Science Quarterly, 101(5). https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12847.

Kang, S., and J. Zhu. 2021. Do People trust the Government more? Unpacking the distinct impacts of Anticorruption policies on Political Trust. Political Research Quarterly, 74(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912920912016.

Li, L. 2004. Political trust in rural China. Modern China, 30(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700403261824.

Li, L. 2013. The magnitude and resilience of Trust in the Center: evidence from interviews with Petitioners in Beijing and a local Survey in Rural China. Modern China, 39(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/0097700412450661.

Li, L. 2016. Reassessing Trust in the Central Government: Evidence from Five National Surveys. In China Quarterly (Vol. 225). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741015001629.

Li, L. 2022. Decoding Political Trust in China: a machine learning analysis. China Quarterly, 249. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741021001077.

Li, Z., and X. Wu. 2018. Social Policy and Political Trust: Evidence from the New Rural Pension Scheme in China. In China Quarterly (Vol. 235). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741018000942.

Mitter, R., and E. Johnson. 2021. May). What the West gets wrong about China. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2021/05/what-the-west-gets-wrong-about-china.

Munro, N. 2018. Does refusal bias influence the measurement of chinese political trust? Journal of Contemporary China 27 (111): 457–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2018.1410981.

Ratigan, K., and L. Rabin. 2020. Re-evaluating Political Trust: the impact of Survey Nonresponse in Rural China. In China Quarterly (Vol. 243, 823–838). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741019001231.

Shen, X., and R. Truex. 2021. In Search of self-censorship. British Journal of Political Science, 51(4). https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000735.

Song, E. E. 2022. How Outsourcing Social Services to NGOs bolsters Political Trust in China: evidence from Shanghai. Chin Polit Sci Rev. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41111-021-00207-z.

Su, Z., S. Su, and Q. Zhou. 2021. Government trust in a time of crisis: Survey evidence at the beginning of the pandemic in China. China Review, 21(2).

Su, Z., Y. Ye, J. He, and W. Huang. 2016. Constructed hierarchical government trust in china: formation mechanism and political effects. Pacific Affairs, 89(4). https://doi.org/10.5509/2016894771.

Tong, Y., and S. Lei. 2010. Large-scale mass incidents and government responses in China. International Journal of China Studies, 1(2).

Wang, J., and Y. Mou. 2021. The paradigm shift in the disciplining of Village Cadres in China: from Mao to Xi. China Quarterly, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305741021000953.

Wei, Y., Z. Ye, M. Cui, and X. Wei. 2021. COVID-19 prevention and control in China: grid governance. Journal of Public Health (Oxford England), 43(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdaa175.

Wu, C., and R. Wilkes. 2018. Local–national political trust patterns: why China is an exception. International Political Science Review 39 (4): 436–454. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192512116677587.

Wu, C., Z. Shi, R. Wilkes, J. Wu, Z. Gong, N. He, Z. Xiao, X. Zhang, W. Lai, D. Zhou, F. Zhao, X. Yin, P. Xiong, H. Zhou, Q. Chu, L. Cao, R. Tian, Y. Tan, L. Yang, … Nicola Giordano, G. 2021. Chinese Citizen satisfaction with Government performance during COVID-19. Journal of Contemporary China, 30(132). https://doi.org/10.1080/10670564.2021.1893558.

Zhang, X., W. Luo, and J. Zhu. 2021. Top-down and Bottom-Up lockdown: evidence from COVID-19 Prevention and Control in China. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-020-09711-6.

Zhao, X., and Y. Xie. 2022. The effect of land expropriation on local political trust in China. Land Use Policy, 114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2021.105966.

Zuo, C., Z. Wang, and Q. Zeng. 2021. From poverty to trust: political implications of the anti-poverty campaign in China. International Political Science Review. https://doi.org/10.1177/01925121211001759.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Xi, J., Ratigan, K. Treading Through COVID-19: Can Village Leader-Villager Relations Reinforce Public Trust Toward the Chinese Central Government?. J OF CHIN POLIT SCI 29, 31–53 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-023-09846-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11366-023-09846-2